SILVA, Fábio Tenório [1], ARAÚJO, Franciolli da Silva Dantas [2], FECURY, Amanda Alves [3], OLIVEIRA, Euzébio [4], DENDASCK, Carla Viana [5], DIAS, Claudio Alberto Gellis de Mattos [6]

SILVA, Fábio Tenório. Et al. Global and national tin overview between 2010 and 2014. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 03, Ed. 09, Vol. 08, pp. 12-21 September 2018. ISSN:2448-0959

SUMMARY

Brazilian tin production on an industrial scale began in the 1940s and expanded in 1950. However, internal importance only happened with the discovery of the cassiterite deposit of Rondônia in 1950. Despite this, Brazil was not part of the International Tin Counciul (ITC) which was the market agreement of the majority countries in the production of tin at the time and this became an obstacle to the valorization of tin in international trade. Metallic tin is employed in coating for steel containers, in the production of welding for joints of pipes or electrical circuits, in ceramics, in the manufacture of glass, in the production of brass and in its secondary form, scrap, it is used in the production of tin. The aim of this article is to show the global and national tin panorama between 2010 and 2014. The data to perform this article were taken from the National Department of Mineral Production – DNPM (http://www.dnpm.gov.br/). The bibliographic research was carried out in scientific articles found in the worldwide computer network. Tin went through a relatively positive period between the years surveyed. It was found that the world production of tin had few changes; whereas Asia is the main continent holding tin reserves; that the Brazilian production of metallic and contained tin increased during the analyzed period; that Brazil exports more than imports tin; that the apparent consumption varied, closing on a high; and that the price of the ton was very close during the years surveyed. The crises in the international market have failed to affect production so strongly that it increased from investments in the extraction of raw materials.

Keywords: Tin, Market, Stability, Internal Consumption.

INTRODUCTION

Tin is a chemical element mainly taken from cassiterite, a mineral-ore whose composition is tin dioxide (Sn02) (RAMOS, 2003). Most tin is used in protective coating or as alloy if it is associated with other metals (USGS, 2017). The metallic tin is extracted from cassiterite from chemical reactions that remove oxides from the mineral, leaving only the chemical element of interest (BROCCHI, 2017).

Mining is an economic activity aimed at the extraction and processing of ores found in rocks and/or soil. Currently it is expensive and complex, because in-depth studies are needed to determine the location of the ore, size of mineral reserves, safety, feasibility and economic viability for activities to be started (GANEM et al., 2016)

Minerals are formed simultaneously in the soil and when they have economic value, they are called ore. To market a given mineral it is necessary to remove it from the ore in which it is contained and this is done from concentration processes, where industrial procedures such as sieving and comminution separatthe mineral of interest to obtain it, if possible, in metallic form. The procedures to obtain the metal of a mineral are chemical and they from electrochemical reactions, reactions at high temperatures or in dissolution of aqueous substances. In the case of tin, the metal is normally obtained from the removal of the oxide present in the chemical composition of cassiterite. The equipment that promotes the reaction needs to present a temperature higher than the melting point of the tin to generate the metal in liquid state. The liquid undergoes the steps of refinement and compositional adjustment to be sold (BROCCHI, 2017).

Cassiterite deposits are usually formed in igneous rocks such as riolites or granites, for example. However, the formation of the deposit of this mineral can also occur in places deposits from the erosion of igneous rocks, as occurs when it is related to tungsten, for example. The rocks that contain cassiterite and that were formed at high temperatures are weathered by the action of water, oxidizing. Because it is a non-ferrous mineral-ore, cassiterite remains intact and is transported by processes of natural mechanical concentration, forming deposits in rivers. From this, cassiterite deposits acquire several geological environments favorable for their formation (RODRIGUES, 2001; RAMOS, 2003).

The tin is a malleable silver metal. Its density varies between 6.8 g/cm³ and 7.1 g/cm³ and below 13.2°C it becomes white or gray. It is mainly taken from cassiterite, a mineral-ore whose chemical composition is tin dioxide (Sn02). Cassiterite is usually found in igneous rocks, such as granites and riolites, for example. Therefore, its formation is in media with very high temperatures (RAMOS, 2003; DNPM, 2017a).

