INTEGRATIVE REVIEW

LOPES, Lorena Machado [1], DIAS, Sonia Maria [2]

LOPES, Lorena Machado. DIAS, Sonia Maria. Dressing and undressing: Procedures to prevent contamination by the new coronavirus. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 05, Ed. 12, Vol. 05, p. 154-178. December 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/health/dressing

ABSTRACT

This study outlined the following objectives: to identify divergences and similarities in the guidelines/determinations listed in the literature on dressing and undressing and to summarize the consensus for the appropriate steps to carry out the listed procedures based on the literary texts. We sought to answer the problem-question that concerns: what are the operational procedures evidenced in the Brazilian and international literature, oriented towards dressing and undressing, in order to avoid the infection of the health professional by the new coronavirus. The methodology adopted was a systematic integrative literature review. For the collection of information, the database of the Virtual Health Library was used and the electronic platforms of public agencies were included. The model adapted to the prism method was used to select the identified literature, being delimited in publications from the year 2020 due to the declaration, this year, of the pandemic by the new coronavirus by the World Health Organization. The results showed a diverse set of personal protective equipment necessary for the protection of health professionals and the existence of similar steps for the procedures of dressing and undressing. For the final considerations, the sequential order for the execution of the investigated procedures was summarized, to be adopted by the health professional to prevent contamination, especially here, by the new coronavirus.

Keywords: Coronavirus, health professionals, infection control.

INTRODUCTION

The pandemic evidenced by the action of the new coronavirus, which causes the disease called COVID-19 (Corona Virus Disease), had the first official case in China in December 2019, building a route of transmission of the virus, although unknown, but that spread to several countries on the continents. It is a global public health emergency, which has altered the routine of people’s lives around the world. The change in people’s way of living is due to the high transmissibility of the virus, sometimes, as a consequence, for people recovered from COVID-19 and loss of life in situations of severe clinical conditions (VELAVAN, 2020).

The number of cases of the disease changes daily and it is possible to detect it in real time. From March 2020, when the presence of a pandemic was recognized by the World Health Organization – WHO, until the month of September of the current year, a public body points out the following data. The Ministry of Health’s Special Epidemiological Bulletin (referring to Epidemiological Week (SE) 36 – period from 08/30/20 to 09/05/20) brings a total of 26,640,898 confirmed cases of COVID-19 worldwide. The United States was the country with the highest number of cumulative cases (6,201,726), followed by Brazil (4,123,000), India (4,023,179), Russia (1,015,105) and Peru (676,848). In relation to deaths, and until that same date, the statistics show a total of 874,967 in the world, with the United States being the country with the highest accumulated number of deaths (187,765), followed by Brazil (126,203), India (69,561), Mexico (66,851) and United Kingdom (41,537) (MS, 2020). This indicates the magnitude of transmissibility of the new coronavirus and the consequences of COVID-19.

Because COVID-19 is a new disease, and so far, there is no effective vaccine available, all people are susceptible to infection, especially healthcare professionals as they are on the front line of caring for infected patients (ANVISA, 2020a). According to data provided by the Federal Nursing Council (COFEN), by mid-September 2020, 38,750 cases of infection with the new coronavirus were reported in nursing professionals, and among these cases, 395 evolved to death (COFEN, 2020). These numbers reflect the occupational risk to which health professionals are subjected, especially in the face of a new disease.

Professionals during the performance of their activities, in addition to being exposed to the risk of infection by the new coronavirus, are susceptible to the stress associated with providing direct care to suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients. A cross-sectional study evaluated 16,630 health professionals regarding mental status and sleep quality and demonstrated depression in 14%-15%; anxiety in 12%-24%; 30%-39% with psychological disorders and 8%-60% with sleep disorders (ANVISA, 2020a).

The concern regarding the safety/well-being of health professionals is mainly due to two factors, the first is that the removal of a large number of employees from the service reduces its capacity, generating an even greater overload on the health service system. In addition, once infected by the disease, and in the case of undiagnosed and isolated, these professionals can act as vectors in the spread of the virus to other patients, family members and the community in general (VERBEEK et al, 2020).

According to the WHO global network of experts, transmission of the new coronavirus occurs mainly through respiratory droplets (expelled during speech, coughing or sneezing) from infected people to other people who are in close contact, through direct contact with the virus infected person or by contact with contaminated objects and surfaces. In addition, scientific evidence of the potential for transmission of COVID-19 has been accumulating, mainly through inhalation of the virus through aerosol particles generated during hospital procedures, such as during direct manipulation of the airway, intubation and extubation of patients in aspiration procedures (ANVISA, 2020a).

The use of personal protective equipment (PPE) is the most suitable method of control to prevent the spread of infection during health care, however, it is only one of the prevention and control measures, retaining limited benefits, needing to be associated with strategies prevention measures, such as frequent hand hygiene, routine cleaning and disinfection of the environment and surfaces, social distancing, among others (WHO, 2020b).

For these equipment to be effective in reducing the risk of infection, the indication of use, handling, removal, disposal and among other specificities must be carefully observed, always considering the current scientific evidence available and the guidelines of health agencies. It is essential that health professionals be offered training and continuing education activities on the new coronavirus and infection prevention and control guidelines, especially regarding the correct management of PPE and its specifications (HOUGHTON et al, 2020).

