DISSERTATION

BARROZO, David da Costa [1], MAGALHÃES, Diego Ventura [2], FERREIRA NETO, Luiz Reis [3], FERREIRA, Marilia Matos Gonçalves [4]

BARROZO, David da Costa. Et.al. Solidarity economy and public management of solid waste in selective collection in Belém: analysis of the experiences of CONCAVES and COOTPA. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 03, Ed. 05, Vol. 03, p. 35-71, May 2018. ISSN:2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/business-administration/solidarity-economy

ABSTRACT

The context in which the Solidarity Economy has been highlighted in recent years. As for the precariousness of work, it is due to the very implication of salaried work in the conditions of the new flexible accumulation regime, which can be characterized by the transformation of the world of work, namely, by the systemic development of a complex process of productive restructuring and organizational changes. , by the emergence of a new and precarious world of work, and by the fragmentation of the working class. The article develops a theoretical-conceptual analysis on Solidarity Economy and Public Policies related to selective collection and then carries out a comparative empirical research, with two concrete experiences, in solid waste selective collection cooperatives operating in the city of Belém, state from Pará: the Terra Firme Recyclable Materials Collectors Cooperative (CONCAVES) and the Aurá Professionals Cooperative (COOTPA). The dynamics intended to identify and analyze processes such as the trajectory of the quality of life of cooperative workers, taking into account the risks of reproduction of the precariousness or not of work; and the conquest of administrative and operational autonomy of cooperatives in relation to public policies at all levels or, on the contrary, the reproduction of relations of subordination and assistance.

Keywords: Precariousness of Work, Associated Work, Selective Collection, Public Policies.

INTRODUCTION

This topic of study is relevant in the deepening of researches that carry out a deep analysis on solidarity enterprises, which cover from the moment of their origin to the present day, through the identification of material, social and cultural factors that drive individuals to to join and, above all, to remain. Its objective is to complement existing studies, which are limited to investigating circumstances that, in spite of these workers’ unwillingness, forced them to seek alternatives for work and income, as if the existence of these pressures were sufficient to passively lead them to a certain direction.

Linked to this theme, this study deals with associated work relationships as a mechanism to combat the practice of precarious work and as an alternative in generating work, employment and income to reduce socio economic problems. Therefore, it concerns the Solidarity Economy (ES), which together with public policies, can become an inducing and driving mechanism for social, economic and environmental development.

The article emphasizes the microeconomic approach, as it studies the trajectory of two popular cooperatives, at the same time with a macroeconomic approach, with emphasis on public management in selective collection. It is a dynamic process, as the dynamics of management of two cooperatives and the relationship with the dynamics of public management in selective collection are studied.

It is in this perspective that this new economy can come to stand out in the perspective of the organization of solidary productive chains, constituted by the articulation of self-managed enterprises, urban and rural associations and cooperatives, which contribute to the socioeconomic insertion of subjects historically excluded from public development policies both at regional and national levels (EID et al, 2010).

As a practical and important study for the academic bibliography, a comparative empirical investigation will be carried out in two cooperatives for selective collection of urban and household solid waste located in Belém, in the State of Pará, the Cooperativa dos Catadores de Materials Recicláveis - CONCAVES and the Collectors’ Cooperative called Aurá Professionals Cooperative – COOTPA. These two enterprises are formalized as a cooperative, with the same economic and social base, and it is worth questioning under what circumstances cooperation and socio-productive organization develop together and make work not only a central element, but a differential and its autonomy in in relation to public administration, at its different levels.

At this point, it is important to emphasize the importance in the comparative study between the two selected cooperatives, considering that COOTPA was founded through induction of the Municipality of Belém, while CONCAVES emerged by the initiative of the cooperative members themselves. This difference will be relevant for the investigation process, considering that the focus of this Dissertation deals with a discussion between Solidarity Economy and Public Management, focusing on the autonomy or dependence of cooperatives on the incentives and benefits provided by the public power to develop the activities of these enterprises and its cooperative workers.

As a questioning of the research, we sought to answer: if popular selective collection cooperatives, created by the workers themselves, without participation, in an inducing process by the Municipal Public Administration, during their initial formation, guarantees administrative and operational autonomy, remains and expands this autonomy, over the years, reaffirming the principles of Solidarity Economy, compared to induced cooperatives?

The general objective of the research is to analyze whether popular cooperatives are a positive alternative to the problem of precariousness of work and whether, over the years, the achievement of administrative and operational autonomy of cooperatives occurs, in particular of collectors in selective collection in relation to public Management. For this, we intend to identify and analyze, through the study of two comparative cases, considering the analysis of the professional and personal trajectory of the associated workers in the spaces of work and family reproduction.

As specific objectives, it aims to carry out: a) bibliographic review with contemporary authors who deal with the theme Solidarity Economy and Labor Economics related to Public Management articulated with the activities developed by these cooperatives, with emphasis on the theme of decision-making processes, work relations and at work, the construction of full or relative autonomy, welfare practices, qualification policies; b) analyze the professional and personal trajectory of associated workers, in the spaces of work and family reproduction, in two cooperatives of selective collection collectors in Belém, CONCAVES and COOTPA, related to changes in the quality of life and analyze the trajectory of orientation management of cooperatives, under study, centered on the issue of administrative and operational autonomy focused on subordination to public management or on deepening the autonomy and self-management of these workers.

Its justification consists in the possibility of contributing, for a better understanding, about the dynamics of the collective management of solidary economic enterprises, specifically, in the segment of selective collection of urban and household solid waste, regarding the organization, the processes related to the quality of work , and the role of the government as a supporter of these experiences.

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

2.1 CAPITALIST RESTRUCTURING, EMERGENCY OF ASSOCIATED WORK AND SOLIDARITY ECONOMY

As a reaction to the devastating consequences caused by capitalism, in the socio-political-economic scope, materialized in the growing rate of unemployment and precariousness of work, the emergence and maturation of social movements and self-managed economic organizations around the world can be observed, as mechanisms, based on workers’ resistance and opposition to capitalist domination, presenting themselves as opposition to its values and practices.

This reaction of workers has historically occurred since the mid-19th century, in the form of self-management cooperatives, bankrupt and recovered companies under workers’ control, among other forms.

In general, the socially excluding structure of capitalism tends to encourage the organizations of associated work. Structurally, these organizations have different characteristics and importance, depending on the time, social, economic and political situation in which workers live.

In the last decades, with the neoliberal, motivator of the unbridled accumulation of capital, the social reality has changed, with the modification of the regional structures of life and work; eviction from institutions and popular movements of resistance to capitalism; encouraging the practice of racism and national conflicts; division of the working class, increasing precariousness of the workforce and the containment of democratic elements present in the political life of society, the State becoming a manager of private business, with a rational character and economic-administrative efficiency (DAL RI, 2010, p. 7).

Ideologically, neoliberal capitalism is contrary to solidarity between the working class and organizations with an autonomous and class character, due to the ideology of social transformation, and which, due to the lack of political force, found resistance for its effective operationalization. However, it did not prevent the resistance actions, on the part of the workers, regarding the devastating capitalist relationship of production, materialized in the creation of associated work units and in the effort to create jobs not based on the criteria of capitalist appropriation.

