NARRATIVE REVIEW

ARAÚJO, Marhia Eduarda Vilela de [1], PESSOA, Juliana Victória de Sousa [2], COSTA, Maria Beatriz Tavares da [3], CAMPOS, Gabrielly Caldeira [4], ARAUJO, Priscila Pinto Brandão de [5], ALVES FILHO, Ary de Oliveira [6]

ARAÚJO, Marhia Eduarda Vilela de. et al. Treatment of Class III malocclusion with Balters’ bionator in pediatric and adolescent patients: a narrative review. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 08, Issue 08, Vol. 02, pp. 94-119. August 2023. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/dentistry/class-iii-malocclusion, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/dentistry/class-iii-malocclusion

ABSTRACT

The World Health Organization (WHO) emphasizes that malocclusion ranks third in the priorities of global public dental health issues, given its widespread prevalence, qualifying it as a matter of public health relevance. Anterior crossbite is characterized by the improper positioning of the upper anterior teeth, which overlap inside compared to the lower teeth. This specific occlusal discrepancy requires timely intervention to prevent worsening, potentially progressing to a skeletal stage in adulthood, where correction often demands orthognathic surgical procedures. In this context, the purpose of this study was to conduct a comprehensive literature review to illustrate the relevance of early treatment of anterior crossbite using an adaptation of the Bionator appliance by Balters. This method was employed to address Class III malocclusion in the mixed dentition phase. The analysis aimed to determine the effectiveness of this approach when implemented early, in order to satisfactorily address this occlusal irregularity.

Keywords: Malocclusion, Anterior crossbite, Angle’s Class III, Balters’ Bionator.

1. INTRODUCTION

Malocclusion, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), ranks third in occurrence among oral health problems, surpassed only by cavities and periodontal disease. Factors of genetic, environmental, and ethnic origin play significant roles as primary contributors to the onset of this condition (ARAÚJO, 2023).

Certain types of malocclusion, notably Class III relationships, tend to have a hereditary manifestation, establishing a substantial connection between genetics and the occurrence of malocclusions. Similarly, the ethnic component also influences, with bimaxillary protrusion occurring more prevalently in individuals of African descent compared to other ethnic origins. Consequently, malocclusion can be interpreted as a multifactorial condition, the precise cause of which has not yet been clearly defined to date (ALHAMMADI et al., 2018).

Research indicates that the malocclusion rate in Brazil, Classes II and III of canines, was observed in 16.6% and 6.4% of the population, respectively. Anterior crossbite was present in approximately 3% of Brazil’s population, with no significant differences between regions, according to the SB Brazil 2010 survey. In Brazil, the Unified Health System (SUS) does not effectively address occlusion problems, given that a considerable part of society relies solely on the public health system; thus, it is likely that many patients with malocclusion are not receiving proper guidance (BOEK et al., 2010; ARAÚJO et al., 2023). Due to its high prevalence, malocclusion is recognized as a public health issue capable of impacting an individual’s quality of life, compromising social interactions and psychological balance (DUTRA et al., 2018).

Anterior crossbite occurs when there is an incorrect relationship of the upper and lower anterior teeth, in which the upper teeth occlude inside in relation to the lower teeth, according to Litton et al.‘s definition (1970). The absence of treatment for this anterior crossbite in childhood and adolescence can result in progressive worsening, culminating in a skeletal malocclusion in adulthood. The complexity of this situation may vary depending on the number of affected teeth; consequently, a greater number of teeth involved tends to increase the likelihood of developing the Class III skeletal pattern. This development occurs gradually due to the progressive compromise between dental and skeletal elements, coupled with the functional imbalance of the stomatognathic system.

Several studies have examined the effects of malocclusion on quality of life. However, there is a gap regarding studies investigating this impact in the mixed dentition phase. According to Dutra et al. (2018), most investigations on the effects of malocclusion have focused on adolescents and adults. Conducting early treatment during the mixed dentition and childhood growth period provides the opportunity to direct development and intervene early in malocclusions, as stated by Freitas; Freitas and Silva (2012). Therefore, the orthopedic approach demonstrates effectiveness in redirecting the patient’s craniofacial growth.

Among the different available approaches, the Balters’ Bionator, a functional orthopedic appliance created by Wilhelm Balters in 1952, is a functional orthopedic maxillary activator used in Class II treatment to promote mandibular repositioning. Bigliazzi et al. (2015) states that modifying this device for the treatment of Class III malocclusion aims to promote restriction and reorientation of mandibular growth, thus correcting the prognathic mandibular condition.

Over the past decades, much has been studied about early facial orthopedics and its treatment successes.

Therefore, any information capable of elucidating the effectiveness of early treatment during the deciduous dentition or early stages of mixed dentition is relevant. An important question is whether the induced alterations in skeletal or dental relationships from early treatment will be permanent (GODT et al., 2008). Reflecting on this, the importance of using Balters’ Bionator as science advances and the impact this type of appliance has on the lives of individuals undergoing this treatment was observed.

2 LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1 MALOCCLUSION ASSOCIATED WITH QUALITY OF LIFE IMPACTS AND AS A PUBLIC HEALTH ISSUE

Quality of life is a comprehensive concept that encompasses various aspects, such as individual perception of physical, psychological, and social functions, along with a subjective sense of well-being. Oral health is fundamental for good quality of life, as it can impact children’s feeding, smile, speech, and socialization.

Facial expression has an impact on self-esteem and emotional balance, playing a significant role in social interactions. Changes in these areas, in turn, will have direct effects on children’s quality of life (CORLESS; NICHOLAS; NOKES, 2001; OLIVEIRA; SHEIHAM, 2004).

Thus, malocclusion is an oral condition that has increased in prevalence in recent centuries. Its presence causes functional problems in the craniofacial system and a negative impact on the quality of life of children and their families. Therefore, identifying its incidence within a specific population can contribute to the formulation of public health policies aimed at preventing, intervening, and treating the most common issues among individuals in this group (GRANDO, et al., 2008; ARAUJO et al., 2023).

Suliano et al. (2007) conducted a cross-sectional study where the prevalence of dental malocclusion was 82.1% in the population randomly selected from 11 schools (n=173, 95% CI 76.4-87.8). These findings highlight the existence of a considerable and unmet demand for orthodontic treatments, with the severity of malocclusions being directly related to the likelihood of associations with functional problems. This aspect should be considered when planning public services to address these conditions. Although they are generally treated in adolescents and adults, they manifest at an early age. In Brazil, some studies report that 75.5% to 89.3% of the Brazilian population may have some type of malocclusion (GRANDO et al., 2008).

