ORIGINAL ARTICLE

SANTOS, Isadora Alice Fachini dos [1], SILVA, Franklin Barbosa da [2], AGUIAR, Felipe Muniz [3], PINHEIRO, Tiago Novaes [4], BRAGA, Francisco Pantoja [5]

SANTOS, Isadora Alice Fachini dos. Et al. Bucomaxillofacial prosthesis procedures after surgical treatment of neoplasia: Case report. Multidisciplinary Core scientific journal of knowledge. Year 05, Ed. 07, Vol. 01, pp. 87-111. July 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/odontologia/protese-bucomaxilofacial, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/odontologia/protese-bucomaxillofacial

SUMMARY

In the face of malignant head and neck neoformations, mucoepidermoid carcinoma is one of the manifestations of great occurrence, with the palate region being the most involved. The treatment may result in mutilation in the oral cavity, causing bucosinusal communication, which can be restored through obturator prostheses. The aim of this study is to report a clinical case of the manufacture of a hollow palatine obturator prosthesis in a patient with mucoepidermoid carcinoma after partial maxilectomy, and the facial molding technique prior to surgical treatment of recurrence. The patient sought dental care, mentioning presenting his total obturator prosthesis poorly adapted due to the time of use. His treatment plan consisted of the manufacture of the obturator prosthesis by the cloning technique and conventional removable partial prosthesis. After a few months, recurrence of the lesion was clinically detected, where a new surgical procedure was performed, which was not successful. Then we opted for another approach, developing facial molding, because a more invasive surgery would be necessary, which could have consequences on the face. The patient was undergoing radiotherapy treatment, and the new medical intervention was chosen. The obturator prosthesis is an effective alternative in the rehabilitation of patients undergoing surgical resections, which resulted in mutilations. Thus, the choice of cloning technique with some modifications, in this case in addition to the cost-benefit, the clinical and laboratory stages were reduced and as a consequence the replacement of the prosthesis was faster effective. In addition, the role of this rehabilitation in the reintegration of the individual into the biopsychosocial environment, the restoration of function, aesthetics and comfort, is of great relevance.

Keywords: Mucoepidermoid carcinoma, palatine shutters, maxillofacial prosthesis, removable partial prosthesis.

1. INTRODUCTION

Malignant head and neck neoformations constitute about 5% of all existing tumors, it is largely denoted by squamous cell carcinoma also called epidermoid or squamous cell carcinoma, being among the most recurrent cancerous diseases in Brazil (RETTIG and D’SOUZA, 2015). Studies show a higher predominance in underdeveloped countries, with men being more affected than women in a ratio of 2:1 between the fourth and seventh decades of life. The main threats to the progress of this type of oral cancer are the consumption of tobacco and alcohol combined, low socioeconomic and educational level (REZENDE, 1997; SOUSA et al., 2016).

The distinction of treatment in malignant head and neck diseases can be performed through surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy or combination therapy. The therapy in the preliminary phase through surgery or radiotherapy, will result from the patient’s preference, comfort, cost, location and mastery of the disease. Radiotherapy, even revealing satisfactory results, may leave sequelae in the skin, mucosa, salivary glands and tooth (ARTOPOULOU et al., 2017). And chemotherapy in many episodes is applied as a palliative alternative or in combination therapy. Thus, surgery is still the prevalent treatment, whose purpose is integral surgical removal with free margins reducing the morbidity of diseases (CAMPANA e GOIATO, 2013; REZENDE, 1997).

When there are occurrences of maxillary tumor, maxillary excision will be performed, with total or partial maxilectomy, directly afflicting the functionality of the maxilla (GASTALDI et al., 2017), which plays its role in phonation, chewing and swallowing (CAMPANA e GOIATO, 2013). With regard to this, the performance of this type of treatment will promote functional deformities in the oral cavity causing buco-sinus communication, which can be restored through obturator prostheses, abstaining from anasalad speech and fluid leakage inside the nasal cavity (BADADARE et al., 2014).

The obturator prostheses are classified according to the area of operation and can be divided into: internal reparative prosthesis (tutor of the periosteum and restorative of the facial skeleton); immediate external (prophylactic of scar retraction, tutorof the periosteum) and late (healing and restorative broker) (REZENDE, 1997). The preparation of palatine obturator prosthesis is paramount in the restructuring of imperfections resulting from total or partial maxilectomy. For each maxillary deformation has a possibility of elaboration of a palatine shutter, if it is of great thickness, the stability of the prosthesis may be impaired. A very significant factor is the weight of the prosthesis and Recommend the production of the hollow shutter, which enables the patient’s well-being (LIKHTEROV et al., 2017). In addition to defects in the oral cavity, surgical resections can affect deformations in the face, and it is essential to perform facial molding for further planning, in which the facial model is the reproduction of the patient’s face for subsequent prosthetic rehabilitation (AQUINO et al., 2012).

