ORIGINAL ARTICLE

ASSOLINI, Filomena Elaine Paiva [1], GARRIDO, Caio [2], BARTHOLOMEU, Josiane Aparecida de Paula [3]

ASSOLINI, Filomena Elaine Paiva. GARRIDO, Caio. BARTHOLOMEU, Josiane Aparecida de Paula. The teacher as the founding subject of a discourse. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year. 07, Ed. 07, Vol. 04, p. 45-66. July 2022. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access Link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/education/teacher-as-the-founding, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/education/teacher-as-the-founding

ABSTRACT

Founding a discourse implies thinking for oneself and being an author not interdicted by a prior structure of power. Therefore, this article adopted as a central ist: how does the power structure influence the construction of one’s own thought, especially in the construction of a pedagogical discourse by the teacher? Aiming not only to seek the answer to this question and understand it, but also, from the concepts of subject and authorship, to think about how the readings and affiliations of discourse and meaning create or prevent the existence of a thought of its own and unbound from a mere structure of power. Therefore, for the research, the theoretical fields of affiliation were Discourse Analysis (DA), the Socio-Historical Theory of Literacy and freudo-lacanian psychoanalysis. In addition, there was a survey conducted with about 35 subject-teachers who teach classes in state and municipal public schools in Ribeirão Preto and neighboring cities, which were interviewed, yielding oral and written statements. Thus, the results showed that sometimes the teacher’s identification with a historically constituted socio-pedagogical discourse prevailed, where the presence of displeasure prevailed in the activities, as they were driven by institutional impositions, and sometimes the interpretation and production of meanings and (re)meanings by the subject-teacher prevailed, authorizing themselves in their sayings. Thus, it was found that knowledge and the right to interpretation (to reading) is not shared, but is distributed socially and historically in a non-homogeneous way. Therefore, given the way the interpretation is institutionally administered, authorship is affected by it. That is, in order to be able to occupy the author position, it is necessary to have the right and the possibility to occupy different places of interpretation, to move around them and to constitute as an interpreter. And even more, as an interpreter-historicized.

Keywords: Subject, Speech, Senses, Signification, Resignification.

1. INTODUCTION

The development of this article was based on the fundamental question: how does the power structure influence the construction of one’s own thought, especially in the construction of a pedagogical discourse by the teacher? Therefore, the objective is not only to seek the answer to this question and understand it, but also, from the concepts of subject and authorship, to think about how the readings and affiliations of discourse and meaning create or prevent the existence of a thought of its own and unbound from a mere structure of power.

That said, to think about how the affiliation between certain networks of discourse and meaning is structured, it is necessary to think discursively about the broader circumstances of enunciation in the socio-historical, cultural and ideological context and in the conditions of production of the immediate context in which our sayings occur, having the understanding that the imaginary is necessarily part of the functioning of language. It is necessary to understand that meaning does not exist by itself, but is determined by the ideological positions put at stake in the socio-historical process where words are produced, understanding that they change according to the positions occupied by those who employ them. That is, there is an identity factor at stake there.

In view of this, this research was based on the concept of discursive memory – Pêcheux (1999) and Orlandi (1999) – in Charlot’s writings (2000, 2005) on the subject’s relationship with knowledge, as well as on the Lacanian conceptualization that traumatic events, when repeated, can be re-written in later experiments (apres-coup ), to argue, in the context of this problem, that memory does not go out, but is updated in the discourse and continues to produce and reverberate meanings.

From the discursive point of view, history is understood as a plot of meanings, which is not confused with the chronology of facts, but which is defined as the production of meanings about the real, which determines this chronology, intervening in the constitution of subjects and in the functioning of language.

Exercising teaching responsibly implies the understanding that the meanings of postmodern society are constituted from power relations.

Therefore, the importance of a subject-teacher being an interpreter-historicized, becoming a subject producing meanings capable of interpreting the world unbound from the senses imposed by certain preexisting power structures is defended. It is a basic condition for this professional, since he has the responsibility and challenge of educating children and young people in contemporary society, characterized by uninterrupted and rapid socio-historical, cultural, scientific and technological transformations. Thus, “the concept of interpreter-historicized […] it is based on the postulates of the AD and also, in the Discursive-Deconstructivist perspective, proposed by Coracini (2003, 2010)”, (ASSOLINI, 2018).

Thus, it is understood that, by conceiving reading as an interpretation, as Pêcheux (1997) and Coracini (2014) propose, it is possible to counter the idea of reading understood as decoding, which is one that seeks only meanings already known and legitimized.

To mark this opposition means to offer valuable opportunities to reverberate other meanings in the classroom and in school, to which no limits have been placed resulting from ideological formations, where questions and games with language and neologisms formulated by the children themselves, for example, are usually not heard, recognized and much less valued.