The creation of cooperatives and self-management companies, by workers, is mainly motivated by unemployment and the maintenance of jobs, and aims to produce an economic surplus for the maintenance of the enterprise and its members.

In this sense, the experiences seek to develop the production and conservation of the work community, which is based on four pillars: a) perspective of replacing salaried work with associated work; b) implementation of an egalitarian income distribution policy; c) differentiated organization of the work process, with a tendency to eliminate the hierarchical structure and bureaucracy; d) self-managed management, through assemblies and work committees.

In this perspective, the relationship between associated work and the solidarity economy refers to the interaction of the working mass associated with a form of production structured in independent and autonomous production units. And as a mechanism to combat the relationship of exploitation and subordination of work to capital, essential to the capitalist work process, it introduces profound changes in the form of organization and management of solidarity enterprises.

The solidary economy, conceptually, is considered a form of organization to generate work and income, as a mechanism for improving the living conditions of those considered poor and miserable workers, through the mobilization, motivation and involvement of these people. Structurally, it manifests itself in collective solidarity enterprises: informal groups, associations, cooperatives, self-managed companies; which, through self-management, guarantee the improvement and maintenance of the well-being of those excluded from formal employment by the capitalist process.

Solidarity economy is determined as a mix of concepts and practices that aims to propose solutions for the crisis of salaried work and for the productive restructuring, starting from the reorganization of work and the ways of appropriation of wealth, coexisting with the economy of capital and if materializing economically through the progress of public development policies.

According to Daniela (2011), in the literature, one can find several terms that refer to the solidarity economy, such as: social economy, popular economy, popular solidarity economy, citizen economy, human economy, labor economy, among others. She emphasizes that there are different experiences and forms of organization in the field of solidarity economy, the perceptions of the authors are also different.

According to França Filho (2002), the expression “solidarity economy” indicates the junction of two historically dissociated notions – economy and solidarity – suggesting the insertion of the solidary element at the center of the elaboration of its activities and economic relations. According to Leite (2009) it is in the current context of the crisis of salaried work that scholars began to detect, since the 1980s, a set of movements focused on the formation of production cooperatives and workers’ associations, in which self-management and which have been recognized by the term “solidarity economy”.

Based on cooperation and human character, it presupposes that technical rationality is focused on social rationality, in which the maintenance of jobs and the fight against the precariousness of work are the fundamental causes of its existence. workers in the decision-making process, acting as main actors in this process.

According to Singer (2004, p. 12), as it has work as its central objective, it can be framed as a Labor Economy, focused on meeting the needs defined by the collective of workers, supported by the training of associated workers and the training methodology. specific to each enterprise.

Historically, the solidary economy was present in society, through solidary and self-managed economic experiences, as an alternative to combat the ills of the capitalist process – concentration of land, income and power -, manifested through social movements of workers. However, due to the imprecision and discontinuity of these movements, the solidarity economy did not present expressiveness for the formulation of an effective economy of work and a concrete alternative to the capitalist mode of production.

From the first years of economic activity, it is intended to ensure minimum conditions for the (re)conquest of dignity and subsistence, it is assumed that over the years, with the process of maturation of investments and social cohesion, the impacts are greater on the quality of life of associated families, and in their economic surroundings, effectively contributing to the development of urban and rural locations. (EID et al, 2010).

In this perspective, the solidarity economy permeates the idea of an initiative to satisfy basic consumption and the immediate survival of associated families, and must go further, breaking with the initial process of being just a popular economy. If reduced to this, it finds itself tied to a vicious circle where poor people produce and sell or provide services only to other poor people, without external articulation, partnerships and support from public institutions, closing themselves to the possibility of building small chains. self-managed productive activities constituted by solidary enterprises and expansion of activities, with continued qualification and adoption of social technology, while maintaining its identity as a social movement, expanding its capacity for resistance, within the capitalist mode of production.

Marketing-wise, it presupposes a process of exchanging products and services, based on reciprocal, complementary differences and utility, according to the interests of the parties, establishing a system of economic and social relations favorable to all individuals and enterprises involved in the process.

In Brazil, the solidarity economy, in the form of self-management companies, gained prominence in the 1990s, due to the opening of the market and the bankruptcy of companies in the face of competition from the globalized market, motivated by the process of opening the national market, the third industrial revolution, technological advance and the replacement of the worker by the machine.

With the opening to foreign companies, many national industries with low productive capacity declared bankruptcy, which caused an increase in the number of unemployed in the country. In this scenario, due to the lack of jobs, the struggle of unemployed workers gave rise to the recovery of companies, in bankruptcy, under the regime of self-management.

This is yet another alternative to the growing precariousness in which the world of work finds itself, demanding from workers skills regarding the technical knowledge required in work processes and behaviors regarding the forms of collective management of the cooperative. The national solidarity economy is formed both by small, medium and some large companies, which have gone through bankruptcy processes and which are currently self-managed cooperatives, as well as by small groups of production or services that are still formalized or informal that are structured and maintain their activities with or without support from public policies, university incubators, organizations, among other institutions, whether public or private.

According to Adriano (2010, p. 119), cooperativism in Brazil gained another meaning, from the development of the solidarity economy and the consolidation of companies as production cooperatives, and solidarity economy companies and enterprises gained a different connotation from traditional cooperatives. , due to the economic and political character and the new culture of values and group integration mechanism.

Solidarity cooperativism focuses on the effort to ensure the development and sustainability of enterprises, with the perspective of autonomy in relation to governments, in terms of their form of representation, articulation and action with cooperative workers for the generation of work and income. .

Faced with the change in the world of work, in which continuous pressure from the business community for a new functional profile, more technologically capable and multifunctional, requires, in the field of solidarity economy, the systematization and qualification of cooperative members, to guarantee the effectiveness of solidarity enterprises, based on in the instruction for the practice of self-management, internal democracy, among others. Another characteristic is the limitations and uncertainties in which solidarity enterprises are inserted, both in the legal and public policy spheres. In addition, there is fierce market competition for insertion and maintenance in the market.

Self-management is a fundamental element for solidary enterprises, and requires a cultural change, as this new economy generates a different posture from the one commonly developed, when in the figure of a salaried employee, he becomes an associated worker in a collective enterprise, being necessary the development of solidarity; of collective work; the management of the business itself; the achievement of management autonomy and non-acceptance of intervention by government agencies, developing the capacity for the collective administration of a business.

The development of self-management in solidarity enterprises is a long process subject to contradictions, but it presents itself as an alternative to combat the traditional model of the labor market – mere execution of tasks, with the incorporation of the experience of people/group, in terms of knowledge, values, behaviors, desires and ideas; at the same time as it involves the process of interaction between the individuals in the group. As all workers become responsible for the enterprise, a strategic organizational vision of the business and the knowledge necessary for the maintenance of the enterprise, arising from their experiences, are required.

For the solidarity economy, the human being is the focus of the organization of society, as social, economic and productive relationships are defined. Therefore, it is based on dialogue with the worker and on the insertion of their experiences and anxieties, that is, reality, for its construction.

For Adriano (2010, p. 121), the solidarity economy is a pedagogical path for the autonomous action of workers, the process that leads to the final product and not just the result being relevant. Its development and its principles involve a slow process of education, training, qualification and training in a permanent and integral way.

