ORIGINAL ARTICLE

FACCO, Lucas [1], MADEIRA, Laura Wanessa [2], FECURY, Amanda Alves [3], ARAÚJO, Maria Helena Mendonça de [4], OLIVEIRA, Euzébio de [5], DENDASCK, Carla Viana [6], SOUZA, Keulle Oliveira da [7], DIAS, Claudio Alberto Gellis de Mattos [8]

FACCO, Lucas. Et al. Confirmed cases of dengue in Brazil between the years 2008 to 2012. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 05, Ed. 12, Vol. 10, pp. 17-27. December 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/health/dengue-in-brazil, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/health/dengue-in-brazil

SUMMARY

Dengue is caused by an RNA virus, which has 4 identified variations present in the human environment. Its main symptomatological manifestations include fever, muscle pain (myalgia), retro ocular pain, joint pain (arthralgia), headache (headache), nausea, vomiting and others, such as rash. This article aims to show the number of confirmed dengue cases in Brazil between 2008 and 2012. In Brazil, dengue is characterized as a major public health problem, being one of the diseases of an infectious nature that is very present. Some factors, such as the climate (predominantly tropical), deficient infrastructure of the urban environment, in addition to demographic expansion, which occurs in a disorderly manner, can provoke and possibly justify this national scenario. It represents a major public health problem, since the control of the disease depends on the fight against its vector, which spreads very easily in the country, due to climatic and anthropic factors. For the disease to be tackled efficiently in the country, the most effective method is to combat the vector. Garbage and materials must be efficiently separated and stored in suitable locations for further recycling, so that they do not accumulate water and become mosquito breeding sites.

Keywords: Dengue, Aedes aegypti, Epidemiology.

INTRODUCTION

Dengue is a febrile pathology caused by an arbovirus, which is part of the Flaviridae family (MASERA et al., 2011). Human infection by this virus (RNA virus) occurs through the bite of the female hematophagous mosquito called Aedes aegypti. This virus has 4 identified variations, which are: DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3 and DENV-4, and the potential for virus infection in one person is only once for each of these types, because the body develops specific immunity for each serotype (XAVIER et al., 2014). In addition to these 4 variations, in 2013 the fifth dengue serotype (DENV-5) was isolated, but it has a wild cycle, unlike the other ones (MUSTAFA et al., 2014). The disease has different clinical forms, such as Classic Dengue, Dengue with Complications, Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever, and if it evolves to its most severe form, Dengue Shock Syndrome (DIAS et al., 2010).

The main manifestations related to dengue are fever (usually high and with sudden onset), severe muscle pain (myalgia), retroocular pain, joint pain (arthralgia), headache (headache), nausea, vomiting and other symptoms, such as rash, the latter being more common in infections that occur primarily, and hemorrhages in a rarer way and may bring risk of death to the patient (DIAS et al. , 2010).

In Brazil, although there are campaigns to control the disease vector, they do not occur with the necessary efficacy, since the growth in the number of dengue cases and deaths from the disease increased strongly between the period 2000 to 2015 (ARAÚJO et al., 2017).

Patients with suspected dengue can be stratified into four different groups by flowchart of the Ministry of Health (groups A, B, C and D), based on the presence or not of some sign of severity. Patients generally need to start hydration after dengue is suspected, and groups A and B receive oral hydration, while groups C and D receive intravenous hydration (BRASIL, 2016).

For dengue prevention and control to occur efficiently, it is necessary to combat the vector assiduously, and living environments must be constantly cleaned, in order to avoid the presence of objects that can be breeding for the mosquito, as they accumulate water. Insecticides are also useful for the control and prevention of the disease, since they are able to eliminate the vector, both in its adult and immature form. (FURTADO et al., 2019).

In Brazil, in 2012, 576,758 cases of dengue (through the gender variable) were reported, and 44% of this value (255,069 cases) corresponded to males, while the remaining 56% (321,386 cases) were female. In the same period, the state of Rio de Janeiro had the highest number of notifications (177,798 cases), representing approximately 30% of all national cases reported during the analyzed period (SILVA et al., 2014).

GOALS

This article aims to show the number of confirmed dengue cases in Brazil between 2008 and 2012.

