ORIGINAL ARTICLE

ANTUNES, Maria de Fátima Nunes [1], ALVES, Taiane [2], ARCARI, Inedio [3], CARDOSO, Ronan Guimarães [4], GARCIA, Alexandro Ferreira [5]

ANTUNES, Maria de Fátima Nunes. Et al. Reflections on the teaching of Libras in elementary school. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 06, Ed. 09, Vol. 03, p. 05-26. September 2021. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/education/teaching-of-libras

ABSTRACT

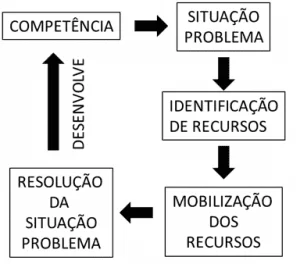

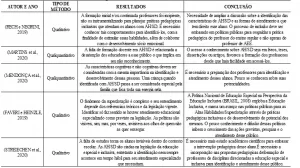

The present work aims to analyze issues inherent to the inclusion of deaf students in regular classrooms in elementary education in our country, as well as the use of LIBRAS in this inclusion process. In this sense, a brief historical account of the inclusion of deaf students is made and definitions and questions inherent to the initial and continuing education of educators are analyzed. In addition, issues inherent to the necessary adaptations in educational institutions for the care of these students are addressed. Finally, we discuss the Brazilian Sign Language (LIBRAS) and its importance in inclusive processes. Given the above, the guiding question is: What adaptations are necessary for the school to promote the inclusion of deaf students? This question guides the reflections of this article. The research is descriptive and uses the bibliographic review method. In this context, the situation of the deaf student in regular education classrooms is explored, according to the literature already published. After analyzing the works that supported the study, it is noticeable that, despite all efforts, care for deaf students is not taking place properly, as few educators know LIBRAS, and are therefore unprepared for such care. It was also found that the curricula and structures do not meet the needs of deaf students.

Keywords: Learning, Written Literacy, Teacher Training, Deaf, Libras.

1. INTRODUCTION

Discussing inclusion is a great challenge, as schools must be transformed into inclusive spaces that provide students with a learning context with more meaning and motivation.

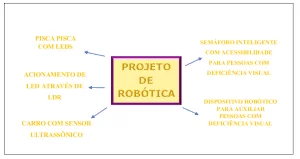

In the education of deaf students, it is necessary to stick to the fact that the mother tongue is sign language. He must become literate like any other citizen and, if he already masters this language, everything flows better; otherwise, educational institutions must promote methods that allow the inclusion of this student, adjusting to their needs. Therefore, for this interaction to actually occur, the use of LIBRAS is extremely valuable, as it provides communication between the deaf and the school community.

Education aimed at the inclusion of deaf students is being adapted in educational institutions, with new methodologies and differentiated strategies, since they are responsible for training teachers, providing them with knowledge related to inclusion, so that they act not only with the student, but also with the family, each having their own responsibility. This joint work improves the performance of the deaf student in the classroom.

The main objective of this article is to analyze issues inherent to the process of educational inclusion of the deaf in regular schools in elementary education, verifying data on the use of Brazilian Sign Language (LIBRAS), as an aid in this inclusive process through already published literature. In this sense, concepts and the history of inclusion are approached with a focus on teacher training and the adaptation of curricula. Given the above, the guiding question is: What adaptations are necessary for the school to promote the inclusion of deaf students? This question guides the reflections of this article.

This research is relevant as it analyzes the situation of the deaf in the school environment, in elementary education, detailing their presence in the classroom, to verify if the situation is indeed inclusion, or if it is just about integration or even segregation. The study also examines the use of LIBRAS, as well as whether the other needs of the deaf are being addressed.

2. CONCEPT AND HISTORY OF INCLUSION

For Peixoto (2002), inclusion is just one of the many ideologies of the capitalist system, being, in most cases, just a way for the state to get rid of its responsibilities. Thus, by using the term “person with special needs”, a way of isolating them in certain social spaces is created. Schneider apud Peixoto (2002, p. 42-43) believes that “if we realize that we help people with special needs to actively manage themselves, we will be helping them to question the very social formation that gave rise to individual conflicts and social conditions imposed on it”.

It is necessary to question deeply the social structure itself. In doing so, one cannot fail to include everyone, without distinction, because not only the exceptional have problems of adaptation, the so-called “normal” are also involved in the process of alienation imposed by the system. According to Peixoto (2002), it is important to take into account the social production of disability and the difficulties of integrating individuals into society, especially those with physical or bodily differences. An egalitarian society would be the ideal state for solving this problem, since the social demands on the individual and the way of relating between them assumed a much more human and healthy dimension. Peixoto (2002) states that the issue of insertion in the regular school system is part of the official discourse, that is, it brings real gains to the public coffers.