The aim of this study is to report a clinical case of the manufacture of a hollow palatine obturator prosthesis in a patient with mucoepidermoid carcinoma after partial maxilectomy, and the facial molding technique prior to the invasive surgical procedure.

2. CASE REPORT

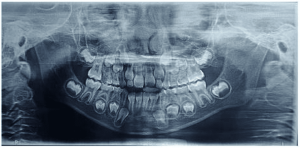

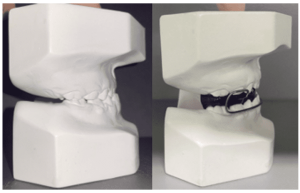

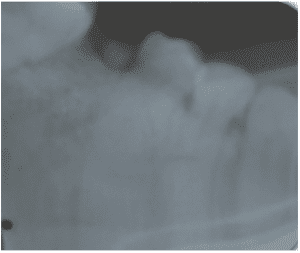

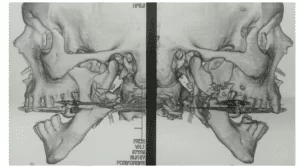

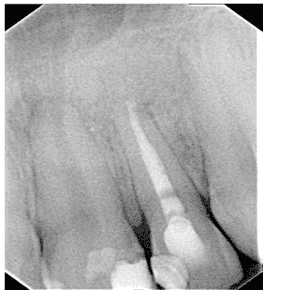

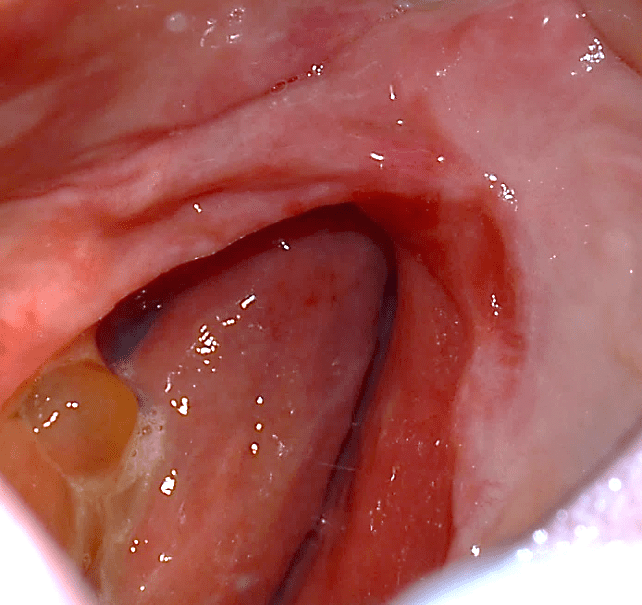

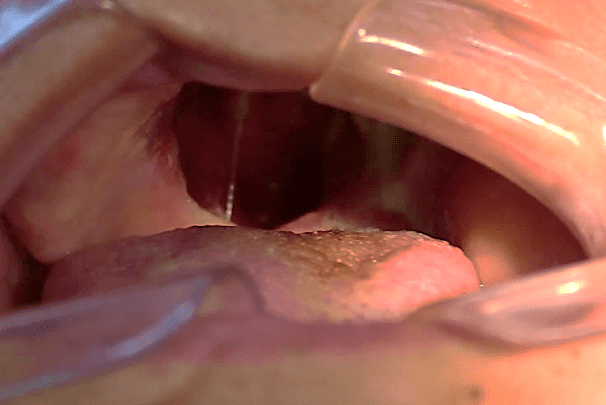

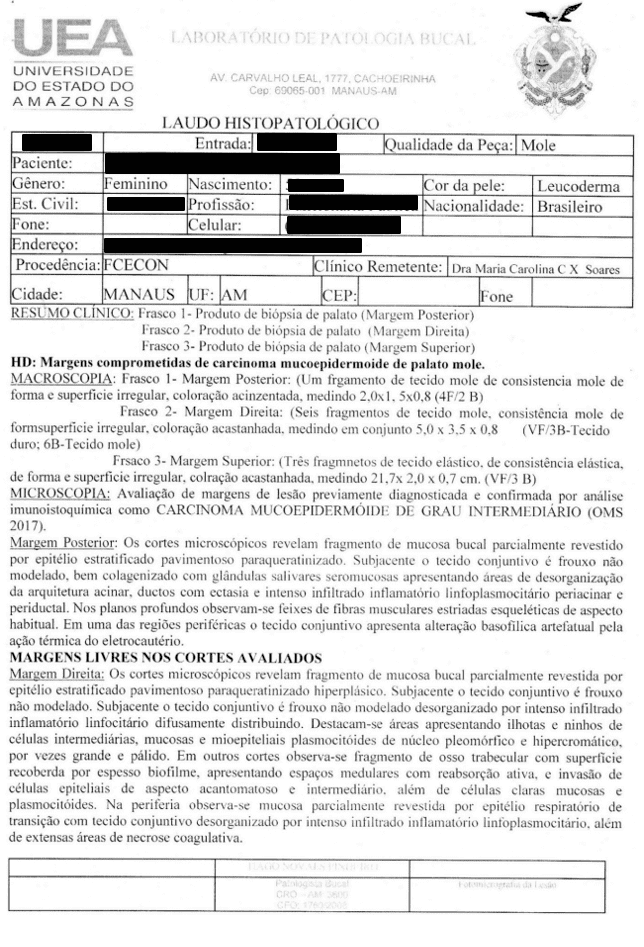

A 49-year-old female patient attended the prosthesis clinic at Nilton Lins University, mentioning dissatisfaction with her total obturator prosthesis, because she had a “broken front tooth” and the prosthesis was “falling”, emphasizing the desire to maintain the shape of the same. In the anamnesis reported that previously in 2012 he was diagnosed with mucoepidermoid carcinoma of intermediate degree in the palate (Appendix 1) and in 2013 after performing surgical removal and performing new tests, who did not indicate the presence of malignancy (Appendix 2), was attested as cured, besides being hypertensive and using the drugs losartan potassium 50 mg twice daily and levanlodipine besidate 2.5 mg once a day. No alterations were observed on extraoral clinical examination. In the intraoral clinical examination, there was absence of the upper arch teeth, bucosinusal communication and partial maxillary edge and in the lower region only the presence of teeth 31, 32, 33, 41, 42, 43, 44 and 45 (figures 1 and 2).

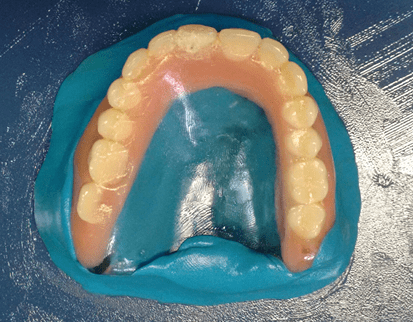

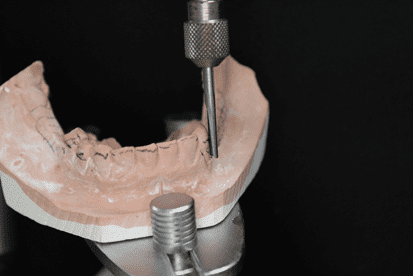