METHOD

Results obtained on the DATASUS (http://datasus.saude.gov.br) website. First, the “access to information” tab was clicked, then the option” “health information (TABNET)” was selected, then clicked on “epidemiological and morbidity”. On the following page, we selected “Diseases and Diseases of Notifiable – From 2007 onwards (SINAM)”. On the next page, the “Dengue” option was selected. In the tab “geographical coverage” the option “Brazil by Region, UF and Municipality” was selected. To obtain the data, the following options were selected in the line field: “Year 1st symptoms”, “age group”, “Notification region”, “gender”, “evolution of notification”, “notifications by pregnant women”, “zone of residence”, “notification by schooling” and “notification by class. end.” For all of the above options, the “not active” option was selected in the column field; in the “content” field, the “confirmed cases” option; and in available data periods from 2008 to 2012.The data charts were made within the Excel application, a component of the Microsoft Corporation Office suite. The bibliographic research was carried out in scientific articles, using computers from the computer laboratory of the Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Amapá, Macapá Campus, located at: Rodovia BR 210 KM 3, s/n – Bairro Brasil Novo. ZIP Code: 68.909-398, Macapá, Amapá, Brazil.

RESULTS

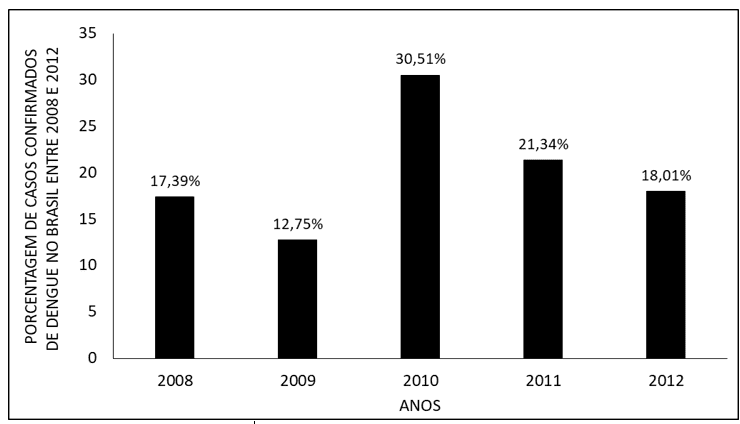

Figure 1 shows the percentage of confirmed dengue cases in Brazil between 2008 and 2012, per year. The highest percentage occurred in 2010 (30.51%), followed by 2011 (21.34%), 2012 (18.01%), 2008 (17.39%) and finally, 2009 (12.75%).

Figure 1 – Shows the percentage of confirmed dengue cases in Brazil between 2008 and 2012, per year.

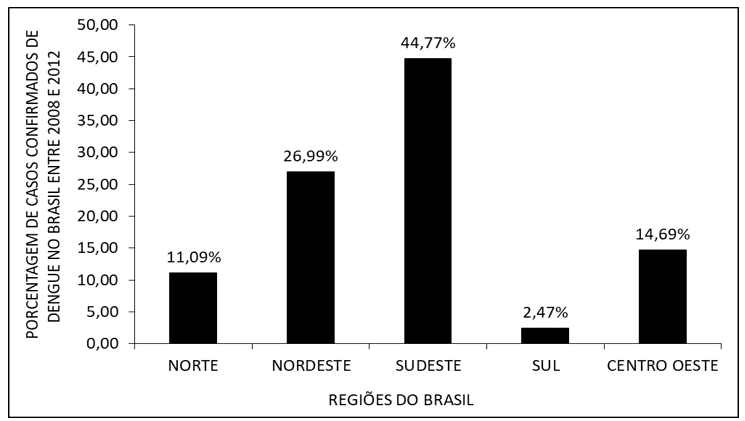

Figure 2 shows the percentage of confirmed dengue cases in Brazil between 2008 and 2012, by regions of the country. In the study period, the Southeast region presented the highest percentage of cases (44.77%), followed by the Northeast (26.99%), Midwest (14.69%), North (11.09%) and South (2.47%).

Figure 2 – Shows the percentage of confirmed dengue cases in Brazil between 2008 and 2012, by regions of the country.

