BIBLIOMETRIC REVIEW

MALOSSO, Milena Gaion [1], BARBOSA, Edilson Pinto [2], SANTOS, Ivan Monteiro dos [3]

MALOSSO, Milena Gaion. BARBOSA, Edilson Pinto. SANTOS, Ivan Monteiro dos. Bibliometric review of the economic potential and use of medicinal plants in Brazil. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year. 08, Ed. 07, Vol. 03, pp. 114-133. July 2023. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/biology/use-of-medicinal-plants, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/biology/use-of-medicinal-plants

ABSTRACT

The objective of this study was to conduct a bibliometric review on the economic potential of medicinal plants used as phytotherapeutics. To achieve this, a search was conducted on Google and Google Scholar websites, without a specific time frame, using terms such as medicinal plant, medicinal plants, economic value of medicinal plants, economic potential of medicinal plants, medicinal plants used by the Unified Health System (SUS), and the word “leaflet” followed by the common or scientific name or the phytomedicine. Based on the texts found through this search, this article was elaborated. As a result, the history of medicinal plants and the evolution of their use were introduced, considering them as sources of biologically active molecules that currently hold significant economic potential in the pharmaceutical industry market. Additionally, due to being lower-cost alternatives compared to allopathic medicines, they are widely used by the SUS. The study of new phytotherapeutics is a highly promising field, particularly in Brazil, which possesses an immeasurable quantity of plants with medicinal properties. However, significant research and effective development of new phytomedicines require increased financial investment in the area to boost the production of new Brazilian phytopharmaceuticals and genuine phytotherapeutics. This, in turn, will generate higher profits in this sector.

Keywords: Bibliometric review, Medicinal Plants, Phytotherapeutics, Economic Value, Phytomedicines used by SUS.

1. INTRODUCTION

Humans have used medicinal plants to cure their ailments since the beginning of their existence (GADELHA et al., 2013), as they would experiment with plants randomly until finding the one that cured a particular disease. Thus, it can be noted that the foundation of knowledge about phytotherapy and the use of medicinal plants was established gradually through trial-and-error processes (ANDRADE, 2018). These processes varied from identifying and selecting the species, the plant part, and the appropriate quantity of the plant to treat a disease, to determining the correct planting season for each of the species they used (ALMEIDA; RAMALHO; CASTRO, 2022). Over time, the slow and lengthy process of learning the development of techniques for preparing phytotherapeutics and their proper use was passed down from generation to generation (MONTEIRO and BRANDELLI, 2017), eventually becoming part of the collective memory that exists to this day on this subject (SILVA, 2022).

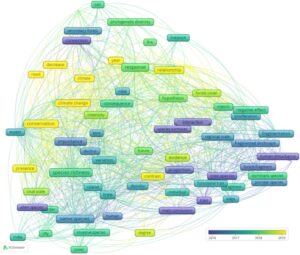

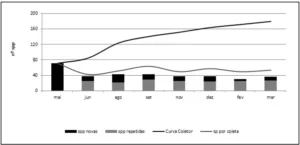

The objective of this study was to conduct a bibliometric review on medicinal plants used as phytomedicines by the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS) and the economic potential of plants in Brazil and worldwide. To achieve this, a search was conducted on Google and Google Scholar websites, without a specific time frame, using terms such as medicinal plant, medicinal plants, economic value of medicinal plants, economic potential of medicinal plants, medicinal plants used by SUS, and the word “leaflet” followed by the common or scientific name or the phytomedicine. A total of 581 texts were found, and using exclusion criteria such as providing scientific names, biomolecule names, biological activity, indication of use by SUS, and numerical financial data, only the fifty-five texts listed in the bibliography of this article were utilized to construct this text.

2. BRAZILIAN MEDICINAL SPECIES AND BIOACTIVE PRINCIPLES

The consumption of phytotherapeutics and medicinal plants is popularly based on the myth “if it’s natural, it’s harmless,” which is not true. Improper use of these substances can lead to various reactions such as intoxication, nausea, irritation, edema, and even death, much like any other medication (NUNES and MACIEL, 2017).

According to ANVISA (2020), a distinction can be made between medicinal plants and phytotherapeutics:

As plantas medicinais são aquelas capazes de aliviar ou curar enfermidades e têm tradição de uso como remédio em uma população ou comunidade. Para usá-las, é preciso conhecer a planta e saber onde colhê-la, e como prepara-la. Normalmente são utilizadas na forma de chás e infusões.

Phytotherapeutics are essentially medicinal plants that have been processed and transformed into pharmaceuticals, which are then sold in pharmacies (SILVA et al., 2017). The industrialization process of these medicinal plants helps prevent contamination by microorganisms and foreign or even toxic substances. It also standardizes the appropriate dosage and correct form of medicinal administration, ensuring greater safety in use (LEAL and CAPOBIANCO, 2021). However, before being marketed, industrialized phytotherapeutics must undergo mandatory regulation by Anvisa (ALBUQUERQUE, SANTOS, RODRIGUES, 2022).

Phytotherapeutics can also be prepared in authorized compounding pharmacies under sanitary surveillance, and in this case, they do not require sanitary registration but do need a prescription from licensed professionals (FRANCA et al., 2021).

Thus, according to Silva, Furtado, and Damasceno (2021):

O medicamento fitoterápico é o produto finalizado obtido de planta medicinal, ou de seus derivados, com exceção de substâncias isoladas farmacologicamente ativas, com a finalidade profilática, paliativa ou curativa, podendo ser simples, quando é proveniente de uma planta, ou composto, isto é, constituído de mais de uma planta. Não é considerado um medicamento fitoterápico aquele que em sua composição tiver substâncias ativas isoladas, sintéticas ou naturais, nem suas associações com extratos vegetais.