One can visualize the question of the recognition and appreciation of language creation by children in the following example: a two-year-old baby, when hearing the sound of the discharge in the bathroom, formulates the following neologism to its mother: “Bye poop”. Repeated on other occasions, it acquires the status of creating a new word, because it is clear that the child understands that expression as a noun, thus producing new meanings. New senses, because the action that was previously only presented as a “give the discharge”, gained a whole new affective and symbolic contour for the child. Thus, since this new denomination is not barred, this movement becomes a way to get out of the legitimate circuits of right to self-discourse. Which makes us have a lot to learn from the kids.

The discourse, always produced in a space of networks and socio-historical affiliations, always maintains a relationship with other sayings and, therefore, is not a homogeneous entity.

In this context, the analyses indicate that the subjects-teachers, whose discursive memories relate positive affections to their experiences with reading, develop pedagogical practices that enable the student to occupy the position of a subject who dares to produce meanings, which is a great step, because, as demonstrated in other studies (ASSOLINI, 2003, 2013), in elementary school still in force the DPE[4] (School Pedagogical Discourse) traditional, that imposes on the student the condition of repeater of meanings that affect little or meanings with which they do not identify.

However, on the other hand, experiences with reading associated with displeasure, interdiction, mandatory and difficult situations, when not resignified, contribute to the identification of the subject-teacher with the discursive formations predominated by the dictates of the traditional DPE, covering the assumptions that there is the ideal model of being human, with certain intellectual, physical and moral virtues; and that the subject-teacher is the center of the teaching-learning process, where it sometimes ends up assuming an authoritarian discourse and clinging to the reproduction of archaic teaching practices, considered as unquestionable.

Cases such as this, where the subject-teacher is anchored in the DPE and in the authoritarianism resulting from it, brings to the reflection the fact that knowledge is not shared, but socially distributed. It can be said that since the Middle Ages, as in Greek antiquity (Hellenistic society), there was a clear separation between those who had access to cultural goods and those who could only alam and idolize them. From this perspective, Certeau (1999) says that

A utilização do livro por pessoas privilegiadas o estabelece como um segredo do qual somente eles são os “verdadeiros” intérpretes. Levanta entre o texto e seus leitores uma fronteira que para ultrapassar somente eles entregam os passaportes, transformando a sua leitura (legítima, ela também) em uma “literalidade” ortodoxa que reduz as outras leituras (também legítimas) a serem apenas heréticas (não “conformes” ao sentido do texto) ou destituídas de sentidos (entregues ao ouvido). (CERTEAU, 1999, p. 255).

In other words, it is necessary to untitude the idea that there is a true interpretation, or the true interpreter and unlink ing that from the positions of power, which would be the positions authorized to speak, to direct a speech and to have a true relevance in relation to what it says.

Occupying this position, that of an interpreter-historicized subject (ASSOLINI, 2003, 2013), that is, that of a subject who is authorized to speak, to produce other readings and to retell stories, contributes to the subject-teacher learning that he can establish with reading relationships characterized not by interdiction, but by the understanding that the senses are not finite, limited and much less evident.

In this respect, when we talk about interdiction, we are talking about censorship, since it is the “[…] prohibition of the subject’s inscription in certain discursive formations, that is, certain meanings are prohibited because the subject is prohibited from occupying certain places, certain positions” (ORLANDI, 1992, p. 107).

When the teacher allows himself to reach the place of producer of meanings, being able to transgress the place defined by a previous power structure, he begins to occupy the teacher position, which, consequently, recognizes the students as subjects, who have the right to occupy the place of interpreters.

In this context, the mechanisms of production of the senses imply a symbolic relationship of the language with the imaginary, in a process where the different discursive formations align in network to the senses and subjects.

2. THEORETICAL ASSUMPTIONS: CENTRAL CONCEPTS

For this research, the Theoretical Fields of Affiliation were the Discourse Analysis (DA) of the French Matrix (Pecheuxtian), the Socio-Historical Theory of Literacy and freudo-Lacanian Psychoanalysis.

In this aspect, The DA promotes significant displacements in the ways of reading (interpreting) and analyzing the text and discourse, as well as in ourselves, as subject-researchers.

The Socio-Historical Theory of Literacy, in turn, allowed us to understand that writing is associated, from the beginning of time, with the game of domination/power, participation/exclusion, which ideologically characterizes social relations, especially in an unequal society like ours, as well as to understand that literacy and literacy are processes that do not end, that oral linguistic manifestations can also support the development of a process of authorship and that the oral discourse of the unliterate subject may be permeated by characteristics of the written discourse.

On the other hand, Freudian-Lacanian Psychoanalysis is interesting, mainly due to the conceptions of après-coup, according to Lacan, and a posteriori, according to Freud, including subjectivity, subject, transference, among others, which make it possible to realize more well-founded and in-depth discursive analyses.