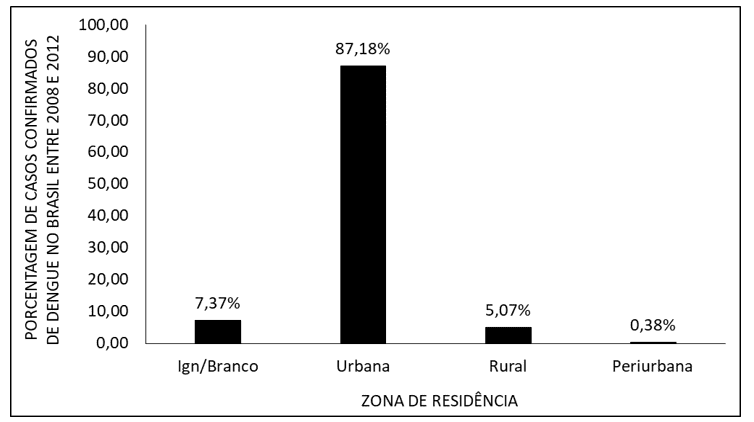

Figure 3 shows the percentage of confirmed dengue cases in Brazil between 2008 and 2012, per area of residence. The urban area presented a large percentage of cases (87.18%), and the percentage of the rural area was significantly lower (5.07%). In addition, 0.38% of the cases occurred in the periurban region and 7.37% were not determined.

Figure 3 – Shows the percentage of confirmed dengue cases in Brazil between 2008 and 2012, by area of residence.

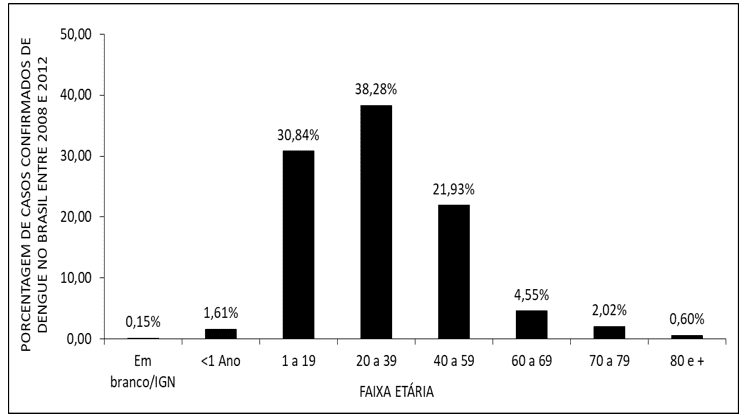

Figure 4 shows the percentage of confirmed dengue cases in Brazil between 2008 and 2012, by age group. It is noted that, during the period studied, the age group with the highest percentage of cases was 20 to 39 years (38.28%), followed by 1 to 19 (30.84%), 40 to 59 (21.93%), 60 to 69 (4.55%), 70 to 79 years (2.02%), <1 ano (1,61%) e 80 ou mais (0,60%). In addition, 0.15% of the cases did not have their age group determined.

Figure 4 – Shows the percentage of confirmed dengue cases in Brazil between 2008 and 2012, by age group.

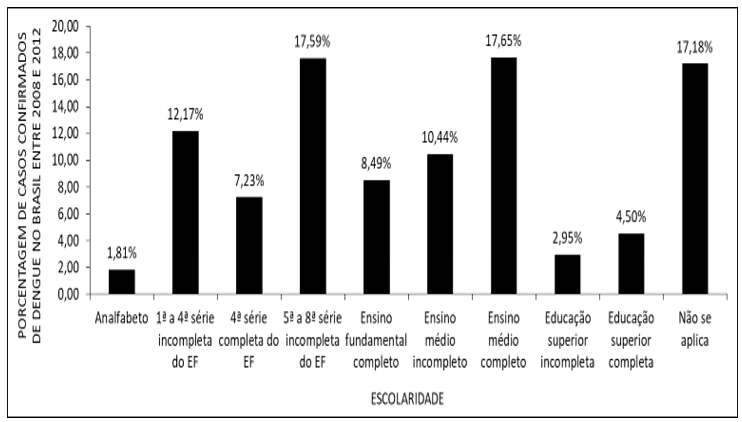

Figure 5 shows the percentage of confirmed dengue cases in Brazil between the years 2008 to 2012, according to education. The highest value of cases occurred in the education category Complete High School (17.65%), followed by 5th to 8th grade of incomplete Elementary Education (EF) (17.59%), 1st to 4th grade of incomplete EF (12.17%), Incomplete High School (10.44%), Completed Elementary School (8.49%), Incomplete 4th Grade of EF (7.23%), Completed Higher Education (4.50%) , Incomplete higher education (2.95%) and illiterate (1.81%). 17.18% of the total fell into the “Not applicable” category.

Figure 5 – Shows the percentage of confirmed dengue cases in Brazil between 2008 and 2012, by schooling.