Thus, for plants to be considered medicinal and eligible for industrialization as phytotherapeutics, they must possess some molecule with biological activity (BEVILAQUA et al., 2015).

Silva, Furtado, and Damasceno (2021) identified in their studies the sixteen main Brazilian medicinal species used as phytotherapeutics in the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS), as indicated by the GM Ordinance 1.102 of May 12, 2010, from the Ministry of Health. These include Artichoke (Cynara scolymus), Brazilian Pepper Tree (Schinus terebinthifolius), Cascara Sagrada (Rhamnus purshiana), Espinheira-Santa (Maytenus ilicifolia), Devil’s Claw (Harpagophytum procumbens), Guaco (Mikania glomerata), Soybean (Glycine max), Cat’s Claw (Uncaria tomentosa), Aloe Vera (Aloe Vera), Peppermint (Mentha piperita), Psyllium (Plantago ovata), Willow (Salix Alba), Calendula (Calendula officinalis), Lemon Balm (Melissa officinalis), Chamomile (Matricaria chamomila), Boldo (Gymnanthermum amygdalinum), Whitebrush (Lippia alba), and Ironwood (Caesalpinea ferrea).

All these plants have biomolecules with biological activity, and their indications are described as follows:

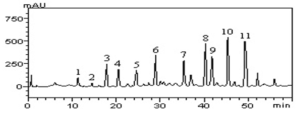

Artichoke (Cynara scolymus) is used in the formulation of Lipotron at a dosage of 0.10 mL/100 mL. It is indicated for cases of hepatic insufficiency, cholagogue, laxative, and digestive disturbances resulting from liver diseases (MELLO, MELLO, LANGELOH, 2009). The leaves are used for the production of phytotherapeutics due to their chemical components, including phenolic derivatives such as caffeoylquinic acids, flavonoids, sesquiterpenes, and some aliphatic acids, which are used as antioxidants (NASCIMENTO, DUTRA, MELO, 2020).

According to the Ministry of Health (BRAZIL, 2021), based on the Formulário de Fitoterápicos of the Brazilian Pharmacopoeia, Brazilian Pepper Tree (Schinus terebinthifolius) has bioactive principles primarily in the dried stem bark, but the leaves, fruits, and roots are also used in popular applications. Chemotaxonomic studies of this species have identified biomolecules such as the terpenes aristolone and α-amyrin, and phenolic compounds like luteolin, quercetin, camphor, ethyl gallate, catechin, gallocatechin, and agathisflavone, which have cicatrizing activity. Tannins such as gallic acid, ethyl gallate, methyl gallate, trans-catechin, quercitrin, and afzelin have been found in the leaves, exhibiting antifungal activity. Isolated flavonoids from the fruits, such as rutin, quercetin, and apigenin, are used as anti-inflammatories. The phytotherapeutic is formulated as a gel of dry leaf extract at a dose of approximately 0.75 mg/mL of this plant and is recommended for vaginal use to treat skin irritation, larvicides against leishmaniasis, cancerous tumors, fungi, bacteria, among other uses. A phytotherapeutic called Kronel, at a dose of 3.996 mL/6.0g, is indicated for the treatment of cervicitis, vaginitis, and cervicovaginitis (SITINIKI[11], 2023).

Aloe Vera (Aloe vera) constitutes the phytotherapeutic product Aloax, presented in the form of tubes with the mucilaginous gel of this plant, at a dosage of 50.00 mg. This product is used in the treatment of 1st and 2nd-degree thermal burns caused by hot water, fire, and excessive exposure to sunlight, acting as a healing agent on the injured tissue (Silva, 2023). As described by SITINIKI[6] (2023), Aloe extract is standardized to the polysaccharide mannosyl-6-phosphate, which is responsible for the healing process, occurring through direct stimulation of macrophages and fibroblasts. In the case of the latter, it increases collagen and proteoglycan synthesis, thus promoting tissue replacement in the injured areas. Furthermore, according to this same author:

O mecanismo de ação baseia-se na inibição de produtos derivados metabolismo do ácido araquidônico, tais como o tromboxano B, limitando por sua vez a produção de prostaglandina F 2α, prevenindo-se a isquemia dérmica progressiva, especialmente em casos de queimaduras, ulcerações causadas pelo frio, machucados por acidente elétricos e usa intrarterial abusivo de drogas.

Boldo (Gymnanthermum amygdalinum) is provided by the Brazilian Unified Health System (SUS) through the phytotherapeutic Klein, which is a tincture with a dosage of 1.0 mL/mL, standardized to 0.20 mg (0.02%) of total alkaloids calculated as boldine biomolecule. It is indicated for mild digestive disorders, as it reduces intestinal spasms by acting as a relaxant on the intestinal smooth muscles. It is also used for the treatment of hepatobiliary disorders with cholagogue and choleric action (LEWGOY, 2023).

According to Florien (2023), Calendula (Calendula officinalis) has many bioactive biomolecules in its composition. However, it is primarily used as a reepithelializing and healing agent, working in conjunction with mucilages, flavonoids (especially quercetin-3-O-glycoside), triterpenes, and carotenoids. This activity stimulates the metabolism of glycoproteins and collagen tissue. Ointments with 5% Calendula floral extract in combination with allantoin are the most commonly found in pharmacies (SITINIKI[5]).

According to Sitiniki[12] (2023), Camomile (Matricaria chamomila) is marketed under the name Matricaria chamomilla 1DH by Simões Laboratory, in boxes containing 300 mg papers with 0.03 mL of Chamomilla 1DH in 300 mg of excipient (lactose) q.s. The bioactive molecules of this plant are levomenol ((-)-α-bisabolol) and flavonoid derivatives, presenting anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and healing activities. Flavones lead to the suppression of arachidonic acid metabolism, increased ATP production, and creatinine phosphate in the skin, resulting in increased oxidative phosphorylation in the liver mitochondria.

