ORIGINAL ARTICLE

DIAS, Claudio Alberto Gellis de Mattos [1], ARAÚJO, Maria Helena Mendonça de [2], SILVA, Anderson Walter Costa [3], OLIVEIRA, Euzébio de [4], DENDASCK, Carla Viana [5], FECURY, Amanda Alves [6]

DIAS, Claudio Alberto Gellis de Mattos. et al. Domestic violence against women in the state of Tocantins, Brazil, between 2014 and 2018. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year. 07, Ed. 11, Vol. 02, pp. 05-14. November 2022. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/health/violence, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/health/violence

ABSTRACT

A practice that could lead a person to harm, internally or externally, may be considered violence. Violence against women is a public health issue. In a historical context, the woman was socially subjugated to the will of the man. In Tocantins, as in other parts of the country, domestic violence against women tends to be perpetrated by spouses or people close to them. This work aims to analyze the situation of domestic violence against women in the state of Tocantins between 2014 and 2018. The majority of the female population is not aware of their legal rights or the laws that support them. They are emotionally dependent on their partner and social inequality and little study make them preferred targets of domestic violence. The majority of TO women declare themselves brown and find themselves in social, intellectual and financial vulnerability. Full trust in the spouse and close acquaintances exposes the woman to episodes of domestic violence. Finally, the current pandemic situation seems to increase episodes of this type of violence.

Keywords: Violence, Femicide, Woman.

INTRODUCTION

Any practice, psychological or physical, that can lead a person to internal or external damage, using deprivation in any way, threats, in a social or private context can be considered violence (Silva et al., 2020).

According to Machado et al. (2020) violence practiced within environments considered safe by the victim does not respect social class, ethnicity, gender, religion, age group or education.

Violence against women is a public health issue, taken care of by the federal program in Primary Health Care (APS)[7]. Primary care deals with this type of violence because it is considered “the gateway to the Unified Health System (SUS)[8]”, it works with the family and is able to monitor and provide assistance on an ongoing basis, because it also aims at prevention (D’oliveira et al., 2020).

In a historical context, the woman was socially subjugated to the will of the man, usually the husband. In modern society, intrafamilial tension points have been modified. The conquest of the labor market and the increase of female work in the composition of family income have become points of friction in a patriarchal society. Sexual freedom and birth control too. These factors, combined with drugs, alcohol and psychological disorder, are an integral part of the factors that lead women to suffer violence (Diamante and Silva, 2020).

According to the law – nº 11.340, in its 7th article, there are several forms of violence that women can suffer within the walls of their own home (Medeiros and Ferrete, 2020):

I – a violência física, entendida como qualquer conduta que ofenda sua integridade ou saúde corporal;

II – a violência psicológica, entendida como qualquer conduta que lhe cause dano emocional e diminuição da autoestima ou que lhe prejudique e perturbe o pleno desenvolvimento ou que vise degradar ou controlar suas ações, comportamentos, crenças e decisões, mediante ameaça, constrangimento, humilhação, manipulação, isolamento, vigilância constante, perseguição contumaz, insulto, chantagem, violação de sua intimidade, ridicularização, exploração e limitação do direito de ir e vir ou qualquer outro meio que lhe cause prejuízo à saúde psicológica e à autodeterminação;

III – a violência sexual, entendida como qualquer conduta que a constranja a presenciar, a manter ou a participar de relação sexual não desejada, mediante intimidação, ameaça, coação ou uso da força; que a induza a comercializar ou a utilizar, de qualquer modo, a sua sexualidade, que a impeça de usar qualquer método contraceptivo ou que a force ao matrimônio, à gravidez, ao aborto ou à prostituição, mediante coação, chantagem, suborno ou manipulação; ou que limite ou anule o exercício de seus direitos sexuais e reprodutivos;

IV – a violência patrimonial, entendida como qualquer conduta que configure retenção, subtração, destruição parcial ou total de seus objetos, instrumentos de trabalho, documentos pessoais, bens, valores e direitos ou recursos econômicos, incluindo os destinados a satisfazer suas necessidades;

V – a violência moral, entendida como qualquer conduta que configure calúnia, difamação ou injúria.

