ORIGINAL ARTICLE

PEREIRA, Jamilli Santos Martins [1], OLIVEIRA, Cleber Macedo de [2], FECURY, Amanda Alves [3], DENDASCK, Carla Viana [4], DIAS, Claudio Alberto Gellis de Mattos [5]

PEREIRA, Jamilli Santos Martins. et al. Indigenous formal education within the scope of Professional and Technological Education (EPT). Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year. 07, Ed. 01, Vol. 05, pp. 47-59. January 2022. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/education/indigenous-formal-education, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/education/indigenous-formal-education

ABSTRACT

Education can mean the link between non-Indigenous people and indigenous people. Law 12,711/2012 deals with the obligation to reserve places in federal universities and institutes, combining public school attendance with income and ethnicity. The construction of professional education courses integrated with indigenous school education must consider the impasses, as well as the potentialities, in the relationship between indigenous knowledge and practices and technical-scientific knowledge, as well as the possibility that indigenous peoples will actually enroll in them your own perspective. The aim of this paper is to discuss formal indigenous education within the scope of Professional and Technological Education (EPT)[6]. For that, a bibliographic research was carried out in Portuguese in databases. Education seems to be the path for the integration of indigenous people and their formation for their own benefit and that of the community. The policy of quotas or affirmative actions is an attempt to reduce the social distance when it comes to access to places in education, including technical ones. The existence of centers of Afro-Brazilian and indigenous studies seems, albeit timidly, to contribute to research and dissemination on ethnic-racial identities and relations, aiming at reducing socio-educational distance and differences within institutions. Despite the preparation, even if under construction, of institutions to serve a diverse public such as indigenous people, their access is still considered small.

Keywords: Teaching, EPT, Indigenous Education, IFAP.

INTRODUCTION

Education can mean the link between non-indigenous people and indigenous people in a search for space, not in the form of war, but as a guarantee of resistance and appreciation.

O problema indígena não pode ser compreendido fora dos quadros da sociedade brasileira, mesmo porque só existe onde e quando índio e não-índio entram em contato. É, pois, um problema de interação entre etnias tribais e a sociedade nacional (RIBEIRO, 1989).

For Darcy Ribeiro, education is a great ally in the process of formation and recognition of the indigenous people, an education in which the student sees himself and can change his context, an aid, a gradual participation with the rest of his indigenous community.

Em se tratando de povos indígenas no Brasil, observa-se que o contato dos nativos com os colonizadores europeus transformou a forma de esses povos conceberem sua educação. Hoje a educação formal e a educação informal são realizadas paralelamente e quase com igual importância dentro de muitas comunidades indígenas, sobretudo dentro daquelas que mantém maior contato com não-indígenas (QUARESMA e FERREIRA, 2013).

PATHS TAKEN BY INDIGENOUS EDUCATION IN BRAZIL

Many wars and battles were fought, as the indigenous people were resistant to the Jesuits’ schooling and thus indigenous school education began to materialize only after 1945 (MENDES et al., 2017).

With the advent of the Federal Constitution (FC) of 1988, indigenous school education turned to objectives such as: preserving the historicity, ethnicity and culture of indigenous peoples (BRASIL, 1988). Thus, the Union became responsible for offering and ensuring quality indigenous school education and safeguarding their culture, social organization, customs, languages, beliefs, traditions and the original rights over their lands, as well as the application of specific learning methodologies for the indigenous populations (MENDES et al., 2017).

Seven years after the promulgation of the Federal Constitution, the law of guidelines and bases of national education (LDB)[7] was published, using the term indigenous school education, based on social equality, bilingualism, interculturality, historicity of a people, in the preservation of the language maternal, ethnic appreciation and their sciences and guarantee to these communities access to information and technical-scientific knowledge of national and international society, indigenous and non-indigenous (BRASIL, 1996). The LDB ratifies some rights guaranteed in the Federal Constitution of 1988 as presented in the constitution, article 210: “§ 2nd Regular elementary education will be taught in Portuguese, ensuring indigenous communities also the use of their mother tongues and their own learning processes” (BRASIL, 1988).

