REVIEW ARTICLE

RIBEIRO, Andreia Cristina Fonseca [1]

RIBEIRO, Andreia Cristina Fonseca. The importance of art in Xerente indigenous education. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 04, Ed. 06, Vol. 08, p. 55-81. June 2019. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/education/indigenous-education

ABSTRACT

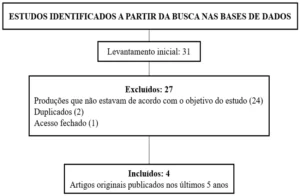

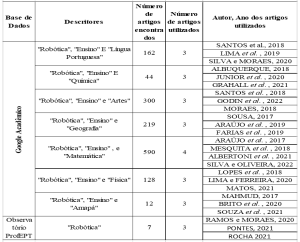

The present work discusses the importance of art in Xerente indigenous education, emphasizing how artistic production is seen either by the Xerente community or by the society that lives. The making of Xerente indigenous art is linked to the cultural root of the artist, but what really marks the art object is the local identity, the culture that it expresses through it. The culture preserved by the community is above all the conservation of its own history, its roots, its daily life. However, time and the social transformations that have taken place make the process difficult and values are gradually being lost, however, working and disseminating indigenous art is a way of keeping the culture of a region alive. Therefore, we highlight the objective of this work: to understand art in education as a form of expression and communication present in all peoples. We carried out the research under the nature of bibliographic research, as it will allow understanding of the meanings and values that come to be configured from the dialogues between the actors: Aracy Lopes Silva (1992), Alfredo Bosi (2001), Jorge Coli (1990) Ana Mae Barbosa (2002), Ulpiano (1983), Darcy Ribeiro (1983) Terezinha de Jesus Maher (2006) and Walter Znini (1983). This research is carried out through readings since it starts from a general formulation of the problem seeking scientific positions that support or deny them, so that in the end the prevalence or not of the listed hypotheses is pointed out.

Keywords: art, indigenous education.

INTRODUCTION

When we think about education in the Tocantins region, we have to reflect on the cultural diversity and plurality that are present in all the municipalities that make up this state.

This article aims to present how Xerente art is important for both the local community and the society in which we are inserted. In this sense, it is a way of preserving their traditional culture and ethnic identity.

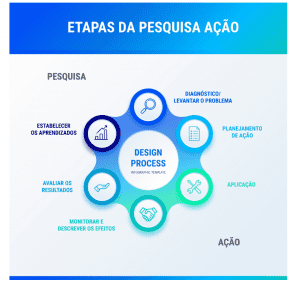

The methodology of this research is constituted both by reading the existing bibliography on the subject and by the fieldwork carried out, observations of the art carried out at the Warã Middle School Center – CEMIX with the participation of teachers dialoguing about the teaching of the arts, in the Salto village . Voice recorder, photo and computer were used.

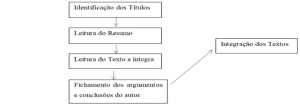

Therefore, some authors contributed to the understanding of the meanings and values that come to be configured from the dialogues between them. I stand out works that were relevant to carry out the research.

Aracy Lopes da Silva and Luis Donizete Benzi Grupioni (1995) launched their work as the title: “The Indigenous Thematic at School: new subsidies for 1st and 2nd grade teachers”, enables teachers and students to critically reflect on the relationship between indigenous peoples and surrounding society.

Alfredo Bosi (2001), his work published under the title: “Reflection on Art”, seeks to show the simplistic and common sense view regarding the conception of art and its implications in the teaching-learning process.

Jorge Coli (1990), without his article published as a title: “What is Art” shows that in a given object it is not more art than the others, just because it was considered through the criteria of a critic.

Ana Mae Barbosa (2002), in her book published under the title: “Disquiet and Changes in Art Teaching” reveals that the educator must be able to create situations that can increase people’s reading and understanding.

Ulpiano Toledo Bezerra Menezes (1983) and Walter Zanini (1983), in their article published under the title: “Art in the Colonial Period”, show the perspectives of the history of indigenous art in its correlations with contemporary conceptions and institutional theories of art. .

Darcy Ribeiro (1983), in his article entitled: “Indigenous Arts and the Definition of Art”, emphasizes Indian art as an activity deeply integrated in life.

Terezinha de Jesus Machado Maher (2006), in her article published under the title: “The Training of Indigenous Teachers: an introductory discussion” brings reflection to educators to rethink their practice, for those who are in the classroom, those in the administrative and managing policies in school education.

The author Odair Giraldin (2000), in his article published under the title: “Body Painting in Akwe Society – Xerente”, presents the patterns of each type of painting, thus showing the sociocultural organization of this society.

And the fundamental participation with regard to Brazilian Legislation such as: National Curricular Parameter – PCN; National Curricular Reference for Indigenous Schools – RCNEI; National Education Plan – PNE and Law Guidelines Bases of National Education – LDBN.

The research developed is divided into three subsections, the first describes the Contextualization of the Research, which means that it explains the location, the target audience, knowing a little about the Xerente indigenous peoples. The second, Indigenous School Education in Brazil, legal aspects and its advances and mismatches. And the third, A Escola e a Arte Xerente, where he describes the structure of the institution, the pedagogical project of the school, the school curriculum and Xerente art reveals the talents and shows the interview of one of the art teachers and her teaching in the classroom. of class.

RESEARCH CONTEXTUALIZATION

The Xerentes call themselves Akwẽ, a term they translate as people, and belong to the Macro-Jê linguistic branch, the Jê family and the Akwẽ language. Its population consists of approximately 2,600 people distributed in more than 50 villages located in the Xerente and Funil Indigenous Lands in a total area of 183,542 hectares, in the municipality of Tocantínia, state of Tocantins (Nolasco, 2010).

The research was carried out in the Salto village, located in the Xerente indigenous land in Tocantínia. It has a semicircle shape, which is the traditional form of the plan of the Akwe villages, but with an opening to its own with the houses arranged around the football field. The opening of the semicircle, however, ended up being closed by the construction of the health post.