In Tocantins, as well as in other parts of the country, domestic violence against women tends to be committed by spouses or people close to them, which disfavors legal punishment for the offender (Souza, 2019). In this sense, law number 11,340 of 2006, called the Maria da Penha law, and law 13,104 of 2015, called the Feminicide law, were a step forward in Brazilian legislation for the protection of vulnerable women (Alves and Mathias, 2020; Tatebe and Prosdossimi , 2020).

OBJECTIVE

To analyze the situation of domestic violence against women in the state of Tocantins, Brazil, between 2014 and 2018.

METHOD

According to Schneider et al. (2017) qualitative and quantitative research complement each other and improve the analysis and discussion of what is studied.

The data for the production of this article were taken from the Ministry of Health/SVS – Notifiable Disease Information System – Sinan[9] Net, on the page of the information technology department of the Brazilian Unified Health System – DATASUS[10].

Data on domestic, sexual and/or other violence in the state of Tocantins, Brazil, from 2014 to 2018 were selected. These data were organized in spreadsheets and analyzed in the form of graphs.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The data arranged in figures are described and analyzed below.

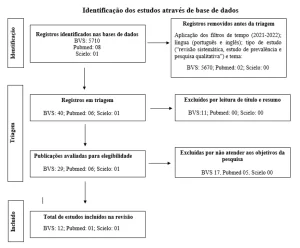

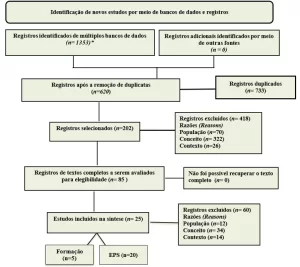

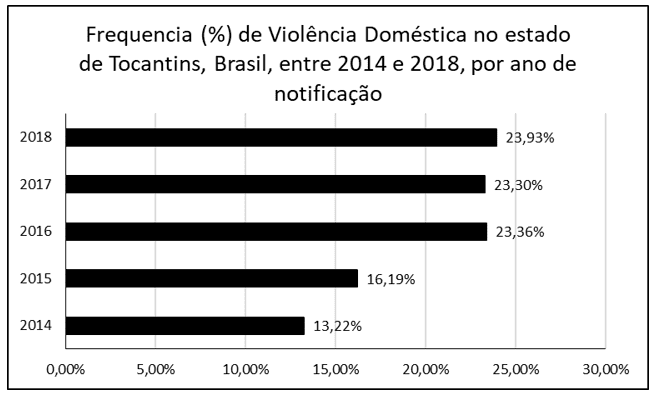

Figure 1 – The figure shows the frequency (in percentage) of cases of domestic violence in the state of Tocantins, Brazil, between 2014 and 2018, by year of notification

The graph above shows a small increase in the percentage of domestic violence in Tocantins (TO) between 2014 and 2015. In the following three years (2016, 2017 and 2018) there was a significant increase in cases of violence.

Possibly the increase in cases of domestic violence is due to a better understanding of women and their neighbors and family members about the legal rights that protect them. This may have generated a greater number of complaints and an increase in registrations (Lemes, 2020; Nascimento, 2020).

This does not seem to mean that there has been a decrease in the number of cases of domestic violence, especially those committed against women. Brazil still ranks seventh among the 83 most violent countries in the world for women, and civil society therefore has to take sides against this type of abuse (Lemes, 2020).

However, the social isolation imposed in the period of the COVID-19 pandemic can worsen this situation, since there is forced cohabitation in this period, the stress caused by economic reasons (worsened in classes with lower education and income) and fear (Vieira et al. , 2020).

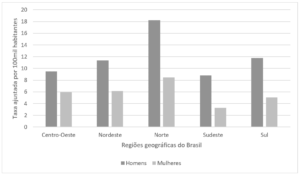

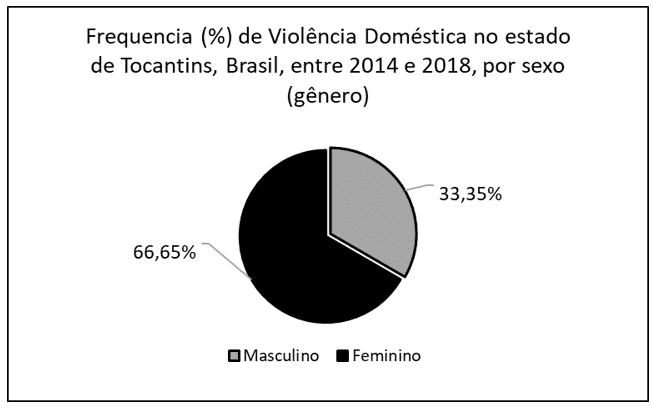

Figure 2 – The figure shows the frequency (in percentage) of cases of domestic violence in the state of Tocantins, Brazil, between 2014 and 2018, by sex (gender)

