REVIEW ARTICLE

CARDOZO, Jorge Willian da Silva [1]

CARDOZO, Jorge Willian da Silva. Education of Brazilian entrepreneurs: an analysis of initial and established business owners. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. 04 year, Ed. 10, Vol. 10, pp. 129-138. October 2019. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link in: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/business-administration/entrepreneur-education

SUMMARY

Brazil has a large number of entrepreneurs who have the most varied levels of education. Some undertake out of necessity, while others for an observed opportunity. It is true that the motivation of these characters is not only marked by their level of education, however their level of training affects their way of seeing the world. The degree of training of the individual has great influence on the management of the business and the proportion of entrepreneurs in each level has been changing over the years. Understanding the role of education in the scope of management and its consequences is the object of study of governmental entities and the academic community. The number of entrepreneurs in Brazil has increased in recent years and the level of education has also been changing. This instance understands the role and due interest of the State in the compulsory education of the entrepreneurial population, since the reflections of its actions impact the success of business in the country generating income, employment, economic/technological development and tax collection for its activities. It is remarkable that there is also a concern with the formation of the entrepreneur, not at this time addressing his traditional education (elementary, secondary and higher education), but the development of skills, techniques and knowledge specific to the performance of its manager role. More than two-fifths of adults with incomplete primary education are entrepreneurs, while only thirty percent of those with higher education or higher education are in the same condition. This work seeks to identify how the profile of the entrepreneur, according to the level of education, has been moving in Brazil over the years and how this can affect the success of the business and the way of facing difficulties. The diversity of these individuals regarding gender and the time they are at the forefront of their business is also considered, thus observing the entrepreneur’s education in the various faces of the Brazilian scenario.

Keywords: Entrepreneurship, entrepreneur education, professional training.

1. INTRODUCTION

Understanding how the level of education influences the management of entrepreneurs is a relevant and current theme in the current Brazilian scenario in which knowledge management becomes a strong competitive strategy. Investigating whether there is a direct relationship with the success of the business to the quantity and quality of training is a theme that motivated the existence of several scientific works.

According to data from The Continuous PNAD (2018), the percentage of entrepreneurs on their own jumped from 22.8% in 2012 to 25.3% in 2017 among the total staff employed in Brazil. In the same period the number of employers jumped from 4% to 4.6%. (IBGE 2018a). On the other hand, more than half of Brazilians over 25 years of age do not even have a complete high school level. (IBGE, 2018b)

Pereira (2001, p. 1) says that “venturing into the unusual business world without the necessary qualification can be and has been disastrous.” In this context, qualification is understood as a necessary factor for survival in the competitive scenario.

This work does not specifically deal with the teaching of entrepreneurship, but the level of education of the entrepreneur in general. It is true that the teaching of the subject of management and entrepreneurship contributes to the assertiveness of entrepreneurs. However, the relationship between the individual’s educational level and the results of his/her way of managing, or, how long-live and healthy his results are, is what guide the elaboration of this work.

2. METHODOLOGY

This work was developed through the review of scientific articles and books. Based on the Report of the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2018, GEM, effects from the difference in the level of education of entrepreneurs were identified. In this core, we sought to identify how much the level of education impacts the difficulties of managing a business from the perception of the entrepreneur himself and how this can be transformed.

It was also investigated how long these businesses are according to the level of education and in which layer the majority is: initial or established. In view of this, several studies are analyzed that deal with this relationship between an individual’s level of education and entrepreneurship.

3. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

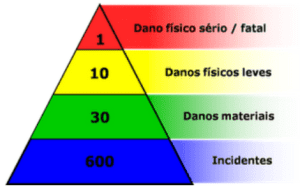

According to the report of the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM, 2018), in Brazil, 14.6 million entrepreneurs did not even have completed elementary school, but they belong to the highest rate of established entrepreneurs.

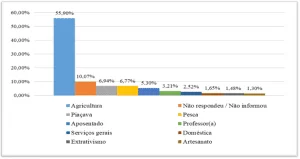

It is necessary to clarify the difference between the initial entrepreneurs and the established entrepreneurs. Substantially, GEM brings two groups of early entrepreneurs: the springs and the new ones. The springs are those entrepreneurs who are involved in a new business that has not yet paid any remuneration to its owner for more than three months. The group of new entrepreneurs contains those businesses that have already paid some remuneration to their owners for a period of more than three months and less than 42 months. And the last group, of established entrepreneurs, comprises those businesses considered consolidated for having already paid their owners some remuneration for a period of more than 42 months. (GEM, 2018)

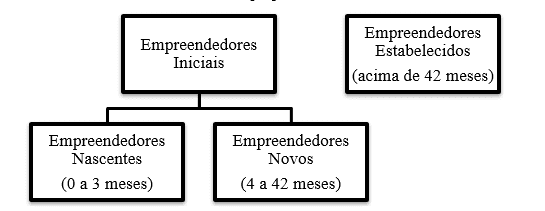

Figure 1. Initial entrepreneurs x Established by time of remuneration paid to their owners.