Analyzing the historical factor, it is clear that people with disabilities were not well regarded in society, as no one understood their special needs. Thus, society’s behavior towards these people left them powerless and helpless. They were denied access to goods and services, education and living in society, thus setting a serious example of discrimination.

According to Mato Grosso (2002), the practice of inclusion is essential, but for that to happen, social practices are necessary, which aim to respect human diversities, to end exclusion. Thus, the school is indispensable for a dignified education to take place in relation to students with special educational needs. In this sense, adaptations can be planned, which show that the results exceed the teachers’ expectations.

According to the National Guidelines for Special Education in Basic Education (BRASIL, 2002), guidelines and actions that defend and favor Special Education must be created and implemented. Faced with the historical discrimination of these special students, laws related to human rights emerged, with emphasis on the Declaration of Human Rights (UN, 1948), which guarantees the right to education, public and free, for all. In other words, the inclusion of people with disabilities is defended and guaranteed, providing them with equal educational and social opportunities for all, which has contributed to the development of special classes in public schools in Brazil and guaranteeing the right to education for all. Thus, the education of children with disabilities has been gaining strength with the national movement to defend the rights of people with disabilities at school, at work and in the community, with the objective of achieving equality and social justice.

The National Guidelines for Special Education in Basic Education (BRASIL, 2002a) also highlight the Federal Constitution of 1988, which, in article 208, item III, guarantees “specialized educational assistance to students with special educational needs, preferably in the regular network of schools teaching”. Thus, laws emerged to contribute more and more to the inclusion of those who need differentiated education, as well as the appropriate way of knowing more and more about the right of students in the classroom. Equality for all, the right to education, of course, is a valuable milestone that contributes to improving the lives of all citizens.

3. DEAFNESS AND INCLUSION

In Brazil, since the beginning, the educational path taken by the deaf, along with their social influence, has a series of similarities with the path taken by the deaf in the United States and Europe. This situation is due to the general belief that different children were abnormal and therefore should be excluded from social life and the formal education system (STROBEL, 2006).

According to Strobel (2006), the education of the deaf in Brazil, in addition to the original way of viewing the deaf and the European method developed over the 16th to 18th centuries, continued to be influenced from the 19th to the mid-20th century by the development of hearing studies in Europe and the United States. Also, according to the aforementioned author, such research promotes the logic of considering the deaf in Brazil as sick or disabled, in short, as subjects who need specialized treatment and cure.

The classification of the degree of deafness also emerged to point out the size of the hearing deviation of the deaf, in relation to the norms established by society. Affected by these assumptions, Brazil began to systematize and implement specific measures for the education of the deaf, having a normative, charitable and assistentialist character, in institutions dedicated to this purpose. In this context, from the end of the 19th century to the middle of the 20th century, special institutional establishments were maintained, dependent on the work of professional teachers in the area of deafness. It is worth mentioning that, during this period, the deaf group also participated in regular education, but without any special assistance. That is, these students have the opportunity to receive formal education, but they should adapt to the characteristics of this education system instead of trying to meet the expectations and needs of the deaf (STROBEL, 2006).

With regard to the inclusion of students with special needs, Brazilian legislation, in article 208 of the Federal Constitution of 1988, provides that care must be provided to people with disabilities, preferably in the regular school system. In addition, the National Education Guidelines and Bases Act of 1996 also stipulates that education should be integrated as much as possible, and it is recommended that students with special needs be included in the regular school system (LDB, 1996).

Although the laws of the Brazilian education system ensure that students with special needs are included in the formal school system, Mendes (2002/2003) found that there are currently around 6 million children and youth with special educational needs; however, considering special education and general education, the number of enrollments does not reach 400 thousand. Rechigo and Marostega (2002) point out that when education for deaf-mutes is proposed in conventional education, several questions arise. Many question whether this experience can be placed in context without changing the audience’s representation, or if it is more of an experience, a masked terrain, related to rejection.

This process is defined by Skliar (2005) as exclusion and inclusion, that is, in a pluralistic democratic system, the deaf seem to be included; however, exclusion is implemented, in practice, within the school.

To avoid exclusion at school, care is or can be complemented by support services in resource rooms, in different shifts, in hospitals, in the form of home care or in other spaces defined by the education system. From the perspective of inclusion, these aspects are configured as free primary and secondary education.