Data show that, when analyzing the percentage of domestic violence in TO, females are more affected (66.65% of cases) than males (33.35% of cases).

In her article, Nascimento (2020) indicates that there may be a female contribution in continuing the hostile process against herself, as there is little or no consequence for the aggressor. Society imposes well-defined genders and roles for them, in addition to those that are natural genetic attributes. There is no discussion about how each genre has its place in modern society and how each one has occupied different spaces from the other, which causes a lot of social tension.

However, social inequality and the lowest level of education can lead the majority of the population to be unaware of existing protection laws (Silva et al., 2021). Despite the increase in the number of cases, possibly driven by the increase in the number of complaints, women are still more vulnerable (Lemes, 2020).

In the current pandemic, this situation is expected to worsen. Isolation seems to increase the level of stress, depression and violent social behavior, which impacts on domestic violence against women (Oliveira et al., 2020).

In a study carried out with 100 women from Araguaína, TO, it was found that 32% remained within the abusive relationship due to the feeling of emotional dependence, and 23% stayed for fear of threats. Another 14% due to financial dependence, 7% due to children and 1% due to shame (Morais and Levorato, 2020).

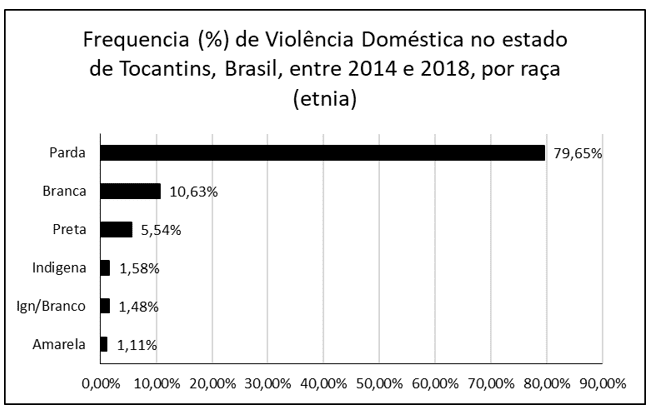

Figure 3 – The figure shows the frequency (in percentage) of cases of domestic violence in the state of Tocantins, Brazil, between 2014 and 2018, by race (ethnicity)

As we can see, the self-declared brown race (ethnicity) suffers the highest percentage of domestic violence in the state of TO (79.65% of cases). In much smaller numbers are the white race (10.63% of cases) and the black race (5.54% of cases).

Violence against women violates human rights. The variation in the relations of production and distribution of goods according to skin color deepens racism and social inequality, even in a mixed-race country like Brazil (Medeiros and Machado, 2021).

Income also becomes an important factor in inequality and, therefore, lower levels of education and less knowledge of their rights as citizens(ã). Earnings by gender, between 2006 and 2013, were lower among women and among self-declared blacks/browns (Ferreira and Pomponet, 2019). Without knowledge of the laws and social rules and without resources to support themselves (or themselves and their children), many women remain in a vulnerable situation (Moreira et al., 2020), which explains the massive difference in violence by self-declared color.

In the state of Tocantins, the majority of the female population declares itself to be brown. This number of self-declarations may explain the vast majority of brown women affected by violence in this state (Morais and Levorato, 2020).

In a survey, numbers show that in TO the types of violence suffered by brown women are: moral (23%), psychological (20%), physical (12%), sexual (7%) and property (2%).