There is also a presence of Baptist missionaries, having a temple and a house in the shape of the semicircle of the village for the pastor who attends every weekend. There is still the Xerente Warã High School Center – CEMIX, which is located in a central point of the Xerente territory.

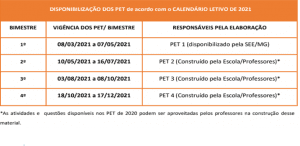

This teaching unit serves elementary school from 6th to 9th year, Integrated Professional High School in Computer Networks, Nursing. There are 08 classes of elementary school, 03 classes of Nursing Technical Course and 03 classes of Computer Network Technical Course.

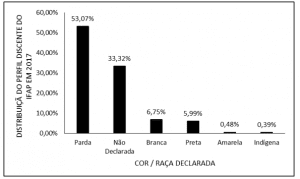

There is a team of teachers, observing that 08 are indigenous and 07 are not indigenous, thus totaling 546 students enrolled.

INDIGENOUS SCHOOL EDUCATION IN BRAZIL

We consider it important to make a brief reflection on Indigenous School Education in Brazil with regard to Brazilian legislation, because currently this term used indicates the teaching that is developed in indigenous schools without a counterpoint to the education developed in the process of traditional and specific socialization for each people. indigenous, but it also guarantees indigenous peoples the right to use their own indigenous teaching and learning processes in schools installed in their villages.

Four determining factors will be commented and mentioned that contributed for the legislation to contemplate a differentiated, specific and intercultural indigenous school education. The first is the Federative Constitution of Brazil of 1988, the second is the Law on National Education Guidelines (Law n. 9394), the third is the National Education Plan (Law n. 10.172) and the fourth is the Opinion n. 99 and Resolution nº3/99 of the National Education Council (CNE).

THE FEDERATIVE CONSTITUTION OF BRAZIL OF 1988

Until 1988, the schooling of indigenous peoples was conducted by the Brazilian State as an instrument that could make the diversity of peoples invisible and strip them of their sociocultural aspects to become non-indigenous. This project of the Brazilian State began to change with the Federal Constitution of 1988, and this became a landmark for the rights of indigenous peoples, contemplating and affirming the right to a differentiated, specific and intercultural education, being written there for the first time. support in the following legislation that deals with Indigenous School Education at the national level.

It is important to emphasize that, through the 1988 Constitution, indigenous peoples in Brazil were assured the right to remain and keep their mother tongues and that their teaching-learning processes were considered in the daily school practice in their villages, thus contributing to the affirmation ethnic and cultural background of these peoples. As we can see in Article 231 of the 1988 Constitution.

São reconhecidos aos índios sua organização social, costumes, línguas, crenças e tradições, e os direitos originários sobre as terras que tradicionalmente ocupam, competindo à União de marcá-las, proteger e fazer respeitar todos os seus bens (BRASIL, 2007, p. 61).

The laws following the Constitution that deal with education, such as the Law of Directives and Bases for National Education and the National Education Plan, have emphasized the right of indigenous peoples to a differentiated education based on the use of indigenous languages, the valorization of knowledge and knowledge of these peoples and for the training of the indigenous themselves to act as teachers in the schools installed in their villages.

The current Brazilian Federal Constitution came into force on October 5, 1988, paving the way to overcome the tradition of Brazilian legislation of seeking social integration and seeing indigenous peoples as a transitory ethnic and social category doomed to disappear and which, therefore, would tend to to become non-indigenous (Freire, 2004).

With the approval of the new constitutional text, the indigenous not only ceased to be considered as an endangered species, but also began to have the right to cultural difference, that is, the right to be peoples with their social and cultural attributes. specific and to remain as such.

The Constitution also recognizes indigenous peoples’ original rights over the land they traditionally occupy or have occupied. Although the ownership of lands occupied by indigenous peoples belongs to the Union, permanent possession is a constitutional right of them, to whom the exclusive use of the wealth existing in them is reserved. Another important innovation of the current Constitution was to guarantee indigenous peoples, their communities and organizations the procedural capacity to go to court in defense of their rights and interests. And, since then, it has become the responsibility of the Union to legislate on indigenous populations in an attempt to protect them.

It is noted that in addition to the recognition of the right to maintain their cultural identities, the 1988 Constitution guarantees them, in Article 210, the use of their mother tongues and their own teaching-learning processes in schools installed in their villages, with the State being responsible for protecting manifestations of indigenous cultures.

Art. 210. Serão fixados conteúdos mínimos para o ensino fundamental, de maneira a assegurar formação básica comum e respeito aos valores culturais e artísticos, nacionais e regionais.

§ 1º O ensino religioso, de matrícula facultativa, constituirá disciplina dos horários normais das escolas públicas de ensino fundamental.

§ 2º O ensino fundamental regular será ministrado em língua portuguesa, assegurada às comunidades indígenas também a utilização de suas línguas maternas e processos próprios de aprendizagem (BRASIL, 2000, p. 58).

Thus, the indigenous school will then be able to play an important and necessary role in the process of self-determination of these peoples. At this point, this right to use the mother tongue and the teaching-learning processes itself presented opportunities for changes in the Law on National Education Guidelines and Bases.

INDIGENOUS SCHOOL EDUCATION IN THE LAW ON GUIDELINES AND BASES FOR NATIONAL EDUCATION – LAW Nº. 9394

The National Education Guidelines and Bases Law (Law No. 9394) was approved by the National Congress in 1996, also known as LDB, Darcy Ribeiro Law, is of fundamental importance because it deals with all education in the country.

The current LDB replaces Law No. 4020/61, which dealt with national education, but at no time did it contemplate indigenous school education. On the other hand, the new LDB clearly mentions school education for indigenous peoples in two moments. The first is in its Article 32, which has been establishing new parameters for Elementary Education, emphasizing that it should be mandatory, lasting nine years, free in public schools, starting at six years of age, with the objective of basic training citizen, through the development of the ability to learn, having as basic means the full mastery of reading, writing and calculation (LDB, 2006).