2.1.1 ASSOCIATED WORK, POPULAR COOPERATIVISM AND SOCIAL CHANGES

Associated work can be identified as part of the movement of struggle in the search for structural and social changes, using cooperation, to overcome the model of exploitation and achieve the process of social transformation.

This transformation process can be interpreted as the continuous stage of development of society, as well as of its productive forces and its social relations, for the construction of an organized society, taking into account the humanist, social and environmental precepts.

In this context, there is the emergence of specific social enterprises – popular cooperatives – as a particular element of workers’ resistance to the advance of capital.

Structurally, the cooperatives initially presented two political currents: the consumer cooperatives, with the purpose of joint acquisition, by the workers, of consumer products; and production cooperatives – as an attempt – by workers – to take control of the work and production process. Both sought the reorganization of the productive process, outside the practices of capitalist exploitation, with a new social relationship based on mutual cooperation.

The cooperative organization naturally tends to internationalize, whatever the economic and social orientation may be, since the first principle of cooperation is association, that is, unity. Its essence is to seek a solution to collective problems through action based on the association, individually, of men and women in cooperative societies; and then, through the conjunction of these cooperative associations in federation; finally the natural course of its evolution leads the organization, through federations of national scope and the agreement for the process of the common interests. (WATKINS, 1973, p.15)

According to Christoffoli (2010, p. 23), traditional, large-scale cooperatives are mostly constituted by collective capitalists, due to the construction of collective production cooperatives, which seek to eliminate only the individual capitalist and, in other cases, the wage labor, but structurally maintaining private property, belonging to a specific group of workers, not covering the entire class.

Insofar as the capitalist legal form of property decisively subordinates all forms that diverge from it, collective forms can only develop their potentialities after the individual private form has been abolished, which can only happen, however, in the of a global social change in the mode of production. The core of the mode of production lies in the class character of state power, whose essential component is the legal form of property. The defense and guarantee of this is the central function of the State in societies divided into classes. (GERMER, 2006, p. 8)

Despite the capitalist precept of private property, in associated work ventures, its essence is in the valorization of life, in the protection of health and the environment, and more intensely, in the fight against monopoly capital and the current economic model.

According to Dal Ri and Vieitez (2010, p. 8), associated work, as a historical movement of resistance to capitalism, was based on the creation, through the union of workers, of a social technology, called collective mass organization – Associated Labor Organizations (OTAs) -, for example, unions, factory committees, cooperatives and associations; who were able to transform production relations into work units.

This associative form of work is closely linked to social change, with regard to the creation and recovery of work units based on relatively democratic production relations, that is, the democratic benefits of associativism are in fact historically relevant, transcending the situation of subalternity or mere complementarity of capitalist activity.

Therefore, social change can be found both in the concrete acts of establishing associated work units and in the theoretical or ideological conclusions that seek to determine its meaning and historical direction. However, here the confluences end. The associated work units present several variants of organization, and theorizations about them reach the point of contradicting each other in their formulations. (DAL RI; VIEITEZ, 2010, p. 72).

The creation of OTAs is closely linked to historical situations of capitalist social formations, such as: political hegemony, bourgeois ideology, revolutionary situation, among others. It was also influenced by broader movements and organizations. These associative enterprises have been present in society since the mid-19th century, however they only gained prominence with the implementation of neoliberalism, due to the growth of cooperativism, the solidarity economy, self-management enterprises, among others; who ideologically defend social equality, with values of freedom and equality.

Five are the characteristics that guide associative work: a) association; b) property; c) power; d) distribution; e) relations with social movements. (DAL RI; VIEITEZ, 2010, p. 69).

The association is developed through the collective organization of workers in work units based on an autonomous collective cooperation system, which differs from the capitalist model in the form of appropriation of the economic surplus of the enterprise, that is, in the form of equal distribution of wealth and of the power generated, in which the decision-making is the responsibility of the general assembly of workers. In the context of OTAs, ownership is defined by associative ownership of workers, that is, it does not allow the individualization of the capital invested in the social enterprise; has a mechanism of socialization and democratization.

As for the power relationship, in the associated work, it focuses on the figure of the general assembly of workers, which decides and regulates the issues related to the solidarity enterprise, dealing with issues since the approval of the statute and rules.

In associated work, there are two basic practices of organizing power, according to Dal Ri; Vieitez (2010): “representativeness and horizontality”, in which the first, despite the assembly being the main body of power, decisions are made, most of the time, by the Administrative Council or Board of Directors elected by the associates. The second, most of the decision is taken in the general assemblies and usually the OTA, has intermediary bodies for sectoral decision-making.

In terms of distribution, there has been a significant change in the way in which wealth is distributed, as a result of changes in the unit of production and the egalitarian or equitable way of appropriating wealth and distributing power characteristic of associated labor organizations or self-management.

The associated work is affirmed by the interrelation and interdependence of relevant elements of democracy and socialization, however its incorporation into anti-systemic struggles is only carried out through an alliance with trade union movements and other popular forces, which guarantee the overcoming of the economic-corporate limitations. This alliance allowed the elevation of the category of force at the hegemonic level, that is, a force capable of contributing to engender another conception of the world on a reflective and practical level (DAL RI; VIEITEZ, 2010, p. 93).

2.1.2 WORKING CONDITIONS AND THE SOLIDARITY ECONOMY

To better understand the aspects of working conditions and their relationship with Solidarity Economy, it is crucial to understand the concept of work, which according to Marx (1983), consists, above all, in a process between man and Nature, in which through actions, measures, human regulation, Nature is controlled. According to Antunes (2000), the realization of the social being is effective through work, which is developed through the bonds of social cooperation existing in the material production process, in which the act of production and reproduction of human life is carried out through work.

With the Industrial Revolution, there were profound changes in the world of work, changing the production base that was rural society, through agricultural production and land ownership, which lasted until the 19th century, to the industrial society based on the production of large-scale goods and power passed to the ownership of factories, called the capitalist mode of production.

“The large-scale use of machines, moreover, breaks the technical unity between work and its tool, inaugurating processes of disqualification of work and devaluation of work that becomes an indelible mark of our production processes” (TEIXEIRA, 2002, p. 17).

With the capitalist mode of production, it provoked intense changes in the work process, in which productivity becomes the center of this process, with work, according to Weber (2003), becoming the very purpose of life, through standardization and mechanization of production that tended to a uniformity of life.

In this process, the work that is governed by the conditions of the capitalist mode of production is degraded, making work a means of subsistence and the workforce a commodity. According to Marx (2002, p. 111), work becomes poorer the more wealth it produces.

In this context, the production of wealth in capitalist society is gradually detached from the use of human workforce that is being replaced by machines, consequently, those who cannot sell their workforce are considered excluded and marginalized.

“The social organization is little improved; that men still allow themselves to be exploited by violence and fraud; and that the human species, politically speaking, is still steeped in immorality (…)” (SAINT-SIMON, 2002 b, p.60).

In an attempt to combat the negative aspects produced by the capitalist mode of production, alternative forms to this mode of work organization emerge, namely the Solidarity Economy. Fourier (2002) discusses the advantages of developing collective work, based on industrial work based on the principle of passionate attraction, with work developed willingly and with freedom by workers, based on participation and proportional distribution of wealth with the working class. , producing an association that would bring economic, social and ecological advantages.

“An organization composed of diverse bodily and intellectual faculties, experiencing physical and moral needs or inclinations, sensations, feelings and conviction” (OWEN, 2002, p. 103).

