ORIGINAL ARTICLE

SILVA, Carlos Marcelo Faustino da [1], MORAIS, Léa Paula Vanessa Xavier Corrêa de [2]

SILVA, Carlos Marcelo Faustino da. MORAIS, Léa Paula Vanessa Xavier Corrêa de. Diagnosis and proposal of intervention of Knowledge Management practices: Case study in the active incubator of companies of the Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of Mato Grosso. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 05, Ed. 10, Vol. 05, pp. 16-50. October 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/business-administration/diagnosis-and-proposal

SUMMARY

With the premise that the environment of entrepreneurship and innovation of incubators has its results optimized when there is an efficient management of the creation, transfer, flow and application of knowledge, this research aimed to carry out a case study of the Active Business Incubator of IFMT to diagnose how it was in relation to knowledge management practices and elaborate intervention proposals according to the result. A questionnaire was applied to the Executive Management in the incubator, as well as in its nuclei that were constituted throughout the state of Mato Grosso in 2019. It was noticed that although most managers of the centers were not familiar with this type of management, there is a comprehensive perception of the practices, however, in a little intensified and very lame way in some cases, such as individual skills banking practices, organizational skills bank and competency management system. As an intervention proposal, it was suggested to use practices that already work related to the transfer of knowledge to socialization between nuclei that already have an effective implementation and that generate results and those that are still out of date.

Keywords: Incubator, entrepreneurship, innovation, knowledge management.

1. INTRODUCTION

With the constant evolution of the contexts in which humanity and the increasing flow of information are included, it can be affirmed that transformations in society are and will always be constant. Currently much is said about the Knowledge Society, a term that reaching the end of the 1990s ended up overlapping the Information Society, since now the focus is expanded information for the process of this information by the human being (STRAUHS et. al., 2012).

In this context of rapid evolution that affects several spheres, knowledge becomes a primordial factor since with large and continuous social, economic, political and cultural transformations and the search for ways to follow the trends of these transformations, knowledge has become the greatest generator of wealth and the most important factor of production (MAGNANI and HEBERLÊ, 2010).

It is notepoint that the concept of knowledge is tied to the result of the interpretation of information and its use for some purpose, that is, the use of information in order to answer a question that seeks resolutions or even assists in decision making, so creating knowledge goes beyond the generation of data and information, reaching forms of representations that provide meaning and context for objective actions (PIMENTA and NETO , 2008).

Taking into account the relevance of knowledge, Strauhs et. al. (2012) place as fundamental the role of education and social relations because knowledge creation environments need much more than technology, with the indispensability of the participation of people capable of being permanently sharing ideas.

In this aspect, it is clear the importance of managing knowledge, as presented by Magnani and Heberê (2010) when they state that this type of management is the recognition that information and knowledge are corporate assets with great potential to optimize results and that they need to be properly understood and managed, thus, through specific tools for their nature.

The authors also point out that both private and public organizations in any sector are inserted in a globalized context of intense competitiveness, so they need to work on administrative skills and improve their respective management tools (MAGNANI and HERBERÊ, 2010).

Therefore, even though Knowledge Management (GC) is a more widespread concept in the environment of private companies, it is necessary to be attention to its practice in the public area, since to the extent that public organizations are transformed into institutions focused on knowledge, knowledge can become one of its main allies (BATISTA, 2012).

Magnani and Herberê (2010) reinforce the idea that the GC should also cover the public area when iteating that there are significant benefits for the government sector when adopting knowledge management strategies, especially for those organizations in which it is the human factor that holds knowledge of critical and strategic importance for their future actions, which is the case of organizations that work intensively with Research , Development and Innovation – R&I, where the structure of knowledge is essential.

That is, in a general aspect, GC is considered an important method to mobilize knowledge in order to fulfill a organization’s strategic objectives and improve its performance (BATISTA, 2012).

Thus, taking into account that we live this moment guided by the relevance of knowledge where, consequently, innovation is a fundamental part of the economic and social development of our society (FURLANI, 2018), the perspective of GC study arises in the context of business incubators, since these environments should not have their role summarized the simple creation of companies, because among its various purposes is also monitoring to stimulate the innovation process promoting opportunities for development and granting, in addition to physical space, administrative support, advice and consulting of various areas (BAÊTA, 1999 apud BEUREN and RAUPP, 2003).

Thus, because they work in environments focused on innovation, where more active postures are needed in relation to the organizational knowledge used, there is the premise that individuals already perform in these spaces some practices and characteristic actions for a GC that occurs in a comprehensive and effective way (MÜLLER et. al., 2015).

Thus, with this important function of managing businesses assigned to incubators, the problem of this study of measuring how much the Active Business Incubator of the Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of Mato Grosso has followed the evolution of the Knowledge Society and developed in its practical activities of GC in order to improve its internal environment and make it more conducive not only to better management but also to the creation of innovation itself. For this purpose, it was considered as a basis for obtaining the data for analysis, mainly, the measuring instrument provided in the publication “The challenge of Knowledge Management in the areas of administration and planning of federal institutions of higher education (IFES)” whose objective is to disseminate results of studies directly or indirectly developed by the Institute of Applied Economic Research (Ipea), where the author analyzed the current situation of the implementation of knowledge management practices in 45 institutions.

2. THEORETICAL FOUNDATION

2.1 KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT PRACTICES

Before delving into the concepts of GC, it is necessary to establish the constitution of knowledge itself, which differs in the literature from the area of the concept of data and information. Setzer (2014, not paged) brings in his study that:

A data is purely objective – it does not depend on your user. The information is objective-subjective in the sense that it is described in an objective way (texts, figures, etc.). or captured from something objective, as in the example of extending the arm out of the window to see if it is cold, but its meaning is subjective, dependent on the user. Knowledge is purely subjective – everyone has the experience of something in a different way.

Thus, knowledge is linked to its bearer as a representation of the sum of a person’s experiences and/or organization, establishing that this concept refers to something that exists in the human mind and requires analysis, synthesis, reflection and contextualization (ALVARENGA NETO, 2005).

There is consensus among the various scholars that knowledge resides in the intellectual capital of people who come from the result of human experience and their reflections, based on beliefs and experiences that are both individual and collective. This makes professionals become decisive assets for the success of their organizations, since, in contemporary management, it is intangible assets, constituted by knowledge, that triumph. (MAGNANI e HERBELÊ, 2010).

