THEORETICAL ESSAY

LOPES, Pablo de Oliveira [1], NEVES, Paulo Sérgio da Costa [2], PEREIRA, Lucas de Almeida [3]

LOPES, Pablo de Oliveira. NEVES, Paulo Sérgio da Costa. PEREIRA, Lucas de Almeida. An interdisciplinary view of AIDS in the 1980s: On stage, Journalism and Health. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 05, Ed. 08, Vol. 09, pp. 46-69. August 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/health/eyesight-interdisciplinary, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/health/eyesight-interdisciplinary

SUMMARY

This article presents acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS, in Portuguese, or AIDS), when it appeared in the 1980s from an interdisciplinary perspective: on the one hand, signs, symptoms, diagnostic methods and treatment are addressed and are part of the biomedical model that participates in the interpretation of this disease; on the other, the representations of the disease in journalistic articles published in the newspaper O Globo, one of the most important in Brazil. Health and Journalism help to build ideas and understand concepts, prejudices and stigmas that relapse dwell and still fall on the disease that became known as the gay plague, one of several denominations attributed to AIDS when it arose. It is discussed whether it is possible to understand the health-disease process from a plural perspective, which goes beyond the limits of medicine. For this, we analyze texts from the newspaper O Globo, which deal with the HIV/AIDS binomial, paying special attention to the language and lexicography used in the elaboration of them, and taking into account the medical view about the disease in the 1980s. The work allows us to conclude that it is possible and necessary to face the health-disease process using not only biological phenomena, but using social, economic, political and environmental aspects, in front of various disciplinary fields.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, scientific dissemination, scientific journalism, interdisciplinarity.

INTRODUCTION

AIDS is the acronym used for Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, a disease characterized by severe immune system dysfunction of individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). According to the Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines for The Management of HIV Infection in Adults (2018), its evolution can be divided into three phases: Acute infection (Acute Retroviral Syndrome – SARS), which may arise a few weeks after the initial infection, with manifestations such as fever, chills, sweating, myalgia, headache, sore throat, gastrointestinal symptoms, generalized lymphadenopathies and rashes. Most individuals have self-limited symptoms, which disappear after a few weeks. However, most are not diagnosed due to the similarity with other viral diseases; Asymptomatic infection, of variable duration, which may reach a few years, and symptomatic disease, of which AIDS is its most severe manifestation, which occurs to the extent that the patient has more marked alterations in immunity, and opportunistic infections and neoplasms appear.

According to the Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines for The Management of HIV Infection in Adults (2018), opportunistic infections such as atypical or disseminated pulmonary tuberculosis, Pneumocistis jiroveci pneumonia, cerebral toxoplasmosis, oro-esophageal candidiasis, cryptococcal meningitis and cytomegalovirus retinitis arise at this stage. Rare tumors in immunocompetent individuals, such as Kaposi’s sarcoma and certain types of lymphoma, may also occur. The etiological agent is an RNA virus, retrovirus, currently called Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), with 2 known types: HIV-1 and HIV-2. Before 1986, it was called HTLV-III/LAV.

The disease can be transmitted sexually, blood (parenteral) and from mother to child, in the course of pregnancy, during or after childbirth, and by breastfeeding in the postpartum period. Risk factors associated with HIV transmission mechanisms are: frequent variations of sexual partners without condom use, presence of other sexually transmitted diseases, use of blood or its derivatives without quality control, sharing or use of unsterilized syringes and needles (as is the case among injecting drug users), pregnancy in an HIV-infected woman, and organ transplantation or semen reception from infected donors. It is important to note that HIV is not transmitted by social or family life, hug or kiss, food, water, mosquito bites or other insects. Such information is important, even today, because it acts to reduce ignorance and prejudice about people living with HIV/AIDS.

After explaining the biomedical part that involves the theme of this text, it is worth mentioning that for the discussion of information published on AIDS in the 1980s, the newspaper O Globo was chosen, due to the influence it exerts on the discourse of the Brazilian press. Globo is among the vehicles with the largest circulation in the country and therefore occupies an important position in the dissemination of news and in the possible reproduction of stereotypes and dissemination of prejudices. Despite being published in Rio de Janeiro, the penetration in other Brazilian states transports the rhetoric of its journalists to various regions of the national territory.

Using the search tools of the newspaper O Globo website and using the keywords ‘AIDS’, ‘gay’, ‘homosexuals’, ‘prejudice’ and ‘discrimination’ we randomly selected journalistic texts from the 1980s and early 1990s, aimed at homosexuals and HIV-AIDS, and analyzed them based on the semantics of the words. We verified the presence of stereotypes or facts that characterize the formation of prejudices in relation to people living with HIV and AIDS.

It is possible to develop a study based on the chronological inventory of the words, seeking their meanings according to the values imposed by the discriminatory discourse of those who use them. The study of the lexicon may indicate the mentality of a given epoch. Thus, the reflection on the texts published in the printed newspaper will fall on the semantics of the words. Words assume distinct connotations depending on the context in which they are employed and the ideology of those who use them. Ideas, concepts, behaviors, attitudes and public policies are influenced by discourses, whose structures depend on the words used and what they mean. This applies to the dissemination of prejudices and stereotypes about certain population groups, such as homosexuals. Based on this premise, we analyzed the journalistic texts of the 1980s, considering the approach given to AIDS and homosexuals, in that historical period, from the deconstruction of discourses, as systematized by Tucci Carneiro (1994).