Singer (2002) conceptualizes that higher education emerges with workers at the beginning of industrial capitalism in combating poverty and unemployment caused by the replacement of the workforce by industrial machinery. At this time, workers began to organize themselves through cooperatives, in an attempt to recover work and economic autonomy, which are basic principles of equality and democracy. This type of association, that is, the solidary company aims to maximize the quantity and quality of work.

In general, ES as an alternative to the model of exclusion and domination of work, in an attempt to rescue human values and more egalitarian societal formation, based on the resumption of autonomy and rescue of work in its full sense: a worthy source of life , in opposition to the capitalist form of work that generates suffering, poverty, operation and human misery.

Analyzing concrete experiences in solidarity economy requires going beyond the importance of the economic results obtained, it requires the recognition of the transformations introduced in other dimensions, such as the emancipation and interaction of the agents involved in the solidarity establishment through economic transformation and cultural, social and political processes brought by them.

It should be borne in mind that the set of experiences is heterogeneous, that is, with varied characteristics, pretensions and actions. Historically, the preponderant motivations for the creation of a solidary economic enterprise are of an economic nature and the issues related to the quality of life, that is, it is precisely to maintain its sustainability concomitantly with gains of an extra-economic nature, preserving the principles of economics. solidarity.

Essential elements for the analysis of concrete experiences linked to ES, it is related to three relational dimensions with the quality of life sought by solidarity agents, namely, a) subjective dimension and health; b) personal growth dimension and c) societal dimension. (BRAZIL, 2011, p. 198).

The first dimension is linked to coexistence and the opportunity to work, denied by the unemployment situation, responsible for a feeling of well-being that leads to extra-economic benefits with repercussions for improved health.

The second portrays the valorization of the human being, instead of capital, is one of the principles of the solidarity economy, as it deals with a substantial gain that can result in deeper changes, as it focuses on the process of personal growth and learning is favorable. to transformations that go beyond individual aspirations and reach collective aspirations.

The third refers to the definition of feeling part of a process of change that transcends the personal level and that concerns the participation in the construction of a project of society.

Rutkowski (2008) states that when working cooperatives are observed, it is detected that the income generated by these enterprises is small, and that this reality prevents investments necessary to improve production, or even difficulties in meeting other needs such as: contribution with social security or build health and education funds. This reality prevents the expansion of the number of members, encourages high turnover among cooperative members, maintains dependence on external support, which ends up undermining the belief in achieving the proposed objectives of generating income and contributing to public policies for urban cleaning. (EID, LAFORGA AND LIMA, 2010).

According to Brazil (2001, p. 185), the main reasons that led to the creation of enterprises are, in the first place, the solidarity economy as an alternative to unemployment, followed by income supplementation and, finally, the associated work converted into motivation for the enterprises. It should be noted that together, the need for work and income accounts for most of the motivations.

Seeing it either as an institutional field of work, be it a target of public policies to contain poverty, or even a new front of struggles of a strategic nature, visions, concepts and practices intersect intensely, questioning each other and promoting the economy. solidarity as an alternative for… the excluded, workers, a development model committed to popular interests, etc.; an alternative, to the deepening of inequities, to neoliberal policies, … to capitalism itself. (GAIGER, p. 1-2).

In 2000, the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics – IBGE identified that there were about 24,500 collectors in Brazilian municipalities, 22% of them under 14 years of age. In recent years, the Public Prosecutor’s Office has acted vigorously with city halls, aiming to prevent children and young people from working in dumps.

According to Eid, Laforga and Lima (2010), the formation of cooperatives of workers who are in the waste recycling sector, the structure and functioning of the recycling market are based on three components: the autonomous collector, who performs the first stage of the process, collects and separates waste in a competitive scenario; scrap dealers, who informally or formally buy recycled products from collectors or cooperatives and sell them to industries or international buyers; industries and international buyers make up the third component of this waste reuse chain, the latter being the major beneficiaries of the entire recycling process.

2.1.3 SOLIDARITY ECONOMY IN THE STATE OF PARÁ: GENESIS, DIFFICULTIES, PERSPECTIVES

The philosophy of solidarity economy, as already discussed, emerged as a questioning about the institutional form of production and reproduction of society and as a collective construction of local/regional development. In this context, it is worth emphasizing the importance of understanding local/regional specificities; investigation and systematization of experiences in order to unify the struggles against neoliberal globalization.

According to Laville (2004) the historical roots of the solidarity economy differ from one place to another, thus differing from one country to another. In Latin America, he states that it is marked by colonization and forms of subordination of work and “welfare practices” that make productive self-management difficult. It is worth mentioning that solidarity practices must be guided by the specificity of each locality, as if guided by foreign forms it brings an asymmetry that makes it difficult to meet the new demands of the social movements engaged in the process.

In Brazil, the solidarity economy stood out in the last decade of the 20th century, with emphasis on the organization of solidarity enterprises (cooperatives, associations and production groups). seeks a new conception of society, evidenced from the 80’s, with the democratic opening.

When it comes to solidarity economy in the state of Pará, historically there are three currents that delimit the initial mark of this movement in the state, the first points to the microcredit policy of the Banco do Povo of the Municipality of Belém in the period of 1997/2000, as the great lever for the origin of the solidarity economy in Pará; the second states that the solidarity economy was already widespread by Brazilian Cáritas, more specifically in the northeast and west regions of the state, called “alternative cooperativism”. The third is that the solidarity economy already existed empirically in many enterprises, however not explicitly identified.

It is considered the first test of a policy to promote higher education, the promotion, through credit lines and incentives for the creation of solidarity associative cooperatives already in 1998 by the Banco do Povo belenense, which enabled the generation of employment and income for the local population and the formalization of impediments linked to the popular economy. Linked to this credit policy, the municipal government also promoted actions for the qualification of workers regarding the formation of cooperatives on the principles of ES, however the qualification provided was insufficient, even generating the weakening of cooperatives induced by the municipality, organized as a promotion mechanism. of socio-productive inclusion of workers.

According to FPEPS (2005), the solidarity economy in the region had its origins in the popular economy, through the Forum of Popular Entrepreneurs in Belém – an initiative with the main objective of contributing to the solidarity organization of the various segments of the popular economy -, which took place in 2000. , aiming to offer support for the attempt to organize the solidarity economy.

Influenced by the debates that took place at the World Social Forum in 2000, in the city of Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, a movement by street vendors on the main avenues of Belém began to form, through the popular economy, an initial milestone in the realization of the economy. solidarity in Pará, which was based on the need to survive the local labor market.

It is worth mentioning that the public actions carried out in 2000 had their objective set only to generate employment and income, in an attempt to mobilize the unemployed and formalize the informal economy and the popular economy, through programs and projects linked to the promotion of entrepreneurship. At this time, ES presented itself indirectly. However, this was the opportune moment for the diffusion of the solidarity economy in the state of Pará, considering the successive organization of events involving several workers, whose purpose was not exclusively to generate work and income, but the search for improvement in living conditions. , based on the concepts of collectivity and solidarity, through the interaction of the movement of popular entrepreneurs.

In this context, the solidarity economy was taking shape in the state of Pará, in which workers of the popular economy started to set up enterprises based on the principles of cooperativism, reciprocity and democracy, in which all members of the group are actively responsible for managing the business.