And the Psychoanalysis that Bion brings, is interesting because of his specific and special theory of thought and “thinking”, which makes possible the reflection on the “thinking for oneself” or the “own mind”.

In this context, the question of the unconscious shows that language is opaque and slippery and that there is no purification capable of making it clear and transparent.

2.1 CONCEPT OF INTERPRETATION

It is necessary to undertake a brief reflection on the notion of interpretation, in order to clarify that the discursive perspective assumes that man, as being symbolic and historical, “[…] is condemned to mean” (ORLANDI, 1996, p. 38), because, in view of any symbolic object, the subject has the need to “give” meaning (ORLANDI, 1996, p. 64).

In the discursive approach, the interpretation is not seen as a simple gesture of decoding, of apprehension of meaning, because there is no way to “capture” the meaning(s), since it(s) does not emanaise(m) from words.

In this context, The DA situates interpretation in the relationship with ideology and this, in turn, is conceived “[…] as the process of producing an imaginary, that is, the production of a particular interpretation that would appear, however, as the necessary interpretation that attributes fixed meanings to words, in a historical context” (ORLANDI, 1992, p. 100).

Thus, it can be affirmed that the interpretation is not free of determinations, it (the interpretation) cannot be any, it cannot be arbitrary, because every gesture of interpretation is characterized by the inscription of the subject and his/her saying in an ideological position, configuring a particular region in the memory of the saying.

Thus, according to Pêcheux (1997), the right to interpretation (to reading) is socio-historically distributed, so that, from the point of view of social formations, institutions govern the (im)possibilities of interpretation.

Therefore, given the way the interpretation is institutionally administered, authorship is affected by it. That is, in order to be able to occupy the author position, it is necessary that the subject can, rather, have the right and the possibility to occupy different places of interpretation, move around them and constitute himself as an interpreter. That is, that he can go through processes of identifications, and not find himself arrested, fixed and determined in some identity given by another.

Therefore, it is considered pertinent to think and discuss about the subject’s (im)possibilities to occupy a position that allows him to intervene in the process of producing meanings. To be able to occupy a social and ideological place and feel authorized to say, interpret and produce meanings from that place.

2.2 AUTHORSHIP: SOME BASIC QUESTIONS

It is also necessary to consider the history of the constitution of the senses in writing and orality, in addition to the role of memory (historical and particular).

Considering that the subject can also be an author in oral discourse broadens the understanding of the literacy phenomenon, allowing to include in the question the oral discourse of non-literate subjects, who live in literate societies. In the same direction as Tfouni (1995, 2001), Assolini (2003, 2010, 2013) shows that the principle of authorship is in oral discourses of children who still cannot read and write. With this understanding, the target of interest on the issue is no longer related only to the development of skills and skills related to reading and writing; it launches the challenge of describing literacy within a conception of social practices that interpenetrate and influence each other, whether these oral or written practices.

In this context, being the literacy “[…] a process whose nature is socio-historical” (TFOUNI, 1995, p. 31), it is necessary to accept

[…] que tanto pode haver características orais no discurso escrito quanto traços de escrita no discurso oral. Essa interpenetração das duas modalidades inclui, portanto, entre os letrados, também os não alfabetizados, e aquelas pessoas que são alfabetizadas, mas têm baixo grau de escolaridade. (TFOUNI, 1995, p. 42).

As a result, the principle of authorship is pointed out “[…] characteristic of the organization of the written text”, but “[…] there are discursive linguistic characteristics that are pointed out as exclusive to writing, which, however, are present in the oral discourse of the illiterate” (TFOUNI, 1995, p. 45). Thus, for Tfouni (1995), authorship occurs not only in written discourse, but also in oral discourse.

The discursive approach to literacy, proposed by Tfouni (1995), brings to the discussion the fact that it is no longer the language that should be considered as a parameter, “[…] but the discourses that support the literate practices” (TFOUNI, 2001, p. 82). From this perspective, the dichotomy oral language/written language no longer serves.

Thus, as shown in clipping 1 of the discursive analyses, rescuing the words spoken by professor C, it can be visualized that there is present both orality in the transmission of a discourse, in the transmission of meanings, as well as authorship – which is independent of the discursive matrix that came from the grandmother who, in turn, was illiterate. In this respect, the authorship appears when the stories that the grandmother told were retold and recreated in a new way.

The action of retelling stories allows the subject to resign them according to his discursive memory, which allows him to rescue all sorts of senses, even the erased and silenced (censored).