In 1999, the first National Curriculum Guidelines for Indigenous School Education were instituted, which established norms for the functioning of indigenous basic education, definition and competence for offer, also dealt with the formation of indigenous teachers, curriculum, flexibility and pedagogical and curricular freedom (BRASIL , 1999).

Later, in 2001, the National Education Plan (PNE)[8], with its objectives and goals, granted the states competence for indigenous school education and had as its objectives the cooperation of indigenous peoples in the decisions of their schools and freedom in the construction of their political project pedagogical, thus creating the category Indigenous School (BRASIL, 2001).

In 2012, Law No. 12,711/12 was approved, one of the public policies used to reduce and confront ethnic-racial inequalities. This law also establishes measures to expand the access of the poorest segments, blacks and indigenous people to universities linked to the Ministry of Education and federal institutions of secondary technical education (BRASIL, 2012).

Still in accordance with the quota law, as Law No. 12,711/12 is popularly called, federal institutions of higher education must reserve at least 50% of their vacancies for students who studied high school in public schools and of this percentage, 50% of the vacancies must be reserved for students with per capita family income up to a maximum of one and a half minimum wages. Article 4 of the law stipulates that federal institutions of secondary technical education must reserve 50% of their vacancies in each entrance selection for students who studied elementary education in public schools. These vacancies must be filled by self-declared blacks, browns, indigenous peoples and people with disabilities, with a minimum total of vacancies with the same proportion of the population of these minorities in the federative unit where the institution is located, according to the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics/ IBGE[9] (BRASIL, 2012).

THE FEDERAL NETWORK

The Federal Network of Professional, Scientific and Technological Education was created in 1909 by the then President of the Republic, Nilo Peçanha, through Decree nº 7566/1909:

Considerando: que o aumento constante da população das cidades exige que se facilite às classes proletárias os meios de vencer as dificuldades sempre crescentes da luta pela existência: que para isso se torna necessário, não só habilitar os filhos dos desfavorecidos da fortuna com o indispensável preparo técnico e intelectual, como faze-los adquirir hábitos de trabalho profícuo, que os afastara da ociosidade ignorante, escola do vício e do crime; Que é um dos primeiros deveres do Governo da Republica formar cidadãos uteis a Nação: Decreta: Art. 1º Em cada uma das capitais dos Estados da Republica o Governo Federal manterá, por intermédio do Ministério da Agricultura, Industria e Commercio uma Escola de Aprendizes Artífices, destinada ao ensino profissional primário e gratuito (BRASIL, 2020).

By the aforementioned decree, 19 schools for Apprentices and Craftsmen were created, which later became the first Federal Centers for Professional and Technological Education (CEFETs)[10] (BRASIL, 2020).

On December 29, 2008, Law nº. 11.892/08, which transforms Federal Centers for Professional and Technological Education (CEFETs), Decentralized Teaching Units (UNEDs)[11], agrotechnical schools and federal technical schools, as well as schools linked to universities into the Federal Institutes of Education, Science and Technology. Federal institutes are institutions of basic, professional and technological education, multi-curricular and multi-campi. They offer professional and technological education in various teaching modalities, combining technical and technological knowledge, training and targeting professionals in various areas of the economy, with emphasis on economic and social, regional and national development (BRASIL, 2008).

In 2020, the federal network reached more than one million enrolled students and 80,000 civil servants. It comprises 38 Federal Institutes of Education, Science and Technology (IFs), Two Federal Centers for Technological Education (Cefets); Pedro II College; A Federal Technological University; and 23 Technical Schools Linked to Federal Universities. The institutions with their respective campuses total 661 campuses, distributed throughout the national territory (IFFAR, 2021).