Therefore, the right inscribed in Article 210 of the Federal Constitution is reproduced here, which ensures the use of indigenous mother tongues in their schooling processes.

O ensino fundamental regular será ministrado em língua portuguesa, assegurada às comunidades indígenas também a utilização de suas línguas maternas e processos próprios de aprendizagem (Artigo 210 da CF).

In another case, Indigenous School Education is included in Articles 78 and 79 of the General and Transitory Provisions Act of the 1988 Constitution. In this context, it is recommended as a duty of the State to offer bilingual and intercultural education in order to contribute to the process of recovery of historical memories of indigenous peoples and reaffirm their identities, also giving them access to the technical-scientific knowledge of national society.

It is then noted that the LDB determines the articulation of education systems for the elaboration of integrated teaching and research programs with the participation of indigenous communities in their formulation and which have the objective of developing cultural curricula corresponding to the respective communities.

O ensino da arte, especialmente em suas expressões regionais, constituirá componente curricular obrigatório nos diversos níveis da educação básica, de forma a promover o desenvolvimento cultural dos alunos (LDB, 2010, p. 93).

Another precept of the LDB makes it possible to put these rights into practice, giving each indigenous school the freedom to define, according to its particularities, its respective pedagogical political project.

Os sistemas de ensino definirão as normas da gestão democrática do ensino público na educação básica, de acordo com as suas peculiaridades e conforme os seguintes princípios:

I – Participação dos profissionais da educação na elaboração do projeto pedagógico da escola;

II – Participação das comunidades escolar e local em conselhos escolares ou equivalentes. (Art. 14. da LDB, 2009, p. 78)

There is another provision in Article 23 that deals with diversity and that allows the school organization to use annual, periodical, semester series, cycles, regular alternation of study periods, non-serial groups or by age criterion.

A educação básica poderá organizar-se em séries anuais, períodos semestrais, ciclos, alternância regular de períodos de estudos, grupos não-seriados, com base na idade, na competência e em outros critérios, ou por forma diversa de organização, sempre que o interesse do processo de aprendizagem assim o recomendar (Art. 23. da LDB, 2009, p. 84).

Likewise, there is talk of the importance of considering the local regional characteristics of society and culture, the economy, the clientele of each school in order to achieve the objectives of Elementary Education. Other devices present in the LDB show the opening of many possibilities so that the school can actually respond to the community’s demand and offer students a teaching-learning process that is more coherent with their realities and with the future projects of their communities.

INDIGENOUS EDUCATION IN THE NATIONAL EDUCATION PLAN

The LDB established in its article 87 that the 10 years following its publication would be considered as “the decade of education”, and also established that the Union should submit to the National Congress a National Education Plan (PNE) with guidelines and goals for these ten years. And so, in mid-2001, the National Education Plan was promulgated, with a chapter that deals with Indigenous School Education that is divided into three parts.

The first part deals with carrying out a diagnosis to identify how school education has been offered to indigenous peoples. And in the second part, the guidelines for Indigenous School Education are presented and, in the last part, there are the objectives and goals that must be achieved in the short and long term.

The National Education Plan emphasizes in its objectives and goals, the universalization of the offer of educational programs to indigenous peoples for all grades of Elementary School, ensuring autonomy for indigenous schools with regard to the creation of their pedagogical projects and in the administration of their financial resources, also guaranteeing the participation of indigenous communities in decisions related to the functioning of these schools.

For this to happen, the plan establishes the need to create the category “indigenous school” to ensure the specificity of the intercultural and bilingual education model and its regularization in the education system.

A União apoiará técnica e financeiramente os sistemas de ensino no provimento da educação intercultural às comunidades indígenas, desenvolvendo programas integrados de ensino e pesquisa.

§ 1º Os programas serão planejados com audiência das comunidades indígenas.

§ 2º Os programas a que se refere este artigo, incluídos nos Planos Nacionais de Educação, terão os seguintes objetivos:

I – Fortalecer as práticas socioculturais e a língua materna de cada comunidade indígena;

II – Manter programas de formação de pessoal especializado, destinado à educação escolar nas comunidades indígenas;

III – desenvolver currículos e programas específicos, neles incluindo os conteúdos culturais correspondentes às respectivas comunidades;

IV – Elaborar e publicar sistematicamente material didático específico e diferenciado (Art. 79 do PNE).

This paved the way for the creation of specific programs to serve indigenous schools, as well as the creation of lines of funding for the implementation of education programs in indigenous areas. And the Union started to organize, together with the states, programs for indigenous school education in Brazil, which should equip indigenous schools with basic didactic resources, including libraries, video libraries and other support materials, as well as adapt existing programs in the Ministry of Education in terms of aiding the development of education.

NATIONAL EDUCATION COUNCIL

The National Council of Education was established in 1996, composed of two chambers: the Chamber of Higher Education and the Chamber of Basic Education, each of which has twelve members appointed by the President of the Republic, with the competence to issue opinions on matters of educational area and on issues related to the application of educational legislation.

After the publication of the Education Guidelines and Bases Law, both Chambers of the National Education Council tried to prepare the necessary norms for the implantation of the new education structure instructed by the legislation.

The National Curriculum Guidelines for Indigenous School Education were established through Opinion No. 14/99, which is divided into two chapters. This opinion presents the rationale for indigenous education, determining the structure and functioning of the indigenous school and proposes more concrete actions in favor of indigenous school education, such as the proposition of the category “indigenous school”, the definition of competencies for the provision of indigenous school education , the training of indigenous teachers, the school curriculum and its flexibility.

THE INSERTION OF ARTS TEACHING IN INDIGENOUS SCHOOL EDUCATION

There is a discussion about the teaching of art or, as understood in school practices, art education. This debate permeates several educational aspects ranging from the professional to the history of art teaching in Brazil.