GEM (2018) shows that there is a difference in relation to the entrepreneurial activity in the initial and established stage. Among the highest levels of those who are in the early stages, the most active are those who have only completed elementary school, while the least active are those with complete higher education. In relation to the entrepreneurial activity in an established stage, those with incomplete elementary education are the most active, while the less active have completed elementary school.

Graph 1 shows that the lower the level of education, the greater the chance of this individual being an entrepreneur in Brazil.

Gráfico 1. Rates (in %) number of entrepreneurs by level of education2 according to stages of enterprise – Brazil – 20173

1 Percentage of the population referring to each population category (e.g. 19.6% of those who have incomplete Elementary School in Brazil are early entrepreneurs).

2 Incomplete elementary school = No formal education and incomplete elementary school; Complete elementary school = Complete elementary school and incomplete high school; Complete high school = complete high school and incomplete higher education; Complete or major higher education = complete superior, complete and incomplete specialization, complete and incomplete master’s degree, incomplete doctorate and complete doctorate.

3 Estimates calculated from data from the Brazilian population aged 18 to 64 years for Brazil in 2017: 135.4 million

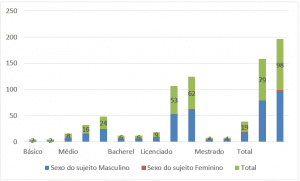

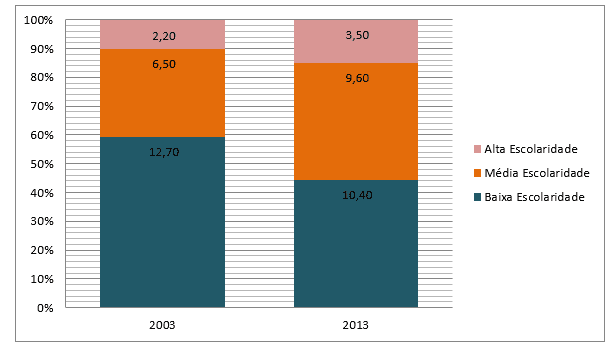

Considering the period from 2003 to 2013 “the relative participation of those with high education went from 10% to 15%, that of those with average education increased from 30% to 41%, and of those with low schooling fell from 59% to 44% of the total.” (Bedê, 2015, p. 9)

In Graph 2 it is possible to visualize this shrinkage of those with low schooling and an increase of those with medium and high.

Graph 2. Participation of entrepreneurs according to schooling (in millions)

From Meza et al. (2008) makes an important approach in his work saying that Latin American countries with the greatest potential for innovation have high rates of education. Although this approach deviates somewhat from the micro purpose of this work, it is important to realize how tied schooling is to the results obtained in business.

Pereira (2001, p. 12) says that “being an entrepreneur or not is not a matter of simple freedom, of a choice. The profile of the entrepreneur must contain the appropriate way to the uncertain and challenging environment of today.”