According to Boek et al. (2010), malocclusion can manifest in different degrees of severity, making it important to prioritize treatments according to need. Early diagnosis and intervention of occlusal alterations have a significant impact on individual growth, often preventing future complications and the need for surgical approaches.

In the context of epidemiological data, the most recent study on Oral Health in Brazil, known as SB Brazil 2010 and published by the Ministry of Health, demonstrated a prevalence of 36.46% of malocclusions in the Brazilian population, divided into categories of mild, moderate, and severe severity. Among five-year-old children, mild malocclusion was the most common, with an incidence of 22.1%, followed by moderate or severe problems (14.5%). In twelve-year-old children, a prevalence of 21% was observed for problems classified as very severe, highlighting the potential worsening of malocclusion over time and emphasizing the importance of early treatment.

According to Morais et al. (2014), malocclusions are considered public health issues, especially due to their prevalence and their impact on young children. The epidemiological situation of oral health in Brazil reveals deficiency levels that deserve attention. Children in Brazil have one of the highest rates of early tooth extractions, without proper maintenance of the lost space. Additionally, untreated extensive cavities represent aggravating factors in the origin of malocclusions, which rank third in the hierarchy of priority problems related to oral health in the country.

Martins (2019) assessed the association of malocclusion in twelve-year-old individuals with individual and contextual factors and showed that individuals belonging to sanitary districts with worse conditions in basic sanitation, housing, family income, and education had a higher prevalence of malocclusion.

Another nationally conducted study in Brazil revealed that twelve-year-old individuals residing in areas with a significant proportion of families dependent on government social assistance, lower Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and poor population health care performance had a higher malocclusion index. Therefore, early detection and treatment of individuals with malocclusion are important, especially in the context of public health responsibility, since this directly impacts treatment costs. This is because preventive and interceptive orthodontic approaches have the potential to improve occlusion during adolescence and pre-adolescence stages (MARTINS et al., 2019).

Dutra et al. (2018), when evaluating 8 to 10-year-old students from the public schools in Belo Horizonte, reported that 58.1% of the children exhibited normal occlusion or mild malocclusion, while 27.8% had a clearly defined severe malocclusion. Furthermore, 11.5% had a severe malocclusion, and 2.6% were identified with an extremely severe malocclusion.

Well-established studies like that of Boek et al. (2013) identified an incidence of malocclusion of 80.29% among students aged 5 to 12 enrolled in the municipal network of Araraquara, São Paulo. The most common dental relationship was Class I for molars (63.28%), followed by Class II (25.66%), and finally Class III (1.49%).

For Fernandes et al. (2020), the presence of malocclusion in students aged 7 to 17 from the municipal and state networks of Augusto Correa, Pará, was observed in 100% of cases. Among these individuals, 42.9% had Class I malocclusion, 41.7% exhibited Class II malocclusion, and 15.4% had Class III malocclusion.

More recent studies like that of Carneiro et al. (2021), conducted in the municipality of Mineiros, Goiás, with children aged 3 to 12 years old, observed that of the identified malocclusions, 42% had Class I, followed by 39% Class II, and 13% Class III. Regarding the frequency of open bite in incisor relationship, it was identified that 23% of patients had this condition, while 29% had deep bite. Additionally, 16% of the analyzed children exhibited anterior crossbite, and 15% had posterior crossbite.

3. DEFINITION AND CLASSIFICATION OF MALOCCLUSIONS

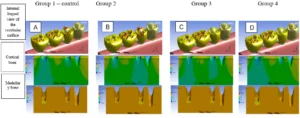

In 1972, Andrews conducted a study that identified “The six keys to normal occlusion,” describing the fundamental characteristics of dental occlusion from a morphological standpoint. This research also served as a guide for the appropriate finalization of orthodontic treatments. In his study with orthodontic models of individuals with considered normal occlusion, Andrews recognized and established six keys of occlusion: Molar relationship – the mesio-vestibular cusp of the upper permanent first molar occludes within the groove existing between the mesio-vestibular cusp and the median of the lower first molar; crown angulation – the cervical portion of the long axis of each crown is distal to its occlusal portion; crown inclination – the cervical portion of the long axis of the crown of the upper incisors is lingually positioned to the incisal surface, increasing lingual inclination progressively in the posterior region; rotations – there should be no undesirable dental rotations; interproximal contacts – there should be no interproximal spaces; curve of Spee – it should be flat or smooth.

The author mentioned that the keys were not linked to a specific structure but served as a reference to evaluate orthodontic patients. The absence of one or more keys would indicate an inadequate occlusion.

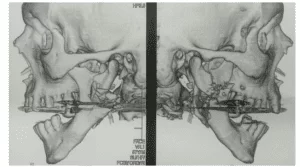

Figure 1 – Sample of normal occlusion according to Andrews

Defines malocclusion as an altered relationship of disproportionate parts. Its modifications can affect four systems simultaneously: teeth, bones, muscles, and nerves (LITTON, 1970). Since the early days of orthodontics, prominent researchers like Kingsley, Case, and Angle emphasized the importance of the interrelation between aesthetics and this specialty (LANDÁZURI et al., 2010).

The first description of the ideal occlusion, by Angle, refers to the stable positioning of the upper first permanent molar within the craniofacial skeleton, and discrepancies occur due to anteroposterior changes in the lower arch in relation to it (VELLINI, 2008).