The expansion process of Professional and Technological Education (EPT) has gone through transformations, reconfigurations and institutional incorporations. They make up a program that, despite being criticized for associating it with economicist ideas, has brought considerable and visible benefits to the society where it operates. This growth is dependent on public policies for education and the weaknesses of the political scenario (SOUZA and SILVA, 2016).

OBJECTIVE

Discuss formal indigenous education within the scope of Professional and Technological Education (EPT).

METHOD

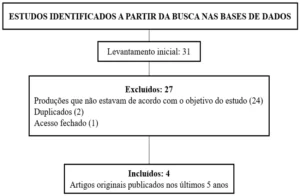

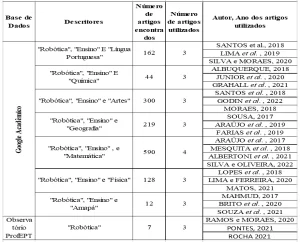

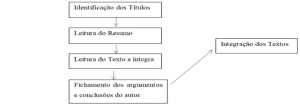

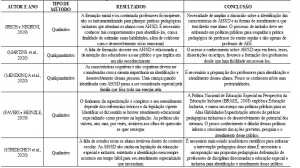

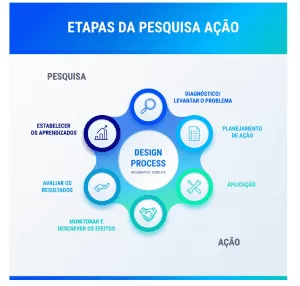

A bibliographic research was carried out in Portuguese in research databases such as Scientific Electronic Library Online – SciELO; Academic Google; Brazilian Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations – BDTD; and journals CAPES (Portal da CAPES).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

THE QUOTA POLICY FOR ACCESS TO EDUCATION

Law 12,711/2012 deals with the obligation to reserve vacancies in federal universities and institutes, combining public school attendance with income and ethnicity (BRASIL, 2012). Its main objective is to promote access to quality and free education in federal institutions of secondary and higher level technical education to layers of society that, in the past, did not have opportunities (WANDROSKI and COLEN, 2014). Also defined as an affirmative action policy, the quota system is used as a promotional strategy, in order to encourage the inclusion of vulnerable groups, and provide reparation, distributive justice and diversity. Affirmative actions can be classified as public and private policies. The first stems from actions by the executive or judiciary and actions aimed at combating discrimination established by the private sector (TORRES et al., 2021).

In a historical context of affirmative policies, used as support for actions in Brazil, like the North American system, it is justified by a similar history of exploitation by European colonies and use of slaves (WANDROSKI and COLEN, 2014). In India, reference is made to the vacancy system for Dalits, the so-called “untouchables”, the most discriminated against group in the country. It is the largest system ever devised, inspiring many countries, building equality from difference. Other countries also developed affirmative actions, as well as: Malaysia, Australia, Canada, Nigeria, South Africa, Argentina, Cuba (MOEHLECKE, 2002).

Brazilian society (multi-ethnic, with indigenous, white, black and other ethnicities) must be represented in the decision and implementation of educational public policies. The participation of social movements is an important element for the construction of these policies, with indigenous peoples being part of one of the segments that most demand from the State actions aimed at the construction of these policies. The implementation of this access must consider sociocultural, political, demographic differences and, most importantly, their own education processes (BANIWA, 2013).

In this sense, it is important to mention that even though the quota policy has been a positive response, its implementation has generated controversial issues. The first issue is that it refers to indigenous rights as collective (where the community is the individual). Educational institutions consider the right to admission on an individual basis, which is considered a risk or threat to their principles and ways of life. This group is responsible for choosing candidates and courses of interest, as well as monitoring training and providing feedback to the community. However, what is observed, for the most part, are indigenous individuals residing in urban centers who are not committed to the community benefiting from the current policy. The situation is aggravated by the complexity of access to entrance exams and entrance exams. It would be necessary to attend, in the same proportion, the indigenous people who live in the communities, as they are more likely to maintain the commitment to return to it after finishing the course (BANIWA, 2013).

