REVIEW ARTICLE

SBRUZZI, Felipe Augusto [1], SILVA, Kelly Cristina da [2], TELLES, Sérgio Mazero [3], LIMA, Sirlene de Sousa [4], SANTANA, Claudinei Alves [5]

SBRUZZI, Felipe Augusto. Et al. Follow-up form for adult patients with leukemia using Imatinib. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 05, Ed. 10, Vol. 02, pp. 92-112. October 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access Link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/health/using-imatinib, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/health/using-imatinib

SUMMARY

Introduction: Chronic Myeloid Leukemia is a type of malignant blood neoplasia that is mainly characterized by the presence of the Philadelphia chromosome that originates the oncoprotein BCR-ABL. It has increased tyrosine kinase activity, thus causing changes in intracellular signaling pathways and promoting uncontrolled proliferation, cellular dysfunction and absence of apoptosis. Despite the low incidence of the disease, 1.5 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, therapy with Imatinib, a potent inhibitor of BCR-ABL, changed the prognosis of the disease and extended the life expectancy of patients, transforming a fatal disease into a chronic condition. Objective: To develop a form for regular monitoring of these patients by the clinical pharmacist to ensure safe and effective pharmacotherapy. Methodology: Narrative-type literature review was initiated from the problem question: ‘“What data should be collected by the Clinical Pharmacist during pharmaceutical assistance to assess and improve adherence in adult patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia using Imatinib?” , followed by search for articles in PubMed databases and government websites. Subsequently, work selection and critical analysis were carried out to build a model form to be applied in the act of dispensing. Result and Discussion. Eleven articles were selected. The patient’s low adherence to the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia can result in potentially life-threatening. Therefore, the follow-up form to be applied by the clinical pharmacist when dispensing imatinib mesylate is a viable and low-cost strategy to improve adherence to pharmacotherapy and promote a better response to treatment. Conclusion: The systematic and standardized documentation of adherence and adverse effects by the Clinical pharmacist allows the implementation of actions by the multidisciplinary team of continuous improvements in order to maximize the quality of care provided to patients as well as the quality of life.

Key Words: Leukemia, pharmacotherapeutic follow-up, Imatinib.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer is the name given to a set of more than one hundred pathologies, which has as common characteristics the initiation by damage in specific DNA genes and the autonomous and disordered growth of cells that acquire the ability to invade adjacent organs and tissues resulting in functional disorders (THAVAMANI et al., 2014).

This abnormal cell proliferation is known as neoplasia and in practice it is called tumor, and can be classified as malignant or benign (INSTITUTO NACIONAL DO CÂNCER, 2019).

A special group of malignant neoplasms are leukemias, which are characterized by abnormal proliferation of bone marrow cells precursors of the white lineage (JULIUSSON And HOUGH, 2016; LIU et al., 2019). Leukemias can be classified according to the type of affected cell, lymphocytic or myeloid, and as to the characteristic, acute or chronic (SACHDEVA et al., 2019).

Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) is a type of blood disorder characterized by an increase in the number of leukocytes with left deviation, splenomegaly and the presence of the Philadelphia chromosome (Ph), which results from reciprocal translocation between chromosomes (9;22) (q34;q11), giving rise to bcr-abl protein, with increased tyrosine kinase activity (FLIS And CHOJNACKI, 2019).

The BCR-ABL protein is present in more than 90% of patients with CML, and its hyperactivity stimulates the release of cell proliferation effectors and apoptosis inhibitors, and its activity is responsible for the process of cancer formation in CML (DI FELICE et al., 2018).

The discovery of this molecular alteration in addition to optimizing the diagnosis of CML also provided the development of therapies aimed at this molecular alteration, and methods of monitoring minimal residual disease, providing an improvement in treatment (BORTOLHEIRO AND CHIATTONE, 2008).

CML presents 3 distinct clinical phases that arise throughout the course of the disease, being classified as chronic phase, transformation phase and final or blast phase (HEFNER et al., 2016).

Traditionally, cancer treatment can be performed through surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy modalities, and the combination is common to obtain a better clinical outcome (NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUO, 2019).

Classical chemotherapy aims at the destruction of cells in rapid replication that suggest from mutations and/or important changes in DNA, however, normal tissue cells that also have rapid replication are destroyed thus providing numerous adverse effects to patients (BAGNYKOVA et al., 2010).

In cancer cells, such as CML, intracellular signaling pathways are altered, promoting uncontrolled proliferation, cellular dysfunction and absence of apoptosis (ANDERSON et al., 2015). Based on a better understanding of these processes, initiated in the 1980s, drugs called tyrosine kinase inhibitors (ITQ) began to be studied (CHABNER And ROBERTS, 2005).

In CML due to its pathognomonica characteristic, the BCR-ABL oncogene, has become the ideal candidate for the “magic bullet” conceived by Paul Ehrlich (Chabner and Roberts, 2005). Thus, the “Target Therapy” with ITQ seeks to selectively inhibit the deregulated signaling pathways of neoplastic cells of patients with CML, having as the first drug used imatinib mesyate, a potent INHIBITOR of BCR-ABL (DREWS, 2006; MOULIN et al., 2017).