Education legislation enacted by Law No. 10,098 of 2000 stipulates that the government must take steps to eliminate communication barriers and ensure that the deaf have access to information and education, including training in sign language translation. However, it is observed that, despite the aforementioned laws, most schools and teachers are still not prepared to receive deaf students.

4. QUALIFICATION OF TEACHERS

Special Education around the world is seen as an emergency for everyone, always highlighting the needs that students find in the classroom, having support from people who recognize the importance of Inclusive Education so that it can really happen. With the incentive received from educational bodies, the achievements for students and educators serve as a stimulus to continue the journey in search of dignified and accessible education for all.

It is also known that education is not done alone. Fighting for equality of care and education for students is a challenge for teachers, both in the absence and presence of deaf students in the classroom. Knowing how to give them the necessary and adequate care is a process, it is a path to be followed, which is not, and will not be, easy, neither for the student nor for the teacher. The proposal to be defined by the teacher must be highly qualified, so that the student can be included, present, in all activities inside and outside the classroom.

Within this theme, one can question the concept of inclusion of the teacher in regular education, whether it remains the same or changes throughout the year, after receiving a deaf student. These conceptions can in fact determine the social attitudes in relation to the inclusion of the deaf student in the classroom.

Anjos, Andrade and Pereira (2009, p. 122), when observing the feeling of teachers in relation to the professional theme and the lack of preparation to deal with inclusion, emphasize:

O impacto sentido pelos professores no início do trabalho com alunos deficientes faz com que estes percebam um vazio na sua formação. A falta de um treinamento e o fato de que esses novos sujeitos que estão na sala de aula necessitam de novas capacidades e novos modos de pensar; a certeza de que estão improvisando pode levar os professores a descobrir novos fazeres e novos saberes, não necessariamente subordinados ao ‘fazer correto’; as dificuldades encontradas pelo professor podem ajudar a modificar um projeto pedagógico que, por ter-se tornado automático, tornou-se ‘fácil’. A necessidade que o professor sente de ser instigado, incentivado diante das dificuldades encontradas e dos desafios colocados induziu-os na busca da sua capacitação.

The teacher’s willingness to perceive the student’s transformation from the activities provided in the classroom speaks louder. The perception that this student needs more of your attention points to a gap in their training, motivating them to seek more knowledge to fill the lack of information and knowledge regarding the needs of the deaf student.

Thus, the need for new knowledge and new experiences to be lived instigates the teacher’s will to seek improvement, so that he is able to provide a more advanced and balanced teaching, thus demonstrating coherence between his way of being and teaching, in addition to his accessibility and predisposition towards the integration of deaf students, conceiving it as an extremely important and indispensable factor for obtaining the results.

Gomes and Barbosa (2006) and de Vitta (2010) point out the lack of tranquility of teachers to deal with deaf students. According to them, good training is essential for the good development of students in the classroom. On the other hand, the lack of specific training results in feelings of incapacity for professionals who deal with deaf children. Therefore, teachers must keep themselves informed with content that enhances their professional capacity.

Also, according to Gomes and Barbosa (2006) and de Vitta (2010), working with diversity brings teachers a complex universe to work with the new, as unexpected events can occur at any time. When it comes to training professionals who work in the education and monitoring of students with hearing impairment, the activities must include content that allows the education professional to understand and carry out the proposed activities.

As Dall’Acqua (2007, p. 116) emphasizes, as inclusion takes place in institutional educational organizations, “the process of training special education teachers becomes increasingly necessary and complex”, whether in the definition of their educational roles, whether in the consolidation of pedagogical practices and professional conditions to face a changing reality.

In this perspective, Carvalho (2007) says that the barriers faced with regard to the participation of students in school is a characteristic of them, as it is perceived that there are difficulties even in the maneuvers that must be carried out to keep them included in the school, including involving the pedagogical practice.

As modernas teorias sobre aprendizagem e desenvolvimento humano têm nos apontado inúmeras estratégias, que podem tornar a escola um espaço de convivência agradável, de construção de conhecimento e de apropriação dos bens culturais da humanidade, de forma mais prazerosa, não só para os alunos, como para todos os que trabalham nas, ou para a escola, sejam os educadores, os funcionários administrativos, as famílias e a comunidade (CARVALHO, 2007, p. 124).

To encourage students in the classroom, it is important to carry out activities in groups, which can be passed in class, in order to encourage the desire to learn together and provide the intellectual development of students and the ability to work in harmony. The exchange of information is an important factor for students with hearing impairments.