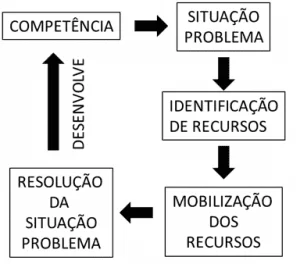

Is it relevant to question what art can do for the formation of individuals beyond education? We understand that everything that is produced by the human being while it is not characteristic of nature, but socially constructed, we note the statement of the author Bosi, who states that “art is construction, it is a doing, art is a set of acts by the which the form is changed, the material offered by nature and culture is transformed” (BOSI, 2001, p. 13)

The aforementioned author presents art using, as references, three actions of reflection: doing, knowing and expressing. Most of the time, they think of art as something consecrated from the past or classic styles and that brings to mind the beautiful, but they forget about art as perceived, regardless of form and style, because “the artist’s view is always a transformation, a combine, a rethinking of the data of sensitive experience” (BOSI, 2001, p. 37).

Art occupies itself in our world through the cultural demonstration that involves objects, the place, the attitudes of admiration. What is considered simple for one society, a utilitarian production can be seen as an erudite production and even an artistic production by another society. The same happens that the work can be analyzed from precious manufacturing criteria such as art in handicrafts, ceramics, golden grass, among others.

For the author Coli (1990), an object is accepted as art and becomes artistic, so this object transmits messages to us. A simple statement that art is not vital, but an element of life.

Uma lâmina num cabo é uma faca, mas é preciso que o cabo seja esculpido e que a lâmina seja gravada, para que seja objeto de um trabalho supérfluo, exprima o amor e a atenção que o homem consagrou a ela (COLI, 1990, p. 87).

Especially because the superfluous becomes essential as a mark of a collectivity, since its meaning was built within the culture. However, reflecting on the process of construction in art in art teaching leads to thinking about how work is carried out in the school space. So this situation goes through the selection of contents to be worked interconnected to the concept of art to be presented.

The path to be followed on the teaching of art, especially with regard to culture, is fragile, since the theoretical currents on the conception of art are diverse and coexist in the school space.

In the school space there are still conflicts regarding the work of art, there are distinctions between the opinions of teachers, students, parents and the community. Thus, the author Barbosa (2002) highlights the changes that have occurred in the teaching of art, especially after the 80s, conceptualizes that:

Arte não é enfeite. Arte é cognição, é profissão, é uma forma diferente de a palavra interpretar o mundo, a realidade, o imaginário e é construído. Como constituído, arte representa o melhor trabalho do ser humano (BARBOSA, 2002, p. 4)

Education should pay more attention to reading, to visual discourse, where the curriculum interacts with cultures, thus enabling the preparation of the public for art, mediating between art and the public, through museums, galleries, cultural spaces, and these should partner with schools so that appreciation by all social segments could be guaranteed.

It is then noted, however, that the contemplation of various indigenous products and artifacts, such as body painting, dance and music, reveals the formal qualities of beauty, balance and formal elaboration that are typical of what we call art.

The author Ulpiano (1983) brings in his texts a fundamental question for the definition of both indigenous art and art in the most traditional sense. And it can happen in a definition of art as an activity that creates a series of objects that will circulate within a certain context, become special in the context of the artist’s studio, the museum, the art gallery, these objects are admired, analyzed, photographed, marketed.

Therefore, the author mentioned above clarifies that among indigenous cultures there is no specific context that defines what is art and what is not, there is no theory of art in the strict sense, that is, among indigenous cultures, there is no there is an “art world” because there is no art as an activity differentiated from the production of useful objects. However, indigenous peoples do not need our theory and art history to support their artistic production. We are the ones who for some reason need to include their artifacts, songs, dance, body painting with their high degree of formal elaboration and their specific cultural meanings in our artistic universe.

The discussion developed in this text has as its starting point the assumption that the world of western art, from the root that seeks to understand the world taking into account only European values, incorporates indigenous products loaded with formal and symbolic qualities to define, justify and replace into perspective our own artistic activity.

Darcy Ribeiro, anthropologist, deals with indigenous art arguing:

O que é arte índia. Com esta expressão designamos certas criações conformadas pelos índios de acordo com os padrões prescritos, geralmente para servir a usos práticos, mas buscando alcançar perfeição (RIBEIRO, 1983, apud ZANINI, 1983, p. 49).

These indigenous artistic expressions come directly from their daily and everyday life, there are no separate objects called beautiful, but creations aimed at formal perfection or simple appreciation giving pride, joy and satisfaction. However, this author understands that the perception of the object of indigenous manufacture is understood as art by the external observer, that is, the anthropologist, the ethnologist and the art historian.

O artista índio não se sabe artista, numa comunidade para qual ele cria sabe o que significa isto que nós consideramos objetos artísticos. O criador indígena é tão somente homem igual aos outros, obrigado como todas as tarefas de subsistência a família, de participação nas durezas e nas alegrias da vida e de desempenho de papéis sociais prescritos de membro da comunidade (RIBEIRO, 1983 apud ZANINI, 1983, p. 50).

The author sees indigenous art as an activity deeply integrated into cultural life without this defining a differentiated and specific sphere of activity or thought.

Art as an area of study is practically unknown in indigenous schools, usually drawings, music, theater are produced, being used as a complementary activity in other areas.

It is worth mentioning that art is linked to the life of all peoples, especially indigenous peoples, among which images, music, dance constitute through expression and communication of ideas and knowledge. Just as language, mathematical knowledge, history, geography or science are part of the areas of the school curriculum, it can also be worked through the contents that are specific to it.

Each artistic modality has its particularities. In the visual arts (drawing, painting, sculpture, engraving) techniques, the preparation of ink, shapes and colors are studied; in the theater the characters, the text, the setting are studied; and in music, rhythms, pitch of sounds, timbre of voice and so on are studied.

