ORIGINAL ARTICLE

FACCO, Lucas [1], ALMENDRO, Lucas Pablo [2], MARQUES, Cristiane Peres [3], RIBEIRO, Edson Fábio Brito [4], FECURY, Amanda Alves [5], DENDASCK, Carla Viana [6], ARAÚJO, Maria Helena Mendonça de [7], OLIVEIRA, Euzébio de [8], DIAS, Claudio Alberto Gellis de Mattos [9]

FACCO, Lucas. Et al. Malignant testicular neoplasia: epidemiological analysis of cases reported in Brazil between 2015 and 2019. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year. 06, Ed. 10, Vol. 07, pp. 62-74. October 2021. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access Link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/health/testicular-neoplasia, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/health/testicular-neoplasia

SUMMARY

Testicular neoplasia is a relatively uncommon malignant pathology, representing 0.5% of all male neoplasms, being more frequent among individuals aged 15 to 34 years. The most common clinical presentation is testicular mass or scrotal swelling with or without associated pain or trauma, and the standard confirmatory diagnosis is orchiectomy. This study aimed to epidemiologically analyze the reported cases of malignant testicular neoplasia in Brazil between 2015 and 2019. Data for epidemiological research were obtained from DATASUS and bibliographic research was carried out through scientific articles. From the information revealed in this research, it is possible to observe an increasing diagnosis of malignant neoplasm of the testicles in Brazil, with almost twice the number of cases observed between the years 2015 and 2019. Although relatively uncommon, testicular cancer is potentially deadly and its severity should not be underestimated and should be diagnosed and treated as early as possible. It has a high chance of cure, with definitive surgical treatment, after a confirmatory diagnosis, in most cases, allowing the affected individual to have a normal life. Thus, more studies are needed to reveal the reasons for the increase in cases of testicular cancer in Brazil and worldwide, to understand whether regional differences are related to the number of cases or whether it is a failure in diagnosis and registration, as well as serving as a basis for actions of the government, in order to plan and execute policies aimed at combating the triggering factors of this disease.

Keywords: Malignant neoplasms, Urological tumors, Testicular cancer, Inguinal orchiectomy, Epidemiology.

INTRODUCTION

Cancer or neoplasia occurs by the proliferation of cells of the organism that present morphological and functional changes and cause tissue disorder. Such changes may have genetic or environmental causes (Dias et al., 2017).

Testicular neoplasia is a relatively uncommon malignant pathology, representing 0.5% of all male neoplasms and 5% of urological tumors (Rosen et al., 2011; Nci, 2021), and is more frequent among individuals aged 15 to 34 years (Baird et al., 2018). In addition, the most common variant was germ cell tumor, with 95% of cases, and the most frequent diagnosis in clinically localized stage I palpable masses (Adra and Einhorn, 2017; Pierorazio et al., 2018).

Risk factors for the development of this type of cancer were pointed out: previous history, with a risk of 5 to 6% of overcoming the contralateral testicle; family history, with a risk of 8 to 10 times among siblings and 4 to 6 times among children of a carrier; cryptorchidism, with odds ratio (OR) 4.3, 95% confidence interval 3.6-5.1; late orchidopexy (testicular fixation in the scrotal stalk) with OR of 5.8 when compared with early; and Klinefelter syndrome (Hemminki and Li, 2004; Walsh et al., 2007; Cook et al., 2010; Lip et al., 2012; Chan et al., 2014; Kier et al., 2016; Nery, 2019). The most common clinical presentation is testicular mass or scrotal swelling with or without associated pain/trauma, having as differential diagnosis orchitis or epididymitis, can then start treatment with antibiotics (Nery, 2019). Metastases may occur, depending on location, such as: gastrointestinal symptoms; gynecomastia; headache; low back pain; neck mass; symptoms (dyspnea, cough and hemoptysis) (Shaw, 2008).

