ORIGINAL ARTICLE

CAPIÑALA, Henriques Tchinjengue [1], BETTENCOURT, Miguel Santana [2]

CAPIÑALA, Henriques Tchinjengue. BETTENCOURT, Miguel Santana. Socioeconomic impact of stroke in patients and family members. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 05, Ed. 10, Vol. 13, pp. 05-40. October 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access Link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/health/stroke, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/health/stroke

SUMMARY

Introduction: Stroke is a worldwide public health problem and one of the major causes of acquired disability worldwide. Objective: To study the socioeconomic weight of stroke in patients and family members, followed by an external consultation of Neurology at Hospital Américo Boavida (HAB) and at the Center for Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation of Luanda (CMFRL) from June to August 2013. Methods: A cross-sectional descriptive observational study of 56 patients after stroke, assisted in the HAB and CMFRL/2013, was conducted. The sample was non-probabilistic, convenience-type. The data were collected using a form as well as the Barthel Index (IB) to assess the degree of functional dependence. Results: The mean age was 53 years, since the modal age group was 50-59 years, the male gender was the most frequent (53.6%), the majority of patients were married (69.6%), unemployed (25%), with primary education done (37.5%); 80.4% go to public transport consultation, the majority reported being taken care of by the spouse (67.9%), so 100% of the unemployed was due to their illness; 50% reported having households consisting of 6-8 people; the most frequent monthly income was 2-5 minimum wages (47%), and more was spent on complementary diagnostic tests with an average of 9,844.6 4 Kz/month and a total expenditure on average of 28510.71 Kz/month and that 25% of the sample spent more than 50% of the monthly income for the disease; 44.6% was moderately dependent. Finally, it was found that most of those who had some degree of dependence became unemployed and spent more than 50% of the monthly household income for the disease. Conclusion: Stroke affects, often the most deprived people and, at the same time, contributes even more to socioeconomic deprivation.

Key Words: Stroke, Impact, socioeconomic.

INTRODUCTION

STROKE CONCEPT

Stroke is defined as a set of signs and symptoms that last at least 24 hours and result from brain damage caused by changes in blood irrigation. (HARRISON et. al., 2008; GOMES, 2003; ANTÓNIO, 2011; PIRES, 2004; RODGERS, 2004; PEREIRA, 2001; NICOLETTI et. al., 2000)

EPIDEMIOLOGY

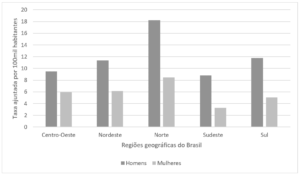

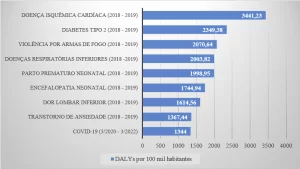

Stroke is a worldwide public health problem, one of the major causes of acquired disability worldwide (CORREIA, 2006; CABRAL et. al., 2013) . The world prevalence in the general population is estimated at 0.5% to 0.7% and is considered the third leading cause of death after heart and cancer diseases (CABRAL et. al., 2013; CHAGAS and MONTEIRO, 2013). Each year, 15 million people suffer from stroke. Of them 5 million die and 5 million are left with permanent disability, imposing a heavy burden on individuals, families and the community (LOGEN, 2003; ANTONIO, 2011). Mortality varies considerably in relation to the degree of socioeconomic development, with about 85% occurring in underdeveloped or developing countries and one third of cases reach the economically active portion of the population. (CORREIA, 2006) In the American continent the mortality rate was estimated at 59 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants. Approximately 730,000 Americans have a new stroke or recurrence each year. Recent data suggest an increase in incidence. This impact is expected to increase in the coming decades, as an increase of 300‰ in the elderly population is expected in developing countries over the next 30 years, especially in Latin America and Asia (SILVA and COSTA, 2012). Brazil is the 6th country in number of strokes, after China, India, Russia, the United States and Japan. Among Latin American countries, it is the country with the highest mortality from stroke in both men and women. (Sá, 2013) According to the Brazilian Ministry of Health, stroke is the leading cause of death in Brazil (PADILHA, 2011) There are large geographical, ethnic, cultural and socioeconomic differences regarding the incidence of stroke in the neighborhoods of the city of São Paulo and Salvador (LOGEN, 2003; GOMES, 2003). In Europe it is estimated that the mortality rate from stroke is 115 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants (SILVA and COSTA, 2012). Official statistics show that Portugal has the highest stroke mortality rate among western European countries, where it is the leading cause of death. It is the second country with the highest prevalence among all european countries, ranging from 1 to 2 cases per 1000 inhabitants (ABE, 2010; PADILHA, 2011) . In which it can be said that it is calculated that six people, in each hour, suffer a stroke, and that two to three die as a result of this disease, according to SPAVC (Portuguese Society of Stroke) (ABE, 2010; SILVA and COSTA, 2012) .

The O.M.S. in its global burden of disease program, published in 2008, presents results based on estimates, two of which state that more than 85% of strokes occur in countries with lower resources, compared to rich countries where they make considerable preventive interventions to reduce the occurrence of stroke corresponding, globally, to 10% of all deaths (PADILHA , 2011). More recent studies reveal that the most fatal cases of stroke are more frequent in sub-Saharan Africa (ANTÓNIO, 2011). A study conducted in South Africa at Baragwanth Hospital revealed that stroke constitutes about 60% of the neurological cases observed in that hospital (ANTÓNIO, 2011). Studies conducted in Zimbabwe and Nigeria have shown that the frequency of hemorrhagic stroke is high in relation to developed countries, a fact justified by the high prevalence of HTA in these countries (ANTÓNIO, 2011).

In Angola, the real magnitude of the socioeconomic impact of cerebrovascular diseases is not yet known due to lack of accurate data on epidemiological studies, but studies by students for end-of-course work have revealed a high frequency of stroke (more hemorrhagic than ischemic) in our hospitals. This is the case of kussola’s study on stroke morbidity and mortality in 62 patients admitted to the CSE (Sacred Hope Clinic) UCD (Diagnostic Center) in 2008 in which the lethality rate was very high reaching 50%, by António at HAB (Hospital Américo Boavida) in 2011 which revealed a lethality rate of 24% and by many others performed in 1999 , 2001, 2003 and 2004 which revealed that the frequency of stroke in our Hospitals in the Province of Luanda (ANTÓNIO, 2011) showed that the frequency of stroke was high in our Hospitals in the Province of Luanda (ANTÓNIO, 2011).

TYPES OF STROKE

Ischemic (vessel occlusion) and hemorrhagic (vessel rupture) stroke.

RISK FACTORS

Risk factors can be modifiable and non-modifiable. Among the modifiable individuals, hypertension (HTA), diabetes, smoking, heart diseases, dyslipidemia, obesity, sedentary lifestyle, alcoholism, and socioeconomic factors. Among the non-modifiable scans we find age, gender, race, family history (ANTÓNIO, 2011; FERREIRA et. al., 2013; CHAVES, 2013)

Table 3- Degree of dependence on the Barthel index

| Autonomous | 100 points |

| Mild dependent | > 60 points |

| Moderate Dependent | > 40 and ≤ 60 points |

| Severe ly dependent | ≥ 20 and ≤40 points |

| Total Dependent | < 20 points |

Source: Adapted from (RICARDO, 2012)

(score: 0-100 points)

GOALS

General:

- Evaluate the social and economic weight of stroke in patients and family members, followed by the external consultation of Neurology of the Hospital Américo Boavida and the Center for Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation from June to August 2013

Specific:

- Describe the socio-demographic profile of the study population.

- Characterize the sample according to the monthly income of the household.

- Evaluate the economic impact of the disease on the family as a function of the monthly income of the household.