Gutierrez (2012) clarifies that Cascara Sagrada (Rhamnus purshiana) is a phytotherapeutic drug produced by Herbarium in the form of hard capsules from the dried extract of the bark of this plant, with a dosage of 75 mg standardized to 22% hydroxyanthracene derivatives expressed as cascaroside A, indicated for cases of constipation.

Furthermore, according to Gutierrez (2012):

este extrato é composto por derivados do 1,8-di-hidroxi-antraceno que possuem um efeito laxante. Os cascarosídeos A e B são uma mistura de glicosídeos -C-antrona e -O- -glicosídeos. Os cascarosídeos C, D, E e F são 8-O-β-D-glicosídeos que não são metabolizados pelas enzimas digestivas do intestino delgado, e por isso são pouco absorvidos. Sendo assim, são convertidos em metabólitos ativos (principalmente emodina-9-antrona) por bactérias no intestino grosso. Existem dois mecanismos de ação diferentes: 1 – Age estimulando a motilidade do intestino grosso, resultando no aumento do transito do cólon. 2 – Influencia nos processos de secreção por dois mecanismos concomitantes: inibição da absorção de água e eletrólitos (Na+, Cl-) nas células epiteliais do cólon (efeito antiabsortivo); e o aumento da passagem paracelular pelas junções de oclusão (tight junctions), estimulando a secreção de água e eletrólitos (efeito secretagogo), resultando em concentrações aumentadas dos mesmos no lúmen do cólon. O tempo estimado para o início da ação é de 6 a 12 horas após sua administração. E a farmacocinética ocorre porque os Glicosídeos β-0-ligados não são metabolizados pelas enzimas digestivas humanas e consequentemente não são absorvidos no intestino delgado. São hidrolisados no cólon pelas bactérias intestinais, formando os metabólitos ativos (principalmente emodina-9- -antrona). As antraquinonas agliconas absorvidas são transformadas em seus correspondentes glicuronídeos e derivados sulfatos.

According to Pereira et al. (2014), Lemon Verbena (Lippia alba) is sold in the form of a tincture composed of 10 mg of crushed leaves and flowers and 100 mL of 70% ethyl alcohol q.s., containing the biomolecules geranial and carvone, indicated for migraine prevention and used as an analgesic.

According to Sitiniki[13] (2022) Lemon balm (Melissa officinalis) has as its active principle the biomolecule citral, which is indicated as a carminative for reducing intestinal gases, an antispasmodic preventing spasms and cramps in the stomach and intestines, and a mild anxiolytic. The recommended dosages are 40 drops (2.0 mL) diluted in water twice a day for children up to 12 years old and 60 drops (3.0 mL) diluted in water twice a day for adults.

Brazilian Peppertree (Schinus terebinthifolius) is used for relief from indigestion and as an adjunct in the treatment of gastritis and stomach and duodenal ulcers. The phytotherapeutic is presented in the form of hard capsules with 380 mg of leaves from this species and an excipient capsule q.s.q. (starch), equivalent to 13.30 mg of total tannins expressed as pyrogallol. It should be ingested as per medical prescription (SITINIKI[7], 2022). According to this author, this plant contains the triterpenes maitenin, which has antimicrobial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, and friedelin and friedelanol, in addition to condensed tannins from the catechin group that have an antiulcerogenic effect.

SITINIKI[9] (2022), recommends Devil’s Claw (Harpagophytum procumbens) for the treatment of moderate joint pain and acute low back pain, acting as an anti-inflammatory, antirheumatic, and analgesic agent by inhibiting the synthesis of prostaglandins produced in the irritative phase of the inflammatory process. The phytotherapeutic is presented in the form of tablets containing 200 mg of dry extract from the plant’s root, equivalent to 10 mg of total iridoids calculated as harpagosides. The galenic preparations perform a gastric protection function, demonstrating analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects due to reduced stomach acidity.

Guaco (Mikania glomerata) is used to treat respiratory tract conditions such as persistent cough, productive cough, and hoarseness. The recommended administration is 2.5 mL orally, twice a day. This phytotherapeutic contains coumarins, which induce a relaxing effect on the smooth muscles of the airways and also have bronchodilator and expectorant properties, as they block acetylcholine receptors present in the respiratory system, causing bronchoconstriction and increased secretion (SITINIKI[15], 2022).

According to Sitiniki[14] (2022), the Peppermint (Mentha piperita) is recommended as a carminative for relief from colic and flatulence and also as an expectorant. For adults, the recommended dosage is 10.0 mL, and for children, it is 5.0 mL of the phytotherapeutic syrup three times a day. According to this author:

O extrato fluido/seco obtido de folhas e caules contém flavonóides, ácidos fenólicos e óleo essencial (1 a 3%). O óleo é constituído por mentol e derivados triterpenos. Esse grupo de substâncias atua como antiespasmódico, colerético, colagogo e carminativo.

Sua ação farmacológica deve-se, principalmente, aos óleos voláteis, produzindo uma potente ação espasmolítica com relaxamento da musculatura lisa e reduzindo o tônus docárdia. Os flavonóides também contribuem para a atividade espasmolítica e os ácidos fenólicos para o efeito colerético.