The diagnostic methodology for such neoplasia begins during the physical examination, with the palpation of the scrotal stalk, but this generates ambiguous results, so the use of radiological investigation with transscrotal ultrasonography, which has been noted the increasing use in the detection of impalpable or ambiguous lesions (Dieckmann et al., 2013; Cheng et al., 2018). The standard confirmatory diagnosis is radical orchiectomy (surgery to remove one or both testicles and the entire spermatic cord), which makes it possible to establish the character and often already used with treatment (Ghoreifi and Djaladat, 2019). The gold standard treatment for testicular masses with suspected malignancy, with no signs of metastases, was established as radical orchiectomy with removal up to the level of the internal inguinal ring, which is often performed during a diagnostic procedure and offered the possibility of replacement by testicular prosthesis (Krege et al., 2008; Robinson et al., 2015; Ghoreifi e Djaladat, 2019). Nevertheless, serum tumor markers (alpha-fetoprotein – AFP – and human cationic beta-gonadotropin – Beta-HCG ) are used to assist to evaluate the effectiveness of treatment and assess the prognosis for the patient, since they must be established before and after treatment, as well as during surveillance period (Gilligan et al., 2019).

In the global context, there were 72,000 diagnoses and 9,000 deaths per year for this neoplastic process, and the risk of a man developing testicular cancer during some time in his life was estimated as 1 in 250 men (Fitzmaurice et al., 2017; Acs, 2021). The estimated projection for 2021 of new cases of testicular cancer in the United States of America was 9,470 diagnoses and 440 deaths, in addition to a higher frequency among white individuals (6.9 individuals affected by 100,000 men) compared to African-Americans (1.2 individuals affected by 100,000 men) (Ghazarian et al., 2014; Acs, 2021).

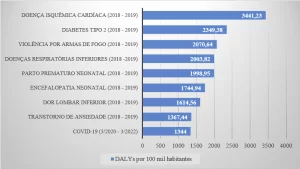

In turn, at the national level, there was a certain scarcity of epidemiological data on this neoplasm, but there was an increase in mortality when compared to the data from 2015 (359 deaths, representing 0.05% of the general mortality) and 2019 (446 deaths, representing 0.06% of the overall mortality) of the Atlas of Mortality from Cancer – Mortality Information System (Nery, 2019; Inca, 2021).

GOAL

Epidemiologically analyze the reported cases of malignant testicular neoplasia in Brazil between 2015 and 2019.

METHOD

The research used quali quantitative methodology (mixed method), with government data, because in addition to numerical data involved the interpretation of phenomena (Facco et al., 2021).

Datasus (datasus) database (http://datasus.saude.gov.br/). National data were collected according to the following steps: A) The datasus.saude.gov.br link was accessed, the arrow was slid with the mouse to the “Featured Services” tab, immediately after selecting the option “TABNET”; B) On the next page “TABNET” clicked on the option “Epidemiological and Morbidity” and therefore the option “Time to the beginning of cancer treatment – PANEL – oncology” was selected. From there, the steps were followed: A) In the box “Line”, “Year of diagnosis” was selected throughout the process; B) In the “Measures” box, “Cases” were selected throughout the process; C) And in the “Column” box, the following were selected: “Staging”, “Age Group”, “Therapeutic Modality”, “Treatment Time”, “UF of Residence”, “Uf of Diagnosis” and “UF of Treatment”. All data collected in the system covers the periods 2015 to 2019. D) In the “available selection” box in the “Diagnosis” option, the option “Malignant Neoplasms (Law no. 12,732/12) was selected and in “Detailed Diagnosis” the option “C62 Malignancy of the testicles” was selected. In the other available check boxes, the standard options of the DATASUS system were maintained. The data was compiled within the Excel application, a component of the Office suite of Microsoft Corporation, and the data from the regions of Brazil were agglutinated from the data provided by each of the states of the appropriate regions. The bibliographic research was carried out in scientific articles, using personal computers of the authors of the present study.