Among other aspects, perception, creation, fantasy, imagination, reflection, emotion and feeling are related to artistic productions. In addition to all this, it promotes the development of individual potentialities that are fundamental in the construction of other knowledge.

Understanding art as a form of expression, communication, present in different societies that makes it possible to work on differences benefits students both in personal relationships, in contact with other peoples, thus valuing productions of their own culture. In addition to realizing that human beings have the same abilities to create, express ideas, imagine, be sensitive, have emotions, have the competence to develop techniques and select materials and expand the perception of the world in which we live.

With the emergence of the school and with the contact with non-indigenous people, indigenous peoples began to use paper, pencils, erasers, colored pencils and gouache paint that are used to paint. However, these materials make it possible to develop themes and representations that until then did not appear in their artistic expressions, such as the different ways of representing nature, such as the illustration of mythical narratives, rituals, vegetation, animals and even subjects that relate to the situation of contact with non-indigenous people, airplanes, shotguns, among others.

There is also the drawing of maps that accompany the process of legalization, defense of the territory and that allow the understanding and visualization of the geographic space, the demographic space and the existing riches.

The National Curriculum Framework for Indigenous Schools shows us that the teaching of art taught at school must start from three general objectives, which are “Art, Expression and Knowledge”, “Art and Cultural Plurality” and “Art, Heritage and Identity”.

It is evident that the teacher does not necessarily need to obey this order of the presented sequence, but rather choose among the many suggestions and levels of content offered that best align with the ability to understand and with the performance of students, with their interests and motivations.

In the first objective, which has as its theme “Art, Expression and Knowledge”, it is observed that the student can develop integration with the specific knowledge that involves the different forms of expression and communication of art, exercising their own doing and reflecting on the artistic manifestations of their society and others. In the second objective presented, “Art and Cultural Plurality” allows students to understand the multiplicity of cultural artistic manifestations that exist in different places of various cultures and peoples.

And the third objective, “Art, Heritage and Identity”, makes students reflect on their own identity and that of other social groups, recognizing artistic expressions as an important aspect in the affirmation and expression of identity. This theme focuses on art as a cultural heritage in a perspective of valorization that involves its documentation, preservation and dissemination.

The concern with the development of culture is present in the Law of Directives and Bases of National Education, which establishes in its Article 26, in the second paragraph, that “the teaching of art will constitute a mandatory curricular component, in the different levels of basic education, in a way that promote the cultural development of students”.

The National Curricular Parameters (PCNs), in its sixth volume (Art), guide the work of the Art discipline, presenting it as one of its general objectives.

Compreender e saber identificar a arte como fato histórico contextualizado nas diversas culturas, conhecendo, respeitando e podendo observar as produções presentes no entorno, assim como demais do patrimônio cultural e do universo natural, identificando a existência de diferença nos padrões artísticos e estéticos. (1997, p. 53-54)

The document shows that in the teaching of the arts, the student develops his skills, perception, imagination both when performing artistic forms and in the action of appreciating and knowing the forms produced by him. In the general arts content to be worked on in Elementary School, one of its items presents the diversity of forms of arts and aesthetic conceptions of regional, national and international culture, productions and reproductions and their stories.

Such documents demand and guide that schools offer the discipline of art in their curricula. In the National Curriculum for Indigenous Schools (RCNEI) work suggestions are presented to assist teachers in organizing the curriculum of their schools.

And so, teachers need to daily make choices and make decisions that require planning, recording and evaluation actions. All these decisions end up directing a certain curriculum, that is, giving meaning to the educational experience lived by students and teachers, in their school, at a certain time, and these decisions undergo changes according to the diverse needs that arise in the educational community. . “Before going to the classroom, I always plan what I will work on with my students”, argues a teacher Akwe, here called “Interviewee 1”.

This possibility for the indigenous teacher to plan the contents and the teaching and learning processes is foreseen in the general objectives of the RCNEI, and these should guide curricular decisions,

Valorizar várias produções artísticas presentes nas atividades cotidianas e rituais da comunidade, entendendo suas especificidades em relação as outras produções artísticas.

Refletir sobre o processo de confecção dos objetos de uso cotidiano e ritual como também suas funções, significados e relações com as diferentes situações da vida da comunidade.

Comparar conceitos que envolvem a apreciação das produções artísticas de sua comunidade e de outras culturas (RCNEI, 1998 p. 297).

These three objectives described are related to the thematic axis “Art, Expression and Knowledge”. It is relevant to say that we understand that when developing the content the teacher does not need to obey that sequence, but that he can choose the content to be worked that is in line with the ability to absorb and the performance of the students, through their interests and motivated by the educator.

Compreender a importância da arte como uma manifestação presente em todos os povos e culturas, de diferentes tempos e lugares;

Reconhecer o valor da arte e da cultura das minorias étnicas e sociais existente no Brasil e em outros países.

Valorizar a produção artística pessoal, a partir do contato com as produções de crianças e jovens de outras culturas (RCNEI, 1998, p. 305).

The four objectives mentioned above are related to the thematic axis Art and Cultural Plurality, this makes students understand the diversity of cultural artistic manifestations that exist in various parts of the world, as well as aspects that differentiate and bring together different cultures and peoples.

In this sense, art history studies, whose knowledge may have as a starting point the reality of students or other indigenous cultures, can be worked without worrying about time, but rather valuing what is being produced, art.

“valorizar e defender seu patrimônio artístico e cultural reconhecendo como parto do patrimônio nacional e universal;

Compreender as produções artísticas de sua sociedade e de outras como elementos que propiciam identidade étnica;

Compreender as expressões artísticas de sua sociedade e de outras, enquanto patrimônio culturais que devem ser preservados, valorizados, preservados, valorizados, documentados e divulgado”. (RCNEI, p. 308)

The three objectives presented above are related to the thematic axis “Art, Heritage and Identity”, and, in this case, students can reflect on their own identity and that of other social groups, recognizing artistic expression as an important aspect in the affirmation and expression of identity.