No que tange ao apoio indispensável aos aprendizes, seus professores e às famílias, a barreira tem sido fazê-los constar dos projetos político-pedagógicos das escolas, não apenas no texto, mas efetivamente funcionando em salas de recursos e/ou com a participação contínua de professores itinerantes, de intérpretes para língua brasileira de sinais ou sob a forma de oferta educacional especializada, fora do espaço escolar, como as classes hospitalares e atendimento domiciliar (CARVALHO, 2007, p. 127).

Deaf students, having appropriate resources for their participation in classes, will break down enormous barriers that hinder their learning. It is up to educators to contribute to eliminating them, ensuring full access for deaf students to schools, with the support of family, teachers and those around them, especially classmates, as it is at school that they must find support for their day-to-day needs and the permanent coexistence of deaf students in schools, without any type of discrimination from peers.

5. AN INCLUSIVE SCHOOL NEEDS ADAPTATIONS

The need to transform into practice the resources that convey the education policy for diversity, used by teachers in the classroom, is based, in a way, on the possibility of the curriculum meeting the different needs of all students. According to Fernandes (2006, p.17), “it is a fact that the school curriculum materializes intentions, beliefs and conceptions considered significant for the formation of students who will benefit from them”.

The institution, first of all, must be concerned with the reputation of its students, offering adaptations that involve the reality of each one of those who attend the school, in order to contribute to overcoming the social inequalities faced by them, that is, to provide more equality for all, respecting differences and valuing students who strive to be successful in their training.

According to Fernandes (2006, p.18), “this curriculum must be the same for all students, because, as citizens, everyone has the right to equal opportunities”. That said, the inclusive school has the characteristic of treating everyone in the same way, but including each one, respecting their uniqueness, offering them full attention, dedication, love, following the school curriculum, but without promoting the exclusion of students with hearing impairment.

According to Fernandes (2006, p. 18), “operational skills to the detriment of intellectual skills for a portion of the population survived for centuries in the elitist proposals that inspire the history of Brazilian education”. The author cites the example of a school that promotes exclusion, by opting for a curriculum in which the pedagogical activities in the classroom demand less from students with disabilities, implying that they are not capable and would not reach the same level as the so-called students “normal”.

A escola para ser caracterizada como inclusiva deve estar preparada com atividades que incluam esses alunos com deficiência. Posto isso, as decisões curriculares devem envolver a equipe da escola para realizar a avaliação, a identificação das necessidades especiais e providenciar o apoio correspondente para o professor e o aluno. Devem reduzir ao mínimo, transferir as responsabilidades de atendimento para profissionais fora do âmbito escolar ou exigir recursos externos à escola (MEC, 1991, p. 41).

According to the National Curricular Parameters (MEC, 1991), curricular adaptations cannot be seen and understood as an exclusively individual process, or an act that involves only teachers and students. For adaptations to occur, it is essential to increase the pedagogical project, develop the curriculum in the classroom and respect the individuality of each student.

No desenvolvimento curricular dentro de uma escola quando falamos em ação pedagógica, o professor é indispensável, pois é ele que sabe de todas as dificuldades enfrentadas pelos alunos e por ele mesmo em sala de aula, incluindo todos que trabalham para uma escola melhor, não esquecendo os funcionários que merecem ter o seu valor reconhecido também, que sempre estão ali para ajudar no que for preciso para um desenvolvimento correto na escola. Sua importância consiste tanto no que se refere à formação dessas pessoas, através da apropriação do saber, quanto na criação de um espaço real de ação e interação que favoreça o fortalecimento e o enriquecimento da identidade sociocultural (BONETI, 1997, p. 167).

Therefore, the interaction between these students and between them and others around them is an achievement. As an interaction process is created in which different family groups are found, communication occurs, which benefits social and cognitive development, in addition to initiating and consolidating friendships that can last a lifetime. Therefore,

[…] as adaptações curriculares apoiam-se nesses pressupostos para atender às necessidades educacionais especiais dos alunos, objetivando estabelecer uma relação harmônica entre essas necessidades e a programação curricular. Estão focadas, portanto, na interação entre as necessidades do educando e as respostas educacionais a serem propiciadas (MEC, 1991, p. 34).

The work valued by a superior is a way to enhance his performance that stands out among many. This is how you should act with a deaf student for him to feel victorious, that is, the teacher must always prioritize the appreciation of the deaf student’s performance, as he must know the difficulties he faces in the classroom and in living in society.

As necessidades especiais revelam que tipo de ajuda, diferente das usuais, são requeridas de modo a cumprir as finalidades da educação. As respostas a essas necessidades devem estar previstas e respaldadas no projeto pedagógico da escola, não por meio de um currículo novo, mas, da adaptação progressiva do regular, buscando garantir que os alunos com necessidades especiais participem de uma programação tão normal quanto possível, mas se considerem as especificidades que as suas necessidades possam requerer (MEC, 1999, p. 34).