RESULTS

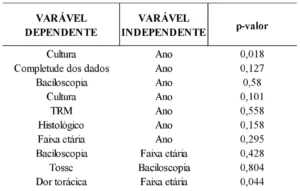

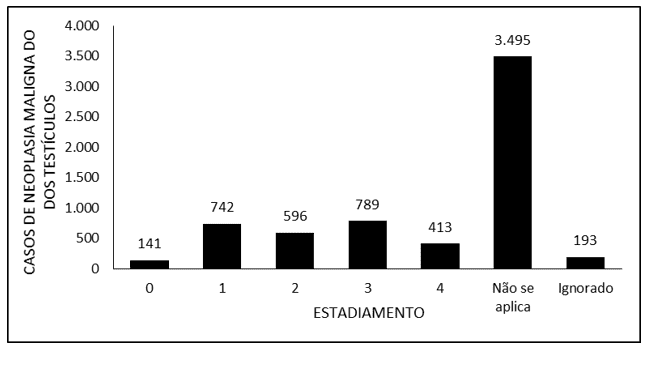

Figure 1 denotes the number of cases of malignant neoplasm of the testicles in Brazil between 2015 and 2019, through staging. It is noted that the grade 3 staging was the most comprehensive (789 cases), followed by grade 1 (742), grade 2 (596), and 0 (141). It is noticed that, in the vast majority of reported cases, the staging criterion was classified as “does not apply”, in addition to 193 cases were reported as “ignored”.

Figure 1 – Shows the number of cases of malignant neoplasm of the testicles in Brazil between 2015 and 2019, through staging.

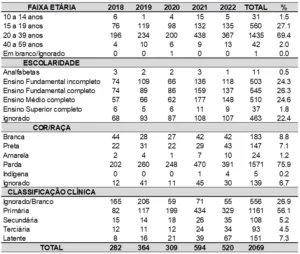

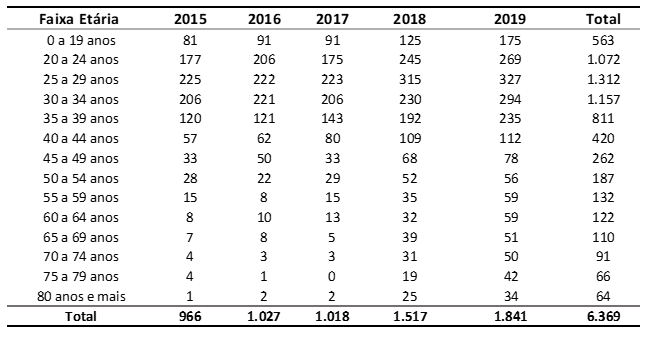

Table 1 denotes the number of cases of malignant neoplasm of the testicles in Brazil between the years 2015 and 2019, according to the age group. It is noted that the 5 age ranges with the highest number of reported cases of testicular malignancy are: 25 to 29 years (1,312), 30 to 34 years (1,157), 20 to 24 years (1,072), 35 to 39 years (811) and 0 to 19 years (563). In addition, it was noted that the highest number of reported cases occurred in 2019, with 1,841 cases.

Table 1 – Shows the number of cases of malignant neoplasm of the testicles in Brazil between the years 2015 and 2019, according to the age group.

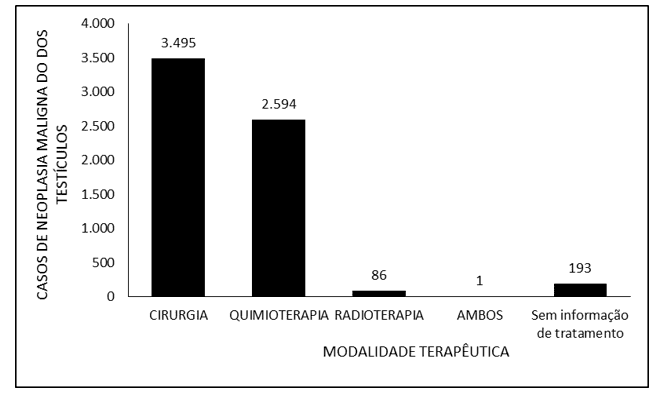

Figure 2 covers the number of cases of malignant neoplasm of the testicles in Brazil between 2015 and 2019, through the therapeutic modality used. It is noted that the largest proportion of patients (3,495) were treated surgically, and 2,594 were treated using chemotherapy. Radiotherapy was used in 86 patients and only 1 patient made use of the three therapeutic modalities. There was no information on the treatment used in 193 patients.

