ORIGINAL ARTICLE

LIMA, Douglas Bertoloto [1], FREITAS, Clarissa Pinto Pizarro de [2]

LIMA, Douglas Bertoloto. FREITAS, Clarissa Pinto Pizarro de. Sociodemographic profile of intensive nursing and its relations with engagement and workaholism. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 05, Ed. 12, Vol. 05, pp. 206-220. December 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/health/engagement-and-workaholism, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/health/engagement-and-workaholism

SUMMARY

The aim of this study was to analyze how sociodemographic variables explain the levels of engagement and workaholism in the work of intensivist nursing professionals. An exploratory study with quantitative approach to the data was adopted as a method, conducted with a non-probabilistic sample of nursing professionals working in adult intensive care services in public and private hospitals in the State of Rio de Janeiro. Descriptive analyses of the participants and Pearson correlations were performed between the variables explored through the Software Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 19.0. The results showed that the sociodemographic variables were weakly related or even not related to engagement and workaholism. It was concluded that the weekly workload was positively related to the levels of remuneration of the participants, and this with their schooling. It was also observed that the levels of education of intensivist nursing professionals did not establish a statistically significant relationship with the participants’ engagement indexes.

Keywords: Nursing, intensive care, engagement, workaholism, Occupational Health.

1. INTRODUCTION

In today’s society people invest a large percentage of their time dedicated to work, or even preparing for this purpose. Work occupies a central place in the lives of individuals and is considered a healthy activity, capable of providing people with feelings of well-being, happiness and satisfaction, but the worker’s relationship with their work can also result in negative outcomes (DUARTE, 2018). The outcomes that will happen to the worker may be the result of two distinct states of affective well-being.

There have been many denominations about the welfare construct since the beginning of the studies surrounding it, from the 1960s on. Happiness, satisfaction and positive affections are among the most common designations found in the literature. Well-being is linked to how people think and how they feel about their lives, being structured by affective and cognitive components. The affective component is linked to emotions, such as pleasure and displeasure, and cognitive allows the individual a more holistic analysis of his life (RYAN et al., 2001). Here we will discuss two distinct forms of affective well-being at work, engagement and workaholism.

Engagement is defined as a positive psychological state in relation to work, characterized by vigor, dedication and absorption. Work engagement is considered a pleasurable way that people experience when dealing with their work, culminating in better performance and organizational results. Engaged professionals are motivated and with initiative for work and seek to adapt the difficulties of the work environment, something essential to nursing professionals working in intensive care environments (SCHAUFELI, 2017).

However, this dedication can reach the pathways of exaggeration, leading the individual to a life centered on work and a greater involvement with the organization, generating personal losses. The term workaholism is used to describe this excessive involvement with work. The positive association between burnout and workaholism (ZEIJEN et al., 2018).

Burnout syndrome is a response to chronic occupational stress, which is characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and reduced professional achievement (SCHAUFELI, 2017). In the context of nursing work, professionals directly involved in patient care are the most affected by this syndrome. Burnout and engagement are considered opposite concepts, and should even be measured independently (ROTTA et al., 2019). Based on these statements, hypothesis one of this study is configured: the sociodemographic variable “schooling” will be positively associated with engagement rates.

Among health professionals, nursing workers are the ones who spend most of their time in the patients’ side, being present and experiencing the most diverse and complex situations. Excessive weekly workload, scarcity of human and material resources, conflict relations and ambiguity of roles, reduction in perception and social support are listed as the most common stressors found in the work environment of these professionals (FANG, 2017).

The working conditions of nursing professionals can be examined along the lines of the (Job Demands and Resources Model – JDR). The model of demands and resources of the work proposes that work environments can initiate two distinct processes, that of health commitment and motivational. The motivational process begins with adequate work resources, which encourage employees to achieve their work-related goals. On the other hand, the process of health commitment begins with consistently high work demands that can exhaust employees’ energy resources, leading them to fatigue and health problems (BAKKER et al., 2017).