A concrete example of the performance of ES in Pará is the mobilization of workers installed in the commercial area of Usina do Progresso – a space located in the Reduto neighborhood in Belém – against the Municipality of Belém in its attempt to remove workers from this area, thus prevailing. the guarantee of work.

Another example was the participation of 150 workers in the 1st Meeting of Entrepreneurs in Belém, which took place in 2000, with the support of Banco do Povo de Belém and the Solidarity Development Agency/ADS. The event is considered important for motivating these public servants regarding the importance of speeches and mobilizations of this category for resolution and better performance of their economic activities. From this event, the Forum of Popular Entrepreneurs of Belém emerged.

It is in this scenario that an evolution in the solidary economy of Pará can be seen, through discussions of these entrepreneurs, projects were elaborated aiming at the economic strengthening and organization of these enterprises, which resulted, in 2001, in the provision by Banco do Povo of new lines of more adequate credit and the availability of training and capacity building plans through the National Worker Qualification Plan/PLANFOR – a plan that was part of the national policy for professional qualification.

Another remarkable fact that year was the 1st Public Assessment of the Banco do Povo de Belém, in which it was suggested the creation of Forums for Local Solidarity Development, by neighborhood or groups of neighborhoods, including the theme in the discussions, in order to strengthen the solidarity economy.

In the following year, according to FPEPS (2005), 13 local forums were organized, mobilizing around two thousand entrepreneurs in meetings and assemblies, for the discussion with the institutions that promote the reality of the local economy and the articulation of the entrepreneurs themselves. In the same year, the Popular Council for Social Control was created, with the objective of obtaining partnerships to improve the monitoring of enterprises and the maturity of shared management, in which entrepreneurs should responsibly fulfill the role of active subject of the microcredit policy. popular.

In the same year, several events were promoted by the PMB, among them the Journey of requalification in the management of popular enterprises, which aimed to strengthen the popular economy and gradually introduced speeches for the construction of solidary enterprises together with the realization of the solidary economy. During this journey, proposals for the III Brazilian Meeting on Solidarity Economy were discussed and approved.

At the III National Plenary of Solidarity Economy, Pará was a reference in the debates and in the presentation of proposals for the constitution of the solidarity economy in Brazil. The IV State Plenary of Solidarity Economy focused on discussions on issues such as the relationship between the economy and the generation of work and income and the valorization of the worker. Another important event in the history of the solidarity economy of Pará was the establishment of the Forum of Popular Entrepreneurs of the State of Pará, formed by managers and solidarity enterprises, to discuss their demands.

When the theme ES is discussed in the events, the presence of cooperation, conflicts, negotiations and tensions between the agents of the solidarity enterprises is detected, creating an apparent paradoxical context between, on the one hand, the search for the defense of the collective and, on the other hand, the spontaneous manifestation of power relations in dispute for space. However, despite the differences in the way of thinking between solidarity enterprises, the desire for cooperation always prevails.

In 2007, as a result of the V Metropolitan Plenary of Solidarity Economy, held in 2007106, the solidarity economy was defined in Pará as a movement that strengthens the struggle, union and social equality, through new strategies of social development , economic and cultural, of generating work and income, for a fair and solidary trade, reestablishing the relations of dignity.

It is worth mentioning that the struggles of the solidarity economy movement in Pará, at certain times, take place in a discontinuous and pulverized way, sometimes even for personal and individualized issues, but the importance of this “new” economy for the state is already concrete, which materialized, in 2007, from the creation of the Solidarity Economy Directorate/DECOSOL, in the State Secretariat of Labour, Employment and Income/SETER, formed by the fusion of several solidary agents through forces and struggles for the constitution of the solidary economy, as part of the government’s action agenda.

A concrete action by the solidarity movement in the state was the submission of a proposal for a state law on solidarity economy, which was discussed and revised in a meeting by representatives of solidarity enterprises, as well as managers and advisors, who make up the solidarity economy movement in Pará, like PITCPES. Another important performance of the solidarity movement of Pará was materialized at the World Social Forum/WSF, in 2009, in Belém, with the presence of stands at the National Fair of Solidarity Economy, as well as debates about the areas of interest of the solidarity economy and the creation of primers on social currency – Amazônida, organized by the Solidarity Economy Working Group/GT, founded in 2008 and composed of solidarity enterprises, representatives of the state government and advisory bodies, particularly PITCPES.

It should be noted that despite the advances experienced by the Solidarity Economy movement in the state, there is still a lack of clarification and knowledge of the concepts and their principles by many agents engaged in solidarity enterprises, who despite identifying with this economy, have difficulties in define the Solidarity Economy.

This fact is due to two findings: the first is the non-participation of all solidarity enterprises in courses, workshops, seminars, meetings, plenary sessions. Ventures only appear when they acquire financial and logistical support from event organizers and advisors, or even from promotion policies. The second is the absence or little training and qualification on solidarity economy.

According to the Atlas of Solidarity Economy in Brazil (2005) it points out that among the main forms, regularized, of solidarity economy enterprises, associations are the most representative with the percentage of 52% of all enterprises, followed by informal enterprises with 25%. , cooperatives with 13% and other forms of experiences with 9%[5]. According to Miranda et al (2008), mapping these projects, based on data from the same agency, 44% are located in rural areas, 37% in urban areas and 19% with mixed operations.

In the state, there are some challenges that need to be overcome so that solidarity economy can be implemented throughout the territory of Pará. As an example, there is the creation of effective strategies for the participation of solidarity enterprises located in the interior of the state, based on financial and logistical support to come to events in the capital, for the training of their agents regarding the solidarity economy. These strategies can be materialized through the implementation of regional and local forums.

An important factor would be the change in the culture in relation to collective work, mutual trust, as well as the formation of active leaders in the enterprises and technical and professional training for the workers of the enterprises. To this end, it is necessary that training on solidarity economy be carried out through partnerships with the solidarity economy movement, with regard to the provision of technical assistance and incentive to the movement, together with promotion advisors, for the elaboration of projects that help from the organization of enterprises to their infrastructure for production, processing and marketing of products, together with public policies to support the transport and flow of production.

At the same time, it is necessary to include, in the market of products from solidary enterprises, the creation of public policies and microcredit policies appropriate to enterprises to improve the quality of solidary economy products.

Another challenge is centered on the legalization of the solidarity economy in Pará, through the approval and implementation of the state law on solidarity economy and its actual compliance, independently of government management, as it will be the guiding framework for the actions of the solidarity economy, which aim at the issue environmental, educational and health sustainability in solidarity enterprises. This challenge has already been transformed into an achievement, with the elaboration and debate of the law to promote the popular and solidarity economy in the state of Pará, being considered an advance with regard to the legal framework of the solidarity economy in the state.

Despite the obstacles that still exist in the solidarity economy movement in Pará, some achievements can already be highlighted, such as support for the preparation, approval and implementation of projects aimed at solidarity enterprises in its various productive segments. As an example, there is the Project Center for Training in Solidarity Economy/CFES/SENAES/MTE, which aims to qualify all workers, that is, for managers, advisors and solidary entrepreneurs. As well as the specialization course in Solidarity Economy in the Amazon directed to graduates, public managers, representatives of the solidarity economy movement, that is, workers in the solidarity economy or interested parties who wanted to specialize in the subject.