According to the National Curriculum Parameters (MEC, 1991), since the curriculum is an instrument that must serve everyone in a regular school, it can and must be changed to benefit all students, including the deaf, in order to guarantee them personal and social development.

The curriculum is an important tool for the school and for the students, so that they can enjoy and make the most of the pedagogical actions, which constitute the concrete form for the development of each one, in the classroom.

As adaptações curriculares no nível do projeto pedagógico devem focalizar, principalmente, a organização escolar e os serviços de apoio. Elas devem propiciar condições estruturais para que possam ocorrer no nível da sala de aula e no nível individual, caso seja necessária uma programação específica para o aluno (MEC, 1991, p. 41).

With regard to the curriculum, it is always necessary to pay attention to the physical structures of the school, that is, the necessary adaptations for the development of everyone’s learning cannot be left out. Adapting schools is essential for the inclusion process to take place properly, so that students and teachers reach their goals and increase their self-esteem. Therefore, to serve deaf students well, a well-qualified teacher is essential.

In the reflection on this subject, it is important to highlight the interest of these educators in qualifying themselves more and more, so that they are valued by the school community. The result to be achieved by qualified teachers has as a response the acceptance of parents and students. Thus, training benefits both the student and the educator, in terms of experience and learning.

In this perspective, Mantoan and Prieto (2006, p. 56) point out that, in the LDB[6] of 96, art. 58, III, “teachers with adequate specialization at a secondary or higher level are provided for specialized care, as well as regular education teachers, trained to integrate these students into common classes”.

To assist deaf students, the teacher must be specialized, so that he is able to bring to the classroom, different forms of educational and pedagogical activities, in order to make the classroom more dynamic and pleasant for students who need support and assistance help for successful school development.

According to the National Guidelines (BRASIL, 2002a), teachers specializing in special education with an emphasis on deafness are those who have developed skills to identify students’ educational needs, who are able to define and program educational responses for these students, supporting them in the process of learning development.

Adaptations in pedagogical practices for the inclusion of deaf students demand the search for valuing relationships in the school environment. However, it is known that the use of LIBRAS by teachers and interpreters is not enough for inclusion to happen. In this sense, the explanations of (PRÁTICAS, 2011, online):

Não há algo pronto para a educação de alunos com deficiência auditiva, mas, com as contribuições da literatura e com a formação e estudos continuados de professores, podemos conhecer práticas pedagógicas que farão toda diferença para a educação de nossos alunos, garantindo assim um direito que é de todos, o de aprender.

When becoming an educator of deaf students, it is necessary to try to understand their particularities, since they need more attention in the preparation of classes. Therefore, the educator must seek, for better use of the content, strategies so that their students are able to understand what is being communicated. Therefore, the selection of resources is of essential importance, since they are part of the teaching and learning process, being important allies for the practice of special students.

In today’s society, visual media are used a lot in communication, such as television, books, magazines, billboards, etc. Therefore, there are some tools that can be used to help deaf students, so that they understand the topics covered in class. Lacerda and Santos (2013, p. 186) ensure that “to promote the learning of deaf students, it is not enough just to present content in Libras, it is necessary to explain classroom content using all the visual potential that this language has” . LIBRAS is a visual-sign language; therefore, it must be exploited to the fullest in order to effectively achieve the learning of deaf students.

For Sampaio and Freitas (2011), one of the Federal Government’s objectives for 2012 was to meet the needs of special children, providing everyone with access to education, with an inclusive contribution to all public, state, municipal or private schools. However, for real inclusion to occur, it is necessary that everyone can have the same professional chance and perspectives of an academic career, so that everyone can demand their rights and fulfill their duties.

Projects and investments that involve the inclusion of special students are the hope of those who want and need to be seen as normal people, in the sense of having access to education, equal opportunities, rights and justice. In other words, it is a dream to be achieved by many.

According to Sampaio and Freitas (2011, p. 20), “the National Plan for the Rights of People with Disabilities, Viver sem Limites, will invest R$ 1.8 billion, an amount to be invested in actions to promote accessibility in schools and guarantee education”.

Places that accept special students even exist, but, usually, they do not contemplate the correct and adequate adaptations. Therefore, taking projects off paper is fundamental in contemporary times, offering adequate materials and structures that meet the demand of these students.