- Describe the social implications of the disease on the family.

- To relate the degree of functional dependence measured by the Barthel Index and the socioeconomic impact.

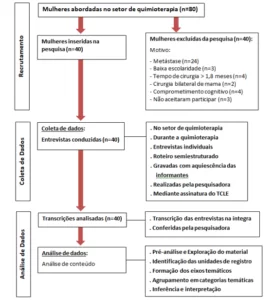

METHODOLOGY

STUDY SITE

The study was carried out at the external consultations of the Hospital Américo Boavida (H.A.B.) and in the gymnasium of the Center for Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (CMFR).

TYPE OF STUDY

An observational, descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted of all post-stroke patients assisted in the external neurology consultation of the Hospital Américo Boavida H.A.B. and at the Center for Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation C.M.F.R., from June to August 2013.

UNIVERSE

The study population consisted of all patients after stroke followed in an external consultation HAB and CMFR from June to August 2013.

SAMPLE

The sample was non-probabilistic, convenience-type consisting of 56 patients after stroke followed in an external consultation of H.A.B. and C.M.F.R., from June to August 2013.

INCLUSION CRITERIA

All patients were included in the study, followed by external consultations of the HAB and in the CMFR who were victims of confirmed stroke in the process with a period of up to 2 months at least, without verbal disability and willing to participate in the study, whose relatives also agreed.

EXCLUSION CRITERIA

All patients with confirmed associated pathology and those without companions (informal health care providers) were excluded.

VARIABLES

Socio-demographic identification (Age, Gender, marital status, Occupation, level of education and household), ways of going to consultations, degree of kinship with the informal provider, becoming unemployed due to illness, monthly income of the household, economic impact of stroke (forms of expenditure and total expenses) degree of functional dependence.

DATA COLLECTION AND PROCESSING

Data collection was made by applying a form that aimed to determine the socioeconomic and demographic characterization of the sample, as well as to record the barthel index assessment that aimed to determine the degree of functional dependence after the disease. The data were entered in an Excel database, processed and analyzed through descriptive statistics in the Software SPSS version 19.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) – Statistical Package for Social Sciences.

The results were written in text form, presented in tables and graphs through the Microsoft Word 2010 Program®, later designed through a projector in the Microsoft PowerPoint 2010 Program® in Windows 8® environment, on the day of public communication.

ETHICAL ASPECTS

The study was authorized by the FMUAN (Faculty of Medicine of the Agostinho Neto University) Board of Directors as well as the Clinical Directorates of HAB and CMFR, through a letter that was sent in advance, as well as informed consent made in a tacit manner, and there is a commitment to maintain anonymity and confidence in relation to patient data.

DEFFICULTIES

Having online the sociodemographic characteristics of the individuals who comprised the sample (including low education-education), most patients did not have a fixed income, did not know how to specify the monthly income of the household, or had a clear idea of the total expenditure, which required time, calculations and a lot of patience to estimate from data from basic questions.

OPERATIONAL SETTINGS

Monthly household income: The sum of all income of productive individuals that make up the family.

Minimum wage: The minimum that can be paid to an employee who in our country, according to the most recent publication (year 2012) in the daily of the Republic of Angola is 15,000 Kwanzas.

Informal care provider: Every individual who establishes some socio-affective-emotional relationship with the sick person and with responsibility to care for them, assisting in all daily activities, which he/she cannot perform alone taking into account the deficiencies, disabilities and disadvantages caused by the disease.

RESULTS

PRESENTATION OF RESULTS

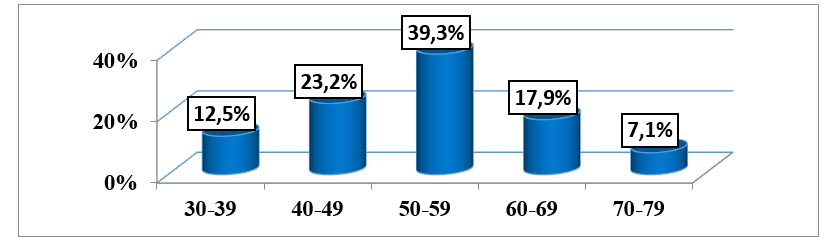

Of the 56 patients included in the study, we found that the mean age was 53.04 years (±10.44), ranging from 32 to 77 years, and the modal age group was 50-59 years representing 39.3% of the patients who make up the sample. (graph 1).

Graph #1: Distribution of the sample, according to age, followed by an external consultation of the HAB and CMFR from May to August 2013.

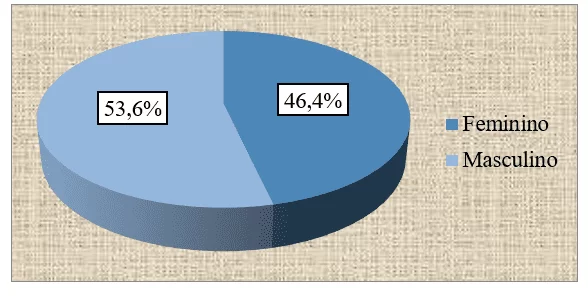

Of the total number of patients observed in both health institutions, we found that 26 (46.4%) were female, while 30 (53.6%) were male. (graph no. 2).

Graph 2: Distribution of the sample, according to gender, followed in an external consultation of the HAB and CMFR from May to August 2013.

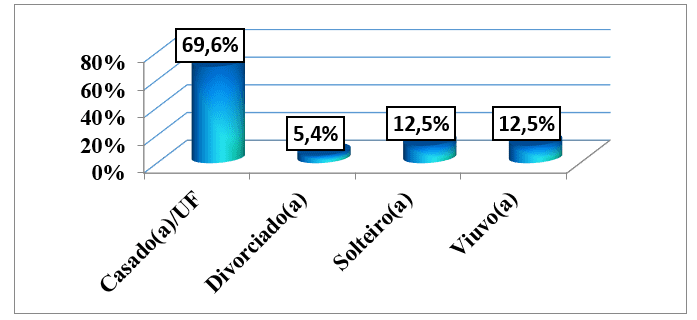

Regarding marital status, we saw that 39 (69.6%) patients were married and/or lived in a fact-union, following singles and widowers with 7 (12.5%) Sick. The minority, 3 (5.4%) was divorced. (graph 3).

Graph #3: Distribution of the sample, according to marital status, followed by an external consultation of the HAB and CMFR from May to August 2013.

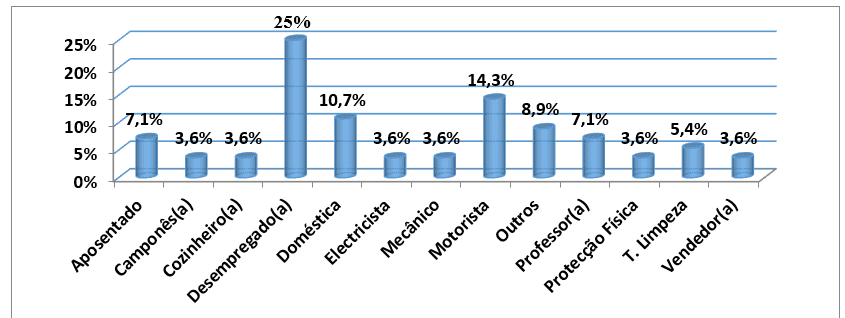

About professional occupation, it was observed that 14 (25%) of the 56 patients studied were unemployed, followed by those who were drivers with 8 (14.3%) patients and domestic servants who were 6 (10.7%) Sick. There were 4 (7.1%) retired patients and other less frequent occupations, with one case only for each, which in total were 5 (8.9%). (graph 4).

