ORIGINAL ARTICLE

DENDASCK, Carla Viana [1]

DENDASCK, Carla Viana. Action research and its contributions to methodological science: general aspects. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year. 06, Ed. 11, Vol. 11, pp. 118-135. November 2021. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access Link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/education/methodological-science, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/education/methodological-science

SUMMARY

Due to the increase in popularity and the possibility of using action research, the instrument began to be used significantly, but with a concept not yet consolidated, the term has been applied in an abstract way, without deep and detailed interpretations of the use in various contexts. It is intended to clarify throughout this article the meaning of the term, and how this type of instrument can be applied in the best way, acting within the sphere of scientific-methodological rigor. The research problem is: what are the possibilities of using action research, its stages and fundamental care? The relevance of the tool lies in the fact that it allows the conduct of a research in a systematized, continuous and empirically based manner. Thus, it will be discussed about the role of theory in action research and the characteristics inherent to its fundamental phases will be pointed out. Some common questions related to the method, such as the participation of the researcher, the social function of reflection, the need to manage the acquired knowledge and ethics in research should be considered. Finally, some action research “models” are presented that can contribute to researchers in methodological choice and organization.

Keywords: Action search, Search Methods, Search Tools.

1. INTRODUCTION

Action research is a type of research that demands, from the participant, an engaged posture (TRIPP, 2005). It is a strategy, in a way, opposed to traditional research, which is considered as “independent”, “non-reactive” and “objective” (ENGEL, 2000). Thus, as the term itself indicates, action research aims to unite research with action, that is, practice. Thus, knowledge and understanding are understood as part of practice, and is then a way to employ research in situations where the researcher also has a practical inclination and wishes to improve the understanding of a theory (KOERICH et al, 2009). The arguments contrary to action research are especially due to the fact that the researcher is involved in the field studied, which would be in line with the assumptions of ethics in scientific research that recommends the exemption of the researcher as part of the process of scientific quality, alluding that this exemption would be responsible for bringing clarity in the arguments of the researcher who would be absent from the tendency in the production of results (TRIPP, 2005; KOERICH et al, 2009).

This type of research arose from the need to overcome an existing gap between the axes of theory and practice. One of its predominant characteristics is that it is a research from which it tries to intervene in practice in an innovative way during the development of the research. It is not just a recommendation that appears in the final stage (ENGEL, 2000). This aspect has been explored especially by programs that aim to promote pragmatism as a final product, such as in the Graduate Programs of Engineering, Business, or even in the Professional Master’s and Doctorate Programs.

One of the first to introduce action research in the academic context was the German psychologist Kurt Lewin. However, already in the 1960s, sociology quickly appropriated the concept (TRIPP, 2005). It was assumed that the researcher should abandon this more passive, isolated posture, thus assuming the consequences caused by the results of his research, and that such results should be put into practice, thus meeting a demand that sought more contribution from the academic context to the practical world (FRANCO, 2005).

This search then arises in the change of theoretical posture, to a practical posture that can interfere in the course of events. In this context, in addition to its applicability in the social sciences and psychology itself, today, its possibilities of use are wide, which justifies the relevance of this study. One of its new possibilities is the use in the area of education, developed as a response to the demands tangential to the implementation of educational theory in teaching practice, that is, in the classrooms (ENGEL, 2000). Today, one of the results of action research in the universe of education, can be found through the numerous materials that work with active methodologies, even boosting, so that the concept of active methodology will be incorporated by some researchers as discipline and independent methodology.

As mentioned earlier, theory and practice were not perceived as inherent parts of professional life. Faced with such changes, action research began to be implemented in the most diverse contexts (TRIPP, 2005). The aim is to help researchers and professionals solve the problems that affect their daily work practice, getting much more involved with research (MIRANDA; RESENDE, 2006). With this, in the field of education, values, perceptions and beliefs in the exercise of teaching-learning were evaluated empirically (ENGEL, 2000). It is understood that this type of research has been viewed with good eyes by the most diverse academics. It is an attractive research because it leads the researcher to a specific and immediate result in relation to a certain research problem (GRITTEM; MEIER; ZAGONEL, 2008).