MEDICINE AND JOURNALISM: REPRESENTATIONS OF AIDS IN HOSPITALS AND NEWSSTANDS

The first report of O Globo that we highlight pointed out in the title the lack of knowledge of the doctors themselves about the disease: “Heusi will not punish coroners who refuse to necropsy the aids.” (O GLOBO, 1987, p. 9). The matter informs that the coroners of the Legal Medical Institute (IML) who refused to perform the necropsy of the body of the prisoner Luciano Alves Azeredo, who died of AIDS, would not be punished. The statement was made by Marcos Heusi, Secretary of Civil Police at the time, and unveils how the speech of the authorities treated the disease and its victims. The advance of science towards the understanding of the disease allowed doubts to be clarified and, in the sissy, situations like this not to be repeated. The lack of knowledge and mastery of the disease made potential health professionals disseminators of stereotypes and stigmas. Physicians and nurses could play an ambiguous and even contradictory role from the social and ethical point of view: caring, supporting, but also being able to discriminate.

Contributing even more to a reflection, the text of the same matter, of June 24, 1987, adds some comments and questions, stating that it is understandable the fear of contagion of the doctors of the IML, but demonstrating non-conformity with the fact that the doctors, at that time, still do not know the size of the danger of contagion during a necropsy. The report also casts doubt on the authenticity of the death certificates given and the confidence that could be placed in the statistics about the syndrome. Finally, there is an inquiry that calls into question Brazil’s public policies at the time: “is there in fact in Brazil an official anti-AIDS plan that really covers all aspects of the problem?”. (O GLOBO, 1987, p. 9).

The question was pertinence for the period, since it was a phase in which little was known about the disease. Everything was new, surrounded by doubt. Incipient public policies did not transmit security to the population. According to Marques (2002), the period between 1987 and 1989 was the period in which the National AIDS Program actually developed. The national coordination centralized the actions and moved away from state programs and NGOs. These, for their part, have gained space and prominence over the years and have played a significant role in the discussion of the National Program.

The official response at the national level, in the face of the AIDS epidemic, finally began to be built, almost two years after the Minister of Health recognized it as an emerging public health problem in the country (May 1985). (MARQUES, 2002, p. 53).

Returning to the description of the disease, we highlight the incubation period, the one between HIV infection and the acute phase or the appearance of circulating antibodies. According to the Ministry of Health, through the Cadernos de Primary Care Series (2002), for the vast majority of patients, this period varies between 1 and 3 months, after infectious contact, and may occasionally reach 6-12 months in a few cases reported in the medical-scientific literature. According to the Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines for The Management of HIV Infection in Adults (2018), latency period is that between HIV infection and the symptoms and signs that characterize hiv disease (AIDS). It is estimated that the average time is ten years. The period of transmissibility is variable, but the HIV-infected individual can transmit the virus during all phases of the infection, and this risk is proportional to the magnitude of viremia and the presence of other co-factors.

On diagnosis, laboratory detection of HIV is performed through techniques that research or quantify antibodies, antigens, genetic material by molecular biology techniques (viral load) or direct isolation of the virus (culture). In practice, tests that research antibodies (serological) are the most used. The appearance of antibodies detectable by serological tests occurs within an average period of 6 to 12 weeks of initial infection. The ‘immunological window’ is called this interval between infection and the detection of antibodies by conventional laboratory techniques. During this period, serological tests may be false-negative. Due to the importance of laboratory diagnosis, particularly due to the consequences of ‘labeling’ an individual as HIV positive and to have greater safety in the control of quality of blood and derivatives, according to the Cadernos de Atenção Básica Series (2002), it is recommended that laboratory detection tests eventually reagents in a first sample be repeated and confirmed according to the standardization established by the Ministry of Health[4].

There is no cure for AIDS; but in recent years, great advances have been made in the knowledge of the pathogenesis of HIV infection; several antiretroviral drugs have been developed and have been shown to be effective in partially controlling viral replication, decreasing disease progression and leading to a reduction in the incidence of opportunistic complications. There was an increase in survival, as well as a significant improvement in the quality of life of individuals. According to data from the Cadernos de Saúde Series of Primary Care (2002), in 1994, it was proven that the use of Zidovudine (AZT) by the pregnant woman infected during pregnancy, as well as by the newborn, during the first weeks of life, can lead to a reduction of up to 2/3 in the risk of transmission of HIV from mother to child.

Since 1995, the use of monotherapy has been abandoned, and it is recommended by the Ministry of Health to use combined therapy with two or more antiretroviral drugs to control chronic HIV infection. Currently, the recommended standard antir[5]etroviral therapy is three or more drugs, and the use of double therapy is an exceptional situation (certain chemoprophylaxis for occupational exposure). There are numerous possibilities of therapeutic regimens indicated by the National Coordination of STD and AIDS. “No less important is to emphasize that Brazil is one of the few countries that fully finances the care of aids patients in the public health network.” (BRASIL, 2002, p.13).

According to the Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines for The Management of HIV Infection in Adults (2018), the onset of ART should be encouraged for all people living with HIV, regardless of the LT-CD4+ count. In the Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines for The Management of HIV Infection in Adults 2013, a prospective study was found in an African cohort of 3,381 serodiscordant heterosexual couples, in which 349 individuals started treatment during the follow-up period. Only one case of transmission occurred in the partnerships of the participants who were in treatment and 102 in the partnerships in which the HIV-infected person was not in treatment. This represents a 92% reduction in the risk of transmission.

Also according to the Clinical Protocol (2013), more recently, the results of the HPTN052 study, the first randomized clinical trial, which evaluated the sexual transmission of HIV among serodiscordant couples, became public. A total of 1,763 couples with LT-CD4+ count between 350 and 550 cells/mm3 were randomized for immediate initiation of treatment or to start it, when the LT-CD4+ count was below 250 cells/mm3. During the study, there were 39 episodes of transmission, of which 28 were virologically linked to the infected partner; only one episode occurred in the early therapy group, with a 96% decrease in transmission rate when the person living with HIV started treatment with LT-CD4+ count between 350 and 550 cells/mm3.

According to the Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines for The Management of HIV Infection in Adults (2018), ART can be initiated provided that the person living with HIV is properly informed of the benefits and risks related to it, besides being strongly motivated and prepared for treatment, respecting the autonomy of the individual. Emphasis should be given to the fact that therapy should not be discontinued.