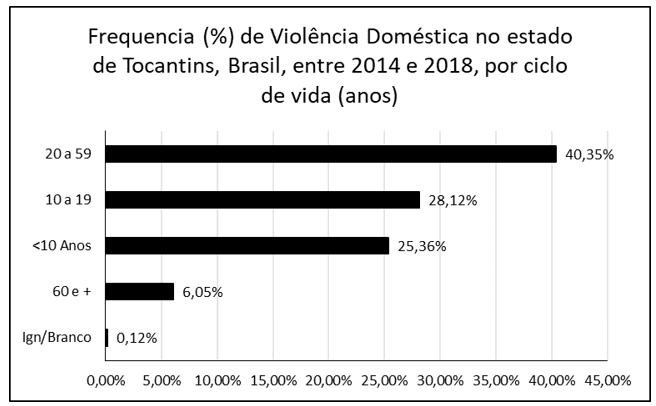

Figure 4 – The figure shows the frequency (in percentage) of cases of domestic violence in the state of Tocantins, Brazil, between 2014 and 2018, life cycle (years)

When we look at the period of life in which domestic violence is suffered in TO, we see that the highest number of victims are between 20 and 59 years old (40.35% of cases), followed by pre-adolescents and adolescents (28.12% of cases) and by children and babies (25.36% two cases).

The age group with the highest rate of cases comprises individuals who are usually in the labor market, whether formal or informal. For women, the age between 20 and 39 comprises the period of greatest professional activity, as well as the reproductive period and care for their children. Women at this age tend to be the majority of victims of domestic violence. This situation has a negative impact on their ability to work, sometimes leading to job loss (Bitar et al., 2020).

In a study carried out in Palmas, Santos et al. (2020) suggests that violence against children is, like violence against women, present in the home and is conducted by parents or acquaintances. Female children, in this capital, suffer greater abuse, which causes countless and irreparable problems in this woman’s adult psyche.

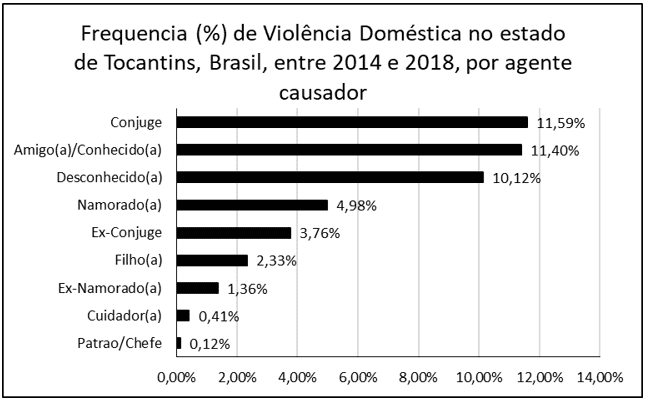

Figure 5 – The figure shows the frequency (in percentage) of cases of domestic violence in the state of Tocantins, Brazil, between 2014 and 2018, by causative agent

As for the causative agent of domestic violence in Tocantins, spouses (11.59% of cases), friends or acquaintances (11.40% of cases) and strangers (10.12% of cases) are among the main groups that practice this type of crime.

It is estimated that many women (approximately 33%) of reproductive age worldwide experience domestic violence committed by an intimate partner (Vieira et al., 2020).

In TO, some percentages corroborate the idea that violence coexists with women in their homes. Of the aggressions against university women, 13% were committed by boyfriends, 11% by acquaintances, 8% by uncles, 7% by brothers, 6% by fathers and 6% by husbands (Morais and Levorato, 2020).

CONCLUSIONS

In the majority of the female population there is no awareness of their legal rights or the laws that support them;

Less physical strength, emotional dependence on the partner, social inequality and little education make women the preferred targets of domestic violence;

The majority of TO women, declaring themselves brown, make this race the majority in the research data. But this same group of women is socially, intellectually and financially vulnerable;

The tension generated in marriage by working outside the home, collaboration in household expenses and, consequently, in its rules, and responsibility in raising children, makes economically active women the majority in episodes of domestic violence;

Full trust in the spouse and close acquaintances exposes the woman to episodes of domestic violence.

Finally, the current pandemic situation seems to increase episodes of this type of violence.

REFERENCES

ALVES, P. H. D.; MATHIAS, L. J. Violência Doméstica no Brasil e na Quarentena. ETIC – ENCONTRO DE INICIAÇÃO CIENTÍFICA. Presidente Prudente SP: ETIC. 16 2020.

