REVIEW ARTICLE

PAIXÃO, Carmen Scheyla Dettmann [1], ZORZAL, Juliano Kacio [2]

PASSION, Carmen Scheyla Dettmann. ZORZAL, Juliano Kacio. Gestational diabetes mellitus: An overview. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 05, Ed. 10, Vol. 04, pp. 05-20. October 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/health/gestational-diabetes-mellitus

ABSTRACT

The main objective of this article is to support actions on Diabetes Mellitus through pharmaceutical assistance during the gestational period. Through the analysis of the pharmaceutical literature and also through the study that deal with Diabetes Mellitus during the gestational period. The main role of pharmaceutical assistance is to design spaces for the development of assistance concerned with the health of patients during pregnancy. The methodology of this research was based on the documentary base, with analysis of the pharmaceutical literature that normalizes the rules of the Brazilian Pharmacy. Among the literatures we mention Tombini, Kitzmiller; Davidson, Bertini and other authors who promote Brazilian literature. The outcome of the present study consists of the identification of the effects and causes of Diabetes Mellitus during the gestational period and, finally, seeking to guide and clarify some attitudes in order to better guide pregnant women during the period of pregnancy.

Keywords: GDM, risk factors, care.

1. INTRODUCTION

Dysglycemia, that is, the alteration of glycemia is currently one of the greatest concerns of medicine while the woman is in the gestational period, making it one of the risk factors in pregnancy. Thus, the decrease in insulin sensitization is evident at different stages of life, but it is considered a concern while in the period of pregnancy.

Thus, a difficult endocrine-metabolic adequacy occurs during pregnancy, involving changes in insulin, as well as an increase in the response and mass of beta cells and also a small rise in glycemia, especially at the end of meals, changes in circulating phospholipid rates, fatty acids. triglycerides and cholesterol.

The most regular metabolic imbalance during pregnancy is gestational diabetes and its most prevalent presentation is determined as a change in blood glucose of any level, discovered during the period of pregnancy.

When expressing Gestational Diabetes Mellitus it is necessary to define the levels of intolerance to carbohydrates, results in elevated blood glucose of varying magnitudes, with origin or diagnosis during pregnancy. Major changes occur in the generation of energy and fat accumulation during normal pregnancy. This fat deposit is especially identified in the first half of pregnancy, while at the end there is an increase in the mother’s metabolic expenditure.

Finally, it is essential that the mother is evaluated throughout the gestational period, observing the state and blood glucose levels. In this way, weight control, diets and exercises and a periodic fasting glycemia are proposed.

2. ETIOLOGY

Diabetes Mellitus (DM) is a metabolic pathology, described as an increase in the volume of glucose in the blood resulting from deficiency in the generation and / or action of insulin. From this conformation, Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) is understood as any class of glucose intolerance, with a beginning or first finding in pregnancy.

This concept is adopted despite the administration of insulin or if the conjuncture continues after childbirth and does not eliminate the possibility that intransigence to glucose has succeeded in pregnancy. The changes identified in the maternal metabolism while the pregnancy lasts is essential in order to meet the demands of the fetus.

Another important issue is the occurrence of insulin resistance (IR) in the second part of pregnancy as an outcome of the physiological adjustment, permeated by the placental anti-insulin hormones, to ensure the adequate supply of glucose to the fetus. However, certain pregnant women who become pregnant with any degree of overweight IR and polycystic ovary syndrome, this physiological IR condition will be elevated in the peripheral tissues.

At the same time, there is a physiological need for greater insulin production, as well as the lack of capacity of the pancreas to respond to physiological IR, it helps the hyperglycemia of diverse impetuosity, accusing the GDM.

Pregnant women who are already insulin resistant do not have the ability to increase the insulin elimination rate, which is essential to meet the needs of their pregnancy. This resistance is already present in the second half of pregnancy and increases progressively until the end of the pregnancy, when it resembles the glucose intolerance seen in type 2 diabetes. Thus, insulin resistance helps the fetus’ metabolic demands (higher glucose supply) and is a result of circulating placental hormones.

The metabolic imperfection in pregnant women with GDM is their lack of capacity to produce insulin at levels necessary for the need that is maximum in the 3rd trimester, leading to an elevated concentration of postprandial glucose deficient to cause symptoms, but capable of establishing adverse effects on fetus (neonatal hypoglycemia and macrosomia) due to too much transplacental glucose.