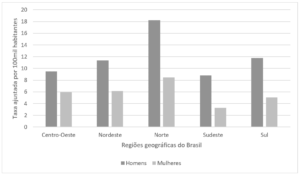

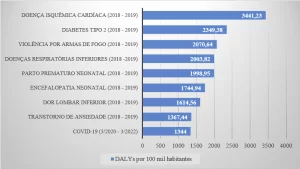

Due to the aging and population growth, cancer incidence and mortality has been growing around the world (BRAY et al., 2018). In Brazil, the National Cancer Institute (INCA) estimates that for each year of the 2018/2019 biennium 600,000 new cases of cancer are diagnosed, among these leukemias appear in 9th place among men with 5,940 new cases and 10th in women with 4,860 new cases (INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE CÂNCER, 2017).

CML accounts for approximately 15% of new cases of leukemia, with an estimated risk of 1.5 cases per 100,000 people (RYCHTER et al., 2017). Despite the low incidence compared to other types of cancer (lung, prostate, breast), due to imatinib mesilate therapy, patients with CML showed a considerable improvement in the five-year survival rate and modified the prognosis of the disease (TRIVEDI et al., 2014; SAUSSELE et al., 2018; TAN et al., 2019; LATREMOUILLE-VIAU et al., 2017).

For patients diagnosed in the mid-1970s, the five-year survival rate was 22%, from 2008 to 2014, 69%, and currently most patients receiving TQI have life expectancy compatible with normal people, making CML currently considered as a chronic condition that requires regular follow-up by the health team (SIEGEL et al. , 2019).

The treatment of CML requires the integrated action of the multidisciplinary team, and the pharmaceutical professional is indispensable in the pharmacotherapeutic follow-up (PA) of cancer treatment to ensure a safe and effective pharmacotherapy (SOUZA et al., 2018).

PA is a personalized practice in which the clinical pharmacist has the responsibility for guidance, detection, prevention and resolution of drug-related problems, covering the adverse effects of chemotherapy and the therapy used, as well as the techniques of administration, adherence to treatment and drug interactions (CALADO et al., 2019).

Given the complexity of CML, the follow-up performed by the clinical pharmaceutical professional is essential for the efficacy of treatment.

OBJECTIVE

Build a pharmacotherapeutic follow-up form model for adult patients with positive BCL-ABR Chronic Myeloid Leukemia using Imatinib Mesiduct.

METHODOLOGY

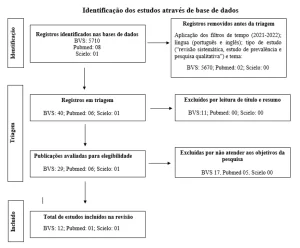

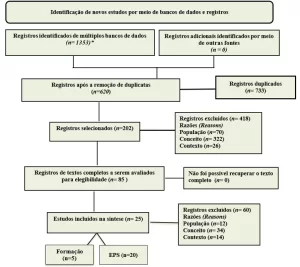

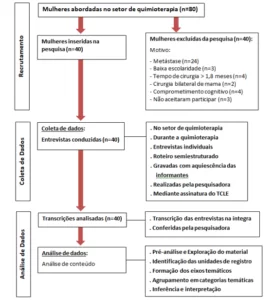

The work is a literature review of the narrative type. Thus, from the problem question: “What data should be collected by the Clinical Pharmacist during pharmaceutical assistance to evaluate and improve the adherence of adult patients with Chronic Myeloid Leukemia using Imatinib?” a search was carried out on the PubMed platform based on the PICO strategy and the descriptors were used: “leukemia, myelogenous, chronic, bcr-abl positive” AND “adherence medication”. The articles of the last 5 years were considered and the search was carried out in the database from June to December 2019.

The inclusion criteria were: articles available in full online, in English, which had as population adult patients, and with the theme of evaluation of drug adherence in CML. As exclusion criteria were: articles that evaluated exclusively another drug other than imatinib mesysirate, which did not use a form.

Also, to make up the form were consulted government sites.

RESULT AND DISCUSSION

The search on the Pubmed website with the descriptors resulted in 52 articles and of these, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 11 were selected to make up the literature review in the preparation of the form.

These articles are presented in Table 1 in order of descending date of publication.