According to ANVISA [4] (2011), the Jucá (Caesalpinia ferrea) is marketed in the form of a gel containing a glycolic extract of the fruit of this plant at a dosage of 5%. It is indicated as a healing and antiseptic agent and should be applied to the affected area three times a day. Brasil (2006) reported in their study that:

Estudo pré-clínico realizado com os taninos: ácido gálico e metil galato, isolados dos frutos deta espécie, demonstraram que estas substâncias exerceram ação anticarcinogênica em modelos de indução de câncer de pele em animais e outros constituintes isolados do fruto, como os derivados da acetofenona, demonstraram uma potente atividade inibitória tumoral em ensaio de ativação antigênica com o vírus Epstein Barr.

Plantain (Plantago ovata) is a phytotherapeutic recommended for diarrhea, constipation, and as an aid in the treatment of Crohn’s disease. It also serves as an adjunct in the treatment of hemorrhoids, fissures, and anal abscesses. It is sold in the form of 3.5 g sachets, which should have the effervescent powder from the seed husk diluted in 150 mL of cold water. (SITINIKI[17], 2020). According to Sitiniki[16] (2022):

O principal componente desta casca é uma mucilagem que contém uma hemicelulose composta por 85% de ácidos arabinoxilanos, com pequena proporção de ramnose e de ácido galacturônico. A atividade terapêutica é decorrente da fibra dietética, altamente solúvel, que constitui seu princípio ativo: cada 100 g de produto administrado ao paciente contém 49 g de fibras solúveis. O mecanismo de ação da fibra ocorre por aumento do volume e do grau de hidratação das fezes, contribuindo para a normalização do hábito intestinal. Adicionalmente, o aumento da massa fecal ativa a motilidade intestinal, sem efeitos irritativos.

Alguns tipos de fibras, incluindo a casca da semente desta planta possuem efeitos hipocolesterolêmicos, principalmente devido à diminuição da absorção intestinal de colesterol e ao aumento da excreção de colesterol e de ácidos biliares, reduzindo assim os níveis séricos de colesterol.

A Plantago ovata apresenta diferentes mecanismos de ação, podendo ser indicado para diferentes quadros patológicos. É uma boa alternativa como tratamento coadjuvante da doença inflamatória intestinal (doença de Crohn, colite ulcerosa) em períodos de remissão, pois melhora a sintomatologia e diminui as recidivas. Além disso, Plantago ovata é eficaz em doenças cuja etiologia se encontra principalmente na falta de fibras na alimentação, como é o caso da doença diverticular do cólon.

According to Sitiniki[10] (2020), the Willow (Salix alba) has the dry extract of its leaves used in the treatment of painful inflammatory conditions such as rheumatism, neuralgia, and inflammatory processes in general, in addition to preventing thromboembolism and treating dysmenorrhea due to difficulty in eliminating clots. The recommended dosage is 15 mL of the extract three times a day. The action of this plant occurs as follows:

“O glicosídeo de salicilina (salicósido) e seus éteres ao chegar a nível intestinal são absorvidos transformando-se em saligenina, para posteriormente serem metabolizados e rransportados ao fígado, onde se transformam por oxidação em ácido salicílico 1. As ações farmacológicas estudadas até o momento, estão centralizadas no ácido acetilsalicílico, podendo- se resumir as mesmas em três itens básicos: ação antitérmica, ação analgésica/antiinflamatória e ação antiagregação plaquetária.

A atividade antitérmica está baseada na capacidade que tem de inibir a enzima ciclo-oxigenase que intervém na formação de prostaglandinas, as quais atuam nos centros moduladores da temperatura no hipotálamo.

Desta maneira, a inibição exercida sobre a ciclo-oxigenase e o correspondente decréscimo na produção de prostaglandinas PGE2 a partir do ácido araquidônico também tem relação com a diminuição da dor e da inflamação 2 (SITINIKI[8]”.

As per SITINIKI[10], the Soy (Glycine max) is recommended for hot flashes and sweating associated with menopause. It is marketed in the form of a tablet composed of 125 mg of dry extract of the plant, equivalent to 50 mg of total flavones genistein and daidzein. The pharmacodynamic properties are as follows:

As isoflavonas são fitoestrogênios da soja, sendo similares em estrutura ao estradiol, principal hormônio feminino. Exercem efeitos estrogênicos e antiestrogênicos no metabolismo humano, que dependem de vários fatores como a concentração de estrogênios endógenos, as características individuais como idade e fase da menopausa e concentração de fitoestrogênios. Os fitoestrogênios exibem uma atividade estrogênica mais fraca que o 17 β-estradiol, na ordem de 10–2 a 10–3.

No organismo, os estrogênios interagem com os receptores α e β. Os receptores α são mais abundantes no sistema reprodutor feminino (glândulas mamárias e útero) enquanto os β predominam em outros tecidos como trato urogenital, ossos, vasos sangüíneos e sistema nervoso central. Os fitoestrogênios se complexam ao receptor α de maneira fraca, produzindo ações antiestrogênicas, e com o receptor β de maneira quase igual aos estrogênios endógenos, produzindo suas ações estrogênicas, dependendo da saturação dos receptores e do nível circulante de estrogênios, assemelhando-se à ação dos moduladores seletivos dos receptores de estrogênios. Decorrem desta interação suas ações sobre o centro termorregulador hipotalâmico e a consequente atividade sobre os sintomas da menopausa, tais como os fogachos e a sudorese associados ao climatério, sem acarretar, em geral, proliferação endometrial.

Também associadas às isoflavonas, relacionam-se suas ações antioxidantes e antiateroscleróticas, tanto através do aumento da função das enzimas antioxidantes, como pelas influências benéficas obtidas sobre a reatividade vascular e a progressão da doença aterosclerótica. Além das ações hormonais, as isoflavonas apresentam potente ação inibitória sobre a tirosina-quinase, podendo afetar a DNA toposisomerase II e a quinase ribossomal S6, com grande influência sobre o ciclo celular, diferenciação, proliferação e apoptose, o que pode correlacionar-se a um aspecto preventivo do aparecimento de neoplasias.