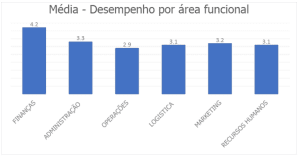

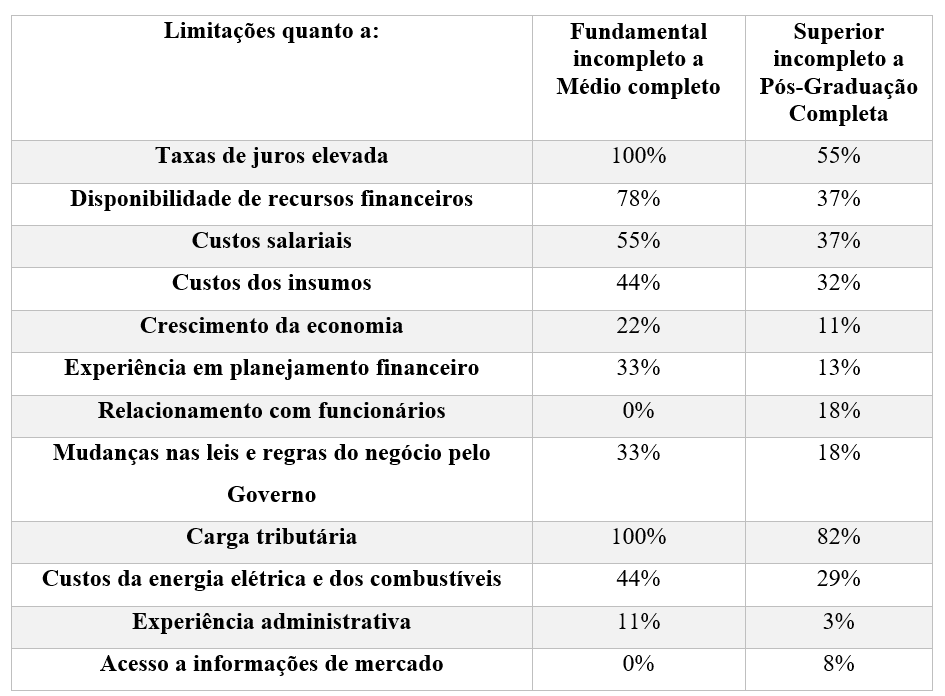

A study by Romano Carrão et al. (2013) shows the difference in the perception of the difficulties encountered in the management of a business according to the level of education. It is worth mentioning that in this work in question, the division is made between entrepreneurs with incomplete elementary to complete medium and incomplete higher education to complete graduate studies.

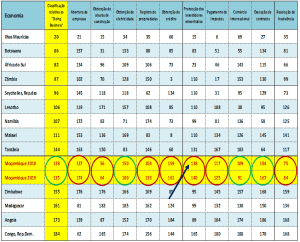

Table 1. The influence of education on the view of the small business owner

This sample presented in the research by Romano Carrão et al. (2013) demonstrates that when the entrepreneur has a higher level of education, he faces with less difficulty several points that imply the management of a business, especially when it comes to the financial and tax issue. However, it is noted that entrepreneurs with less schooling have less difficulty in the relationship with employees.

According to Barbosa and Teixeira (2001, p. 22) “an improvement in the level of education would lead to an improvement in the economic level of a given locality, the development of the company and its human resources.”

It is important to bring to light a small difference in the agenda with regard to genres. According to GEM (2018), the majority of early stage entrepreneurs are female (14.2 million are women and 13.3 million are men). However, within the stage of established entrepreneurs this is reversed (12.5 million are men and 9.9 million are women). Naatividade (2009) in his study on female entrepreneurship in Brazil realized from the GEM reports from 2002 to 2006 that:

When analyzing schooling, it is perceived that, over the five years, the small range of entrepreneurs with schooling above 11 years of schooling is among those motivated by opportunity, while half of the projects created represents an initiative of individuals with one to four years in formal education, characterized mainly by entrepreneurs by necessity. (NAATIVIDADE, 2009, p. 238)

4. RESULT

The GEM report (2018) brings five recommendations from experts to improve the conditions for entrepreneurship in Brazil regarding Education:

-

-

- Investment in training and mentoring, that is, government programs that finance knowledge assets, not just structures;

- Support institutions that already promote entrepreneurship (Sebrae, Endeavor, Senac, etc.), integrating them into a structured project;

- Encouraging entrepreneurship in mass media: sharing experiences and cases of success and failure through television programs, advertisements, among others;

- The approximation of entrepreneurial activity intuitively practiced with school environments, with the university, such as academia. This is fundamental for the qualification of entrepreneurship in Brazil. The same goes for the approximation between research and good technologies with those who are interested in opening a new business.

- The insertion of entrepreneurial education from elementary school. The sooner the entrepreneurial spirit is disseminated, the greater the chance of having young entrepreneurs in the future, with a good lack of knowledge about business plan, market study, economic factors that affect the business, among other aspects essential to succeed. (GEM, 2018, p. 19)

-

Regarding the promotion of entrepreneurship at the educational level, Santos (2012, p. 43) says that “despite the presence of universities in the offer of courses with emphasis on promoting entrepreneurship, one perceives the need to identify which priorities and principles that should underpin this formation.” That is, it is not enough just to insert the theme of entrepreneurship within universities without there being a mapping of the latent needs of the context and the definition of goals and objectives.

Entrepreneurship teaching should not be limited to the classroom or formal learning structures. SME employees and employees should seek to improve their entrepreneurial skills through interactions with their co-workers, suppliers, clients and consultants. (SANTOS, 2012, p. 43)

According to Barbosa e Teixeira (2001, p. 23) “the need for recycling and acquisition of new knowledge is constant for those who dedicate themselves to the business world.” From this point, it is observed that schooling is not unilaterally determining the future of the entrepreneur when analyzed in isolation. The training of this entrepreneur for the management of his economic activity also has great value, not only the amount of years in the classroom is solely decisive for his success.