Figure 2 – Shows the number of cases of malignant neoplasm of the testicles in Brazil between 2015 and 2019, through the therapeutic modality.

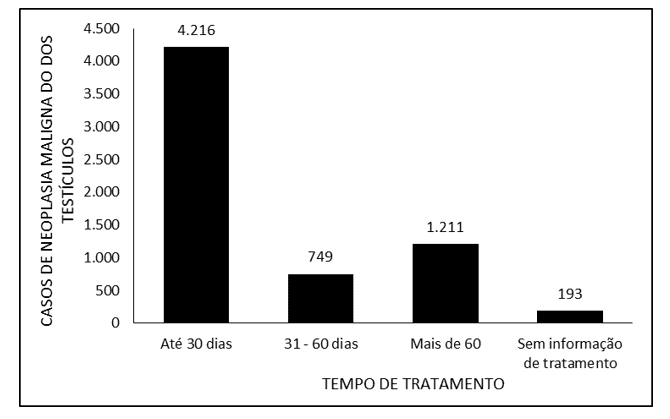

Figure 3 denotes the number of cases of malignant neoplasm of the testicles in Brazil between 2015 and 2019, through the time of treatment. The vast majority of reported cases refer to treatment time of up to 30 days (4,216), followed by more than 60 days (1,211) and 31 to 60 days (749). There was no information on the time of treatment for 193 patients.

Figure 3 – Shows the number of cases of malignant neoplasm of the testicles in Brazil between 2015 and 2019, through the time of treatment.

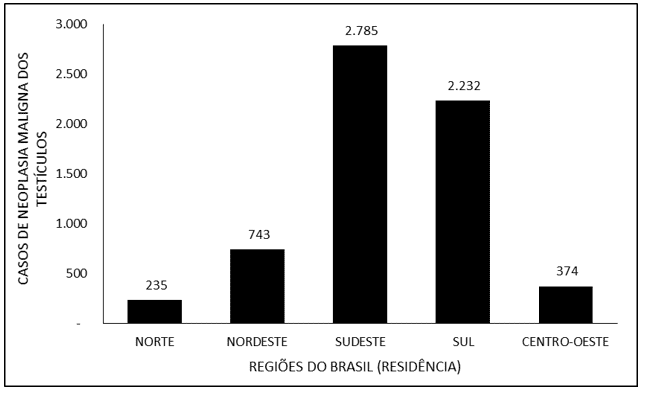

Figure 4 denotes the number of cases of malignant neoplasm of the testicles in Brazil between 2015 and 2019, through the region of residence. Most cases refer to the Southeast (2,785), followed by the South (2,232), Northeast (743), Midwest (374) and North (235) regions.

Figure 4 – Shows the number of cases of malignant neoplasm of the testicles in Brazil between 2015 and 2019, through the region of residence.

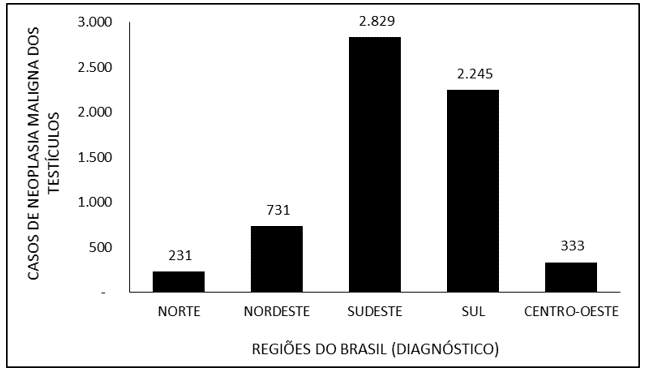

Figure 5 denotes the number of cases of malignant neoplasm of the testicles in Brazil between 2015 and 2019, through the region of diagnosis. It is noted that the largest share of diagnoses occurred in the Southeast (2,829), followed by the South (2,245), Northeast (731), Midwest (333) and North (231).