Cat’s Claw (Uncaria tomentosa), according to Sitiniki[18] (2020), the Fitotherapy is an age-old, cost-effective therapeutic practice based on the healing properties of medicinal plants. Phytotherapeutic medicines are used for the treatment and prevention of pathologies due to their proven bioactive substances. Hence, they are an excellent option for medications to be acquired and used by the Unified Health System (SUS).

3. ECONOMIC POTENTIAL OF PHYTOTHERAPEUTICS IN BRAZIL AND WORLDWIDE

Medicinal plants are important sources of biologically active natural products, many of which serve as models for the synthesis of a large number of drugs (PINHEIRO; SARGEBINI JUNIOR; PINHEIRO, 2013). According to the World Health Organization, 80 to 85% of the population in developing countries lacks access to modern medicine due to poverty and relies mainly on medicinal plants to meet their primary health needs (SOUZA et al., 2013). Over 1 billion people worldwide (approximately 20%) live in extreme poverty and suffer and die due to a lack of basic medical care (ALMEIDA and RAMALHO, 2017). In developing countries, 766 million people die from easily preventable diseases, with approximately 26% being children who could be cured with a few cents using medicinal plants (RAMOS, 2006; NASCIMENTO, 2015).

The value of natural products from medicinal plants to society and the global economy is immense (BALZINI, 2016). According to Rodrigues, Nogueira, and Parreira (2008), the global drug market is estimated at $300 billion annually, with 40% of drugs directly or indirectly derived from natural sources, 75% of which are of plant origin. Consequently, the pharmaceutical industry invests around $120 million in R&D for phytotherapeutics (PONCIANO et al., 2018).

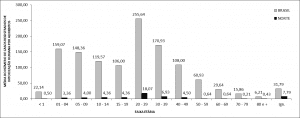

Veiga Junior, Pinto, and Maciel (2005) estimated that the European market alone reached $7.0 billion, with consumption in Germany accounting for approximately 50% of that market, i.e., about $3.5 billion, representing approximately $42.90 per capita. To give an idea of the value annually moved, here is the ranking of sales of medicinal products in the following countries: USA $321 billion, Japan $96.3 billion, Germany $45.3 billion, France $43.7 billion, China $40.1 billion, Italy $29.2 billion, Spain $25.5 billion, Brazil $22.1 billion, UK and Canada $21.6 billion, Russia $13.1 billion, India $12.3 billion, South Korea $11.4 billion, Australia $10.8 billion, Mexico $10.8 billion, Peru $10.6 billion, Greece $7.8 billion, Poland $7.0 billion, Netherlands $6.9 billion, and Belgium $6.8 billion (SANTOS and FERREIRA, 2012). These figures have attracted the interest of the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies, which currently invest in phytochemical studies, characterization of potential bioactive compounds, as well as pharmacological tests, bioactivity modes, and determination of active sites of compounds extracted from plants (ASSUMPÇÃO, SILVA, MENDES, 2022).

In Brazil, the Ministry of Health (BRASIL, 2006) reported that the sales of medicines in pharmacies containing exclusively plant-derived active ingredients amounted to $550 million annually. Data presented by the National Health Surveillance Agency (Anvisa) show that, in 2017 alone, the segment moved R$69.5 billion, commercializing a total of 6,587 products (FIA, 2020).

The development of a single drug costs around $720 million (BUSCATO, 2014), and only 1 in every 10,000 chemical compounds studied with pharmacological potential makes it to the market (BRASIL, 2022). Despite these risks, a single compound can generate approximately $1 billion in profit annually when introduced to the market (SANTOS and FERREIRA, 2012). An important example of new drug investigation is the study conducted by the National Cancer Institute in the USA, where approximately 114,000 plant extracts from 35,000 plant species were evaluated between 1960 and 1982, aiming to find a new drug against cancer. In this study, Taxol was discovered, a substance currently widely used in the treatment of all types of cancer patients (MALOSSO, 2007).

According to Conceição (2013), out of 10,000 compounds studied, an average of 250 present some promising biological activity; only 5 reach the clinical trial phase, and only 1 is registered as a drug. Only 8% of the species of the Brazilian flora have been studied in the search for bioactive compounds (KESSIN et al., 2018), and 1,100 plant species have been evaluated for their medicinal properties (ABREU, 2019).

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Upon conducting the proposed bibliometric search, the sixteen species of medicinal plants – Aroeira, Babosa, Boldo, Calendula, Chamomile, Cascara-sagrada, Lemon balm, Espinheira-santa, Devil’s claw, Guaco, Mint, Jucá, Soy, Platago, Willow, and Cat’s Claw – most used by SUS, for presenting proven phytotherapeutic biological activity, efficacy, and safety confirmed by several scientific studies, were described. Their indications vary widely, and they can be used as analgesics, anti-inflammatories, wound healers, laxatives, antispasmodics, bronchodilators, among many others. According to online research conducted on major pharmacy and drugstore websites such as Call Farma, Pague Menos, Farma Bemol, Drogaria Pacheco, Farmácia Santo Remédio, Drogaria Minas Brasil, the phyto-medicines are much cheaper when compared to allopathic medications indicated for the same treatment, as can be seen in a survey carried out at Droga Raia, in the example of Kronel, indicated for the treatment of vaginal inflammation caused by fungi and bacteria, a box of this phytotherapeutic containing 1 tube of 60 g of vaginal gel with 10 applicators costs on average R$96.00 (ninety-six reais) and the intimate soap with the same biomolecule costs on average R$29.49 (twenty-nine reais and forty-nine cents). Meanwhile, in the same drugstore, an allopathic medicine Gino-canestein Calm with the same function, in the form of gel with 10 tubes, costs R$114.14 (one hundred and fourteen reais and fourteen cents) and the intimate soap, R$54.19 (fifty-four reais and nineteen cents). Thus, as observed, the phyto-medicine in the form of vaginal gel is 15.89% cheaper than the allopathic medicine, and the intimate soap is 54.41% cheaper, thus demonstrating greater cost savings for Brazil in obtaining phyto-medicines to be used in SUS.