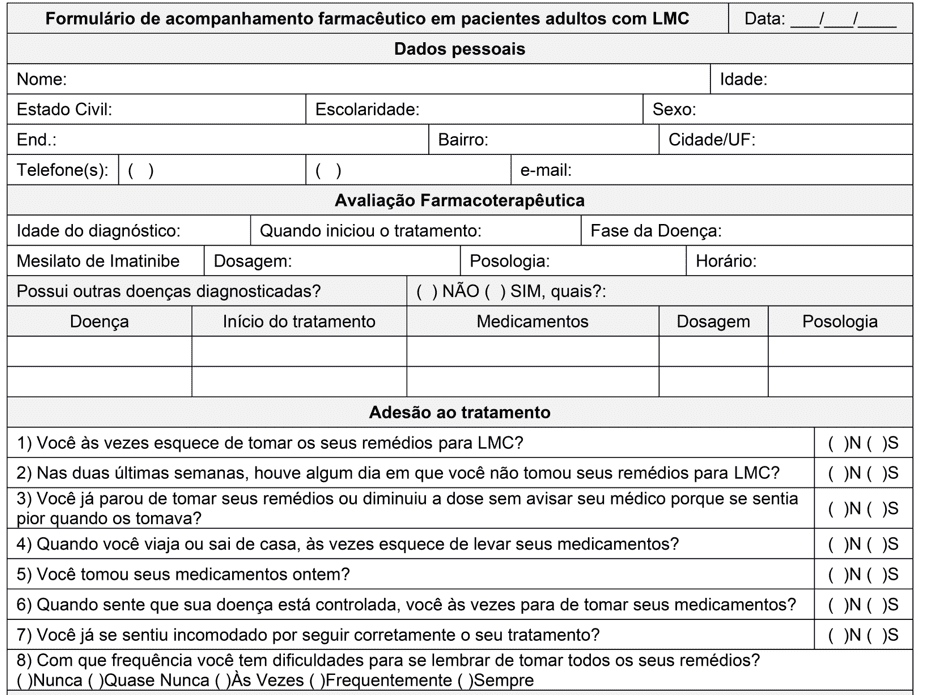

According to what was observed by Moulin et al., the inclusion of the Clinical Pharmacist during the treatment of patients with CML not only improved adherence to treatment and decreased the adverse drug reactions (ADR) reported by the patients, but also improved cytogenetic parameters (MOULIN et al., 2017). In this study, after 4 months of follow-up, the authors found a lower expression of the Philadelphia chromosome in the monitored group in relation to the unmonitored control. In the monitored group, the complete cytogenetic response observed increased from 87.0% to 95.6% of patients while in the unmonitored group it remained in 61.5%. Thus, the application of a form at the time of dispensation is an effective strategy to accompany the patient and improve adherence to treatment. To achieve this goal, a pharmaceutical follow-up form was elaborated in adult patients with CML (Annex I).

The first part of the form is intended to collect patients’ personal data to identify and facilitate contact with the patient. This is because some of the selected studies show that in some populations the ades can be favored by some socioeconomic characteristics, but the studies differ as to which are more present in the population. Tsai et al (2018) found in the study population that older patients and married patients have better adherence. According to Rychter et al (2017) the presence of at least 1 comorbidity and age over 65 years are favorable characteristics for adering. In contrast, Unnikrishnan et al (2016) and Hefner et al (2016) found no correlation between the socioeconomic characteristics of the studied population and treatment adhering. Thus, it is observed that the correlation between socioeconomic data and adherence varies according to the population studied, not being a predictive parameter for patient adherence or non-adherence.

Table 1.A – Articles selected based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, descending order of year of publication.

| Author/Year | Title | Goals | Form Of Adecin | N(1) | Country | Medicines |

| MULU FENTIE et al., 2019 | Prevalence and determinants of non-adherence to Imatinib in the first 3-months treatment among newly diagnosed Ethiopian’s with chronic myeloid leukemia. | To evaluate the prevalence and reasons for non-adhering to Imatinib in patients with CML(2) who were recently diagnosed in the first 3 months of treatment. | MMAS-8(3) | 147 | Ethiopia | Imatinib |

| TSAI et al., 2018 | Side effects and medication adherence of tyrosine kinase inhibitors for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in Taiwan. | Clarify the influence of adverse effects on adherence in Taiwanese patients with CML(2). | MMAS-8(3) | 58 | Taiwan | Imatinibe

Dasatinibe Nilotinibe |

| HEFNER et al., 2017 | Adherence and Coping Strategies in Outpatients With Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Receiving Oral Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. | To evaluate adherence and coping strategies in patients outside the hospital environment with CML(2). | BAASIS(4) | 35 | Germany | Tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

(1) N = Number of participants; (2) CML = Chronic myeloid leukemia; (3) MMAS-8 = 8-item Morisky Therapeutic Adherence Scale; (4)BAASIS = Basel Scale for Immunosuppressive Drug Adherence Assessment; (5) MMAS-4 = 4-item Morisky Therapeutic Adherence Scale.

Table 1.B – Articles selected based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, descending order of year of publication.

| Author/Year | Title | Goals | Form Of Adecin | N(1) | Country | Medicines |

| RYCHTER et al., 2017 | Treatment adherence in chronic myeloid leukaemia patients receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitors. | Evaluate treatment adhering to adult Polish patients with CML(2) | Form developed for the study. | 140 | Poland | Imatinib

Dasatinib Nilotinib |

| GEISSLEr et al., 2017 | Factors influencing adherence in CML and ways to improvement: Results of a patient-driven survey of 2546 patients in 63 countries. | To evaluate the extent of sub-optimal adherence and investigate the reasons and patterns of adherence behavior of patients with CML(2) around the world. | MMAS-8(3) | 2546 | 63 countries | Imatinib

Dasatinib Nilotinib Other treatment |

| MULUNEH et al., 2016 | Patient perspectives on the barriers associated with medication adherence to oral chemotherapy. | Analyze through a questionnaire the use of oral chemotherapy and identify opportunities for improvement in the following. | Questionnaire adapted with 30 questions | 93 | United States | Oral chemotherapy |

(1) N = Number of participants; (2) CML = Chronic myeloid leukemia; (3) MMAS-8 = 8-item Morisky Therapeutic Adherence Scale;(4) BAASIS = Basel Scale for Immunosuppressive Drug Adherence Assessment; (5) MMAS-4 = 4-item Morisky Therapeutic Adherence Scale

Table 1.C – Articles selected based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, descending order of year of publication.

| Author/Year | Title | Goals | Form Of Adecin | N(1) | Country | Medicines |

| MOULIN et al.