The importance of knowledge is also reinforced by Probst et. al. (2012, p. 16) when they reiterate that “If a company with a well-developed knowledge base operates in a knowledge-intensive environment, it is likely that its specific skills will develop its own dynamics, thus creating new strategic opportunities.”

In this context, the importance of GC arises as established by Strauhs et. Al. (2012, p. 55) when they state that this management model comes to “[…] provide conditions to create, acquire, organize and process strategic information and thus generate benefits […]”. According to the authors more than just creating knowledge, managers should seek to turn them into practical results.

Thus, the GC is intrinsically linked to how the knowledge held in the people who make up the organization can be managed to bring answers to resolutions of situations that involve the general aspect in which they are inserted, and it is important to highlight that, as evidenced by Magnani and Heberlê (2010), the GC is not directly linked to the need for implementation of information technology systems , but of training processes for the production of knowledge.

Strauhs et. al. (2012) present that within knowledge management two different concepts are dealt with, tactical and explicit knowledge, and tacit is the one that is individual, often unmanageable, and that becomes public, that is, explicit, by means of conversion processes widely discussed academically.

Magnani and Heberlê (2010) bring us that the construction of tacit knowledge, that is, the one that is individual, is directly linked to the experience of the individual. According to the authors:

The secret to acquiring tacit knowledge is experience. Without some form of shared experience it is extremely difficult for a person to project themselves into another individual’s reasoning process. Mere transfer of information makes no sense if it is disconnected from the associated emotions and the specific contexts in which shared experiences refer. Therefore, the socialization process is essential to outsource and transfer tacit knowledge (MAGNANI and HEBERLÊ, 2010, p. 78).

Thus, for tacit knowledge to be reached by an individual, it is indispensable that he participates in some practical experience for the construction of that knowledge, that is, so that he can learn by application. Strauhs et. al. (2012, p. 37) reinforce the importance of tacit knowledge management by stating that:

Collaborators with the ability to improve tacit knowledge also increase their process of explanation, that is, their ability to share their own knowledge with other individuals, because they understand that sharing grows not only the organizational environment but also its own universe, in a vicious cycle.

The authors Takeuchi and Nonaka (2008 apud MÜLLER et. al., 2015) present a model that seeks the conversion of tacit knowledge of individuals to explicit knowledge through the SECI process, which contains the stages of Socialization, Outsourcing, Combination and Internalization of knowledge. Being:

a) Socialization: sharing and creation of tacit knowledge through direct experience that an individual acquires from an individual, that is, from tacit knowledge to tacit knowledge;

b) Outsourcing: articulation of tacit knowledge through dialogue and reflection, that is, it does not have the experience character. Outsourcing occurs from individual to group, from tacit to explicit knowledge;

c) Combination: systematization and application of knowledge and information, occurring from a group of people to the organization, with a defined objective. The combination is made of explicit knowledge for explicit knowledge;

d) Internalization: learning and acquisition of new tacit knowledge from organizational practice, that is, internalization occurs from organization to individual and is made of explicit knowledge for tacit knowledge.

Thus, it is important that knowledge take a cycle within the organization, to ensure that its creation and dissemination are continuously generating positive effects. Strauhs et. Al. (2012) state that the environment is a decisive factor for stimulating knowledge sharing, especially when it points out that:

In addition to being permeated by trust, the environment conducive to knowledge must be stimulated by the belief that the sharing of knowledge allows its exponential growth. This environment must also rely on informational technologies that allow individuals to connect to the world around them and also to management policies that depend on people being adept or not to the continuous construction of knowledge (STRAUHS et. al., 2012, p. 52).

Regarding informational and practical technologies aimed at the proper functioning of the GC, Table 1 presents a list of 22 GC practices that was elaborated from concrete examples observed in organizations around the world, encompassing practical, technical, process and tools applications, adapted from the publication “The Challenge of knowledge management in the areas of administration and planning of federal Institutions of Higher Education (IFES)” :

Table 1 – Knowledge management practices in the areas of planning and administration

| Action or Practice | Definition |

| Workflow systems | Quality control of information supported by the automation of the flow or the process of documents. Workflow is the term used to describe the automation of systems and internal control processes, implemented to simplify and expedite the establishment of partnerships, agreements, contracts involving financial resources or not. It is used for document and revision control, payment requests, employee performance statistics, etc. |

| Best practices | Identification and dissemination of best practices, which can be defined as a validated procedure for performing a task or for solving a problem. Includes the context in which it can be applied. They are documented through databases, manuals, or guidelines. |

| Data warehouse (IT tool for GC support) | Data tracking technology with hierarchical architecture arranged in relational bases, which allows versatility in the manipulation of large masses of data. |

| Data mining (IT tool for GC support) | Data miners are instruments with high ability to association terms, allowing them to “pan” specific subjects or themes. |

| Communities of practice/knowledge communities | Formal and interdisciplinary groups of people united around a common interest. Communities are self-organized in such a way as to allow the collaboration of people inside or outside the organization; provide the vehicle and context to facilitate the transfer of best practices and access to specialists, as well as the re-use of models, knowledge and lessons learned. |

| Mentoring | Performance management modality in which a participant expert (mentor) models the competencies of an individual or group, observes and analyzes performance, and feeds back the execution of the activities of the individual or group. |

| Coaching | Similar to mentoring, but the coach does not participate in the execution of activities. It is part of a planned process of guidance, support, dialogue and monitoring, aligned with the strategic guidelines. |

| Internal and external benchmarking | Systematic search for the best references for comparison to the processes, products and services of the organization. |

| Forums (face-to-face and virtual) /mailing lists | Spaces to discuss, homogenize and share information, ideas and experiences that will contribute to the development of skills and to the improvement of processes and activities of the institution. |

| Knowledge mapping or auditing | Registration of organizational knowledge about processes, products, services and relationship with customers. It includes the elaboration of maps or knowledge trees, describing flows and relationships of individuals, groups or the organization as a whole. |

| Collaboration tools such as portals, intranets, and extranets | Portal or other computerized systems that capture and spread knowledge and experience among workers/departments. A portal is a web space for the integration of corporate systems, with data security and privacy. The portal can be a true work environment and knowledge repository for the organization and its employees, providing access to all relevant information and applications, as well as a platform for communities of practice, knowledge networks and best practices. In the more advanced stages allows customization and customization of the interface for each of the servers. |

| Competence management system | Management strategy based on the competencies required for the exercise of the activities of a given workplace. The practices in this area aim to determine the competencies essential to the organization, to evaluate the internal capacity in relation to the domains corresponding to these competencies and to define the knowledge and skills necessary to overcome the existing deficiencies in relation to the level desired for the organization. They may include mapping key processes, key competencies associated with them, existing and necessary tasks, activities and skills, as well as measures to overcome deficiencies. |