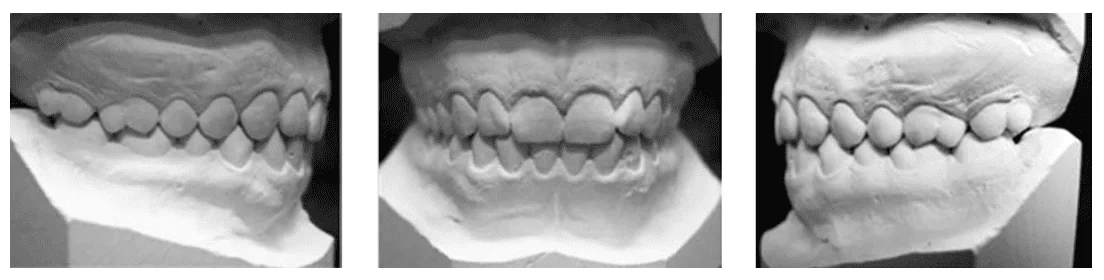

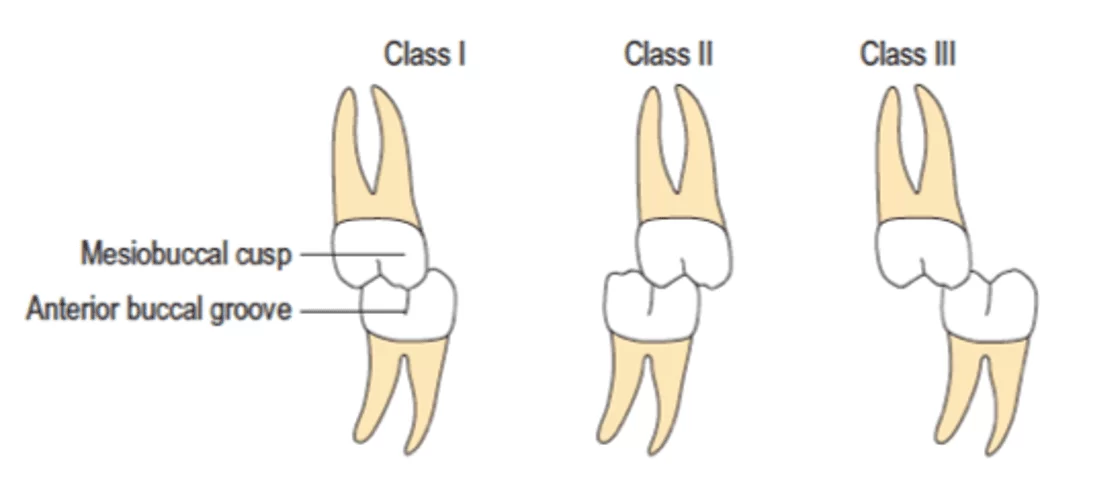

Regarding the categorization of malocclusions, it is acknowledged that: Class I, or neutroclusion: In this configuration, the mesiobuccal cusp of the upper first molar fits into the mesiobuccal groove of the lower first molar. This can result in disharmonies in both dental and bony structure, leading to crowding or dental rotations in the anterior region. Class II, or distocclusion: Characterized by a distocclusion, in this case, the mesiobuccal cusp of the upper first permanent molar occludes in front of the mesiobuccal groove of the lower first permanent molar. The anterior teeth are in a non-ideal position, resulting in disharmony. Class II is subdivided into two categories:

a) Division 1: Presents vestibular inclination of the upper incisors. The teeth are well aligned in the dental arch, but the Spee curve is more pronounced, leading to an increased overjet. This occurs due to the buccal positioning of the upper incisors, which may or may not result in a pronounced overbite.

b) Division 2: Characterized by an anterior-superior disharmony, resulting in the uprighting or lingualization of the upper incisors. This leads to a pronounced overbite, with the possibility of a pronounced overjet as well. The facial aspect tends to be pleasant.

Class III: In this type of malocclusion, the mesiobuccal cusp of the permanent maxillary first molar occludes between the permanent mandibular first molar and second molar (ANGLE, 1907).

Figure 2 – Molar classification according to Angle

In individuals classified as Class III, the convexity is reduced, resulting in a straight or concave profile. The mid-face region often exhibits deficiencies, even when it appears to be in a normal state. This is because mandibular excess displaces the soft tissue from the maxilla to the posterior part, resulting in the concealment of zygomatic projection. Regarding the lower face region, an increase tends to occur, especially in cases of prognathism. Furthermore, the relationship between the chin and the neck appears normal in individuals with maxillary deficiency or excessive in prognaths (CARDOSO et al., 2011).

In addition to these aspects, anterior crossbite malocclusions are particularly notable due to the functional interference and modifications they promote in the development of the face and teeth, resulting in noticeable deformities that affect both the aesthetics and functionality of the stomatognathic system. Anterior crossbite occurs when there is an abnormal vestibulo-lingual relationship between the upper and lower incisors, leading to aesthetic and functional complications in the stomatognathic system. This condition is quite common in patients classified as Class III by Angle (ROSSI et al., 2012).

According to Moyers (1991), the classification of malocclusions based on the involved tissue is the most reliable method to determine differences in similar clinical conditions, considering the likely site of origin. Skeletal malocclusions, also known as skeletal malformations, encompass problems related to abnormal growth, size, shape, or proportions of the bones in the craniofacial complex. For example, Class III cases may resemble mandibular hypertrophy. These clinical conditions can originate from genetic factors or other dysfunctions, while each region of the craniofacial complex has a growth capacity that can be shaped by the environment.

Numerous studies have indicated that approximately 20% of patients with a Class III malocclusion accompanied by an anterior crossbite can be treated during the mixed dentition phase. In this phase of development, it is possible to correct an isolated problem or provide preliminary treatment (GIANCOTTI et al., 2002). If the treatment is carried out at a later stage of maturity, its resolution can become complex.

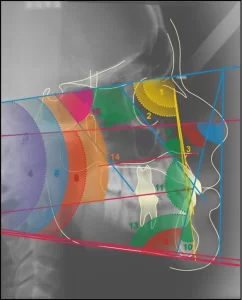

3.1 CEPHALOMETRY: A DIAGNOSTIC EXAMINATION

With the advent of teleradiography, it became possible to evaluate various cephalometric measurements of interest to orthodontists, benefiting numerous professionals and institutions that have dedicated themselves to developing techniques and approaches to characterize the skeletal architecture of the face. Compiling various cephalometric measurements led to the emergence of cephalometric analyses that provide insights into sizes, shapes, relative positions, and orientations of craniofacial components.

In its early days, cephalometry was more closely related to scientific research and anatomical craniometry than to orthodontics. Later, it proved to be a valid method for diagnosis, evaluation of normality patterns in the craniofacial complex, growth monitoring, treatment planning, and assessment of therapeutic outcomes (GANDINI JR et al., 2005).

Since the introduction of cefaslotato, several cephalometric analyses have been developed, including Tweed, Downs, Steiner, Ricketts, McNamara, Wits, among others. Through these analyses, it is possible to describe, compare, classify, and communicate clinical cases. These methodologies use standards of normality, either numerical or morphological, to compare the skeletal, dental, and facial characteristics observed in the patient (GANDINI JR et al., 2005).