Nov/201614 |

The role of clinical pharmacists in treatment adherence: fast impact in suppression of chronic myeloid leukemia development and symptoms | To evaluate the role of the clinical pharmacist in the treatment of patients with CML(2), as well as the participation of the clinical pharmacist. | MMAS-4(5) | 23 | Brazil | Tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

| KEKÄLE et al., 2016 | Impact of tailored patient education on adherence of patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia to tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a randomized multicentre intervention study. | To evaluate the influence of personalized education to the patient on adherence to ITQ in patients with CML(2). | MMAS-8(3) | 86 | Finland | Tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

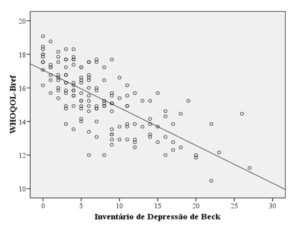

| UNNIKRISHNAN et al., 2016 | Comprehensive Evaluation of Adherence to Therapy, Its Associations, and Its Implications in Patients With Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Receiving Imatinib. | Evaluate adforebation and quality of life in patients with CML(2) receiving Imatinib for a long period of time. | MMAS-8(3) | 221 | India | Imatinib |

(1) N = Number of participants; (2) CML = Chronic myeloid leukemia; (3) MMAS-8 = 8-item Morisky Therapeutic Adherence Scale;(4) BAASIS = Basel Scale for Immunosuppressive Drug Adherence Assessment; (5) MMAS-4 = 4-item Morisky Therapeutic Adherence Scale

Table 1.D – Articles selected based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, descending order of year of publication.

| Author/Year | Title | Goals | Form Of Adecin | N(1) | Country | Medicines |

| HOSOYA et al., 2015 | Failure mode and effects analysis of medication adherence in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia | Identify how low adherence occurs in patients with CML(2) using Failure Mode and Effect Analysis. | Form developed for the study | 54 | Japan | Imatinibe

Dasatinibe Nilotinibe |

| BRECCIA et al., 2015 | Adherence and future discontinuation of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia. A patient-based survey on 1133 patients. | Investigate adherence and potential benefit in quality of life, satisfaction with treatment and social life in patients with CML(2) | Form developed for the study. | 1133 | Italy | Tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

(1) N = Number of participants; (2) CML = Chronic myeloid leukemia; (3) MMAS-8 = 8-item Morisky Therapeutic Adherence Scale;(4) BAASIS = Basel Scale for Immunosuppressive Drug Adherence Assessment; (5) MMAS-4 = 4-item Morisky Therapeutic Adherence Scale

One of the attributions of the clinical pharmacist is the evaluation of pharmacotherapy, so that the patient can safely use the medications he needs, at the appropriate doses, frequency and schedules, thus achieving the therapeutic objectives. In order to this, specific fields were reserved to collect the age of diagnosis, initiation of treatment, disease phase and parameters related to imatinib pharmacotherapy.

In Brazil, Ordinance No. 1,219 of November 4, 2013 establishes the clinical protocol and therapeutic guidelines for CML in adults and is a reference for the pharmacotherapeutic evaluation of these patients. In this, it is recommended to use Imatinib as a first-line treatment and what pharmacotherapy is for the chronic (PC) and transformation or accelerated (TA) phases (BRASIL, 2013).

In PC it is recommended a single dose 400 mg/day a day orally after the largest meal of the day, and may escalate in two doses of 300 mg, one in the morning and the other in the evening, if after three months an inadequate response, loss of previous response or progression of the disease. In relation to TA, the recommended dose is 600mg/day and may be elevated up to 800 mg/day in blast crises (BRASIL, 2013).

In addition to having a fundamental role in patient treatment adhering, the clinical pharmacist should also identify, evaluate and intervene in drug interactions. To evaluate possible drug interactions during the use of imatinib, the presence of other diseases and pharmacotherapies of these diseases is evaluated in the form. In the case of drug interactions, the pharmacist should be aware of drugs that have hepatic metabolization, because imatinib is metabolized in this route by the enzyme CYP3A4 (GLIVEC, 2020). The maintenance of a blood concentration greater than 300mg is extremely important for the success of the molecular/cytogenetic response and increased survival without disease progression (BRASIL, 2013). Therefore, inducers of this enzyme such as dtethasone and Hypericum perforatum, which may reduce the plasma concentration of Imatinib, should be avoided. As well as inhibitors like ketoconazole, clarithromycin that could decrease metabolism and increase concentrations of imatinib leading there is an increase in ADR (GLIVEC, 2020).