GETTING TO KNOW THE STRUCTURE OF THE WARÃ HIGH SCHOOL CENTER – CEMIX

This teaching unit serves a clientele of elementary education in the final grades and vocational technical education in computer networks and nursing.

Observing the school environment, it has 14 classrooms, 01 director’s room, 01 teachers’ room, 01 computer lab, 01 covered sports court, 01 kitchen, 01 pantry, 01 secretariat room, 01 warehouse, 01 covered patio, 02 bathrooms. With technological equipment such as: 03 computers, 01 printer, 01 stereo, 11 computers for students, 01 TV, 01 copier.

The pedagogical team is composed of director João Kawanha Xerente, taking into account that the pedagogical coordinators are indigenous and trained in the field of education and are part of the School Council of this institution.

The members of the School Council meet monthly to discuss the administration of the financial resource, as the school receives funding from the federal resource and from the Integrated High School Program – ProEMI.

In the team of teachers there are 15 professionals, 08 indigenous and 07 non-indigenous, most of whom have higher education. There is a rapport and partnership between them.

During the period he was with these educators, he noticed the concern to do the best, even though the pedagogical materials are so restricted, he always had the collaboration of the teachers themselves to carry out projects. There are also complementary activities such as: School Support in Reading and Text Production; capoeira; School Garden; Gymnastics and Table Tennis.

THE PEDAGOGICAL POLITICAL PROJECT

It is known that this document is the instrument that allows the indigenous community to express which school they want, how it should meet their interests, how it should be structured, and how it integrates into life and their community projects.

That is why it is important to highlight some points that are indispensable, such as: the need to ensure the rights to differentiated education for indigenous peoples and the valorization of their language, knowledge and their own pedagogical process; it must reflect their way of life, the cultural and political conception of each indigenous people.

There is a concern on the part of the management team regarding the political pedagogical project of the school, as the participation of the school and local community is minimal, usually it is carried out only between teachers, coordination and direction.

It has always sought to incorporate Afro-Brazilian and indigenous education, especially in the areas of arts, literature and history.

Another aspect that teachers have discussed among the group is the importance of teaching music, rituals, valuing identity.

One of the points that has made a difference, regarding school meals, as it has incorporated nutrition, thus developing healthy practices in accordance with the guidelines of the PNAE – National School Feeding Program.

It is worth noting that the pedagogical coordination has encouraged and dialogued with teachers the importance of always using the general national curriculum guidelines for basic education, whether for planning or in the elaboration of the Pedagogical Political Project.

The teacher of this teaching unit has not been waiting for resources to arrive, whether they are to be used in the pedagogical area or in administration in view of the needs that exist, but the entire team has made an effort to work on what has what is offered because the challenges have been very great. .

THE SCHOOL CURRICULUM

It is relevant to consider this theme, because we know that the teaching and learning of our students flows through it.

Talk and discuss ideas that contribute to the realization of the community autonomy project from its history to develop new strategies of cultural physical survival, with social life, with its daily and extraordinary events, becoming an important factor of influence in the selection of the school curriculum.

A collective fishing, as part of physical education, the opening of a clearing, for school feeding; clearing land around the school; building a fruit tree nursery and so on. Such events are part of school knowledge and community life, opening the doors to the classroom and giving social and community meaning to the school.

Therefore, in this way, we have a certain curriculum that has organized and given direction to the educational experience lived by students, teachers and all who are part of it, in a period of time, and these ideas may undergo changes according to the diverse needs that arise in the educational community. .

However, the curriculum is a program of work done during the term and that can be changed as the students learn.

THE XERENTE ART

It is not an ordinary day for the students of the Warã Middle School – CEMIX, as they are all dressed in uniform, even sometimes without power, the heat is great in the classroom, but they are happy and participative, the faces marked by their identity of the people, genipap and charcoal painting, Indian week: Ethnic Mathematics Fair. But it’s not just about math, but about the colors, the embellishments and adornments that women use to explore their art.

What exists in a striking way are the rules for the production of objects, the ways to guarantee the technical quality of the execution, the choice of raw material, the maintenance of shapes and dimensions, materials and colors. Being that in the Xerente people, creativity is not encouraged, nor are they obliged to inventions, but on the contrary, the maintenance of tradition is valued.

Now the school has a greater participation of indigenous people, many of them chased their dream, went to Goiânia to seek knowledge to help their people. “I want to be a teacher” says interviewee 1, graduated in Intercultural Education at the Federal University of Goiás – UFG.

Because since 1984 she began her career as a classroom teacher, teaching her mother tongue, teaching those students in her community to read and write. And she had the opportunity to help in several villages such as: Brejinho, Rio do Sono, Baixa Funda, Serrinha and started at CEMIX in 2006.

“I was the first indigenous woman teacher at that time, because women had no power and today everyone is looking for the same dream” says interviewee 1.

And she made it clear that even when she noticed that the student reached the end of the year, and realized that she had not learned to read and write, she did not pass the year, because she always understood that education is a great responsibility of the teacher.

“There were great challenges in my life, because I spent many years as an art teacher, as I didn’t have teaching materials such as: gouache paint, scissors, cardboard, colored pencils, glue and others, I had to think fast to carry out the activity and not frustrate my students. So I decided that I would use our rituals, dances, decorations as a way of showing the art and valuing what we have.” Says interviewee 1.

She argued that, throughout her 22-year career as a teacher, she always had everything planned before starting her class and, if she did not have the pedagogical material, she would use the resources she had, to prevent her students from getting frustrated or giving up on studying. .

“I had a moment that I can’t forget because I had a lot of ideas, but I didn’t have any teaching material, I thought then why not make a crown out of the old toucans’ feathers, their feathers are yellow with red on top. This too is an art. Says interviewee 1.