Cephalometric radiography is a technique used to diagnose craniofacial deformities, allowing measurements of the skull base, hyoid bone position, mandibular configuration, posterior pharyngeal airway space, tongue dimensions, uvula thickness, and length, among other aspects, to be obtained (GANDINI JR et al., 2005; SALLES et al., 2005).

Cephalometric analysis is the most suitable tool for studying variations in the craniofacial skeleton, while other structures, such as soft tissues, are affected secondarily. Orthodontic treatment should be planned to correct the underlying bone dysplasia or accommodate the dentition to it, as in cases of compensatory dental movements. Orthopedic appliances can influence the dentoalveolar level and also have a deeper effect on the basal bone, providing an orthopedic effect (FERES; VASCONCELOS, 2009).

3.2 DEFINITION OF CLASS III MALOCCLUSION

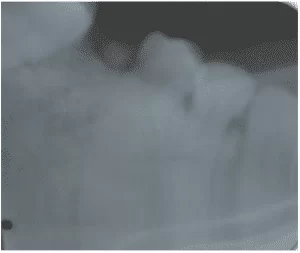

In Class III treatment, the diagnosis is conducted through facial analysis, cephalometric analysis, dental diagnosis which should include panoramic/periapical radiographs and study models, and functional diagnosis where prematurity conditions should be detected, especially in patients in the early stage of transitioning from primary to permanent dentition, deserve special attention (FERES; VASCONCELOS, 2009).

Malocclusions arising from muscle dysfunctions, also known as functional malocclusions, involve problems related to the improper functioning of muscles, in which persistent alterations can lead to distortions in the growth of facial bones or dental misalignments. These muscle alterations are often a result of acquired habits and patterns and, therefore, can also be modified. In the field of orthodontics, there is an almost unanimous consensus that the neuromuscular aspects of malocclusion should be treated as early as possible (ARAÚJO; ARAÚJO, 2008).

Dental malocclusions are associated with teeth and supporting structures. The improper positioning of teeth is generally easier to intercept and control. However, caution should be exercised when diagnosing such misalignment as the primary problem or as a secondary issue resulting from another alteration.

A verdadeira Classe III de Angle, ou mesioclusão, é uma displasia esquelética que envolve uma hipertrofia mandibular, acentuado encurtamento da face média ou combinação destes dois. A aparente ou pseudoclasse III é uma má relação posicional, um reflexo funcional da protração mandibular. A terceira condição, a simples linguoversão de um ou mais dentes anteriores superiores, é uma inclinação axial normal dos incisivos superiores sem nenhuma característica real da Classe III. Deve ter sido notado que a primeira condição é um problema de morfologia esquelética e de morfologia óssea, o segundo, um reflexo muscular adquirido e o terceiro, um problema de posicionamento dentário. Em todas as três condições, os dentes anteriores superiores estão atrás da mandíbula, mas apenas os dois primeiros mostram os molares inferiores à frente de suas posições normais (MOYERS, 1991, p. 352).

Class III malocclusion is a type of dento-skeletal deviation with a prevalence ranging from 3% to 13% of the population, according to various records.

3.3 CLASS III TREATMENT APPROACHES

Moyers (1991), when addressing force systems in orthodontics and functional orthopedic appliances, conceptualizes them as natural or biomechanical. In natural forces, the author describes that energy resulting from facial muscle contraction or jaw movement can be transferred to craniofacial structures through functional devices. These devices can also be used to strengthen, redistribute forces, or condition the involved musculature. On the other hand, biomechanical forces refer to an artificial force system, where energy is generated by mechanical devices such as auxiliary springs and vertical loops in arches.

Facial orthopedics operates through neural stimulation, activating the muscles and nerves of the face and mouth. When the positions of the jaw, tongue, and temporomandibular joint (TMJ) are altered and corrected, this response is also reflected in bones, gums, and teeth. Therefore, it stimulates the growth and development of the jaws, directs tooth eruption, and achieves sufficient space for positioning and aligning permanent teeth.

It is aimed at altering the shape of the dentofacial appliance to achieve an architecture more suitable for function. Its action is not limited to the dental arch alone but extends to the midfacial craniofacial structures, as well as crucial vital functions, including muscular, respiratory, and phonetic aspects.

Early treatment during the mixed dentition phase and during a child’s growth allows for redirecting growth and intervening early in malocclusions. Therefore, orthopedic treatment is effective for redirecting the craniofacial growth of the patient. It is known that patient cooperation is recognized as one of the main success factors in orthodontic treatment outcomes, especially when removable appliances are used.

Moss’s Functional Matrix Hypothesis (1968) is widely accepted as it proposed that bone and cartilage develop in response to the intrinsic growth of related tissues (functional matrices). This concept influenced all theories and conceptions of craniofacial growth. Mechanical epigenetic factors, largely known as function (or exercise), play a significant role in controlling musculoskeletal development and maintaining structural and physiological characteristics.

Therapeutic goals in the treatment of Class III malocclusions depend on the skeletal component involved (maxilla and/or mandible), developmental stage, presence of active growth (maturation or aging), and facial acceptability (pleasant, acceptable, or unpleasant). These goals should, as much as possible, be influenced by the patient’s or their guardian’s complaint. Early treatment results in beneficial modifications in both the maxilla and the mandible, while late treatment tends to primarily result in significant mandibular restriction. In early treatment, size changes in the mandible are more closely related to changes in its shape. Achieving complete correction of the occlusion is more directly related to changes in the skeleton than in dental structures.

3.4 BIONATOR APPROACHES FOR CLASS III

Various types of treatments can be used for treating Class III patients. One of them is the maxillary reverse-pull headgear, which utilizes expansion appliances such as Hass or Hyrax types. This device was designed with the aim of stimulating skeletal expansion of the maxilla and vestibular inclination of the upper incisors while simultaneously maintaining the position of the lower incisors (LI; MASOUD; VOSS, 2013).

Additionally, the Hickham chin cup can also provide positive outcomes for mandibular retrusion (restraint) (ARAÚJO; ARAÚJO, 2008). The Bimler appliance is another option that can improve Class III cases, promoting more balanced growth of the face both in the muscular and dental aspects.