The treatment plan consisted of performing a total superior prosthesis obturator by the cloning technique and the preparation of a conventional removable partial prosthesis (PPR). Cloning of the total superior obturator prosthesis began with the application of solid vaseline on the bench and in the old prosthesis, the condensation silicone (Clonage®, Nova DFL, Brazil) was manipulated to model the inner part of the prosthesis, covering a portion of the outer edge, leaving it expulsive (figure 3).

Figure 1: Surgical defect of the upper arch.

Figure 2: Initial aspect of the patient in occlusion.

Figure 3: Mold making.

Then, a thin layer of solid vaseline was inserted into the base already modeled and the cover and copy of the teeth were made (figures 4 and 5). Soon after, a base of the prosthesis was elaborated with acrylic resin (Duralay®, Reliance, USA) by the brush technique introducing the resin in small proportions, because this type of material has less polymerization contraction (figure 6). Then, perforations were made in the posterior region of each side of the cover, in order to fill the mold with wax 7 (figure 7). Where initially the wax was heated to boiling and with the aid of a glass dripper the increments were added by filling the mold completely (figure 8). And, after cooling the wax, the base cover silicone was removed, thus obtaining the properly mentioned cloning of the old prosthesis (figure 9).

Figure 4: Internal mold.

Figure 5: External mold.

Figure 6: Increase of self-curing acrylic resin.

Figure 7: Perforations in the posterior region.

Figure 8: Wax increments 7 added.

Figure 9: Clone of the total obturator prosthesis.

