ORIGINAL ARTICLE

VIANA, Maria Betânia Rossi [1], SILVA, Jose Amauri Siqueira da [2]

VIANA, Maria Betânia Rossi. SILVA, Jose Amauri Siqueira da. The teaching-learning challenge of the history curriculum component: in reading, interpretation and textual production. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year. 07, Ed. 10, Vol. 02, pp. 05-23. October 2022. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/education/curriculum-component, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/education/curriculum-component

ABSTRACT

This article analyzes the causes that lead some students in the sixth year of Elementary School, from the Padre Faliero Educational Center and State School Professora Maria Curtarelli Lira, to have so many difficulties in the classes of the Curriculum Component of History at the time of Reading, Interpretation and Text Production. The study was guided by the following question: Why do some students in the sixth year of Elementary School, from Padre Faliero Educational Center and State School Professora Maria Curtarelli Lira, have so many difficulties in the History Curriculum Component classes at the time of Reading, Interpretation and Production Textual? With the general objective: To analyze the main causes that lead some students in the sixth year of Elementary School, from the Padre Faliero Educational Center and State School Professora Maria Curtarelli Lira, to have so many difficulties in the classes of the Curricular Component of History at the time of Reading , Interpretation and Text Production. The subject of the study was two hundred and twenty-eight students in the sixth year of the Padre Faliero Educational Center and State School Professora Maria Curtarelli Lira, in the municipality of Apuí, Amazonas, Brazil, and four professors who teach the Curriculum Component of History in both schools institutions. The approach was qualitative, analytical, descriptive, with the application of questionnaires to the students and interviews with the professors, with analysis of the minutes of notes, Pedagogical Political Projects and Teachers’ Planning. The information obtained was arranged in a descriptive and explanatory manner. Coming to the following conclusion: a large percentage of sixth year students do not have fluency in reading, interpretation and textual production, the lack of diversification of methodologies or innovative methodologies bore the students leaving them dispersed and unmotivated.

Keywords: Students, Teachers, Innovative Methodologies.

1. INTRODUCTION

The article deals with the theme: “The Teaching-Learning Challenge of the Curricular Component of History: in Reading, Interpretation and Textual Production”, aimed at the sixth year of Elementary School at the Padre Faliero Educational Center and State School Professora Maria Curtarelli Lira, developed in the municipality of Apuí/AM[3].

The difficulty encountered by some students in the sixth year of Elementary Education at the aforementioned schools, in teaching and learning the Curriculum Component of History at the time of classes in the approach of Reading, Interpretation and Textual Production is something disturbing, it has been observed for many years, the way in which the themes of this Curricular Component are worked on, successes, failures and challenges, faced by educators trained in this area of knowledge, to approach it pedagogically.

The failure rate or insufficient grades in the History Curriculum Component is something alarming. Teachers need to expand their methodologies, making their classes more attractive and enjoyable, building and rebuilding History with their students, awakening in them the pleasure of learning and understanding its importance.

Although our country establishes in its Federal Constitution of 1988, in its Article 25:

A educação, direito de todos e dever do Estado e da família, será promovida e incentivada com a colaboração da sociedade, visando ao pleno desenvolvimento da pessoa, seu preparo para o exercício da cidadania e sua qualificação para o trabalho (BRASIL, 1998, p. 151).

The students enter the sixth year of Elementary School with disabilities in Reading, Interpretation and Textual Production. Teachers of the Curricular Component of History are not achieving the desired result in their classes, considering that they use Reading, Interpretation and Textual Production of theories and few practical classes, causing a percentage of students to be retained or with insufficient grades, forming in these individuals a negative view of the Curricular Component of History, as boring and meaningless for their lives, both at school and personally.

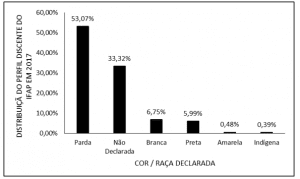

The target audience of the research, which guided the production of this article, four teachers and two hundred-twenty-eight students who attend the sixth year of Elementary School at the Padre Faliero Educational Center and at the State School Professora Maria Curtarelli Lira, who live in the Urban Area and Rural in the municipality of Apuí, located in the south of Amazonas.

Having as a guiding question: Why do some students of the sixth year of Elementary School, from the Padre Faliero Educational Center and from the State School Professora Maria Curtarelli Lira, have so many difficulties in the History Curriculum Component classes at the time of Reading, Interpretation and Textual Production?

General objective: To analyze the main causes that lead some students in the sixth year of Elementary School, from the Padre Faliero Educational Center and from the State School Professora Maria Curtarelli Lira, to have so many difficulties in the History Curriculum Component classes at the time of Reading, Interpretation and Text Production.