It is mentioned that action research has proved to be an efficient instrument for the professional development of several researchers. It is pointed out that this process occurs from “inside out”, since part of the concerns and interests of the people involved in the practice of research (TRIPP, 2005). The subjects are involved with issues that foster their own professional development and also personal development. The contrary approach to action research is precisely traditional research, because research takes place from “out into in” (ENGEL, 2000). In this process, canonical, therefore, the researcher feeds his study with the perceptions brought from an external experience, and this experience is collected through certain research tools (such as questionnaires and interviews) (FRANCO, 2005). However, there is no aim to discuss an ideal approach, as they are unique and different proposals. These are two ways of looking at the nature of scientific research.

It is assumed that scientific truths exist in the world outside research, and it is up to the scientist to discover such truths, including the ability to intervene to test such truths. However, in scientific research, it is inferable that there are ways of looking at the nature of a research, so that there are no absolute scientific truths, because all knowledge is provisional and changes according to the historical context in which one lives (MIRANDA; RESENDE, 2006).

Phenomena are observed as well as interpreted according to such historical and cultural particularities. It is also mentioned that the research patterns themselves are subject to change, because science evolves every day. There is no universal and historical scientific methodology, but distinct ways of looking at the world under scientific bias (GRITTEM; MEIER; ZAGONEL, 2008). Action research, in this sense, approaches a more practical view of everyday phenomena and situations. Thus, scientific knowledge is regarded as provisional and dependent on a context.

Considering the sphere of education, it is understood that teachers, instead of being mere consumers of a research conducted by others, should transform their own teaching practice through the results of this study (ENGEL, 2000). Thus, action research is conceived as the ideal instrument for the execution of a research that wants to unite theory with practice. In this sense, the general objective of this research is, through an exploratory and descriptive study, to reflect on the possibilities of application of action research in any environment of social interaction. The research problem is: what are the possibilities of using action research and its fundamental steps and care? Based on the problem, it aims to verify how an environment in which social interaction occurs and that has a real and urgent problem can benefit from this type of study, an environment that involves people, tasks and procedures that need help.

2. ACTION RESEARCH AND ITS INFLUENCE ON SOCIAL PRACTICE

The literature describes the trajectory of action research since the 1940s. From a broad view, this can be situated in two significant periods: the first is connected to an American current, marked by the emergence of the term coined by Kurt Lewis in the period before World War II (MIRANDA; RESENDE, 2006). This phase lasts until the 1960s. The second moment, in turn, is marked by a European current, current that covers the period from the 1960s to the present day (BARBIER, 2002; MORIN, 2004). The two strands present an overview of this type of research, focusing on the qualitative approach employed by social science research. The concepts, justifications and methodological explanations constructed through theoretical and methodological links demarcated the research carried out so far (BARBIER, 2002; MORIN, 2004).

From this, the notion of intervention arises, and this can vary from a position more linked to experimental studies to social action projects, whose purpose is the resolution of the most diverse social problems (THIOLLENT, 1984). Due to the various concepts and authors who began to discuss action research, several readings and interpretations became constant, leaning now for a more explanatory (experimental) perspective, or for a more comprehensive (phenomenological or dialectical) (TRIPP, 2005). Action research emerges as a criticism, initially, of positivism, even if it is understood that not all have moved away from such understanding. In principle, they are also seen as approaches of a comprehensive nature, because they recognize social reality as something that does not exist or can be recognized as independent and autonomous (FRANCO, 2005). It is, then, a subjective reality and, as such, it is constructed and sustained through individual acts.

It is these individual acts that attribute meanings and meanings to this reality in the process of construction (CARR; KEMMIS, 1988). Among other aspects, it can also be mentioned that there is a parallel between these new rereadings of action research. The French and Canadian approaches, proposed, respectively, by René Barbier (2002) and André Morin (2004), connect. By taking as reference these authors, as well as some of their works, it is not intended to generalize their thinking and form of production of this type of study, but rather to list some of its general elements, because these allow us to understand, in a profound way, the unfolding of action research in the most diverse contexts (TRIPP, 2005). The field of education, as mentioned, is one of the possibilities of spaces in which action research can act significantly. In addition, action research is attributed to a meaning: it is classified as an epistemological revolution (BARBIER, 2002).