Figure 5 – Shows the number of cases of malignant neoplasm of the testicles in Brazil between 2015 and 2019, through the region of diagnosis.

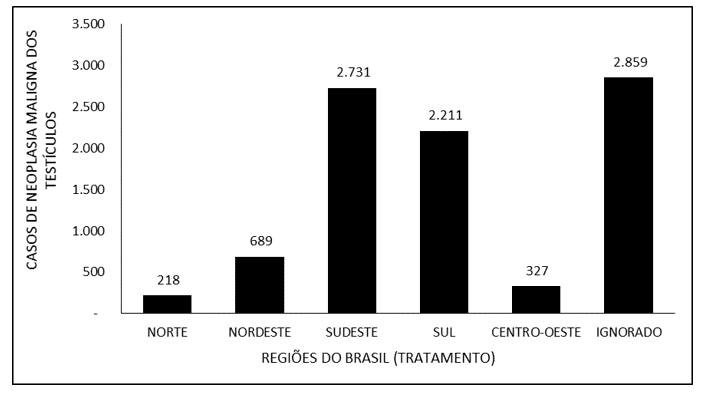

Figure 6 covers the number of cases of malignant neoplasm of the testicles in Brazil between 2015 and 2019, through the treatment region. Most cases (2,859) were reported as “ignored”. The Southeast region had the highest notification of treatments for testicular malignancy, with 2,731 notifications, followed by the South (2,211), Northeast (689), Midwest (327) and North (218).

Figure 6 – Shows the number of cases of malignant neoplasm of the testicles in Brazil between 2015 and 2019, through the treatment region.

DISCUSSION

As can be seen in Table 1, there was an increasing increase in the number of cases of malignant testicular neoplasia in Brazil between 2015 and 2019, following the worldwide trend that, for decades, has been increasing the incidence rate of testicular cancer in many countries. However, the reasons for this phenomenon are still unknown (Acs, 2021).

The high number of diagnoses of malignant neoplasm of the testicles at stage 3 may be based on the silent evolution of a painless solid mass, which is often poorly evaluated and diagnosed as orchitis or epididymitis, which ends up being treated inappropriately (benignly), generating a delay in the correct approach, which can be up to 20 weeks, enabling the emergence of metastases (Moul, 2007; Shaw, 2008; Nery, 2019). These, in turn, present clinical symptoms, thus allowing the diagnosis of the neoplastic and metastatic process already present, such as respiratory symptoms (dyspnea, cough and hemoptysis) (Shaw, 2008).

As has been illustrated in other studies, the most common age group for developing testicular cancer was 15 to 34 years, thus corroborating the data presented in this study (Baird et al., 2018). In addition, factors that may have led to the detection of neoplasia in this age group may be early sexarche and active sexual life, which allow greater body self-knowledge and multiple sexual partners, which allows earlier to notice the formation of a scrotal edema of unknown cause and consequent search for medical care (Adra and Einhorn, 2017). It is important to mention that testicular cancer screening is not recommended, since there is evidence that its practice brings more benefits than risks (Inca, 2021).

The surgical procedure was established as the gold standard treatment, as it removes the neoplastic focus from the spermatic cord to the level of the lower inguinal ring, sparing excessive manipulation of the lymph node chain and the neoplastic focus itself, thus avoiding cellular extravasation of the cancerous process (Krege et al., 2008; Rajpert-De-Meyts et al., 2016; Ghoreifi e Djaladat, 2019; Eau, 2021).