2.1 IMPORTANCE OF DIAGNOSIS

As is seen in tests for diabetes, its exact cause has not yet been discovered and studies have led to several hypotheses. However, according to studies by the American Diabetes Association (TOMBINI, 2002) list some hypotheses:

- Hormonal – Kitzmiller; Davidson (2001) define that while the period of pregnancy lasts the placenta produces large amounts of hormones and as progesterone, estrogen and human chorionic somatomamotrophin are essential for fetal development, it has the potential to interfere with the action of insulin in the body maternal, acting as an antagonist of insulin activity, causing an increase in insulin resistance in the last two trimesters of pregnancy;

- Genetics – Tombini (2002) declares gestational diabetes as qualified by insulin resistance analogous to what happens to type 2 diabetes. In this context, women who manifest diabetes during pregnancy are more likely to have type 2 diabetes.

- Obesity – Tombini (2002) this type of diabetes is more common in women in which obesity is part of their lives. Obesity can give off both gestational diabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The Ministry of Health recommended in the Manual of High Risk Pregnancy 2012 the use of clinical risk factors for GDM, combined with fasting blood glucose in early pregnancy (previous 20 weeks ago or as soon as possible), for the investigation of GDM.

The HAPO-2008 study (IADPSG, 2010) uses the 75 g and 2 h oral glucose tolerance test (TOTG-75) between 24-28 weeks without preliminary screening by the risk elements or through the oral tolerance test to glucose of 50 g of 1h (TOTG-50).

The TOTG-50 is intended to be diagnostic and requires a free diet three days before the exam and abnormal rates are fasting 92 mg / dL, 1 hour 180 mg / dL and 2 hours 153 mg / dL. An altered rate is enough for the test to be considered positive. And if fasting is 126mg / dL, diabetes is considered pre-gestational.

The mother’s glucose is transferred to the fetal portion by facilitated dilation and, on occasion, if the mother is hyperglycemic, the fetus, in turn, will also be hyperglycemic. As the pancreas of the fetus is generated and active from the 10th week onwards, a response to this stimulation will occur, with consequent hyperinsulinemia of the fetus.

Insulin, which is an anabolic hormone that, linked to the substrate of hyperglycemic energy, will establish the macrosomia of the fetus together with all its consequences, including the increased risk of stump trauma.

Another disorder of hyperglycemia occurs in the addition of fetal diuresis, leading to polyhydramnios, a disorder that helps premature rupture of membranes and prematurity. Hyperglycemia of the intrauterine womb is linked to the elevation of free oxygen radicals, charged with the greater succession of fetal malformations in this public. After sterilization of the umbilical cord, the neonate slightly metabolizes glucose for excess insulin generation and, as an outcome, presents neonatal hypoglycemia.

One of the main disorders of the fetus in pregnant women with GDM is macrosomia7, which is related to childhood obesity and also to the high risk of metabolic syndrome (MS) in adulthood. Not only macrosomia, but also reduced intrauterine enlargement are involved in the creation of the Metabolic Syndrome and its components.

The elevation of glucose in the bloodstream (hyperinsulinemia) is also included in the generation of pulmonary surfactant, causing a delay in fetal lung maturation and, consequently, an elevated risk of respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) in the neonatal period.

Thus, the increase in the maternal glycemia rate is related to the greater agglomeration of glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c), which in turn, has greater empathy for oxygen and benefits the hypoxia of unequal degrees. Fetal feedback to hypoxia is an increase in the generation of red blood cells, apoliglobulia.

The overabundance or fetal plethora is responsible for the biggest event of neonatal jaundice, renal vein thrombosis and high risk of kernicterus. However, the greatest risks of morbidity and mortality are in these cases and intrauterine death, especially in the last four weeks of pregnancy, is characteristic of poorly contained GDM and more common in fetuses with macrosomia 15,16.

2.2 PHYSIOPATHOLOGY

Diabetes Mellitus (DM) represents a cluster of metabolic disorders identified by hyperglycemia resulting from insulin irregularity. Such irregularity may be due to decreased pancreatic generation or undue release and / or peripheral insulin resistance (8, 9, 13).