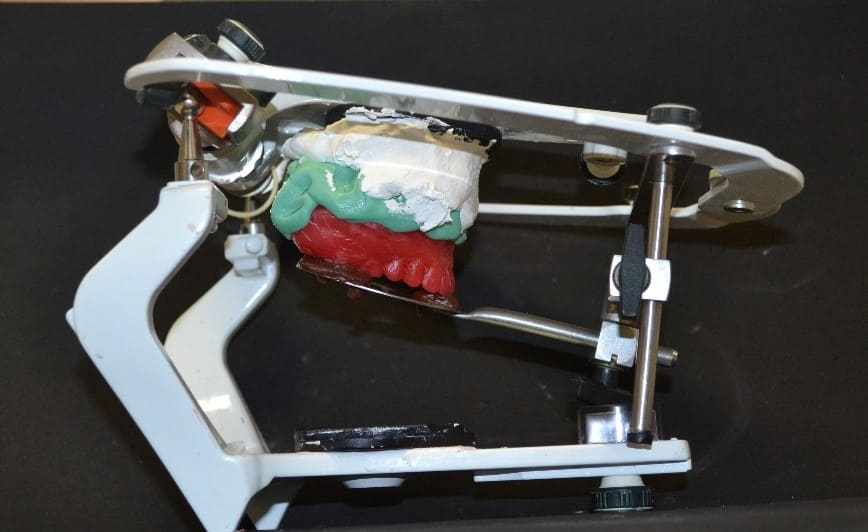

The clone was taken in the mouth to check the adaptation, with no need for adjustments. The assembly was then performed on the semi-adjustable articulator (ASA) (Bio-Art 4000-S, Brazil), for this it was heated to the stick godiva, which was inserted in the fork perforations, subsequent heating was performed and the fork carried in the mouth with the clone for the recording of the molar straps and incisal edges of the anterior teeth. Then, the facial arch was mounted by adjusting the fixation screws (figure 10). After obtaining the records, the base was made with heavy condensation silicone (Zetaplus®, Zhermack, Italy) and the upper orientation plane was mounted on the ASA (figure 11).

Figure 10: Facial arch assembly.

Figure 11: Top model mounted on the ASA.

Subsequently, the anatomical molding of the lower arch was produced with alginate (Jeltrate dustless®, Dentsply, Argentina) (figure 12) and succeeded by the preparation of the study model in type IV plaster (Durone®, Dentsply, Argentina) and design (figure 13). In the latter, the circumferential clamps were chosen in teeth 44 and 45, and, t-staple in tooth 33, the lingual bar was selected as the larger connector. After this, mouth II was prepared, the niches were made and the molding of work with condensation silicone (Zetaplus®, Zhermack, Italy) (figure 14), which was sent to the laboratory for the purpose of casting the metal frame. After adapting to the model, the orientation plan with pink 7 wax was developed, making the necessary adjustments.

Figure 12: Anatomical mold of the lower arch.

Figure 13: Design.

Figure 14: Working molding of the lower arch.

Then, as the clone was used in the upper arch, there was no need to make adjustments, so the vertical dimension was determined and recorded in the centric relationship position. Then, the orientation plans were fixed with the aid of heated paper clamps (figure 15), and taken to the ASA to fix the lower model. Finally, the set was forwarded to the laboratory to assemble the teeth, with it being completed, and the test was performed, in which it was found that no adjustments in the position of the stock teeth were necessary (figure 16). The next step consisted of the peripheral seal with godiva baton, which was possible to obtain the anatomical details of the desired plateable area and retention (figure 17).

Figure 15: Clamps fixed bilaterally.

Figure 16: Proof of the assembly of teeth.

Figure 17: Peripheral sealing finished.

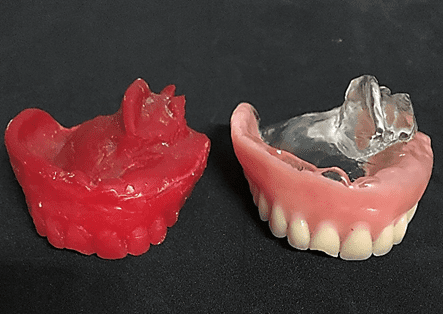

Continuing, the last molding of the clone’s test base with fluid condensation silicone (Oranwash L®, Zhermack, Italy) (figures 18 and 19) was made, and the patient remained with the teeth in occlusion for molding (closed mouth technique). The test bases and molding were forwarded to acrilization.

After acrilization of the obturator prosthesis, it was installed in order to verify the necessary adjustments still with the PPR test base, with no need for adjustments (figure 20). The PPR was sent for acrylization and at the end the prostheses were installed checking the adjustments again, verifying favorable adaptation, reestablishing comfort, function and aesthetics for the patient (figure 21).

Figure 18: Molding performed with the closed-mouth technique.

Figure 19: Side view of functional molding.

Figure 20: Proof of the obturator prosthesis after acryllization based on the PPR test.

Figure 21: Final aspect.