And as specific objectives: Specify what are the possible difficulties encountered by some students at the time of Reading and Interpretation and Textual Production in the Curricular Component of History; Explain the difficulties faced by teachers of the Curricular Component of History when teaching and learning in their classes; identify the teaching methodologies that are used by teachers of the Curricular Component of History in teaching-learning activities.

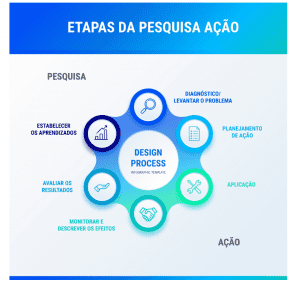

A mixed research was used, that is, qualiquantitative, for the collection of data, analyzing them carefully, based and validated with the authors who approach this theme.

2. THE DIFFICULTIES THAT STUDENTS ENCOUNTER IN READING, INTERPRETATION AND TEXTUAL PRODUCTION AND HOW THIS COMMITS THE TEACHING LEARNING OF THE HISTORY CURRICULUM COMPONENT

The Portuguese Language Curricular component at school is the basis of all teaching, since everyone needs to know how to read, interpret and produce texts to learn about the Curricular Components of History. And those who cannot learn it are stagnant, because all individuals need it to read a multitude of things, such as: letters, notices, etc. Even for moving from one place to another, accessing the internet, using WhatsApp, to get a fairer job, to go to the market to do your shopping, and for classes in the Curricular Component of History, this skill is of paramount importance.

Children from birth are knowledge builders, they don’t wait to be in school to start learning. But parents can influence the children’s learning, because from the simple fact of reading the newspaper to find out about a certain fact, or even receiving messages from family members or friends, demonstrating to children that reading and the written word are of extreme importance.

As linguagens, antes articuladas, passam a ter status próprios de objetos de conhecimento escolar. O importante, assim, é que os estudantes se apropriem das especificidades de cada linguagem, sem perder a visão do todo no qual elas estão inseridas. Mais do que isso, é relevante que compreendam que as linguagens são dinâmicas, e que todos participam desse processo de constante transformação (BRASIL, 2017, p. 61).

Children need to start their first contacts with reading and writing in a special way, where readings and mechanized copies are not imposed, but rather, carry them out with total freedom, being able to create sounds, invent words, since, children from large urban centers live in contact with words in their daily routine, in advertisements, signs, commercials, etc.

“The history of writing in children begins long before the teacher puts the pencil in their hand and shows them how to form the first letters (VIGOTSKI; LURIA and LEONTIEV, 2018, p. 143).”

Parents most of the time, in their busy day-to-day, full of tasks, do not make time to read to their children, or provide them with contact with words. Preschools are responsible for creating this literate environment for children, with books, advertisements, posters and other means, initiating the socialization of reading and the written word. For Emilia Ferreiro:

A tão comentada ‘prontidão para a lecto-escrita’ depende muito mais das ocasiões sociais de estar em contato com a língua escrita do que de qualquer outro fator que seja invocado. Não faz sentido deixar a criança à margem da língua escrita, “esperando que amadureça”. Por outro lado, os tradicionais “exercícios de preparação” não ultrapassam o nível do exercício motriz e perceptivo, quando é o nível cognitivo aquele que está envolvido (e de forma crucial), assim como complexos processos de reconstrução da linguagem oral, convertida em objeto de reflexão (FERREIRO, 2010, p. 101).

One of the factors that most influence the difficulties they have when reading comes from the students’ homes, as it is observed that most parents do not have the habit of reading, thus not awakening the yearning for reading in their children. The school tries to encourage them, but if there is no collaboration from the parents, it gets a little complicated.

Considering, that the student normally stays in the classroom only four hours a day and the other twenty spend at home with their families or with nannies. “Vygotsky, in a Synthesis, writes about imitation, which is part of teaching children to learn through play (2014)”, he agrees with him, since the adult is a mirror for the child.

The reality of most students does not allow them to have experiences outside the school environment with reading, interpretation and textual production or with any other means that can provide them with experience with it. Thus improving their performance when developing the reading, interpretation and production of texts.

Both schools, which were the object of the research, serve a clientele in the rural area, which on average take more than four hours, inside a school bus on the way from their home to school. By greatly limiting your extra-class study time and reading development.

However, one should not forget that reading, interpretation and textual production are essential, as everyone needs reading in their daily lives, not just for teaching purposes in schools. The difficulty in reading, textual production and interpretation can cause many problems for students, who will be our future professionals. It can be observed that most Brazilians find immense difficulty in these questions. “The child who grows up in a “literate” environment is exposed to the influence of a series of actions. And when we say actions, in this context, we mean interactions. Through adult-adult, adult-child interactions (FERREIRO, 2018, p. 53).”