The intensive care unit consists of an environment for the permanence of critically ill patients who need professionals with specific competencies. The performance of nursing professionals in this environment can be of high emotional, physical and psychic cost, resulting in exhausted, less tolerant and irritable individuals (SOUZA et al., 2019).

A study developed in a national context demonstrated that the nursing workforce is relatively young and continues to rejuvenate. Data state that 40% of the number surveyed is between 36-50 years old and another 38% are in the age group between 26-35 years (MACHADO et al., 2016).

Age is considered by some authors as a predictive factor for the occurrence of workaholism, associating joviality as an attribute to foster the inability to stop working. From this perspective, it is suggested that workaholism decreases as the individual becomes more experienced, evolves in the career or even establishes relationships (ZEIJEN et al., 2018). These statements stimulated the creation of the second proposed hypothesis: the sociodemographic variable “age” will be positively associated with workaholism levels.

The work day is something inherent in the life of any worker, however, in some countries studies show that nursing workers have long working hours, which associated with factors such as low pay increase the perception of physical and emotional demands (OLIVEIRA et al., 2018). Over the years, many definitions have emerged seeking to conceptualize workaholism, most of them sought to associate this construct exclusively with the excessive number of hours worked weekly.

More recently, workaholism has been understood as a multifaceted psychosocial phenomenon, consisting of the dimensions of compulsive work and excessive work, where the professional has difficulty to stop thinking about his work or even to physically distance himself from it (SCHAUFELI, 2017).

Workaholics professionals cannot resist the compulsive impulse to work, differing from engaged workers, who perceive work as something challenging and joyful (ROTTA et al., 2019). This scenario originated the third hypothesis explored: the sociodemographic variable “weekly workload” will not establish significant statistical associations with workaholism and engagement levels.

Although its importance is recognized, it is noted that there is a scarcity of studies on this topic involving intensivist nursing professionals, especially in the national scenario. And in view of this reality, we ask ourselves: is there a relationship between sociodemographic characteristics and well-being levels in the work of intensivist nursing professionals?

In view of these issues, the aim of this study was to analyze how sociodemographic variables explain the levels of engagement and workaholism in the work of intensivist nursing professionals.

2. METHOD

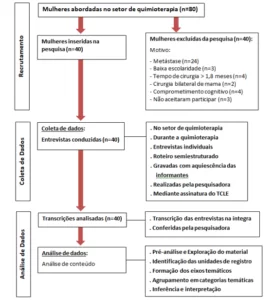

This is an exploratory study, with a quantitative approach, carried out with a non-probabilistic sample of nursing professionals working in Adult Intensive Care Services of public and private hospitals, located in the city of Rio de Janeiro and metropolitan region of the State of Rio de Janeiro. The research subjects were 122 nursing professionals – nurses, technicians and nursing assistants.

The group of professionals was accessed by the method of data collection in person and online. All those approached in person were offered the Informed Consent Form (TCLE). After signing, the participants had access to the sociodemographic and work questionnaire, and the two scales. The online collection was performed via the “Survey Monkey” website, and followed the same requirements.

Ethical procedures were performed according to Resolution 196 of the National Health Council (Ministry of Health, 1996), with regard to research with human beings. The present study was evaluated under the embodied opinion of Salgado de Oliveira University under number 2,998,481 and CAEE: 00379718.9.1001.5289.