| Individual skills bank/yellow pages talent bank | Repository of information on people’s technical, scientific, artistic and cultural capacity. The simplest form is an online list of staff, with a profile of each user’s experience and areas of expertise. The profile may be limited to the knowledge obtained through formal education and training and improvement events recognized by the institution, or it can map, more broadly, the competence of employees, including information on tacit knowledge, experiences and business and procedural skills. |

| Organizational skills bank | Repository of information on the location of knowledge in the institution, including sources of consultation and also the people or teams holding a certain knowledge. |

| Organizational memory/lessons learned/knowledge bank | Registration of organizational knowledge about processes, products, services and relationship with users. The lessons learned are reports of experiences in which what happened, what was expected to happen, the analysis of the causes of differences and what was learned during the process. Content management keeps up-to-date information, ideas, experiences, lessons learned, and best practices documented in the knowledge base. |

| Organizational/business intelligence/competitive intelligence systems | Transformation of data into intelligence in order to support decision making. They aim to extract intelligence from information, through the capture and conversion of information into various formats, and to extract knowledge from information. Knowledge obtained from internal or external sources, formal or formal, is formalized, documented and stored to facilitate its access. |

| Corporate education | Continuing education processes established with a view to updating staff uniformly in areas of the institution. It can be implemented in the form of corporate university, distance learning systems, etc. |

| Corporate University | Formal establishment of an organizational unit dedicated to promoting the active and continuous learning of the organization’s employees. Continuing education programs, lectures and technical courses aim to develop both broader behaviors, attitudes, and knowledge as well as more specific technical skills. |

| Management of intellectual capital/management of intangible assets | Intangible assets are resources available in the institutional environment, difficult to qualify and measure, but contribute to their productive and social processes. The practice may include mapping of intangible organizational assets, human capital management, intellectual property policy. |

| Narratives | Techniques used in knowledge management environments to describe complicated subjects, expose situations and/or communicate lessons learned, or even interpret cultural changes. These are retrospective reports of personnel involved in the events that occurred. |

| Content management | Representation of the processes of selection, capture, classification, indexing, registration and debugging of information. It typically involves continuous research of content arranged in instruments such as database, knowledge trees, human networks, etc. |

| Electronic Document Management (GED) | Management practice that implies the adoption of computerized applications of emission control, editing and monitoring of the processing, distribution, archiving and disposal of documents. |

Source: adapted from Batista, 2006 in “The Challenge of knowledge management in the areas of administration and planning of federal Institutions of Higher Education (IFES)”.

Thus, it is understood that the institutions that adopt these practices in their daily lives contribute to a good flow of knowledge among their employees, while covering the processes of creation, transfer and application of knowledge, thus ensuring to enjoy the benefits offered by the GC within organizations, such as better management of internal processes and intensification of innovative processes.

2.2 KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT IN PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION

In the 21st century, the globalized knowledge economy brings new demands that change both the prospects of business management and those of government of countries and cities (WIIG, 2011). We live in a world of rapid and constant change guided by globalization, where a knowledge-based economy brings not only challenges, but also opportunities, both for the private and public areas, so that it can be affirmed that an effective acquisition and dissemination of knowledge are, above all, strong factors for the proper functioning of government functions (CONG and PANDYA , 2003).

For these opportunities to be taken advantage of, it is necessary to seek the integration and creation of a participatory culture in the organization, where each and every one is interested in collaborating to create an environment conducive to innovation and continuous learning, seeking and spreading the character of knowledge not only for the benefit of the organization, but also for the professional growth of people linked to this process (FIGUEIREDO , 2005 apud LIMA et. al. 2014).

The public administration, in general, has the responsibility to ensure that the area over its scope will always have the ability to not only maintain but improve the quality of life it intends to offer its citizens, this means, among other factors, maintaining the workforce of that region competitive enough to be able to complete itself in the regional and also global economy. These situations are well known by public administrators, and it is in this context that the field of knowledge management introduces new options, capabilities and practices that can impact and help the public administration to obtain advantages, so it also becomes a new responsibility of the public administration to manage knowledge capable of strengthening the effectiveness of public services and improving the experience of society (WIIG , 2000).

Moreover, when one thinks of the CG as a form of approach inserted in the internal context of a public agency, Batista (2012, p. 43) brings the importance of his practices by emphasizing that this management can be used “[…] to increase organizational capacity and achieve excellence in public management through the improvement of internal processes, development of essential competencies and planning of innovative strategies.” Thus, it can be affirmed that, in public administration, an effective GC helps in coping with challenges and resolutions of situations by implementing innovative management practices and improving the quality of public service for the benefit of citizens, who are its users, and thus society as a whole (BATISTA, 2012).

In question of the applicability of the GC it is necessary to emphasize that the people involved play an important role, so the public organization should invest in training and career development in order to increase the ability of servers and public managers to identify, create, store and apply knowledge. Considering that the set of individual capabilities of a team’s public servants is what contributes to increasing the capacity of the team as a whole, it can be affirmed that when a team’s servers are constantly learning and sharing knowledge among them, there is an increase in the ability to perform the work team (BATISTA, 2012).

In his study on the GC at the Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of Maranhão, Lima et. al (2014, p. 107) bring the institution as a relevant object of study, since:

The Federal Institute, as an educational institution, produces knowledge daily, which despite its importance is often lost in bureaucracy, and in the midst of the era of information technology, it has been observed that the appropriate knowledge by the servers, is weakened, in the face of this new context that presents itself. In this context, the challenge of producing more and better, as well as the challenge of providing a quality service to the population is being supplanted by the permanent challenge of creating new products, services, processes and management systems.

Thus, it can be affirmed that despite all its context involved in the business environment of private institutions, knowledge management has the potential to be a fundamental ally for the sectors of the public area, because its practices are capable of generating internal benefits in several areas that will positively affect the final result, which is to offer quality of public products and services to society.

2.3 KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT IN INCUBATORS

A business incubator can be defined as an environment that aims to support entrepreneurs so that they can develop innovative ideas, usually in early stages, and transform them into enterprises ready to enter the market, for this, it offers infrastructure and management support, guiding entrepreneurs in business management and its competitiveness (ANPROTEC, 2019).