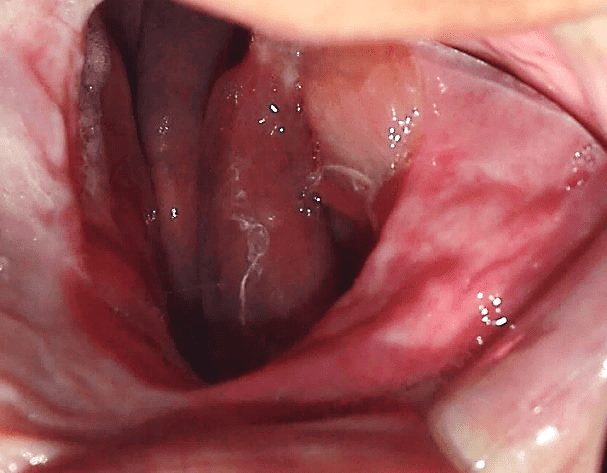

After three months using the obturator prosthesis, new control tests were performed, and immediate surgical intervention was necessary, because the neoplastic lesion had recurs (figure 22). On the patient’s return, after the first surgery (figure 23) and with the result of the histopathological examination (Appendix 3), which indicated margin involvement. The medical team intervened and elaborated another treatment plan, which consisted of surgical removal with margin enlargement. In a new dental visit, twelve days after the second surgery (figure 24), the histopathological examination again indicated compromised margins (Appendix 4). Therefore, a more invasive surgery was planned by the medical team, which may lead to facial involvement.

Figure 22: Recurrence of the lesion.

Figure 23: Surgical step 1 of removal.

Figure 24: Surgical step 2 of removal.

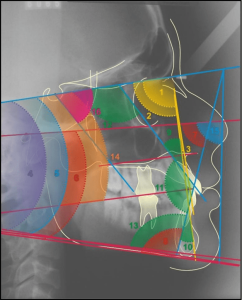

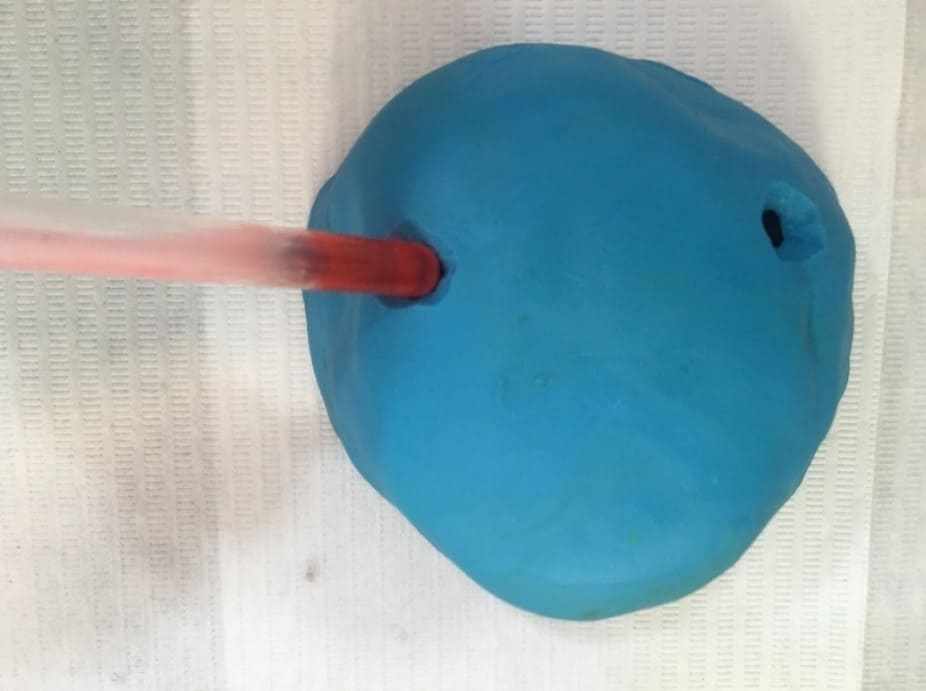

Thus, a new planning for rehabilitation was executed, having as a starting point the facial molding. The clinical sequence used was: skin cleansing by removing makeup and oiliness, protection of hair with bandage, application of solid vaseline in the facial hairs, tamponade of the nostols with cotton wool and a canudo for mouth breathing (figure 25). Then, the alginate (Jeltrate Dustless®, Dentsply, Argentina) was started using two parts, with the proportion of water/powder being 4:4. After being manipulated, it was deposited in small parts in the region to be molded with the aid of a spatula (figure 26), then the retention with cotton on the alginate was performed and the common plaster type II (Asfer®, Brazil) was added, in order to confer stiffness (figure 27), preventing deformation during its removal.

Figure 25: Preparation for the beginning of facial molding.

Figure 26: Alginate deposition on the face.

Figure 27: Insertion of plaster on the retention.