In the data collection were applied:

a) Sociodemographic and Labor Questionnaire. This instrument investigated sociodemographic and work information of professionals, such as gender, age, marital status, education, labor relationship, weekly workload, remuneration, among other data;

b) In the evaluation of workaholism levels, the Dutch Workaholism Scale (DUWAS-10) was used; The scale evaluates the addition to work in its two main dimensions, Compulsive Work (CT) and Excessive Work (ET). In total, it consists of 10 items evaluated by a likert scale; The Dutch Workaholism Scale (DUWAS-10), in the Brazilian context, was adapted by VASQUEZ et al., (2018). The analyses of the reduced version DUWAS-10 suggest that both the one-dimensional structure (Addition) (c2(gl) = 207.60 (35); p < 0.001; CFI = 0.93; TLI = 0.91; RMSEA (90%I.C.) = 0.09 (0.08 – 0.10)) or two oblique factors (Excessive Working and Compulsive Work) are adequate (2(gl) = 169.68 (34); p < 0.001; CFI = 0.94; TLI = 0.93; RMSEA (90%I.C.) = 0.08 (0.07 – 0.10)

c) Engagement levels were assessed by the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES). UWES has 17 items distributed in the three dimensions of engagement: vigor (6 items), dedication (5 items) and absorption (6 items). The questionnaire is answered on a seven-point Likert scale (0 = Never/, not once to 6 = Always, every day). The internal consistency indexes of the original version of the questionnaire were adequate (Vigor, α = 0.80; Dedication α= 0.91 and Absorption α = 0.7), (SCHAUFELI et al., 2002).

In the data analysis procedure, it was performed with the help of the Statistical Package for Social Sciences – SPSS, version 19.0, and descriptive analysis of exploratory nature was carried out in order to evaluate the distribution of items, omitted cases and identification of extremes. We analyzed the possible existence of sub-groups or some specificities among the participants and frequency analysis through the Frequency Histogram to identify the characteristics and distribution of the data. The standard deviation and means were also calculated to identify the overall behavior of the sample.

Pearson’s correlation was performed in the search for an understanding of the relationships between the dimensions of the variables and the variables themselves. The intersection of these relationships occurred between the dimensions vigor, dedication and absorption of engagement, the dimensions excessive work and compulsive work of workaholism.

3. RESULTS

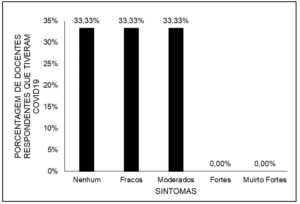

A higher percentage of individuals (38.5 %; n =47), between 27 and 37 years old. It was observed that 36.0% (n = 44) are nurses, 57.3% (n = 70) nursing technicians and 6.6% (n = 8) nursing assistants. The total of 60% (n=73) workers stated that they had up to 10 years of profession, 56.6% (n=69) answered that they had no other employment relationship. There was a prevalence of professionals who reported working between 40 and 50 hours per week. A higher percentage of individuals had high school education. Some results of sociodemographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

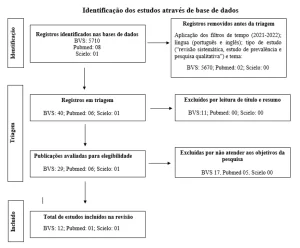

Table 1 – Characteristics of nursing professionals participating in the study. Rio de Janeiro, 2019.

| Variables | N | % |

| Sex

Female Male |

84

38 |

68,9

31,1 |

| Marital status

Single Married Divorced/widowed |

45

47 30 |

36,9

38,5 24,6 |

| Schooling Technical levelGraduateExpertMaster |

32

42 23 01 |

45,9

34,4 18,9 0,8 |

| Category

Nurse Nursing technician Nursing assistant |

44

70 08 |

36,0

57,3 6,6 |

| Continues Studying YesNoThey did not respond |

32

69 21 |

26,2

56,6 17,2 |

| Weekly workload

Between 30 and 35 hours Between 35 and 40 hours Between 40and 50 hours More than 60 hours |

37

21 47 10 |

30,3

17,2 38,5 9,0 |

| Remuneration

1-2 minimum wages 2-3 minimum wages 3-4 minimum wages |

55

24 14 |

45,1

19,7 11,5 |

Source: Elaboration of the authors.