Depiné and Teixeira (2018) present in their book “Innovation Habitats: concept and practice” a study about the relevance of incubators from the point of view of several authors, bringing them as one of the main habitats of innovation, because they are able to provide the necessary conditions and facilities for the emergence and growth of new companies and businesses, leveraging economic factors and the development of entrepreneurial culture in the conjuncture in which they are inserted.

Currently many educational institutions have adopted the link to these innovation environments in order to leverage the projects of their students and stimulate them in the practice of entrepreneurship, this is feasible from the moment that it is considered that this type of institution has a certain responsibility in the creation of knowledge, which is reiterated by Martins et. al. (2006, p. 1) when they point out that:

They are incubators that house enterprise for which knowledge is the main insum and that sell products with high added value. This type of incubator is preferably located near universities or research centers. Thus, they can take advantage of the highly specialized workforce and, in a timely manner, can awaken the entrepreneurial spirit in the students and researchers of these entities.

Thus, the importance of incubators linked to educational institutions stands out, since, as Fiala and Andreassi (2013, p. 760), “In the search for new methodologies and elements for teaching and stimulating entrepreneurship, business incubators appear as an environment that could be explored more intensely for this purpose”.

The importance of incubators is intrinsically linked to the development of the economy from which they are located, since the stimulus to entrepreneurship also adds incentives in areas of this sector. This is corroborated by Silva (2009, p. 246) when he states that:

Incubators contribute to the promotion of entrepreneurship, economic-regional development, job creation, technological development and economic-regional diversification, offering innovative products and services. Its main stimulators believe that they are an intelligent and appropriate option to promote local and national socioeconomic development. They therefore provide two motivations of different natures: economic and social.

Therefore, it can be affirmed that business incubators are already part of the entrepreneurial daily life and in their activities deal with organizations and complex environments, focused on innovation and with strong use of knowledge as raw material of their processes, products and services. (MÜLLER et. al., 2015).

Therefore, understanding the relevance of incubators and also their role in the creation of knowledge through the need to be innovative, one enters the context of knowledge management within these environments, especially, so that knowledge can reach the people involved in the enterprises of which these incubators are responsible. Raupp (2010, p. 193) confirms this view by bringing that:

Because it is an environment where knowledge is generated, incubator managers need to channel them, through entrepreneurs, so that they can be disseminated and developed through new business units.

Thus, it is considered that the GC and its practices of developing solutions and innovations can contribute significantly when applied in the context of business incubators, not only in the way it manages its internal processes, but also in the construction and dissemination of knowledge to its community.

2.4 THE ATIVA INCUBADORA IFMT BUSINESS

Ativa Incubator is a program offered by IFMT for traditional or supportive entrepreneurs who wish to develop innovative products or services, with technical, managerial, physical and technological support from IFMT and partner institutions, in order to make them innovative and sustainable ventures. Its incubation and performance area was initially focused on IFMT campus São Vicente and now meets with management in the rectory and with nuclei present in various campuses of the state, going through restructuring planning to enable its performance in all, contributing in the promotion of regional development. (IFMT, 2019)

On 04/28/2015, according to CONSUP Resolution No. 06 of 04/28/2015, Ativa had its management inserted in the activities of the Axis: Entrepreneurship of the Pro-Rectory of Extension, having expanded its objectives and enhanced its performance, and today is defined as a “Program linked to the Pro-Rectory of Extension, created with the objective of promoting innovative ventures, offering support to entrepreneurs so that they can develop innovative ideas and transform them into successful ventures.” (IFMT, 2019).

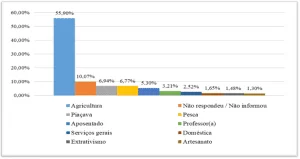

Thus, Ativa Incubadora today has its Executive Management located in the rectory of the institute, in Cuiabá, but its performance includes several regions of the state through the local centers that can be opened in each campus. Image 1 taken from the Ativa Incubadora website demonstrates the layout of the nuclei currently in the state:

Image 1 – The Ativa Incubadora IFMTBusiness

As shown in Image 1, Ativa in 2019 was spread in 9 nuclei throughout the state of Mato Grosso, being: 1) Campus Barra do Garças; 2) Rondonópolis Campus; 3) Cuiabá Bela Vista Campus; 4) Cuiabá Octayde Campus; 5) Cáceres Campus; 6) Tangará da Serra Advanced Campus; 7) Campus Campo Novo do Parecis; 8) Juina Campus; and 9) Sorriso Campus.

Article 4 of the Internal Rules of the Active Business Incubator of IFMT brings as the incubator’s mission “to disseminate the entrepreneurial culture within the federal institute of Mato Grosso, fostering and supporting the generation of creative economy and solidarity economy enterprises, developing and offering competitive and differentiated products and services to the market.” (IFMT, 2017, p. 1).

2.4.1 OF THE STRUCTURE OF THE ATIVA INCUBADORA

In an analysis of the Internal Rules of the Active Business Incubator, table 2 is presented below with the hierarchical order of the structural:

Table 2 – Structural Hierarchy of the Ativa Incubadora Business of IFMT

| Name | Local | Composition | Definition |

| Deliberative Council | Management Office/Rectory | Rector (President), Pro-Rector of Extension, Pro-Rector of Research and Innovation, Pro-Rector of Administration, Director of Extension, Executive Management, Coordinator of the Center for Technological Innovation. | Maximum decision-making body within the Active Business Incubator, also constituting a space for study and preparation of knowledge aimed at the action of the institute with incubated enterprises and junior companies. |

| Executive Management | Management Office/Rectory | Server appointed by the rector of IFMT. | It enforces the decisions, guidelines and norms established by the Deliberative Council, so that its objectives are achieved. |

| Management Board | Local Incubator Core | General Director of the campus (President), Director/Extension Coordinator, Director/Coordinator of Research and Innovation, Director/Head of Administration and Planning Department, Local Management. | Maximum organ of the Active Incubator Center on the campus where it is located. It functions as an extension of executive management, to ensure compliance with established guidelines, policies, standards, rules and procedures. |

| Local Management | Local Incubator Core | A server appointed by the Campus Director General. | Body in charge of coordinating all actions in the Active Incubator Center of the campus and promoting the necessary conditions to achieve its purposes and objectives, negotiating with IFMT instances the demands and goals of the core and coordinating the progress of activities on campus. |

| Technical Committee | Local Incubator Core | Composed of specialists, consultants, researchers and people of notorious knowledge on the theme of the proposal presented, limited to a minimum of three members, indicated by the Local Management, and may be a server of IFMT, partner institutions and people in the community. | Commission responsible for assisting the Local Management, participating in the process of project elaboration of the enterprises, organizing and developing all activities related to the incubation process, also socializing the activities developed and promoting discussions and studies. |

Source: adapted from IFMT (2017), Internal Rules of The Ativa Incubadora Business .