A justification for treatment with triple modality is the presence of distant metastasis, which makes it necessary to use chemotherapy and radiotherapy together with the surgical procedure, increasing survival to 96% in 10 years (Nery, 2019; Nci, 2021), varying the combinations and cycles of chemoradiotherapy according to the clinical stage and individual variables,such as 4 cycles of BEP (Cisplatin 20 mg/m2 , intravenous on day 1 to day 5; Etoposide 100 mg/m2, intravenous on day 1 to day 5; Bleomycin 30 iu intravenous on days 2, day 9 and day 16; Repeat every 21 days) (Nery, 2019).

It is understood that, often, during the confirmatory diagnostic process, inguinal orchiectomy is chosen, which is considered a therapeutic procedure, since it removes the primary focus of neoplasia (Ghoreifi and Djaladat, 2019). In addition, we have to at the time of the formulation of diagnostic hypothesis with radiological examinations and choice for radical orchiectomy up to the level of the lower inguinal ring, and replacement by prosthesis it is necessary to investigate the surgical risk and whether there are metastatic foci in other regions by means of tumor markers. (Krege et al., 2008; Robinson et al., 2015; Ghoreifi e Djaladat, 2019; Gilligan et al., 2019).

Considering that 49.5% of the hospitals qualified for the management of neoplastic processes are located in the Southeast region of the country, followed by the South region, with 24.2%, and that both are have greater availability of recognition units, it is possible to infer that they also have a better system for diagnostic recognition of this neoplasm. In addition, the highest treatment rates are located in the South and Southeast regions of Brazil, with 37.9% of all diagnoses recorded only in the state of São Paulo (Inca, 2019a; 2019b; 2019c; 2019d; 2019e; 2019f; 2019g; 2019h).

Testicular cancer is a malignant neoplasm that affects a considerable number of young adults with active sexual life and that can lead to death (Park et al., 2018). However, it represents one of the most curable malignancies when readily identified and treated with a multimodal approach. With effective management, the prognosis is excellent, with cure rate> 90% and five-year survival rate> 95% (Smith et al., 2018).

CONCLUSION

From the information revealed in this research, it is possible to observe an increasing diagnosis of malignant neoplasm of the testicles in Brazil, with almost twice the number of cases observed between the years 2015 and 2019. Although relatively uncommon, testicular cancer is potentially deadly and its severity should not be underestimated and should be diagnosed and treated as early as possible. It has a high chance of cure, with definitive surgical treatment, after a confirmatory diagnosis, in most cases, allowing the affected individual to have a normal life. Thus, more studies are needed to reveal the reasons for the increase in cases of testicular cancer in Brazil and worldwide, to understand whether regional differences are related to the number of cases or whether it is a failure in diagnosis and registration, as well as serving as a basis for actions of the government, in order to plan and execute policies aimed at combating the triggering factors of this disease.

REFERENCES

ACS. Key Statistics for Testicular Cancer. New York NY, 2021. Disponível em: < https://www.cancer.org/cancer/testicular-cancer/about/key-statistics.html#references >. Acesso em: 05 mar 2021.

ADRA, N.; EINHORN, L. H. Testicular Cancer Update. Clinical Advances in Hematology & Oncology, v. 15, n. 5, p. 386-396, 2017.

BAIRD, D. C.; MEYERES, G.; HU, J. S. Testicular Cancer: Diagnosis and Treatment. American Family Physician, v. 97, n. 4, p. 261-268, 2018.

CHAN, E.; WAYNE, C.; NASR, A. Ideal timing of orchiopexy: a systematic review. Pediatric Surgery International, v. 30, n. 1, p. 87–97, 2014.

CHENG, L. et al. Testicular cancer. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, v. 4, n. 29, p. 1-24, 2018.