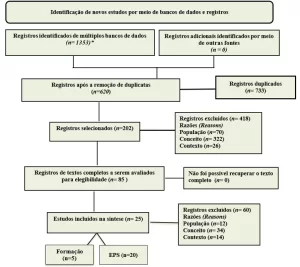

The sociodemographic variable “schooling” showed a correlation of weak and negative magnitude with the levels of engagement of the participants (r = – 0.21; p > 0.05). The workaholism indexes, although average (M= 1.9; DP= 0.5), did not present a statistically significant correlation with the sociodemographic variable “Age”, as detailed in table 2. The sociodemographic variable “weekly workload” did not establish a statistically significant relationship with the variables of affective well-being workaholism and engagement.

Table 2. Correlations between sociodemographic and work variables.

| M | DP | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1 -Age | 34,2 | 8,3 | ||||||

| Two-C.H.S. | 44,5 | 1,2 | 0,21** | |||||

| 3-Schooling | 2,9 | 0,9 | 0,29** | 0,05 | ||||

| 4-Remuneration | 2,4 | 1,8 | 0,21** | 0,31** | 0,66** | |||

| 5-Engagement | 3,3 | 2,9 | 0,04 | 0,04 | – 0,21** | 0,36** | ||

| 6-Workaholism | 1,9 | 0,5 | -0,01 | 0,01 | 0,06 | 0,05 | -0,01 | 0,03 |

Note: ** p < 0,001; * p > 0,05. C.H.S= weekly workload.

Source: Elaboration of the authors.

4. DISCUSSION

Of the 122 participants in this study, 36.0% (n= 44) practice the nursing profession, but 65 (52.0%) participants declared to have education at undergraduate, specialist or master level. This fact demonstrates that a large fraction of nursing technical professionals are qualified above the needs required for their role.

Engagement is considered as a positive, satisfactory and work-related state of mind, which involves commitment and alignment of the professional with the environment and work activity. It is a state of affective well-being, persistent and comprehensive, of motivational and social nature, characterized by three dimensions: Vigor, Absorption and Dedication (SCHAUFELI, 2017).

In this study, it was observed that the means of this construct were high (M=3.3; DP=2.90), considering the entire set of participating professionals. In view of these values and the fact of weak and negative association between the variables explored, we can infer that engagement in intensivist nursing professionals is not strongly determined by their qualification, which does not allow corroborating hypothesis one of this study. In a professional segment where mid-level professionals account for most of the number of workers, this result shows a potential gain, given all commitment and involvement with the work of the participants.

At the same time, there was a strong and positive association between schooling and remuneration indexes (r=0.66; p > 0.05). Nursing professionals perceive that as they seek greater qualification, new challenges and opportunities arise, which results in greater wage gains.

Within the hospital, care units have specific characteristics, which vary according to the type of care performed, the profile of patients and their length of stay. The context of intensive care requires high performance from nursing professionals, which may result in greater involvement with work, regardless of their position (OLIVEIRA et al., 2018).

Engaged workers work and act proactively, are focused on the goals they intend to achieve and are in line with what is good for the organization and its customers. They are usually persistent, even if the work is not following according to plan (BAKKER et al., 2017).

A higher percentage of participants reported being between 27 and 37 years old (n= 47; 38.5%), a proportion approximated to a national study that verified the sociodemographic profile of Brazilian nursing (MACHADO et al., 2016). At this stage of working life, individuals are in full activity of their cognitive, technical and practical functions, playing an important role in the labor market and being willing to work for long hours and periods. However, our results do not allow us to corroborate the second hypothesis proposed, which predicted that workaholism would be more prevalent in this age group.

A recent national study evaluated the age of nursing professionals and their association with work engagement rates and revealed that professionals aged up to 34 and over 40 years showed to be more engaged. (GARBIN et al., 2019). In parallel analysis, we observed that 62.5% (n= 30) of professionals aged up to 37 years stated that they continued to study, seeking higher levels of education.