Considering the importance of personal protective equipment in the context of the biosafety of health professionals, this study seeks to answer the following question: What are the operational procedures evidenced in the Brazilian and international literature, oriented towards dressing and undressing, in order to avoid infection of the health professional by the new coronavirus?

To answer this question, this study outlined the following objective(s):

Identify divergences and similarities in the guidelines/determinations listed in the literature on dressing and undressing.

Summarize the consensus for the steps of the dressing and undressing procedures based on the texts selected for the integrative review.

METHODOLOGY

This is a systematic literature review of the integrative type that used explicit and systematic methods described by Souza, Silva and Carvalho, which has the following structure: elaboration of the guiding question; search or sampling in the literature; data collect; critical analysis of included studies; discussion of results; presentation of the integrative review (SOUZA, 2010).

The following research question, already mentioned above, was elaborated: What are the operational procedures evidenced in the Brazilian and international literature, oriented towards dressing and undressing, in order to prevent the infection of health professionals by the novel coronavirus?

The option for the systematic method of integrative review aims to analyze the knowledge built and disseminated in the various vehicles for publications, and this knowledge materialized in the past, can generate new knowledge for the development of science.

Data analysis sought to determine which operational procedures are oriented towards the attire and undressing of the professional who provides assistance to people with suspected and/or confirmed COVID-19, in order to avoid contamination by the new coronavirus. The results were compared with each other, in order to identify differences and similarities in the guidelines/determinations described in the published texts.

The literature search was carried out between the 20th of July and the 10th of September 2020. Literature published in the year 2020 was included in the search, as this was the date on which the new coronavirus pandemic was declared by the World Health Organization (OMS/OPAS, 2020). The Virtual Health Library (VHL) was used as a basis for the search for data because it covers the field of health.

CRITERIA USED FOR THE INCLUSION OF STUDIES IN THIS RESEARCH

As the name implies, the new coronavirus is a virus that emerged recently and had a rapid worldwide spread, which resulted in the current pandemic in which we live. Despite worldwide efforts, knowledge about some variables of the virus is still scarce, limiting the development of studies.

Considering this mentioned limitation and the objective(s) proposed in this study, only systematic literature review articles were included. In addition, since the intention of this study, in general, is to discuss operational procedures aimed at the biosafety of health professionals who deal with users of suspected and/or confirmed COVID-19 hospital services, it was judged as necessary to include official publications of guidelines from Brazilian and international health agencies.

CRITERIA USED FOR THE EXCLUSION OF STUDIES IN THIS RESEARCH

Studies that did not include the listed descriptors were disregarded. Those who, despite meeting the descriptors, were not available in full, and those who did not have free access for payment for reading, dissertations and theses were also disregarded.

SEARCH METHOD TO IDENTIFY ELIGIBLE PUBLICATIONS

ELECTRONIC SEARCH IN JOURNALS

A systematic literature search was performed to identify all qualitative systematic publications that could be considered eligible for inclusion in this work. The search carried out in the Virtual Health Library (VHL) was carried out through the previously selected descriptors, according to the Health Sciences Descriptors (DeCS) platform, culminating in the following chosen terms: Coronavirus, Health Professionals and Infection Control.

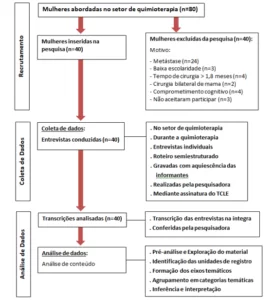

The tracking of constructed knowledge was guided by a flow, in order to highlight those texts that fit the topic to be studied. It should be clarified that the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA) method served to guide the organization of the search for scientific production (GALVÃO, 2015).

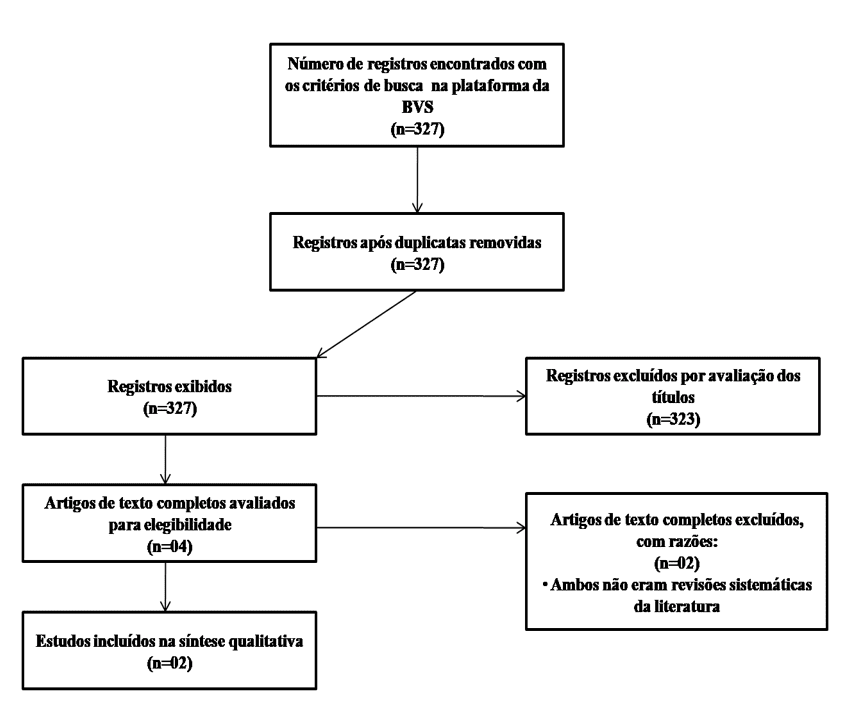

Two search strategies were carried out in the journal, the first being as follows:

- Descriptors used in the search: Coronavirus AND “Health professionals”.