It is thus called, because until then, the proposal had not been significantly explored in the field of human sciences. Therefore, it was understood that action research was a kind of “art of clinical rigor” (BARBIER, 2002). Therefore, it can be developed with a collectivity. The objective, then, is to analyze a portion of this society in a less distant, less objective way, as occurs in traditional research, in which neutrality and distancing from the researcher are defended (TRIPP, 2005). However, in order for this type of study to become feasible, it implies a change of the subject’s posture, whether an individual or a social group, with regard to their reality (KOERICH et al, 2009). It is then necessary to provide real perceptions and opinions about a given phenomenon experienced in the day-to-day. The researcher, therefore, captures this phenomenon and records it, uniting these perceptions, values and beliefs of the subject/group analyzed with their theoretical conceptions.

The exercise of action research implies that the researcher has an open systemic view to record the observed phenomena. Therefore, at the time of registration, it must combine certain processes, such as organization, information, perceptions, values, beliefs, with the sources from which it leaves to build its study according to the required scientific rigor (MIRANDA; RESENDE, 2006). The proximity of the researcher of the phenomenon being investigated is one of the aspects that distances the action research from those more canonical, theoretical, only. This happens due to the assumptions that underpin this tool from the moment of its creation (ENGEL, 2000). The pioneer authors in the field, in their studies, criticize the action of positivism in the field of social sciences, since this trend introduced limits to the activity of research, and this began to be based on some pillars, such as objectivity, rationality and truth (KOERICH et al, 2009).

Action research is linked to the idea of constant change and, thus, it is based on the assumption that the actors that constitute reality are also in a constant process of transformation (TRIPP, 2005). In view of this mentality, the need arose to think about the concept of research together with action, that is, to practice, and, with this, we began to reflect on the strategies of solving social problems from another approach (FRANCO, 2005). In this context, studies that choose this research approach reconcile the fields of practice, social action, with the theoretical, epistemological. The practice, that is, the action, concerns everything that is constituted and maintained in a given context and, with this, also covers the action and daily experience of a subject (GRITTEM; MEIER, MEIER, MEIER. ZAGONEL, 2008). Action research is more than a methodological approach. This is a position in the face of essential epistemological issues, such as the relationship between subject and object, theory and practice.

3. CHARACTERISTICS OF AN ACTION RESEARCH

The action research encompasses an empirical process, which allows the identification of the problem within a social and/or institutional context, the collection of data regarding the problem in question and the analysis of the meanings and meanings attributed to the data related to the participants (TRIPP, 2005). In addition to identifying the need for change and surveying the possible necessary solutions, action research also intervenes in the practical environment, as it provokes and drives transformation (ENGEL, 2000). It is a methodological tool capable of combining theory with practice through an action that aims at the transformation of a given context, that is, a certain reality (MIRANDA; RESENDE, 2006). The action research, then, allows associating, to the research process, the possibility of learning, since it demands the creative and conscious involvement of both the researcher and the other members of the research (ROLIM et al, 2004).

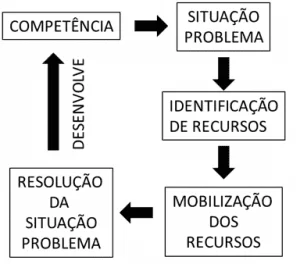

In this context, the importance of action research emerges as a multidisciplinary instrument, since, at the same time, it operates in several fields, such as in the health sector, in the field of education, in the environments marked by innovation and change, among others (TRIPP, 2005). Different groups can be contemplated, such as professionals, managers, students and the general population, both in communities and institutions (ROLIM et al, 2004). There are some characteristics that demarcated action research, such as the conceptualization of the problems that will be worked, the planning, execution and evaluation of actions to solve them. There is, then, the repetition of this cycle of activities (ANDRÉ, 2000). In addition to his notorious social contribution, Lewin’s work on action research was considered innovative, as it promotes, at the same time, the participatory and democratic character, since the research develops from the participation of the subjects studied (TRIPP, 2005).