This panorama associated with the high rates of engagement found in this study helps to understand this group of intensivists as engaged and not workaholics, because they justify their greater commitment to work in search of better wages. Workaholism is characterized by compulsion or the uncontrollable need to work incessantly, however, this need is not sated or directed to material gains. Workaholism is a relatively recent psychosocial phenomenon, but with very negative consequences for workers’ health (ZEIJEN et al., 2018).

The sociodemographic variable “weekly workload” did not establish a statistically significant relationship with the outcome variables workaholism and engagement, corroborating hypothesis 3 of this study. Conceptually, weekly workload is the number of hours resulting from the sum of the working hours on weekdays (BRASIL, 1988). There is an established rule of 08 hours per day, within 44 hours per week, and any reductions should be observed by contract.

It is noteworthy that the Federal Nursing Council (Cofen), through resolution no. 293/2004, regulated a 36-hour weekly work day for care activities and 40 hours per week for administrative activities. In the last 20 years this category has been fighting for a maximum of thirty hours per week, around bill no. 2,295/2000 (OLIVEIRA et al., 2018).

Effectively, what we did in the sociodemographic and labor questioning of this study was to investigate the weekly workload of nursing professionals working in intensive care services. It was found that, on average, 38.5% (n= 47) stated working between 40 and 50 hours per week and 9% (n=10) above 60 hours per week. We highlight that this total reported workday, does not mention or include overtime worked within the hospital institutions themselves, refer only to the official work contracts in force.

Over the past 40 years some definitions have emerged about workaholism, which have restricted the phenomenon to those working more than 50 hours a week. Considering that contemporary work is marked by competitiveness and worker participation, it is evident that a large part of the nursing workforce could fit perfectly into this definition.

However, considering exclusively the number of hours worked is inadequate, since the individual’s relationship with work is more representative than just that, and workaholism has been shown to be a complex multifactorial phenomenon (ZEIJEN et al., 2018). The work demands for nursing professionals in the context of intensive care are multiple and are involved in making many quick decisions, continuously observing patients, and often caring for family members with emotional needs (SANTOS et al., 2007).

Workaholics invest a lot of effort in work, whether physical or psychological, which leaves them with fewer resources to dedicate their families, resulting in sacrifices in their personal lives. In professional practice, workaholism is associated as a potential predictor of Burnout Syndrome (ZEIJEN et al., 2018).

Usually this process results from an additional effort at work, where the employee employs excessive amounts of energy, and this response may vary from individual to individual. In critical work environments such as intensive care, nurses seek to perform functions seeking to do the best they can, sometimes even exhaustion, to achieve the necessary goals and provide quality care (CRUZ et al., 2008).

It should be mentioned that the sociodemographic variables “weekly workload” and “remuneration” established a statistically positive and significant relationship (r= 0.31; p > 0.05). This condition shows that nursing professionals seek better salaries at the expense of a significant and degrading increase in weekly workload, as other studies conducted in the national context (MACHADO et al.; 2016; OLIVEIRA et al., 2018). These results reaffirm the devaluation of nursing professionals, even in a scenario as surrounded by specificities and the need for specialization as that of intensive care (OLIVEIRA et al., 2018; SILVA et al., 2013).

Nursing professionals recognize the hospital environment as a place where it is necessary to keep fragile lives under surveillance and care, and that for this, technical knowledge, skill and competence associated with emotional control are essential for maintaining these lives. In critical units, such as intensive care services, some factors are commonly reported as unfavorable in work processes, such as alarms emitted by cardiac monitors, infusion pumps and mechanical ventilators, loud conversations in corridors, opening and closing doors violently and dropping objects, in addition to excessive traffic of people in the unit (SANTOS et al. , 2007). These factors may increase the work demand of nursing professionals working in intensive care services.