The designation of the etiopathogenesis of dysglycemia benefits the understanding of the pathophysiology and offers the basis for a certain management of each case in the different stages of the individuals’ lives. The period of pregnancy is characterized by the state of insulin resistance. This situation, associated with the marked change in glycemia control devices in relation to the applicability of glucose expenditure by the embryo and fetus, may contribute to the occurrence of changes in glycemia favoring the development of GDM.

Hormones such as cortisol, placental lactogen, prolactin generated by the placenta and others that are elevated due to the gestational period, can stimulate a decrease in the action of insulin in its receptors and, finally, an increase in insulin generation in healthy pregnant women.

Such a mechanism, however, has a chance not to be seen in pregnant women who already have their insulin generation power at the limit. This occurs in women who have little increase in insulin generation and, thus, may have diabetes during pregnancy.

The current guidelines of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the fundamental regulations for the management of DM advise that the increase in the blood sugar rate, the hyperglycemia first detected at any moment of pregnancy should be classified and characterized in GDM or DM diagnosed in gestation of English Overt Diabetes (8, 9, 14, 15). It is divided into two broad categories:

- Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM): found for the first time in the period of pregnancy, with blood glycemic rates that do not complete the diagnostic specifications for DM.

- Diabetes Mellitus found in pregnancy (Overt Diabetes): without previous diagnosis of DM, with hyperglycemia detected in pregnancy and with blood glycemic rates that reach the WHO specifications for DM in the absence of pregnancy.

The pathophysiological manifestations of GDM are associated with metabolic adjustments caused during pregnancy. Bertini (2001) defines it as the continuous need to ingest glucose and important amino acids for the fetus, adding the demands for fatty acids and cholesterol and hormonal changes, essentially those defined by glucagon, glucocorticoids, estrogens, progesterone and chorionic somatotropin.

According to Kitzmiller and Davidson (2001) in the first trimester of pregnancy, changes stimulated by placental hormones such as human karyonic gonadotropin (hCG) have a rare direct consequence on carbohydrate metabolism.

Drawing a comparison with the development of the placenta, there is a gradual increase in the generation of hormones that antagonize the action of insulin, such as progesterone, estrogen and especially human chorionic somatotrophin. Thus, in the second and third trimester of pregnancy, an increase in insulin resistance is visible, reflecting an increase in insulin accumulation.

We identified a demand for insulin production greater than the capacity of pancreatic cells to produce insulin, with the onset of gestational diabetes mellitus. Thus, two different stages are observed in pregnancy, an anabolic and a catabolic phase, the first is evidenced by a reduction in blood glucose due to higher glucose storage, while the second is due to a reduction in blood glucose due to greater consumption of the fetus, (SANKOVSKI , 1999). At that moment, metabolic conditions are identified in the normal pregnant woman characterized by a fasting threshold state.

Bertini (2001) also establishes as an elongated maternal fasting condition that leads to an unrestrained metabolic state of starvation, coercing the organism to use energy, specifically the hydrolysis of triglycerides in adipose tissue. Forcing the investigation of new sources of glucose that ends up generating new reactions that elevate ketone bodies and free fatty acids.

2.3 SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Gestational diabetes, like other types of diabetes, can offer disorders, both in the short term and in the long term. Pregnant women with GDM are rated as risky pregnant women, as outrage constitutes high rates of morbidity, in addition to providing greater opportunities for glucose intolerance, which may cause more risks of having DM2 after pregnancy.

Hormonal changes in early pregnancy cause vomiting and nausea in many women and in diabetics with autonomic neuropathy or gastroparesis, hypermeresis can be destructive (KITZMILLER; DAVIDSON, 2001).

The risks and disorders are still not well elucidated, for this reason, in recent years, several investigations have been carried out on this topic, including addressing the new methods of diagnosis of GDM, which faced modifications from 2005 to the present day (FERRARA, 2007 ; SBD, 2014-2015).

Often, the diagnosis of GDM is made through active investigation, with tests that stimulate an excessive glucose load, in the second trimester of pregnancy. However, nowadays, the suggestion is to carry out the early selection of GDM in pregnant women, right at the first prenatal consultation, thus making it possible to identify preexisting DM cases, which are unlikely to be considered GDM (SMCD, 2010 apud WEINERT, 2011; IADPSG CONSENSUS PANEL, 2010).