The metallic tin is used in coating for steel containers, in the production of welding for joints of pipes or electrical circuits, in ceramics, in the manufacture of glass, in the production of brass and in its secondary form, scrap, it is used in the production of tin (DNPM, 2017; USGS, 2017; DNPM, 2017a).

Brazilian tin production on an industrial scale began in the 1940s and expanded in 1950. However, internal importance only happened with the discovery of the cassiterite deposit of Rondônia in 1950. Despite this, Brazil was not part of the International Tin Counciul (ITC) which was the market agreement of the majority countries in the production of tin at the time and this became an obstacle to the valorization of tin in international trade. In the 1970s, Brazilian tin gained strength with the application of government sources for mineral research and metallurgical production (CUTER and KON, 2008). World tin production in 2014 was 286,000 t. In the same year, Brazilian production was equivalent to 14,700 t (USGS, 2016).

Import is the term given to the entry of products or services in a country with foreign origin and may or may not have economic value (Brazil, 2014). Brazil imported 669 t of tin in 1999, the largest amount of the mineral imported from the end of the 1980s to the year 2000. In the same year the value of tin was at its peak in the foreign market, US$ FOB 3,800 10³ (BROCCHI, 2017).

Export is the evasion of products or services of a particular homeland, whether they originate or come from it and they may have value or not (BRASIL, 2015). In 1989, Brazilian tin obtained its highest export data between 1988 and 2000 with 34,166 t, costing US$ FOB 286,081 10³, also its highest value in this period. The main destinations of the raw material were the United States, Argentina and Chile (BROCCHI, 2017).

The Brazilian export and import of tin is usually carried out from the value of ton (t) in dollars per FOB. Free on Board (FOB) is an acronym regulated by the National Chamber of Commerce (CCN) that is used when the carrier has the responsibility of the product until it is in the vessel of its transport (IPEA, 2010).

In 2014, tin was worth 994 cents per pound, according to the London Metal Exchange (LME) and evaluating its prices between 2010 and 2011, it was noted that in 2011 it had its highest market value at 1,188 cents per pound (USGS, 2016).

Goal

Present the global and national tin panorama between 2010 and 2014.

Method

The data were taken from the National Department of Mineral Production – DNPM (http://www.dnpm.gov.br/). On the home page, in the topic "Collection", the "Publications" tab was selected. Clicked on the "Statistics and Mineral Economy" option icon. The "Mineral Summary" icon has been selected on the new page that opened. The summaries from 2010 to 2014 were downloaded in PDF and data on tin were collected from the tables "Reserves and world production" and "Main statistics – Brazil". The data was compiled within the Excel application, a component of the Microsoft Corporation Office suite. The bibliographic research was carried out in scientific articles found in the worldwide computer network, made in machines of the computer laboratory of the Federal Institute of Education, Science and Technology of Amapá, Macapá Campus, located at Highway BR 210 KM 3, s/n – Bairro Brasil Novo. ZIP Code: 68.909-398, Macapá, Amapá, Brazil.