From the conceptual point of view, it should be noted that there is an important difference between demand and weekly workload. Work demands portray the physical, psychological, organizational and social aspects of the work environment and denote psychological and cognitive physical commitment and/or effort, therefore, they are associated with costs for employees (BAKKER et al., 2017).

The characteristics of nursing work itself require multiple demands, which result from the complexity of the care provided, the work environment itself and the demands arising from both the provision of care to patients and the hospital itself. Thus, we established a limitation of this study, since the characteristics of the work demands of the intensivist nursing professionals were not explored, not allowing them to be associated with the variables analyzed.

5. CONCLUSION

The aim of this study was to analyze how sociodemographic variables explain the levels of engagement and workaholism in the work of intensivist nursing professionals. It was observed that the students’ schooling, age and weekly workload did not establish statistically significant relationships with the outcome variables explored.

However, some associations in parallel were statistically significant, and need to be valued in order to preserve the health of nursing professionals in intensive care services. Schooling was not positively related to engagement levels, but was positively associated with weekly workload, and this in turn with remuneration levels. This led us to understand that professionals work longer in exchange for a living wage, reducing their leisure time and family and social life.

This context highlights the need to value the intensive nursing professional in the labor market. It is understood, therefore, that the legal definition of a thirty-hour weekly work day can strengthen nursing science, and also preserve the health of these professionals.

Although it presented mean levels, workaholism was not associated with the age of the participants, a positive factor given the characteristics of the sample in question. However, it was perceived the need to explore and conceptually differentiate weekly workload workload demands. This suggests new research in this field. No associations were perceived between engagement and workaholism, which strengthens the idea of distinct constructs.

The advancement of scientific knowledge in this field can be a pillar in order to offer ancestry in the future over public policies aimed at helping to improve workers’ health. We fully consider that the objectives of this study are fully achieved, and that it contributes in the scientific literature to better understand the emerging phenomenon workaholism and add to other existing ones regarding the engagement construct.

6. REFERENCES

AZEVEDO, Bruno Del Sarto; NERY, Adriana Alves; CARDOSO, Jefferson Paixão. OCCUPATIONAL STRESS AND DISSATISFACTION WITH QUALITY OF WORK LIFE IN NURSING. Texto contexto – enferm., Florianópolis , v. 26,n. 1, e3940015, 2017 . Available from <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0104-07072017000100309&lng=en&nrm=iso>. access on 08 Oct. 2020. puMar27, 2017.

BAKKER, Arnold; DEMEROUTI, Evangelia. Job Demands–Resources Theory: Taking Stock and Looking Forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 2017. Vol. 22, (3), 273–285

BANDURA, Albert. Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. 1997, New York: W.H. Freeman

BRASIL. Constituição federal (1988). Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil. Brasília, DF: Senado, 1988

CAMELO, Henriques; SILVA, Vânea Lúcia dos Santos; LAUS, Ana Maria; & CHAVES, Luciele Dias Pedreschi. Perfil profissional de enfermeiros atuantes em unidades de terapia intensiva de um hospital de ensino. Ciencia y enfermeria, 2013.19(3), 51-62

CARLOTTO, Mary Sandra. Adição ao trabalho e relação com fatores de risco sociodemográfi cos, laborais e psicossociais. Psico-USF, 2011. 16(1), 87-95.

CRUZ, Elisa; SOUZA, Norma Valéria Dantas Oliveira. Repercussão da variabilidade na saúde do enfermeiro intensivista. Revista eletrônica de enfermagem, 2008 . 18(1):1102–13.

DUARTE, Maria de Lucia Custódio; GLANZENR Cecília Helena; PEREIRA LETÍCIA PASSOS. O trabalho em emergência hospitalar: sofrimento e estratégias defensivas dos enfermeiros. Revista Gaúcha de Enfermagem, 2018; 39: e2017-0255.

FANG, Ya Xuan. Burnout and work-family conflict among nurses during the preparation for reevaluation of a grade a tertiary hospital. Chinese Nursing Research, 2017.4(1), 51-55.