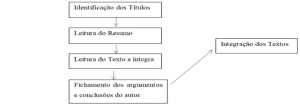

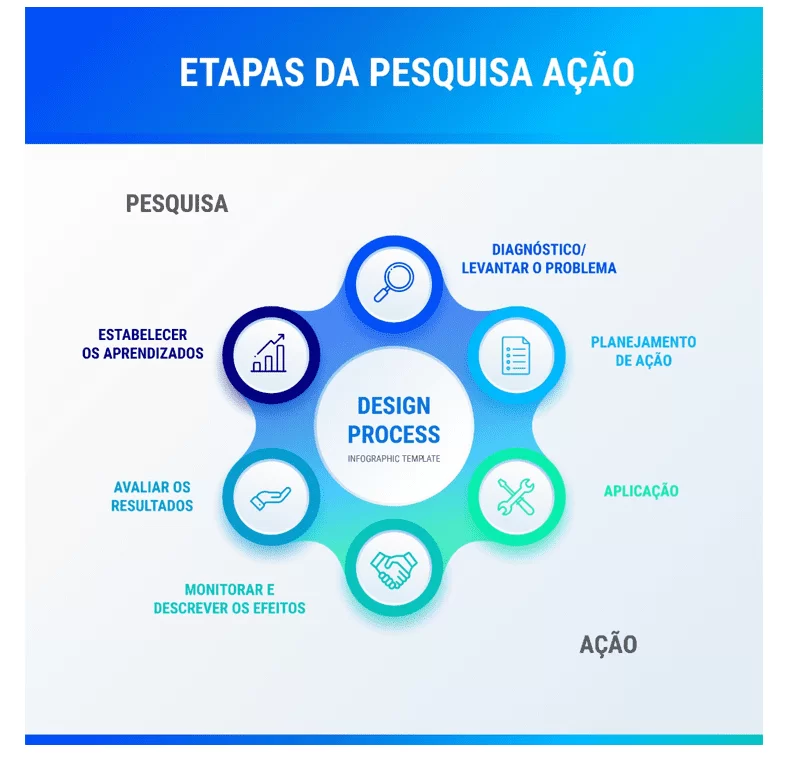

The action research will adopt the following processes in its construction:

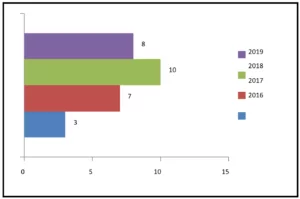

Table 1- Action Research Steps

Therefore, there is a study aimed at solving problems that affect a given environment, focusing, therefore, on the specificities of this context, where these problems manifest themselves (PEREIRA, 2001; LEWIN, 1946). Another characteristic of this type of research is the concern with the scientific validity of the results obtained from the collaborators. In this process, diagnoses are considered, as they point out the situation before and after the use of certain actions, as well as allow the detailed recording of all events (LEWIN, 1946). The understanding of the research instrument discussed here is related to two fundamental concepts, being the act of investigation and the substantive act. The act of investigation is an action capable of boosting and fostering an inquiry (TRIPP, 2005). The noun act, in turn, is an action capable of promoting a desired change in a given context observed and studied.

It is, therefore, a process that unites research to action (KOERICH et al, 2009). In this sense, in the action investigation, the acts are necessarily characterized as substantive. Therefore, due to this qualification, the act of investigating presupposes an obligation, which is the need to benefit people who do not belong to the scientific community, but can benefit from the results of a scientific study (LEWIN, 1946). Thus, science, from its researchers, assumes a new mission: to make the knowledge produced in universities, whether national or foreign, reach secular society, so that the subjects that make up the most diverse social groups are emancipated (FRANCO, 2005). The action research conceived by Lewin has been used from different ways and with different purposes, giving rise to a broad mosaic of theoretical-methodological approaches.

There are at least three different concepts applied to action research in Brazil. They are classified based on some criteria. The first type is collaborative action research (transformation is requested by the reference group to the research team) (KOERICH et al, 2009). The role of the researcher, in this process, is to be part of a change, made scientific. This is triggered by the subjects who are part of the group (TRIPP, 2005). There is also critical action research. The need for transformation is perceived from the researcher’s initial studies with the group (FRANCO, 2005). When change results from a process that values the cognitive construction of experience, supported by collective critical reflection, in order to emancipate the subjects and eliminate conditions that the collective considers as oppressive, the research assumes an essentially critical character (ENGEL, 2000). There is also strategic action research.