Entrepreneurship programs, with techniques that aim to train the entrepreneur, generate business incubators, entrepreneurship disciplines in universities, undergraduate in the area, junior companies, etc. The goal of such initiatives has been to equip people with knowledge, in order to increase the chances of survival and success of their own business. (PEREIRA, 2001, p. 11)

From the work of Barbosa and Teixeira (2001) it is possible to understand that entrepreneurial education promotes, albeit indirectly, the emergence of new businesses, the maintenance of existing ones, and local economic development.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In this study, it was possible to see that the number of entrepreneurs with low schooling has decreased absolutely and relatively in view of the increase in entrepreneurs with medium and high schooling. However, it also points out that the rate of established entrepreneurs is higher among those with lower education, that is, the incomplete elementary level. From the review of the theme, it is inferred that this is due, among other factors, mainly to entrepreneurs due to the need to come from an environment with a high unemployment rate, the latter that greatly affects those with low schooling, given that the little training makes it difficult for them to enter the labour market as employees.

It is important to remember that in the age of knowledge, intellectual capital is the largest investment of a company (MACHADO, 2005). Chiavenato (2012) reinforces this by stating that knowledge is the most important resource, even more than money.

Although this work has focused on the figure of the entrepreneur and his level of education, we envision the opportunity to maintain the investigation of this theme in the coming years with the objective of monitoring the movement that occurs in Brazil. As it is already known that proportionally the number of entrepreneurs with low schooling has been decreasing and that this group is more likely to be an entrepreneur in Brazil, following the movement of Brazilian education and general levels of unemployment (which stimulate the entrepreneurship by necessity) is essential for the decision-making of government entities and the development of scientific material for study and follow-up.

6. REFERENCES

BEDÊ, Marco Aurélio (Coord.). Os donos de negócio no Brasil: análise por faixa de escolaridade (2003-2013). Brasília: SEBRAE, 2015. [Série Estudos e Pesquisas].

BARBOSA, Jenny Dantas; TEIXEIRA, Rivanda Meira. Apesar dos pesares, vale a pena ser pequeno empresário? Traçando perfil e descobrindo motivos. Encontro de Estudos sobre Empreendedorismo e Gestão de Pequenas Empresas. Londrina. Anais. Londrina: Universidade Estadual de Londrina, p. 14-30, 2001.

CHIAVENATO, Idalberto. Administração Geral e Pública. 3ª ed. Barueri: Manole, 2012.

DE MEZA, Maria Lucia Figueiredo Gomes et al. O perfil do empreendedorismo nos países latino-americanos na perspectiva da capacidade de inovação. Revista da Micro e Pequena Empresa, v. 2, n. 3, p. 58, 2008.

GEM – Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. Empreendedorismo no Brasil: 2017. Curitiba: IBQP, 2018.

INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFIA E ESTATÍSTICA. Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios Contínua: Características adicionais do Mercado de Trabalho: 2012-2017. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE, 2018a.

INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFIA E ESTATÍSTICA. Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios Contínua: Educação: 2017. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE, 2018b.

MACHADO, J. R. A Arte de Administrar Pequenos Negócios. 2 ed. Rio de Janeiro: Qualitymark, 2005.

NATIVIDADE, Daise Rosas da. Empreendedorismo feminino no Brasil: políticas públicas sob análise. Revista de Administração Pública, v. 43, n. 1, p. 231-256, 2009.

PEREIRA, Sonia Maria et al. A formação do empreendedor. Tese (Tese em Engenharia de Produção) – Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. Florianópolis: 2001.

ROMANO CARRÃO, Ana Maria; JOHNSON, Grace Florence; DE LIMA MONTEBELO, Maria Imaculada. A influência do grau de escolaridade do pequeno empresário sobre sua percepção de negócio. Revista Eletrônica de Administração, [S.l.], v. 13, n. 2, p. 409-432, maio 2013. ISSN 1413-2311.

SANTOS, Carlos Alberto. Pequenos negócios: desafios e perspectivas–inovação. Brasília: Sebrae, 2012.

[1] Specialist in Planning, Implementation and Management of EaD by UFF (Niterói /RJ); Marketing Specialist at Ucam (Rio de Janeiro/RJ); Bachelor of Business Administration from Unifeso (Teresópolis/RJ).

Posted: September, 2019.

Approved: October, 2019.