In their analysis, Simon, Marques and Farhat (2013), assert that to date, there are many conflicts about the cut-off point for fasting blood glucose in the investigation of GDM, and that this reference varies according to the researched public and the cutoff point used. These authors declare that no occurrences of GDM were found in patients who manifested fasting glucose lower than 90mg / dL in the first trimester or who did not have a risk factor or risk factors.

For this reason, the SBD suggests that the new international requirements for investigating and diagnosing GDM be used, because, even though they express deficiencies, they are the only ones that legitimately demonstrated by study the combination of the mother’s blood glucose rates and its consequences in the newborn health (SBD, 2014-2015), in addition to helping to verify high-risk pregnancies, in which adverse results can be avoided and your interference is plausibly simple (COUSTAN, 2012).

Therefore, the new diagnostic criteria for GDM adopted by the American Diabetes Association (ADA), offered by the National Diabetes Data Group (IADPSG), another by the World Health Organization and also by the Brazilian Society of Endocrinology and Metabology. The Association recommends monitoring pregnant women up to 25 years of age and between the 24th and 28th weeks of gestation, using the glycemic index of 1 hour after ingesting 50 g of dextrosol (SULLIVAN and MAHAN apud and NOGUEIRA, 2001).

There are discussions between the new items for diagnoses and the old item, where the cut-off point was 85mg / dL, because in their research, 13% of the patients needed additional insulin administration to control their blood glucose, which have not yet been diagnosed by these new IADPSG requirements, which makes them believe that the new fundamentals may interfere in the incorrect treatment of some pregnant women (SIMON; MARQUES; FARHAT, 2013; SACKS et al, 2012).

Queiros, Magalhães and Medina (2006) also ratify that the screening test be carried out between the 24th and 28th weeks of gestation. If it is negative, it should be repeated after the 32nd week. Pregnant women who, perhaps, express a high risk for the pathology should preferably take the test soon after the pregnancy is revealed.

If the fasting glycemic index is greater than or equal to 126 mg / dL, this woman is already diagnosed with GDM, since this value already qualifies, on its own, Diabetes Mellitus (QUEIROS; MAGALHÃES; MEDINA, 2006; SBD, 2014 -2015). The Brazilian Diabetes Society recommends that the fasting glycemic rate should be requested at the first prenatal visit, and, if it is less than 92 mg / dL, the fasting glycemic rate test should be requested again in the second trimester of pregnancy . (SBD 2014-2015).

Having a negative outcome, they continue with the same criteria for the other pregnant women. In all cases of pregnant women, the Oral Glucose Tolerance Test (PTOG) must be performed, with 100g of glucose for GDM certification, with an elaboration of fasting between 10 and 14 hours and the collection should be done in the morning, at rest. (QUEIROS; MAGALHÃES; MEDINA, 2006).

After two weeks of diet, if blood glucose levels remain altered, with a fasting value greater than or equal to 95 mg / dL and 1 hour postprandial equal to or greater than 140 mg / dL, or two hours postprandial are found if greater than or equal to 120 mg / dL, it is essential to start pharmacological treatment.

3. PRECAUTIONS AND POSSIBLE TREATMENT

Taking into account the possible disorders of the GDM, for the mother, as well as for the baby, the relevance of arguing more about the subject is glimpsed, substantially due to the change in the patterns of GDM diagnosis that occurred in 2005 and which are found present to the present day.

It is essential that the patient be examined to determine whether she has returned to a state of normal carbohydrate tolerance and whether pregnancy was the metabolic marker of diabetes. Examining the literature, it was possible to glimpse the relevance of diet, physical activity and glycemic control in the treatment, since the facts about pharmacological treatment are still unsatisfactory and questionable.

When it comes to drug treatment, according to Pontes et al. (2010), metformin hydrochloride was identified as the most convenient medication for pregnant women with GDM, however, even today, there are few literature that reaffirm its safety and efficacy, even if its results associated with fetus macrosomia, birth weight, admission to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, hypoglycemia rate of the newborn, among other disorders, are questionable.

Pregnancy requires certain nutritional demands that require substitutions in the diet. Adequate dietary treatment for a pregnant woman should provide satisfactory nutrition for the pregnant woman and the fetus, aiming at an almost euglycemia (BERTINI, 2001).