Generally, the adaptations only cover the places where students travel the most in the school, especially the access ramps and bathrooms, which are also the most sought after by parents and students, in addition to accessibility in classrooms. However, inclusion is not limited to the physical structure in the school and in the classrooms, but also involves a set of articulated actions, since, according to Sampaio and Freitas (2011, p. 20), “it is necessary that there is interest from the parents and that they are committed to keeping their children in school and that teachers are dedicated to educating them.

However, it is common in regular schools to find crowded rooms, which is harmful to the included students. Therefore, it is essential that everyone’s opinion is heard in order to provide help to those who need the school so much. The improvement of classrooms in terms of expansion or accommodation of students must happen quickly and accurately, in order to increasingly provide a favorable performance and the motivation of students to attend school and dedicate themselves to studies.

O programa que atende atualmente mais de 24 mil unidades de ensino pelo Brasil foca o desenvolvimento cognitivo, o nível de escolaridade, os recursos específicos para o aprendizado e as atividades de complementação e suplementação curricular. No plano anunciado pela então presidente Dilma Rousseff, seriam criadas mais de 17 mil salas de recursos multifuncionais (SAMPAIO; FREITAS, 2011, p. 21).

The Federal Government has been committed to inclusive education in schools, seeking to promote the cognitive development of students, offering specific resources to build continuity in professional and social life.

6. LIBRAS KNOWLEDGE AND RECOGNITION

The Salamanca Declaration (1990) recognizes sign language and the possibility of using it for the education of the deaf, as well as the maintenance of special education systems such as special classes and schools (BUENO, 2001). Allied to the Salamanca letter, the structure of Libras, according to Coutinho (2000), is composed of signs that correspond to a word, an idea, or even a phrase. Articles are not used in communication. Libras involves: a composite sign formed by two or more signs, which represent two or more words, but with a single idea, typing (hand alphabet), which is used to express names of people, locality or other words that do not have a signal; the spelled sign, that is, a word from the Portuguese language that, by borrowing, came to be expressed by the manual alphabet with an incorporation of the movement proper to this language. In Libras, verbs are presented in the infinitive.

The bilingual method brings security to the deaf student to communicate with other people and be inserted in society. Therefore, the right to use Brazilian sign language contributed to several states using it.

LIBRAS was not only recognized in the municipalities, but is also supported by the Federal Decree, through Law 10,436, of April 24, 2002b, which provides for the Brazilian Sign Language (LIBRAS). No Art. 1, the Brazilian Sign Language – LIBRAS and other resources of expression associated with it are recognized as a legal means of communication and expression. Sole Paragraph: It is understood as Brazilian Sign Language – LIBRAS, the form of communication and expression, in which the linguistic system of a visual-motor nature, with its own grammatical structure, constitutes a linguistic system for the transmission of ideas and facts, originating from deaf community in Brazil (Decree n°10,436, of May 24, 2002b).

That said, the recognition of Libras is a great achievement, as it has become the official language of the deaf; therefore, the hearing impaired are citizens like any other person, having the same rights to be integrated into society, especially in the context of teacher qualification and in so many other professional contexts involved, so that there is a perfect inclusion at any level of education, from the sensitivity created in the school environment.

With the approval of LIBRAS, other measures were taken to make it a mandatory subject in all undergraduate courses, taking into account the demand of the deaf community for access to education and bilingual care, thus prioritizing the first language of the deaf. Decree 5,626, of December 22, 2005, says, in Art. 9, sole paragraph, that the process of including Libras as a curricular subject must start in the Special Education, Speech Therapy, Pedagogy and Letters courses, expanding to the other degrees (Decree No. 5.626, of December 22, 2005).

For this process to become a reality, it is necessary to streamline and develop projects in which the student is integrated into the school environment, implementing improvements in the education offered to deaf students. In addition, it is necessary to provide teachers with quality continuing education, adapting curricula and implementing new forms that add to the learning process of students with deafness, thus complying with the law that governs a quality educational system.

In this sense, for an effective change in teaching, LIBRAS has been recognized as a path for students with hearing impairments, a recognition that comes from the struggles of years to gain space not only in school, but in society as a whole, for being an element essential for communication and for the strengthening of deaf identity in Brazil. Therefore, the school cannot ignore the students’ teaching and learning process.

According to Quadros and Karnopp (2004), just like spoken languages, sign languages are not universal; each country has its own language. In the case of Brazil, there is LIBRAS. The authors express their concern when it comes to the education of the deaf, due to the fact that LIBRAS is still a language left aside by many, making it difficult to enter the school as a second language for hearing people and as a mother tongue for the deaf. LIBRAS is not just a language, it is characterized by being a visual-manager language, that is, communication is not established through the oral channel, but through vision and space.