COOK, M. B. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of perinatal variables in relation to the risk of testicular cancer—experiences of the son. International Journal of Epidemiology, v. 39, n. 6, p. 1605-1618, 2010.

DIAS, A. D. A. et al. Update on the Main Aspects Related to Breast Cancer. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento, v. 4, p. 5-17, 2017. Disponível em: < https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/health/breast-cancer >.

DIECKMANN, K. P.; FREY; LOCK, G. Contemporary diagnostic work-up of testicular germ cell tumours. Nat Rev Urol v. 10, p. 703–712, 2013.

EAU. Testicular Cancer. Düsseldorf DE, 2021. Disponível em: < https://uroweb.org/guideline/testicular-cancer/#1 >. Acesso em: 06 mar 2021.

FACCO, L. et al. Neoplasia maligna de esôfago: uma análise epidemiológica dos casos notificados no Brasil entre 2015 e 2019. Research, Society and Development, v. 10, n. 2, p. 1-14, 2021. Disponível em: < https://rsdjournal.org/index.php/rsd/article/view/12750/11622 >.

FITZMAURICE, C. et al. Global, Regional, and National Cancer Incidence, Mortality, Years of Life Lost, Years Lived With Disability, and Disability-Adjusted Life-years for 32 Cancer Groups, 1990 to 2015: A Systematic Analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. .JAMA Oncol, v. 3, n. 4, p. 524-548, 2017.

GHAZARIAN, A. A. et al. Recent trends in the incidence of testicular germ cell tumors in the United States. Andrology, v. 3, n. 1, p. 13–18, 2014.

GHOREIFI, A.; DJALADAT, H. Management of Primary Testicular Tumor. Urologic Clinics of North America, v. 46, n. 3, p. 333–339, 2019.

GILLIGAN, T. et al. Testicular Cancer, Version 2.2020, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, v. 17, n. 12, p. 1529-1554, 2019.

HEMMINKI, K.; LI, X. Familial risk in testicular cancer as a clue to a heritable and environmental aetiology. British Journal of Cancer, v. 90, n. 9, p. 1765–1770, 2004.

INCA. Onde tratar pelo SUS. Brasília DF, 2019a. Disponível em: < https://www.inca.gov.br/onde-tratar-pelo-sus#:~:text=Existem%20atualmente%20317%20unidades%20e,exame%20até%20cirurgias%20mais%20complexas >. Acesso em: 06 mar 2021.

______. Paraná. Brasília DF, 2019b. Disponível em: < https://www.inca.gov.br/onde-tratar-pelo-sus/parana >. Acesso em: 06 mar 2021.

______. Santa Catarina. Brasília DF, 2019c. Disponível em: < https://www.inca.gov.br/onde-tratar-pelo-sus/santa-catarina >.

______. Rio Grande do Sul. Brasília DF, 2019d. Disponível em: < https://www.inca.gov.br/onde-tratar-pelo-sus/rio-grande-sul >. Acesso em: 06 mar 2021.

______. Minas Gerais. Brasília DF, 2019e. Disponível em: < https://www.inca.gov.br/onde-tratar-pelo-sus/minas-gerais >. Acesso em: 12 jan 2021.

______. São Paulo. Brasília DF, 2019f. Disponível em: < https://www.inca.gov.br/onde-tratar-pelo-sus/sao-paulo >. Acesso em: 15 jan 2021.

______. Rio de Janeiro. Brasília DF, 2019g. Disponível em: < https://www.inca.gov.br/onde-tratar-pelo-sus/rio-janeiro >. Acesso em: 15 jan 2021.

______. Espírito Santo. Brasília DF, 2019h. Disponível em: < https://www.inca.gov.br/onde-tratar-pelo-sus/espirito-santo >. Acesso em: 01 jul 2021.

______. Câncer de testículo. Brasilia DF, 2021. Disponível em: < https://www.inca.gov.br/tipos-de-cancer/cancer-de-testiculo >. Acesso em: 06 mar 2021.