5. FINAL REMARKS

Brazil is a country with mega-biodiversity, especially concerning medicinal plants, which are rich in biomolecules with pharmacological activities that can be used to generate high profits for the country through the sale of phytotherapeutics and save costs in the SUS. However, for this to happen, there needs to be greater investment from the Brazilian government and pharmaceutical industries in this research area to identify new plants with effective biological activities that can be used in the treatment of human diseases at lower costs, thus reducing the government’s healthcare costs for the Brazilian population while maintaining the quality, efficacy, and safety in the use of plant-based medicines for the treatment of the Brazilian population.

REFERENCES

ABREU, Felipe Cordeiro de. Estudo comparativo de planta medicinais utilizadas na produção de fitoterápicos tradicionais do centro de saúde alternativa de muribeca em relação à indústria farmacêutica no Brasil. Dissertação (Bacharelado em Economia Doméstica) – Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco, 57 p., 2019.

ALBUQUERQUE, Janaína Vital de; SANTOS, Erlene Roberta Ribeiro dos; RODRIGUES, Gilberto Gonçalves. Das raízes históricas às folhas e práticas dos fitoterápicos: a etnobotânica no processo saúde doença. REVISTA EA. 2022. Retirado de: https://www.revistaea.org/artigo.php?idartigo=4353. Acesso em 16/05/2022.

ALMEIDA, Adriana Maria Pereira de; RAMALHO, Talles Antônio Santos; CASTRO, Leandro Almeida de. Fitoterapia: o uso de plantas medicinais e fitoterápicos no cuidado a saúde. Revista Saúde dos Vales, v. 1, n. 1, 2022.

ALMEIDA, Thaynara Sarmento Oliveira; RAMALHO, Salomão Nathan Leite. Delineamento das doenças tropicais negligenciadas no Brasil e o seu impacto social. Inter Scientia. V. 5, n. 1, 2017.

ANDRADE, Sanderley Emanuel Oliveira de. Estudo etnobotânico e etnoveterinário de plantas medicinais na comunidade da Várzea Comprida dos Oliveiras, Pombal, Paraíba, Brasil. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso de Bacharelado em Agronomia. Universidade Federal de Campina Grande, 40 p, 2018.

[4] ANVISA – Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Formulários de Fitoterápicos Farmacopéia Brasileira. 1ª Edição. ANVISA: Brasília. 2011. 126p.

ANVISA – Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Medicamentos fitoteápicos e plantas medicinais. 2020. Disponível em: <https://www.gov.br/anvisa/pt-br/assuntos/medicamentos/fitoterapicos>. Acesso em: 16 maio 2023.

ASSUMPÇÃO, Isabel Cistina Porto; SILVA, Brunno Almeida de Carvalho; MENDES, Marisa Fernandes. Bioprospecção de plantas medicinais com potencial anticancerígeno no Brasil: caracterização e métodos de extração. Revista Fitos. 2022. Disponível em: <https://revistafitos.far.fiocruz.br/index.php/revista-fitos/article/view/1251/1028>. Acesso em: 03 maio 2023.

BALZINI, Vanderlan da Silva. Biodiversidade, bioprospecção e inovação. Ciência e Cultura. V. 68, n. 1, p. 4 – 5, 2016.

BEVILAQUA, Gilberto A. et al. Documento 394: Tecnologia de plantas medicinais e bioativas da flora de clima temperado. EMBRAPA CLIMA TEMPERADO: Pelotas/RS, 100 p., 2015.

BRASIL, Ministério da Saúde. Informações sistematizadas da relação nacional de plantas medicinais de interesse ao SUS: Schinus terebinthifolius RADDI – Anacardiaceae – Aroeira do Pará. Brasilia, 2021, 83 p.

BRASIL, Ministério da Saúde, Instituto Nacional do Câncer – INCA. Fases de desenvolvimento de um novo medicamento. 2022. Disponível em: <https://www.gov.br/inca/pt-br/assuntos/pesquisa/ensaios-clinicos/fases-de-desenvolvimento-de-um-novo-medicamento>. Acesso em: 3 maio 2023.

BRASIL, Ministério da Saúde. Política Nacional de Plantas Medicinais e Fitoterápicos. 60 p. 2006.

BUSCATO, Maristela. Desenvolver novas drogas não é tão caro quanto a indústria gostaria que você acreditasse. Revista Época, 2014. Disponível em: <https://epoca.oglobo.globo.com/saude/check-up/noticia/2017/09/desenvolver-novas-drogas-nao-e-tao-caro-quanto-industria-gostaria-que-voce-acreditasse.html>. Acesso em: 03 maio 2023.

CONCEIÇÃO, Emile. Pesquisa da FIOCRUZ Bahia visa produção de remédios para combater o câncer. Ciência e Cultura – Agência de Notícias em C&T. 2013. Disponível em: <http://www.cienciaecultura.ufba.br/agenciadenoticias/noticias/plantas-da-flora-brasileira-sao-objetos-de-estudo-para-producao-de-remedios/>. Acesso em: 03 maio 2023.

FIA, Business School. Indústria Farmacêutica, caraterísticas, setores e mercado de trabalho. 2020. Disponível em: <https://fia.com.br/blog/industria-farmaceutica/>. Acesso em: 03 maio 2023.