That said, Freudian-Lacanian Psychoanalysis presupposes a subject of the Unconscious and, therefore, a singular subject. When thinking about the singularity of the subject, it deconstructs the illusory homogeneity of the classroom and a group of students, refutes unique pedagogical models and programs, highlights the subjectivity of the student and the educator, gives theoretical support to understand that we are the result of the discourses that compose us and provides theoretical principles to understand that we are able to resignify situations, feelings and aggressions that we cannot deal with.

It is a process that binds permission, authorization, not censorship or interdiction.

Bringing up grada Kilomba’s “memórias da plantação” again, with regard to the act of writing, she says that: “This passage from object to subject is what marks writing as a political act”. Therefore, writing, according to the author, is a way to “become subject” (KILOMBA, 2019, p. 28).

Thus, it is concluded that they are facilitators in the resignification of their own history, which makes it possible to understand history itself and collective history and, thus, to access this place of interpretation and authorship in the world.

3. METHODOLOGY: CONSTITUTION OF THE CORPUS

Considering that writing allows the subject to distance himself from everyday life and that the cooling of censorship and, still, the meaning of himself, in many cases, affects identity movements, making them flow, it is possible to understand the oral and written statements of the subject-teachers as a way of speaking of themselves, of their experiences, emotions, feelings, anxieties, in short, of expressing their subjectivity.

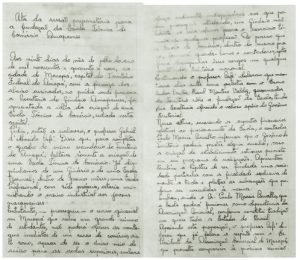

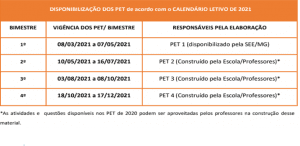

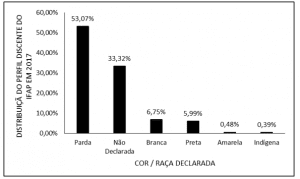

For this, this research had the participation of 35 (thirty-five) subjects-teachers who teach classes in state and municipal public schools in Ribeirão Preto and surrounding cities, who responded to semi-structured interviews and gave oral and written statements about their relations with reading and writing, as well as about their school pedagogical practices, developed in the early years of elementary school. Thus, for this article, three sections of two teachers were chosen, with contrasting discourses, thus being able to support this research.

Having said that, it is appropriate to mention that, according to the theoretical-methodological framework, these teachers were chosen as “subject position”, in this case, “subject-teacher position”. Therefore, the position they enunciate and not issues such as name, age and other sociological aspects was observed and analyzed.

Thus, from the theoretical perspective of DA, linguistic materiality was considered in the convergence between linguistics, ideology and unconscious.

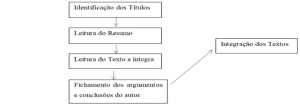

Dealing with methodological aspects, however, supposes to theorize again, because, in DA, there is no single model that could be applied in an undifferentiated way to any discourse. The methodology, thus, is constructed in a continuous movement between theory and analysis, called by Pêcheux (1999, p.50) as “beat”, where the research questions determine the methodological procedures necessary for the analysis of the discourse that constitutes the discursive corpus.

Therefore, it is important to say that this study used the indicia paradigm, as proposed by Carlo Ginzburg (1989), because the marks and linguistic clues that will allow to enter the core of the intradiscourse that, in turn, will lead to the understanding of the discursive formations and ideological formations they project will be indicated. The analyst’s listening is, therefore, a resource from which one cannot give up, and it is up to the discourse analyst to listen to the silences, ellipsis, unspoken and meanings constituted from the discursive formations in which the subject is included, referring them to the ideological formations that are corresponding to them.

Thus, in the methodological process, the interdiscourse and intradiscourse relationship will be considered:

Ao trabalharmos com o interdiscurso, consideramos os já-ditos, as redes de filiação de dizeres aos quais o sujeito se associa para dizer o que diz, a historicidade dos sentidos e seus vínculos político-ideológicos. Em se tratando do intradiscurso, consideramos o fio do discurso, isto é, o que estamos dizendo naquele momento, em determinadas condições de produção (ASSOLINI, 2019, p. 31).

4. RESULTS: LISTENING BEYOND APPEARANCES

4.1 CLIPPING No. 1

| “Nossa, já faz tanto tempo, mas parece que foi ontem […]. O meu irmão era uma ‘peça’, ele recontava as histórias que minha avó nos contava…, quero dizer, recontava tudo de outro jeito, e eu também, porque eu o imitava, e a minha tia dizia: ‘mas vocês são demais, hein?’”