- Selected filters:

Languages: Portuguese, English and Spanish;

Year of publication: 2020;

Document type: Full article available.

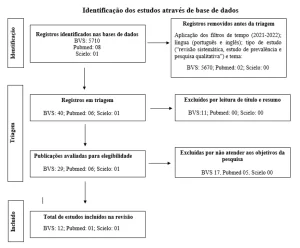

The strategy is described in flowchart I (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Flowchart of the selection process of studies I, adapted from PRISMA.

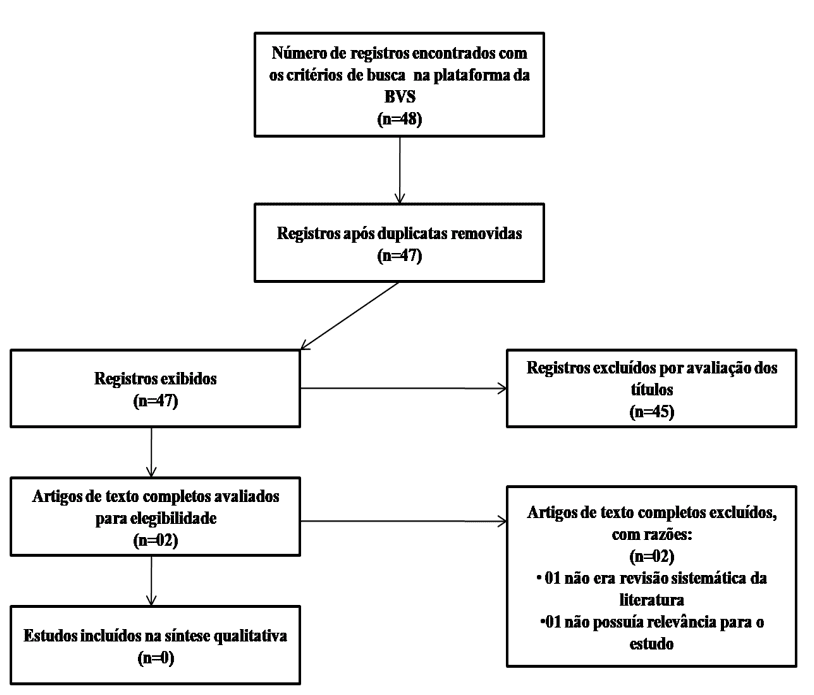

The second search strategy for research in the journal considered:

The second search strategy for research in the journal considered:

- Descriptors: Coronavirus AND “Healthcare workers” AND “Infection control”.

- Selected filters:

Languages: Portuguese, English and Spanish;

Year of publication: 2020;

Document type: Full article available.

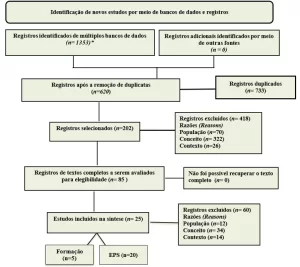

The second strategy is described in flowchart II (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Flowchart of the selection process of studies II, adapted from PRISMA.

ELECTRONIC SEARCH ON HEALTH BODIES PLATFORMS

Official publications found on the websites of health bodies considered national and international references in the fight against the new coronavirus were included in this study, they are:

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

- World Health Organization (WHO)

- National Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA)

- Brazilian Association of Intensive Medicine (AMIB)

- Ministry of Health (MS)

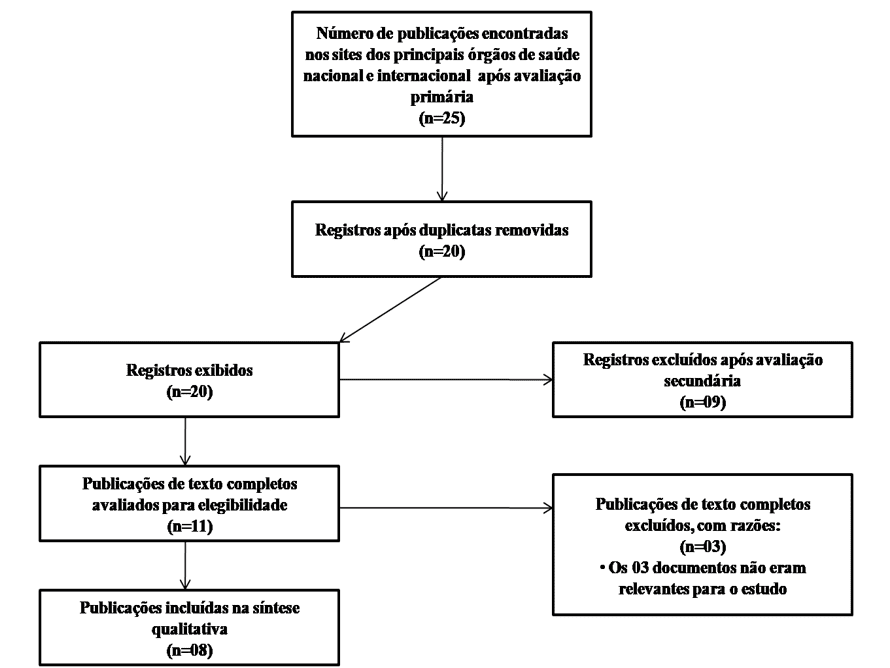

The selection of documents was carried out in three main steps:

1. Primary assessment of the document title:

Does the title relate to the new coronavirus and/or the use of personal protective equipment (PPE)?

2. Secondary rating:

Analysis of the title, abstract and/or summary of the document: do these items provide information about health professionals and/or infection prevention and control?

Year of publication: Was it published in 2020?

3. Tertiary assessment:

After this first screening, the selected documents were read in full, and the following criteria were used for inclusion:

Is the content of the document relevant to the object of study of this work? The strategy is described in flowchart III (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Flowchart of the publication selection process III, adapted from PRISMA.

A total of 371 articles were identified in the database, and a total of 368 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria and/or did not answer the guiding question of the research, and duplicates were also removed. The 06 selected studies were submitted to full reading and after this moment, 04 articles were excluded, according to the established exclusion criteria. 02 articles were chosen to compose the integrative review. Regarding the guidelines of public bodies, a total of 08 were part of the set of selected texts.

RESULTS

CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE INCLUDED STUDIES

Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 10 references were added, symbolized by the letter R followed by a number, as shown in the table below. The selected texts were grouped at level IV of the classification by Souza, Silva and Carvalho for evidence-based practice, as it covers studies with a qualitative approach (SOUZA, 2010). The synthetic compilation of these documents is shown in Table 1, characterized by the numbered reference, authors and year of publication, country of origin of the text, title and summary of the results.

Table 1 – Studies found according to authorship and year of publication, country, title, summary of results

| References | Authors and year | Country | Title | Abstract of results |

| R1 | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020 | USA | Using Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | This document guides how healthcare professionals should put on and take off PPE:

Placement / paramentation: 1st identification and collection of the necessary PPE; 2nd hand hygiene; 3rd apron/coat; 4th surgical mask or N95/PFF2; 5th face shield or goggles; 6th gloves; 7th the professional can now enter the patient’s room. Removal/Undressing: 1st gloves; 2nd apron/coat; 3rd the professional can now leave the patient’s room; 4th hand hygiene; 5th face shield or goggles; 6th surgical mask or N95/PFF2; 7th Hand hygiene. *Facilities implementing reuse or extended use of PPE must adjust their donning and doffing procedures to accommodate these practices. |

| R2 | World Health Organization, 2020 | USA | Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and considerations during severe shortages | The document brings three main strategies to optimize the availability of PPE:

1st Minimize the need to use this equipment through strategies such as the use of telemedicine for the initial assessment of suspected patients, reducing the number of professionals in risk areas, simplifying the workflow, etc.; 2nd Ensure the rational and appropriate use of PPE through indication of use based on configuration, target audience, risk of exposure and transmission dynamics of the pathogen; 3rd Coordination of PPE supply chain management. *The PPE to which the publication refers are: gloves, surgical masks or N95/PFF2, goggles or face shield/face shield and aprons. The document also summarizes the temporary measures that can be adopted in the context of severe shortages of PPE or lack of stock according to the place, person/profession and type of activity. |

| R3 | World Health Organization, 2020 | USA | HOW TO PUT ON AND TAKE OFF Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) | This publication defines:

Dressing guide: 1st hand hygiene with soap and water or alcohol; 2nd placement of the apron/coat; 3rd placement of the surgical mask or N95/PFF2; 4th placement of the face shield or goggles; 5th placement of gloves. Undressing Guide: 1st removal of gloves; 2nd removal of the apron/coat; 3rd hand hygiene; 4th removal of the face shield or goggles; 5th removal of the mask; 6th hand hygiene. |

| R4 | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020 | USA | Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Healthcare Personnel During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic Infection Control Guidance | The document brings the responsibility of the health institution to define and describe policies and procedures related to the safe sequence of putting on and taking off PPE. In the case of reusable PPE, the institution is also responsible for determining how cleaning, disinfection and the way in which it will be stored between uses will be carried out.

The PPE’s that must be used by the professional providing care to a patient with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 are: Respirator (N95, PFF2 or equivalent) or surgical mask: put on before entering the patient room or care area, remove and discard after leaving the room or care area (except for prolonged use or reuse), then perform hand hygiene; Eye protection/face shield: put on before entering the room or care area and remove after leaving the room; Procedure gloves: should be put on when entering the room or care area, changing in case of tear or excessive contamination. Remove and discard before leaving the room or care area, with hand hygiene immediately after; Apron/coat: put on before entering the room or care area, change it in case of significant soiling. Removal and disposal must occur before leaving the environment. In case of disposable coats, discard them in the infectious waste, if the apron is made of cloth, it must be sent for washing/disinfection after each use |

| R5 | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020 | USA | Interim Operational Considerations for Public Health Management of Healthcare Workers Exposed to or with Suspected or Confirmed COVID-19: non-U.S. Healthcare Settings | This document provides operational considerations to assist health services in managing professionals exposed to people with suspected or confirmed COVID-19. However, it does not provide specific recommendations on the use of personal protective equipment, it only points out the need to use surgical masks or N95/PFF2 by all professionals, aiming at universal source control.