FLORIEN, Fitoterapia. Calêndula officinalis. 2023. Disponível em: <CALÊNDULA.pdf (florien.com.br)>. Acesso em: 19 maio 2023.

FRANCA, Manasses Almeida de; et al. O uso de fitoterapia e suas implicações. Brazilian Jornal of Health Review. v. 4, n. 5, p. 19626 – 19646, 2021.

GADELHA, et al. Estudo bibliográfico sobre o uso de plantas medicinais e fitoterápicos no Brasil. Revista Verde de Agroecologia e Desenvolvimento Sustentável. V. 8, n. 5, p. 208 – 212, 2013.

GUTIERREZ, Gislaine B. (Farmacêutica responsável). Cascar sagrada Herbarium, 2012. Disponível em: <cascara_sagrada_herbarium_8856052021_1633402840333-repaired.pdf> (bula.gratis). Acesso em: 19 maio 2023.

KESSIN, Julia Paulina et al. Atividade antioxidante de compostos fenólicos presentes em polpa e casca de goiabeira serrana. Brasilian Journal of Food Research. V. 9, n. 1, p. 141 – 153, 2018.

LEAL, Juliesly Aparecido; CAPOBIANCO, Marcela Petrolini. Utilização de fitoterápicos no tratamento de depressão. Revista Científica. v. 1, n. 1, 2021. Disponível em: <http://189.112.117.16/index.php/revista-cientifica/article/view/594>. Acesso em: 16 maio 2023.

LEWGOY, Daniel P. (Farmacêutico Responsável). Bula do Boldo Klein. Retirado de Boldo Klein: bula, para que serve e como usar | CR Disponível em: <consultaremedios.com.br>. Acessado em: 19 maio 2023.

MALOSSO, Milena Gaion. Micropropagação de Acmella oleracea (L.) R. K. Jansen e estabelecimento de meio de cultura para a conservação desta espécie em banco de gemoplasma in vitro. Universidade Federal do Amazonas. Tese de doutorado em Biotecnologia, 103 p., 2007.

MELLO, João Roberto Braga de; MELLO, Fernanda Bastos de; LANGELOH, Augusto. Fitotoxidade pré-clínica de fitoterápico contendo Aloe ferox, Quassia amara, Cynara scolymus, Gentiana lutea, Peumus boldus, Rhamnus purshiana, Solanum paniculatum e Valeriana officinalis. Latin American Journal of Farmacy. v. 28, n. 1., p. 183 – 191, 2009.

MONTEIRO, Siomara da Cruz; BRANDELLI, Clara Lia Costa (Org.). Farmacobotânica: Aspectos teóricos e aplicação. Porto Alegre: PUBMED, 2017.

NASCIMENTO, Guilherme Feitosa; DUTRA, Jéssika Veridiano; MELO, Francislete Rodrigues. Determinação de compostos fenólicos totais e atividade antioxidante de extratos dos vegetais: Unha de gato (Uncaria Tomentosa), Indiano Oli-Banum (Boswellia serrata); Gymnema (Gymnema sylvestre) E Alcachofra (Cynara scolymus). Brazilian Journal of Development., v. 6, n. 12, p. 96637 – 966560, 2020.

NASCIMENTO, Ludmila Alves. Promoção da autoeficácia materna na prevenção da diarreia infantil – efeitos de uma intervenção combinada: vídeo educativo e roda de conversa. Universidade Federal do Ceará. Dissertação de mestrado em enfermagem, 131 p., 2015.

NUNES, Josefina de; MACIEL, Michelline de. A importância da informação do profissional de enfermagem sobre o cuidado no uso das plantas medicinais: uma revisão de literatura. Revista Fitos., 2017. Disponível em: <https://revistafitos.far.fiocruz.br/index.php/revista-fitos/article/view/385/html>. Acesso em: 16 maio 2023.

PEREIRA et al. Tintura de Lippia alba (Mill) N. E. BR ex Britton & P. Wilson. Primeiro Suplemento de Formulários de Fitoterápicos da Farmacopéia Brasileira. 1ª Edição, 2014. P. 56.– 57, 2014.

PINHEIRO, Carlos Daniel Freitas; SARGEBINI JUNIOR, Ézio; PINHEIRO, Carlos Cleomir de Souza. Caracterização Química de Alfavaca Brava (Ocimum campechianum MILL.). In: II Congresso de Iniciação Científica PIBIC/CNPQ – PAIC/FAPEAM, 2013. Disponível em: <https://repositorio.inpa.gov.br/bitstream/1/4571/1/pibic_inpa.pdf>. Acesso em: 02 maio 2023.

PONCIANO, Rayanne de França et al. A viabilidade do Brasil em produzir fármacos com auxílio da tecnologia e inovação. Innovation Dialogues to acellerate industry application. v. 9, n. 1, p. 295 – 301, 2018.

RAMOS, Natália. Saúde Desenvolvimento e Diretos Humanos. Revista Interface. v. 3, n. 1, p. 11 – 31, 2006.

RODRIGUES, Waldecy; NOGUEIRA, Jorge Madeira; PARREIRA, Livian Alves. Competitividade da cadeia de plantas medicinais no Brasil: uma perspectiva a partir do comércio exterior. In: XLVI Congresso da Sociedade Brasileira de Economia. 23p., 2008. Disponível em: <https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/112833/>. Acesso em: 05 fev. 2023.

SANTOS, Emerson Costa dos; FERREIRA, Maria Alice. A indústria farmacêutica e a introdução de medicamentos genéricos no mercado brasileiro. Nexos Econômicos. v. 6, n. 2, p. 95 – 120, 2012.