Although there is a good number of professionals specializing in assisting deaf students, it is still few, as what is most found in the literature are references to teachers who are unaware of all forms of communication with the deaf person, because, in Brazil, it is still recent offer of initial training in LIBRAS. Thus, the vast majority of educators still do not use this language, which largely prevents communication between peers.

When talking about inclusion, it is necessary to mention the importance of LIBRAS being adequate to the school curriculum, giving full support to the training of specialized teachers, so that they favor the hearing and the deaf, leading them to full inclusion, making teaching appropriate to each student. In this sense, Skliar (2005, p. 27) states that “enjoying sign language is a right of the deaf and not a concession of some teachers and schools”.

The school must adapt to the student, presenting learning alternatives, regardless of their differences, promoting strategies for the Brazilian Sign Language to be their first language. When opting for an inclusive education, the school is responsible for the adequacy of the political-pedagogical project, so that it meets all the students’ needs, as it develops pedagogical practices to be exercised in the school space.

7. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The present research of bibliographical revision was guided in analyzing questions inherent to the inclusion of the deaf student in classrooms of regular education in the basic education system. To achieve the desired objectives, scientific works related to the theme were analyzed.

The Salamanca Declaration (1990) meets the needs of the deaf student; however, no law has been and is capable of actually bringing about the necessary changes at the heart of society. Thus, there are still many deaf people relegated to regular education classrooms, in elementary education, without receiving the proper follow-up, as most educators do not know how to discern between what inclusion and integration are, that is, they seek to integrate, believing whatever to include.

In order for the deaf student to be, at the very least, better received, educators should be trained to carry out this process, since it is not just about the deaf, but rather a classroom, generally heterogeneous, and an educator to mediate this set. If he is not prepared, being at least knowledgeable about LIBRAS, this inclusion is practically impossible. Thus, the deaf is relegated to adapting to the context, which is an arduous and frustrating task for him.

Brazilian educators have not received training to work with this audience. In addition, the inclusion proposal, in a way, is still recent, as well as the government, when closing special schools and inserting deaf students in regular education, did not propose a training with the potential to prepare them. With short and punctual training programs, teachers have been developing, but the process, however, occurs very slowly.

It is noticeable that the curriculum is a useful tool for everyone in the school and can be changed to benefit deaf students in order to guarantee their personal and social development. These curricular changes or adaptations are of paramount importance for inclusion; however, there are educators who believe that non-differentiation in treatment would also be a form of exclusion.

Finally, it is clear that there is still a long way to go before there is a true inclusion of the deaf student in regular elementary education, mainly due to the lack of public policies aimed at this educational context, above all, the lack of training of educators, regarding the use and functioning of LIBRAS, an essential tool for communication with these students and for their inclusion.

REFERENCES

ANJOS, H. P.; ANDRADE, E. M.; PEREIRA, M. R. A inclusão escolar do ponto de vista dos professores: o processo de constituição de um discurso. Rev. Bras. Educ., v. 14, n. 40, 2009.

BONETI, R. V. F. O papel da escola na inclusão social do deficiente mental. In: MANTOAN, M.T.E. (Org.). A Integração de Pessoas com Deficiência: contribuições para reflexão sobre o tema. São Paulo: Memnon, 1997.

BRASIL. Constituição de 1988. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. Brasília: Presidência da República, [2020]. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao.htm#:~:text=I%20%2D%20construir%20uma%20sociedade%20livre,quaisquer%20outras%20formas%20de%20discrimina%C3%A7%C3%A3o. Acesso em: 20 abr. 2021.

BRASIL. Decreto Federal n° 5.626, de 22 de dezembro de 2005. Regulamenta a Lei 10.436/2002 que oficializa a Língua Brasileira de Sinais – LIBRAS. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2004-2006/2005/decreto/d5626.htm#:~:text=DECRETO%20N%C2%BA%205.626%2C%20DE%2022,19%20de%20dezembro%20de%202000. Acesso em: 20 mai. 2021.

BRASIL. Diretrizes Nacionais para educação especial na educação básica. 4. ed. Brasília: MEC, 2002a.

BRASIL. Lei n°10.436, de 24 de abril de 2002b. Dispõe sobre a Língua Brasileira de Sinais – Libras e dá outras providências. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/2002/l10436.htm. Acesso em: 20 mai. 2021.

BRASIL. Lei nº 10.098, de 19 de dezembro de 2000. Estabelece normas gerais e critérios básicos para a promoção da acessibilidade das pessoas portadoras de deficiência ou com mobilidade reduzida, e dá outras providências. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l10098.htm. Acesso em: 10 jan. 2021.