Graph #4: Distribution of the sample, according to occupation, followed by an external consultation of the HAB and CMFR from May to August 2013

Source: Author’s Data Collection Database

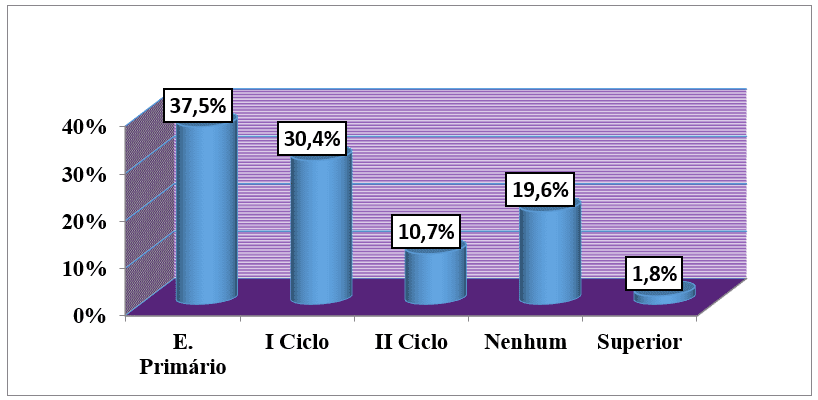

Regarding education level, 21 (37.5%) were from primary education while 17 (30.4%) were from the first cycle. Only 1 patient had higher education, which corresponds to 1.8% of all studied. (graph no5).

Graph 5: Distribution of the sample, according to the level of education, followed by an external consultation of the HAB and CMFR from May to August 2013.

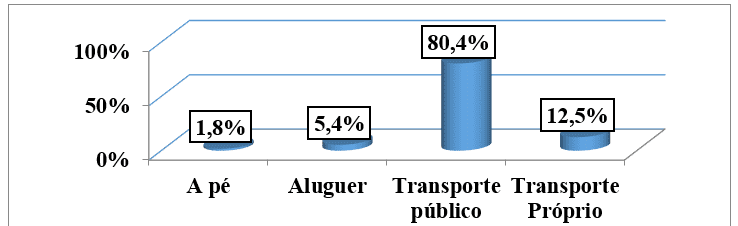

When evaluating the main ways of consulting patients included in the study, we found that 45 patients equivalent to 80.4% of the sample, go by taxi to consultations. Seven patients (12.5%) public transport and 3 patients (5.4%) rental transportation. There were only 1 patient (1.8%) who referred to going to the consultation on foot. (graph no6)

Graph no. 6: Distribution of the sample, according to the ways of going to consultations, followed by an external consultation of the HAB and CMFR from May to August 2013.

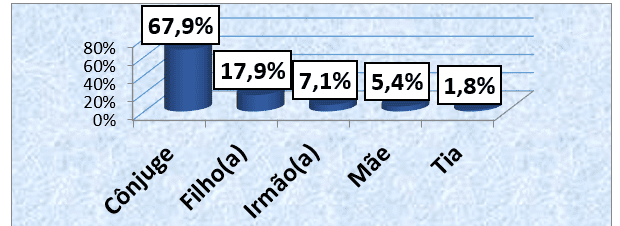

Regarding the degree of kinship of informal health care providers, we found that 38 (67.9%) were cared for by the conjunge, and 10 (17.9%) patients were cared for by their children. Only 1 (1.8%) patient reported being cared for by the aunt. (graphs 7).

Graph 7: Distribution of the sample, according to the degree of kinship with the informal health care provider, followed in an external consultation of the HAB and CMFR from May to August 2013.

Of the 14 patients who were unemployed, 100% reported being unemployed due to their illness. (graph no. 8).

Graph 8: Distribution of the sample, according to unemployment motivated by the disease, followed by an external consultation of the HAB and CMFR from May to August 2013.

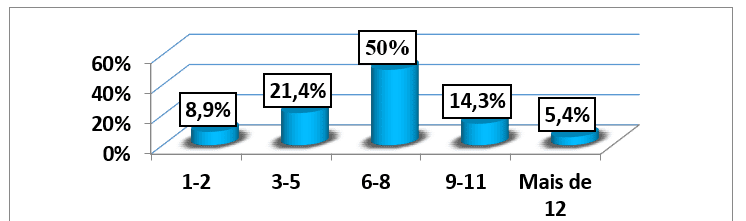

The average household of the 56 patients studied was 6.71 (±2.78) people, where the minimum household consisted of 1 person and the maximum per 15 people. The modal household was the range of 6-8 people (28 aggregates), corresponding to 50% of all households of the patients studied. (graph no. 9).

Graph no. 9: Distribution of the sample, according to the household number, followed by an external consultation of the HAB and CMFR from May to August 2013.

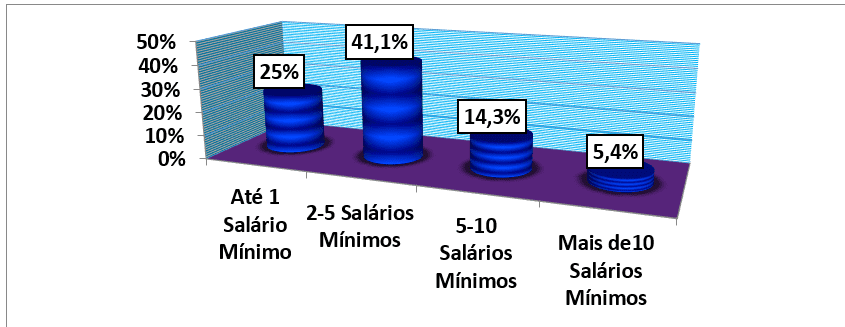

Analyzing the monthly income per number of minimum wages of the households of all patients included in the study, it was found that the average monthly income was 52139 kwanzas (±51 712 40) (4 Minimum wages) which is contained, at the same time, in the modal monthly income of 2-5 minimum wages corresponding to 41.1% of the study population. The minimum income studied was 7000 kwanzas equivalent to approximately half of a minimum wage, included in the 14 patients (25%) of households classified with income of up to 1 minimum wage and the maximum income was 260,000 Kwanzas (17 minimum wages) which was also included in the 3 patients (5.4%) households with more than 10 minimum wages. (table no. 1 and graph no10).

Graph 10: Distribution of the sample, according to the monthly income of the household in number of minimum wages, followed by an external consultation of the HAB and CMFR from May to August 2013.

Analyzing the main forms of expenditure by the disease, we found that more is spent by complementary diagnostic tests with an average of 9,844.64±15 840,798 ranging from 0 to 75,000.00. The consultations are the ones with the lowest monetary cost that carries an average of 633.93±1373,420 and the minimum value was 0 and the maximum value was 7 500.00. (table 1).

Table #1: Distribution of the average monthly income values, main forms of expenditure and total expenditure for the disease of the 56 patients followed in an external consultation of the HAB and CMFR from May to August 2013.

| Variables | Average | Median | Minimum | Maximum | Standard deviation |

| Income | 52139,00 | 39500,00 | 7000,00 | 260000,00 | 51712.449 |

| Queries | 625,00 | 500,00 | 0,00 | 7500,00 | 1375.929 |

| Exams | 9845,00 | 5900,00 | 0,00 | 75000,00 | 15840.798 |

| Medication | 6921,00 | 5250,00 | 0,00 | 35000,00 | 6451.264 |

| No. S. Rehabilitation | 5073,00 | 7200,00 | 0,00 | 45000,00 | 6349.617 |

| Transport | 6146,00 | 3500,00 | 0,00 | 48000,00 | 7797.155 |

| Total expenses | 28611,00 | 21100,00 | 6000,00 | 134700,00 | 25936.816 |

Source: Author’s Data Collection Database

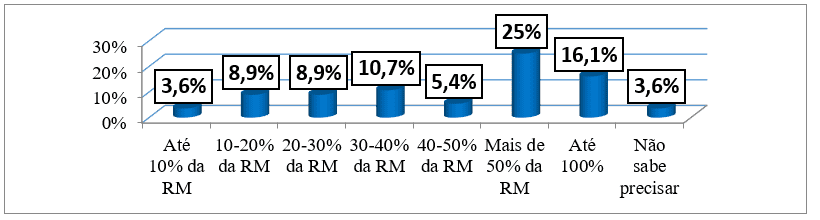

Regarding the monthly expenditure for the disease as a function of monthly income, it was found that patients spent in total 28510.71±28510.71, ranging from 6,000 Kwanzas (more than 80% of the minimum monthly income) to 134,500 Kwanzas (more than 50% of the maximum end of monthly income). 25% (14 patients) of the sample spent more than 50% of the monthly household income while 10 (17.9%) patients spent more than 100% of their monthly income and only 2 (3.6%) patients spent up to 10% of their monthly income on their illness. As we can see in table 1 and graph 11.