Through Chart 2 we can perceive that although the deliberations are mostly the responsibility of higher bodies, the execution of the incubator activities is directly linked to the Executive Management, composed of the rectory server, and to the local managers of each of the centers arranged by the state campuses, who are in charge of ensuring the fulfillment of these activities on the campuses where they are crowded.

Thus, we can conclude that the structure of the Ativa Incubadora Business of IFMT ensures the execution of its activities in a functional way, through a composition that concentrates the main deliberations, but in order to ensure that each core can adapt the deliberations to the specific reality of its campus through a local management.

3. METHODOLOGY

This study aimed to measure perceptions about the Ativa Incubadora Business through the analysis of data from its Local Management and each of its nuclei during 2019, being, therefore, a collective case study, as stipulated by Gil (2002, p. 139):

A collective case study is one whose purpose is to study characteristics of a population. They are selected because it is believed that through them it becomes possible to improve knowledge about the universe to which they belong.

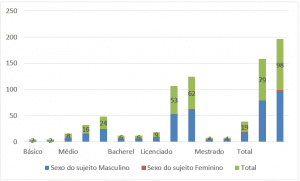

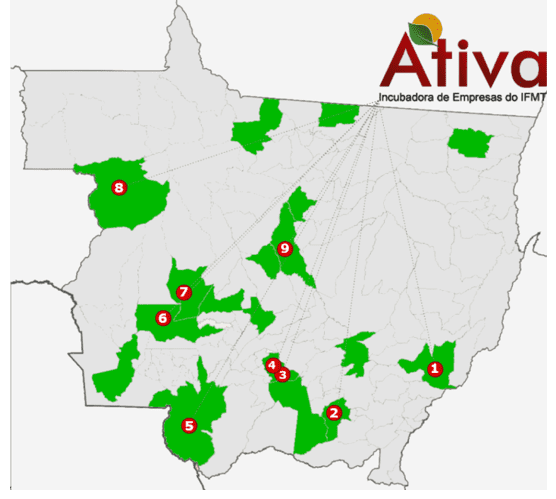

In order to collect the analyzed data, a questionnaire with a general aspect about GC for the Executive Management of Ativa Incubadora was used in the rectory and a questionnaire with specific aspects to the GC practices for each of the local managers of the 9 centers in the state of Mato Grosso. The questionnaire was sent to the local managers of the 9 nuclei active in 2019 and was answered by seven (Cuiabá, Bela Vista, Barra do Garças, Cáceres, Rondonópolis and Juína). The campuses’ nuclei that did not answer the questionnaire reported that although they were constituted, they had no opportunity to develop activities that year.

The questionnaire was applied in two ways, in a forum in May 2020 where the majority of managers were found and by e-mail for those who were not present. For the analysis of the general perception of GC in the Executive Management, a qualitative analysis was considered, whereas their understandings about this management model were collected, while for the analysis of the nuclei we opted for a quantitative approach, where they informed in which stage of implementation each of the 18 GC practices that were presented in the questionnaire were collected. For this study, the questionnaire was based on the instrument for measuring the publication “The challenge of Knowledge Management in the areas of administration and planning of federal institutions of higher education (IFES)” developed by Batista (2006) by Ipea.

The diagnosis of GC practices in relation to the nuclei took into account from those who did not have application plans for a given practice to those where the practice was already implemented and generating results, thus being possible to measure both which nuclei were more advanced in relation to the GC, and which practices were more effective today. For the intervention proposal, the literature was considered regarding the creation, transfer ence and management of knowledge according to the results obtained in the diagnosis.

4. DATA ANALYSIS

For the data analysis, the GC perspectives were divided primarily within the Executive Management of the Active Incubator in the rectory of the IFMT, and then considered an overview of the GC practices within each nucleus, where both the nuclei that least adhering to the practices were identified, and which practices have the most participation between them.

4.1 KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT IN THE EXECUTIVE MANAGEMENT OF THE ACTIVE INCUBATOR

Ativa’s Executive Management is occupied by a server who has been working in the planning/administration area for more than 5 years, being in charge of the incubator for a period between 2 and 3 years and who informs them of having basic knowledge about Knowledge Management.

In a broad respect, in relation to the applicability of GC in the Active Incubator states that although it is not one of the strategic priorities of the institution, there is a perception that it is necessary to have some way of managing knowledge.

This demonstrates a certain fragility in relation to the applicability of GC practices and the tangible return of results resulting from these practices, since, at the moment when the GC is not yet applied in a given organizational environment, its implementation depends on intensive actions, as it characterizes behavioral changes that will influence the flow of processes holistically, thus generating a cultural barrier as explained by Strauhs et. Al. (2012, p. 13) by defining this change as a challenge in “[…] consolidating an information culture so that all employees perceive and value the importance of sharing and using information to generate knowledge and consequently innovative products, services and processes.”

Similarly, the Executive Management declares that the perception of importance of the GC within its institution has not yet been reflected in the allocation of resources, be they human, financial or infrastructure, reflecting another fragility when it is an environment that, as it does not yet have any perspective of formalized implementation of GC , it is difficult to implement it without highlighting resources specifically for this purpose.

However, even if the GC itself is not formalized, it is emphasized that this is not an impediment for the practices related to them to be implemented, since the “Best Practices” reported that it is as in the implementation phase. When asked about work-flow systems and data warehouse and data mining tools to support GC, management reported that the current reality of the incubator does not apply.

4.2 DIAGNOSIS AND PROPOSALS FOR INTERVENTION OF KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT PRACTICES IN THE CENTERS OF ATIVA INCUBADORA

In order to preserve the identity of each campus, the samples were treated as “A” to “G”, as followed by seven responses to the questionnaires. Initially, the managers of the centers were asked how long they had been working in the Area of Management and Planning and how long they were as local managers of their centers, together with a question about what was their level of familiarity with the term “Knowledge Management”. This initial analysis is given in order to verify if GC practices suffer any influence according to management experience or their knowledge of the area in a general aspect.