Results

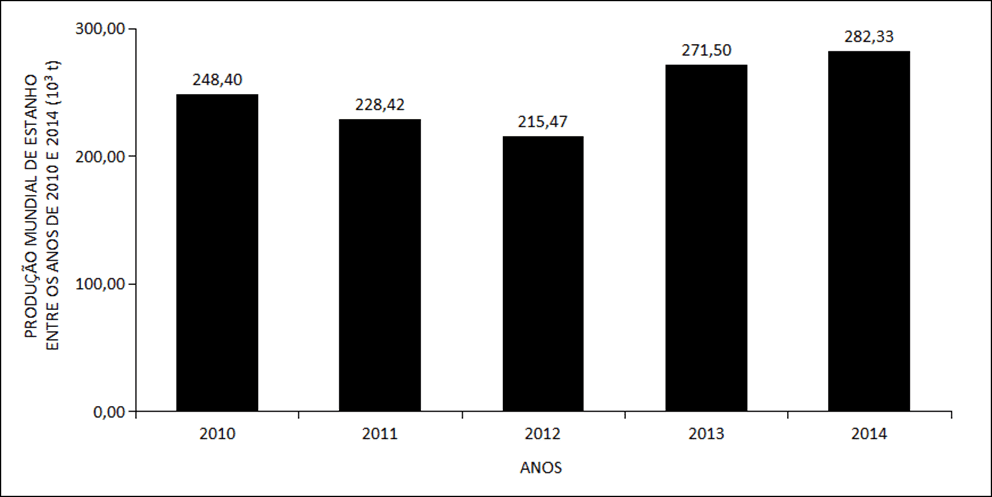

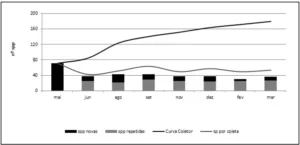

Figure 1 shows the world production of tin between 2010 and 2014. Data show that production decreased in 2011 and 2012 and that it increased in the last two years surveyed.

Figure 1: World tin production between 2010 and 2014.

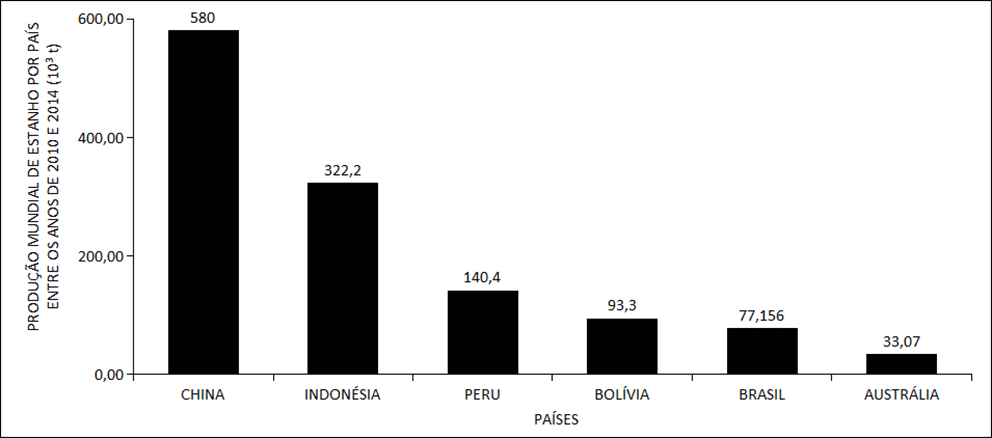

Figure 2 shows data on world tin production by country between 2010 and 2014. The data shows that China and Indonesia are the largest producers of tin and that Australia is the smallest producer during the research period.

Figure 2: World tin production by country between 2010 and 2014.

Figure 3 shows the production of tin in Brazil in metallic form between 2010 and 2014. Data show that the production of metallic tin increased in Brazil from 2011 to 2014.

Figure 3: Production of tin in Brazil in metallic form between 2010 and 2014.