Graph no. 11: Distribution of the sample, according to the monthly expenditure for the disease, followed by an external consultation of the HAB and CMFR from May to August 2013.

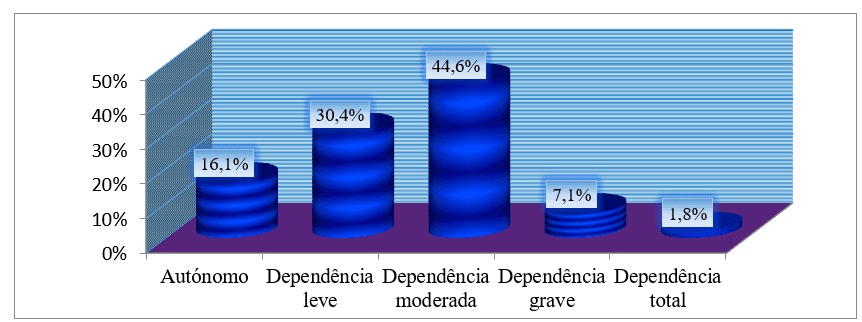

Taking the degree of functional dependence by the Barthel index, we saw that of the 56 patients, more than 70% had a certain degree of dependence, and the most frequent degree of dependence was moderate with 25 (44.6%) Sick. Only 9 patients were self-employed corresponding to 16.1% of the sample. (See graph 12).

Graph no. 12: Distribution of the sample, according to the degree of dependence by the Barthel index, followed in an external consultation of the HAB and CMFR from May to August 2013.

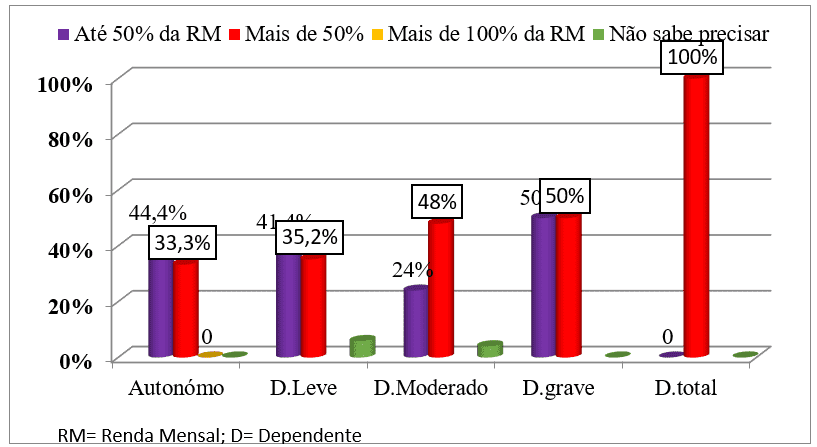

Relating the functional dependence measured by the IB and the total expenditures, we found that among the patients who were autonomous (44.4%) and mild dependents (41.4%) spent less than 50% of monthly income for the disease while patients with moderate dependence (48%), severe dependence (50%) and total dependence (100%) spent more than 50% of their monthly income for the disease. (see graph 16).

Graph no. 13: Distribution of the sample, according to the degree of dependence by the Barthel index and the total expenditures, followed by an external consultation of the HAB and CMFR from May to August 2013.

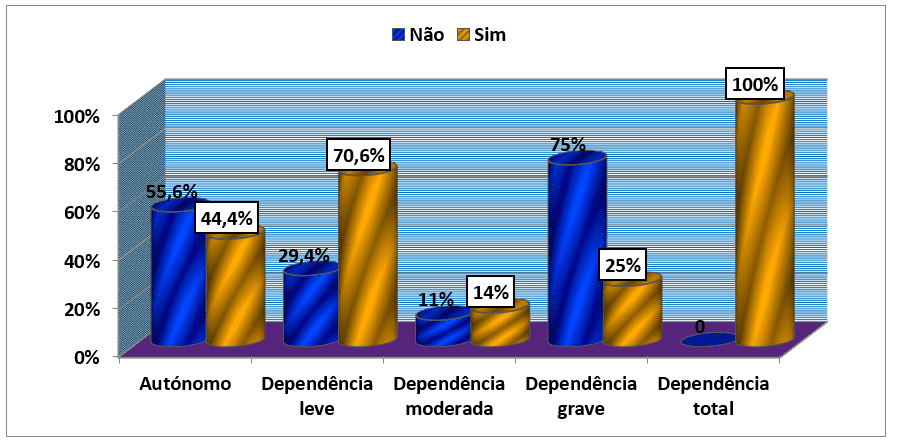

Analyzing the question of whether or not to become unemployed and the degree of dependence on the barthel index, we found that of the patients who were self-employed 5 (55.6%) patients responded negatively while the minority (44.4%) answered affirmatively. The reverse happened among patients with some degree of dependence in which the majority, with very few exceptions, responded affirmatively and the minority negatively. In this way, it should be noted that of the 12 patients with mild dependence 70.6% answered yes to the question and 29.4% answered no; Among patients with moderate dependence 14% answered yes against 11% who answered no. (graph 16).

Graph #14: Distribution of the sample, according to the question of whether or not to become unemployed due to disease and the degree of dependence by the Barthel index, followed by an external consultation of the HAB and CMFR from May to August 2013.

DISCUSSION OF RESULTS

The mean age was 53.04 years (±10.44), ranging from 32 to 77 years, with predominance of the 50-59 age group. These results are similar to those found by Falcão et. Al. (2004) in a study on implications of early stroke for adults of productive age attended by the single health system, in which there was a higher concentration of patients in older age groups with a fashion equal to that of the present study of 50-59, which represented 56.5% of its sample, and the mean age was 52 years (FALCÃO et. al., 2004). Kussola (2008) in a study on stroke morbidity and mortality in the Differentiated Care Unit of the CSE, observed a higher prevalence between the fourth and fifth decade of life. António (2011) in his study on stroke morbidity and mortality in patients admitted to the Neurology Service of hospital Américo Boavida, found a predominance of the 60-69 year old age group (ANTÓNIO, 2011). These results include bibliographic support according to which, the frequency with which a stroke occurs increases exponentially with age, above 50 – 60 years or from them and the “risk of stroke is directly proportional to age” (RICARDO, 2012). Different from the results of the present study are those found by Ricardo (2012) in a study on Evaluation of health gains using the Barthel Index, in patients with acute stroke and after discharge, with rehabilitation nursing intervention, in which the mean age was 75 (±10.1) years, with predominance of the 70-79 years age group (RICARDO , 2012).. This difference is understandable by the life expectancy that is relatively low in our country.