Although exercise is not proven to be beneficial in women with GDM, the change in lifestyle can last long after delivery and help prevent the onset of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its extemporaneous disorders (CEYSENS et al., 2007) .

The review by BRODY et al. (2003) points out that a percentage of more than 70% of women with GDM develop mild hyperglycemia and their treatment is only with diet. The aid of intensive treatment in these women is still uncertain, but in women with high hyperglycemia, treatment with insulin administration decreases the occurrence of macrosomia. Only a percentage of 30% of pregnant women with GDM use insulin as a form of treatment.

According to the Brazilian Diabetes Society (2014-2015), as soon as the GDM is detected, non-pharmacological treatment begins, which is based on dietary guidance and physical activity practices, as long as obstetric contraindications are taken into account. Dietary guidance aims at metabolic control and massive weight gain, with gain of 300 to 400 g per week tolerated, starting in the second trimester of pregnancy.

The diet for women with GDM needs to comprise six to seven meals a day, with three main meals, about two to three snacks and one before bedtime. She needs to offer enough calories and nutrients for the needs of the pregnancy, as well as achieving the goals of the blood glucose levels preliminarily established so that cases of hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia or ketosis are dispensed with. (QUEIROS; MAGALHÃES; MEDINA, 2006).

The weight increase varies according to the BMI of each pregnant woman. For women with a BMI greater than 19.8 kg / m², the average weight increase is between 12.5 to 18 kg; BMI between 19.8 and 26 kg / m², average elevation from 11 to 16 kg; BMI between 26.1 to 29 kg / m², average elevation from 7 to 11 kg; BMI elevation of 29 kg / m², elevation of less than 6 kg (QUEIROS; MAGALHÃES; MEDINA, 2006).

The practice of physical exercises aims to reduce glucose intolerance by means of cardiovascular restriction that produces increased affinity and binding of insulin to its receptor through the reduction of intra-abdominal fat, elevation of insulin-sensitive glucose transporters in muscle, increased blood flow in tissues sensitive to insulin and reduced levels of free fatty acids.

The major concern is the safety of the pregnancy for the mother and the fetus, the most important criteria to be evaluated during sports practice is the maternal-fetal well-being, such as: heart rate and fetal heart rate, blood pressure, temperature and uterine-maternal dynamics.

Various types of equipment and physical activities have been prescribed for pregnant women with GDM, such as: vertical exercise bike, rowing, horizontal exercise bike (with backrest) and ergometer for upper limbs.

In general, insulin is only introduced as a medicine when diet and exercise have failed to achieve adequate metabolic control. Insulin was used alone and was initially prescribed in cases of diabetes. Among the different types of insulin available today we have the short-acting (lispro and regular) and the long-acting insulin.

Weinertet et al. (2011) indicates glibenclamide as the drug of choice among sulfonylureas for pregnant women, identified as safe and effective starting in the second trimester of pregnancy. Silva et al. (2007), in their analyzes, concluded that the class of pregnant women who exhibited the greatest results with the administration of glibenclamide were those with a gestation period of more than 19 weeks and weight gain of up to 9 kg, in addition to not being noticed infants, a situation that reinforces the security of their administration.

However, there is a disagreement regarding the safety of glibenclamide, when they declare that it is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and further research on this drug is needed. In research with animals, the drugs acarbose, glibenclamide and insulin are named as class B for use during pregnancy, that is, they did not exhibit harmful fetal effects, and there is no scientific research that confirms the harmful effects of these drugs on humans (LARIMORE; PETRIE , 2000; apud SILVA et al., 2005).

The recommended insulin doses are administered according to the glycemic control of the pregnant woman, raising the regular insulin when the NPH insulin occurs, taking into account fasting and pre-meal blood glucose.

Insulin therapy treatment for GDM is adopted when glycemic control is not effective, insulin administration is recommended, with a combination of diet and exercise. However, there is no standard guidance protocol regarding different dosages for different stages of pregnancy, as they change according to weight variation (BASSO et al., 2007).

According to Detschet al (2012), the primary reason for insulin administration was the junction between previous GDM and causes of risk, such as family history of DM in first-degree relatives. The main causes of risk for GDM are: identification of late GDM, age over 30 years, polyhydramnios, excessive fetal growth, identification of late GDM, delayed start of prenatal care, fetal malformations and death of the fetus or stillbirths , obesity or overweight, short stature, accumulation of abdominal adiposity, low family income, obstetric history of repeated abortions, fetal overgrowth, polycystic ovary, fetal overgrowth, macrosomia, arterial hypertension or pre-eclampsia in current pregnancy ( COSTA et al., 2015; SBD 2014-2015; DETSCH et al., 2012).