In line with protocol 2018, initial therapy should always include combinations of three antiretrovirals, being two nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI)/nucleotide analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors (ITRNt), associated with a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) or protease inhibitor with ritonavir reinforcement (IP/r) or integrase inhibitor (INI). As a rule, the first-line scheme should be as follows: Tenofovir (TDF), Lamivudine (3TC) and Dolutegravir (DTG), an INI.

Another important aspect of treatment is a dynamic and multifactorial process that encompasses physical, psychological, social, cultural and behavioral aspects and involves shared decisions between the person living with HIV, the health team and the social network. Medication adhering to a drug involves taking it at the prescribed dose and frequency. On the other hand, in addition to the correct use of medications, treatment adhering to treatment, fully understood, also involves the performance of tests and consultations as requested. Poor adherence is one of the main causes of therapeutic failure. A direct relationship has not been established between adherence levels and efficacy of the different antiretrovirals, however “most studies indicate that it is necessary to take at least 80% of doses in order to obtain adequate therapeutic response.” (Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines for The Management of HIV Infection in Adults, 2013, p.53).

It is very important that the patient knows the characteristics of the disease and clearly understands the objective of antiretroviral therapy to participate in the decision to start it, understanding the relevance of continued and correct use of the drug, in order to achieve an adequate suppression of virological replication. Therefore, it is essential that the patient has basic knowledge about the disease, the forms of transmission, the meaning and usefulness of laboratory tests (such as T-CD4 lymphocyte count and viral load) and possible short- and long-term adverse effects related to therapy. Having access to information, the patient is strengthened to face the adversities brought by the disease and its treatment. The patient’s medical and psychosocial evaluation allows identifying the ways of coping, the difficulties of acceptance and living with the positive diagnosis for HIV. The health team should take these aspects into account when preparing the therapeutic plan. “Self-care is also related to living long and well, and lack thereof also results in illness and death.” (GOMES; SILVA, U.S.; OLIVEIRA, 2011, p.6).

The prevention of sexual transmission is based on information and education, and combined prophylaxis is the greatest asset in combating the disease.

In turn, the prevention of blood transmission has as guidelines: a) blood transfusion: all blood to be transfused must be tested for detection of anti-HIV antibodies. The exclusion of donors at risk increases transfusion safety, mainly because of the ‘immune window’; b) blood products: blood products, which can transmit HIV, must undergo a process of treatment that inative the virus; c) injections and sharp-cutting instruments: when not disposable, they must be thoroughly cleaned and then disinfected and sterilized. Disposable materials, after use, must be packed in appropriate boxes, with hard walls, so that accidents are avoided. HIV is very sensitive to standardized methods of sterilization and disinfection (of high efficacy). The virus is inactivated through specific chemicals and heat, but is not inactivated by irradiation or gamma rays; d) donation of semen and organs: rigorous screening of donors; f) perinatal transmission: use of Zidovudine in the course of pregnancy of HIV-infected women, according to a scheme standardized by the Ministry of Health, associated with cesarean delivery, offers a lower risk of perinatal transmission of the virus. However, the prevention of infection in women is still the best approach to avoid transmission from mother to child.

The issue of HIV blood transmission is highlighted in a story in O Globo, on February 15, 1987, which pointed out: “Risk of AIDS in transfusion terrifies patients.” (BERTOLA, 1987, p. 21). The text of the journal addresses the fear of patients, especially hemophiliacs, who saw in transfusions one of the overwhelming forms of expansion of the disease in the country, which did not have adequate control of the transfused blood. Plausible and necessary weighting, which should accompany other aspects, such as information that other diseases can also be transmitted via blood transfusion. At the time, the fear of contracting HIV was so great that it was possible to forget that hepatitis B and C, for example, can be contracted during such a medical procedure. This is what the same story indicates: “AIDS is just one of many diseases caused by a poortransfusion.” (BERTOLA, 1987, p.21).

In view of all the difficulties inherent in the diagnosis of HIV infection, one more is imposed: according to the Ministry of Health, based on the Clinical Protocol and Therapeutic Guidelines for The Management of HIV Infection in Adults (2013), the risk of suicide in infected patients is three times higher than in the general population. A review study showed that 26.9% of people living with HIV reported suicidal ideation, and 6.5% attribute this ideation to side effects of antiretrovirals; 22.2% had a suicide plan; 23.1% claimed to have intended to kill themselves; 14.4% reported a desire to die and 19.7% committed suicide (11.7% of them with AIDS and 15.3% in other stages of the disease).

It is worth noting that, although some patients report suicidal ideation as a side effect of antiretroviraldrugs, a study conducted in Switzerland showed that patients undergoing antiretroviral treatment are less at risk of committing suicide than those who do not use medications. The use of antiretrovirals prolongs the lives of people living with HIV, giving them more quality.

The panorama presented shows the reality of people living with HIV and the health professionals who care for such patients. A disease with multiple clinical manifestations, medications with various side effects and various aspects to be considered in the choice of treatment, AIDS requires a holistic view of the patient, which should be seen as a single individual, with physical, behavioral and emotional characteristics that differ from others. The complexity of the disease makes it a vast and fertile field for the construction of social representations. For Gomes; Silva e Oliveira (2011), the reflection on the spread of AIDS requires considering the transformations of this epidemic in its historical context, especially in relation to the forms of transmission, the tendencies of vulnerability to the disease and the meanings constructed to face this reality.