The male predominance with 30 (53.6%) compared to females with 26 (46.4%) coincides with the study by Ricardo (2012) on Evaluation of health gains using the Barthel Index, in patients with acute stroke and after discharge, with rehabilitation nursing intervention (54.8% male and 43.2% female) (RICARDO, 2012)., by Silva and Costa (2012) in a study on the profile of the patient with stroke and possible differences and similarities between the sexes (51.6% male and 48.4% female) , by Valverde (2007) in his study on the profile of stroke patients treated at the emergency hospital in Goiânia (58.6% male and 41.4% female) and many other studies involving stroke patients such as Kussola (2008), Massango (2009), Falcão et. Al. (2004), by Duncan et. Al. (2003), by Saposnik; Del Brutto (2003), de Medina; Shirassu; Goldefer (1998); Rodrigues; Sá; Alouche (2004); Nunes; Pereira; Silva (2005); Radanovic (2000); pires; Gagliardi; Gorzoni (2004); Melcon (2006); of Anesi; Okubadejo and Ojini (2007); (RIBEIRO et. al., 2012). These results confirm the consensus in the literature that “in men the incidence of stroke is slightly higher” (RICARDO, 2012). As a rule, women of childbearing age are less predisposed to stroke due to hormonal protection. After 50 years of age, the incidence of this pathology is the same in both sexes, occurring more in males (RICARDO, 2012). The studies done by Ribeiro et. Al. (2010) on the characterization of users with stroke and social responses after discharge and Por António (HAB/2011) on Determinants of Stroke Morbidity and Mortality in patients admitted to the Neurology Service of the HAB, contrast with the present study, however, there was a predominance of females over males, which may be understandable, since, although morbidity is more frequent in males, mortality from stroke is higher in females, probably due to the fact that stroke in women occurs at older ages (RICARDO, 2012).

Regarding marital status (69.6% married and or lived in a union of facts, 5.4% divorced/to 12.5% single and widowed), it coincides with the results found by Falcão et. Al. (2004) in a study on implications of early stroke for adults of productive age attended by the unified health system, in which married marital status or union of facts prevailed before and after stroke, by Alves et. Al. (2010) in a study on depression after stroke: Nursing intervention (62.5% married), by da Costa (2010) in his study on Cognitive and functional evolution of post-stroke patients (more than 50% were married) and by Pereira et. Al. (2009) in its study on the prevalence of stroke in the elderly in the municipality of Vassouras, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, through the tracking of data from the Family Health Program (SILVA and COSTA, 2012; COSTA, 2003). The broad convergence of the data described above has bibliographic support, because stroke occurs at advanced ages at a time when most people have already contracted their marriage and/or cohabitin union of facts and the degree of partnership is so intense at this stage, that does not allow easy divorces even in the face of a strongly disabling disease such as stroke, which is why married marital status/or fact-finding is predominant in all research papers (which includes stroke patients) consulted, described and not described in the present study.

It was observed that 14 (25%) of the 56 patients studied were unemployed, followed by those who were drivers with 8 (14.3%) patients and domestic servants who were 6 (10.7%) Sick. There were 4 (7.1%) retired patients and other less frequent occupations, with one case only for each, which in total were 5 (8.9%). It should be noted that in this study 80.4% of patients reported going to public transport consultations (see graph 5 and table attached). These results are similar to those found by Falcão et. Al. (2004) in a study on implications of early stroke for adults of productive age attended by the single health system, in which it was observed that stroke brought changes, reducing the condition of workers. Before stroke, 83% of men and 54% of women were working; after stroke, only 25% of men and 4.5% of women maintained this condition” (RICARDO, 2012). The predominance of unemployed after illness may be justified by the deficiencies and disability caused by stroke, the relatively high percentage of retirees may be a reflection of the advanced age of patients while the highest reference of activities of low professional qualification (with less intellectual involvement) and the predominance of patients who take public transport consultations (due to lack of own transport) , may reflect a low socioeconomic level of individuals since historically, professional occupation has been considered as the most reliable indicator of the relative position of any individual in the social hierarchy (RICARDO, 2012). It provides socioeconomic information because it serves as the basis for a salary scale; different levels of security and financial stability in different professions; different authority and control to each professional occupation (offering different levels of personal satisfaction and physical and psychological tension); and of different degrees of prestige be attributed to different occupations (RICARDO, 2012). Occupational status is also indicative of concomitant health risk factors in certain professions, such as exposure to toxic agents or risks to physical integrity (RICARDO, 2012). Together with two indicators that will lower below we will focus on (level of education and monthly income) allow social stratification in class. And considering that the type of pathology varies with the social class, it is stated that stroke affects mostly the most disadvantaged classes as the present work presents. And from the point of view of socioeconomic impact, it greatly increases family expenses and considerably decreases the quality of life of both the individual and his family, thus installing a vicious cycle of positive feedback.

Of the 56 patients who comprised the sample, 21 (37.5%) were from primary education while 17 (30.4%) were from the first cycle. Only 1 patient had higher education, which corresponds to 1.8% of all studied. These results are due to the fact already clarified in the previous discussion in which the level of education is the prerequisite for professional occupation and consequently income, and the three indicators together inform the socioeconomic level of the individual. It is known that the level of education of a population is related to the state of health. More specifically, there is a significant correlation between the education of parents and the health of their children. This indicator can provide more information in the event of discrimination according to educational levels. Individuals with a better educational level have a higher occupational situation, better housing conditions and healthier lifestyles (RICARDO, 2012). Therefore, being of a low socioeconomic level is a major risk factor for cerebrovascular diseases such as stroke. For this reason, there is great agreement of the present study with those conducted by de Santana (1996) on socioeconomic characteristics of stroke patients in which 82% were illiterate and or semi-illiterate, by Fernandes and Santos (2009) on motor and functional evolution of stroke patients in the first three months of life after hospital discharge in which 50% were from the I cycle followed by those who were illiterate with 36.7% , by Pereira de Sá (2013) on the influence of sociocultural parameters on the recognition of stroke in which 63.4% were from primary education followed by illiterate patients with 25.7%, by Albuquerque and Coelho (2010) on determinants of functional capacity of patients after stroke in which the most representative group was basic education (I cycle) with 55.8%. The least representative group was from higher education, only with 4.9%, by Panhoca and Gonçalves (2009) on Aphasia and quality of life consequences of a stroke from the perspective of speech therapy in which it was observed that the population studied has low schooling, and 12.5% are illiterate and 45% attended elementary school (SÁ, 2009; PANHOCA and GONÇALVES, 2009; SANTANA et. al., 1996) and many other studies conducted in different parts of the world.

Regarding the degree of kinship of the informal provider, it was found that 38 (67.9%) were cared for by the conjunge, and 10 (17.9%) patients were cared for by their children. Only 1 (1.8%) patient reported being cared for by the aunt. This fact is very much related to the definition of informal provider given by Edivaldo according to which an informal provider is everyone who provides care and assistance to others, but without remuneration. Generally, this service is provided in a relationship context already in progress. It is an expression of love and affection for a family member, friend or simply for another human being in need. Caregivers, in the informal system, assist the person who is partly or totally dependent on assistance in their daily lives, such as: to dress, food, hygiene care, transportation dependence, medication administration, food preparation and finance management (BAIA, 2010). And, generally, in a home, the person with the aforementioned qualifications has been the spouse, which justifies the results found in the present study. On the other hand, when we found a greater reference of the spouse as an informal provider, our study is coincident with the study by Baia (2010) on stroke patients: family difficulties in which 60% of the respondents stated that the informal caregiver is the husband/wife for 32% of the respondents, the informal caregiver was the child (BAIA, 2010). Gomes (2010) in his study on Satisfaction regarding educational and socio-health services available to stroke patients. The perspective of the informal caregiver found that the degree of husband/wife kinship represented 58.7%, the Son represented 26.1% as Brother/to 6.5% (GOMES, 2010). Costa (2003) in his study on post-stroke quality of life found that the highest percentage of providers were husband/wife and children (COSTA, 2003).