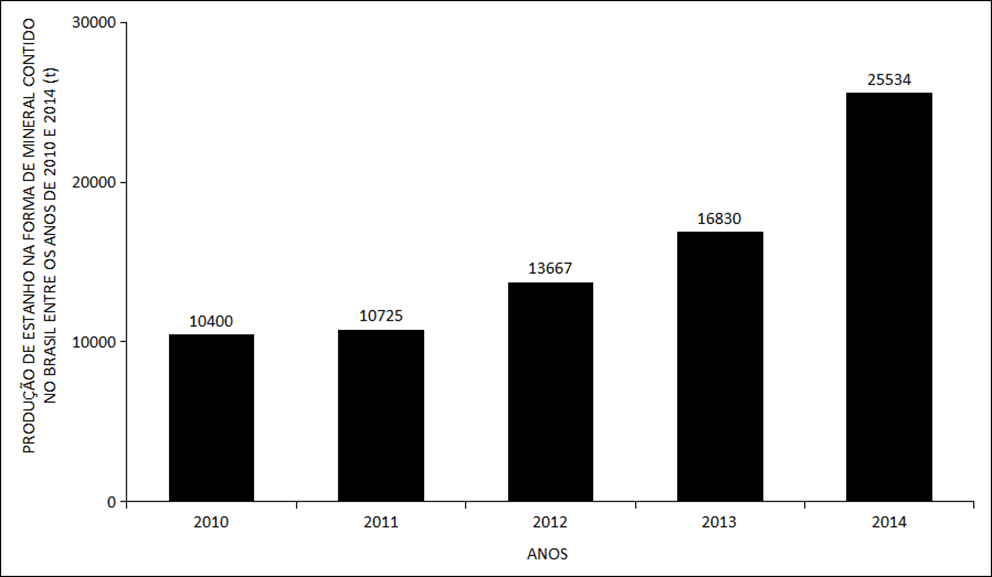

Figure 4 shows the production of tin in Brazil in the form of mineral contained between 2010 and 2014. The data show that the production of contained tin increased in Brazil between the years of the research.

Figure 4: Tin production in Brazil in the form of mineral contained between 2010 and 2014.

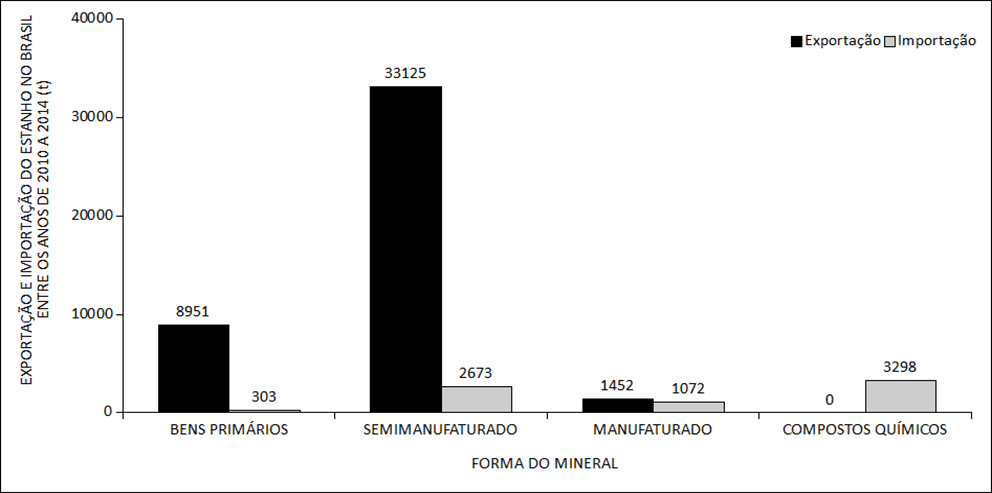

Figure 5 shows data on imports and exports of tin in Brazil between 2010 and 2014. The data show that Brazil exported more than imported tin, except in chemical compound, where there was no tin export in Brazil during the period surveyed.

Figure 5: Export and import of tin in Brazil between 2010 and 2014.