4. CONCLUSIONS

The great impact of the discovery of insulin, the immense knowledge of the device of fetal involvement by hyperglycemia and the therapeutic criteria in gestational diabetes mellitus are of undoubted relevance. As a result, the strong demand for optional and accessible mechanisms for the entire population is of paramount importance and should be valued.

In summary, GDM is a condition that affects women during pregnancy. During pregnancy, predisposed pregnant women may develop complications in the metabolism, which may result in gestational diabetes mellitus and its prevalence varies from 3% to 13% of the total number of pregnant women, varying according to the population analyzed and the criterion used. (SBD, 2014-2015).

Thus, GDM came to be considered as a public health torment, and even when there is a well-attended prenatal, some problems such as the growth of the fetus and other imbalances can persist. In this way, the pregnant woman will need to have a good prenatal and will become aware and be aware of the diagnoses and pathophysiology, as well as the treatment and possible complications and risks that the fetus may run. Such care is of paramount importance for a safe and trouble-free pregnancy for mom and baby.

In this understanding, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that a good monitoring of GDM contains diet, satisfactory metabolic control, physical exercises and medication, in addition to the prenatal care performed by a specialized multidisciplinary team (WHO, 2013).

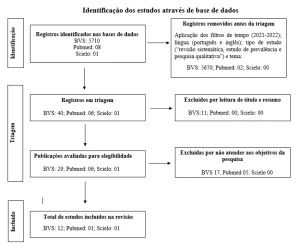

This study aimed to argue and ponder the GDM with an overview of care, possible interventions, and complications during pregnancy. Thus, the study had a descriptive and exploratory methodology of bibliographic review, using the following descriptors for this purpose: GDM, Risk Factors, Care. The research covered the period from 2005 to 2018, as it addresses the most recent scientific literature on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus.

5. REFERENCES

ACM. Manual de pesquisa das Diretrizes do ACSM para testes de esforço e sua prescrição. 4ª edição Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan, 2003, p.280-283.

American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2011 Jan; 34 Suppl 1:S62-9. 2. IDF Clinical Guidelines Task Force. Global Guideline on Pregnancy and Diabetes. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation, 2009.

American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2010 Jan; 33 Suppl 1: S62-9. 47.

BASSO N. A. S. Et al. Insulinoterapia, controle glicêmico materno e prognóstico – perinatal – diferença entre o diabetes gestacional e o clínico. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia. Rio de Janeiro, v. 5, p.254-259, 2007.

BERTINI, A. M. Diabetes mellitus. In: GUARIENTO, A. MAMEDE, J. A. V. Medicina materno-fetal. São Paulo: Atheneu, 2001.

BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Ações Programáticas Estratégicas. Gestação de alto risco: manual técnico / Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde, Departamento de Ações Programáticas Estratégicas. 5ª ed. Brasília: Editora do Ministério da Saúde, 2010. p 302.

BRODY SC, Harris R., Lohr K. Screening for gestational diabetes: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 101:380-92.

CEYSSENS P.J., Mesyanzhinov V., Sykilinda N., Briers Y., Roucourt B., Lavigne R., Robben J., Domashin A., Miroshnikov K., Volckaert G., Hertveldt K. The genome and structural proteome of YuA, a new Pseudomonas aeruginosa phage resembling M6. J. Bacteriol. 2008; 190:1429–1435

COSTA R. C. Et al. Diabetes Gestacional assistida: perfil e conhecimento das gestantes. Revista Saúde (Santa Maria), v. 41, n. 1, p. 131 – 140, 2015.

COUSTAN D. R.The American Diabetes Association and the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups Recommendations for Diagnosing Gestational Diabetes Should Be Used Worldwide. ClinicalChemistry. V. 58, n. 7, p. 1094-1097, 2012.

DETSCH J. C. M. et al. Marcadores para o diagnóstico e tratamento de 924 gestações com diabetes melito gestacional. Arquivos Brasileiros de Endocrinologia e Metabolismo. São Paulo, v. 55, n. 6,2011.