There are challenges faced by indigenous students in the face of formal education. It is important to consider the importance of leveling knowledge and adapting it to the academic world. This brings the need for monitoring and mentoring programs to assist them from access to completion of courses, in order to reduce dropout (SOUZA et al., 2020). Providing quotas is not enough. It is also a priority to subsidize projects and programs, as well as to make possible research grants that preserve the individual’s connection with his community. It then becomes interesting to also provide pedagogical actions with the aim of reducing the discrimination faced by these students (BANIWA, 2013).

The quota law represents a significant, albeit modest, step towards inclusion and democratization of access and permanence in education. In order to understand the reality of this process, it is important to present the context and the consequences of the vacancy reservation policy (KOSTRYCKI, 2020).

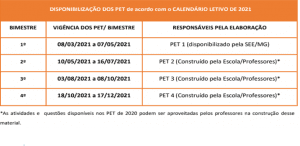

QUOTA POLICY AND THE INSTITUTO FEDERAL DO AMAPÁ (IFAP)

The Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Amapá was created by Law nº 11.892/2008, the same law that established the Federal Network of Professional, Scientific and Technological Education, from the Escola Técnica Federal do Amapá (ETFAP), established by Law No. 11,534, of October 25, 2007 (RAMOFLY and MACEDO, 2020). It started its activities in 2010, with the Macapá and Laranjal do Jari units, offering technical courses in the Subsequent modality, providing 420 vacancies (MIRANDA, 2021).

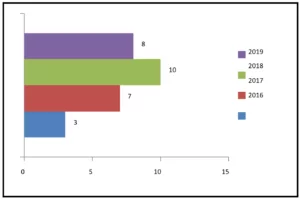

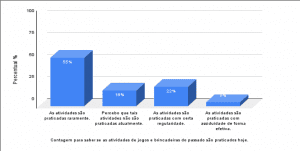

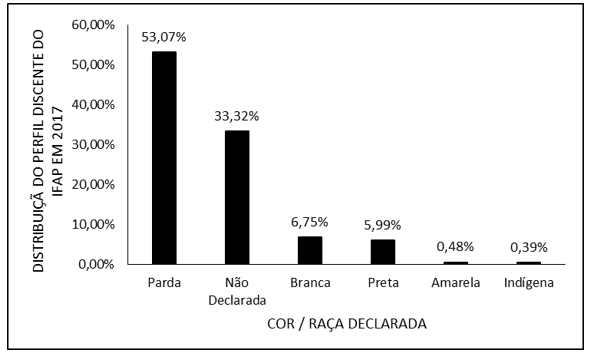

The Institutional Development Plan (PDI)[12] 2010-2014, guided by affirmative actions, in compliance with law 12,711/2012, on the implementation of quotas, had 10% of vacancies allocated to quotas for blacks and indigenous people (IFAP, 2012). The graph exemplifies the distribution of the IFAP student profile, by color/race, in the year 2017.

Graph 1: Distribution of IFAP student profile, by color/race, in 2017

In its 2019 PDI, IFAP is committed, by 2023, to increasing the percentage of places allocated to students from public, indigenous and quilombola schools in its selection process (IFAP, 2019a).

Currently, the Instituto Federal do Amapá, in its selection process notices, reserves 50% of its vacancies for quotas (IFAP, 2021). Vacancies are provided as a reserve of vacancies and not guarantee. The student must meet the requirements for the vacancy and have the supporting documents to qualify for the vacancy (KOSTRYCKI, 2020). The selection process for integrated courses, for example, is carried out via document analysis (IFAP, 2021).

Candidates who go through all the stages face another challenge, staying at the institution and finishing the course, these represent the other students who did not have the opportunity to access. It is up to the institution to promote conditions for permanence and successful exit (KOSTRYCKI, 2020).