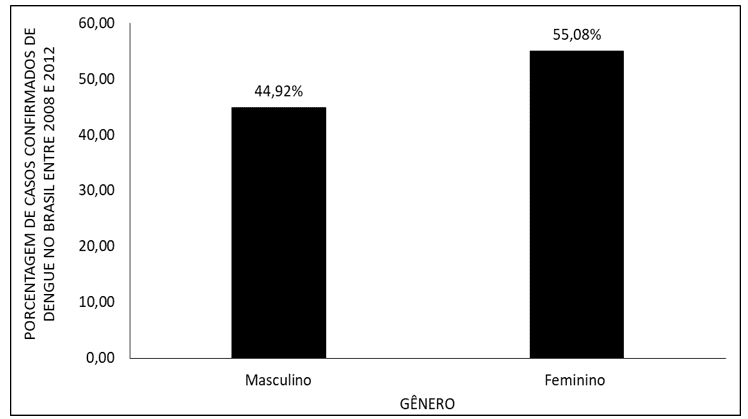

Figure 6 shows the percentage of confirmed dengue cases in Brazil between 2008 and 2012, by gender. It is noted that the percentage of confirmed cases during the period under analysis was higher among females (55.08%), while males represented 44.92% of the cases.

Figure 6 – Shows the percentage of confirmed dengue cases in Brazil between 2008 and 2012, by gender.

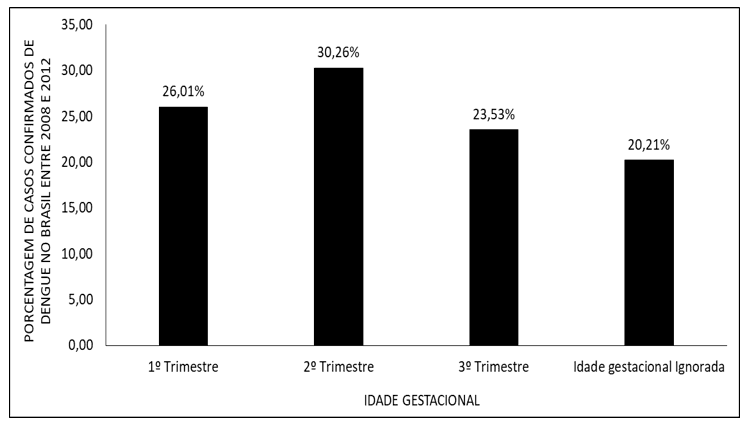

Figure 7 shows the percentage of confirmed dengue cases in Brazil between 2008 and 2012, by gestational age. 30.26% of the cases corresponded to the 2nd trimester of gestational age, followed by the 1st trimester (26.01%) and 3rd quarter (23.53%). 20.21% of the cases had their gestational age ignored.

Figure 7 – Shows the percentage of confirmed dengue cases in Brazil between 2008 and 2012, by gestational age.

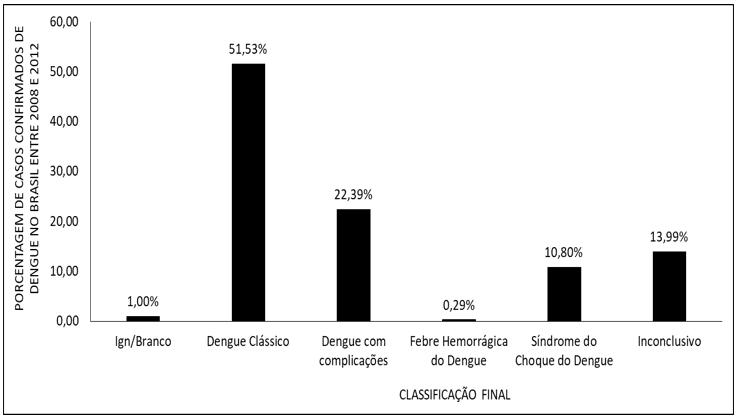

Figure 8 shows the percentage of confirmed dengue cases in Brazil between 2008 and 2012, according to the final classification of cases. A widely higher value was observed for Classic Dengue (51.33%), followed by Dengue with complications (22.39%), Inconclusive (13.99%), Dengue Shock Syndrome (10.80%) dengue hemorrhagic fever (0.29%). 1.00% of cases were not specified (Ign/Branco).