FERRARA A. Increasing prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus: a public health perspective. Diabetes Care. 2007; 30, Suppl 2:S141-6.

IDF Diabetes Atlas. Seventh Edition ed. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation; 2015. Disponível em: http://www.diabetesatlas.org 2. Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde 2013: percepção do estado de saúde, estilos de vida e doenças crônicas. Brasília: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística; 2014. Disponível em: ftp://ftp.ibge.gov.br/ PNS/2013/pns2013.pdf 3.

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Disponível em: http://ibge.gov.br/home/presidencia/noticias/noticia_visualiza. php?id_noticia=1699&id_ pagina=1. Acessado em 28/junho/2019.

KITZMILLE, J. L.; DAVIDSON, M. B. Diabetes e gravidez. In: DAVIDSON, M. B. Diabetes Mellitus: diagnóstico e tratamento. Rio de Janeiro: Revinterr, 2001. P. 277-303.

NOGUEIRA, A. I. Diabetes mellitus e gravidez. Rio de Janeiro: MEDSI, 2001. P. 465-568-644.

O’SULLIVAN JB, Mahan CM. Criteria for the Oral Glucose Tolerance Test in Pregnancy. Diabetes. 1964; 13:278-85. 18.

OMS. Obesidade Prevenindo e Controlando a Epidemia Global. 1ª ed. São Paulo: Roca; 2004. p. 256. 36. Bolognani CV, Souza SS, Dias A, Rudge MVC, Calderon IMP. Circunferência da cintura na predição do diabetes mellitus gestacional. 2011 [em publicação].

ORGANIZAÇÃO PAN-AMERICANA DA SAÚDE 20. Carpenter MW, Coustan DR. Criteria for screening tests for gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982; 1; 144(7):768-73. 21. Proceedings of the Third International Workshop-Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus; 1990 November 8-10; Chicago, Illinois; 1990.

QUEIROS J, MAGALHÃES A., MEDINA J. L. Diabetes gestacional: uma doença, duas gerações, vários problemas. Revista Brasileira de Endocrinologia, Diabetes e Metabolismo, v. 1, n. 2, p. 19-24, 2006.

SANCOVSKI, M. Diabetes e gravidez. Terapêutica em diabetes. Centro BD de educação em diabetes. V. 5, n. 25, p. 1-5, 1999.

SILVA J. C.et al. Resultados preliminares do uso de anti-hiperglicemiantes orais no diabete Melito gestacional. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia. V. 27, n.8, p. 461-466, 2005.

SILVA J. C.et al. Tratamento do diabetes mellitus gestacional com glibenclamida – fatores de sucesso e resultados perinatais. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia. Rio de Janeiro. V. 29, n. 11, p. 555-560, 2007.

SIMON C. Y., MARQUES M. C. C., FARHAT H. L. Glicemia de jejum do primeiro trimestre e fatores de risco de gestantes com diagnostico de Diabetes Melito gestacional. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia. V. 35, n. 11, 2013.

SOCIEDADE BRASILEIRA DE DIABETES. DIABETES MELLITUS GESTACIONAL: DIAGNÓSTICO, TRATAMENTO E ACOMPANHAMENTO PÓS-GESTAÇÃO. In: Diretrizes da Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes: 2014- 2015/Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes; [organização Jose Egidio Paulo de Oliveira, SergioVencio]. – São Paulo: AC Farmacêutica, 2015.

TOMBINI, M. Guia completo sobre Diabetes da American Diabetes Association. Rio de Janeiro: Anima, 2002. p. 44-45-340-341.

WEINERT LS et al. Diabetes gestacional: um algoritmo de tratamento multidisciplinar. Arquivos Brasileiros de Endocrinologia Metabólica. V. 55, n. 7, p. 435-445, 2011.

WHO expert Committe on Diabetes Mellitus Technical Report: World Health Organization 1964. Report No.: 310. 19. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and other categories of glucose intolerance. National Diabetes Data Group. Diabetes. 1979; 28(12): 1039-57.

[1] Student of the Higher Pharmacy Course.

[2] Advisor. Specialization in Professional and Technological Education. Graduation in Pharmacy. Graduation in Sciences / Mathematics.

Submitted: May, 2020.

Approved: November, 2020.