For each GC practice of the questionnaire, they should opt for one of the five levels of stage of implementation of that action in its core, where according to the measuring instrument that supported this study, provided in the publication “The challenge of Knowledge Management in the areas of administration and planning of Federal Institutions of Higher Education (IFES)” which discloses results of studies directly or indirectly developed by Ipea , the internships referred to: (0) There are no deployment plans, (1) Planned for the future, (2) They are in the process of being implemented, (3) They are already implemented and (4) They are already implemented and presenting important and relevant results.

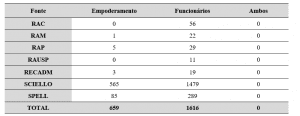

Thus, we considered the provision in Chart 3 below, where, evaluating 18 GC practices and the responses of their stages from (0) to (4), we made the sum and average of the 18 responses of each nucleus for the respective practices, first having those nuclei that were closer to the mean “4”, thus being the most advanced in the GC, for those with the lowest average.

Table 3 – Diagnosis of the centers of the Active Incubator according to the stage of implementation of Knowledge Management practices:

| Cores | The | B | C | D | And | F | G | Average of the stage of implantation of the evaluated GC practice, from the best to the least scored: |

| Working time in the area of Management and Planning: | 2 to 3 years | 4 to 5 years | More than 5 years | More than 5 years | More than 5 years | More than 5 years | More than 5 years | |

| Core Management Time: | 1 to 2 years | 1 to 2 years | More than 5 years | 2 to 3 years | 1 to 2 years | Less than 1 year | Less than 1 year | |

| Familiarity with the term “Knowledge Management”: | No | High | High | Basic | Basic | Low | Basic | |

| GC PRACTICE | DEPLOYMENT STAGE | |||||||

| Forums (face-to-face and virtual) /mailing lists | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3,000 |

| Communities of practice/knowledge communities | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1,857 |

| Mentoring | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1,857 |

| Coaching | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1,714 |

| Organizational memory/lessons learned/knowledge bank | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1,714 |

| Narratives | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1,714 |

| Corporate education | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1,571 |

| Collaboration tools such as portals, intranets, and extranets | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1,143 |

| Content management | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1,429 |

| Management of intellectual capital/management of intangible assets | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1,286 |

| Electronic Document Management (GED) | 4 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,286 |

| Internal and external benchmarking | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1,000 |

| Organizational/business intelligence/competitive intelligence systems | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,000 |

| Corporate University | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0,857 |

| Knowledge mapping or auditing | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0,714 |

| Individual skills bank/yellow pages talent bank | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0,571 |

| Organizational skills bank | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0,286 |

| Competence management system | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0,143 |

| Average of the evaluated nucleus, from best to least rated: | 2,611 | 2,389 | 1,500 | 1,000 | 0,667 | 0,500 | 0,333 | |

Source: prepared by the authors.

Analyzing the provisions of Chart 3, it is perceived that there is relevance between the level of knowledge of the term “Knowledge Management” and the application of practices by managers, since nuclei B and C, which responded with high familiarity with the term, are better averages than most, however, not being a rule, since nucleus A , being the only one to answer that he had no familiarity, he still achieved the best average in relation to the implementation of the practices. Another pattern to be observed is that those centers where their local managers had been responsible for less than 1 year as responsible for management were the ones with the lowest averages in the implementation of GC practices.

In a general aspect analysis, we can see that although most nuclei have an average below 2,000 indicating a low support of GC practices, the panorama of the practices themselves and the perception of their importance is not unfavorable, whereas of the 126 stages reported (considering the stage of each of the 18 practices for each of the seven nuclei) , only 48 were indicated as the stage “(0) There are no implementation plans”, which confirms the provisions in the literature that innovation environments in general are intrinsically linked to the generation and flow of knowledge, and, therefore, end up developing perceptions of how to manage this knowledge to ensure that innovation also occurs.

However, this does not cancel out the result that most GC practices are not yet effectively applied to the context of the nuclei, since 50 of the internships are between “(1) Planned for the future” and “(2) They are in the process of implementation”, against 16 stages that are at the level “(3) Are already implanted” and only 12 that are at the level “(4) are already implanted and presenting important and important results”.

For a more accurate diagnosis, the data were also arranged evaluating the means of each of the 18 GC practices performing the sum and the average of the seven responses for each practice, first having those that were closer to the mean “4”, thus being the most advanced in stages of implantation in the nuclei.

Thus, to analyze the character of these practices, the provisions of Batista (2006) are emphasized when he states that knowledge management begins with the process of knowledge creation, that is, before the execution of the process, when people, with the objective of learning before performing any action seek information and knowledge according to best practices, with organizational memory , or in the lessons learned and in the knowledge bank, through portals and intranets and also through the practice of benchmarking, observing that this type of access only occurs when they can effectively achieve the registration of that knowledge, which is the transformation of tacit knowledge into explicit. At this moment it is also possible to access the organizational skills bank and the individual skills bank/talent bank/yellow pages to identify specialists who may contribute the knowledge required for the process that is sought to measure. The author further states that it is after the application of the knowledge obtained that strategic information and knowledge about organizational processes can be transferred and shared through forums / mailing lists, virtual practice communities; corporate education; narratives; mentoring and coaching.

Thus, it is perceived that the centers of the Active Incubator have good practices with regard to knowledge transfer, with great results in relation to forums (face-to-face and virtual) / discussion lists and also a good dissemination of the practice spractices of practice communities /communities of knowledge, mentoring, coaching, narratives and corporate education.

This is an extremely relevant diagnosis whereas, although there is a gap between some nuclei in relation to other practices, when there is familiarity with the transfer of knowledge and its continuous processes in order to generate an effective socialization, it is possible to seek a balance in the leveling in relation to what needs to be improved through greater stimulation and intensification of knowledge transfer among those who already develop certain actions capable of positively impacting within the scope of what is aims to improve.

This, however, may have a not-so-effective optimization as long as there is no clarity as to who are those individuals who can, in fact, transfer the knowledge that is effective at the lanot point. This clarity would be possible if there were among the centers the practices of individual skills banking/yellow pages talent bank, organizational skills bank and a fluid skills management system, which are the practices that meet the lowest averages.

Thus, although for the transfer of knowledge the nuclei have practices that can be used in their favor, at this moment, when a specific individual is needed for a transfer practice, such as mentoring or coaching, for example, there will still be noises and slowness in the search for who would be the most qualified professional within the type of knowledge that one aims to socialize, which could easily be resolved with the implementation of an individual skills bank/talent bank/yellow pages, for example. Regarding the applicability of this practice as a catalogue of experts, Almeida et. al. (2016, p. 123) point out that:

This practice, although simple, is one of the most useful and necessary to be implemented, simply by identifying who knows what within the organization. In the vast majority of organizations, people hold information of who knows what from their personal network, which is quite limited. When the catalog of specialists is implemented, the possibilities multiply, since we can identify competencies in people that we would never identify if only the individual personal network of each one was used.