Clinical manifestations such as weight loss and diarrhea weaken the patient and make him more fragile, vulnerable and subject to physical and psychological complications. Such clinical manifestations can limit social interaction in a significant way, with important physical and psychological repercussions, serving as a trigger for stigma and the construction of representations in the collective imaginary. Homosexuality and weight loss are, for example, two variables that can lead to a stereotype. Many gays have been labeled as aids carriers simply because they are thin. Thinness does not necessarily come from the disease, but the stereotyped image of the promiscuous homosexual, who does not preserve his own health, has already yielded such a sentence to many. Medicine has officially contributed, even involuntarily, to the spread of prejudice and discrimination. On this association between disease and AIDS, Lucinha Araújo stated, in an interview with the newspaper O Globo, that:

currently, no artist can get sick, because it is soon speculated that he has AIDS. How do you see this stigma? It’s the price of fame. Public people are very exposed. You struggle to be known and the day you are known loses privacy. Today, any artist who slims down has Aids. (LUCAS, 1990, p.7).

More than the price of fame, it’s the price of stereotype. Not only did the artists go through this. Unknown, anonymous, people who did not occupy a prominent place in the media were also the subject of such speculation. Skinny and sick. Segregated and labeled by their physical appearance.

For Gomes; Silva and Oliveira (2011) there are several factors that require adequate use of antiretrovirals, which often lead to treatment abandonment. One of the reasons that provoke such an attitude is related to the side effects of these drugs, especially the alteration of body image that can characterize HIV-positive people as ‘aids’ due to lipodystrophy.

According to Seidl and Machado (2008), the use of the term lipodystrophy related to Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome began in the late 1990s and referred to the loss of subcutaneous fat in the face and upper and lower limbs of people with HIV undergoing antiretroviral treatment with protease inhibitors. Also according to Seidl and Machado (2008), scholars have found that lipodystrophy can cause psychological and emotional difficulties relevant to affected people. “HIV-associated lipodystrophy affects 40 to 50 percent of patients infected with the virus.” (DIEHL, 2008, p.658).

The term ‘aids’, so loaded with symbology, is still present in the vocabulary, thoughts and discursive constructions of some individuals. Negative word used in newspaper reports in the 1980s, such as that published by O Globo on May 29, 1988, by Fanny Zygland. The word was not included in the title: “Families reject patients with AIDS”, but it was already mentioned in the first paragraph: “As aids cases multiply across the country, rejection by aids is also expanded.” (1988, p.10). The text of O Globo also adds that the problem became more serious, when it was found that, five years after the emergence of the first cases of the disease, Brazil did not have any reception policy for patients rejected by their families.

Rejection to the sick appeared in the verb used – ‘reject’-, which means to repel, refuse, and also in the term ‘aigotic’. At that time, the expression was not considered politically incorrect and still occupied a large space in the preference of journalists of the most diverse newsrooms.

THE ROLE OF THE PHYSICIAN IN THE PERPETUATION OF PREJUDICE

On June 12, 1987, a report by Eliane Lobato, emblazoned on the Second Notebook of O Globo, bears the title “Not everything is drama” and part of the text carries the meaning of the disease at the time: “But AIDS, on the contrary, means death, therefore, end of days, dark nights.” In addition to these representations, the article adds: “Four years ago, AIDS was synonymous with gay plague.” (1987, p.5). The term ‘gay plague’ crosses social discourses and representations, even though the matter passes the message of disappearance of the association between gays and AIDS.

At that time, when AIDS was synonymous with gay plague, the play had a justifiable didactic sense. Today “Why me?”, the same piece by Hoffman, which was translated by Luis Fernando Veríssimo and Luiz Fernando Tofanelli and which Roberto Vignati directs at the Teatro da Praia, is released. The moment is quite another: AIDS is no longer restricted to homosexuals and has become a fear in the lives of all people. (LOBATO, 1987, p.5).

As mentioned earlier, in June 1981, the U.S. Center for Disease Control recorded the first cases of the disease considered unknown at the time. In 1982, she was given the provisional name ‘5 H Disease’, due to cases identified in homosexuals, hemophiliacs, Haitians, heroinaddicts – injectable heroin users – and prostitutes – hookers – in English. Provisional denomination, also fraught with stigma and prejudice. Illustrating this context, another article from O Globo appears, entitled “AIDS: between stigma and panic, the incidence of which is: “Discrimination and panic. These are the two predominant trends in the population when talking about AIDS.” He added: “Due to lack of information, most people believe that a simple handshake transmits the disease. Others think that only homosexual practice spreads the virus.” (1985, p. 20).

The article, which dedicates part of the text to highlight the concern of the authorities to end the stigma of AIDS, highlights: “Gay cancer has increased discrimination as old as man’s history. Discrimination against homosexuals has existed, but it has increased greatly since AIDS emerged, stigmatized as gay cancer.” (O GLOBO, 1985, p.20).

In tow the problem addressed in the Globe, it is worth pointing out that stigma and social prejudice are attitudes generated, to a large extent, by the fear of contagion and lack of information, which cause discomfort and suffering in people living with HIV, targets of social neglect. Themes that reflect this social representation are the distancing of people, friends, rejection of physical contact (handshake, kiss on the face).

As a way to prevent medicine from contributing to the perpetuation of pejorative marks and attribute to people or population groups characteristics that may offend them, causing psychological and emotional problems, it is relevant to highlight an aspect related to medical care: humanization. “With all the advantages of globalization, we see, at the same time, saddened, the distance between people. It is increasingly common to see doctors and patients giving way to numbers, exams.” (LOPES, 2017, p. 1).

According to Gallian (2001), the process of dehumanization is a consequence of the separation between medicine and the humanities, which took place from the end of the 19th century. Understanding historical development, replacing the humanistic sciences in the context of formation is essential for the (re)humanization of Medicine. Still according to the author, Western medicine was an essentially humanistic science. Based on the philosophy of nature and with a theoretical system focused on a holistic view, it understood man as a being endowed with body and spirit. Diseases were not only considered a special problem, but as part of a larger reality, because as he states, “the causes of diseases, therefore, should be sought not only in the organ or even in the sick organism, but also and especially in what is essentially human in man: the soul.” (GALLIAN, 2001, p. 1).