The mold was removed with slight movements, prompting the patient to move the mime muscles (figure 28). Immediately after molding, the mold was filled with type IV plaster (Durone®, Dentsply, Argentina) to obtain the facial model. With the aid of a vibrator, the plaster was deposited on the mold to prevent the formation of bubbles and when taking prey, the model was removed, so the finishes were executed (figure 29). Subsequent surgical removals, the treatment plan of choice was radiotherapy, being performed for two months, where it has already begun and is under medical follow-up.

Figure 28: Mold removed.

Figure 29: Model of the finished face.

3. Discussion

Malignant neoplasms of salivary glands are slightly recurrent (DE SOUSA BARBOSA et al., 2005). According to studies by Santos et al. (2003) which showed that such neoplasms represent about 2% to 6.5% of tumors in the head and neck region. Regarding these neoformations, mucoepidermoid carcinoma is the most common type (GIOVANINI et a., 2007), representing about 5% of all salivary gland tumors (SOUSA et al., 2016). Some authors state that there is a predilection for more affecting the female sex, on the other hand, some studies point to an egalitarian distribution of sex (FRANÇA et al., 2008; SOUSA et al., 2016), manifesting between the 2nd and 8th decades of life with an average age of 45 years (REZENDE, 1997). With regard to the smaller salivary glands, the palate is the most affected region (GIOVANINI et al., 2007; HYAM et al., 2004). In the case reported, even though the patient did not present any predisposition related to her life habits, she was affected by mucoepidermoid carcinoma of intermediate degree in the palate region, and, at first after treatment and confirmed by examinations, was considered cured. However, a few years later there was recurrence of the lesion, and according to studies, it is reported that mucoepidermoid carcinoma of intermediate and high degree have recurrence rate in 42% in the period of 10 years (KROLLS et al., 1972).

It has been reported in the literature that the forms of mucoepidermoid carcinoma treatments depend on the degree of differentiation, presence or not of metastases and their staging (GIOVANINI et al., 2007; REZENDE, 1997). Therefore, according to Guzzo et al. (2010), radiotherapy is considered an adjunct therapy in these cases and recommended in situations of metastasis, high histological degree and compromised surgical margins, and in inoperable circumstances, is the first line of treatment. Unfavorable circumstances such as xerostomia, mucositis, candidosis and osteradionecrosis may occur. In contrast, studies by Ozawa et al. (2008) denote that patients with mucoepidermoid carcinoma, in which they underwent adjuvant radiotherapy, had worse survival when compared to patients who were operated only. Another therapy found is chemotherapy, which represents a palliative treatment in high-grade cases, but no studies have been defined (ADELSTEIN et al., 2012).

Thus, the first choice for the treatment of mucoepidermoid carcinoma is surgical resection with margins (BRANDWEIN et al., 2001). In situations of low and intermediate degree of malignancy, surgical treatment is indicated (GIOVANINI et al., 2007). However, this method of treatment may result in temporary or definitive mutilations (GUZZO et al., 2010). In the present case, we opted for the surgical procedure, performing hemimaxiectomy as the first intervention, and, after recurrence, total maxilectomy. Despite the attempts, the therapy addressed brought mutilations to the patient, leading to functional, aesthetic and quality of life problems.

Because the treatment generates mutilation, according to Costa et al. (2010) an alternative for maxillary reconstruction is through surgery, but it will depend on the extent of the defect, and bone and caritillamid grafts, pedicled flaps, microvascularized free flaps, intraoral, extraoral or zygomatic implants can be used. Another method for rehabilitation is through the obturator prosthesis, which has been considered the gold standard in palatine reconstruction, because in addition to providing rapid patient repair, it will allow more careful follow-up in episodes of recurrence (DEPPRICH et al., 2011). It is recommended for situations where surgery to close the defect is contraindicated, cases of extent of mutilation, age of the patient and in situations of evidence for recurrence of the lesion (SANTOS et al., 2003). Therefore, the treatment of choice for the patient was conservative through the obturator prosthesis, which was a favorable alternative, because it was possible to follow-up and detect recurrence of the lesion.

For the making of the palatine shutter, the literature has a faster and more effective system called Computer Aided Design-Computer Aided Manufacturing (CAD-CAM) (KAWAHATA et al., 1997). However, due to its high cost, it became unfeasible for the case in question, being the most convenient the conventional technique for the elaboration of the obturator prosthesis. Its preparation is complex, and any procedure that can be used to minimize the patient’s suffering should be adopted. The patient used a prosthesis with retention problems