GARBIN, Keiti et al. A Idade como Diferencial no Engagement dos Profissionais de Enfermagem. Psic.: Teor. e Pesq., Brasília , v. 35 e35516, 2019 . Available from 37722019000100615&lng=en&nrm=iso>.

LACCORT, Alessandra de Almeida; DE OLIVEIRA, Grasilela Backer. A importância do trabalho em equipe no contexto da enfermagem. Revista Uningá REVIEW, [S.l.], v. 29, n. 3, mar. 2017. ISSN 2178-2571.

MACHADO, Maria Helena et al. Mercado de trabalho em enfermagem no âmbito do SUS: uma abordagem a partir da pesquisa Perfil da Enfermagem no Brasil. Divulgação Saúde Debate, 2016.56: 52-69.

OLIVEIRA, Bruno Luciano Carneiro Alves de; SILVA, Alécia Maria da; LIMA, Sara Fiterman. Carga Semanal de Trabalho Para Enfermeiros no Brasil: Desafios para o exercício da profissão. Trab. educ. saúde, Rio de Janeiro, v. 16, n. 3,p. 1221-1236, Dec. 2018

OLIVEIRA, Lucia Barbosa de; ROCHA, Juliana da Costa. Engajamento no trabalho: antecedentes individuais e situacionais e sua relação com a intenção de rotatividade. Rev. bras. gest. Neg., São Paulo, v. 19, n. 65p. 415-431, Sept. 2017 .

ROTTA, Daniela Salgagni et al., Engagement of multi-professional residents in health. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2019;53:e03437.

SANTOS, José Luiz Guedes et al., Ambiente de Trabalho do Enfermeiro na Divisão de Enfermagem Materno-Infantil de um Hospital Universitário. Revista de Enfermagem do Centro-Oeste Mineiro. 2018;8: e 2099. doi: https://doi.org/10.19175/recom.v7i0.2099

SANTOS, Luciana Soares Costa; GUIRARDELLO, Edinêis de Brito. Demandas de atenção do enfermeiro no ambiente de trabalho. Revista Latino-americana de Enfermagem, 2007. janeiro-fevereiro; 15(1).

SCHAUFELI, Wilmar. Applying the Job Demands-Resources model: A How to guide measuring and tackling work engagement and burnout. Organizational Dynamics, 2017.46 (2).120-127.

SCHAUFELI, Wilmar; SALANOVA, Maria; GONZALEZ-ROMÁ Vicent, BAKKER, Arnold. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness studies, 2002; 3(1), 71-92.

SILVA, Rômulo Botelho et al., Qualidade da assistência de enfermagem em unidade de terapia intensiva de um hospital escola. Revista Gaúcha de Enfermagem, 2013;34(4):114-120.

VAZQUEZ, Ana Claudia Souza et al. Evidências de validade da versão brasileira da escala de workaholism (DUWAS-16) e sua versão breve (DUWAS-10). Avaliação psicológica, Itatiba, v. 17,n. 1,p. 69-78, 2018 .

VIANA, Renata Andrea Pietro Pereira et al. Perfil do enfermeiro de terapia intensiva em diferentes regiões do Brasil. Texto contexto – enferm., Florianópolis , v. 23,n. 1,p. 151-159, Mar. 2014 .

ZEIJEN, Marijntje; PEETERS Maria & HAKANEN, Jari. Workaholism versus work engagement and job crafting: What is the role of self-management strategies? Human Resource Management Journal; 2018, 28:357–373. doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.

[1] Master’s degree in Social Psychology from Salgado de Oliveira University; Master in Intensive Care by Ibrati; Specialist in Medical Nursing – Intensive; Specialist in oncology nursing; graduated in Nursing.

[2] Guidance counselor. PhD in Psychology.

Submitted: November, 2020.

Approved: December, 2020.