The second part of the article aims to evaluate the patient’s treatment. According to the definition of the World Health Organization (WHO), adherence in chronic diseases is the degree to which a person’s behavior agrees with the recommendations of a health professional, and behavior can be represented by medication intake, diet follow-up or lifestyle changes (WHO, 2003)

In the selected articles, the following were measured through questionnaires that evaluate this behavior through actions relevant to the treatment of CML, such as: forgetting one or more doses, dose change without notifying the prescriber, not taking medication because he feels good or because he has an adverse reaction. The most used questionnaire model in the articles (six out of eleven selected) to assess adherence was the Morisky Therapeutic Adherence Scale, with 8 items (MMAS-8) being the most frequent. In front of this, the MMAS-8 was chosen for the composition of the accompanying form.

Another important factor for the choice was the time required for application and the ease to classify the patient. The MMAS-8 consists of seven questions with “yes” or “no” alternatives, and one item (the last) that features a likert scale of 5 points (ranging from 0 points to “always” to 1 point to “never”). Each item assing a specific behavior of medication use and is not a determinant of the behavior of medications. MMAS scores can range from 0 to 8 and patients are classified into three levels of support: high strength (score 8); mean adeposition (score 6 to 7.75); and low adtake (<6).

A modified questionnaire of the Basel Scale for Immunosuppressive Drug Adepitus Assessment (BAASIS) was used by Hefner et al (2016). This has four “yes” or “no” questions and only one affirmative answer is needed to consider the patient as “non-adherent”, which can provoke a negative answer in the patient compared to the Classification of MMAS-8 (high, medium and low support). Another factor considered for choice was the absence in BAASIS of issues related to behavior “to stop taking medication when you feel that the disease is controlled”. This is because in some studies, it has been detected that patients tend to be more adherent in the first and second year after diagnosis, probably due to decreased symptoms and ADR become more evident than the disease itself (GEISSLER et al, 2017).

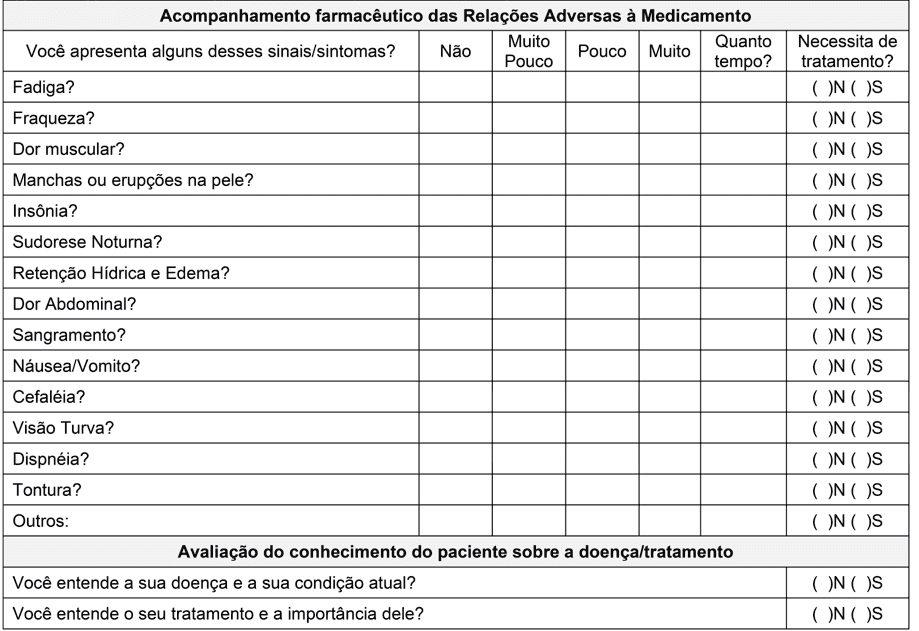

To assess ADR and its consequences on the ad, a third part was included in the form with questions about the most common reactions.

According to a cohort study conducted in Ethiopia by Mulu Fentie et al (2019), it was identified that the main reason for non-treatment support were adverse events related to Imatinib, to drugs that were 68.8%. And the main complaint about 68% were related to gastrointestinal effects. The study also shows that patients who did not experience any ADR were six times more likely to adhere to treatment.

As mentioned above, Moulin et al (2017) demonstrated that the action of the Clinical Pharmacist through pharmacological follow-up improved adherence and reduced adverse effects. During the four months of follow-up, the researchers reduced the number of non-adherents from eight to zero, using the 4-item Morisky Therapeutic Adherence Scale. Furthermore, the number of patients complaining of ADR decreased from 35% to 7%.

Although the duration of the studies and the number of individuals evaluated were relatively small, the results are promising. Moreover, it is necessary a more accurate study in relation to the number of people and follow-up for longer periods.

In counter-match, a study covering 63 countries and 2546 patients found that it is not the fact that the patient experiences ADR that influences adherence, but rather how well the management of these is performed by the multidisciplinary team (GEISSLER et al., 2017).