The gap that remains in learning during the early years of Elementary School is causing frustrations in both teachers and students in the Curricular Component of History, and compromising their success in teaching and learning.

3. METHODOLOGIES THAT CAN HELP THE SUCCESS OF TEACHING LEARNING IN THE CLASSES OF THE HISTORY CURRICULUM COMPONENT

The Curricular Component of History raises many questions among the students, one of the most frequently heard by teachers is: Why study something that happened even before one’s birth? Or History speaks only of the past. And many others, in the same style.

It must be very clear: What is History? What is it for? Reflect deeply on its meaning for educators and students. Because there is a need to be able to address any topic, such as passing security or awakening and sharpening curiosity, when producing knowledge together with the student, having a clear concept on the said topic.

Each area has its own methodology. The teaching methodology is the use of diversified methods in the process of teaching and learning development. In Brazil, the main Teaching Methods used are: Traditional or Content Method, an approach that is predominant in public schools and some private schools in Brazil, for this reason it is the best known.

In this method, the focus is on the Professor, holder of knowledge, whose function is to pass it on to the student. This method is well suited to the form of assessments used in Brazilian entrance exams and in the National Secondary School Examination (ENEM)[4]. Some of the most prestigious schools in the world, such as the English and American ones, use the traditional teaching method.

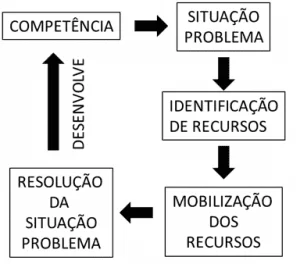

Jean Piaget’s Constructivist Method: also influenced by the Argentinean psychologist Emília Ferreiro. For constructivists, knowledge is constructed actively by the subject and not received passively by the teacher as in the traditional method. Each student is seen as a unique individual, with a particular learning time and teamwork is valued, stimulating thinking and solving proposed problems.

Lev Vygotsky’s Socio Interactionism Method: it is a variation of constructivism, in this method a fundamental role is attributed to social relations in learning.

Maria Montessori’s Montessori Method: method in which the student must seek self-affirmation and construction of knowledge. It is up to the teachers to help them throughout the process, cooperating with the development of individuals so that they become creative, autonomous, reliable and initiative individuals. This method was created with children in mind, and therefore it is more common to find it in kindergarten schools.

The Freiriano method: created by Paulo Freire, was innovative for using the students’ experiences as a basis for education through the use of generative words, which were chosen according to the students’ reality.

Ao referir-se ao “método tradicional”, professores e alunos geralmente o associam ao uso de determinado material pedagógico ou a aulas expositivas. Existe uma ligação entre o método tradicional e o uso de lousa, giz e livro didático: o aluno, em decorrência da utilização desse material, recebe de maneira passiva uma carga de informações que, por sua vez, passam a ser repetidas mecanicamente de forma oral ou por escrito com base naquilo que foi copiado no caderno ou respondido nos exercícios propostos pelos livros (BITTENCOURT, 2018, p. 48).

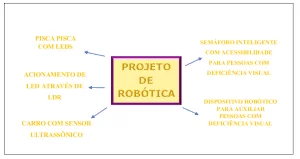

To make the class of the History curricular component gain a new meaning in the student’s school life, some methodologies can be used, let’s mention a few, selected among several existing ones.

Oral Sources/Memory: Oral history is a methodology in which interviews are used, testimonies are collected from people who witnessed some events and can report them. It brings to the study of history a more concrete and close view of the reality of those who study it, contributing to the understanding of the past by future generations, of facts and experiences lived by other people.

A história oral tem como alicerce principal entrevistas ou depoimentos de pessoas que vivenciaram determinados fatos ou que têm informações ou memórias ligadas ao tema pesquisado. Para as crianças, essa pode ser uma forma interessante de ter acesso a informações históricas sobre fatos mais recentes, ou sobre a história do seu bairro ou cidade, com relação a costumes etc. Ou seja, tudo que pode ser alvo da memória de certas pessoas pode ser explorado pela história oral (ZUCCHI, 2012, p. 151).

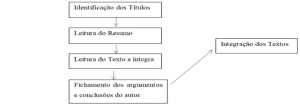

Analysis of Texts by Different Authors and Historical Documents: the choice of texts should preferably be from different historiographic currents and analyze the historical fact from different perspectives, always taking into account the difficulty that some students still have in reading, and add new words to the enrichment of students’ vocabulary, guiding them to seek solutions to their doubts, arousing their curiosity and instigating them to dialogue.

Na atualidade, o trabalho com fontes ou documentos históricos é considerado um dos procedimentos fundamentais em sala de aula, pois amplia o conhecimento sobre o trabalho do historiador, estimula a observação e permite uma maior reflexão sobre conteúdos através dos documentos (BRODBECK, 2012, p. 34).