AFRO-BRAZILIAN AND INDIGENOUS STUDIES CENTER – NEABI/IFAP

The Afro-Brazilian and Indigenous Studies Center – NEABI/IFAP[13]

has a propositional, consultative nature, linked to the Dean of Extension, Research, Graduate Studies and Innovation. It has the function of assisting in directing studies, stimulating and promoting teaching, research and extension actions that promote reflection on the themes of identities and ethnic-racial relations, referring to issues of diversity in the perspective of multicultural principles, having as scope the promotion of studies and development of actions to value Afro and indigenous identities, within the scope of the institution and in its relations with the external community (IFAP, 2019b).

THE INDIGENOUS IN THE FIELD OF PROFESSIONAL AND TECHNOLOGICAL EDUCATION

The construction of professional education courses integrated with indigenous school education must consider the impasses, as well as the potentialities, in the relationship between indigenous knowledge and practices and technical-scientific knowledge, as well as the possibility that indigenous peoples will actually enroll in them their own perspective (BRASIL, 2007).

For SANTOS and MÜLLING (2019), the problem lies in knowing with what ethnic relation the workforce is being technified, when the objective of eliminating hunger is in a modern attitude that is useful and profitable, economic and divorced from an internal and cultural ethics, of an ethnic and sustainable and strengthened collective project. Since, once the constitutional right to the processes of indigenous existence is recognized, their resistance to insertion in the capitalist world is legitimate, legitimizing their struggle to walk in the construction of alternative spaces to the current universalist system.

Sua reexistência trata-se da reconfiguração da vida indígena em diálogo com o mundo, do movimento do que é mutável e imutável na cultura, sob a perspectiva de seus sujeitos. Além disso, não se trata meramente de pedir acesso às vantagens dos avanços do ocidente mediante acesso à educação, nem de demonstrar que a sabedoria indígena detém também caráter científico, mas de demarcar a vigência das culturas indígenas na vida cotidiana da população latino americana em uma perspectiva descolonial. (SANTOS e MÜLLING, 2019).

The needs of indigenous professional education are permeated by institutional policies and its success depends on curricular adaptations, such as the use of orality in assessments (ESTEVÃO and BARBOSA, 2021). The pressure for the capitalist exploitation of indigenous territories today is incessant, whether for mining, to obtain natural resources such as wood and fishing, or for the leasing of indigenous lands for agribusiness. In all regions of the country, indigenous people have been harassed, due to the lack of alternatives, by agents of the predatory economic development model. It is necessary to support indigenous peoples so that they find sustainable alternatives for the autonomous management of their territories (SILVA, 2018).

The indigenous population in Brazil is significant and access to education for these peoples needs to be discussed. Guarantee not only their access, but also the permanence and success of students. The last census carried out records that the portion of the population that declared themselves to be of an indigenous color or race was 896,817 thousand people, representing 0.4% of the Brazilian population in the year of the referred survey. This demonstrates the great importance of studying and discussing indigenous education (IBGE, 2012).

In research carried out in the Capes database, indigenous technical secondary education is a scarce and recent topic, since its perspective can be associated with the expansion of the Federal Network of Education, Science and Technology, started in 2008, thus being an area of wide political and academic demands. The dissemination and deepening of studies in the area is important for the construction and consolidation of the rights to education of indigenous peoples (MULLING and SANTOS, 2016).

SEARCH FOR QUALIFICATION FOR THESE PEOPLE

In Brazil, we find a great diversity of schooling processes experienced by indigenous peoples. People who already have a long experience with formal education offered by governmental and non-governmental agencies, others started it more recently and still others resist accepting the school offered to them in their communities, fearing the impact of this action on the traditional organization of processes of learning and education of indigenous subjects (BRASIL, 2007).

An educational qualification that seeks not only their inclusion in the world of non-indigenous people, but that prepares them for their relationship with the distant external world of the indigenous community, a training capable of preparing them inside and outside their local context ( DOWBOR, 2007).