Another approach is the use of the Lip Bumper (LB), a removable appliance that aids in lip and muscle posture, reducing excessive forces on the lower anterior teeth and preventing vestibularization (ALMEIDA et al., 2006; RETAMOSO et al., 2006; GERZSON; NOBRE, 2011; JACOB et al., 2014; PIZZOL et al., 2004). The Frankel appliance functions similarly to other types of functional appliances, following the concept of repositioning the mandible more posteriorly (VALARELLI et al., 2014).

The Progénico removable appliance can also be used, and the Aschler arch is recommended to correct functionally based anterior crossbites, showing satisfactory responses resulting in proper occlusion and neurofunctional normalization. This appliance not only aligns the teeth but also directs mandibular growth and promotes maxillary development (TERADA et al., 1997).

3.5 BIONATOR APPROACH FOR CLASS III

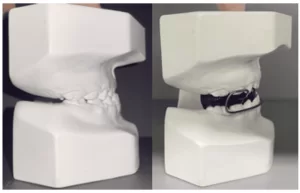

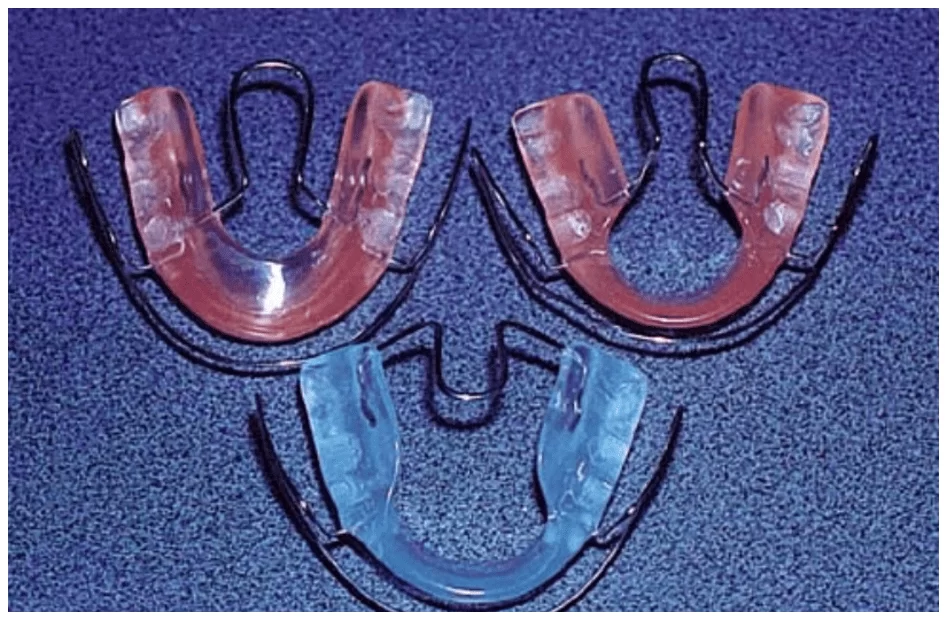

Among the different available approaches, Balters’ Bionator, a functional orthopedic appliance created by Wilhelm Balters in 1952, is a functional maxillary orthopedic activator used in the treatment of Class III malocclusion to correct mandibular prognathism. This type of appliance operates by stimulating maxillary growth through “coffin” type springs or expanders in the palate, aiming to enhance transversal development. It also controls the anterior growth of the mandible using the vestibular arch and lateral loops, seeking to achieve a new postural position of the lower arch. These actions promote significant changes both in the dental and skeletal aspects, resulting in noticeable improvements in the facial profile (BIGLIAZZI et al., 2015).

This appliance aims to create an anterior oral seal, causing the back of the tongue to position itself near the soft palate region. Additionally, it aims to expand the intraoral space in a physiological manner, improving masticatory, speech, and breathing functions. The approach also includes positioning the incisors in a tip-to-tip contact, lengthening the maxilla to increase oral space, facilitating tongue accommodation. The objective encompasses improving the relationship between the jaws, tongue, dentition, as well as the surrounding soft tissues, culminating in the correction of mandibular protrusion. The use of this appliance is recommended for approximately fourteen hours a day until the first signs of correction of anterior crossbite are observed (BACCETTI; TOLLARO, 1998).

According to Ortolani-Faltin and Faltin Junior (1998), the Inverted Bionator used in correcting mandibular prognathism has an acrylic base identical to the Base Bionator. It is made in a more retrusive construction bite, in greater height than tip to tip. Its palatal loop has an oval anterior path, being open towards the posterior, and aims to excite the tip of the tongue, altering its posture. It also has lower and buccinator vestibular loops that do not fold in the horizontal superior direction.

The reverse type Bionator was introduced by Balters as an approach to treating Class III malocclusion. Its purpose is to exert pressure on the lower arch, releasing the upper alveolar region and stimulating the desired growth, especially during the eruption of permanent incisors.

There are three main types of Bionators, each aimed at correcting different skeletal anomalies and functional alterations: base, inverted, and closed Bionators. Below are the components of the Bionator and their main functions, according to Balters’ description:

1- Occlusion plane: It is an acrylic plane oriented parallel to the Camper’s plane. It will guide the teeth shortly after eruption.;

2- Palatal strap: placed in the acrylic base, between the tongue and the palate. It serves to support the body of the bionator and guide the positioning of the tongue;

3- Vestibular strap: it consists of two parts:

– Lip strap: stimulates lip sealing.

– Buccinator strap: a continuation of the lip strap that occupies the space between the dental arch and the buccinator muscle. It will prevent interference of the soft tissues of the cheeks with the dental arches.

3 – Vertical supports: Ensure a permanent fixation of functional occlusion. They should prevent deviations of the mandible in the vertical plane. When reduced using burs, sliding areas are formed until the tooth reaches the occlusion plane.

4 – Interproximal supports: Prevent anteroposterior sagittal deviations of the Bionator (ORTOLONI – FALTIN & FALTIN – JUNIOR., 1998).

Figure 3 – Types of Bionator appliances by Balters

The inverted Bionator is used to correct mandibular prognathism. Its components are as follows: construction bite obtained in the most retruded position, in an anteroposterior and vertical direction, slightly above edge-to-edge to allow correction of anterior crossbite; acrylic base similar to the Base Bionator; palatal strap placed in an inverted manner, inserting into the distal area of the upper first molars and following an anterior oval path. The anterior part is at the height of the first premolars or deciduous molars. The inverted palatal strap aims to alter the position of the tongue, stimulating its backward action; vestibular strap, where the buccinator parts are equivalent to the Base Bionator. However, the labial part does not have upper and horizontal folds in the region of the upper anterior teeth. Its path continues inferiorly, contouring the lower teeth (should not be activated against the teeth).