The document also defines what is high and low risk exposure, concepts relevant to the development of this study: High-risk exposure: close contact with a person with COVID-19 in the community; OR providing direct care to a patient with COVID-19 without using adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) or not performing adequate hand hygiene following these interactions; OR come into contact with the infectious secretions of a COVID-19 patient or contaminated patient care environment, without wearing proper personal protective equipment (PPE) or not performing proper hand hygiene. Low-Risk Exposure: Contact with a person with COVID-19 who has not met high-risk exposure criteria (e.g., brief interactions with COVID-19 patients in the hospital or community). |

| R6 | Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária, 2020 | Brazil | NOTA TÉCNICA Nº 12/2020/SEI/GGTES/DIRE1/ANVISA Manifestação sobre o processamento (reprocessamento) de Equipamentos de Proteção Individual (EPIs) | This file does not provide specific recommendations on the process of dressing and undressing, but addresses the reprocessing of personal protective equipment, a topic that is relevant to the process of putting on and taking off PPE.

There is, for the time being, no consistent scientific evidence to ensure the effectiveness and safety of reusing a framed PPE. as “PROHIBITED REPROCESSING” or “THE MANUFACTURER RECOMMENDS SINGLE USE”, so that both the decision and the responsibility for processing these products are the responsibility of the health service and the processing company, as established in the health regulations on the subject. Authorization from ANVISA or the local health surveillance agency is not required for this process. However, it is important to highlight that reprocessing should only be adopted when a safe and feasible procedure demonstrates equivalence to a new health product. Finally, considering the great demand for N95, PFF2 and equivalent respiratory protection masks caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the possibility of scarcity of this PPE in the market, it is guaranteed, exceptionally, the use of these masks for a longer period or for a times greater than that provided for by the manufacturer, provided that they are used by the same professional and that the recommendations described in the Technical Note GVIMS/GGTES/ANVISA N. 04/2020 (31.03.2020) are followed. |

| R7 | Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária, 2020 | Brazil | NOTA TÉCNICA GVIMS/GGTES/ANVISA Nº 07/2020 Orientações para prevenção e vigilância Epidemiológica das infecções por sars- cov-2 (COVID-19) dentro dos serviços de saúde. | The note defines that the type of PPE used in patient care varies according to the type of care provided, the risk of exposure and the activity performed. In the case of a room, area, ward or box of suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients, healthcare professionals should use during the provision of care:

Glasses or face shield; Surgical mask (N95/PFF2 in case of aerosol-generating procedures); Apron/coat; procedure gloves; Disposable cap (in case of aerosol generating procedures). *There is no information on the procedure for putting on and taking off these PPE. The document defines the responsibility of the local manager to supply this equipment to the workers, in an appropriate way and in sufficient quantity. The implementation of training on the use of this equipment is also the responsibility of the manager. |

| R8 | Associação de Medicina Intensiva Brasileira, 2020 | Brazil | Recomendações da Associação de Medicina Intensiva Brasileira (AMIB) para a abordagem do COVID-19 em medicina intensiva | The following step-by-step procedure is described for the placement of PPE: 1st hand hygiene;

2nd cap; 3rd goggles or visor (face shield); 4th surgical mask or N95/PFF2 mask; 5th apron/coat; 6th procedure gloves. The document does not provide recommendations on how the worker should perform the undressing. |

| R9 | Petrosillo, Nicola, et al., 2020 | USA | Barriers and facilitators to healthcare workers’ adherence with infection prevention and control (IPC) guidelines for respiratory infectious diseases: a rapid qualitative evidence synthesis (Review) | Despite not reaching a consensus on the best method of dressing and undressing, the article points out three variables as responsible for low rates of adherence to the correct use of PPE, the first variable being the lack of specific guidelines for COVID-19, in the second the non-compulsory training on the subject, and finally the lack of performance evaluations in the practice of these professionals. |

| R10 | Verbeek, Jos H., et al., 2020 | USA | Personal protective equipment for preventing highly infectious diseases due to exposure to contaminated body fluids in healthcare staff (Review) | The article brings that the rates of professional contamination by contaminated fluids are not only determined by the type of personal protective equipment, but also by the procedures for placing and removing them. It also associates the improper removal of this equipment with self-contamination and a greater risk of infection.

*It should be noted that the certainty of the evidence is low to very low because the conclusions are based on one or two small studies and a high or unclear risk of bias. |

Source: The authors, 2020

All documents were published in 2020, with R9 and R10 being articles and other documents from national and international health bodies. They are: the National Health Surveillance Agency, the Brazilian Intensive Medicine Association, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization. It is worth mentioning that the procedures for dressing and undressing are techniques known and performed in daily professional practice. However, this topic represents a concern of scholars with regard to protective care against contamination by microorganisms harmful to health, especially the new coronavirus. This may have mobilized their interest in highlighting the relevance of the theme, as well as the investigation interest of this research.