A ideia da educação para o desenvolvimento local está diretamente vinculada a esta compreensão, e à necessidade de se formar pessoas que amanhã possam participar de forma ativa das iniciativas capazes de transformar o seu entorno, de gerar dinâmicas construtivas. Hoje, quando se tenta promover iniciativas deste tipo, constata-se que não só os jovens, mas inclusive os adultos desconhecem desde a origem do nome da sua própria rua até os potenciais do subsolo da região onde se criaram. Para termos cidadania ativa, temos de ter uma cidadania informada, e isto começa cedo. A educação não deve servir apenas como trampolim para uma pessoa escapar da sua região: deve dar-lhe os conhecimentos necessários para ajudar a transformá-la (DOWBOR, 2007).

In this sense, it is important to discuss the methodologies used with indigenous peoples, public and institutional assistance policies for the inclusion, permanence and success of indigenous students. An intercultural school education, considering the reality and knowledge historically constructed by the indigenous community, makes the teaching and learning process more meaningful, bringing the formal disciplines offered closer to everyday life. Interculturality should contribute to overcoming divergences regarding coexistence with the different, facilitating the relationship with social and cultural plurality, being fundamental for the formation of all indigenous and non-indigenous students. It is important to break with the imposed teaching pattern and build strategies that approach school education that values traditional knowledge (SILVA and FELZKE, 2021).

CONCLUSIONS

Education seems to be the path for the integration of indigenous people and their formation for their own benefit and that of the community. This would probably mean that indigenous people would have opportunities similar to those of non-indigenous people.

The policy of quotas or affirmative actions is an attempt to reduce the social distance when it comes to access to places in education, including technical ones. Treating differently those who are different may help, in the future, the existence of a more egalitarian society.

The existence of centers of Afro-Brazilian and indigenous studies seems, albeit timidly, to contribute to research and dissemination on ethnic-racial identities and relations, aiming at reducing socio-educational distance and differences within institutions.

Despite the preparation, even if under construction, of institutions to serve a diverse public such as indigenous people, their access is still considered small, in a state such as, for example, Amapá. In order to attract indigenous students, it would be necessary to disseminate it more widely and closer to the reality of indigenous communities, including respecting their different culture, where the community functions as if it were an individual.

REFERENCES

BANIWA, G. A Lei das Cotas e os povos indígenas: mais um desafio para a diversidade. Cadernos do Pensamento Crítico Latino-Americano, n. 34, p. 18-21, 2013.

BRASIL. CONSTITUIÇÃO DA REPÚBLICA FEDERATIVA DO BRASIL DE 1988. Brasília DF, 1988. Disponível em: < https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm >. Acesso em: 21 mai 2021.

______. LEI Nº 9.394, DE 20 DE DEZEMBRO DE 1996. Brasília DF, 1996. Disponível em: < http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/L9394compilado.htm >. Acesso em: 21 mai 2021.

______. Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais da Educação Escolar Indígena. Brasília DF, 1999. Disponível em: < http://portal.mec.gov.br/cne/arquivos/pdf/1999/pceb014_99.pdf >. Acesso em: 21 mai 2021.

______. LEI N° 010172 , DE 9 DE JANEIRO DE 2001. Brasília DF, 2001. Disponível em: < http://portal.mec.gov.br/arquivos/pdf/L10172.pdf >. Acesso em: 14 mai 2021.

______. PROEJA – Programa Nacional de Integração da Educação Profissional com A Educação Básica na Modalidade de Educação de Jovens e Adultos. Brasília SP, 2007. Disponível em: < http://portal.mec.gov.br/setec/arquivos/pdf2/proeja_medio.pdf >. Acesso em: 05 mai 2021.