The use of Image/Photography in teaching History with the aim of performing a critical analysis of the images contained in textbooks, as well as measuring the knowledge achieved by students through the representation of these historical events and the figures produced by them.

Therefore, the choice of image to be worked on should not be carried out in a naive way, when analyzing it it is necessary to ask questions. When? As? By whom was it produced? For what and for whom was this production made? The images must be selected with criticality and common sense to then be taken to the appreciation of the students.

Hoje, a presença abundante das mídias digitais em nosso cotidiano já é referida por alguns como “fotolocura ou “explosão de imagens”, indicando um movimento de mudanças qualiquantitativa, e não necessariamente qualitativas, na nossa sociedade. Mas é certo que, na extensa cultura fotográfica estabelecida há quase dois séculos, as transformações estão em ritmo acelerado e as especulações sobre o futuro da fotografia são muitas. As aulas de história oferecem grande oportunidade para a reflexão sobre essas transformações (PINTO e TURAZZI, 2012, p. 99).

The seminars also provide an opportunity to get to know our students better and lead us to guide them towards building their citizenship. The objective of this methodology is to develop the student, as he presents himself at different times, with different themes, little by little he overcomes shyness and starts to speak with ease to his colleagues.

Films are also excellent methodological tools for teaching History, taking into account the wide range of film productions, portals such as Youtube, available for free on the Internet. Expanding the thematic and documental field, allowing the student to know different approaches, concepts and lead them to reflect on their own historical and social space.

A popularização das tecnologias da Informação da Comunicação e a Ampla oferta e produção cinematográfica em DVDs vêm facilitando o acesso às produções audiovisuais que oferecem muitas alternativas para o trabalho pedagógica (SILVA e PORTO, 2012, p. 51).

Cultural Heritage – can be divided into two groups: The one produced by men such as architectural, archaeological, historical, biographical, scientific and aesthetic assets. And those that were not created by him, such as forest parks and ecological reserves.

Art. 216. Constituem patrimônio cultural brasileiro os bens de natureza material e imaterial, tomados individualmente ou em conjunto, portadores de referência à identidade, à ação, à memória dos diferentes grupos formadores da sociedade brasileira, nos quais se incluem:

I – As formas de expressão;

II – Os modos de criar, fazer e viver;

III – As criações científicas, artísticas e tecnológicas;

IV – As obras, objetos, documentos, edificações e demais espaços destinados às manifestações artístico-culturais;

V – Os conjuntos urbanos e sítios de valor histórico, paisagístico, artístico,arqueológico, paleontológico, ecológico e científico (BRASIL, 1988, p. 154).

Museums are an excellent field to explore history, a well-defined itinerary in line with the content to be taught, helps to promote a more enjoyable learning experience, you can also take a tour without leaving the classroom, making an online visit to virtual museums.

Round Table, aims to promote a debate on a given topic by raising questions. It is expected to allow students to assume the role of historian, as well as to perceive different versions of the same historical fact.

The Internet is an excellent ally to pedagogical practices in the Curriculum Component of History. Well, the students are from the technology generation and know how to operate any computer, notebook, tablet and the most used, and common to them, the cell phone very well. Nothing is more pleasant than uniting what they love so much with learning.

Music in the classroom, its use is very important. Relating it to the topics studied, a good measure for the sixth year, when studying the ancient peoples of the African continent, getting them to correlate our culture with theirs, since many habits were inherited from them. Transforming, in this way, a class that would be monotonous for the students into a pleasant one, leading them to make a historical analysis of different moments in history.

The inverted classroom, this methodology is very interesting to develop in the History Curriculum Component classes. Considered a great innovation in the learning process, it is a teaching methodology through which the logic of organizing a classroom is completely inverted.

Instead of the teacher passing on the whole theory at the time of class, this theory is studied beforehand by the students, either online through a platform created by the teacher with videos, texts or images, or by indicating films, books, magazines and other materials that talk about the object of knowledge under study. Remembering that the teacher needs to plan and organize the subjects that will be studied, as well as the videos that are relevant and appropriate to the age group of the students.

The individual must acquire the necessary skills to build knowledge about the historical context, and using varied methodologies, one can seek to develop in him an appreciation for the Curriculum Component of History as well as a better performance in teaching and learning it, developing historical knowledge in a pleasant way.

4. DATA ANALYSIS FROM THE PADRE FALIERO EDUCATIONAL CENTER AND STATE SCHOOL PROFESSORA MARIA CURTARELLI LIRA

4.1 OBSERVATION OF SCHOOLS

Both schools have a Pedagogical Political Project that guides school planning, despite the method indicated in the PPPs not being put into practice, as the use of the traditional method was observed, which is not mentioned and neither of the two PPPs.