The classical doctor was therefore a philosopher; someone who understood the laws of nature and the human soul. The doctor should be, fundamentally, a humanist. A professional who took into account biological, environmental, cultural, sociological, family, psychological and spiritual aspects to diagnose and start the treatment of a disease. Today’s physician, a scientist, a technician, does not view the patient with such a vision: deep, broad and humanistic. Of course, there are exceptions, but they are increasingly rare, since medical training, the undergraduate course, does not highlight multidisciplinary teaching.

Despite the rapid development of the so-called experimental method (scientific method) during the 19th century, the humanistic view of medicine continued to preponderat and contribute to medical education. The doctor was a profound connoisseur of the content, but also a lover of literature, philosophy and history. “A cultured man, the romantic physician allied his scientific knowledge with the humanistic and used both in the formulation of his diagnoses and prognoses.” (GALLIAN, 2001, p. 2). The doctor maintained close proximity to his patients and their families. The authentic family doctor knew that healing was not merely technical, but involved psychological, social, cultural, and religious issues.

However, even in the 19th century, which consecrated medicine as an activity marked by humanization, important discoveries were found in fields such as microbiology to start a revolution in the field of pathology, generating profound transformations in medical science. The development of laboratory analyses and other clinical methods transformed diagnostic methods and penicillin appeared as a major star in the treatment of infections. “There was a real miracle, and as the 20th century began, everything was beginning to imply that medicine was about to reach its golden age, its stage of ‘exact science’.” (GALLIAN, 2001, p. 2-3).

The advances achieved in the technological field transformed the training and performance of the physician, who began to value principles different from those existing in the nineteenth century. “History, literature and philosophy were not but important sciences, but for the physician they could add little now that the new discoveries and effectively scientific methods opened new dimensions.” (GALLIAN, 2001, p. 3). The valorization and thorough and systematic study of the physical-chemical behavior of organs, tissues and cells gained space. Medicine ceased to rely on the human sciences to sustain itself, primarily, in the exact and biological sciences.

For Gallian (2001), the process of overvaluing technological means, which accompanied the development of medicine in recent decades, led to the ‘dehumanization of the doctor’. The professional became increasingly a technician, a specialist, deep connoisseur of complex exams; but sometimes ignorant about the human aspects of the patient. And this happens or happened not only because of the requirement of increasingly specialized training, but also because of changes in working conditions, which tended to proletize the doctor, limiting his time to be with the patient, giving him attention.

To assist many patients, to deal with endless queues of people, not to succumb to the lack of medicines or other supplies necessary for good medical practice: this is part of the daily lives of many professionals. From this perspective, it may be possible to understand one of the reasons why the doctor abandoned humanization. The improvement of the Unified Health System involves not only the greater availability of financial resources and the investment in technical training, but also the humanization of care.

THE PERFORMANCE OF THE PRESS IN THE CONSTRUCTION OF MEANINGS

It can be said that ignorance about the disease contributes to the reproduction of stereotypes. The press sometimes plays a central role in this story, but it can also play another role: to clarify.

According to Darde (2006), the Brazilian press played a fundamental role in the construction of meanings about AIDS in the early 1980s. In the United States, the first cases of the disease were diagnosed in male homosexuals, which led doctors, supported by the media, to think about the emergence of a gay cancer. Temporary name chosen at the time, since the causative agent of the disease was not known. Even almost 20 years after the discovery of the disease, prejudice was still spreading. The dubious press, which acted by disseminating stereotypes, also fulfilled another function: denouncing prejudice. It’s the construction of senses. Follow text from O Globo:

Victims of the virus of prejudice. Volunteers in AIDS vaccine testing suffer discrimination even from relatives and friends. In the last three years, the life of Paulo César Leonardo, a 46-year-old medical radiology technician, has turned upside down. The first blow – the death of the woman, on July 6, 1994, victim of AIDS – followed three bites on the arm that brought to Paul Caesar the virus of distrust and prejudice. A volunteer for the first hiv vaccine testing program in Brazil, he met the contempt of his co-workers and was deprived of contact with his wife’s first marriage – the 9-year-old boy’s maternal grandparents, who have custody of the boy, even banned phone conversations. Confused by many as a patient of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, Paulo César has been feeling in his own skin the stigma and discrimination that surround HIV carriers. (GIANOTTI, 1997, p.16).

Most of the first reports in the Brazilian media had as main reference the North American news agencies, which greatly influenced the way the disease reached the Brazilian imagination. The vast majority of the first AIDS patients in Brazil, the United States and Europe were male homosexuals and the stigma of promiscuity fell on them. “Prejudice and intolerance were present in conservative discourses, in which the term aids is constructed, a single category, indivisible and, mainly, separated from society.” (DARDE, 2006, p.19). At the time, the term ‘aids’ was not only used but also meant an enemy condemned to physical death, useless for social development. “Precisely the stigmatization of infected people and groups, stimulated by the construction of meanings of the disease in the media, played a fundamental role for the spread of HIV/AIDS in society.” (DARDE, 2006, p.19).

The Globe showed in the title of a report of April 9, 1989, in the notebook Rio, the stigma and barriers faced by HIV patients at that time: “Aids and the long wait for a bed.” (COHEN, 1989, p. 20). It waits for beds reserved specifically for patients with the disease. Perhaps this was the solution found by some health professionals and authorities, who isolated HIV carriers. Isolation that was physical and social at the same time.

The term ‘aideetic’, loaded with negative weight, prejudiced, exclusionary and discriminatory, was added to the segregation imposed by the reservation of specific beds in hospitals. According to the article in O Globo of April 9, 1989, an Aided Care Center, created by the Health Department of the State of Rio de Janeiro, which regulated hospital beds for HIV-infected patients. Patients with other diseases did not mix with aids. “Through the phone 590-5252, the Aided Care Center, created by the State Health Department, operates.” (COHEN, 1989, p. 20).