If in the other approaches the transformation is previously planned, without the active action of the subjects, the same does not occur here. If there is only one researcher responsible for evaluating and monitoring the results of the application of the study, the action-critical research loses its critical bias (FRANCO, 2005). In order for critical action research to be characterized in this way, a dip in the praxis of the social group being analyzed is required, whose objective is to extract the latent perspectives that support the practices, that is, the changes are negotiated and administered in the collective (KOERICH et al, 2009). Collaborative action research, in this context, also assumes a critical character (THIOLLENT, 1984). The criticality that emanats from this type of study demands a process of collective reflection on the operational strategies to be adopted. This process considers the subject’s voice, as well as his perspectives. The interest not only in the record and in a later interpretation.

It is an inseparable part of this investigative methodology, so that it cannot be established through linear steps aimed at the method itself, but is organized from situations and facts that emerge in the process and become essential (ENGEL, 2000). The emphasis on the formative character of this type of research emerges, so that the subject should become aware of the transformations that affect both the researcher and the group and the process (TRIPP, 2005). Due to this objective, action research assumes an emancipatory character, so that the subjects involved in the research can free themselves from myths and prejudices that prevent the arrival of the desired changes (BARBIER, 2002). This type of research, over the years, as mentioned, has been influenced by positivist currents, since the dialectic of social reality has been incorporated into everyday life, as well as the points that underpin and sustain the dissemination of a linear critical rationality.

In this scenario, the epistemological status that support action research began to worry about the processes behind social transformation, being committed to the ethical and political aspects related to the emancipation of the subjects, also focusing on the conditions that support the emancipatory process (MIRANDA; RESENDE, 2006). The action research began to admit some interpretative approaches to analysis and received a structure capable of fostering the critical participation of those involved, which caused the research process to admit the reconstructions, as well as the resignifications of meanings and paths throughout the execution of the stages (TRIPP, 2005). It assumed a form characterized as pedagogical and political (THIOLLENT, 1984). In the context of qualitative research, there are three dimensions that should be considered by action research. The first of these is ontological. It concerns the nature of the object to be known and investigated by the researcher.

The second dimension is epistemological and concerns the subject who seeks to know. The third dimension, finally, is the methodological dimension, whose objective is to know the processes from which knowledge was constructed by the researcher involved with a certain group (FRANCO, 2005). With regard to the ontological dimension, it can be mentioned that it is linked to a guide knowledge, and this should allow the subjects to produce knowledge for a better understanding of the elements that condition a certain social praxis (KOERICH et al, 2009). The purposes of this research are desired by the collective itself, which demands, from the researcher, the need to produce knowledge that can allow the restructuring of certain formative processes (FRANCO, 2005). Regarding the dimension of epistemological character, it is mentioned that, for its exercise, the researcher immerses in the intersubjectivity of the dialecticof the collective.

Therefore, the researcher must assume a differentiated posture when dealing with and interpreting knowledge, since, at the same time, he seeks to know and intervene in the reality of that group that is being investigated (ENGEL, 2000). The union between research and action, therefore, causes the researcher to essentially have to enter the researched universe, but this need in no way nullifies the possibility of adopting a neutral posture when dealing with the data, because this is an assumption of science itself (KOERICH et al, 2009). Neutrality is a way of controlling the circumstances that permeate a research, which implies drawing attention to the fundamental epistemological assumptions, such as the prioritization of the dialectic of social reality and the historicity of phenomena, praxis, contradictions, relationships with totality and analysis of the subjects’ action based on some circumstances (KOERICH et al, 2009).

Praxis, in this context, should be conceived as a basic way of constructing knowledge, because, through it, theory and practice are articulated (FRANCO, 2005). With regard to the knowledge to be analyzed, this is not restricted to mere description, because it is up to the researcher to explain such transformations from what he observes, that is, through a movement that integrates the dialectics of thought and action (TRIPP, 2005). As a result, the knowledge derived from this relationship is able to transform the subjects and the circumstances related to the medium of which it is part. The methodological dimension, in turn, demands certain procedures that articulate ontology with the epistemology of action research, which implies establishing in the observed group a dynamic that integrates the dialogical, participatory and transformative principles and practices (TRIPP, 2005). In this dimension, some elements must be taken into account.

Among them, one can mention praxis. It is the starting and arrival point when it comes to the construction and/or resignification of knowledge (FRANCO, 2005). It is based on the notion that knowledge can only be constructed through multiple articulations with intersubjectivity. In view of this characteristic, action research, in order to be well articulated, must be carried out in the natural environment of reality to be researched, so that the results collected are true, safe and of quality (ENGEL, 2000). In this process, there is a certain flexibility, since the goal is to capture a reality in the process of change. Thus, the methodology should be able to allow the researcher to make certain adjustments, and the researcher should walk according to the provisional synthesis. Such summaries are established in the group itself (GRITTEM; MEIER; ZAGONEL, 2008). It is these elements that point out how a certain context has been affected.