SILVA, Amanda Públio (Farmacêutica responsável). Bula de Aloax. 2023. Disponível em: <Microsoft Word – ALOAX_GEL_118610240_VP1.doc (drogariaeconomais.com.br)>. Acessado em 19 maio 2023.

SILVA, Lyane Marque da. Uso de plantas medicinais na comunidade de água branca do Cajari – Amapá. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso de Ciências Biológicas. Instituto de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Amapá. 33 p. 2022.

SILVA, Natalia Cristina Souza et al. A utilização de plantas medicinais e fitoterápicos em prol da saúde. Única Cadernos Acadêmicos, 2017. Disponível em: <http://co.unicaen.com.br:89/periodicos/index.php/UNICA/article/view/56>. Acesso em: 16 maio 2023.

SILVA, Priscila Ewelly Souza da; FURTADO, Clésio de Oliveira, DAMASCENO, Charliana Aragão. Utilização de plantas medicinais e fitoterápicos no Sistema Público de Saúde Brasileiro nos últimos 15 anos: uma revisão integrativa. Brazilian Journal of Development. v. 7, n. 12, p. 116235 – 116255, 2021.

[5] SITINIKI, Rafaela. (Farmacêutica Responsável). Bula de Calendula officinalis. Disponível em: <Calendula officinalis: bula, para que serve e como usar | CR (consultaremedios.com.br)>. Acesso em: 19 maio 2023.

[6] SITINIKI, Rafaela. (Farmacêutica Responsável). Bula do Aloé. Retirado de: Aloe Vera: bula, para que serve e como usar | CR (consultaremedios.com.br). Acesso em: 19 maio 2023.

[7] SITINIKI, Rafaela. (Farmacêutica Responsável). Bula de Espinheira Santo Herbarium. Disponível em: <https://consultaremedios.com.br/espinheira-santa-herbarium/bula>. Acesso em: 20 maio 2023.

[8] SITINIKI, Rafaela. (Farmacêutica Responsável). Bula do Extrato Seco de Salix alba L. Disponível em: <Extrato Seco de Salix Alba L.: bula, para que serve e como usar | CR (consultaremedios.com.br)>. Acesso em: 22 maio 2023.

[9] SITINIKI, Rafaela. (Farmacêutica Responsável). Bula de Garra do Diabo Herbarium. Disponível em: <https://consultaremedios.com.br/garra-do-diabo-herbarium/bula>. Acesso em: 20 maio 2023.

[10] SITINIKI, Rafaela. (Farmacêutica Responsável). Bula do Glycine max (L.) Merr. Disponível em: <Glycine max (L.) Merr.: bula, para que serve e como usar | CR (consultaremedios.com.br)>. Acesso em: 22 maio 2023.

[11] SITINIKI, Rafaela. (Farmacêutica Responsável). Bula do Kronel. Disponível em: <Kronel: bula, para que serve e como usar/CR (consultaremedios.com.br)>. Acesso em: 19 maio 2023.

[12] SITINIKI, Rafaela. (Farmacêutica Responsável). Bula do Matricária chamomilla 1 DH Laboratório Solimões. Disponível em: <Matricária Chamomilla 1DH Laboratório Simões: bula, para que serve e como usar | CR (consultaremedios.com.br)>. Acesso em: 19 maio 2023.

[13] SITINIKI, Rafaela. (Farmacêutica Responsável). Bula de Melissa oficinales. Disponível em: <https://consultaremedios.com.br/melissa-officinalis/bula>. Acesso em: 20 maio 2023.

[14] SITINIKI, Rafaela. (Farmacêutica Responsável). Bula de Mentha piperita. Disponível em: <https://consultaremedios.com.br/mentha-piperita/bula>. Acesso em: 20 maio 2023.

[15] SITINIKI, Rafaela. (Farmacêutica Responsável). Bula de Mikania glomerata. Disponível em: <https://consultaremedios.com.br/mikania-glomerata/bula>. Acesso em: 20 maio 2023.

[16] SITINIKI, Rafaela. (Farmacêutica Responsável). Bula do Plantaben. Disponível em: <Plantaben: bula, para que serve e como usar | CR (consultaremedios.com.br)>. Acesso em: 22 maio 2023.

[17] SITINIKI, Rafaela. (Farmacêutica Responsável). Bula do Plantago ovata piperita. Disponível em: <Plantago ovata: bula, para que serve e como usar | CR (consultaremedios.com.br)>. Acesso em: 22 maio 2023.

[18] SITINIKI, Rafaela. (Farmacêutica Responsável). Bula de Unha de Gato Herbarium. Disponível em: <Unha de Gato Herbarium: bula, para que serve e como usar | CR (consultaremedios.com.br)>. Acesso em: 22 maio 2023.

SOUZA, C. P. M. et al. Utilização de plantas medicinais com atividade antimicrobiana por usuários do serviço público de saúde em Campina Grande – Paraíba. Revista Brasileira de Plantas Medicinais. v. 15, n. 2, p. 188 – 193, 2013.

VEIGA JUNIOR, Valdir F; PINTO, Ângelo C.; MACIEL, Maria Aparecida M. Plantas Medicinais: cura segura?. Química Nova. v, 28, n. 3, p. 519 – 528, 2005.

[1] Advisor. Doctorate. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1613-1331. Currículo Lattes: https://lattes.cnpq.br/1873078781409836.

[2] Doctorate. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009-0003-1056-2840. Currículo Lattes: http://lattes.cnpq.br/2821682713242701.

[3] Master’s Degree. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9698-7780. Currículo Lattes: http://lattes.cnpq.br/90585150692083.

Sent: May 10, 2023.

Approved: June 27, 2023.