Another achievement was the creation of DECOSOL/SETER[6], which is still being structured, for the promotion of the solidarity economy in Pará aimed at setting up solidarity enterprises with young people from the Bolsa Trabalho Program, through training/training/professional qualification aimed at collective and family enterprises.

In this scenario, the holding of state fairs of solidarity economy stands out, as well as the participation of enterprises from Pará in fairs and events at the state, national and international level, as a means of creating strategies to strengthen the solidarity economy in the State, as well as as the advancement of the movement through debates and suggestion of actions to promote the solidarity economy. Linked to these events are the holding of state conferences and plenary sessions and the participation of the state of Pará in the National Council of Solidarity Economy with advice and entrepreneurship.

In this context of challenges and achievements, the solidarity economy movement still needs to conquer new spaces, strengthen its struggles and actions for a real participation in the social, political and cultural scope of the state of Pará, in which solidarity and solidarity always prevail. cooperation.

2.1.4 THE LABOR ECONOMY AND THE SOLIDARITY ECONOMY

Conceptually, Coraggio (2000) defines the labor economy as a social economy that focuses on the creation of the collective good and not on the individual interest of individuals, a predominant factor in the capitalist economy. According to Coraggio (2000), this economy is based on domestic activities, such as cleaning, cooking, making clothes, activities that are consumed by family units without going through the market, contemplating a set of activities, including cooperatives.

This economy has its interaction with the Solidarity Economy, as it develops due to the lack of capacity of the capitalist structure to insert a portion of workers in the labor market, as well as the limitation of compensatory public policies in relation to unemployment and the precarious conditions of the work, which provokes a reaction in the excluded population to seek forms of subsistence in domestic enterprises to ensure the reproduction of extended life, which consists of improving the quality of life based on the development of people’s capacities and social opportunities.

Another interaction between these Economies materializes in the concept of social enterprise, which consists of establishments that not only produce goods, but that produce the “social” and value the “person”, in contrast to the devaluation of the capitalist mode of production.

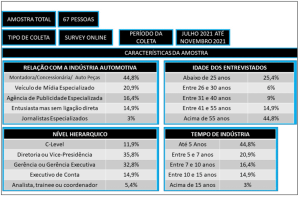

3. METHODOLOGY

This research was carried out in two moments. Initially and throughout the entire investigative process, theoretical materials were sought to support the theme discussed, through a bibliographic review. Subsequently, with the accomplishment of the participant research and case studies, as a mechanism for collecting and processing the information collected from the directors and cooperative members, about the selected cooperatives: Cooperativa de Catadores de Material Recicláveis da Terra Firme (CONCAVES) and Cooperativa dos Trabalhadores do Terra Firme, Aura (COOTPA).

Participatory research occurs with the participation of researchers in communication relationships with people or groups in the situation being investigated. This methodology aims to make researchers accepted by the people or groups researched. The participation of researchers consists of the search for identification of the researcher with the values and behaviors of the group. The case study, on the other hand, consists of the deep and exhaustive study of one or a few objects, allowing its broad and detailed knowledge (GIL, 2007).

Regarding the research objectives, the authors classify them as exploratory and descriptive, with a qualitative approach, because in qualitative research, the researcher is more interested in the process than in the results, examines data intuitively and privileges meaning. These data are complex for statistical treatment and the questions to be investigated are not established through the operationalization of variables, being formulated with the objective of investigating the phenomena of all their complexity and in a natural context (BODGAN; BIKLEN, 1994, p. 16 cited). by BOAVENTURA, 2004, p. 56-57).

The field research with the cooperatives took the form of technical visits to the cooperatives’ facilities, interviews with the directors to verify the management process and the relationship with public policies, in addition, dialogues and application of questionnaires with the cooperative members to identification of professional and personal history, to evaluate management orientation, evaluation of the relationship with the municipal public administration, investigation of working conditions, central themes of this dissertation.

Initially, in May 2012, the aim was to carry out an exploratory research with the cooperatives analyzed to request permission for the development of the research, the maintenance of an initial contact and identification of guiding aspects of the research, such as the history of the cooperatives, the number of cooperative members, legal regularity and identification of directors and cooperative members.

The information collected through the interviews, direct observation to be recorded in a field diary and the documentation provided, as well as secondary data, were transformed into essential elements to respond to the research objectives.

4. DATA ANALYSIS

4.1 COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE EXPERIENCES OF CONCAVES AND COOTPA: DEPARTMENT OF SOLID WASTE (DRS) AND THE PUBLIC MANAGEMENT OF SOLID WASTE IN BELÉM

Starting the field research process, it was carried out with the DRS and took place on 02.28.2013, the interview with Ms. Elvira Pinheiro de Oliveira, Coordinator of Social Projects and Environmental Education.

The Solid Waste Management of Belém is developed by the Municipal Sanitation Department, with the DRS being responsible for all plans and actions for urban cleaning and solid waste management in Belém, among these attributions we highlight the cleaning of public roads, the weeding , channel cleaning, culverts, environmental education and selective collection.

The Solid Waste Policy of Belém focuses its action linked to Rede Recicla Pará (RRP)[7] and Association of Collectors of Selective Collection of Belém (ACCSB)[8], which currently has a shed provided by the City Hall located on Canal São Joaquim , in the neighborhood of Val de Cans. All recyclable material, such as paper, plastic, aluminum, must be taken to the shed. This material is collected in the streets, and that, if it were not the correct destination, could become garbage, generating environmental impacts. But after analysis and sorting, everything must be recycled.

In this scenario, the City Hall has a specific action plan: firstly, it is responsible for the development of environmental education work in the neighborhoods of Belém, to later proceed with the effective activity of selective collection. Only after applying these procedures does the collector enter the selective collection process to collect solid waste. At first, the DRS accompanies the collector in the household collection in order to guide the correct and efficient collection, so that later he can continue his activities independently, aiming at the self-management of the cooperatives.

The first phase of the Solid Waste policy that is being carried out, which is the environmental education carried out door-to-door with the residents of Belém, with a view to highlighting the importance of selective collection and how it should be carried out. This phase was carried out in the districts of Umarizal, Nazaré, Marambaia, Pedreira and Souza. Currently, it is expanding to the Providência, Promorar and Paraíso dos Pássaros housing projects.

Regarding the process of promoting and encouraging the creation of Cooperatives responsible for selective collection, this is non-existent in the current municipal policy, given that the only support that is made available by the City Hall to existing cooperatives is related to the need for logistical support The DRS has 06 (six) collection trucks that are available for loan to cooperatives duly registered and regularized. When vehicles are assigned, there is a need for monitoring by a municipal inspector to prevent the truck from being diverted to other activities, other than selective collection.

According to the interviewee, the first effective Project developed by the Municipality for selective collection in Belém took place in 2004 with the figure of the Voluntary Delivery Post, which was not successful for several reasons, including the lack of commitment of companies and residents in carrying out the separation of organic and recyclable and non-recyclable waste, which made selectivity difficult, in addition to the action of vandals who broke the selective collection bins installed by the City Hall.

Given this reality, the policy was replaced by the current proposal for environmental education and door-to-door collection, with the distribution, in 2007, of 60 metalon carts to collectors and cooperatives linked to the city hall by Rede Recicla Pará and Associação de Catadores da Coleta Seletiva. of Belém, in which 50% are already deteriorated.