Patients waited a long time for a bed and the chance of getting a place in a hospital was conditional on the death of a patient already hospitalized.

Wasn’t there a possibility of improvement and discharge home? Aids and death were confused. They were synonymous. As seen in the dialogue between the reporter of O Globo and the attendant of the Health Department:

Hello. Please, I need to urgently hospitalize an AIDS patient. What hospital are there vacancies in at the moment? Not at all. Leave the patient’s name and data and we’ll schedule it and we’ll call you back when you wander a bed. But what are the prospects? It varies a lot. Today there are four patients at the front. We have to wait for someone to die to get a job. (COHEN, 1989, p. 20).

In the turbulent context, it was reported that, in private medicine, health plans stopped paying the expenses of HIV patients: “When aids diagnosis is made, group medicine companies stop insurance on patient expenses, despite being required by resolution of the Regional Council of Medicine to attend to all diseases.” (COHEN, 1989, p.20).

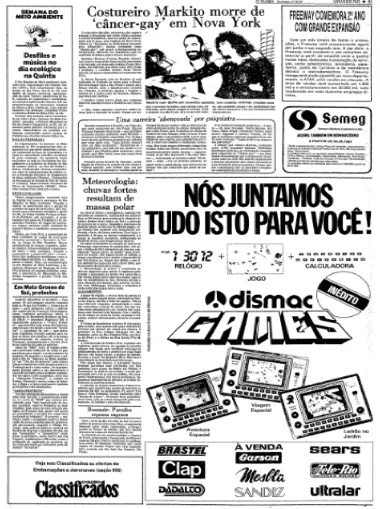

According to Darde (2006), the first Brazilian case of AIDS was officially reported in 1982, but the disease became ‘national’ after the death of seamstress Marcos Vinícius Resende Gonçalves, the Markito, 31 years old. The fact that the first Brazilian cases were also with male homosexuals reinforced the image of the AIDS patient brought by the American press. On June 5, 1983, Globo published a story about Markito’s death: “Seamstress Markito dies of ‘gay cancer’ in New York.” The Globe reported that the creator of sensual and stripped couture, who dressed several Brazilian singers and actresses, had died in New York, victim of ‘Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome’, a disease then known as ‘gay cancer’ for attacking mainly homosexuals. The association between homosexuality and the disease in question is clear.

Figure (O Globo Collection) – Seamstress Markito dies of ‘cancer-gay’ in New York.

On the other hand, the dissemination of aids news by the Brazilian media allowed society to demand a more energetic and efficient action of national authorities. Non-governmental organizations emerged and the homosexual movement gained projection in articles published by the press. According to Darde (2006), at the beginning of the epidemic in Brazil, journalistic coverage was based on material produced by international sources and agencies, sometimes replicating content marked by misinformation and prejudice. Also according to the author, the search for aids identity showed, mainly, the suffering of celebrities, such as singer-songwriter Cazuza.

People with HIV were treated as objects, being relieved of the discussion about the various aspects of the epidemic. For Darde, since the birth of the first non-governmental organizations in 1985, people living with HIV began to have their own voice, as opposed to the official voice of the State. An issue that is fundamental in the studies of Journalism: the voice of the oppressed, in this case the AIDS patients, was always in the background, while the official speech – of the State and Science – predominated in the journalistic discourse.

The Globe’s article, published on October 28, 1990, can be used for a reflection on what Darde proposes and that was reported in the previous paragraphs. In this report, Lucinha Araújo, mother of singer Cazuza, gives an interview and talks about prejudice and misinformation. The title of the report is: ‘Awareness and respect’. The Globe treats AIDS as something serious and gives voice to a woman from rio de Janeiro’s elite, mother of a successful artist. Lucinha Araújo charges the authorities for attitudes or actions against the disease. This is clear when the interviewee answers the following question from journalist Vera Lucas: “How do you, who have been in large international AIDS treatment centers, analyze the situation of our hospitals?”. Cazuza’s mother responds:

it’s chaotic. Hospitals don’t have the money to buy drugs, expand the number of beds, pay specialized professionals, nothing. I don’t know if this is happening out of the authorities’ case, but I’m sure the problem is the responsibility of the Federal Government. But we can’t just wait and wait for the government to sort it all out. It’s about time private companies helped. (LUCAS, 1990, p. 7).

Lucinha Araújo acts as interlocutor of the less favored, demonstrates knowledge on the subject, treats it seriously, but does not hear the discourse of the vulnerable, the invalidated. In the following excerpt, it turns out how Lucinha is announced: the mother of anonymous aids. “After spending three years caring for Cazuza, Lucinha, fulfilling her son’s promise, became the mother of anonymous poor aidists hospitalized in precarious and unequipped Brazilian hospitals.” (LUCAS, 1990, p.7).

The press vehicle recognizes the existence of such individuals, who are not heard, but does not give space to them. Choose a spokesperson, someone you know, prominent in society at the time, to speak on their behalf.

It can be believed that as long as a person with a particular stigma achieves a high financial, political or occupational position – depending on their importance of the stigmatized group in question – it is possible that a new career will be entrusted to them: to represent their category. (GOFFMAN, 1963, p. 36).

Cazuza’s mother does not have AIDS and therefore does not carry the stigma. However, after the death of her son, who contracted disease, she began to stand out as a representative of people living with HIV, that is, the consumer elite of the newspaper is represented and frightened, because she was witnessing the advance of the disease that they considered to be restricted to the LGBT world.

The part of the matter that was highlighted above carries the stigma of poverty and frailty, which accompanies patients in the face of the disease. This is the highlighted side: sick and subjugated, patients are in a bad situation, because they are in poor quality hospital institutions. Reality of the sick, who faced obstacles that sometimes seemed insurmountable. But were there only HIV carriers among the poor? Didn’t the rich get sick? Occupying beds in private hospitals and with more resources, did rich patients have another scenario in front of them? Because they had possessions, they were faced with less prejudice? Why not give voice to the oppressed?