“Pra nós, ler era como brincar, os livros eram sim para ler, mas também para nossas brincadeiras de criança de escolinha, professor, aluno”. “Posso te dizer que tinha sim muita magia, muito encantamento naquela simplicidade toda. Mas a minha avó, mesmo sendo analfabeta, levava a gente para outros mundos” (Sujeito-professor C). |

Considering that the interdiscourse corresponds to the meaning “já-lá“, to “isso fala“, and demonstrates the memory of discursive formations, in addition to the domain of knowledge (ORLANDI, 1992), it can be pointed out that this discourse presents marks and indications of relations with the practice of reading, where it was perceived, felt and treated as a space for the production of meanings. There are also traces that allow us to realize that, in that period of his life (childhood), in those conditions of production, the subject-teacher C occupied the position of interpreter-historicized, saying: “o meu irmão era uma ‘peça’, […] recontava tudo de outro jeito, e eu também, […] e a minha tia dizia: ‘mas vocês são demais, hein?‘”.

Occupying this position, that of an interpreter-historicized subject (ASSOLINI, 2003, 2013), that is, that of a subject who is authorized to speak, to produce other readings and to retell stories, from his discursive memory, allowed the subject-professor C to understand that he could establish a relationship with reading characterized not by interdiction, but by understanding the infinity of the senses. The literate practices experienced by professor C, including listening to the stories told by his aunt, picking up and handling the books and looking at the mother reading the letters, helped him to build his interdiscourse related to reading practices since his childhood, in which the significant “magic”, “enchantment”, “child’s play” and “other worlds” refer to pleasant and instigating situations and senses with reading.

4.2 CLIPPING No. 2

| “Ler, para mim, sempre foi uma chatice, motivo de desgosto, principalmente na infância, porque minha mãe dizia, ou melhor, obrigava a gente a ler a Bíblia todos os dias. […] Agora, quando a gente perguntava alguma coisa, quando queria saber mais… isso era uma afronta… A gente via pelo jeito dela que não podia perguntar nada… que tinha que ficar quieta… bem calada… Tinha que engolir as histórias da Bíblia do jeito que ela falava, porque senão íamos para o inferno. Eu já sabia disso com oito anos de idade” (Sujeito-professor D). |

For subject-professor D, the experiences with reading in childhood refer to memories in which meanings related to “mandatoryness”, “imposition”, “sin”, “boredom” and “disgust” are present.

In the discursive formations in which he was enrolled, in his childhood, the subject-professor D was practically obliged to accept the interpretations imposed on him by the mother, who occupies the position of regulatory subject and controller of senses; “guardian” of the senses that should necessarily be attributed to biblical stories.

Thus, subject-teacher D learned from childhood that he should not dare to interpret, because questions, questions or other readings were treated, by the mother-subject position, as depreciation to the Holy Scriptures. Subordinated, this situation imposed on the subject-teacher the values and norms of the Catholic Church.

Moreover, it is observed that, regarding linguistics, the testimony of the subject-teacher showed many signs of reticence, which allowed us to infer that more memories could still be narrated. However, it seems that subject-teacher D did not desire or be able to carry out the action of resemaring experiences that, according to our interpretation, aroused unpleasing feelings.

In this context, the analysis of this testimony brings clues and traces of an interdiscourse in which the interdiction overlapped with the interpretation.

Therefore, it is important to clarify that this research was based on a theoretical device that understands the subject by his ideology and his Unconscious. Thus, as much as he tries to master his senses, his flaws, fissures and ruptures will manifest in his speech. As Orlandi (1999, p. 59) points out), “[…] memory is made of forgetfulness, of silences. From unspoken senses, from senses not to be, from silences and silencings.”

In this context, the senses do not happen independently of the subject, because, when speaking, the subject means; and by meaning, the same means (re)meaning (ORLANDI, 2006). Therefore, the processes of signification are characterized by the configuration of the subject and the meaning at the same time, and the mechanisms of production of the senses and the subject are the same.

In this aspect, the psychoanalyst Fabio Herrmann brings something similar when talking about the construction of desire in the subject. Hermann states that the subject is built by default by the rules that organize his emotions. According to him, “they are cultural rules, but they are also rules that make culture, because culture makes and is made in the same movement.” (HERRMANN, 1979, p.71). Thus, speaking specifically of desire, Herrmann says that the construction of desire, like the scaffolding of a building, does not appear; the person is constructed by desire, “because he has integrated himself into the world and the subject in the world, constituting a homologous series that does not allow prominence, which does not highlight it. […] It is the desire that builds subject and object” (HERRMANN, 1979, p.71).

There is no subject other than the signifier, since the signifier always assumes a subject. Significant this is meaningless and, therefore, supposes a subject from the articulation with other signifiers. Therefore, the subject is effect and not origin.

In the context of this analysis, it is noted that Lacan (1966 [1998]) appropriates and subsequently discards and subverts the Saussurian conception of linguistic sign. For the Genebrino master, the linguistic sign is a double-sided psychic entity, meaning (concept) + signifier (acoustic image). Considering that both, significant and meaning, form an inseparable set to some extent, one can understand why circumscriptions in an ellipse make meaning emerge.