DISCUSSION

The results obtained showed diversified highlights. Focuses were found regarding PPE (Individual Protection Equipment), and about the steps for putting on and undressing, approaches that were constituted in categories to systematize the discussion of the results.

By understanding the relevance of the theme for the safety of professionals and users in health services and in order to prevent contamination in this case, by the coronavirus, the need to highlight the proposed objective(s) was realized in order to point out the divergences and similarities in the guidelines/determinations listed in the literature on the procedures for dressing and undressing, to summarize the consensus of execution of the mentioned procedures, in addition to scoring the other approaches found in the texts raised that are of high importance. In view of the above, we will now focus on the categories constituted by this investigation.

CATEGORY A PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT (PPE)

PPE is used to protect the healthcare worker from infected individuals, potentially infectious surfaces, materials and products, and other potentially hazardous substances used during care delivery. Therefore, every professional must receive training and demonstrate the ability to use this equipment safely, being able to identify when and which PPE is necessary for each situation; how to wear it, use it and remove it properly in order to avoid self-contamination; how to discard or disinfect, how to store it after use and what are its limitations (ANVISA, 2020a).

Most of the documents used in this study (R1, R2, R3, R4, R9 and R10) recommend the use of the following PPE by the professional who provides care to a patient with suspected or confirmed COVID-19:

- N95, PFF2 or equivalent respirator (in case of aerosol-generating procedures) or surgical mask (other procedures);

- Eye protection or face shield;

- Procedure gloves;

- Apron/coat.

The National Health Surveillance Agency (R7) and the Brazilian Intensive Medicine Association (R8) also recommend this equipment, however, they include the disposable cap as a necessary PPE. However, ANVISA recommends it only in case of procedures capable of generating aerosols, while AMIB proposes its use in all care procedures, in front of suspected or confirmed patients regarding contamination by COVID-19.

Some considerations should be made about some of these equipment:

SURGICAL MASK

As part of the efforts to control the source and for the personal protection of the professional, it is recommended that the same make use of the surgical mask for the entire period of stay in the health service. In case of shortage of equipment, priority in the use of PPE should be given to professionals who provide assistance or have direct contact, less than 1 meter, with patients. On the other hand, professionals whose work functions do not require the use of PPE, such as exclusively administrative personnel or who work in areas with contact greater than 1 meter from patients, must wear fabric masks while they are in the institution, as the control of source will be similar to that indicated for the general population (ANVISA, 2020a).

RESPIRATORY PROTECTION MASKS (PARTICULATE RESPIRATOR)

These are masks that have minimal filtration efficiency (they filter 95% of particles up to 0.3μM), they are the N95, N99, N100, PFF2 or PFF3 type. They should be used whenever aerosol-generating procedures are performed, such as intubation or tracheal aspiration, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and others (AMIB, 2020). However, if these models of masks are provided with an expiratory valve, they should not be used by professionals, for the reason that this device filters the aspirated air, but allows the professional to exhale the air, so in the event of being infected, it would contaminate the environment, other professionals and patients. It so happens that due to the current perspective of the COVID-19 pandemic and the possibility of a shortage of PPE, the mask with an expiratory valve can be used if associated with a face shield. This mitigation measure should not be applied in the Surgical Center, due to the increased risk of contamination of the surgical wound through droplets expelled by professionals (ANVISA, 2020a).

EYE PROTECTION OR FACE PROTECTOR/FACE SHIELD

The equipment must cover the front and sides of the face and its use must be exclusive to a professional (AMIB, 2020). In case of reuse, the equipment must be cleaned, disinfected and packaged according to the manufacturer’s reprocessing instructions (CDC, 2020a).

It is necessary to ensure that the PPE is compatible with the respirator or mask used, so that it does not interfere with the correct placement of eye protection or the fit/seal of the respirator or mask. Goggles with spaces between the glasses and the face are unlikely to protect the eyes from all splashes and sprays (CDC, 2020a).

PROCEDURE GLOVES

They should be used when there is a risk of contact of the professional’s hands with blood, body fluids, excretions, mucous membranes, secretions, non-intact skin and contaminated articles or equipment, in order to reduce the possibility of transmission of the new coronavirus to the health worker, as well as from patient to patient through the hands of the professional (AMIB, 2020).

APRON/COAT

The equipment must be waterproof and used during procedures with risk of blood spatter, body fluids, secretions and excretions, and other situations that may result in contamination of the professional’s skin and clothing (AMIB, 2020).

It is recommended that the apron/coat have long sleeves, a mesh or elastic cuff and a back opening, and be able to provide an effective antimicrobial barrier (AMIB, 2020). However, it is worth noting that covering more parts of the body leads to better protection, but generally complicates donning and doffing procedures, in addition to reducing user comfort, which can then increase the risk of contamination (VERBEEK et al, 2020).

Regarding the work process, the health service must develop strategies that seek to minimize the need for the use of personal protective equipment, using, for example, telemedicine for the initial evaluation of suspected patients, reducing the number of professionals in the areas of risk, workflow simplification and others (WHO, 2020b).