According to SPINK (2001), on October 30, 1985, the French newspaper Le Figaro published: “AIDS is the first disease of the media” phrase that highlighted one of the most striking aspects of the epidemic – its widespread dissemination in the world by mass communication vehicles – and the construction of a new social phenomenon: AIDS-news. AIDS has become a social phenomenon marked by modern technologies in the field of medical research, social activism and the impressive media dimension it has assumed. Dimension expressed in numbers, as Spink claims: “From September 1987 to December 1996, Folha de São Paulo published 7,074 articles that, in some way, referred to AIDS; that is, over nine years, an average of two subjects per day has been published.” (2001, p. 852).

Also according to Spink (2001), the media fulfills two functions: on the one hand, the press announced the appearance of a new phenomenon in the field of pathology; and, on the other hand, it defined its contours and allowed the passage of information about the disease from the medical-scientific domain to the social record.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The media influence customs, dictate the agendas of dialogues between citizens and are present in the rhetoric of social actors: in contemporary times, the media has assumed a fundamental role in the processes of meaning production, introducing significant transformations in daily discursive practices.

The media is a showcase, which exposes information, but not in an unpretentious and random way. Influenced by diverse ideologies and interests, it is a powerful device that creates spaces for interaction. Such spaces, without spatial and time boundaries, allow us to reflect on the ethical dimensions of information and communication processes.

A communication vehicle can disseminate news on the most varied subjects, moving through science, health, disseminating (pre)concepts, ideas, images and stimulating debate. But who is responsible for selecting what should or should not be published? There are researchers who believe that when it comes to defining the concept of news by the reader’s interest, journalists find themselves lost.

All the mobilization around what to publish, how it should be published and how a news story should be written generates debates. The choice of the vocabulary of the subjects confronts the struggle for the prevention and treatment of people with HIV and the thinking of society or part of it. Words have many meanings and can represent or symbolize a lot. There are clear examples of change in the language of the texts dealing with AIDS: prostitutes – now called sex workers; patient/victim of AIDS in place of aids – today, person with AIDS; addict or junkie being replaced by drug user. As a result of the changes in the historical context, the aggressive and sensationalist character of the press was giving more space to the politically correct bias.

REFERENCES

AIDS: entre estigma e pânico cresce a incidência. O Globo, Rio de Janeiro, 30 jun. 1985. Caderno Grande Rio, p. 20.

Disponível em: http://acervo.oglobo.globo.com/busca/?tipoConteudo=pagina&or- denacaoData=relevancia&allwords=aids+e+estigma&anyword=&noword=&exact- word=&decadaSelecionada=1980&anoSelecionado=1985. Acesso em: 05 maio 2018.

BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Dermatologia na Atenção Básica de Saúde. Série Cadernos de Atenção Básica. Brasília, 2002, 142 p. Disponível em:<http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/guiafinal9.pdf.> Acesso em: 17 abr. 2020.

BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Protocolo Clínico e Diretrizes para manejo da in- fecção pelo HIV. Brasília, 2013, 416 p. Disponível em: http://www.aids.gov.br/pt- br/pub/2013/protocolo-clinico-e-diretrizes-terapeuticas-para-manejo-da-infeccao-pelo-hiv- em-adultos. Acesso em: 16 abr. 2020.

BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Protocolo Clínico e Diretrizes para manejo da in- fecção pelo HIV. Brasília, 2018, 416 p. Disponível em: http://www.aids.gov.br/pt-br/tags/publicacoes/protocolo-clinico-e- diretrizes-terapeutica. Acesso em: 16 abr. 2020.

BERTOLA, Alexandra. Risco de Aids em transfusão apavora pacientes. O Globo, Rio de Janeiro, 15 fev. 1987. Caderno. Grande Rio, p. 21. Disponível em: 2http://acervo.oglobo.globo.com/busca/?tipoConteudo=pagina&or- denacaoData=relevancia&allwords=aids+e+transfusao&anyword=&noword=&exa- ctword=&decadaSelecionada=1980&anoSelecionado=1987&mesSelecionado=2. Acesso em: 06 maio 2018.

CARNEIRO, Maria Luiza Tucci. O discurso da intolerância: Fontes para o estudo do racismo. In: CONGRESSO BRASILEIRO DE ARQUIVOLOGIA, 10., 1994, São Paulo. Anais… São Paulo: Congresso Brasileiro de Arquivologia, 1994.

COHEN, Sandra. Aidéticos e a longa espera por um leito. O Globo, Rio de Janeiro, 09 abr. 1989. Caderno. Rio, p. 20.

Disponível em: C%A4http://acervo.oglobo.globo.com/busca/?tipoConteudo=pa- gina&ordenacaoData=relevancia&allwords=aid%C3%A9ticos+e+leito&any- word=&noword=&exactword=&decadaSelecionada=1980&anoSelecio- nado=1989&mesSelecionado=4. Acesso em: 06 maio 2018.

Costureiro Markito morre de ‘câncer-gay’ em Nova York. O Globo, Rio de Janeiro, 5 jun. 1983.

DARDE, V. W. S. As representações de cidadania de gays, lésbicas, bissexu- ais, travestis e transexuais no discurso jornalístico da Folha e do Estadão. 2012. 230 f. Tese (Doutorado em comunicação) – Faculdade de Biblioteconomia e Comunicação, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, 2012. Disponível em: https://www.lume.ufrgs.br/bitstream/han- dle/10183/54524/000850909.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Acesso em: 17 abr. 2020.

DIEHL, Leandro. et al. Prevalência da lipodistrofia associada ao HIV em pacientes ambulatoriais brasileiros: relação com síndrome metabólica e fatores de risco car- diovascular. Arquivo Brasileiro de Endocrinologia Metabólica, São Paulo, 52(, n. 4, p. 658-667, jun. 2008. Disponível em: http://saudepublica.bvs.br/pesquisa/re- source/pt/lil-485832. Acesso em: 15 abr. 2020.