Lacan (1998) elaborates a theory of the signifier that has as its starting point the algorithm: S/s. In the writings of the chapter “The instance of the letter in the Unconscious or the reason since Freud”, it is concerned with clarifying the reading of its algorithm: “(…) significant about meaning, corresponding the “about” to the bar that between the two stages” (LACAN, 1998, p. 500). Therefore, considering this trait, giving it bar value, implies privilegiing the pure function of the signifier to the detriment of the order of meaning. By fixing the signifier above the bar and plotting it in capital letters, Lacan (1998) shows that the presence of the signifier in speech is prevalent, because the speaker slides from significant to significant, without fully understanding what he speaks, alienated from the meaning he produces. It is the articulation between the signifiers, constituted in chains, that engenders the process of meaning.

Moreover, the effects of the Unconscious – which is structured as language (LACAN, 1990) – produce a knowledge that is not known. It is, therefore, in the blows of a speech (full word) that the subject of the signifier, the subject of the Unconscious, who does not realize his speech, his lapses, or the meanings he produces, other than the posteriori arises.

In the Brazilian educational system, conceptions are still circulating according to which knowing the language and knowing about the language means “knowing how to read and write correctly” the “our” language. This hegemonic understanding, still in force, reinforces the social prejudice of “knowing how to read and write well”, disregarding, for example, the opacity and misunderstanding of the language and the failure of the language in history. In other words, it is denied that, in its operation, the words give rise to different interpretations, and the poetry and memory of the language are ignored, in addition to the surprises that come from them.

Positioning oneself as an interpreter-historicized requires a break with the illusion of literal meaning or referential effect, which produces the illusion of transparency and neutrality of meanings; it also requires to keep in mind that interpretations are never definitive and, therefore, the subject can risk different interpretative gestures. Thus, the concept of interpreter-historicized is part of the postulate, according to which we all have a knowledge about the language: literacy. Conceived here as a socio-historical process, which is part of a continuum, from which it can be said that there are degrees or levels of literacy and literacy, literacy, in its socio-historical approach, comprises the production of meanings as determined by ideology and the Unconscious (TFOUNI, 1995, 2001).

Considering the level or degree of literacy of the subject is an important action for the subject-teacher, because, in addition to assuming that the subject already has accumulated knowledge about writing and different languages in general, he can recognize and value the interpretative gestures of the students for which he is responsible, and the higher the level of literacy the more areas of meaning will be triggered by the student. In this line of thought, it is opportune to remind the teacher the importance of allowing the most different senses to pass through the classroom, even if at first listening they seem chaotic and disjointed with the theme or task in question, for example.

4.3 CLIPPING No. 3

| “Aqui, na minha sala de aula, a caixa de livros está à disposição. Acredito que uma das coisas que ajuda as crianças desta classe a gostar de ler é que eles pegam os livros que quiserem, escolhem eles mesmo, podem pegar o que tiver vontade” (Sujeito-professor C). |

The emphasis placed by professor-subject C, regarding the possibility of students choosing the books that attract them, brings evidence that the subject-teacher is concerned with promoting favorable production conditions so that the access of students to the collection they have in the classroom is without interdiction or any censorship. It is understood that the verb “can” is used in the sense of “being authorized to”. Thus, authorizing students to choose the books they wish to read and allowing them access to the book box, which is made available, contributes significantly to students learning to get involved with their choices, as well as with the readings and interpretations they perform. The action of the subject-teacher gives clues that his discourse and pedagogical practice are distant from the traditional pedagogical discourse, usually authoritarian, conteudistic and magistrocêntrico. The discursive formations in which this subject-teacher is inscribed refer to ideological formations that distance themselves from discourses and ideologies that conceive the teacher as the absolute owner of knowledge, and may impose definitive, unique, not subject to questioning or refutation.

Therefore, it is advocated that it is the teacher’s task to promote favorable conditions of production in the classroom so that pedagogical work with reading and writing can happen in a pleasurable and effective way, achieving the main educational objectives of the initial years of elementary school: teaching the student to read, write, interpret and produce texts marked by authorship. In addition, a school is idealized that offers students, solidly, high levels of literacy and high levels of literacy. Therefore, we seek pedagogical practices that emphasize the importance of literacy literacy, since the interpenetration of literacy and literacy will enable the student to read and write proficientemente and interpret, knowing that its interpretation is not the only one and that many others are also possible. Thus, it is highlighted that, when developing a teaching that places the student in the position of author of his own saying, the school contributes to the same learn to listen and think about what he says, or omit. It is not possible to train critical citizens, capable of distrusting “unique” meanings, to strange and deconstruct them without investing in the formation of author subjects.