In view of these results, we found evidence that the best way to promote treatment adeforego is to circumvent adverse events or even if possible to avoid possible future adverse events to promote better treatment. These are the reasons why we insert in the form questions about the main ADR described for Imatinib’s Mesysate, the intensity and time that the patient experiences them and feels the need for treatment. Thus, we hope to identify and circumvent the main undesirable effects related to medication, to promote greater safety, support and increase the quality of life of patients.

Although the strategy chosen to evaluate and improve adherence and reduce patients’ ADR is the form, Geissler et al (2017) found that an important factor that affects adherence and can be influenced by health professionals is patient information about CML. In this study, patients who felt better informed about the disease were significantly more adherent. Thus, two questions were inserted in our form to evaluate the patient’s knowledge of the disease/treatment and thus, with the participation of the multidisciplinary team, to plan complementary strategies. Still with this information, it is expected to integrate the patient more actively in the treatment emphasizing the information and not only in the instruction that it should follow.

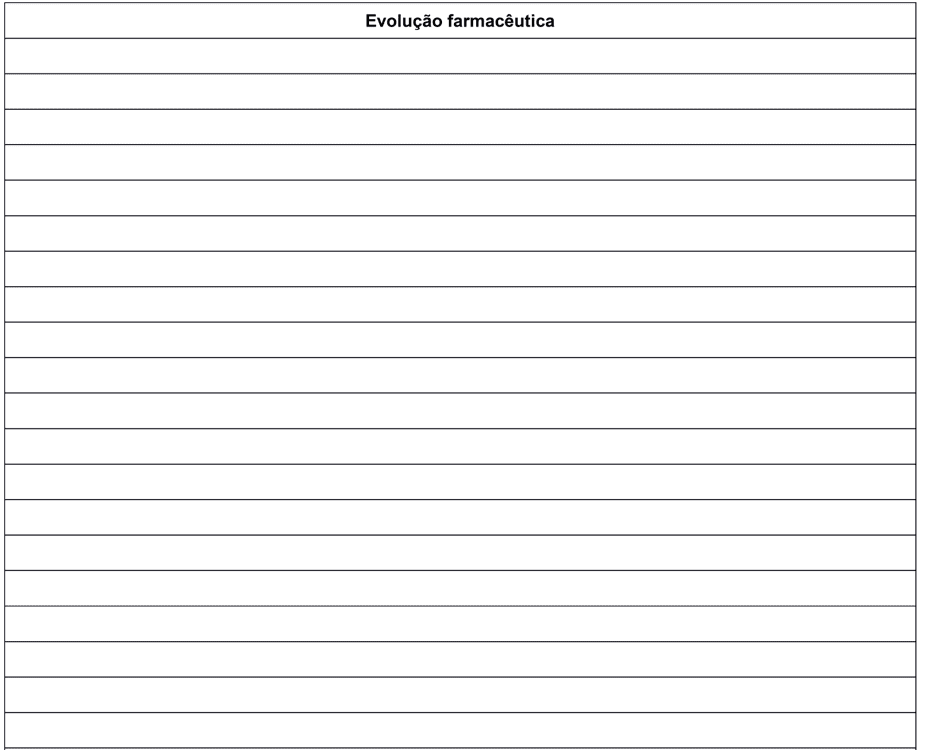

During the preparation of the form it was not possible to anticipate any situations or ADR that patients could report. That said, the back of the form was used for the field “Pharmaceutical Evolution” where they can be noted for example: subjective data, objective data, evaluation and specific planning for the evaluated patient.