When asked about the existing difficulties for the effective application of selective collection in Belém, the lack of commitment on the part of the population that is not aware of the importance of treatment and disposal of solid waste, and non-cooperation in carrying out selective collection at home, was highlighted, which ends up compromising the work of the collectors, even after the visit of the environmental education agents of the city hall.

Another difficulty pointed out is related to the department’s logistics infrastructure, which has few trucks for effective selective collection – six as already reported – and when there is a need for maintenance in one of them due to mechanical failures, it ends up interrupting the selective collection in the stretch served by it. There is also a need for more sheds to receive the material collected, to carry out the sorting and disposal of recyclable waste, ideally having one in each neighborhood and not just one for receiving all the waste, as is currently the case.

With the change of public manager in 2013, the DRS hopes that the new administration will add policies and resources for the selective collection activity in Belém. It emphasizes that the first activities related to the restructuring of policies related to waste treatment have already started, carried out by the 100 days project, called “Take care of Belém, take care too”, which aims to clean, first, the neighborhoods of Belém and lead to effective education environment to the residents of Belém. Afterwards, it will be necessary to implement an effective solid waste policy in Belém, with the creation of an effective solid waste management plan, with its own resources, in order to enable integration with other municipalities in the state of Pará.

Finally, he emphasized that currently the Solid Waste Policy in Belém is still in the planning stage, but with the change of the municipal public administration, the aim is to implement an effective Policy, with the realization of selective collection in all neighborhoods of Belém, with the alternation of selective waste collection of non-recyclable waste, on different days, the first of which would be destined for the sorting centers of each neighborhood, where they would be treated and disposed of by cooperatives and thus the effective application of the guidelines and the national legislation for solid waste.

4.2 CONCAVES: FROM SELECTIVE COLLECTION TO ENVIRONMENTAL AWARENESS

To analyze the reality of CONCAVES, a survey was initially carried out with the current president of the Cooperative. Mr. Jonas de Jesus Fernandez da Silva, who is in his second term, each with 4 years, started in 2006 and ended in 2014.

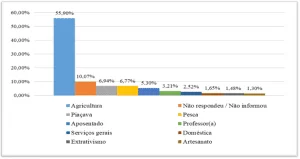

CONCAVES started its activities in 2004, however its effective regularization took place in 2005, with the participation of 13 cooperative members, and currently, it has reached the number of 31 cooperative members, being 27 women and 4 men. Its activity focuses on door-to-door selective collection and sale of plastic, aluminum, cardboard, pet bottles and copper. Of a totally private nature, the idea of forming the cooperative came from the cooperative members themselves, without intervention and encouragement from the public power.

All collectors who work at the Cooperative are considered cooperative members, and do not have any relationship with individual collectors; however, there is a project to expand the Cooperative’s performance, from the moment the Government implements the implementation of selective collection in Pará, more specifically in the metropolitan region of Belém, with the signing of the Conduct Adjustment Term (TAC).

The marketing and remuneration routine is based on weekly productivity. During the week, combined and alternating sales are carried out, that is, so that during the week paper/cardboard is sold, followed by the sale of plastic; then copper interspersed with PET bottles.

Concaves must also bear its fixed expenses, namely, water, electricity, fuel for the truck, IPTU of the headquarters property and the shed that were assigned by a relative of the current president, in addition to expenses with office supplies.

The remuneration proposal depends on the performance and weekly dedication of each member, generating an average of R$ 70.00 to R$ 120.00 per week, with a volume between 08 and 10 tons, paid after calculating the weekly revenue and expenses, however, the goal of a weekly remuneration of R$ 150.00 is sought. For this to happen, there is a need to improve the infrastructure and increase the volume of selective collection to 15 tons.

Each Cooperate receives different values, based on the frequency and performance in the execution of activities, which must be evaluated during the group meeting that takes place on Saturdays.

When asked whether the cooperative offers other benefits outside of remuneration, the Cooperative’s computer was made available for browsing the internet and an allowance for members who become sick and unable to work for a week.

As for training, they are carried out through an agreement with institutions, such as the Cataforte Project[9]; OACB and Cempre (Business Commitment to Recycling)[10].

In carrying out the selective collection activities, personal protective equipment (PPE) is used, which were donated to the Cooperative through the Socio-Productive Project developed by the Coca-Cola NGO, such as: gloves, boots, masks, uniforms, goggles , hats and sunscreen.

The working day is 8 hours per week from Monday to Friday, from 8:00 am to 12:00 pm and from 2:00 pm to 6:00 pm, and on Saturdays from 8:00 am to 12:00 pm, in which meetings are held for accountability, weekly payment and planning of activities for the following week, in addition to the division and distribution of tasks. Exceptionally, cooperative members meet on Sundays, but only when there is a need for events and collecting extra material.

In addition to the weekly meetings that take place on Saturdays, meetings are held, with recognition of ATA every 02 years, to discuss the expectations and plans for the future of CONCAVES, as well as the deliberation to welcome new members.

The material collected is obtained mainly through door-to-door collection, with the support and collaboration of residents of the Terma Firma neighborhood, and through agreements and contracts with public and private institutions, namely, UFPA, Banco da Amazônia, Instituto Evandro Chagas, Caixa Econômica Federal, Companhia das Docas do Pará, SEAD, Banpará and Iterpa.

The division of work among the cooperative members occurs equally and through a rotation of activities, according to the physical state of the cooperative member and volume of work, being the distribution as follows: 1) 02 cooperative members stay in the office in the administrative sector, to attend to the telephone, receive people and proposals for partnerships, in addition to updating information on the cooperative’s website and facebook; 2) 04 leave in the truck for collection at partner and partner institutions; and 3) the others stay in the shed to carry out tasks of collecting, sorting and disposing of the material.

The main source of existing conflicts is linked to the low remuneration obtained with the work developed, in addition to the dissatisfaction with some cooperative members who are not so committed and still do not understand the meaning of collective work and that the cooperative belongs to all cooperative members.

The main difficulty faced is the lack of recognition of the importance of the work developed by the cooperative – solid waste collection -, as an environmental protection agent, as well as the lack of a physical and effective structure for the implementation of public policies aimed at the work of the collector.

The prospects and challenges for the future are linked to the new efforts of the new Mayor of Belém, who held a meeting with CONCAVES and is prioritizing the activity of cleaning and disposing of solid waste in Belém. Although they are all legalized and regulated, there is still no line of financing available, however there is an analysis on the possibility of obtaining a loan to improve the physical structure and purchase of equipment that maximizes the activities developed, as they currently only have a scale and a truck that were provided by SEDES, a factor that limits productivity.

Another perspective is the signing of a Project with the Fundação do Banco do Brasil, in which three containers and 01 vehicle will be donated to CONCAVES for the development of its activities.

As for the history of the cooperative, the 13 cooperative members who founded CONCAVES were collectors before the cooperative was formalized. After the collective success and visibility of CONCAVES in the neighborhood where they operate, other members joined the cooperative, even though they had never worked as waste pickers before, either due to financial need or lack of options in the job market.

As the main difficulty faced by the cooperative in the formation process, the high cost for regularization and bureaucracy was highlighted, along with the low understanding of the importance and recognition of the work of the collector.