In addition, it is also up to the service to define and describe the policies and procedures related to the safe sequence of placement and removal of PPE, prolonged use and/or reprocessing of the same, in addition to the cleaning, disinfection process and the way of packaging between uses. These responsibilities were evidenced in 03 (three) of the documents analyzed (R4, R6 and R7). Recommendations from health agencies and current scientific evidence should be used as a basis for defining these procedures (CDC, 2020a).

CATEGORY B WEARING AND DISTINGUISHING – SIMILARITIES AND DIVERGENCES FOUND IN THE PROCEDURES

This category was centered on the focus of the first proposed objective. In view of the results obtained in this study, it was necessary to dismember the category into three parts, constituting sub-categories to understand the specificities that pertain to each of the procedures. The first part focused on the similarity of steps for the attire, followed by the second part occupied by their divergence. The third part was limited to identifying the similarities of the steps for undressing. Once divergences for undressing were not identified, the discussion of the data obtained remained within the limit of the three subcategories indicated.

SUB CATEGORY B.I) SIMILARITIES OF STEPS FOR DRESSING

Regarding how the professional should perform the attire, two of the publications (R1 and R3) have similar recommendations and guide the following order of placement of PPE

- Apron/coat;

- Surgical mask or N95/PFF2;

- Face shield/face shield or goggles;

- Gloves.

In addition, both emphasize the need to perform hand hygiene, with 70% alcohol or soap and water, before starting the process of dressing.

The reference identified as R4 does not indicate a specific order for the attire, it only determines the equipment that must be placed before entering the patient’s room or care area, namely: respirator (N95, PFF2 or equivalent) or surgical mask, eye protection /face shield and apron/coat. Procedure gloves should be donned when entering the room or care area.

SUB CATEGORY B.II) DIVERGENCES OF STEPS FOR DRESSING

The reference identified as R8, on the other hand, presents a divergence with respect to the outfitting sequence, it proposes the following order:

- cap;

- Goggles or visor (face shield);

- Surgical mask or N95/PFF2 mask;

- Apron/coat;

- Procedure gloves.

The need for hand hygiene before placing the equipment is also evidenced by the document.

SUB CATEGORY C.III) SIMILARITIES OF STEPS FOR WEARING OUT

The inappropriate or excessive use of PPE generates an additional impact on the shortage of supplies and the risk of contamination of the professional, especially at the time of undressing. Therefore, this process must be described a priori in order to allow training to be carried out and the solution of possible doubts (ANVISA, 2020a).

Only references R1 and R3 define a similar order for the removal of personal protective equipment, which is as follows:

- Gloves;

- Apron/coat;

- Face shield or goggles;

- Surgical mask or N95/PFF2.

When comparing the risks of contamination of removing the coat/apron and the glove in a single step versus removing the glove and then the coat/apron, a study showed a lower rate of contamination in the latter technique (VERBEEK et al, 2020).

Now, regarding the times when each piece of equipment must be removed, references R1 and R4, guide that the professional must remove gloves and coat/apron before leaving the room or care area, performing hand hygiene afterwards. And only after leaving the environment, you should remove the respirator or mask and eye protection / face shield, proceeding again with hand hygiene.

During the removal of the mask, the professional must be attentive to carry out the removal through the straps, avoiding touching the equipment. And when removing the apron/coat, make sure to perform the movement gently, carefully pulling the PPE down and away from the body. These guidelines were better highlighted in references R1 and R3.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Regarding the biosecurity of health professionals who provide care to patients with suspected and/or confirmed infection with the new coronavirus, personal protective equipment is considered essential. Although the use of clothing consisting of an apron, hat, mask, glasses and gloves, is common attire in surgical spaces and other services that assist people with communicable diseases, and is still a teaching and learning theme included in the academic curriculum, there was concern of scholars in highlighting personal protective equipment and the sequence of procedures for dressing and undressing resulting from the current world health scenario.

With this in mind, this study sought to identify the differences and similarities regarding the procedures for putting on and undressing the health professional, and in the end, to summarize the consensus for carrying out the mentioned procedures based on the texts selected for the integrative review, which were significant for obtaining the results from which the contributions of this study originated.

The healthcare professional providing assistance to suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients must use these personal protective equipment: surgical mask or N95/PFF2 or equivalent; eye protection or face shield (face shield); procedure gloves; apron/coat. Some authors also recommend the disposable cap as essential PPE and, if available, should be used.

Thinking about the practicality for the process of putting on and taking off PPE and considering all the recommendations analyzed during this study, the following standard operating procedure was created for the attire and undressing of the health professional:

Dressing

Step 1st: hand hygiene with alcohol or soap and water;

Step 2nd: placement of the apron/coat;

Step 3th: placement of the surgical mask or N95/PFF2 or equivalent;

Step 4th: placement of the disposable cap;

Step 5th: placement of eye protection or face shield – the choice of equipment must consider the mask used;

Step 6th: Placement of procedure gloves.

It is important to highlight that the attire must occur before entering the care area and/or the patient’s room, only gloves can be placed inside the environment.

Undressing

Step 1st: removal and disposal of the procedure glove;

Step 2nd: removal and disposal of the apron/coat – the knots or buttons must be loosened and the apron pulled gently by the shoulder, down and away from the body;

These first two steps must be performed within the patient’s care area and/or room, and at the end, the professional can leave the environment.