Both have a well-functioning structure, a satisfactory staff, have a computer lab, although at the moment they are not used by teachers and students, the internet is limited for the school’s internal services, and cannot be used for classes in classroom and not even for students to carry out research, despite having Data Show, television and computers, their use is limited because something is always missing, from batteries to control televisions to audio and HDMI cables, and support for the organization of this material.

4.2 ANALYSIS OF SURVEY QUESTIONNAIRE WITH SIXTH GRADE STUDENTS

The students, when asked about their mastery in reading, interpretation and text production, two hundred and three students who were present in the classroom when the questionnaires were applied, gave the following answers: 65¨% answered yes, that they know read, interpret and produce texts fluently; 24% responded that they did not master this skill and twenty-five students, totaling 11%, were absent on the day the questionnaire was applied.

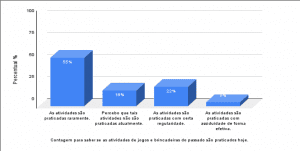

It can be observed that when asked if they find it difficult to carry out the activities developed in the curricular component of History, they gave us the following answer: 52% stated that they rarely find it; 11% often find it; 4% always encounter difficulties; 15% never find it difficult to carry out the activities and 11% were absent from the room and did not give an opinion.

When asked about the use of the textbook as the only didactic tool for teaching and learning in the History Curricular Component classes, the following results were obtained: 62% of the students answered yes, the teacher only uses the textbook; 26.5% no; 0.45% abstained from answering and 11% were absent when the questionnaire was applied.

On the frequency of media use by teachers at the time of teaching-learning, in the classroom: 11% stated that the teacher always uses it; 21% sometimes the teacher uses it; 57% stated that they never use media in the classroom and 11% did not give an opinion because they were absent.

When asked if the teacher contextualizes the Teaching objects of the History Curricular Component classes with the students’ reality, we were given the following answers: 51% yes; 9% no; 29% sometimes and 11% were absent and did not give an opinion.

Of the students, 84% considered the History Curricular Component class important in their school life; 4.1% answered that it is not important; 0.45% more or less; 0.45 abstained from answering and 11% were absent when the questionnaire was applied.

Regarding the frequency that their parents or guardians attend school meetings, 67.5% answered that a frequency of 100%;14.5% of 60% to 80% of attendance; 7% with less than 50% attendance and 11% were absent when the questionnaire was applied.

When asked about how often their parents or guardians participate in projects developed at school. The following results were obtained: 34.5% answered that a frequency of 100%; 31.5% from 60% to 80% attendance; 22.1% with less than 50% attendance; 0.9% abstained from answering and 11% were absent when the questionnaire was applied and did not respond.

In the opinion of 82% of students, the bad behavior of colleagues in the classroom, and the mess they make hinder their learning; 7% that it does not disturb and 11% were absent and did not give an opinion.

When asked about the importance of the participation of their parents or guardians in their school life. They gave the following answers: 85.5% said yes, it is important for their parents or guardians to participate in their school life; 3.5 that it is not important and 11% were absent and did not give an opinion.

4.3 ANALYSIS OF THE INTERVIEW WITH TEACHERS WHO TEACH THE HISTORY CURRICULUM COMPONENT FOR THE SIXTH GRADE

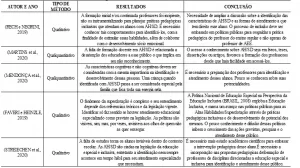

All teachers who teach the Curricular Component of History at the Padre Faliero Educational Center and at the State School Professora Maria Curtarelli Lira are female.

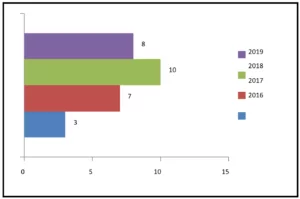

When asked about their teaching experience, the following information was obtained: 25% have 05 to 10 years of teaching experience; 25% have 10 to 20 years of teaching; 25% have 20 to 25 years of teaching and 25% have 25 to 30 years of teaching.

As for training, all teachers have a higher level, 75% in the Curricular Component of History and 25% a degree in another area, which in this case would be teacher A2 who has training in the curricular component of language, that is, a Degree in Letters and Literature.

When asked if they have specialization, it was obtained: 100% have specialization; 0% master’s and 0% doctorate. Teachers A1, B1 and B2 have specialization with Emphasis in the area of Social Sciences and teacher A2 with emphasis in the area of Language.

When asked if the students correctly read and interpreted the activities of the Curriculum Component of History, the unanimous answer was 100% sometimes; 0% always and 0% never.

All the teachers interviewed stated that they use different methodologies in the classroom when teaching and learning.