Over time, there have been significant changes in the work developed by CONCAVES, based on the support of the population of Terra Firma, who, after several works to raise environmental awareness and the importance of selective collection, carried out by the Cooperative itself, started to separate the garbage at home. , facilitating the work of collectors. In addition to these factors, it was possible to verify that the execution of an agreement and contracts with public and private bodies and institutions for the collection of recycled material helped to increase the cooperative’s productivity.

Within the production process there are two bottlenecks; the first linked to the non-performance of selective collection by the general population that mixes organic waste with recyclable and non-recyclable materials and; the lack of logistical structure, represented by the lack of more trucks and equipment to collect a greater amount of solid waste and the low value received from the sale of recycled material that ends up not adequately remunerating the collector for the work performed.

Another difficulty encountered is the lack of support from the public authorities, especially from the DRS, which is the sector responsible for solid waste management in Belém.

Analyzing the first aspect of the research, regarding the achievement of administrative and operational autonomy of the cooperatives in relation to public management, CONCAVES began its activities on the initiative of the cooperative members themselves without interference from the Government and throughout its trajectory it remained independent of the interventions government agencies to maintain their activities.

Moving on to the analysis of the trajectory of the workers’ quality of life, and considering that the cooperative members throughout the cooperative’s trajectory, there was an improvement in the quality of life regarding the aspect of recognition within the work environment and an alternative to earning income, taking into account the shortage of vacancies in the labor market.

In fact, most members did not have a formal job before joining the cooperative, with the exception of one member.

Within the trajectory of CONCAVES, all its members chose to become part of the cooperative, both at the invitation of the current president, Jonas, and on their own initiative; The vast majority feel motivated and satisfied with the work they do, as the importance of selective collection work for the future and the economic and systematic changes that have been taking place in this activity is passed on to everyone.

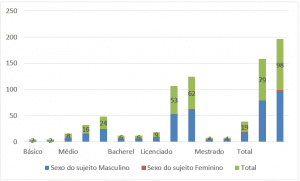

An important fact to note is that most of the cooperative members studied until completing high school or are still studying, so they aim to study at a higher level in the area of the environment to use the knowledge obtained in their work environment.

Economically, the average salary does not reach a minimum wage for each member, a factor that sometimes discourages some workers from looking for intermediate occupations to supplement the main income taken from the cooperative, such as manicure services, graphic assistants, catalog sales, among others. others.

With the low income obtained from the work of the cooperative member, the remuneration can only cover basic expenses: water, electricity, transport, in some cases it allowed the acquisition of appliances, such as a blender and television. None of the cooperative members have a bank or credit account in the city, in the form of a credit card, except in cases where they have a Yamada card.

Considering that the cooperative members are residents of the neighborhood where CONCAVES is headquartered, most go to work on foot or by bicycle. As for housing, there is a part of the cooperative members who have their own house and others who live with relatives; however, most live in rented houses.

Participation in courses, lectures and seminars were held by all when they joined the cooperative and whenever new courses were possible. However, few took the professional courses.

Regarding the decision-making process, the answers were unanimous, each and every decision on activities and decisions is taken collectively. The president gathers the possibilities and partnerships to be signed, discusses with the cooperative members and divides the tasks and actions to be carried out, with everyone’s consent, in the weekly decisions made on Saturdays.

When investigating the difficulties faced to maintain the cooperative, the lack of infrastructure and equipment was highlighted, followed by the low monthly remuneration taken from work. Another item highlighted was the low commitment of public management to the selective collection activity, which ends up becoming an obstacle in carrying out this activity instead of helping and supporting solid waste collectors’ cooperatives.

As for the evaluation of the current administration, it is considered by the cooperative members as “clear, transparent, and makes everyone part of the cooperative” (sic). And the current applicant presents the characteristics of a good director, judged by the cooperative members: “having leadership, authority, clarity in the distribution of tasks and the financial part of the cooperative and a line of command” (sic). As for the evaluation of the work and the cooperative members, the general assessment is that “they are good cooperative members and that the improvement must be based on greater commitment, with greater collectivity in the development of activities and enjoying what they do to value the profession of collector” ( sic).

As a perspective for the cooperative, they aim at: “a better infrastructure, effective support from public management and an increase in the remuneration obtained” (sic).

Unlike CONCAVES, COOTA in its constitution process, in 2001, was induced by municipal public management, in the government of Edmilson Rodrigues. Initially formed by 32 separate collectors who worked directly with selective collection and sale of recycled material collected in the Aurá dump, they received the proposal to create a selective collection cooperative that aimed to add improvement in the development of the activities of the collectors.

Initially, through the agreement signed between the city hall and the Cooperative, a scale was installed inside the Aurá, in which 10% of the value of all the material that leaves the dump was destined for COOTPA. A shed, equipment – press and conveyor – and vehicles – crane and truck were also made available. However, with the change of government, the agreement was undone and the Cooperative was withdrawn from Aurá, having to leave all equipment and vehicles. From then on, COOTPA lost its incentive and connection with the public power, moving its headquarters to a land owned by the former president, Mara.

The biggest difficulty presented by the Cooperative was the administrative discontinuity, the first two administrations, from 2001 to 2004 – Jairo Ramos and 2005 to 2012 – Mara Suely Martins, were very unstable and marked by internal conflicts and harmful to the Cooperative, which almost ended its activities in 2012, when, through the General Assembly, the 22 remaining members and currently linked to the cooperative, met and decided to withdraw the administration of the cooperative from the then president Mara and elect a new administrative council, chaired until today by Maria Fernanda Leal Ribeiro .

After the removal of COOTPA’s headquarters from within Aurá, four went to the headquarters: 1) shed in nova vida, in 2008; 2) the backyard of the former president’s house, Mara, and 3) the last and current shed rented in the Fazendinha community, in the neighborhood of Terra Firma, which, due to the rent adjustment that will take place in 2013, is considering the possibility of moving of physical space.

Working in the collection, sorting and sale of recycled products – plastic, aluminum, pet, cardboard, pet, iron and copper – which are sorted and packaged for sale that takes place weekly. In addition to the 22 cooperative members, 13 women and 9 men, COOTPA currently also has the support of self-employed collectors who work linked to the cooperative and their remuneration is equivalent to the days worked and the volume of material collected and available for sale.

The current production structure is carried out, via door-to-door collection in the Águas Lindas neighborhood and through a partnership maintained with public bodies, via a six-month contract, namely, UFPA, Public Ministry, Banco do Brasil, Instituto Evandro Chagas, Banco da Amazônia and Caixa Econômica, with a weekly working day, from Monday to Friday from 7:30 am to 12:30 pm, with working hours in the afternoon and on Saturdays, when a search for material is scheduled from a partner. Most contracts with public bodies are shared with CONCAVES, in which the collection of material is divided month by month between the cooperatives.

The work is carried out with proper protection by personal protective equipment, such as gloves, boots, masks, uniforms, goggles, hats and sunscreen, received through donations from the Coca-Cola NGO. However, despite having these equipment in stock, not everyone uses it.

Decisions and accountability are carried out fortnightly, in a clear and transparent way, in which all notes and notes on expenses are presented and comforted with revenues, generating a surplus that is divided equally among the cooperative members. Sales of the collected volume are carried out fortnightly.