Step 3th: hand hygiene with soap and water;

Step 4th: removal of goggles or face shield (face shield) – must be removed by the handles and pulled forward and upward, the front of the equipment must not be touched. In case of reuse and/or prolonged use, the equipment must be sanitized and packaged according to the institution’s protocol;

Step 5th: removal and disposal of the disposable cap;

Step 6th: removal and disposal of the surgical mask or N95/PFF2 or equivalent – removal must be carried out through the straps, never touching the front of the mask;

Step 7th: hand hygiene with 70% alcohol or soap and water.

New studies should be carried out in the light of the topic since it is a current topic, with high turnover of information and relevance to health. In terms of health, the proposal of this study for future research is to investigate in real time the behavior of the health professional when performing the techniques of dressing and undressing for the purpose of surveillance for safety at work.

REFERENCES

AMIB, Associação de Medicina Intensiva Brasileira. Recomendações da Associação de Medicina Intensiva Brasileira para a abordagem do COVID-19 em medicina intensiva. Disponível em: https://www.amib.org.br/fileadmin/user_upload/amib/2020/junho/10/Recomendacoes_AMIB- 3a_atual.-10.06.pdf Acesso em: 21 set. 2020.

ANVISA ADM. Orientações para prevenção e vigilância epidemiológica das infecções por SARS- CoV-2 (COVID-19) dentro dos serviços de saúde NOTA TÉCNICA GVIMS/GGTES/ANVISA No07/2020-Atualizadaem17/09/2020.Anvisa.gov.br.2020a.Disponível em: <https://www20.anvisa.gov.br/segurancadopaciente/index.php/alertas/item/nota-tecnica-gvims-ggtes- anvisa-n-07-2020-atualizada-em-17-09-2020?category_id=244>. Acesso em: 21 set. 2020.

ANVISA, Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Nota técnica sobre o processamento (reprocessamento) de Equipamentos de Proteção Individual No 12/2020/SEI/GGTES/DIRE1/ANVISA. [s.l.: s.n., s.d.]. Disponível em: <https://portaldeboaspraticas.iff.fiocruz.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Nota-Tecnica-12- GGTES.pdf>. Acesso em: 21 set. 2020.

BRASIL; Ministério da Saúde – MS, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. (2020). Boletim epidemiológico especial: doença pelo Coronavírus COVID-19 – semana epidemiológica 36 (30/08 a 05/09). Disponível em: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/Coronavirus/boletins-epidemiologicos- 1/set/boletim-epidemiologico-covid-30.pdf Acesso em: 11 set. 2020.

CDC. Interim Additional Guidance for Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Patients with Suspected or Confirmed COVID-19 in Outpatient Hemodialysis Facilities. 2020a. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Acesso em: 31 ago. 2020.

CDC. Using Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). 2020b. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disponível em: <https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/using-ppe.html>. Acesso em: 31 ago. 2020.

CDC. COVID-19: Operational Considerations for Non-US Settings. 2020c. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disponível em: <https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/non-us- settings/public-health-management-hcw-exposed.html>. Acesso em: 27 ago. 2020.

COFEN, Conselho Federal de Enfermagem (2020). Profissionais infectados com COVID-19. Disponível em: http://observatoriodaenfermagem.cofen.gov.br/ Acesso em: 11 set. 2020.

GALVÃO, Taís Freire; PANSANI, Thais de Souza Andrade; HARRAD, David. Principais itens para relatar Revisões sistemáticas e Meta-análises: A recomendação PRISMA. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde, 2015, 24: 335-342.

HOUGHTON, Catherine; MESKELL, Pauline; DELANEY, Hannah; et al. Barriers and facilitators to healthcare workers’ adherence with infection prevention and control (IPC) guidelines for respiratory infectious diseases: a rapid qualitative evidence synthesis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2020.

OMS, Organização Mundial da Saúde; OPAS, Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde. Folha informativa COVID-19. Disponível em: https://www.paho.org/pt Acesso em 9 out 2020.

TAVARES DE SOUZA, Marcela; DIAS DA SILVA, Michelly; DE CARVALHO, Rachel. Revisão integrativa: o que é e como fazer Integrative review: what is it? How to do it? v. 8, n. 1, p. 102–108, 2010. Disponível em: <https://www.scielo.br/pdf/eins/v8n1/pt_1679-4508-eins-8-1-0102.pdf>. Acesso em: 11 out. 2020.

VELAVAN, Thirumalaisamy P.; MEYER, Christian G. The COVID‐19 epidemic. Tropical Medicine & International Health, v. 25, n. 3, p. 278–280, 2020. Disponível em: <https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/tmi.13383>. Acesso em: 5 Nov. 2020.

VERBEEK, Jos H; RAJAMAKI, Blair; IJAZ, Sharea; et al. Personal protective equipment for preventing highly infectious diseases due to exposure to contaminated body fluids in healthcare staff. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews,2020.

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION. How to put on and take off personal protective equipment (PPE). Who.int, 2020a.

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION. Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and considerations during severe shortages: interim guidance, 6 April 2020. Who.int,2020b

[1] Nurse, Student of the Multiprofessional Residency Program in Hospital Care.

[2] Doctor in Nursing.

Sent: November, 2020.

Approved: December, 2020.