When asked what these methodologies would be, the following answers were obtained:

Teacher A1- Uses text readings, maps, pictures; videos, posters and drawings;

Lecturer A2- Reading rewriting, films, work in groups, dramatization;

Teacher B1- Video lessons and maps;

Lecturer B2- Lectures; Reading and Solving exercises; Analysis of images and maps;

Group dynamics; Exhibition of posters; Video display; Individual and group research; Printed material and rewriting of texts.

All reported that they use other teaching materials to prepare their classes, in addition to the textbook provided by the educational institution for both teachers and students.

When asked what these teaching materials would be, the following answers were obtained:

Teacher A1- Other support books; dictionaries; terrestrial globe, history magazines and others;

Teacher A2- Technological resources;

Lecturer B1- Research On the Internet and in other books;

Teacher B2- In addition to the textbook, the Internet is used as a source of research to plan classes in the Curriculum Component of History.

Regarding the technological resources they use in the classroom for a better understanding of the Curricular Component of History, the following responses were obtained: 100% use of videos, television, datashow and pendrive; only 50% use a computer/laptop and pendrive, for a better understanding of the History Curriculum Component classes.

When asked if the educational institution where they work offers some support for the use of media in their classes to make them more attractive for students: 75% said yes, the school provides the necessary support and 25% said no, the institution does not provide the necessary support.

On the issue of bad behavior or the lack of limits of the students, it was asked if this attitude harms the progress of the pedagogical work in the classroom, the following data were obtained: 75% said yes, it harms the progress of the pedagogical work and 25% sometimes harms.

When asked about the attendance of the students’ parents or guardians at school meetings, the following answers were obtained: 0% for 100% attendance; 75% that the attendance of parents or guardians at meetings ranges from 80% to 60% and 25% stated that parents or guardians have a frequency of less than 50% attendance.

When asked about the number of parents or guardians of the students who participate in the Projects developed in the Schools, the following answers were obtained: 0% for 100% participation; 0% for participation from 80% to 60% and 100% stated that parents or guardians have a frequency of less than 50% participation in projects developed at school.

When asked about the absence of parents or guardians in the students’ school life, it increases the difficulty they encounter at the time of teaching-learning, all were unanimous in their answer, 100% yes; 00% for no and 00% for sometimes.

4.4 PLANNING ANALYSIS OF TEACHERS IN THE HISTORY CURRICULUM COMPONENT AT PADRE FALIERO EDUCATIONAL CENTER AND STATE SCHOOL PROFESSORA MARIA CURTARELLI LIRA

Teacher A1 does her planning in the notebook, listing the contents, without describing the methodology used for teaching and learning with the students.

Teacher A2 does her bimonthly planning, listing objectives and content, without describing the methodology used for teaching and learning with students.

Teacher B1 plans her classes for two months, detailing the classes and citing the methodology used, without making a detailed description, and also mentions the form of evaluation used to verify the students’ learning.

Teacher B2 plans her classes for two months, with objectives, mentions the methodology used and the form of evaluation that will be applied to verify the students’ learning.

The analyzed plans do not detail the methodology used in the classroom, the use of the traditional method is observed, in the classes that are mostly expository and in the activities developed in the classrooms, in both schools. With rare use of videos, group work and lectures.

4.5 ANALYSIS OF STUDENTS’ GRADES IN THE CURRICULUM COMPONENT OF HISTORY AT PADRE FALIERO EDUCATIONAL CENTER AND STATE SCHOOL PROFESSORA MARIA CURTARELLI LIRA

When analyzing the grades of students in the sixth year of elementary school in both schools, whose average is a grade of six, five points and nine tenths or less, grades are considered red or insufficient for students to be promoted. The following quantitative results were obtained:

6th year students A: In the first two months: 24% of the averages are insufficient, between 0 and 5.9 points; 60% of averages are reasonable between 6.0 and 7.9 points; 16% of averages are considered good between 8.0 and 9.9; and no student managed to get a ten, that is, an excellent concept.

In the Second Bimester: 14% of the averages are insufficient between 0 and 5.9 points; 20% of averages are reasonable between 6.0 and 7.9 points; 62% of averages are good between 8.0 to 9.9; and 4% of the averages are ten, an excellent concept.

6th year B students: In the first two months: 24% of the averages are insufficient between 0 and 5.9 points; 71% of averages are reasonable between 6.0 and 7.9 points; 5% of averages are good between 8.0 to 9.9; and no student was able to obtain a grade of ten, that is, an excellent concept.

In the Second Bimester: 9% of the averages are insufficient between 0 and 5.9 points; 27% of averages are reasonable between 6.0 and 7.9 points; 64% average good between 8.0 and 9.9; and no one managed to get a ten, that is, an excellent concept.

6th year students C: In the first two months: 16% of the averages are insufficient between 0 and 5.9 points; 68% of the averages are reasonable between 6.0 and 7.9 points; 16% of averages are good between 8.0 to 9.9; and no student managed to get a ten, that is, an excellent concept.