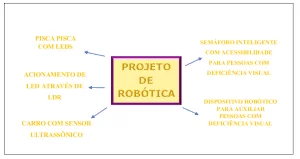

Among the Akwe, art is experienced since childhood, because through rituals there is a presence of art, which is also in the manual work for making objects with golden grass, and that these expressions of Akwe art are used by her in the classroom. The art discipline has the participation of two teachers who work with elementary and integrated high schools.

We know that art is a product of human creativity, the result of their life experience, their vision of the world. The way of seeing oneself, others, nature, spirits. They belong to a dynamic and differentiated culture across the planet from ancient times to the present day.

Human beings produce art as symbolism, beauty, representation of their feelings and values.

The more we broaden our view of the world, the more life experience, the better we can express our feelings using art.

By carefully observing everything around us, we realize that life is art in gesture, colors, sounds, rhythms and emotions that can make us feel like or different from others.

The best way to learn about art is to think about everything we experience, feel and observe.

And so, given the diversity of Akwe cultural aspects, we first describe and analyze the production of objects for everyday and decorative use, with the permanence of their production processes being ensured by the transmission to new generations, whose learning begins in childhood. and continues to old age. On this point Maher (2006) tells us that,

Uma característica que chama a atenção na Educação Indígena tradicional é o fato de, nesse tipo de educação, o ensino e a aprendizagem ocorrerem de forma continuada, sem que haja cortes abruptos nas atividades do cotidiano. Entre nós, o ensino e a aprendizagem se dão em momentos e contextos muito específicos: “Está na hora de levar meu filho para a escola para que ele possa ser alfabetizado”; “Minha filha está fazendo um curso, em uma escola de informática, das 4:00 às 5:30 da tarde”. Nas sociedades indígenas, o ensinar e o aprender são ações mescladas, incorporadas a rotina do dia a dia, ao trabalho e ao lazer e não estão restritas a nenhum espaço específico. A escola é todo espaço físico da comunidade. Ensina-se a pescar no rio evidentemente. Ensina a plantar no roçado. Para aprender, para ensinar, qualquer lugar é lugar, qualquer hora é hora (MAHER, 2006, p. 17).

It is relevant to say that this activity, of producing objects, in the past was practiced by the indigenous people to be used as adornments and/or as household items, however, nowadays this activity is also conceived as one of the indigenous means of subsistence.

Thus, we chose to describe two types of production, one having golden grass as the base of its raw material, and the other having buriti straw as raw material. The cofo, for example, is made with the green buriti straw composed of several leaves. These are symmetrically intertwined and, as the person begins to trace them, they begin to form a singular object in a round, rectangular and/or oval shape, depending on the need for its use by the indigenous person.

It can be made by men or women and can be used to store food, clothes, transport game, fish or food harvested in the forest, such as fruits. It is very common to find an indigenous person going from one village to another or going to or coming from the city carrying his cofo, which is a basket used to store or transport products and objects. We emphasize that the dimensions of the cofos are the most varied, depending in part on their need for use.

The production of objects using golden grass as a raw material is materialized in hats, bags, necklaces, earrings, bracelets and baskets. These are used by the indigenous people as adornments in their traditional festivals, or sold in the local commerce of the cities of Tocantínia, Miracema do Tocantins and Palmas, the same happens with the handicrafts made of buriti fiber or straw.

The objects produced by the Xerente, in addition to being useful in culture, represent different ways of looking at the indigenous being, on the changes that have been taking place within the community, however, they do not omit them in expressing their different forms of organization that take as a reference. cosmology, creation and manifestation myths. Thus, they create and recreate the dynamics of each new Xerente generation, through individuals who daily experience their own knowledge and actions in direct contact with nature, with beings\animals and with the natural elements that complement them.

This production process, which uses golden grass as its raw material, is a novelty among the Xerente. Such raw material has always existed in their lands, but in the past they used buriti fibers, which went through a tanning and softening process, these were sewn in such a way as to form the objects.

In the struggle for the preservation of traditional knowledge, many indigenous people still seek to keep some traces alive, so it is customary to find some indigenous (older) making their objects with buriti fiber.

Analyzing the two types of production described above, we noticed that the process with buriti straw or fiber still preserves more traditional elements, while manual work with golden grass, due to direct contact with non-indigenous people, started to incorporate the so-called fad in the process. with the introduction of decorative objects, such as sewing with golden or silver threads, use of buttons, gemstones and beads.

We note in this context that the use of these modified objects took place from the moment the handicrafts began to be marketed and, consequently, began to meet the demands of buyers in their manufacture.

However, in this bulge of activities of cultural and traditional manifestation, we have body painting, which is a symbology of identification of the indigenous people as members belonging to one of the moieties, Doĩ or Wahirê, which still remains with vitality among the indigenous people, even with constant contact with non-indigenous society.

In his monograph, Agenor Farias (1990), suggests that from the affiliation to the exogamous moieties and, consequently, to their respective patrilineal clans, the Xerente build the basis of their society and that these institutions are, today, among the most fundamental since they locate the individual at the village level and at the broader level of Xerente society as a whole. For him, the vitality of these institutions would be particularly demonstrated, on the one hand, through body language: the clan affiliations and, consequently, the exogamous moieties, would be identifiable through the visibility provided by the variation of the basic motifs – circle/Doi; trace/Wahirê – of body painting practiced in ritual moments. In this way, the Doi moiety serves as a generic designation for the set of clans whose specific patterns of body painting are based on the circle and Wahirê, all clans that have their characteristic motif in the trait.

Aracy Lopes da Silva and Agenor Farias (1992) were among the Akwẽ-Xerente in the 1980s, and observed that many of the aspects of the Xerente social organization presented by Nimuendajú, and not observed by Maybury-Lewis, such as the vitality of the exogamy of the moieties19 , the clan identification apprehended by the authors through body painting, and the continuity of the masculine association system, are in force quite clearly.