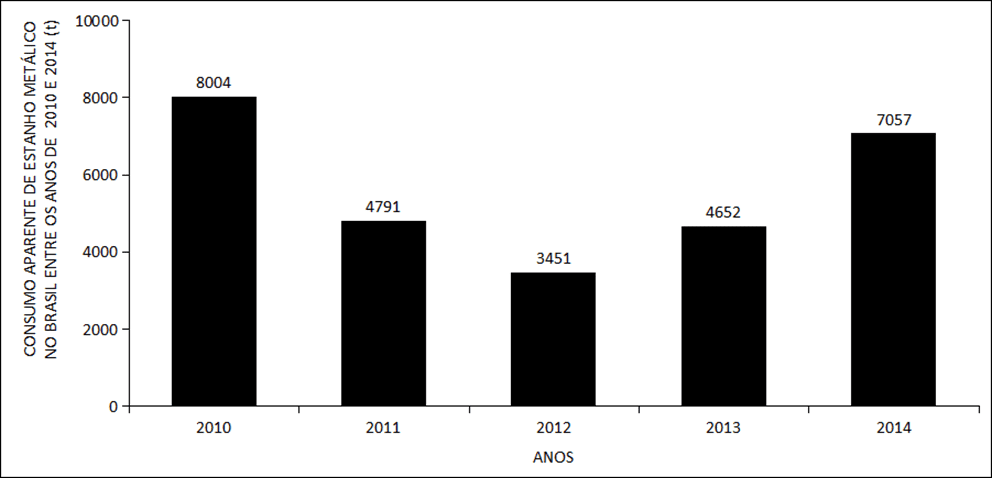

Figure 6 shows the apparent consumption of metallic tin in Brazil between 2010 and 2014. Data show that apparent consumption decreased in 2011 and 2012 and increased in the last two years of the survey.

Figure 6: Apparent consumption of metallic tin in Brazil between 2010 and 2014.

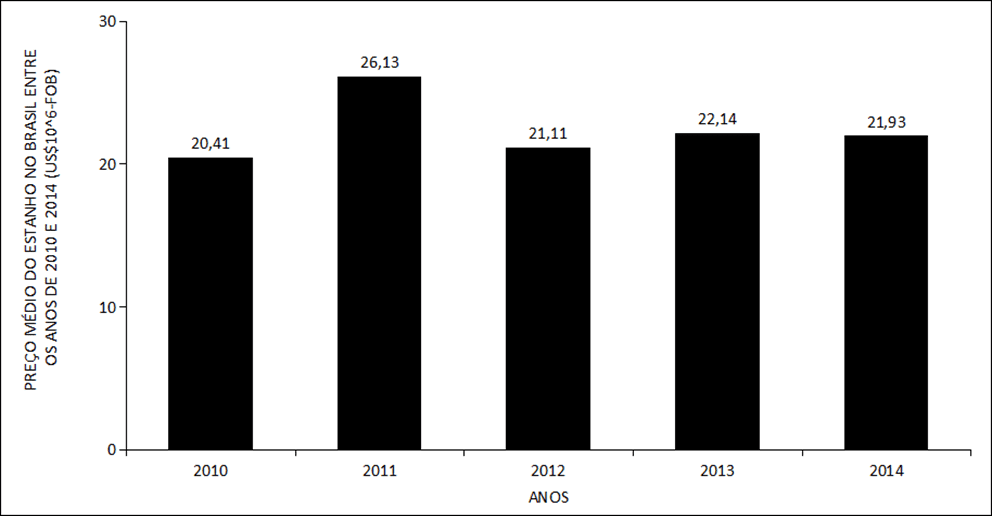

Figure 7 shows the average price of tin in Brazil, in dollars, between 2010 and 2014. According to the chart the tin had higher value in 2011 in Brazil and it had the cheapest price  in 2010

in 2010

Figure 7: Average tin price in Brazil between 2010 and 2014.

Discussion

Several countries have signed strategic partnerships and built projects between 2009 and 2011 to expand domestic tin production. In China, the world's largest producer, alliances have been signed and a $293 million plant was scheduled to begin deposit exploration in the summer of 2013. In Indonesia, also an important country in tin production, raw material production in 2012 increased by 19% compared to 2011. In Egypt, Gisppsland Ltd. discovered a new cassiterite deposit in 2011 that enabled investment for exploration in the following years. In Bolivia and Congo, the government that cooperated to increase the domestic production of the two countries, promoting joint ventures, that is, unions of companies with the state to exploit tin. What probably caused the fall in tin production in the years leading up to the increase may have been caused by the financial preparation of the main producing countries to have no problems at the time when capital was being directed to the construction of new mines (JAMES, 2013).

Asia is the continent with the largest number of washable tin reserves, with 31.25% of the world's reserves in China and 16.66% in Indonesia, enabling the exploitation of the raw material. Despite the position that Brazil presents in production, it has the 3rd position in the amount of proven reserves and its production is not greater just because these reserves are distributed throughout the country irregularly, hindering the processes of concession of mining for the exploitation of tin. Australia probably ranked last in the major countries because it has only 3.75% of tin reserves (RODRIGUES, 2001; BRAZIL, 2012; 2012a).