BITAR, M. A. F.; LIMA, V. L. D. A.; FARIAS, G. M. Retratos da Violência Doméstica Contra as Mulheres no Estado do Pará. Rev. bras. segur. pública, v. 15, n. 1, p. 174-191, 2020. Disponível em: < http://www.revista.forumseguranca.org.br/index.php/rbsp/article/view/1177/390 >.

D’OLIVEIRA, A. F. P. L. et al. Obstáculos e facilitadores para o cuidado de mulheres em situação de violência doméstica na atenção primária em saúde: uma revisão sistemática. Interface (Botucatu), v. 24, p. 1-17, 2020. Disponível em: < https://www.scielo.br/pdf/icse/v24/1807-5762-icse-24-e190164.pdf >.

DIAMANTE, G. D.; SILVA, H. C. E. Violência Contra a Mulher no Contexto Social Brasilero. ETIC – ENCONTRO DE INICIAÇÃO CIENTÍFICA. Presidente Prudente SP: ETIC. 16: 1-13 p. 2020.

FERREIRA, M. I. C.; POMPONET, A. S. Escolaridade e trabalho: juventude e desigualdades. Revista de Ciências Sociais, v. 50, n. 3, p. 267–302, 2019. Disponível em: < http://repositorio.ufc.br/bitstream/riufc/49880/1/2020_art_micferreiraaspomponet.pdf >.

LEMES, A. F. M. As Principais Evoluções da Lei Maria da Penha em seus 13 Anos de Vigência. Revista Jurídica do Nordeste Mineiro, v. 1, p. 1-15, 2020. Disponível em: < https://revistas.unipacto.com.br/storage/publicacoes/2020/393_as_principais_evolucoes_da_lei_maria_da_penha_em_seus_13_anos_de_vigen.pdf >.

MACHADO, J. C. et al. Violência doméstica como tema transversal na formação profissional da área de saúde. Research, Society and Development, v. 9, n. 7, p. 1-15, 2020. Disponível em: < https://rsdjournal.org/index.php/rsd/article/view/3917/3307 >.

MEDEIROS, A. T. S.; FERRETE, B. F. A violência doméstica e seus impactos na sociedade contemporânea. ETIC – ENCONTRO DE INICIAÇÃO CIENTÍFICA. Presidente Prudente SP: ETIC. 16: 1-20 p. 2020.

MEDEIROS, G. F. D.; MACHADO, J. M. K. M. Mulheres negras e violência doméstica: O desafio da articulação de gênero e raça. REIVA, v. 4, n. 2, p. 1-29, 2021. Disponível em: < http://reiva.emnuvens.com.br/reiva/article/view/183/140 >.

MORAIS, S. P. D. S. R.; LEVORATO, D. M. Violência e feminicídio: Refletindo sobre o cotidiano das mulheres matriculadas em um curso de licenciatura da Universidade Federal do Tocantins/Câmpus de Araguaína. Revista São Luís Orione online, v. 1, n. 15, p. 1-29, 2020. Disponível em: < https://jnt1.websiteseguro.com/index.php/JNT/article/view/840/605 >.

MOREIRA, J. M. et al. Concepções de gênero e violência contra a mulher. Ciências Psicológicas, v. 14, n. 2, p. 1-15, 2020. Disponível em: < http://www.scielo.edu.uy/pdf/cp/v14n2/1688-4221-cp-14-02-e2309.pdf >.

NASCIMENTO, R. R. S. D. Violência Doméstica no Brasil: Uma Questão de Gênero ou um Problema Social? BIUS -Boletim Informativo Unimotrisaúde em Sociogerontologia, v. 23, n. 17, p. 1-12, 2020. Disponível em: < https://periodicos.ufam.edu.br/index.php/BIUS/article/view/8469 >.

OLIVEIRA, D. et al. COVID-19, isolamento social e violência doméstica: evidências iniciais para o Brasil. WORKING PAPER SERIES, São Paulo SP, 2020. Disponível em: < https://www.anpec.org.br/encontro/2020/submissao/files_I/i12-18d5a3144d9d12c9efbf9938f83318f5.pdf >. Acesso em: 04/04/2020.