In the Second Bimester: 16% of insufficient averages between 0 and 5.9 points; 42% of reasonable averages between 6.0 and 7.9 points; 42% of averages are good between 8.0 to 9.9; and no student was able to obtain a grade of ten, that is, an excellent concept.

Students of the 6th year D: In the first two months: 28% of insufficient averages between 0 and 5.9 points; 24% of reasonable averages are between 6.0 and 7.9 points; 48% of averages are good between 8.0 to 9.9; and no student was able to get a grade of ten, that is, an excellent concept.

In the Second Bimester: 24% of the averages are insufficient between 0 and 5.9 points; 20% of averages are reasonable between 6.0 and 7.9 points; 56% of averages are good between 8.0 to 9.9; and no student managed to get a ten, that is, an excellent concept.

6th year students E: In the first two months: 17% of averages are insufficient between 0 and 5.9 points; 22% of the averages are reasonable between 6.0 and 7.9 points; 61% of averages are good between 8.0 to 9.9; and no student obtained a grade of ten, that is, an excellent concept.

In the Second Bimester: 12% of the averages are insufficient between 0 and 5.9 points; 56% of the averages are reasonable between 6.0 and 7.9 points; 28% of averages are good between 8.0 to 9.9; and 4% of the averages are ten, an excellent concept.

6th year students 01: In the first two months: 11% of the averages are insufficient between 0 and 5.9 points; 44% of the averages are reasonable between 6.0 and 7.9 points; 42% of averages are good between 8.0 to 9.9; and 3% of the average ten, excellent concept.

In the Second Bimester: 11% are insufficient averages between 0 and 5.9 points; 30% of averages are reasonable between 6.0 and 7.9 points; 56% of averages are good between 8.0 to 9.9; and 3% of the average ten, excellent concept.

6th year students 02:

In the first Bimester: 6% of the averages are insufficient between 0 and 5.9 points; 26% are reasonable averages between 6.0 and 7.9 points; 65% of averages are good between 8.0 to 9.9; and 3% are average ten, excellent concept.

In the Second Bimester: 6% of the averages are insufficient between 0 and 5.9 points; 28% of the averages are reasonable between 6.0 and 7.9 points; 60% of averages are good between 8.0 to 9.9; and 6% of the averages are ten, an excellent concept.

6th year students 03: In the first two months: 7% of the averages are insufficient between 0 and 5.9 points; 39.5% average are reasonable between 6.0 to 7.9 points; 39.5% of averages are good between 8.0 to 9.9; and 14% of the averages are ten, an excellent concept.

In the Second Bimester: 11% of the averages are insufficient between 0 and 5.9 points; 33.5% of the averages are reasonable between 6.0 and 7.9 points; 37% of are good averages between 8.0 to 9.9; and 18.5% of the averages are ten, an excellent concept.

5. CONCLUSION

This article aimed to: Analyze the main causes that lead some students of the sixth year of Elementary School at Padre Faliero Educational Center and State School Professora Maria Curtarelli Lira to have so much difficulty in the History Curriculum Component classes at the moment of Reading, Interpretation and Text Production, which was achieved.

And as a guiding question: Why do some students in the sixth year of Elementary School, from the Padre Faliero Educational Center and from the State School Professora Maria Curtarelli Lira, have so many difficulties in the History Curriculum Component classes at the time of Reading, Interpretation and Textual Production?

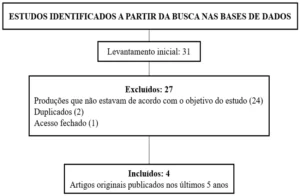

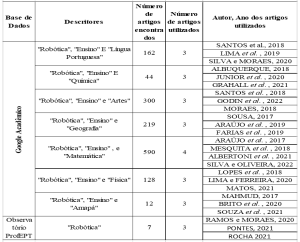

Through observation of schools, application of questionnaires to students, interviews with teachers, analysis of planning and notes for the first half of 2019. An explanation was sought for the questions above. With all the information analyzed and quantified, it was possible to reach the following conclusions, which answer the guiding question above.

That the difficulty that students find in the History Curriculum Component classes at the time of Reading, Interpretation and Textual Production is due to the fact that twenty-one percent of the students do not satisfactorily develop Reading, Interpretation and Textual Production.

That the lack of participation of parents in meetings and projects developed by schools, bad behavior and lack of limits by students, are constant difficulties faced by teachers in the development of their pedagogical work and reflect on the teaching and learning of students.

It was also found that the lack of diversification of methodologies used at the time of teaching and learning also contributes to the non-excellence of learning the Curriculum Component of History, making students see it as boring and meaningless for their school life.