According to Stutzmann and Petrovic (1982), after a conducted analysis, the Bionator is essentially a functional device, the degree of effectiveness of which depends primarily on the additional advancement of the mandible. This advancement is most noticeable in cases of anterior rotational growth of the mandible. Furthermore, they concluded that the Bionator is effective in inducing additional growth in the condylar cartilage and the posterior edge of the ascending ramus, resulting in extra elongation of the mandible.

Carels and Van Der Linden (1987) stated that the use of the Bionator influences both the nasomaxillary complex and the mandible, in sagittal and vertical terms. Whenever the patient uses the appliance, a comprehensive force acts in an anterior and inferior direction on the mandible, and a posterior and superior direction on the maxillary complex.

3.6 DAILY WEAR TIME

The duration of treatment for correcting Class III malocclusion using removable mandibular retraction appliances was fourteen hours per day until the first evidence of correction of the anterior crossbite, maintaining nighttime use until the end of the observation period (GALLÃO et al., 2013).

In the year 2003, Giancotti et al. published a case study article addressing the treatment of Class III and pseudo-Class III conditions using the Bionator appliance by Balters. The article presents three case reports: the first patient was eight years and ten months old, presenting anterior crossbite from deciduous canine to canine, and molars had a Class I relationship. The patient used the appliance for sixteen hours a day for eleven months. The second case report involved a nine-year-old patient with pseudo-Class III in the mixed dentition. The treatment aimed to correct mandibular displacement, procline the upper incisors, and provide space for the eruption of the upper right lateral incisor. The Bionator appliance for Class III was used for fourteen to sixteen hours per day over a period of ninety days. The third case report was about a nine-year-old patient with bilateral Class III malocclusion more pronounced on the right side and an anterior crossbite with a midline deviation to the left. The patient used the Class III Bionator for fifteen hours a day for seven months.

4. DISCUSSION

Class III malocclusions associated with craniofacial discrepancies pose a particular challenge for treatment and have a tendency to relapse. From the articles selected in this narrative review, different types of appliances such as maxillary reverse traction with a facial mask, lip-active plate, Frankel appliance, Progénie appliance, and modified Balters Bionator for Class III were evaluated, and it is considered that the earlier the treatment is initiated, the greater the results obtained.

Additionally, as a preventive measure to avoid future surgical treatments in patients with Class III and anterior crossbite, it becomes essential to adopt procedures from the mixed dentition phase that stimulate anterior maxillary growth and direct the mandible posteriorly, inferiorly, and clockwise (ARAÚJO & ARAÚJO, 2008).

The Balters Bionator is widely used in the field of functional orthopedics, being one of the most common devices in this field, along with other devices mentioned by Li et al. (2013), Araújo & Araújo (2007), and Almeida et al. (2006). Besides evaluating the effectiveness of the appliance, it is crucial to take into consideration the period required to achieve substantial changes in craniofacial structures when adhering to a specific dentofacial orthopedic treatment protocol (FALTIN et al., 2003; GALLÃO et al., 2013; GIANCOTTI et al., 2002).

In Godt et al.‘s study (2008), the use of removable appliances, such as prognathism activators and maxillary plates, alone or in combination with a facial mask mounted on a maxillary expansion device, was analyzed. Through this study, it was noted that although the effects found are smaller with exclusively removable appliances, findings from the control group that did not use any type of appliance clearly demonstrated that they are capable of inducing small improvements and neutralizing the progression of Class III malocclusion.

Faltin Jr (2003), when analyzing groups of individuals treated with the Bionator before the pubertal growth spurt in mandibular growth and a group of individuals who started treatment during the pubertal growth spurt, found that significant long-term changes in occlusal and maxillary growth relations can be achieved with Bionator therapy only when functional treatment includes the pubertal growth spurt. Both groups were reassessed after the end of growth (about six years after the end of active Bionator treatment). Furthermore, the post-treatment period in the early and late treatment groups after the spurt included a short phase of fixed appliance therapy to refine and detail the occlusion. Therefore, the changes observed in facial profile, soft tissues, and dental relationship, as described in this case, were positive for the patients.

In Siara-Olds (2010), a group of children, with an average age of ten years and seven months, used four types of appliances, Bionator; Herbst; Twin Block, and MARA, and it was observed that the group of children who used Balters Bionator had a greater amount of lingual inclination of the crowns of the upper incisors. This fact can be attributed to the pressure from the labial arch, and the most effective time for treatment with Bionator, Twin Block, and Herbst appliances is during or slightly after the onset of the pubertal peak in growth.

In another study conducted by Almeida-Pedrin et al. (2007), the effects of the treatment using the HG bite plane and Bionator appliances were compared, suggesting that for the correction of Class III malocclusion, both appliances achieved a significant combination of dentoalveolar and maxillomandibular alterations. Therefore, as demonstrated in other investigations of orthopedic appliances, both the HG bite plane and the Bionator produced lingual inclination and retrusion of the lower incisors. Thus, comparing with the studies reported earlier by Schulhof and Engel (1982), the researchers examined lateral cephalometric radiographs of thirty-three patients with Class III malocclusion who underwent treatment with Bionator and compared the results with the expected growth without treatment. The results achieved revealed that Bionator treatment stimulated greater growth than predicted.

Using the Bionator in the treatment of patients with Class III malocclusion in late mixed dentition, Tsamtsouris and Vendrene (1983) concluded that the improvements observed in facial profile and skeletal structure resulted from releasing the growth potential of the maxilla, previously limited by abnormal orofacial muscle function. Authors like Cardoso et al. (2011) highlighted that using this appliance during the mixed dentition phase could prevent possible fractures in incisors, eliminate damage to the oral mucosa in cases of traumatic deep overbite, and promote lip competence. In addition to its aesthetic benefits, these improvements would have a positive impact on the vertical and horizontal growth patterns of the dentofacial complex.

In Rabie; Gu (2000), the methods to treat Class III malocclusion in permanent dentition encompass the use of fixed orthodontic appliances associated with intermaxillary elastics, extraoral devices, temporary skeletal anchorage, and functional appliances. According to Rédua (2020), the Bionator, being an intraoral appliance, tends to generate fewer adverse reactions in the social context. On the other hand, extraoral devices often have a more noticeable impact on the social sphere due to their influence on aesthetics, often leading to resistance in their use.