KIER, M. G. et al. Second Malignant Neoplasms and Cause of Death in Patients With Germ Cell Cancer. JAMA Oncology, v. 2, n. 12, p. 1624–1627, 2016.

KREGE, S. et al. European consensus conference on diagnosis and treatment of germ cell cancer: a report of the second meeting of the European Germ Cell Cancer Consensus group (EGCCCG): part I. Eur Urol v. 53, n. 3, p. 478–496, 2008.

LIP, S. Z. L. et al. A meta-analysis of the risk of boys with isolated cryptorchidism developing testicular cancer in later life. Archives of Disease in Childhood, v. 98, n. 1, p. 20–26, 2012.

MOUL, J. W. Diagnosis of Testicular Cancer. Urologic Clinics of North America, v. 34, n. 2, p. 109–117, 2007.

NCI. Cancer Stat Facts: Testicular Cancer. USA, 2021. Disponível em: < https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/testis.html >. Acesso em: 03 mar 2021.

NERY, R. C. Câncer de Testículo. In: SANTOS, M. (Ed.). Diretrizes oncológicas 2. São Paulo SP: Doctor Press Ed. Científica, 2019.

PARK, J. S. et al. Recent global trends in testicular cancer incidence and mortality. Medicine, v. 97, n. 37, p. 1-7, 2018. Disponível em: < https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6155960 >.

PIERORAZIO, P. M. et al. Non–risk-adapted Surveillance for Stage I Testicular Cancer: Critical Review and Summary. European Urology, v. 73, n. 6, p. 899–907, 2018.

RAJPERT-DE-MEYTS, E. et al. Testicular germ cell tumours. The Lancet, v. 387, n. 10029, p. 1762–1774, 2016.

ROBINSON, R. et al. Is it safe to insert a testicular prosthesis at the time of radical orchidectomy for testis cancer: an audit of 904 men undergoing radical orchidectomy. BJU International, v. 117, n. 2, 2015.

ROSEN, A. et al. Global Trends in Testicular Cancer Incidence and Mortality. European Urology, v. 60, n. 2, p. 374–379, 2011.

SHAW, J. Diagnosis and Treatment of Testicular Cancer. American Family Physician, v. 7, n. 4, p. 469-474, 2008.

SMITH, Z. L.; WERNTZ, R. P.; EGGENER, S. E. Testicular Cancer: Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Management. Medical Clinics of North America, v. 102, n. 2, p. 251-264, 2018. Disponível em: < https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0025712517301578?via%3Dihub >.

WALSH, T. J. et al. Prepubertal Orchiopexy for Cryptorchidism May be Associated With Lower Risk of Testicular Cancer. The Journal of Urology, v. 178, n. 4, p. 1440–1446, 2007.

[1] Student of the Medical Course of the Federal University of Amapá (UNIFAP).

[2] Student of the Medical Course of the Federal University of Acre (UFAC).

[3] Student of the Production Engineering Course of the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS).

[4] Student of the Medical Course of the Federal University of Amapá (UNIFAP).

[5] Biomedical, PhD in Tropical Diseases, Professor and researcher of the Medical Course of the Federal University of Amapá (UNIFAP).

[6] Theologian, PhD in Clinical Psychoanalysis. She has been working for 15 years with Scientific Methodology (Research Method) in Scientific Production Guidance for Masters and Doctoral Students. Specialist in Market Research and Health Research. Doctoral Student in Communication and Semiotics (PUC SP).

[7] Doctor, Master in Teaching and Health Sciences, Professor and researcher of the Medical Course of Macapá Campus, Federal University of Amapá (UNIFAP).

[8] Biologist, PhD in Tropical Diseases, Professor and researcher of the Physical Education Course, Federal University of Pará (UFPA).

[9] Biologist, PhD in Theory and Behavior Research, Professor and researcher of the Graduate Program in Professional and Technological Education (PROFEPT), Federal Institute of Amapá (IFAP).

Submitted: October, 2021.

Approved: October, 2021.