BRASIL. Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Lei de Diretrizes e Bases da Educação (LDB). Brasília: Presidência da República, 1996. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9394.htm. Acesso em: 10 jun. 2021.

BRASIL. Parâmetros Curriculares Nacionais (PCNs): Estratégias para educação de alunos com necessidades educacionais especiais. Brasília: SEF/SEESP, 1991.

BUENO, J. C. S. Função social da escola e organização do trabalho pedagógico. Educar, Curitiba, n. 17, p. 101-110. 2001.

CARVALHO, Rosita Edler; Educação Inclusiva: Com os Pingos nos “IS”. 5. ed. Porto Alegre: Mediação, 2007.

COUTINHO, D. Libras e Lingua de Portuguesa (semelhanças e diferenças). São Paulo: Arpoador, 2000.

DALL’ACQUA, M. J. C. Atuação de professores do ensino itinerante face à inclusão de crianças com baixa visão na educação infantil. Paidéia, v. 17, n. 36, 2007.

DE VITTA, F. C. F. A inclusão da criança com necessidades especiais na visão de berçaristas. Cadernos de Pesquisa, v. 40, n. 139, p. 75-93, 2010.

DECLARAÇÃO DE SALAMANCA E LINHA DE AÇÃO SOBRE NECESSIDADES EDUCATIVAS. Brasília: Ministério da Educação,1990.

FERNANDES, Sueli. Metodologia da Educação Especial. São Paulo: Fotoleser Gráfica e Editora, 2006.

GOMES, C.; BARBOSA, A. J. G. A inclusão escolar do portador de paralisia cerebral: atitudes de professores do ensino fundamental. Rev. Bras. Ed. Esp., v.12, n.1, p. 85-100, 2006.

LACERDA, C. B. F; SANTOS, L.F. Tenho um aluno surdo. E agora?: Introdução à Libras e educação de surdos. São Carlos: EdUFScar, 2013.

MANTOAN, Maria Teresa Égler; PRIETO, Rosangela Gavioli. Inclusão Escolar: pontos e contrapontos. São Paulo: Summus, 2006.

MATO GROSSO. Educação Básica do Mato Grosso. Cuiabá: Estado do Mato Grosso, 2002.

MENDES, E.G. A educação inclusiva e a universidade Brasileira. Revista Espaço. Rio de Janeiro, v. 18/ 19, p. 42-44, 2002/2003.

ORGANIZAÇÃO DAS NAÇÕES UNIDAS (ONU). Declaração dos Direitos Humanos. Genebra: Unicef, 1948. Disponível em: https://www.unicef.org/brazil/declaracao-universal-dos-direitos-humanos. Acesso em: 20 m1r. 2021.

PEIXOTO, Maria Angélica. Inclusão ou Exclusão: o dilema da educação especial. Goiânia: Germinal, 2002.

PRÁTICAS PEDAGÓGICAS para educação de alunos com deficiência auditiva. 06 dez. 2011. Disponível em: https://edspec.wordpress.com/2011/12/06/praticas-pedagogicas-para-educacao-de-alunos-com-deficiencia-auditiva/ Acesso em: 30 jul. 2021.

QUADROS, Ronice Muller de; KARNOPP, Lodenir Becker. Língua de Sinais Brasileira: estudos linguísticos. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2004.

RECHIGO, C. F.; MAROSTEGA, V. L. (Re) pensando o papel do educador especial no contexto da inclusão de alunos surdos. Revista Educação Especial, n. 19, p. 1-4, 2002.

SAMPAIO, S.; FREITAS, I. B de (Orgs.). Transtornos e dificuldades de aprendizagem: entendendo melhor os alunos com necessidades educativas especiais. Rio de Janeiro: Wak, 2011.

SKLIAR, Carlos; A Surdez, um olhar sobre as diferenças. 3. ed. Porto Alegre: Mediação, 2005.

STROBEL, K. L. Projeto de mestrado surdos: vestígios culturais não registrados na história. Florianópolis: UFSC, 2006.

APPENDIX – FOOTNOTE

6. Guidelines and Bases of Education.

[1] Doctoral Student in Teaching Exact Sciences-UNIVATES, Libras Interpreter, Teaching; Inclusion and Deafness.

[2] Pedagogue at FCSGN, Postgraduate in Psychopedagogy at FCSGN, Translator Interpreter of Libras, Education for the Deaf.

[3] Doctor in Electrical Engineering – UNEMAT.

[4] Master’s student in Teaching Exact Sciences – UNIVATES.

[5] Master in Teaching Exact Sciences.

Sent: June, 2021.

Approved: September, 2021.