5. CONCLUSION

It is important to recognize that oral health is intrinsically linked to overall health, and oral care programs should be approached as fundamental elements within comprehensive health programs, aiming for a holistic approach. Additionally, addressing skeletal and facial disharmonies requires the implementation of corrective orthodontic interventions. The modified Balters Bionator appliance for Class III is considered capable of providing good overall outcomes in terms of function and aesthetics. Various approaches and therapies for Class III malocclusion share common objectives, such as the pursuit of facial aesthetics, preservation of tissue health, achieving stability at the end of treatment, and harmonizing teeth within the oral cavity, resulting in an enhancement of facial proportions. Therefore, when malocclusions not only affect aesthetics but also have implications for an individual’s health and social integration, it is essential for these issues to be incorporated into public health strategies, as they are often undervalued within current health policies.

REFERENCES

ALHAMMADI, M. S. et al. Global distribution of malocclusion traits: A systematic review. Dental Press J Or- thod. v. 23 n. 6 pp. 1-10, 2018.

ALMEIDA, M. R. et al. Placa lábio ativa: versatilidade e simplicidade no tratamento ortodôntico. Revista Clínica de Ortodontia Dental Press, Maringá, v. 5, n. 3, pp. 48-75, 2006.

ALMEIDA-PEDRIN, R. R. et al. Treatment effects of headgear biteplane and bionator appliances. American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics, v. 132, n. 2, pp. 191 – 198, 2007.

ANDREWS, L. F. The six keys to normal occlusion. Am. J. Orthod., St. Louis, v. 62, n. 3, p. 296 – 309, 1972.

ANGLE, E. H. Treatment of malocclusion of the teeth. 7. ed. Philadelphia: S.S. White, 1907.

ARAUJO, P. P. Brandão., et al. Maloclusão uma questão de saúde pública. In: Dendasck, Carla Viana et al. (Orgs). Ciência da Saúde: Atualização de Área, p. 53 – 63, 2023.

ARAÚJO, E. A.; ARAÚJO, C. V. Abordagem clínica não – cirúrgica no tratamento da má oclusão de Classe III. Dental Press Ortodon Ortop Facial, v. 13, n. 6, pp. 128 – 157, 2008.

BACCETTI, T.; TOLLARO, I. A restropective comparison of functional appliance treatment of Class III malocclusions in the deciduous and mixed dentitions. Eur J Orthod, v. 20, n. 3, pp. 309 – 317,1998.

BIGLIAZZI, R. et al. Morphometric analysis of long – term dentoskeletal effects induced by treatment with Balters bionator. Angle Orthodontist, v. 3, pp. 790 – 798, 2015.

BOEK, E. et al. Prevalência de maloclusão em escolares de 5 a 12 anos de rede municipal de ensino de Araraquara. Rev. CEFAC, São Paulo, vol. 15, n.5, p. 1270 – 1280, 2013.

CARDOSO, M. A. et al. Metas terapêuticas para o tratamento ortodôntico-cirúrgico no Padrão III: relato de caso. 10.ed. Revista clínica de ortodontia dental press: Dental Press, v. 6, p. 60-70, 2011.

CARELS, C.; VAN DER LIDEN, P. M. G. Concepts on functional appliances mode of action. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop, v. 92, n. 2, pp. 162 – 168, 1987.

CARNEIRO, G. K. M. et al. Prevalência de maloclusões em crianças de 3 a 12 anos de idade no município de Mineiros–Goiás. Facit Business and Technology Journal, v. 1, n. 29, 2021.

CORLESS, I. B.; NICHOLAS, P. K.; NOKES, K. M. Issues in cross – cultural quality – of – life research. J Nurs Scholarsh, v. 33, n. 1, pp. 15-20, 2001.

DUTRA, S. R. et al. Impact of malocclusion on the quality of life of children aged 8 to 10 years. Dental Press J Orthod, v. 23, n.2, pp. 46-53, 2018.

FALTIN, K. J. et al. Long-term effectiveness and treatment timing for Bionator therapy. Angle Orthod, v. 73, n. 3, pp. 221-30, 2003.

FERES, R.; VASCONCELOS, M. H. F. Estudo comparativo entre análise facial subjetiva e a análise ceflométrica dos tecidos moles no diagnóstico ortodôntico. Dental Press Ortodon Ortop Facial, v.14, n. 2, pp. 81 – 88, 2009.

FERNANDES, D. A. A. et al. Prevalência Das Maloclusões Em Estudantes Das Redes Municipal E Estadual Do Município De Augusto Corrêa, Pará. Facit Business and Technology Journal, v. 1, n. 13, 2020.

FRANCHI, L.; BACCETTI T.; McNAMARA J. A. Postpuberal assesment of treatment timming for maxillary expansion and protraction therapy followed by fixes appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop, vol. 126, n. 5, pp. 555 – 568, 2004.

FREITAS, C. M.; FREITAS, R. R.; SILVA, J. R. C. Uso do Sistema Trainer no centro de especialidades odontológicas (CEO) de Ortodontia da ASCES (Caruaru-PE). Orthodontic Science and Practice: Plena, pp. 491-497, 2012.

GALLÃO, S. et al. Diagnóstico e tratamento precoce da Classe III: relato de caso. J Health Sci. v. 31, n. 1, pp. 104 – 108, 2013.

GANDINI JR, L.G. et al. Análise cafalométrica Padrão Unesp Araraquara. Dental Press ortodon Ortop Facial, v. 10, n. 1, pp. 139 – 157, 2005.

GERZSON, D. R. S.; NOBRE, D. F. Aplicações clínicas e vantagens da placa labioativa: uma revisão de literatura. Stomatos, Canoas, v. 17, n. 32, p. 97-104, 2011.

GIANCOTTI, A. et al. Pseudo – class III malocclusion treatment with Balters Bionator. Journal of Orthodontics, p. 203 – 215, 2002.

GODT, A. et al. Early treatment to correct Class III relations with or without face masks. Angle Orthod, v. 78, n. 1, p. 9 – 44, 2008.

GRANDO, G. et al. Prevalence of malocclusions in a young Brazilian population. IJO, v. 19, n. 2, p. 13 – 15, 2008.