Figure 8 – Shows the percentage of confirmed dengue cases in Brazil between 2008 and 2012, according to the final classification of cases.

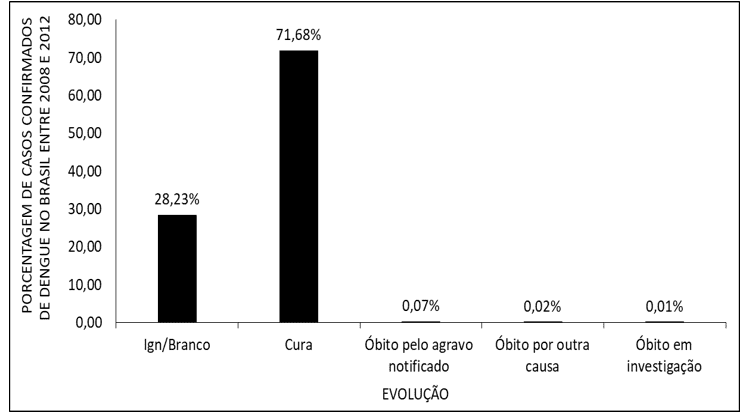

Figure 9 shows the percentage of confirmed dengue cases in Brazil between 2008 and 2012, due to the evolution of the cases. A large majority of cases evolved with Cure (71.68%), followed by 0.07% of Deaths from reported injury, 0.02% from Deaths from another cause and 0.01% from Deaths under investigation. 28.23% of the cases were not specified (Ign/Branco).

Figure 9 – Shows the percentage of confirmed dengue cases in Brazil between 2008 and 2012, due to the evolution of the cases.

DISCUSSION

In Brazil, dengue is characterized as a major public health problem, being one of the diseases of an infectious nature that is very present. Some factors, such as climate (predominantly tropical), deficient infrastructure of the urban environment, in addition to demographic expansion, which occurs in a disorderly manner (COSTA e CALADO, 2016), can provoke and possibly justify this national scenario, characterizing the aggravation in the number of cases between the period 2009 to 2010, and the highest percentage of notifications, in view of the period studied , takes place in 2010.

Among the Brazilian geographic regions, the one with the highest number of dengue cases is the Southeast, and the state with the highest percentage value of cases is Rio de Janeiro, and this, in 2012, represented about 30% of the national cases. The Southeast region is the region with the highest degree of urbanization, and Rio de Janeiro presents visible disorder in its urban growth, since it is noted the expansion of favelas and, concomitantly, socio-spatial segregation, factors that trigger the inequality and difficulty of local living, since very precarious sanitation conditions favor the proliferation of the Mosquito Aedes Aegypti, vector of dengue (SILVA et al., 2014).

The vast majority of dengue cases occur in the urban region, and in the study period, it represented almost 90% of the total cases. The urban region has constant growth and development, however, it does not always occur adequately, favoring the increase of breeding sites for the vector. One of the factors that may explain this increase would be the inefficient collection of garbage, since not all localities are contemplated in the same way and, thus, especially disposable materials, can favor the accumulation of water and generate an environment conducive to mosquito proliferation. In addition, the residences located in urban centers are very close, so if there are vector outbreaks in a house, neighboring dwellings will also be subject to dengue, providing even greater ease for mosquito dispersion in various environments (HORTA et al., 2013).

The age group whose percentage of notifications was more comprehensive is 20 to 39 years, a characteristic that is corroborated in other studies, denoting the increase in the incidence of cases through increasing age, and this increase stabilizes in the age group between 30 and 39 years, decreasing significantly from it (RIBEIRO et al. , 2006). In addition, it is noted that the highest incidence occurs in patients whose schooling presented refers to complete high school, a factor supported by other epidemiological studies that show that patients had 6 to 9 years of schooling, as well as patients with 10 or more years of schooling, showed a greater amount of antibodies to dengue, i.e., i.e. , were affected by the pathology (TAVARES, 2014).

The largest number of reported cases covers females, representing approximately 55% of the total within the study period. One of the possible factors that may explain such data is the longer period of time they are in their homes, since the home environment is the place where dengue transmission occurs the most (SILVA et al., 2014)

In the period in question (2008 to 2012), the highest number of notifications occurred in pregnant women in the second trimester of pregnancy. Pregnant women may also contract dengue, and should be constantly monitored in these cases, since dengue during pregnancy can cause problems in gestational evolution, such as the occurrence of hemorrhages, eclampsia and preeclampsia. Among these, hemorrhage tied to thrombocytopenia, in addition to acute infections and damage to the placenta in the first trimester of pregnancy, represent the main causes of death in pregnant women with dengue. Thus, it is observed that pregnant women are characterized as a group that presents marked vulnerability to dengue, both in relation to the evolution of the disease with complications, as well as the possibility of maternal death due to this pathology. It should be emphasized, however, that although there may be such complications during pregnancy, dengue is not usually related to congenital malformations (NASCIMENTO et al., 2017).