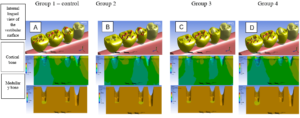

Thus, because the patient already makes use of a shutter prosthesis, it is possible to choose to perform the cloning technique (DA CUNHA DINIZ et al., 2015), even though it was without adequate retention because it had passed the useful life of 3 years (ANTUNES et al., 2008), it was correctly constructed and restored adequate functional space. According to Gomes and Castro (2009) the technique consists in the realization of the silicone matrix, and the inclusion in muffle and for the duplication of teeth recommend fluid silicone, as it will prevent the formation of bubbles and irregularities. In this case, the technique underwent some modifications made by the authors to ensure greater agility to the procedure. The material of choice to obtain the replica of the base was the acrylic resin duralay, because it presents little polymerization contraction. As for the tooth region, it was made with wax 7, where in the next phase the teeth copied in wax were replaced by the stock teeth directly. The modifications showed a good cost-benefit ratio, not requiring the laboratory stage of acrylization in a conventional oven or microwave for the preparation of the clone.

To perform the final stage of the prosthesis a very relevant factor is acrylization. Wu & Schaaf (1989) showed that hollow shutter acrylization decreases weight from 33.06 to 6.55%, depending on the size of the defect. The literature indicates that lighter prostheses provide favorable retention and stability. Among its advantages is in the aid of swallowing, improvement in retention, preventing the overtaking of food and liquids through the maxillary defect. Factors that were fundamental for the choice of acrylization of the prosthesis in evidence.

Through histopathological examinations of the last surgeries performed on the patient, which indicated margin compromise, a more invasive surgery was planned by her physicians, which may compromise noble structures of facial support. Thus, facial molding was proposed, being as a guide for possible aesthetic-functional rehabilitation, after inavasive surgical procedure. The materials described in the literature for the preparation of facial molding are elastomers, hydrocolloides and plasters (AQUINO et al., 2012). The chosen technique is quite usual, low cost and easy execution, the material of choice for the case was irreversible hydrocolloside and plaster. Alsiyabi and Minsley (2006) mention that the conventional technique using irreversible hydrocolloide can result in inaccuracy and distortion of molding. Then, the authors propose the use of silicone, which will reduce clinical clothing and the fact that the material presents dimensional stability, deformation resistance and high tear resistance. On the other hand, the main disadvantage is the high cost of the material. Thus, facial molding performed with irreversible hydrocolloide proved to be effective, without distortions and low cost.

4. CONCLUSION

The obturator prosthesis is an effective alternative in the rehabilitation of patients undergoing surgical resections, which resulted in mutilations. Thus, the choice of cloning technique with some modifications, in this case, in addition to better cost-benefit, reduced the number of clinical and laboratory stages, resulting in the replacement of the old prosthesis more quickly and effectively. In addition, the role of this rehabilitation in the reintegration of the individual into the biopsychosocial environment, the restoration of function, aesthetics and comfort, is of great relevance. As for facial molding, because it is a noninvasive procedure, it can be performed prior to surgery of neoplastic lesions of the face region, because the resulting model will be of great help in future prosthetic reconstruction.

5. REFERENCES

ADELSTEIN, David J. et al. Biology and management of salivary gland cancers. In: Seminars in radiation oncology. WB Saunders, 2012. p. 245-253.

ALSIYABI, Abdullah S.; MINSLEY, Glenn E. Facial moulage fabrication using a two‐stage poly (vinyl siloxane) impression. Journal of Prosthodontics: Implant, Esthetic and Reconstructive Dentistry, v. 15, n. 3, p. 195-197, 2006.

AQUINO, Luana Maria Martins de et al. Técnicas de moldagem da máscara facial. Revista de Odontologia da UNESP, v. 41, n. 6, p. 438-441, 2012.

ANTUNES, Antonio Azoubel et al. Utilização de implantes ósseointegrados para retenção de próteses buco-maxilo-faciais: revisão da literatura. Rev cir traumatol buco-maxilo-fac, v. 8, n. 2, p. 9-14, 2008.

ARTOPOULOU, Ioli Ioanna et al. Effects of sociodemographic, treatment variables, and medical characteristics on quality of life of patients with maxillectomy restored with obturator prostheses. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry, v. 118, n. 6, p. 783-789. e4, 2017.

BADADARE, Mokshada M. et al. Comparison of obturator prosthesis fabricated using different techniques and its effect on the management of a hemipalatomaxillectomy patient. Case Reports, v. 2014, p. bcr2014204088, 2014.

BRANDWEIN, Margaret S. et al. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study of 80 patients with special reference to histological grading. The American journal of surgical pathology, v. 25, n. 7, p. 835-845, 2001.

CAMPANA, Igor Gusmão; GOIATO, Marcelo Coelho. Tumores de cabeça e pescoço: epidemiologia, fatores de risco, diagnóstico e tratamento. Revista Odontológica de Araçatuba, p. 20-31, 2013.