Most patients (69.6%) was unemployed and/or stopped studying due to her illness, clearly reflecting the great negative impact of stroke from a socioeconomic point of view. We believe that this result is due to the fact that this pathology is a strong cause of disability, disability and disadvantage. According to the bibliography, professional status changes with stroke, moving from worker to retired (RICARDO, 2012) ; which coincides with the results of Falcão et. Al. (2004) in a study on the implications of early stroke for adults of productive age treated by the single health system, found that stroke brought changes, reducing the condition of workers. Before stroke, 83% of men and 54% of women were working; after stroke, only 25% of men and 4.5% of women maintained this condition (FALCÃO et. al., 2004). However, they report that in a population of 15 to 45 years the return to work of just over 70%, on average, after eight months of stroke, although there was a need for adjustments in the occupation of, about 26%. Ching-Lin and Mong-Hong found 60% return to work, with a complete return of almost half of these and limitation in the work day or type of work of the rest (RICARDO, 2012). The difference of these results with ours is understood by the time of disease evolution in the study population in which for our case it was relatively smaller.

In this study we found that most patients had a household of 6-8 people with a monthly modal income of 2-5 minimum wages, and the minimum wage was 7000 kw and the maximum was 260000 Kw with an average of 52139 kwanzas. This result, in the same sense as has been discussed so far on the influence that the socioeconomic level has on susceptibility to the pathology in question, is a consequence of the cascade, with some vicious cyclical degree, in which the low socioeconomic level conditions low educational level with consequent unprofitable occupations. And while this happens the number of children tends to be greater also extending the household. Santana et. Al. (1996) when studying the socioeconomic characteristics of stroke patients, it found that 82% of patients were illiterate or semi-illiterate, more than half of their sample had an aggregate of 2-4 people and 60% lived with a family income of 1 to 2 minimum wages (SANTANA et. al., 1996). The differences found in this study regarding the household, we think, are due to cultural issues, in our environment, in which the more one is of the poor layer, the more fulfilled with the vision of having children as a kind of long-term investment for sustenance in old age and, paradoxically, end up being more an overload than a help, due to the inability that parents have , given its limitations, to grant sufficient education and education for the change in socioeconomic status to take place. God (2013) in his study on death by stroke is higher in the urban area of the city of Amazonas, found that the most common profile of those affected by the disease was men, brown, without formal study and with income of one to two minimum wages (DEUS, 2013). Ribeiro et. Al. (2012) when studying the Profile of Users Affected by Stroke Assigned to the Family Health Strategy in a Capital of northeastern Brazil, inferred that the socioeconomic situation also plays a determining role in the health of individuals, observing that the majority of respondents had family income between 1 and 2 minimum wages (49.3%) for the maintenance of the whole family (RIBEIRO et. al., 2012). Dias (2006), in its cross-sectional research, with 82 users, in 12 Family Health Units in the city of Divinópolis- MG, found a prevalence of 622 reais as an average of family income (RIBEIRO et. al., 2012). So the convergence, with the literature, of the results of the present study, in relation to this indicator, is quite intense.

25% (14 patients) of the sample spent more than 50% of the monthly household income while 10 (17.9%) patients spend more than 100% of their monthly income and only 2 (3.6%) patients spend up to 10% of their monthly income on their disease. This result gives a clear notion of the great socioeconomic impact of stroke on the family taking into account the other basic needs that lack financial coverage. On the other hand, it goes against the bibliography that says that the cost of stroke is quite large for the family and society in general, either by increasing spending or by reducing the production capacity of the subject (in Brazil 40% of all early retirements are due to this disease) (RIBEIRO, 2011). Of the research, almost no study focused on monthly expenses by a stroke patient, but a study by Ribeiro (2011) on stroke weight and Atrial Fibrillation inferred that the costs are quite high for the state. Up to R$12,000 is spent by the Unified Health System for each victim of fatal ischemic stroke. In 2009, The SUS spent R$150 million on hospitalizations alone (RIBEIRO, 2011). Pieri reveals that stroke leads to enormous costs with hospitalization, rehospitalizations, retirement, sickness benefits and rehabilitation (RIBEIRO, 2011).

Taking the degree of functional dependence by the Barthel index, we saw that of the 56 patients, more than 70% had a certain degree of dependence, and the most frequent degree of dependence was moderate with 25 (44.6%) Sick. Only 9 patients were self-employed corresponding to 16.1% of the sample. This result is very much related to the fact that stroke is the main cause of disability and functional disability. In the study carried out by Matos et. al., (2003), published in the Journal of the Faculty of Medicine of Lisbon, with the objective of assessing the degree of dependence in patients who have suffered stroke, in a list of users of a family doctor, revealed that 19.2% of users are independent; 57.7% have a mild to moderate dependence; 11.6% have severe dependence and 11.5% are totally dependent. The overall score presented a minimum value of 0 (totally dependent) and a maximum value of 20 (independent), and the median was observed in 90 (mild to moderate dependence). Studies by the General Directorate of Health, published in the recommendations of stroke units in 2001/Portugal, reveal that three months after stroke, 24% of patients are severely dependent, 18% are mildly dependent and 30% are independent. The existing convergence with the present study supports the existing consensus in the literature that currently, the IB continues to be widely used, mainly in the hospital context, convalescence units and rehabilitation centers and several authors consider it the most appropriate instrument to evaluate the inability to perform activities of daily living. And that the differences that may exist between the percentages of mild, moderate and severe can be understood as the time of occurrence of the disease in which patients tend to be more dependent at the beginning and with the passage of time taking into account rehabilitation begin to resume functions from low scores (very dependent) to high (autonomy).

Relating the functional dependence measured by the IB and the total expenditures, we found that among the patients who were autonomous (44.4%) and mild dependents (41.4%) spent less than 50% of monthly income for the disease while patients with moderate dependence (48%), severe dependence (50%) and total dependence (100%) spent more than 50% of their monthly income for the disease. These results are due to the fact that autonomy is a clear sign of healing and complete recovery of the nosological entity and its sequelae, an indicator of the reduction of activities that are reasons for expenditure of money and the increase in the production capacity of the individual. The patient with autonomy goes alone to the hospital (which implies little expense with transportation), decreases or ceases with rehabilitation assignments, the number of tests to be requested, the expense of medications and others.

Looking at the question of whether or not to become unemployed and the degree of dependence on the Barthel Index, we found that of the patients who were autonomous 5 (55.6%) patients responded negatively while the minority (44.4%) answered affirmatively. The reverse happened among patients with some degree of dependence in which the majority, with very few exceptions, responded affirmatively and the minority negatively. This result is that the deficiencies and disabilities that stroke people impose lead people to stop performing their work activities. Falcão et. Al. (2004) in his study on early stroke: implications for working-age adults assisted by the Unified Health System in which he inferred that after the stroke the number of unemployed and retired people increased and disabilities negatively affect the life satisfaction of more than 70% of the interviewees (RIBEIRO, 2011).

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

- In the sample studied, there was a predominance of individuals in the fifth decade of life, and males were more frequent. They were mostly married, with no professional occupation, with primary education predominant.

- Most patients had a monthly income of 2-5 minimum wages which on average were estimated at 52139 kwanzas with a modal household of 6-8 people per family.

- Most patients had some degree of dependence and almost all of them became unemployed due to their illness and reported an increase in monthly spending consuming more than 50% of the monthly income due to the disease alone.

- Predominantly the patients were cared for, at home, by the spouse or child, which clearly shows the social implications that the disease causes in the family.

- Finally, it was found that the higher the functional dependence, the higher the monthly expenditure for the disease and the higher the degree of unemployment.