Dengue presents different clinical forms, such as Classic Dengue, dengue with Complications, Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever, and if the patient evolves negatively, it may present in its most severe form, then dengue shock syndrome occurs. Among them, the most prevalent is the classic one, and the patient usually presents sudden high fever, headaches (headaches), muscle pain (myalgia), joint pain (arthralgia), weakness and other symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, rash (which occur mainly in primary infections and orbital pain. In addition, even in the classical form of the disease, patients may present hemorrhages, which may occur spontaneously, such as nasal bleeding (epistaxis), gingivals, and the appearance of petechiae, or provoked (by performing the loop test, if positive) (DIAS et al., 2010).

The most severe form of dengue is called Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever, or simply hemorrhagic dengue, and, if not managed efficiently and agilely, it can evolve to Dengue Shock Syndrome, characterized by the shock of the patient’s circulatory system, which can quickly lead to death. Certain signs are considered as “alarm” for the team responsible for patient care (postural and arterial hypotension, hemorrhages, constant vomiting, decreased diuresis, increased hematocrit and among others, such as decreased diuresis), through such signs, following the guidelines of the Ministry of Health, patients can be divided into 4 groups (A, B, C and D), from cases minor to major complication , in order to guide the therapeutic approach, and groups A and B show no signs of severity, while groups C and D present such signs (DIAS et al., 2010 e BRASIL, 2016).

CONCLUSION

Dengue is a pathology transmitted by the Aedes Aegypti mosquito, having four serotypes that are part of the human cycle (DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, DENV-4). In Brazil, it represents a major public health problem, since the control of the disease depends on the fight against its vector, which spreads very easily in the country, due to climatic and anthropic factors, such as disordered urbanization and the consequent sanitary problem of accumulation of garbage and disposable objects in public and even residential environments , facilitating the proliferation of mosquito breeding sites and their consequent multiplication.

It is noted that the region most affected by dengue is the Southeast, in view of the scope of its urban area, and the state with the highest rate of notifications is Rio de Janeiro, in view of the broad process of socio-spatial segregation that occurs there, with a large coverage of slums and lack of infrastructure and basic sanitation , resulting in a high amount of vector breeding sites.

Having four main clinical presentations (Classic Dengue, Dengue with Complications, Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever and Dengue Shock Syndrome), the most prevalent of all is Classic Dengue, in which patients do not usually show signs of severity. Depending on the patient’s symptomatological presentation, according to the Ministry of Health, it should be classified among four groups (A, B, C and D), and its therapeutic regimen will derive from such classification. The patient should receive hydration and be properly managed, so that it does not evolve negatively and thus avoid the most complicated form of the disease.

Pregnant women present themselves as a vulnerable group for dengue, and the disease may, depending on the trimester of pregnancy, generate different negative consequences for the mother’s health, in order to endanger her life. Dengue is not classified as causing congenital malformations.

For the disease to be tackled efficiently in the country, the most effective method is to combat the vector. Garbage and materials must be efficiently separated and stored in suitable locations for further recycling, so that they do not accumulate water and become mosquito breeding sites.

REFERENCES

ARAÚJO, V. E. M.; BEZERRA, J. M. T.; AMÂNCIO, F. F.; PASSOS, V. M. A.; CARNEIRO, M. Aumento da carga de dengue no Brasil e unidades federadas, 2000 e 2015: análise do Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Rev Bras Epidemiol, suppl 1, p. 205-216, 2017.

BRASIL. Dengue: diagnóstico e manejo clínico: adulto e criança. Brasilia DF: Ministério da Saúde. 58 p. 2016. Disponível em: <https://portalarquivos2.saude.gov.br/images/pdf/2016/janeiro/14/dengue-manejo-adulto-crianca-5d.pdf>. Acesso em: 13 Dezembro 2020.