SANTOS, L. F. et al. Perfil da violência contra crianças em uma capital brasileira. Revista Desafios, v. 7, n. 1, p. 1-8, 2020. Disponível em: < https://sistemas.uft.edu.br/periodicos/index.php/desafios/article/view/7400/16513 >.

SCHNEIDER, E. M.; FUJII, R. A. X.; CORAZZA, M. J. Pesquisas Quali-Quantitativas: Contribuições para a pesquisa em ensino de ciências. Revista Pesquisa Qualitativa, v. 5, n. 9, p. 569-584, 2017. Disponível em: < https://editora.sepq.org.br/index.php/rpq/article/download/157/100 >.

SILVA, A. F. C. et al. Violência doméstica contra a mulher: contexto sociocultural e saúde mental da vítima. Research, Society and Development, v. 9, n. 3, p. 1-17, 2020. Disponível em: < https://rsdjournal.org/index.php/rsd/article/view/2363/1885 >.

SILVA, S. B. D. J. et al. Perfil epidemiológico da violência contra a mulher em um município do interior do Maranhão, Brasil. Mundo da Saúde, v. 45, p. 1-10, 2021. Disponível em: < https://revistamundodasaude.emnuvens.com.br/mundodasaude/article/view/1042/1037 >.

SOUZA, N. R. D. O Agendamento de Notícias sobre Violência Doméstica e Familiar no Estado do Tocantins. 2019. 86p. (Graduação). Universidade Federal do Tocantins, Palmas TO.

TATEBE, B. E.; PROSDOSSIMI, L. E. Lei Maria da Penha e Lei do Feminicídio:Considerações Sobre o Enfrentamento à Violencia Contra as Mulheres. ETIC – ENCONTRO DE INICIAÇÃO CIENTÍFICA. Presidente Prudente SP: ETIC. 16: 1-10 p. 2020.

VIEIRA, P. R.; GARCIA, L. P.; MACIEL, E. L. N. Isolamento social e o aumento da violência doméstica: o que isso nos revela? Rev Bras Epidemiol, v. 23, p. 1-5, 2020. Disponível em: < https://www.scielosp.org/pdf/rbepid/2020.v23/e200033/pt >.

APPENDIX – FOOTNOTE

7. Atenção Primária à Saúde (APS).

8. Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS).

9. Sistema de Informação de Agravos de Notificação (SINAN).

10. Departamento de Informática do Sistema Único de Saúde (DATASUS).

[1] Biologist, PhD in Theory and Research of Behavior, Professor and Researcher of the Degree in Chemistry at the Instituto de Ensino Básico, Técnico e Tecnológico do Amapá (IFAP), of the Programa de Pós Graduação em Educação Profissional e Tecnológica (PROFEPT IFAP) and of the Programa de Pós Graduação em Biodiversidade e Biotecnologia da Rede BIONORTE (PPG-BIONORTE), Amapá pole.

[2] Physician, Professor and Researcher of the Medical Course at the Universidade Federal do Amapá (UNIFAP).

[3] Physician, Specialist in Systems Management and Health Services. Professor, Preceptor and Researcher of the Medicine Course at Campus Macapá, Universidade Federal do Amapá (UNIFAP).

[4] Biologist, PhD in Tropical Diseases, Professor and Researcher of the Physical Education Course at the Universidade Federal do Pará (UFPA).

[5] PhD in Psychology and Clinical Psychoanalysis. Doctorate in progress in Communication and Semiotics at the Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (PUC/SP). Master’s Degree in Religious Sciences from Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie. Master in Clinical Psychoanalysis. Degree in Biological Sciences. Degree in Theology. He has been working with Scientific Methodology (Research Method) for more than 15 years in the Scientific Production Guidance of Master’s and Doctoral Students. Specialist in Market Research and Health Research. ORCID: 0000-0003-2952-4337.

[6] Biomedical, PhD in Tropical Diseases, Professor and Researcher at the Campus Macapá Medicine Course, Universidade Federal do Amapá (UNIFAP), and at the Programa de Pós-graduação em Ciências da Saúde (PPGCS UNIFAP), Dean of Research and Postgraduate Graduation (PROPESPG) from the Universidade Federal do Amapá (UNIFAP).

Submitted: November, 2022.

Approved: November, 2022.