The increase in Brazilian production was a consequence of the increase and anticipation of the purchase of tin in 2011, made by the United States, the main buyer of the raw material extracted in Brazil. With the purchase guaranteed, the investment in production became effective, increasing Brazilian production in the years to take advantage of the stability and receptivity of the international market (BRASIL, 2012; 2018).

The production of contained tin probably grew in the country thanks to investments made by mining companies to improve extraction. TABOCA Mining, for example, invested R$1.25 billion in the Pitinga mine, determining production projections of up to 7,494 t of Sn-contained, again increasing production that had a considerable fall in the mine in 2010 and 2011, with only 1,451 t and 1,354 t of material respectively (ACANTHE, 2014).

The main destinations of the product exported by Brazil bought more tin in the period researched. This is the case of the United States, for example, which has repurchased the raw material in greater quantity from 2011, increasing export numbers. Another key factor was the $50.2 million surplus that the Brazilian balance achieved in international trade in 2011. The import did not beat the export data because Brazil sells more tin than it buys and, although Bolivia, for example, bought 1.8 kt of tin in 2011, this amount represents 82% of imports of the year, making the amount of tin purchased by Brazil low (BRASIL, 2016; 2018).

The apparent consumption of tin in Brazil suffered the impact of international crises in 2011, caused by the recession of 2008. It was natural for small and medium-sized companies in emerging countries, such as Brazil, to suffer falls in growth and sales due to the disorder in the international market during the period. Brazilian tin buyers went through a period of spending control and this promoted the reduction of raw material purchases for domestic consumption. However, the increase in exports of raw materials contributed to the increase in domestic consumption in 2013 and 2014, because the capital acquired from the sale of tin made the money circulate within the national trade of the sector, giving greater security for the purchase of tin for domestic consumption (CUTER and KON, 2008; VIEIRA, 2011).

According to the London Metal Exchange, the world tin peaked in April 2011, with the ton costing $32,975. Its lowest value was $14,925 per tonne, which was in February 2010. From mid-2013 the price of tin was more stable, with values very close, but closing the year 2014 with a fall in the value of the ton, US$19,095. These prices are related to the world market, directly influencing the price of Brazilian tin. The price of the internal metal followed the logic of the international market, but with lower values. The probable cause for this decrease in the ton price is that tin is sold in FOB and, as Brazil that is the supplier of the product does not transport it, customers probably get more affordable prices to reward the freight of the raw material (LME, 2018).

CONCLUSION

Tin went through a relatively positive period between the years surveyed. It was observed that the crises in the international market could not affect production so strongly that it increased from investments in the extraction of raw materials. Although Brazil is not the main holder of reserves of tin-rich ores, it proved very active and firm in its production, taking advantage of the opportunities that the world market has proposed to increase the prospection and extraction of raw materials. The result was the increase in apparent consumption in full economic complications that the country was going through and variations that the price of tin suffered during the years of the research.

Production

REFERENCES

ACANTHE, T. Polo Mineral do Amazonas. 2014. Disponível em: < http://www.ahkbrasilien.com.br/fileadmin/ahk_brasilien/portugiesische_seite/departamentos/Cooperacao_e_Desenvolvimento/Polo_Mineral_do_Amazonas.pdf >. Acesso em: 20 de dezembro de 2017.

BRASIL. Acesse Aqui os Dados Sobre Economia Mineral., 2012. Disponível em: < http://www.ibram.org.br/150/15001002.asp?ttCD_CHAVE=185736 >. Acesso em: 04 de maio de 2018.

______. Informações e Análises da Economia Mineral Brasileira Brasilia: Instituto Brasileiro de Mineração IBRAM, 2012a. 68p.

______. Exportação. 2015. Disponível em: < http://idg.receita.fazenda.gov.br/orientacao/aduaneira/importacao-e-exportacao/despacho-aduaneiro-de-exportacao. >. Acesso em: 30 de dezembro de 2017.