A proposal to enable the implementation of these records of competencies of individuals in order to formalize the registration of their knowledge is to use the moments and practices of knowledge transfer that are already properly stabilized in the nucleus and that occur more widely, that is, to collectively embrace the individuals involved, such as forums (face-to-face and virtual)/mailing lists, practice communities/knowledge communities and also the practice of corporate education, which is a regular average. At the time of knowledge transfer, by collecting which are the specific areas of knowledge shared and their authors, the feasibility of building a record on who are the most apt professionals within each specificity begins.

It is worth mentioning that it is not only the area of training and performance of professionals that must be collected in case of implementing a bank of individual competencies, because knowledge, being something very intimate and personal, especially with regard to tacit knowledge, all its totality generated by the professional’s particular experience should be considered. Almeida et. al. (2016, p. 69) brings the importance of these competencies being mapped while it is the combination of them that is responsible for the processes of an organization in general:

It is essential to understand that organizations are the result of a set of competencies that, combined and working together, will promote desired results. We can divide these competencies into institutional and individual. […] Individual individuals, related to employees, mean knowing how to act by mobilizing, integrating, transferring knowledge, resources and skills that add economic value to the organization and social value to the individual.

Thus, it is necessary to think about strategies for the feasibility and applicability of a mapping of these competencies within the nuclei of the Ativa Incubadora, which, even being a systemic incubator where the nuclei integrate with each other, can have great benefit by ensuring that the nuclei know what are the competencies of professionals who work in incubator activities even in nuclei geographically distant from theirown and who have not yet had the opportunity to have contact.

Regarding practices that enable knowledge management such as records of information that can be accessed within the nuclei, such as organizational memory/lessons learned/knowledge bank, collaboration tools such as portals, intranets and extranets, content management and management of intellectual capital/management of intangible assets; it is balanced in its classifications, because although they present regular averages, they are perpetuated as practices already implemented or with implantation plan in most nuclei. This is important, because, at the moment when there is a gap in the scope of the search for which professionals are more trained in certain types of knowledge and, therefore, could be sources of their transference, the records partially supply this need for those who are in this character of need.

Nevertheless, this demonstrates the potential of nuclei to establish knowledge recording practices that, in this way, could be better used also to optimize the records regarding professionals who have this knowledge, providing a better performance in the practices associated with these determinations that are severely out of date.

Finally, it is necessary to observe the practice of electronic document management (GED), which is also important for the registration and flow of knowledge, is with a regular average of 1.286, however, only because in samples A and B its internship was classified with the best placement, being “(4) Already implanted and presenting important and relevant results.”, but obtained classification (1) in another nucleus and (0) in all four others. Thus, a palpable imbalance between the nuclei is noticeable, which can be supplied through the sharing of nuclei A and B with the rest through practices such as the socialization of best practices and narratives.

5. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Responding to what led this study, it is possible to perceive that the Active Business Incubator of IFMT, through its nuclei, has GC practices in its daily routine in a comprehensive way, while most have perceptions of implementation or implemented, however, it is emphasized that even with these perceptions, most of the practices do not occur, still, in an intensified way and generate results.

However, the existence of this perception of practices between nuclei corroborates the link between GC and innovation, because, since the incubator is a habitat for innovation while dealing with innovative entrepreneurship, even the Executive Management does not have the applicability of the GC as a priority and most of the nuclei are not familiar with the term, the practices are perpetuated as current or future strategies in most of them.

However, the imbalance between the nuclei is clear while the averages vary between “2.611”, “2.389”, “1,500”, “1,000”, “0.667”, “0.500” and “0.333”, showing that although there are those where the practices already present relevant results, there are still most nuclei where the practices are not so strongly structured. However, there are strengths in a general aspect of knowledge transfer practices, which can be used as an institutional strategy through collective actions between the nuclei so that successful practices can be socialized and embraced also by lain nuclei.

As a suggestion for a future study, it is suggested the structuring of a process mapping that is able to accurately indicate how GC practices that are currently employed satisfactorily can be used to optimize the processes involved in those that are out of time, thus leveling the GC cycle within these institutions through the use of practices they already have.

REFERENCES

ALVARENGA NETO, R. Gestão Do Conhecimento Em Organizações: Proposta De Mapeamento Conceitual Integrativo. Orientador: Ricardo Rodrigues Barbosa. 2005. 400 p. Tese (Doutorado em Ciência da Informação) – Programa de Pós Graduação em Ciência da Informação da UFMG, Belo Horizonte, 2005. Disponível em: <http://hdl.handle.net/1843/EARM-6ZGNE6> Acesso em: 23/08/2020.

ALMEIDA, A; BASGAL, D. M; RODRIGUEZ, M. Y; FILHO, W. Inovação e Gestão do Conhecimento. Rio de Janeiro: FGC Editora, 2016.

ANPROTEC. Mecanismo de geração de empreendimentos e ecossistemas de inovação. 2019. Disponível em: <http://anprotec.org.br/site/sobre/incubadoras-e-parques/> Acesso em 23/08/2020.

ATIVA. Onde estamos. 2019. Disponível em <https://ativa.ifmt.edu.br/?page_id=433> Acesso em 23/12/2019.

BATISTA, F. O Desafio da Gestão do Conhecimento nas áreas de Administração e Planejamento das Instituições Federais de Ensino Superior (IFES). Brasília: Ipea, 2006. Disponível em: <https://www.ipea.gov.br/portal/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=4779> Acesso em 23/08/2020.

BATISTA, F. Modelo de Gestão do Conhecimento para a Administração Pública Brasileira: Como implementar a Gestão do Conhecimento para produzir resultados em benefício do cidadão. Brasília: Ipea, 2012. Disponível em: <http://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/handle/11058/754> Acesso em: 23/08/2020.