COSTA, I. M. P.; CALADO, D. C. Incidência dos casos de dengue (2007-2013) e distribuição sazonal de culicídeos (2012-2013) em Barreiras, Bahia. Epidemiol Serv Saude, v. 25. N. 4, p. 735-744, 2016.

DIAS, L. B. A.; ALMEIDA, S. C. L.; HAES, T. M.; MOTA, L. M.; RORIZ-FILHO, J. S. Dengue: transmissão, aspectos clínicos, diagnóstico e tratamento. Medicina (Ribeirão Preto), v. 43, n. 2, p. 142-152, 2010.

FURTADO, A. N. R.; LIMA, A. S. F.; OLIVEIRA, A. S.; TEIXEIRA, A. B.; FERREIRA, D. S.; OLIVEIRA, E. C.; CAVALCANTI, G. B.; SOUSA, W. A.; LIMA, W. M. Dengue e seus avanços. RBAC, v. 52, n. 3, p. 196-201, 2019.

HORTA, M. A. P.; FERREIRA, A. P.; OLIVEIRA, R. B.; WERMELINGER, E. D.; KER, F. T. O.; FERREIRA, A. C. N.; CATITA, C. M. S. Os efeitos do crescimento urbano sobre a dengue. Revista Brasileira em Promoção da Saúde, v. 26, n. 4, p. 539-549, 2013.

MASERA, D. C.; SCHENKEL, G. C.; SILVA, L. L.; SPANHOL, M. R.; FRACASSO, R.; BONOTTO, R. M.; LARA, G. M. Febre Hemorrágica da Dengue: Aspectos Clínicos, Epidemiológicos e Laboratoriais de uma Arbovirose. Revista Conhecimento Online, v. 2, p. 1-22, 2011.

MUSTAFA, M. S.; RASOTGI, V.; JAIN, S.; GUPTA, V. Discovery of fifth serotype of dengue vírus (DENV-5): A new public health dilema in dengue control. Medical Journal Armed Forces India, v. 71, n. 1, p. 67-70, 2015.

NASCIMENTO, L. B.; SIQUEIRA, C. M.; COELHO, G. E.; SIQUEIRA JÚNIOR, J. B. Dengue em gestantes: caracterização dos casos no Brasil, 2007-2015. Epidemiol Serv Saude, v. 26, n. 3, p. 433-442, 2017.

RIBEIRO, A. F.; MARQUES, G. R. A. M.; VOLTOLINI, J. C.; CONDINO, M. L. F. Associação entre incidência de dengue e variáveis climáticas. Rev Saúde Pública, v. 40, n. 4, p. 671-676, 2006.

SILVA, E. M.; JESUS, S. R. R.; FONSECA, I. S. S. Epidemiologia da Dengue no Brasil no ano de 2012. Ciências Biológicas e da Saúde, v. 2, n. 2, p. 69-78, 2014.

TAVARES, A. S. Prevalência e Incidência de Infecção pelo Vírus da Dengue em uma Comunidade Urbana: Um Estudo de Coorte. Dissertação (Mestrado em Biotecnologia em Saúde e Medicina Investigativa) – Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Bahia, Salvador, 2014.

XAVIER, A. R.; FREITAS, M. S.; LOUREIRO, F. M.; BORGHI, D. P.; KANAAN, S. Manifestações clínicas na dengue, Diagnóstico Laboratorial. JBM, v. 102, n. 2, p. 7-14, 2014.

[1] Student of the Medical Course of the Federal University of Amapá (UNIFAP).

[2] Mining Technique, as a result of the Federal Institute of Amapá (IFAP).

[3] Biomedical, PhD in Tropical Diseases, Professor and researcher in the Medicine Course at the Federal University of Amapá (UNIFAP).

[4] Physician, Professor and researcher of the Medical Course of the Federal University of Amapá (UNIFAP).

[5] Biologist, PhD in Tropical Diseases, Professor and researcher at the Physical Education Course at the Federal University of Pará (UFPA).

[6] Theologian, PhD in Psychoanalysis, researcher at the Center for Research and Advanced Studies – CEPA.

[7] Sociologist, Master’s student in Anthropic Studies in the Amazon, Member of the Research Group “Laboratory of Education, Environment and Health” (LEMAS/UFPA).

[8] Biologist, PhD in Theory and Behavior Research, Professor and researcher of the Graduate Program in Professional and Technological Education (PROFEPT), Federal Institute of Amapá (IFAP).

Submitted: December, 2020.

Approved: December, 2020.