The art represented by literature, drawing, painting, artifacts, music, dances, crafts, although present in all human cultures, is evidenced in indigenous cultures. It realizes that it is still poorly developed in school contents and practices.

We recognize that knowledge and appreciation of artistic expression stimulate human creativity in its broadest dimensions. And the themes that were selected related to culture, traditional narratives, languages and indigenous stories.

Theoretical texts, works of literature, papers, music, technical information, documentaries regarding the themes, and pedagogical materials have been made available to the students. Most of their activities were developed through their experience and experience related to their culture, but bringing discussions, storytelling, writing and text rewriting, reading the record of memories of the elderly who started to compose a collection of teaching materials.

In this sense, we understand the presence of art, the experiences and experiences of children in the indigenous school to be extremely relevant, since it is expressed in different languages, is part of their daily lives and makes up a wide repertoire of children’s knowledge. For this reason, the more knowledge and understanding indigenous and non-Indian pedagogues, directors, teachers have about the role of art in the process of creation and school learning, the greater commitment they can have and the more the school will be in a position to develop work that favors traditional knowledge, creativity, collective learning, reflection, feelings and children’s participation in their school learning process.

Traditionally, art is part of the work, the production of the life of human groups, being experienced and experienced by all, evidencing fundamental social elements, processes and complex structures with beauty and expressiveness that can only be understood through aesthetic perception.

In this process, adult mediation is essential for children’s learning. By participating in the life of their social group, the child comes to know and appropriate what was produced by past generations and this allows them to develop, understand and act in the world that surrounds them, providing them with instruments to interact intensely and critically.

Through language the human being performs abstractions, generalizations, communicates, names and systematizes. These actions promote qualitative leaps in the organization and explanation of the world, acting dynamically in the formation of human consciousness. In this sense, the word, gestures, attitudes, body movements work, from an early age, as mediating and interchange elements between the adult and the child. Communicating with members of his sociocultural group, the child accesses elements of the surrounding environment and uses it.

Art, as an important human language, has great significance in learning. It consists of the anthropomorphized reflection of reality, being an activity that starts from human life and can contribute to a true knowledge of human beings and society.

Art is thus a form of expression of the concrete reality in which one lives and favors knowledge in a special way, since it works with aesthetic reflection, imagination, feeling, beauty and creation.

It is essential that the school observes these issues that permeate the daily life of indigenous communities today, providing opportunities for dialogues and practices that have meaning in the different lived contexts and developing actions that effectively involve children, as a means of contributing to their learning and physical development, emotional, aesthetic and intellectual.

It is possible to say that art has several areas and possibilities for school actions, but it is essential for mediators/teachers that they have a broad training to better organize such work and not run the risk of reducing art to a hobby, as a way of maintaining busy children, or even as a “bridge” to alphabetic writing. It is necessary to understand the depth and meaning of different artistic expressions in teaching and learning.

Art as a language is essential in indigenous school education, since it is part of the history and life of these peoples, with a lot of emphasis on the daily lives of ethnic groups.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

This research allowed us to observe how the Tocantins State Department of Education needs to have a closer relationship with the Wara high school center – Cemix, located in the Xerentes lands, Aldeia Salto, because even though it was created a few years ago, one can see the lack of having this support both in the physical structure and in the pedagogical aspect.

This art teacher so splendidly reveals his courage to succeed in life in the face of dialogue, he shows the difficulties they faced in studying. They had to go to the State of Goiás, leaving their families and facing inclusion in the non-indigenous society, learning new cultures, breaking the obstacles of fear and financial difficulties to stay and complete their studies, all for the benefit of their people and their community.

It is important to highlight that the financial resources used in indigenous education are below the needs. In order to respond with quality to the complexity involved in the formulation and execution of a pedagogical proposal that respects indigenous logics and pluricultural contexts that guarantee the participation of indigenous communities and their leaders, it is necessary to make sufficient human and financial resources available.

There is a lack of specific government resources to satisfactorily meet the functioning of teaching programs aimed at training indigenous professionals, despite the great progress we have made in terms of differentiated school education, there is still a long way to go.

Despite the constant and difficult struggle, we are constantly faced with disrespect, total lack of information and neglect of government officials about the real needs and rights to intercultural and quality education that allows us to fully participate in Brazilian citizens with our cultural differences assured.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

BARBOSA, A.M. Inquietações e Mudanças no Ensino da Arte – São Paulo: Cortez, 2002;

BOSI, A. Reflexões sobre a Arte. 7ª Edição. São Paulo: Ática, 2001;

BRASIL. LEI nº 9.394, de 20 de Dezembro de 1.996. Lei Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional, Brasília, DF: Senado, 1996;

________, Plano Nacional de Educação. Assembleia Legislativa, 2003;

________, Parâmetros Curriculares Nacionais: Arte/Secretaria de Educação Fundamental, Brasília: MEC/SEF;

________, Referencial Curricular Nacional para Escola Indígena. Ministério da Educação e Desporto, Secretaria de Educação Fundiária – Brasília: MEC/SEF, 1998;

CALI, J. O que é Arte? Brasília: Brasiliense, 1990;

MAHER, T. M. Formação de Professores Indígenas: uma discussão introdutória. Campinas: Editora Mercado de Letras, 2006. In: GRUPIONI, L.D.B. Formação de professores indígenas: repensando trajetórias.

ULPIANO, B.M. A Arte no Período Colonial, Pré-Colonial In ZANINI, Walter (Org). História Geral da Arte no Brasil – V.I. São Paulo: Instituto Walther Moreira Salles. 1983;

SILVA, A.L. e GRUPIONI, L.D. (Orgs). A Temática Indígena na Escola: novos subsídios para professores de 1º e 2º graus. Brasília: MEC/MARI/UNESCO, 1995.

[1] Master’s Student in Academic Education – UFT; Specialist in School Pedagogy – IBPEX and graduated in Pedagogy in Full Degree – UNITINS.

Sent: April, 2018.

Approved: June, 2019.