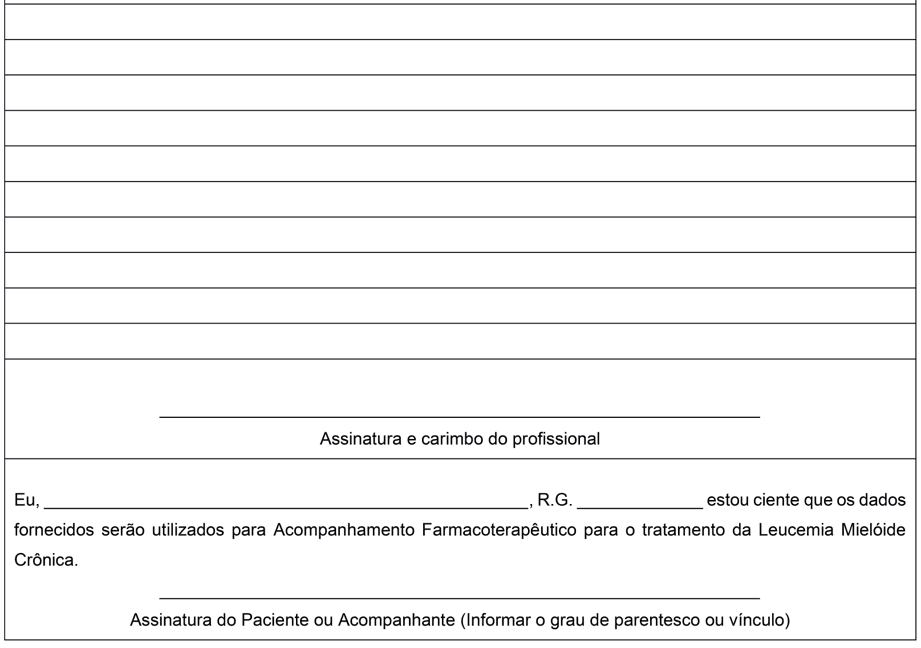

The proposal to construct the form model for application in patients with CML aims to improve the response to treatment with Imatinib Mesirate and quality of life. Thus, to date, there is no intention to incorporate the results of this activity into a research project. Therefore, no Terms of Clarification and Consent or any other document were produced to comply with Resolution No. 510 of April 7, 2016 of the Ministry of Health. This resolution provides for research whose methodological procedures involve the use of data directly obtained from participants or identifiable information (BRASIL, 2016). However, a text to be signed by the patient or his representative is placed on the back of the form stating that he/she is aware that the data provided will be used for Pharmacotherapeutic Follow-up of the treatment of Chronic Myeloid Leukemia.

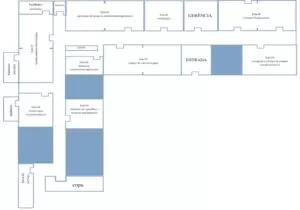

Annex I – Pharmaceutical follow-up form in adult patients with CML.

CONCLUSION

It is known that several factors serve as barriers to non-treatment to pharmacological treatment, such as: adverse events, daily routine of medication, feeling well without treatment, inadequate information about the medication. However, in particular in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia, non-treatment with Imatinib Mesilate may result in potential life-threatening treatment, since the outcome of this disease is well known and documented. Therefore, it is essential to frequentfollow up by the clinical pharmacist to identify early factors that may contribute negatively, facilitating the planning of interventions in order to promote better adherence and consequently achieve therapeutic goals.

To this end, a viable and low-cost strategy is the implementation of a follow-up form to be applied by the pharmacist at the time of dispensation. Thus, the standardized documentation of the care provided will serve not only to optimize pharmacotherapy, but also to increase patient safety, contributing to the development of actions aimed at the evolution of the patient, making more effective communication between multidisciplinary teams and assisting in the implementation of continuous improvements in order to maximize the quality of care provided to patients.

REFERENCES

ANDERSON, Kristin R. et al. Medication adherence among adults prescribed imatinib, dasatinib, or nilotinib for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia. Journal of Oncology Pharmacy Practice, v. 21, n. 1, p. 19-25, 2015.

BAGNYUKOVA, Tetyana V. et al. Chemotherapy and signaling: How can targeted therapies supercharge cytotoxic agents?. Cancer biology & therapy, v. 10, n. 9, p. 839-853, 2010.

BORTOLHEIRO, Teresa C; CHIATTONE, Carlos S. Leucemia mielóide crônica: história natural e classificação. Revista Brasileira de Hematologia e Hemoterapia, v. 30, p. 3-7, 2008.

BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde (MS). Resolução nº 510, de 7 de abril de 2016. Disponível em: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/cns/2016/res0510_07_04_2016.html. Acessado em: 23 de maio de 2020.

BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde (MS). Portaria nº 1.219, de 4 de novembro de 2013. Disponível em: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/sas/2013/prt1219_04_11_2013.html. Acessado em: 23 de maio de 2020.

BRAY, Freddie et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians, v. 68, n. 6, p. 394-424, 2018.

BRECCIA, Massimo et al. Adherence and future discontinuation of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in chronic phase chronic myeloid leukemia. A patient-based survey on 1133 patients. Leukemia research, v. 39, n. 10, p. 1055-1059, 2015.

CALADO, Deysiane Santos; TAVARES, Diego de Hollanda Cavalcanti; BEZERRA, Grasiela Costa. O papel da atenção farmacêutica na redução das reações adversas associados ao tratamento de pacientes oncológicos. Revista Brasileira de Educação e Saúde, v. 9, n. 3, p. 94-99, 2019.

CHABNER BA, ROBERTS TG Jr. Timeline: chemotherapy and the war on cancer. Nat Rev Cancer, v. 5, p. 65-72, 2005.

DI FELICE, Enza et al. The impact of introducing tyrosine kinase inhibitors on chronic myeloid leukemia survival: a population-based study. BMC cancer, v. 18, n. 1, p. 1069, 2018.

DREWS, Jürgen. Case histories, magic bullets and the state of drug discovery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery, v. 5, n. 8, p. 635-640, 2006.

FLIS, Sylwia; CHOJNACKI, Tomasz. Chronic myelogenous leukemia, a still unsolved problem: pitfalls and new therapeutic possibilities. Drug design, development and therapy, v. 13, p. 825, 2019.

GEISSLER, Jan et al. Factors influencing adherence in CML and ways to improvement: Results of a patient-driven survey of 2546 patients in 63 countries. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology, v. 143, n. 7, p. 1167-1176, 2017.

HEFNER J, CSEF EJ, KUNZMANN V. Fear of progression in outpatients with chronic myeloid leukemia on oral tyrosine kinase inhibitors. In: Oncology Nursing Forum. Oncology Nursing Society, 2016. p. 190.

HOSOYA, Kazuhisa et al. Failure mode and effects analysis of medication adherence in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia. International journal of clinical oncology, v. 20, n. 6, p. 1203-1210, 2015.