The Pedagogical Political Projects of both researched institutions cite methodologies based on projects, on Vygotsky’s socio-interactionism and on Piaget’s constructivism. But, by observing the school routine, it is concluded that they are not fully put into practice.

The textbook and lectures are widely used in the classroom at the time of teaching and learning, rarely using TV or Datashow. Students do not have access to the internet and neither do teachers. The professional staff of the two schools is excellent, all graduates, postgraduates and some studying for a master’s or doctorate.

The grades that quantify and classify students in terms of their performance do not show the desired excellence, some students fail to reach the average required by the institutions.

Although lectures have their advantages, just using them can make teaching boring. The use of innovative and varied methodologies contribute to greater interaction and learning among students. Through the analysis of the plans it can be observed that they are scarce in both schools.

Therefore, it can be concluded that for Teachers to be more successful at the time of teaching and learning, they need to: Plan classes with clear and detailed methodologies; implement innovative and diversified methodologies for their History Curriculum Component classes; seek methodological supports when necessary for a good development of their classes; recover the participation of parents in their children’s school life and in the projects developed by the school.

And for the students to overcome the difficulty they have when teaching and learning the curricular component of History: Participate more diligently in the classes; interact with other colleagues; contributed to their learning and that of their colleagues; seeking to learn to read, write and interpret fluently.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

ALVARENGA, E. M. D. METODOLOGIA DA INVESTIGAÇÃO QUANTITATIVA E QUALITATIVA: Normas técnicas de apresentação de trabalhos científicos. Tradução de Amarilhas Cesar. 2 ed. ed. Assunção: A4 Diseños, 2014.

ASSOCIAÇÃO BRASLIEIRA DE NORMAS TECNICAS. 14724: Informação e Documentação – Trabalhos Acadêmicos – Apresentação, Rio de Janeiro, 2011.

BRASIL, B. N. C. C. Educação é a Base. Brasília, MEC/CONSED/UNDIME, 2017. Disponível em: <http:// basenacionalcomum.mec.gov.br/imagens_publicacao.pdf>. Acesso em: 21 Abril 2019.

______. Constituição(1988). Constituição Federal do Brasil, Brasília: Senado Federal, 1998.

______. Secretaria de Educação Fundamental. Parâmetros Curriculares Nacionais: História/Geografia, Brasília: MEC/SEF, 1998.

BRODBECK, M. D. S. L. Vivenciando a História – Metodologia de Ensino da História. Curitiba: Base Editorial, 2012.

FERREIRO, E. Com todas as letras. 17. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2017.

______. Com todas as letras. 26. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2010.

______. Reflexão sobre alfabetização. 25. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2018.

FRANCHI, E. Pedagogia do Alfabetizar Letrando: da oralidade à escrita. 9. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2012.

PINTO, J. P.; TURAZZI, M. I. Ensino de História: diálogos com a literatura e a fotografia. São Paulo : Moderna, 2012.

PORTAL do Governo Brasileiro. Disponível em: <http://www.cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/am/apui>. Acesso em: 21 abril 2019.

SILVA, M. D.; PORTO, A. Nas Trilhas do Ensino de História. Belo Horizonte: Rona, 2012.

VEER, R. V. D.; VALSINER, J. Vygotsky uma Síntese. 7. ed. São Paulo: Loyola, 2014.

VIGOTSKI, L. S.; LURIA, A. R.; LEONTIEV, A. N. Linguagem, desenvolvimento e aprendizagem. Tradução de Maria da Penha Villalobos. 16. ed. São Paulo: Ícone, 2018.

ZUCCHI, B. B. O Ensino de História nos Anos Iniciais do Ensino Fundamental: teoria, conceitos e uso de fontes. São Paulo: SM Ltda, 2012.

APPENDIX – REFERENCE FOOTNOTE

3. An excerpt from the Master’s Dissertation of the Master’s Course in Educational Sciences, held at Universidad Del Sol, in San Lorenzo Py.

4. Exame Nacional do Ensino Médio (ENEM).

[1] Doctoral student in La Educación pela Universidad Del Sol – Py, Master in La Educación pela Universidad Del Sol – Py, Specialist in Environmental Education from UCAM, Specialist in Historiography of the Amazon from TÁHIRIH, Graduated in Normal Superior from Universidade do Estado do Amazonas, Licensed in History, Letters and Literature by UNIASSELVI and Vocational High School – Teaching. ORCID: 0000-0002-8316-9404.

[2] Advisor. PhD in Education Science from the Universidade San Lorenzo (UNISAL), Master in Mathematics from the Universidade Federal do Amazonas (UFAM), Graduation in Mathematics from the Universidade Federal do Amazonas (UFAM). ORCID: 0000-0003-0587-7277.

Sent: August, 2022.

Approved: October, 2022.