CASTRO, Osmar; GOMES, Tomaz. Execução da clonagem até a instalação da prótese. In: CASTRO, Osmar; GOMES, Tomaz. Técnica da clonagem terapêutica em prótese total. São Paulo: Santos, 2009. p. 41-8.

COSTA, Sérgio Moreira et al. Reconstrução da maxila. Rev Bras Cir Craniomaxilofac, v. 13, n. 3, p. 165-8, 2010

DA CUNHA DINIZ, Alexandre et al. Duplicação rápida de prótese total: passo-a-passo. Revista Ciência Plural, v. 1, n. 3, p. 85-92, 2015.

DEPPRICH, R. et al. Evaluation of the quality of life of patients with maxillofacial defects after prosthodontic therapy with obturator prostheses. International journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery, v. 40, n. 1, p. 71-79, 2011.

DE SOUSA BARBOSA, Renata Pereira et al. Neoplasias malignas de glândulas salivares–estudo retrospectivo. Revista Odonto Ciência, v. 20, n. 50, p. 361-366, 2005.

FRANÇA, Diurianne Caroline Campos et al. Carcinoma mucoepidermóide: relato de caso. Rev. Odontol. Araçatuba, p. 20-23, 2008.

GASTALDI, G. et al. Prosthetic management of patients with oro-maxillo-facial defects: a long-term follow-up retrospective study. Oral Implantology, v. 10, n. 3, p. 276, 2017.

GIOVANINI, Ellen Greves et al. Carcinoma mucoepidermóide de palato–descrição de um caso clínico. Revista da Faculdade de Odontologia-UPF, v. 12, n. 1, 2007.

GUZZO, Marco et al. Major and minor salivary gland tumors. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology, v. 74, n. 2, p. 134-148, 2010.

HYAM, D. M.; VENESS, M. J.; MORGAN, G. J. Minor salivary gland carcinoma involving the oral cavity or oropharynx. Australian dental journal, v. 49, n. 1, p. 16-19, 2004.

KAWAHATA, N. et al. Trial of duplication procedure for complete dentures by CAD/CAM. Journal of oral rehabilitation, v. 24, n. 7, p. 540-548, 1997.

KROLLS, Sigurds O.; TRODAHL, John N.; BOYERS, Col Robert C. Salivary gland lesions in children. A survey of 430 cases. Cancer, v. 30, n. 2, p. 459-469, 1972.

LIKHTEROV, Ilya et al. Locoregional recurrence following maxillectomy: implications for microvascular reconstruction. The Laryngoscope, v. 127, n. 11, p. 2534-2538, 2017.

OZAWA, Hiroyuki et al. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the head and neck: clinical analysis of 43 patients. Japanese journal of clinical oncology, v. 38, n. 6, p. 414-418, 2008.

RETTIG, Eleni M.; D’SOUZA, Gypsyamber. Epidemiology of head and neck cancer. Surgical Oncology Clinics, v. 24, n. 3, p. 379-396, 2015.

REZENDE, José Roberto Vidulich. Prótese nas grandes perdas da maxila. In: REZENDE, José Roberto Vidulich et al. Fundamentos da prótese buco-maxilo-facial. 1997.

SANTOS, Gilda da Cunha et al. Neoplasias de glândulas salivares: estudo de 119 casos. Jornal Brasileiro de Patologia e Medicina Laboratorial, v. 39, n. 4, p. 371-375, 2003.

SOUSA, Andréa Rodrigues de et al. Perfil clínico-epidemiológico de pacientes com câncer de cabeça e pescoço em hospital de referência. Rev. Soc. Bras. Clín. Méd, v. 14, n. 3, p. 129-132, 2016.

WU, Yn-low; SCHAAF, Norman G. Comparison of weight reduction in different designs of solid and hollow obturator prostheses. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry, v. 62, n. 2, p. 214-217, 1989

Attachments

Annex 1

Annex 3

Annex 4

[1] Graduated in Dentistry, Nilton Lins University.

[2] Doctor of Public Health. Specialist in Dental Prosthesis. Professor of Total Prosthesis and Occlusion, Dentistry Course, Nilton Lins University.

[3] Specialist in Oral-maxillofacial Surgery and Traumatology. Professor of Internship in Oral Surgery I, Dentistry Course, Nilton Lins University.

[4] PhD in Dentistry – Oral Pathology. Specialist in Oral Pathology. Professor of Oral Pathology, Dentistry Course, Amazonas State University.

[5] Master’s degree in Dental Clinic. Specialist in Dental Prosthesis. Professor of Total Prosthesis, Fixed Prosthesis, Removable Prosthesis and Occlusion, Dentistry Course, Amazonas State University.

Sent: April, 2020.

Approved: July, 2020.