Instituto Nacional de Câncer Jose Alencar Gomes da Silva. ABC do câncer: abordagens básicas para o controle do câncer, 5. ed. Rio de Janeiro: INCA, 2019.

Instituto Nacional de Câncer Jose Alencar Gomes da Silva. Estimativa 2018: incidência de câncer no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro, 2017. Disponível em: https://www.inca.gov.br/sites/ufu.sti.inca.local/files//media/document//estimativa-incidencia-de-cancer-no-brasil-2018.pdf. Acesso em: 08 out. 2019.

JULIUSSON, G.; HOUGH, R. Leukemia. Prog Tumor Res 2016; 43: 87–100. Google Scholar| Crossref| Medline.

KEKÄLE, Meri et al. Impact of tailored patient education on adherence of patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia to tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a randomized multicentre intervention study. Journal of advanced nursing, v. 72, n. 9, p. 2196-2206, 2016.

LATREMOUILLE-VIAU, Dominick et al. Health care resource utilization and costs in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia with better adherence to tyrosine kinase inhibitors and increased molecular monitoring frequency. Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy, v. 23, n. 2, p. 214-224, 2017.

LIU, Tao; PENG, Xing-Chun; LI, Bin. The Metabolic Profiles in Hematological Malignancies. Indian Journal of Hematology and Blood Transfusion, p. 1-10, 2019.

MOULIN, Silmara Mendes Martins et al. The role of clinical pharmacists in treatment adherence: fast impact in suppression of chronic myeloid leukemia development and symptoms. Supportive Care in Cancer, v. 25, n. 3, p. 951-955, 2017.

MULU FENTIE, Atalay et al. Prevalence and determinants of non-adherence to Imatinib in the first 3-months treatment among newly diagnosed Ethiopian’s with chronic myeloid leukemia. PloS one, v. 14, n. 3, p. e0213557, 2019.

MULUNEH, Benyam et al. Patient perspectives on the barriers associated with medication adherence to oral chemotherapy. Journal of Oncology Pharmacy Practice, v. 24, n. 2, p. 98-109, 2018.

Novartis Biociências S.A. Bula do medicamento Glivec®. Disponível em: https://portal.novartis.com.br/UPLOAD/ImgConteudos/1821.pdf. Acessado em: 20 de agosto de 2020.

RYCHTER, Anna et al. Treatment adherence in chronic myeloid leukaemia patients receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Medical Oncology, v. 34, n. 6, p. 104, 2017.

SACHDEVA, Ashwani et al. Association of leukemia and mitochondrial diseases—A review. Journal of family medicine and primary care, v. 8, n. 10, p. 3120, 2019.

SAUSSELE, Susanne et al. Defining therapy goals for major molecular remission in chronic myeloid leukemia: results of the randomized CML Study IV. Leukemia, v. 32, n. 5, p. 1222-1228, 2018.

SIEGEL, Rebecca L.; MILLER, Kimberly D.; JEMAL, Ahmedin. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians, v. 69, n. 1, p. 7-34, 2019.

SOUZA, Jessica de O. et al. Adherence to TKI in CML patients: more than reports. Supportive Care in Cancer, v. 26, n. 2, p. 325-326, 2018.

TAN, Bee Kim et al. Efficacy of a medication management service in improving adherence to tyrosine kinase inhibitors and clinical outcomes of patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia: a randomised controlled trial. Supportive Care in Cancer, p. 1-11, 2019.

THAVAMANI B. Samuel; MATHEW, Molly; DHANABAL, S. P. Anticancer activity of cissampelos pareira against dalton’s lymphoma ascites bearing mice. Pharmacognosy magazine, v. 10, n. 39, p. 200, 2014.

TRIVEDI, Digisha et al. Adherence and persistence among chronic myeloid leukemia patients during second-line tyrosine kinase inhibitor treatment. Journal of Managed Care Pharmacy, v. 20, n. 10, p. 1006-1015, 2014.

TSAI, Yu-Fen et al. Side effects and medication adherence of tyrosine kinase inhibitors for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in Taiwan. Medicine, v. 97, n. 26, 2018.

UNNIKRISHNAN, Radhika et al. Comprehensive evaluation of adherence to therapy, its associations, and its implications in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia receiving imatinib. Clinical Lymphoma Myeloma and Leukemia, v. 16, n. 6, p. 366-371. e3, 2016.

WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION et al. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. World Health Organization, 2003.

[1] Pharmacist. Specialist in Clinical and Hospital Pharmacy, Senac. Multiprofessional Oncology Specialist (HIAE).

[2] Pharmaceutical. Specialist in Clinical and Hospital Pharmacy, Senac.

[3] Pharmacist. Specialist in Clinical and Hospital Pharmacy, Senac.

[4] Pharmaceutical. Specialist in Clinical and Hospital Pharmacy, Senac.

[5] Pharmacist. Master in Medical Sciences, FMUSP. Multiprofessional Oncology Specialist (HSL). Specialist in Hospital Pharmacy (FOC).

Submitted: August, 2020.

Approved: October, 2020.