GALLIAN, Dante Marcello Claramonte. A (re) humanização da medicina. [2001]. Centro de História e Filosofia das Ciências da Saúde da Unifesp-EPM. Disponível em:<http://www2.unifesp.br/dpsiq/polbr/ppm/especial02a.htm>. Acesso em: 20 mar. 2020.

GOMES, Antonio Marcos Tosoli; SILVA, Érika Machado Pinto; OLIVEIRA, Denize Cristina de. Representações sociais da AIDS para pessoas que vivem com HIV e suas interfaces cotidianas. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, Ribeirão Preto, v. 19, n. 3, p. 485-492, jun. 2011. Disponível em: <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0104- 11692011000300006&lng=en&nrm=iso>. Acesso em: 17 abr. 2020

GOFFMAN, Erving. Estigma: notas sobre a manipulação da identidade deterio- rada. 4. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 1982. 158 p.

GIANOTTI, Rolland. Vítimas do vírus do preconceito. O Globo, Rio de Janeiro, 09 abr. 1997. Caderno Rio, p. 16. Disponível em: http://acervo.oglobo.globo.com/bu- sca/?tipoConteudo=pagina&ordenacaoData=relevancia&allwords=virus+do+pre- conceito&anyword=&noword=&exactword=&decadaSelecionada=1990&anoSele- cionado=1997. Acesso em: 05 maio 2018.

HEUSI não punirá legistas que se negam a necropsiar os aidéticos. O Globo, Rio de Janeiro, 24 jun. 1987. Caderno Grande Rio, p. 9. Disponível em:<http://acervo.oglobo.globo.com/busca/?tipoConteudo=pagina&ordenacao- Data=relevancia&allwords=heusi+e+legistas&anyword=&noword=&exact- word=&decadaSelecionada=1980>. Acesso em: 06 maio 2018.

JORGE, Thaís de mendonça. Valor-notícia provoca polêmica. In: ______. Manual do Foca: guia de sobrevivência para jornalistas. São Paulo: Contexto, 2015. p. 27- 38.

LOPES, Antônio Carlos. Relação médico – paciente: humanização é fundamental. Sociedade Brasileira Clínica Médica [Site]. Disponível em: http://www.sbcm.org.br/v2/index.php/artigo/2038-relacao-medico-paciente-hu-manizacao-e-fundamental. Acesso em: 15 abr. 2020.

LOBATO, Eliane. Nem tudo é drama. O Globo, Rio de Janeiro, 12 jun. 1987. Se- gundo Caderno, p. 5. Disponível em: C%A6http://acervo.oglobo.globo.com/bu- sca/?tipoConteudo=pagina&ordenacaoData=relevan- cia&allwords=nem+tudo+%C3%A9+drama&anyword=&noword=&exactword=&de- cadaSelecionada=1980&anoSelecionado=1987&mesSelecionado=6&diaSelecio- nado=12. Acesso em: 05 maio 2018.

LUCAS, Vera. Conscientização e respeito. O Globo, Rio de Janeiro, 28 out. 1990. Cad. Segundo Caderno, p. 7. Disponível em: http://acervo.oglobo.globo.com/bu- sca/?tipoConteudo=pagina&ordenacaoData=relevancia&allwords=lu- cinha+araujo&anyword=&noword=&exactword=&decadaSelecionada=1990&ano- Selecionado=1990&mesSelecionado=10. Acesso em: 06 maio 2018.

MARQUES, Maria Cristina da Costa. Saúde e poder: a emergência política da Aids/HIV no Brasil. História, Ciências, Saúde, Rio de Janeiro, v. 9, p. 42-65, 2002. Suplemento. Disponível em:<http://www.scielo.br/pdf/hcsm/v9s0/02.pdf.>. Acesso em: 21 set. 2017.

SEIDL, Eliane Maria Fleury; machado, Ana Cláudia Almeida. Bem-estar psicológico, enfrentamento e lipodistrofia em pessoas vivendo com HIV/AIDS. Psicologia em Estudo, Maringá, v. 13, n. 2, p. 239-247, abr./jun.2008. Disponível em:<http://www.scielo.br/pdf/pe/v13n2/a06v13n2>. Acesso em: 21 set. 2017.

SPINK, Mary Jane. et al. A construção da AIDS-notícia. Cad. Saúde Pública, Rio de Janeiro, v. 17, n, 4, p. 851-862, jul./-ago. 2001. Disponível em: https://www.re- searchgate.net/profile/Mary_Spink/publication/26359601_A_construcao_da_AIDS- noticia/links/540f63d90cf2f2b29a3ddd9e.pdf. Acesso em: 16 abr. 2020.

ZYGLAND, Fanny. Famílias rejeitam doentes com Aids. O Globo, Rio de Janeiro, 29 maio 1988. Caderno O País, p. 10. Disponível em: http://acervo.oglobo.globo.com/busca/?busca=fanny+zygland. Acesso em: 06 maio 2018.

APPENDIX – FOOTNOTE REFERENCES

4. Here, the label appears. It is with this weight that the positivity of an HIV test is attributed. Greater weight may fall on the individual receiving the diagnosis. Stigma and discrimination can accompany this situation, leading to the elaboration of a sentence: carrying a chronic disease, surrounded by fear and still without cure.

5. The institution of antiretroviral therapy (ART) aims to reduce the morbidity and mortality of people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA), improving quality and life expectancy.

[1] PhD student of the Graduate Program in Human and Social Sciences of the Federal University of ABC; Master’s degree in HumanIties from Santo Amaro University.

[2] Advisor. PhD in Sociology and Social Sciences. Master’s degree in Sociology and Human Sciences. Graduation in Social Sciences.

[3] Co-advisor. Doctorate in History. Graduation in History.

Sent: April, 2020.

Approved: August, 2020.