BUREN, I. M; RAUPP, F. Compartilhamento do Conhecimento em Incubadoras de Empresas: um Estudo Multicasos das Incubadoras de Santa Catarina Associadas à Anprotec. 2003. Anais do Enanpad. Disponível em <http://www.anpad.org.br/admin/pdf/enanpad2003-act-0915.pdf> Acesso em 23/08/2020

CONG, X; PANDYA, K. V. Issues of Knowledge Management in the Public Sector. The Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management, 1, pp. 25-33. [online] Disponível em: < http://www.ejkm.com/issue/download.html?idArticle=17> Acesso em 23/08/2020

DEPINÉ, A; TEIXEIRA, C. S. Habitats de inovação: conceito e prática – São Paulo: Perse. 294p. v.1: 2018. Disponível em: < http://via.ufsc.br/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/HABITATS-DE-INOVACAO-conceito-e-pratica.pdf> Acesso em 23/08/2020.

FIALA, N; ANDREASSI, T. As incubadoras como ambientes de aprendizagem do empreendedorismo. Administração: Ensino e Pesquisa. Rio de Janeiro, V. 14, Nº 4, p. 759–783, Out Nov Dez, 2013. Disponível em: <https://raep.emnuvens.com.br/raep/article/view/51/164> Acesso em 23/08/2020.

FURLANI, T. Engajamento De Corporações Com Startups Na Quarta Era Da Inovação: Recomendações E Sugestões. Dissertação (mestrado) – Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Centro Tecnológico, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Engenharia e Gestão do Conhecimento, Florianópolis, 2018. Disponível em: <https://repositorio.ufsc.br/handle/123456789/194468> Acesso em: 23/08/2020.

GIL, A. C. Como elaborar projetos de pesquisa. São Paulo: Editora Atlas S.A. – 4ª Edição, 2002.

IFMT. O que é Incubadora de Empresas? 2019. Disponível em < http://proex.ifmt.edu.br/conteudo/pagina/o-que-e-incubadora-de-empresas/> Acesso em: 23/08/2020.

IFMT. Regimento Interno da Ativa Incubadora de Empresas, 2017. Disponível em: <http://proex.ifmt.edu.br/media/filer_public/8d/77/8d776283-0e4a-4c2c-85cd-293ee6d57322/resolucao_0842017.pdf> Acesso em: 23/08/2020.

LIMA, N; ZIVIANI, F; REIS, R. V. Estudo das práticas de gestão do conhecimento no Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Maranhão. Encontros Bibli: revista eletrônica de biblioteconomia e ciência da informação, Florianópolis, v. 19, n. 41, p. 105-126, Dez. 2014. ISSN 1518-2924. Disponível em: <https://periodicos.ufsc.br/index.php/eb/article/view/1518-2924.2014v19n41p105>. Acesso em: 23 ago. 2020. doi:https://doi.org/10.5007/1518-2924.2014v19n41p105.

MAGNANI, M; HEBERLÊ, A. Introdução a Gestão do Conhecimento: Organizações como sistemas sociais complexos. – Pelotas: Embrapa Clima Temperado, 2010. Disponível em: < http://www.infoteca.cnptia.embrapa.br/infoteca/handle/doc/867731> Acesso em: 22/08/2020.

MARTINS, G; et. al. A interação universidade/empresa nas Incubadoras de Empresas de Base Tecnológica de Minas Gerais. Anais do XXIV Simpósio de Gestão de Inovação Tecnonlógica. Gramado, Out. 2006. Disponível em: <http://www.anpad.org.br/admin/pdf/RED801.pdf> Acesso em 23/08/2020.

MÜLLER, R; et. al. Contribuições da Gestão do Conhecimento para as Incubadoras de Empresas: uma investigação nas incubadoras tecnológicas da cidade Curitiba, PR. Anais do XVI Congresso Latino-iberoamericado de Gestão de Tecnologia, Out. 2015. Disponível em: < http://altec2015.nitec.co/altec/papers/295.pdf> Acesso em: 23/08/2020.

PIMENTA, R. C. Q.; NETO, M. Gestão da Informação: um estudo de caso em um instituto de pesquisa tecnológica. Prisma.com, revista de Ciências e Tecnologias de Informação e Comunicação. Nº 9, p. 128-157, 2009. Disponível em <http://ojs.letras.up.pt/index.php/prismacom/article/view/2055/3100> Acesso em: 23/08/2020.

PROBST, G; RAUB, S; ROMHARDT, K. Gestão do conhecimento: os elementos construtivos do sucesso. Porto Alegre: Bookman, 2002.

RAUPP, F; BEUREN, I. M. Gestão Do Conhecimento Em Incubadoras Brasileiras. Future Studies Research Journal: Trends and Strategies [FSRJ], [S.l.], Vol. 2, Nº. 2, p. 186-210, Dez. 2010. ISSN 2175-5825. Disponível em: <https://www.revistafuture.org/FSRJ/article/view/61/99>. Acesso em: 23/08/2020.

SETZER, V. W. Dado, Informação, Conhecimento e Competência, 2014. Disponível em: < https://www.ime.usp.br/~vwsetzer/dado-info.html> Acesso em: 23/08/2020.

SILVA, S. A relevância das incubadoras de empresas no mundo contemporâneo. Ponto-e-Vírgula : Revista de Ciências Sociais, [S.l.], n. 6, mar. 2013. ISSN 1982-4807. Disponível em: <https://revistas.pucsp.br/pontoevirgula/article/view/14049/10351> Acesso em: 23/08/2020.

STRAUHS, F; et. al. Gestão do Conhecimento nas Organizações – Curitiba: Aymará Educação, 2012. – (Série UTFinova). ISBN 978-85-7841-783-3 (material impresso) ISBN 978-85-7841-784-0 (material virtual). Disponível em: < http://repositorio.utfpr.edu.br/jspui/bitstream/1/2064/1/gestaoconhecimentoorganizacoes.pdf> Acesso em: 22/08/2020.

WIIG, K., M. Application of Knowledge Management in Public Administration. Paper Prepared For Public Administrators of the City of Taipei, Taiwan, ROC, 2000. Later published as Wiig, K.M. (2002) ‘Knowledge management in public administration’, Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 224-239.

WIIG, K., M. The Importance of Personal Knowledge Management in the Knowledge Society. 2011 for “Personal Knowledge Management: Individual, Organisational and Social Perspectives” A book edited by Dr David J Pauleen and Professor G E Gorman. Disponível em: < https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271509540_The_Importance_of_Personal_Knowledge_Management_in_the_Knowledge_Society> Acesso em: 23/08/2020.

[1] Graduated in Accounting From the Federal University of Mato Grosso Rondonópolis campus, (2017).

[2] Graduated in Agronomy from the Federal University of Mato Grosso (2011) Master’s degree in Tropical Agriculture from the Federal University of Mato Grosso (2015).

Submitted: September, 2020.

Approved: October, 2020.