The method should involve continuous exercise of cyclic spirals. These spirals take into account some fundamental steps, such as planning, action, reflection, the act of research, resignification and replanning, the latter when necessary (KOERICH et al, 2009). On action research, it is also highlighted that, while an investigative process, education and action happen concomitantly. In this sense, the epistemological and methodological reasons that permeate the investigative activity cause knowledge to be actively produced, because all those involved in the process must collaborate (ENGEL, 2000). The investigation, in this context, makes it possible to understand the changes in reality through action (TRIPP, 2005). The process requires a specific posture from the researcher.

He often comes up with certain types of questions, as well as with some specific demands, such as the insertion in the culture that is analyzing new meanings, meanings, representations, resistances, expectations and experiences (FRANCO, 2005). The challenge that the researcher is up against, in turn, is to make a new environment, in a process of family construction. In other words, change should be perceived by all involved (KOERICH et al, 2009). The researcher is one of the participants of the universe that is being investigated, however, the neutrality of research is a principle that should be considered. Therefore, their perceptions about the analyzed phenomenon cannot be ignored, however, its handling must be done in the appropriate way. One of the objectives that can be achieved through this strategy concerns the achievement, among the participants, of greater confidence (KOERICH et al, 2009).

The action-research cycle starts with the exploratory phase. In it, the diagnosis about reality is made and a survey is elaborated on the context, initial problems and possible actions (TRIPP, 2005). From this, researchers and participants establish the main objectives of the research. These should be linked to the observed field, actors and types of actions in which it is intended to focus on investigative activity (FRANCO, 2005). The theme of the research is defined in sequence. This is delimited from a practical problem related to a search area. This is chosen based on the commitments made between the team of researchers and the subjects that correspond to the situation in question (FRANCO, 2005). However, the theme can also be requested by the actors of the situation. It should be of interest to both researchers and the subjects investigated so that all take an active role and contribute to the development of the research.

It also chooses a specific theoretical framework with which to work, because it will guide all the research. Thirdly, the problems are elected, that is, the research problem. It is from the problem that the theme gains robustness (ENGEL, 2000). The problem should cover some research assumptions, such as the analysis and delimitation of the initial situation; the design of the final situation, based on criteria of disability and feasibility; the identification of all problems to be solved; the transposition of these problems into corresponding actions; and, finally, the implementation and evaluation of actions (TRIPP, 2005). In this sense, it is necessary to adapt a framework of theoretical references to the practical reality of research. The objective is that the information be analyzed and interpreted from a theoretical basis, however, it must be articulated with the real experiences, collected, therefore, from the collaborators of the study (TRIPP, 2005).

So, arrives the hypotheses. Despite the false idea that there are no hypotheses, it is necessary to think carefully about this proposition, which implies understanding the hypotheses as assumptions formulated by the researcher that may or may not be confirmed (KOERICH et al, 2009). The hypotheses admit possible solutions to a research problem and thus aim to conduct a line of thought (KOERICH et al, 2009). The seminar is also one of the phases of action research, as it plays a significant role in the decision-making process in an investigation, as well as provides the coordination of activities. The purpose of a seminar is to define the theme and establish problems with which the research will operate. The elaboration of the problem so that problems are treated, as well as research hypotheses, is one of the objectives. The study groups and research teams that coordinate these activities are born.

The information comes from different sources and groups, which provides access to interpretations that foster the processes of establishing action guidelines, as well as it is possible to evaluate the actions and disseminate the results from appropriate channels (KOERICH et al, 2009). Action research is also operationalized from the fields of observation, sampling and qualitative representativeness. This may encompass a concentrated and/or spread community, however, sampling and representativeness is a factor that can be discussed. Some studies exclude the sample, others recommend its use, others value the criteria of qualitative representativeness (FRANCO, 2005). You enter the data collection stage. The main techniques used are collective and/or individual interviews, conventional questionnaires, the study of files, etc. After the collection of information from the observation groups, they are discussed, analyzed and interpreted together.

4. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The process of investigative activity, reality analysis, as well as evaluation of qualitative tools and methods require a certain dialogicity, that is, it implies the search for reflective knowledge and firming of a commitment to concrete reality. In other words, it requires an effective recognition of the subject and the reality under analysis from a dynamic movement between the parties involved in the investigation. This circular and dynamic possibility lies in the resonance and support for the conquest of a new space and/or the conquest of a new knowledge. Thus, action research as a methodological tool analyzes human action from a communicative and participatory movement, which favors the sharing of knowledge and the elaboration of a relational structure of trust and commitment to the subjects that integrate reality to be transformed. Its object is the resolution or clarification of the problems involved in the group.

During the process, there is a need for continuous monitoring of decisions, actions and all intentional activities developed by the actors involved in the situation. Therefore, under this approach, the research is not limited to a form of action, only, because it aims to increase the knowledge of researchers, as well as their level of awareness, about the people and/or groups involved. The research promotes much more than a data collection and/or propositions of practical interventions. In addition to the considerations presented here, it is emphasized that action research, among other issues, aggregates real, current and coherent discussions and explanations that enable the generation of descriptive knowledge, however, critical, about the situations experienced in various social environments. It promotes, therefore, new forms of expression and reflection about the meanings and feelings of the participants attributed in the analysis of the problem situation in question.

REFERENCES

ANDRÉ, M. E. D. A. Etnografia da prática escolar. Série Prática Pedagógica. Campinas: Papirus; 2000.

BARBIER, R. A pesquisa-ação. Tradução Lucie Didio. Brasília: Plano, 2002.

CARR, W.; KEMMIS, S. Teoria crítica de la enseñanza. Barcelona: Martinez Roca, 1988.

ENGEL, G. I. Pesquisa-ação. Educar em Revista, n. 16, p. 181-191, 2000.

FRANCO, M. A. S. Pedagogia da pesquisa-ação. Educação e pesquisa, v. 31, n. 3, p. 483-502, 2005.

GRITTEM, L.; MEIER, M. J.; ZAGONEL, I. P. S. Pesquisa-ação: uma alternativa metodológica para pesquisa em enfermagem. Texto & Contexto-Enfermagem, v. 17, n. 4, p. 765-770, 2008.

KOERICH, M. S. et al. Pesquisa-ação: ferramenta metodológica para a pesquisa qualitativa. Revista Eletrônica de Enfermagem, v. 11, n. 3, p. 717-723, 2009.

LEWIN, K. Problemas de dinâmica de grupo. São Paulo: Cultrix, 1946.

MIRANDA, M. G. de.; RESENDE, A. C. A. Sobre a pesquisa-ação na educação e as armadilhas do praticismo. Revista Brasileira de Educação, v. 11, n. 33, p. 511-518, 2006.

MORIN, A. Pesquisa-ação integral e sistêmica: uma antropopedagogia renovada. Tradução Michel Thiollent. Rio de Janeiro: DP&A, 2004.

PEREIRA, E. M. A. Professor como pesquisador: o enfoque da pesquisa-ação na prática docente. In: GERALDI, C. M. G.; FIORENTINI, D.; PEREIRA, E. M. A. (Org). Cartografias do trabalho docente: professor(a) – pesquisador(a). Coleção Leituras no Brasil. Campinas: Mercado das Letras, 2001. p. 153-81.

ROLIM, K. M. C. et al. Mulheres em uma aula de hidroginástica: experenciando o interrelacionamento grupal. Revista Brasileira em Promoção da Saúde, v. 17, n. 1, p. 8-13, 2004.

THIOLLENT, M. Notas para o debate sobre pesquisa-ação. In: BRANDÃ O, C. (Org.). Repensando a pesquisa participante. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1984. p. 82-103.

TRIPP, D. Pesquisa-ação: uma introdução metodológica. Educação e pesquisa, v. 31, n. 3, p. 443-466, 2005.

[1] Theologian, PhD in Clinical Psychoanalysis. He has been working for 15 years with Scientific Methodology (Research Method) in the Scientific Production Guidance of Master’s and Doctoral students. Specialist in Market Research and Research focused on health. PhD student in Communication and Semiotics (PUC SP).

Submitted: November, 2021.

Approved: November, 2021.