______. Anuário Mineral Brasileiro: Principais Substâncias metálicas. Brasília: Departamento Nacional de Produção Mineral DNPM 2016.

______. Estanho. 2018. Disponível em: < http://www.mdic.gov.br/legislacao/9-assuntos/categ-comercio-exterior/482-metarlurgia-e-siderurgia-6. >. Acesso em: 04 de janeiro de 2018.

BROCCHI, E. A. Os Metais: Origem e Principais Processos de Obtenção. Rio de Janeiro, 2017. Disponível em: < http://web.ccead.puc-rio.br/condigital/mvsl/Sala%20de%20Leitura/conteudos/SL_os_metais.pdf >. Acesso em: 30 de dezembro de 2017.

CUTER, J. C.; KON, A. Cartel internacional do estanho: a importância da indústria brasileira na quebra do conluio. Rev. Economia e Sociedade, v. 17, p. 157-171, 2008.

DNPM. Mineração. Brasília: Departamento Nacional de Produção Mineral DNPM 2017.

______. Estanho (Sn). Brasília: Departamento Nacional de Produção Mineral DNPM 2017a.

GANEM, R. S.; FILHO, A. F. F.; GANEM, R. S. IMPACTOS SOCIOAMBIENTAIS DA MINERAÇÃO: Estudo de Caso em Pedreira, Ilhéus, BA. IV Congresso Baiano de Engenharia Sanitária e Ambiental – COBESA. Cruz das Almas, Bahia 2016.

IPEA. O que é? FOB. 2010. Disponível em: < http://desafios.ipea.gov.br/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=2115:catid=28&Itemid=23 >. Acesso em: 07 de novembro de 2017.

JAMES, F. C. J. Minerals Yearbook: Tin. United States (USGS). U.S. Geological Survey, 2013. Disponível em: < https://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/tin/index.html#myb >. Acesso em: 27 de dezembro de 2017.

LME. Tin Historical Price Graph. 2018. Disponível em: < https://www.lme.com/en-GB/Metals/Non-ferrous/Tin#tabIndex=2 >. Acesso em: 04 de janeiro de 2018.

RAMOS, C. R. Estanho na Amazônia: o apogeu e ocaso da produção. Novos Cadernos NAEA, v. 6, p. 39-60, 2003.

RODRIGUES, A. F. S. Estanho. Balanço Mineral Brasileiro. Brasilia: Departamento Nacional de Produção Mineral DNPM 2001.

USGS. Tin Statistics and Information. 2016. Disponível em: < https://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/tin/. >. Acesso em: 21 de novembro de 2017.

______. Tin Statistics and Information. 2017. Disponível em: < https://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/tin/. >. Acesso em: 21 de novembro de 2017.

VIEIRA, J. G. S. A Crise Econômica de 2011. Curitiba PR, 2011. Disponível em: < http://www.santacruz.br/v4/download/janela-economica/2011/14-a-crise-economica-de-2011.pdf. >. Acesso em: 04 de maio de 2018.

High school student. Technical Course in Mining. Federal Institute of Basic, Technical and Technological Education of Amapá (IFAP).

[1] Materials Technologist. Master in Materials Science and Engineering. Researcher Professor, Federal Institute of Basic, Technical and Technological Education of Amapá (IFAP)

[2]

Biomedical. PhD in Tropical Diseases. Researcher Professor, Federal University of Amapá (UNIFAP).

[3] Biologist. Doctor of Tropical Diseases. Researcher Professor at the Federal University of Pará (UFPA).

[4] Biologist. Doctor of Tropical Diseases. Researcher Professor at the Federal University of Pará (UFPA).

[5] Theologian. PhD in Clinical Psychoanalysis. Researcher at the Center for Research and Advanced Studies, São Paulo, SP.

[6] Biologist. PhD in Theory and Behavior Research. Researcher Professor, Federal Institute of Basic, Technical and Technological Education of Amapá (IFAP)