- The competent governmental and non-governmental institutions that encompass a philanthropic nature, in order to create policies to educate the population, especially the most deprived, in relation to the risk factors of stroke on the one hand and the subsidy of the expenses of stroke patients on the other hand, taking into account the lack of both educational-instructive and economic.

- Institutions aimed at the rehabilitation of patients (especially the Center for Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation), which apply a monetary discount depending not only on age as it is currently done, but also on severity.

- Doctors dealing with stroke patients, in order to appeal to family members not to allow people of school age or in the performance of their professional and economically productive functions to be held accountable for the care of

- To the student community, so that studies of socioeconomic impact of stroke continue to be done, in order to attract the attention of the competent entities for an effective intervention both preventive and therapeutic.

REFERENCES

ABE, I. L. M. Prevalência de acidente vascular cerebral em área de exclusão social na cidade de São Paulo, Brasil: Utilizando questionário validado para sintomas. Tese apresentada à Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo para obtenção do título de Doutor em ciências. 2010, disponível em http://www.google.com/#sclient=psy- Acesso em 28/06/2013, pelas 18:38.

AHLISIO B., et. al. Disablement and quality of life after stroke. Stroke 1984; 15: 886-890.

ANTÓNIO, J. M., JAMBA, Determinante de Morbimortalidade por AVC em doentes admitidos no Serviço de Neurologia do Hospital Américo Boavida de 1 de Outubro de 2010 a 31 de Maio de 2011 (Monografia). Luanda Faculdade de Medicina 2011.

ARAÚJO, F., et. al. Validação do Índice de Barthel numa amostra de idosos não institucionalizados. Qualidade de Vida. (2007).vol. 25, nº 2, p. 59-66.

ASTROM M., ASPLUND K., ASTROM T. Psychosocial function and Life Satisfaction After Stroke. Stroke 1992; 23:527-531.

BAIA, P. R. P. Doente com AVC: Dificuldades da família. Faculda Ciências da Saúde/Universidade Fernado Pessoa do porto.2010. Disponível em http://www.google.com/url. Acedido aos 14/10/2013 pelas 16:40.

BARBOSA V. Acidentes Vasculares Cerebrais no Idoso. Geriatria 1992; 5; 50: 24-29.

BETH HAN, W. E. H. Family Caregiving for Patients With Stroke – Review ad Analyses. Stroke 1999; 30:1478-1485.

BOBATH, B. (1990). Hemiplegia no Adulto: Avaliação e Tratamento. São Paulo: Editora Manole. 182 pp.

BONITA R. Epidemiology of Stroke. Lancet 1992; 339:342-347.

BONITA R. Prevalence of Stroke and Stroke-Related Disability Estimates from the Auckland Stroke Studies. Stroke 1997; 28:1898-1902.

BONITA R, STEWARD A, BEAGLEHOLE R. International trends in stroke mortality: 1970-1985. Stroke 1990; 21:989-992.

BRITTAIN K., PEET S. Stroke and Incontinence. Stroke 1998; 29: 524-528.

BRITTA LOFGREN, YNGVE GUSTAFSON. Psychological Well-Being 3 Years After Severe Stroke. Stroke 1999; 30:567-572.

CABRAL, N. et al. Epidemiologia dos Acidentes Cerebrovasculares em Joinville, Brasil. Disponível: http://www.google.com/#sclient=psy. Acedido aos 03/07/2013, pela 16:14.

CAROD-ARTAL, E. N. et. al. Percepción de la sobrecarga a largo plazo en cuidadores de supervivientes de un ictus. Rev Neural 1999; 28(12): 1130-1138.

CENSORI B. Dementia after first stroke. Stroke 1996; 27(7): 1205-1210.

CESÁRIO, C. M. M. et al. Impacto da disfunção motora na qualidade de vida em pacientes com Acidente Vascular Encefálico. Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Departamento de Neurologia e Neurocirurgia, escola Paulista de Medicina. 2009. Disponível em http://www.unifesp.br/dneuro/neurociências/neuro_vol_14_nl_07_06_06_LAYOUT_08.pdf. Acedido em Maio de2013 pelas 13H:34.

CHAGAS, N. R. E MONTEIRO, A. R. M. Educação em saúde e família: Cuidado ao paciente vítima de Acidente Vascular Cerebral. Disponível em: http://www.google.com/#sclient=psy-ab&q. Acedido aos 04/07/2013, pelas 19:39.

CHAVES, M. C. F. Acidente Vascular encefálico: Conceituação e factores de risco. 2000. Disponível em: http://www.google.com/#sclient=psy-ab&q. Acedido aos 05/072013 pelas 23:00.

CHARLES A. Variations in Case Fatality and Dependence From Stroke in Western Central Europe. Stroke 1999;30:350-356.

CORREIA, A. L. F. Factores genéticos de risco para Acidente Vascular Cerebral jovem. (dissertação de mestrado). Universidade de Aveiro: Departamento de biologia, 2011.

CORREIA, M. Acidentes vasculares cerebrais e sintomas e sinais neurológicos focais transitórios – Registo prospectivo na comunidade. Repositório do Centro Científico do Centro Hospitalar do Porto, Portugal 2006. Disponível em: http://hdl.handle.net/10400.16/1374. Acedido em Maio de 2013 pelas 15H: 03.

COSTA, D. C. A. Qualidade de vida pós AVC: Resultados de uma intervenção social. (Dissertação). Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto. Julho de 2003.

DEUS, L. Morte por AVC é maior na zona Urbana de cidade do Amazona. Agência do USP de notícias, S. Paulo/2013. Disponível em http://www.usp.br/agen/?p=150282. Acedido aos 17/10/2013 pelas 8:31.

EKER T. Harv. Secrets of the millionaire mind. 2ª edição. E.U.A. – SEXTANTE

FALCÃO et al. Acidente vascular cerebral precoce: implicações para adultos em idade produtiva atendidos pelo Sistema Único de Saúde. (2004/Brasil). Disponível em http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid. Acedido aos 22/10/2013 pelas 21:18.

FERREIRA, C. et al. Factores de risco para Acidente Vascular Cerebral, versão final. 2006. Disponível em: http://www.google.com/#sclient=psy-ab&q. Acedido aos 05/07/2013 pelas 21:40.

FERRO, JOSÉ et. al. Recomendações para o Tratamento do AVC Isquémico. Lisboa. in The European Stroke Organization (ESO) Executive Committee and the ESO Writing Committee. (2008). 1-125.

FONTES N. A doença vascular cerebral estabelecida – recuperação motora. Geriatria 1998. 11; 104:5-10.

FONTES, N. (1998). A doença vascular cerebral estabelecida – recuperação motora. Geriatria, (1998) vol. XI, nº 104. p. 5-10.

GOMES, D. M. Acidente vascular cerebral-Principais consequências e reabilitação (Monografia). Porto Universidade Lusíada; 2008. Disponível em: http://www.psicologia.pt/artigos/textos/TL0095.pdf . Acedido em Maio de 2013 pelas 8:57.

GOMES, M. J. Satisfação relativa aos serviços educativos e sócio sanitários disponíveis para os doentes vítimas de AVC. A perspectiva do cuidador informal. Instituto Politécnico de Bragança/Escola Superior de Saúde. (2010). Disponível em http://www.google.com/url. Acedido aos 14/10/2013 pelas 17:50.

HARRISON et al. Tratado de Medicina Interna. 17ª edição; Rio de Janeiro:McGraw-Hill interamericana do Brasil, 2008. Pag. 2513-2518.

HÉNON H. Confusional state in stroke. Relation to Preexisting Dementia, Patient Characteristics and outcome. Stroke 1999; 30:773-779.