JACOB, H.B. et al. Second molar impaction associated with lip bumper therapy. Dental Press Journal of Orthodontics, Maringá, v. 19, n. 6, p. 99-104, 2014.

LANDÁZURI, D. R. G. et al. Changes on facial profile in the mixed dentition, from natural growth and induced by Balters’ bionator appliance. Dental Press J Orthod, v. 18 n. 2 p.108-115, 2010.

LI, H.; MASOUD, A.; VOSS, L.R. Hybrid Hyrax/ quad – helix appliance in the phase I treatment of pseudo – Class III malocclusion. J. World Fed. Orthod. v. 2, p. 107 – 114, 2013.

LITTON, S. F. et al. A genetic study of class III malocclusion. Am. J. Orthod., v. 58, n. 6, p. 565-577, Dec. 1970.

MARTINS, L.P. et al. Má oclusão e vulnerabilidade social: estudo representativo de adolescentes de Belo Horizonte, Brasil. Ciência e Saúde Coletiva, v. 24, n. 2, pp. 393-400, 2019.

MORAIS, S.P.T. et al. Fatores associados a incidência de maloclusão na dentição decídua em crianças de uma coorte hospitalr pública do nordeste brasileiro. Bras. Saúde Matern. Infant, v. 14, n. 4, pp. 371- 382, 2014.

MOSS, M.L.; RANKOW, R.M. The role of the functional matrix in mandibular growth. Angle Orthod, v. 38, n. 2, pp. 95 – 103, 1968.

MOYERS, R.E. Ortodontia. 4. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan, 1991.

OLIVEIRA, C.M.; SHEIHAM, A. Orthodontic treatment and its impacto n oral health – related quality of life in Brazilian adolescents. J Orthod, v. 31, n. 1, pp. 7-20, 2004.

ORGANIZAÇÃO MUNDIAL DA SAÚDE, Levantamento epidemiológico em saúde bucal: manual de instruções. 4. ed. Genebra: OMS; 1997.

ORTOLANI-FALTIN, C.; FALTIN-JUNIOR, K. Bionator de Balters. Revista Dental Press de Ortodontia e Ortopedia Facial, v. 3, n. 6, pp. 70 – 95, 1998.

PIZZOL, K.E.D.C. et al. Tratamento de deglutição com pressão atípica do lábio com placa lábio-ativa reversa: relato de caso clínico. Jornal Brasileiro de Ortodontia e Ortopedia Facial, Curitiba, v. 9, n. 51, pp. 211-217, 2004.

RABIE, A. B. M.; GU, Y. Management of pseudo – class III malooclusion in southern Chinese children. Br Dental J, v. 117, n. 1, pp. 183 – 187, 2000.

RÉDUA, R. B. Different approaches to the treatment of skeletal Class II malocclusion during growth: Bionator versus extraoral appliances. Dental Press Journal Orthodontics, v. 25, n. 2, 2020.

RETAMOSO, L. B. et al. Ortodontia interceptativa no tratamento dos problemas de espaço. Ortodontia Gaúcha, Porto Alegre, v. 10, n. 1, pp. 79-86, 2006.

ROSSI, L. B. et al. Correction of functional anterior crossbite whith planas direct tracks: a case report. Revista da Faculdade de Odontologia de Lins/ Unimep., v. 22, n. 2, pp. 45-50, jan.jun. 2012.

SALLES, C. S. et al. Síndrome da apnéia e hipopnéia obstrutiva do sono: análise cefalométrica, v. 71, n. 3, pp. 369 – 372, 2005.

SB BRASIL 2010: Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde Bucal: resultados principais/ Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde. – Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 2012.

SCHULHOF R. J.; ENGEL G. A. Results of Class II functional appliance treatment. J Clin Orthod., Sep;16(9):587-99, 1982.

SIARA-OLDS, N. J. et al. Long – term dentoskeletal changes with the Bionator, Herbst, Twin Block and MARA functional appliances. Angle Orthod, v. 80, n. 1, pp. 18 – 29, 2010.

STUTZMANN, J. J.; PETROVIC, A.G. Results of class II functional appliance treatment. J. Clin Orthod, v. 16, n. 9, pp. 587 – 599, 1982.

SULIANO, A. A. et al. Prevalência de maloclusão e sua associação com alterações funcionais do sistema estomatognático entre escolares. Caderneta de Saúde Pública, v. 23, n. 8, pp. 1913 – 1923, 2007.

TERADA, H. H. Utilização do aparelho progênico para a correção das mordidas cruzadas anteriores. Ver. Dent. Press Ortodon. Ortop. Facial, v. 2, n.2, pp. 87 – 105, 1997.

TSAMTSOURIS, A.; VENDRENNE, D. The use of the Bionator appliances in the treatment of Class II, division 1 malooclusion in the late mixed dentition. J Pedodont, vol. 8, n. 1, pp. 78 – 100, 1983.

VALARELLI, F. P. Tratamento da má oclusão de Classe II por meio de aparelho regulador de função de Frankel. Revista Uningá, n. 40, pp. 119 – 133, 2014.

VELLINI, F. Ortodontia: Diagnóstico e planejamento clínico, 7ª ed. São Paulo, 2008.

[1] Dentistry Undergraduate Student. ORCID: 0009-0001-1734-8455. Currículo Lattes: http://lattes.cnpq.br/8709140095376311.

[2] Dentistry Undergraduate Student. ORCID: 0009-0003-8461-6338. Currículo Lattes: http://lattes.cnpq.br/1832010931426679.

[3] Dentistry Undergraduate Student. ORCID: 0009-0003-0477-2614. Currículo Lattes: http://lattes.cnpq.br/1977203311524825.

[4] Dentistry Undergraduate Student. ORCID: 0009-0001-8398-2390. Currículo Lattes: http://lattes.cnpq.br/7301946389987967.

[5] Supervisor. Update in Pediatric Dentistry, Qualification in Laser Therapy, Improvement in Orthodontics and Functional Jaw Orthopedics, Specialization in Public Health and Orthodontics, Master’s in Orthodontics, Ph.D. in Orthodontics. ORCID: 0000-0002-5514-0911. Currículo Lattes: http://lattes.cnpq.br/1678395879499706.

[6] Co-Supervisor. Ph.D. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4143-289X. Currículo Lattes: http://lattes.cnpq.br/4377698156424992.

Submitted: July 28, 2023.

Approved: August 10, 2023.