Thus, it can be seen that, according to pêcheux postulates (1997), this subject-teacher moves in the sense of moving from the ideological formations that establish who has and who has no right to read. In the classroom all students can occupy the position of “literati”, that is, subjects who can produce meanings. Therefore, occupying such a position is a great advance, because students, in this position, can move through other areas of meaning, mobilizing their own memories of meanings that certainly have particular meanings for them.

5. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The idea, in these final considerations, is to differentiate the subject who formulates meanings from the one who is only a player of meanings. In addition, it is important to identify when possible degradations and discursive distortions occur from certain affiliations.

In this context, the main question was this article: how does the power structure influence the construction of one’s own thought, especially in the construction of a pedagogical discourse by the teacher? Therefore, we sought, from the concepts of subject and authorship, to think about how the readings and affiliations of discourse and meaning create or prevent the existence of a thought of its own and unbound from a mere structure of power.

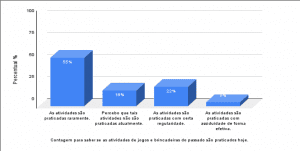

In this context, what was seen in each of the examples presented is that the teacher’s identification with a historically constituted socio-american pedagogical discourse prevailed, where the presence of displeasure prevailed in the activities, as they were driven by institutional impositions (it reads resignation to a previous discourse, of established power, based and limited by censorship, causing interdiction to a discursive construction of its own); and now the interpretation and production (not reproduction) of meanings by the subject-teacher predominated, authorizing itself in his own sayings.

Having said that, it is observed that nowadays, with the advent and abuse of moral discourses, dogmas, delusional beliefs, doctrines of all kinds and ideologies that despise scientific knowledge, with the concomitant insertion in apparently authorized discourses within reality and in a certain structure of power in a society, it becomes difficult to identify the degradations and distortions of meaning, which makes him who wants to formulate his own senses meet many challenges, having to be willing to constantly investigate, without being able to be satisfied in what he reads, thinks or says.

Therefore, through bibliographical research, it was found that it is important to be aware of its historical, ideological and social place, but with the ability to be able to exercise a critical exercise and to be able to doubt methodically, calling into question this very place that occupies, imaginary or factually.

In this context, according to Psychoanalysis, the ability to form thoughts depends on the first relationship established between parents and children, more specifically between the mother (or who does the maternal function) and the baby.

Some important psychoanalysts of the theoretical-clinical history of Psychoanalysis have made great progress in this field, such as psychoanalyst Wilfred Ruprecht Bion who aimed to help the patient give birth to thoughts, since, for him, as well as for Freud, thought is a prelude to action (thought action).

To do so, Bion says there is a thoughtless thinker who needs a thinker to think it. The ability to form thoughts, then, according to Bion, will depend on the child/individual’s ability to tolerate frustration. If this capacity is sufficient, the absence felt can become a thought and, thus, the subject can develop a “device to think”.

This depends greatly on the psychic and biological constitution of the child, but especially on the interaction that takes place between maternal/paternal and child functions. If the subject remains identified with the parents, there will be no room to think, tending to repeat the same speech patterns of these functions. If there is a healthy distance, allowing the subject to become himself, thinking for himself will become more possible. Therefore, all this phenomenon that occurs in early childhood is fundamental to think about the capacity that a subject (and more specifically here the subject-teacher) will have to erect his own building of formulation of senses.

Thus, advancing in time, the relationship he will have with other authority figures he encounters along the way, such as teachers, educators, family members, heads, and the theoretical lines to which he will adhere (as in the case of teachers, in relation to discursive formations that refer to ideological formations of the traditional School Pedagogical Discourse – DPE), will bring the risk of not perceiving in the links of these discourses that exclude him.

For the subject-teacher to constitute himself as an interpreter-historicized, being able to interpret the world, he needs to detach himself from the senses imposed by certain preexisting power structures. Ready speeches and senses and taxes are places of prohibition to thought. Empowerment, accountability and protagonism only happen as these prohibitions and censorships are broken.

Psychoanalysis, as a tool, as well as schools, with their listening and speaking devices, can help the subject to listen. In this sense, could listening to one’s own discourse, by promoting resignifications and reformulations of meanings, be a kind of possibility of becoming a father of oneself? Because what is at stake is fatherhood in relation to what you think: to be an author. Thus, one can be an author of oneself and his world, since life can also be a fiction.

REFERENCES

ASSOLINI, Filomena Elaine Paiva. A relação de sujeitos-professores com a leitura e a escrita: implicações para suas práticas pedagógicas escolares. 2018. 323 f. Relatório de Pesquisa de Pós-doutorado. Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto. Universidade de São Paulo. Ribeirão Preto. 2018.