______. LEI Nº 11.892, DE 29 DE DEZEMBRO DE 2008. Brasília DF: Casa Civil 2008.

______. LEI Nº 12.711, DE 29 DE AGOSTO DE 2012. Brasília DF: Casa Civil 2012.

______. DECRETO Nº 7.566, DE 23 DE SETEMBRO DE 1909. Brasília – DF, 2020. Disponível em: < https://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/decret/1900-1909/decreto-7566-23-setembro-1909-525411-publicacaooriginal-1-pe.html >. Acesso em: 05 mai 2020.

DOWBOR, L. Educação e apropriação da realidade local. Estudos Avançados, v. 21, n. 60, p. 75-90, 2007.

ESTEVÃO, F. L. B. S.; BARBOSA, X. C. Wari’:Identidade E Diferença Na Composição Da Educação Profissional E Tecnológica No Instituto Federal De Rondônia. Educação Profissional e Tecnológica em Revista, v. 5, p. 99-123, 2021.

IBGE. Censo 2010: população indígena é de 896,9 mil, tem 305 etnias e fala 274 idiomas. Rio de Janeiro RJ, 2012. Disponível em: < https://censo2010.ibge.gov.br/noticias-censo?busca=1&id=3&idnoticia=2194&view=noticia >. Acesso em: 05 mai 2020.

IFAP. Plano De Desenvolvimento Institucional. Macapá AP, 2012. Disponível em: < http://www.siteantigo.ifap.edu.br/index.php?option=com_docman&task=cat_view&gid=121&Itemid=66 >.

______. Plano de Desenvolvimento Institucional. Macapá AP, 2019a. Disponível em: < https://ifap.edu.br/index.php/quem-somos/pdi >. Acesso em: 13 jan 2022.

______. RESOLUÇÃO Nº 123/2019/CONSUP/IFAP, DE 12 DE DEZEMBRO DE 2019. Macapá AP: CONSUP/IFAP: 1-5 p. 2019b.

______. EDITAL IFAP PROEN Nº 10/2021. Macapá AP, 2021. Disponível em: < https://ifap.edu.br/index.php/publicacoes/item/3872-edital-10-2021-proen-integrado-2022-1 >. Acesso em: 17 jan 2022.

IFFAR. Rede Federal completa 112 anos! , Santa Maria RS, 2021. Disponível em: < https://iffarroupilha.edu.br/noticias-jaguari/item/23223-rede-federal-completa-112-anos >. Acesso em: 05 jan 2022.

KOSTRYCKI, X. M. Para Além Do Acesso: A Política De Cotas E O Abandono Escolar No Instituto Federal Do Paraná, Campus Paranaguá. 2020. 104p. (Mestrado). Instituto Federal do Paraná, Curitiba PR.

MENDES, M.; OLIVEIRA, N.; VALENTE, H. Atuação docente na diversidade. Pará de Minas, MG: VirtualBooks, 2017. 85p.

MIRANDA, L. D. V. A. METODOLOGIA ATIVA: analisar o papel do projeto integrador no processo ensino/aprendizagem dos alunos dos cursos técnicos na modalidade subsequente do Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciências e Tecnologia no município de Oiapoque-AP. 2021. 29p. (Graduação). IFAP, Oiapoque AP.

MOEHLECKE, S. Ação Afirmativa: História E Debates No Brasil. Cadernos de Pesquisa, n. 117, p. 197-217, 2002.

MULLING, J. D. C.; SANTOS, S. V. D. Educação Escolar Indígena: levantamento das pesquisas sobre Ensino Médio e Ensino Técnico. Curitiba – PR: UFPR: 1-16 p. 2016.

QUARESMA, F. J. P.; FERREIRA, M. N. Os povos indígenas e a educação. Revista Práticas de Linguagens, v. 3, n. 2, p. 234-246, 2013.

RAMOFLY, B.; MACEDO, P. C. S. História e Memóriada Educação Profissional e Tecnológica: as narrativas do processo de implantação e expansão do Instituto Federal do Amapá. Revista Labor, v. 2, n. 24, p. 372-395, 2020.