HISTORY OF STROKE. Disponível em http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/healthlibrary/conditions/nervous_system_disorders/history_of_stroke. Acedido aos 14/11/2012 pelas 18:40. Acedido aos 22/10/2013 pelas 22:18.

JONG S. KIM, SMI CHOI-KWON. Poststroke depression and emotional incontinence. Neurology 2000; 54:1805-1810.

JORGENSEN H., et. al. Factors delaying hospital admission in acute stroke: The Copenhagen Study. Neurology 1996; 47: 383-387.

KARSCH U. Envelhecimento com dependência: Revelando cuidadores. Livraria Educação – São Paulo, 1998; 10-246.

KAUHANEN M. et al. Poststroke depression correlates with cognitive impairments neurological deficits. Stroke 1999; 30:1875-1880.

LEAL, F. Enfermagem em Neurologia – Intervenções de Enfermagem no Acidente Vascular Cerebral. Lisboa: Edição Sinais Vitais. (2001). 220 pp.

LEGG L, et. al (2004). Reabilitation therapy services for stroke patients living at home: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. pp. 352–356.

LOGEN, W.C. Ginástica laboral na prevenção de LER/DORT – um estudo reflexivo em uma linha de produção (Dissertação), Florianópolis: Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina; 2003

M. Understanding Family Care. Open university Press-Buckingham, 1996; 2-193.

MATOS, Z., et. al. Grau de dependência em doentes com AVC. Lisboa: Revista da Faculdade de Medicina de Lisboa. Série III, Julho / Agosto. (2003) pp. 199-204.

MAHONEY, F. e BARTHEL, D. Functional Evolution. Ed. Med. J. (1965). 61-65.

MAYO NE, WOOD-DAUPHINE S, et al. Disablement following stroke: Disabil Rehabil 1999;(5-6): 258-268.

MBALA, C. Qualidade de vida dos estudantes da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade Agostinho Neto. (Monografia). Faculdade de Medicina/UAN. 2010.

MINISTÉRIO DO EMPREGO E DA SEGURANÇA SOCIAL. Classificação Internacional das Deficiências, Incapacidades e Desvantagens (Handicaps). Lisboa. 1989; 29-41.

NICOLETTI, A., et al. Prevalence of stroke: a door-to-door survey in rural Bolívia. Stroke 2000; 31:882-

NATIONAL STROKE ASSOCIATION. The Stroke-Ahead: A Stroke Recovery Guide. 1988.

O’ SULLIVAN, SUSAN. Avaliação e Tratamento. São Paulo: Editora Manole. (1993). 1200.

PADILHA, A. R. S. Ministério da Saúde. Implantando a linha de cuidado do AVC na rede de atenção das urgências, 2011. Disponível em: http://www.google.com/#sclient=psy. Acedido aos 03/07/2013 pelas 16h:00.

PAIXÃO, J. C. Uma revisão sobre instrumentos de avaliação do estado funcional do idoso. Republic Health: Caderno de Saúde Pública. (2005). p.7-19.

PANHOCA, I.; GONÇALVES, C. A. B. (2009) Afasia e qualidade de vida – consequências de um acidente vascular cerebral na perspectiva da fonoaudiologia. Arq. Ciênc. Saúde UNIPAR, Umuarama, v. 13, n. 2, p. 147-153 disponível em http://www.google.com/url? Acedido aos 14/10/2013 pelas 16:40.

PAUL M. Lá Para o Fim da Vida – Idosos, Família e Meio Ambiente. Livraria Almedina – Coimbra, 1997;9-171.

PEREIRA UP, A. F.AS. Neurogeriatria. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Revinter; 2001. 4.

PETER R. A Long-term Follow-up of Stroke Patients. Stroke 1997; 28: 507- 512.

PHIPPS, WILMA J. et. al. Enfermagem Médico-Cirurgica: conceitos e prática clinica. 6ª edição. Loures: Editora Lusociência. (2003).. pp.655-1339.

PIRES, S. L., et al. Estudo sobre frequência sobre os principais factores de risco para acidente vascular cerebral isquémico em idosos. Arq. De Neuropsquiatria, 2004 (3-B). pag 1-8.

P. LANGHOME, et. al. Medical complications After Stroke a Multicenter Study. Stroke 2000; 31:1223-1229.

RIBEIRO et. al. Perfil de Usuários Acometidos por Acidente Vascular Cerebral Adscritos à Estratégia Saúde da Família em uma Capital do Nordeste do Brasil. Brasil/2012. Disponível em http://www.google.com/url?. Acedido aos 17/10/2013 pelas 12:47.

RIBEIRO, J. L. PAIS (1998). Psicologia e Saúde. Lisboa: ISPA.

RIBEIRO. Peso do AVC e da Fibrilhação atrial. Brasil/2011. Disponível em http://tribunadonorte.com.br//o-peso-do-avc-e-da-fibrilacao-atrial. Acedido aos 21/10/2013 pelas 11:41.

RICARDO, R. M. P. Avaliação dos ganhos em saúde utilizando o índice de Barthel nos doentes com AVC em fase aguda e após alta com intervenção de enfermagem de reabilitação. (Dissertação). Instituto Politécnico de Bragança: Escola Superior de Saúde, Julho de 2012.

RODGERS H. Risk factors for first-ever stroke in older people in the North East of England: a population- based study. Stroke 2004; 35:7-11. 3.

SÁ, Maria José- AVC- Primeira causa de Morte em Portugal. Revista de Ciências de Saúde. Porto. Edições Fernando Pessoa. ISSN 1646-0480 2009 disponível em: http://bdigital.ufp.pt/bitstream/10284/1258/2/12-19_FCS_06_-2.pdf http://b. Acedido em Maio de 2013 pelas 16H:04.

SANTANA et al. Características socioeconômicas de pacientes com acidente vascular cerebral. Brasil/1996. Disponível em http://www.google.com/url. Acedido aos 17/10/2013 pelas 09:29.

SANTOS, V. Qualidade de vida após Acidente Vascular Cerebral, CHBA disponível em: http://www.google.com. Acedido aos 23/07/2013 pelas 16:30.

SILVA E COSTA. AVC e género-Perfil do doente com AVC e eventuais diferenças e semelhanças entre os sexos.2012. Disponível em: http://www.google.com/#sclient=psy. Acedido aos 03/07/2013, pelas 20:41.

STRATEN A, HAAN R. A Stroke Adapted 30 Item Version of the Sickness Impact Profile to Assess Quality of Life. Stroke 1997; 28: 2155-2161.

TOSELAND R., ROSSITER C. M. Social Work Practice with family caregivers of frail older persons in Social Work Practice in Health Care Settings. Canadian Scholars Press. 1994; 524-549.

VAN DES BOS GAM. The burden of chronic diseases in terms of disability, use of health care and health life expectancies. Eur J. Publ. Hlth 1995; 5:29-34.

VARTIAINEN E, et. al. Changes in risk factors explain changes in mortality from ischaemic heart disease in Finland. BMJ 309: 23-7, 1994.

VIITANNEN M, FULG-MEYER KS et al. Life satisfaction in long term survivors after stroke. Scand J Rehabil Med 1988, 20:17-24.

WEEN J., et. al. Factors predictive of stroke outcome in a rehabilitation setting. Neurology 1996;47: 388-392.

WILKINSON PR, et. al. A long-term follow-up of stroke patients. Stroke 1997;28(3):507-512.

WSO, Academia de Jornalismo da Organização mundial de AVC. 2012. Disponível em http://www.google.com/#sclient=psy. Acedido aos 03/07/2013, pelas 18:31.

[1] Doctor, Neurologist, Master’s student, Faculty of Medicine, University of Campinas.

[2] Advisor. MD, Neurologist, Phd.

Submitted: September, 2020.

Approved: October, 2020.