ASSOLINI, Filomena Elaine Paiva. Interpretação e Letramento no Ensino Fundamental: dificuldades e perspectivas para a prática pedagógica escolar. In: TFOUNI, Leda Verdiani (Org.). Letramento, escrita e leitura: questões contemporâneas. Campinas: Mercado de Letras, 2010. p. 143-162. (Coleção Letramento, Educação e Sociedade).

ASSOLINI, Filomena Elaine Paiva. Interpretação e letramento: os pilares de sustentação da autoria. 2003. 269 f. Tese (Doutorado em Ciências – Área Psicologia) – Faculdade de Filosofia, Ciências e Letras de Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, 2003.

ASSOLINI, Filomena Elaine Paiva. O discurso lúdico na sala de aula: letramento, autoria e subjetividade. In: ASSOLINI, Filomena Elaine Paiva; LASTÓRIA, Andreia Coelho (Orgs.). Diferentes linguagens no contexto escolar. Florianópolis: Insular, 2013. p. 33-52.

CERTEAU, Michel de. A invenção do cotidiano: artes de fazer. 4. ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1999.

CHARLOT, Bernard. Da relação com o saber: elementos para uma teoria. Tradução de Bruno Magne. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas, 2000.

CHARLOT, Bernard. Relação com o saber, Formação dos Professores e Globalização: questões para a educação hoje. Tradução de Sandra Loguercio. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas, 2005.

CORACINI, Maria José Rodrigues Faria. Discurso e Escrit(ur)a: entre a necessidade e a (im)possibilidade de ensinar. In: CORACINI, Maria José Rodrigues Faria.; ECKERT-HOFF, Beatriz Maria. (Orgs.). Escrit(ur)a de si e Alteridade no espaço papel-tela: alfabetização, formação de professores, línguas materna e estrangeira. Campinas: Mercado de Letras, 2010. p. 17-50.

CORACINI, Maria José Rodrigues Faria. Subjetividade e identidade (do) a professor (a) de português. In: CORACINI, Maria José Rodrigues Faria. Identidade & discurso: (des)construindo subjetividades. Chapecó: Argos; Campinas: Unicamp, 2003. p. 239-255.

CORACINI, Maria José Rodrigues Faria; CARMAGNANI, Ana Maria Grammatico. (Orgs.). Mídia, exclusão e ensino: dilemas e desafios na contemporaneidade. Campinas: Pontes, 2014. p. 281-296.

GINZBURG, Carlo. Sinais: Raízes de um paradigma indiciário. In: GINZBURG, Carlo. Mitos, emblemas, sinais: morfologia e história. Tradução de Federico Carotti. São Paulo: Companhia das Letras, 1989. p. 143-180.

KILOMBA, Grada. Memórias da plantação: Episódios de racismo cotidiano. Tradução Jess Oliveira. 1.ed. Rio de janeiro: Cobogó, 2019.

LACAN, Jacques. Escritos. Rio de Janeiro: Zahar, 1998.

LACAN, Jacques. O seminário – livro 11: Os quatro conceitos fundamentais da psicanálise (1964). Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar, 1990.

ORLANDI, Eni Pulcinelli. (Org.). A leitura e os leitores. Campinas: Pontes, 1999.

ORLANDI, Eni Pulcinelli. As formas do silêncio no movimento dos sentidos. Campinas: Unicamp, 1992.

ORLANDI, Eni Pulcinelli. Discurso e leitura. 7. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2006.

ORLANDI, Eni Pulcinelli. Interpretação-autoria, leitura e efeitos do trabalho simbólico. Rio de Janeiro: Vozes, 1996.

PÊCHEUX, Michel. O Papel da memória. In: ACHARD, Pierre. et al. Papel da memória. Campinas: Pontes, 1999. p. 49-56.

PÊCHEUX, Michel. Semântica e discurso: uma crítica à afirmação do óbvio. 3. ed. Campinas: Unicamp, 1997.

TFOUNI, Leda Verdiani. A dispersão e a deriva na constituição da autoria e suas implicações para uma teoria de letramento. In: SIGNORINI, Inês et al. (Org.). Investigando a relação oral/escrito e as teorias do letramento. Campinas: Mercado de Letras, 2001. p. 77-94.

TFOUNI, Leda Verdiani. Letramento e Alfabetização. 1. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 1995.

APPENDIX – FOOTNOTE

4. Discurso Pedagógico Escolar (DPE).

ANNEX (ETHICS COMMITTEE)

[1] Postdoctoral. PhD in Psychology. ORCID: 0000-0002-8433-4862.

[2] Psychoanalyst. He has a degree in Psychoanalysis, and Accounting. Master’s degree in Interdisciplinary Program in Health Sciences from UNIFESP.

[3] PhD in progress in Education. ORCID: 0000-0003-4336-5803.

Submitted: March, 2021.

Approved: July, 2022.