RIBEIRO, D. Os índios e a civilização. Rio de Janeiro RJ: Círculo do Livro, 1989. 460p.

SANTOS, S. V.; MÜLLING, J. C. A presença de estudantes indígenas na educação profissional e tecnológica. Educação, v. 42, n. 3, p. 475-485, 2019.

SILVA, E. C. A. Povos indígenas e o direito à terra na realidade brasileira. Serv. Soc. Soc., n. 133, p. 480-500, 2018. Disponível em: < https://www.scielo.br/j/sssoc/a/rX5FhPH8hjdLS5P3536xgxf/?lang=pt >.

SILVA, M. A. X.; FELZKE, L. F. Aspectos Culturais E Metodológicos No Processo De Aprendizagem Dos Estudantes Indígenas Macuxi: Experiências Do Instituto Federal De Roraima Campus Amajari. v. 5, p. 77-98, 2021.

SOUZA, F. C. S.; SILVA, S. H. S. C. Institutos Federais: Expansão, Perspectivas E Desafios. Revista Ensino Interdisciplinar, v. 2, n. 5, p. 17-26, 2016.

SOUZA, K. C. B. D. et al. Evasão escolar no Ensino Médio Integrado da Rede Federal de Educação nas capitais da Região Norte, Brasil (2014-2018). Research, Society and Development, v. 9, n. 8, p. 1-13, 2020.

TORRES, L. O.; DIAS, J. C.; FILHO, J. C. M. B. Ações afirmativas como instrumento de promoção da igualdade de recursos: o caso do programa de trainee exclusivo para negros do Magazine Luiza. Revista de Direito, v. 13, n. 3, p. 01–24, 2021.

WANDROSKI, S. F.; COLEN, F. R. C. As ações afirmativas para ingresso de estudantes no Instituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia de Rondônia. O Social em Questão, n. 32, p. 165-182, 2014.

APPENDIX – FOOTNOTE

6. Educação Profissional e Tecnológica (EPT).

7. Lei de diretrizes e bases da educação nacional (LDB).

8. Plano Nacional de Educação (PNE).

9. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE).

10. Centros Federais de Educação Tecnológica (CEFETs).

11. Unidades de Ensino Descentralizadas (UNEDs).

12. Plano de Desenvolvimento Institucional (PDI).

13. Núcleo de Estudos Afro-Brasileiros e Indígenas – Neabi/Ifap.

[1] Lyricist, Specialist in Special and Inclusive Education, Student of the Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação Profissional e Tecnológica (PROFEPT IFAP).

[2] Agronomist, Specialist in Teaching in Professional and Technological Education, Doctor in Entomology, Professor and researcher at the Instituto de Ensino Básico, Técnico e Tecnológico do Amapá (IFAP) and the Programa de Pós Graduação em Educação Profissional e Tecnológica (PROFEPT IFAP).

[3] Biomedical, PhD in Tropical Diseases, Professor and researcher at the Campus Macapá Medicine Course, Universidade Federal do Amapá (UNIFAP).

[4] PhD in Psychology and Clinical Psychoanalysis. Ongoing PhD in Communication and Semiotics at the Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo (PUC/SP) . Master’s Degree in Religious Sciences from Universidade Presbiteriana Mackenzie. Master in Clinical Psychoanalysis. Degree in Biological Sciences. Degree in Theology. He has been working with Scientific Methodology (Research Method) for more than 15 years in the Guidance of Scientific Production of Master’s and Doctoral Students. Specialist in Market Research and Health Research. ORCID: 0000-0003-2952-4337.

[5] Biologist, Ph.D. in Theory and Research of Behavior, Professor and researcher at the Bachelor’s Degree in Chemistry at the Instituto de Ensino Básico, Técnico e Tecnológico do Amapá (IFAP) and at the Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação Profissional e Tecnológica (PROFEPT IFAP).

Sent: January, 2022.

Approved: January, 2022.