OLIVEIRA, Rosane Machado de [1]

OLIVEIRA, Rosane Machado de. School Curriculum: A Body of Knowledge for Achieving Educational Goals. Multidisciplinary Scientific Journal. Edition 8. Year 02, Vol. 05. pp. 52-73, November 2017. ISSN:2448-095

ABSTRACT

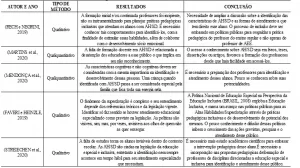

The present study deals with the study in relation to the school curriculum, as well as, it seeks to reflect the curriculum in the set of educational knowledge, and the curricular influence in the accomplishment of objectives in the school scope. Sometimes, a school curriculum that is collectively, democratically, "stuffed" with values, respect for diversity, and concrete, structured and meaningful teaching-learning in the formal environment is sometimes seen. The general objective of the research is to develop an analysis, a reflection about the socializing function of the school curriculum, where the school has been fragmented, that is, it does not value it as a historical-cultural, social and educational construction. The specific objective is to understand the importance and comprehensiveness of the school curriculum in the meaningful learning of students, both in the formal context and in the informal context. The methodological procedure is of a qualitative nature developed through exploratory bibliographic research. Through the result of the subject investigated, it was possible to understand that the school curriculum is a significant axis in the achievement of goals established in the school, which must be rethought, analyzed, elaborated and planned collectively, in the search of the school to obtain a constructive teaching-learning , as close as possible to the life and social reality of learners who come to school. The challenge analyzed contemporaneously is the lack of collective and critical awareness in the elaboration of the curricular proposal of the school, where it is verified that many agents of the educational process sometimes do not even present themselves in the curricular planning, as it is analyzed, that some schools have plenty of time for commemorative / festive activities (from February to December).

Keywords: Curricular Analysis, Activities, School Festivities, Fragmented Planning, Isolated Disciplines.

1. INTRODUCTION

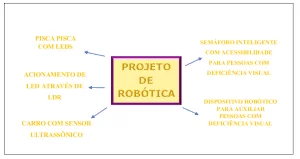

The purpose of this study is to analyze the importance of the school curriculum in the educational, social and cultural environment. The curriculum is a beneficial set of knowledge / knowledge, which should be analyzed ethically in the school context. achievement of objectives in the teaching-learning of students. It is necessary for the school, together with teachers / educators, parents and the school community in general, to be able to reflect, analyze, understand and verify that the school curriculum is an extremely important element in school and in the activities developed by the teacher / educator. Certainly, it is the school curriculum that allows a better organization of the contents and activities to be worked by the teacher in an ethical and democratic way. Since then, there must be the understanding on the part of those who make up the school team, that the curriculum goes beyond the comprehension of isolated disciplines, content, passive and fragmented knowledge. It can not be denied that fragmented knowledge is embedded in many schools of today, where undemocratic schools often seek to offer this manipulative knowledge to their students.

It is observed that when curriculum teaching is valued by the school staff, the curriculum certainly offers significant points in the expansion and achievement of constructive knowledge, contributing to a critical, active, reflexive and structured learning in the various social contexts.

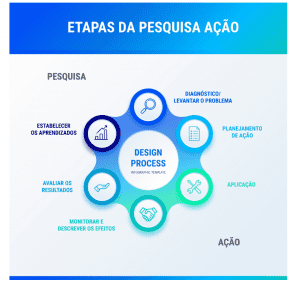

The proposed theme resulted from study, research, interest, analysis and critical reflection on the subject addressed (school curriculum), as well as active research, and understanding of the ideas of scholars who deepened the studies on the subject, in the search to verify which solutions and knowledge can be obtained to develop a more solid and comprehensive awareness about the importance of the school curriculum in the educational context and in the qualitative learning of the students. The study analyzed the importance and the comprehensiveness of the school curriculum in the social, cultural and educational life of students in the teaching-learning process, as well as in the construction of solid, critical, reflexive, and fluent knowledge for the live well, and interpret society. The methodological approach is qualitative, being developed through exploratory bibliographical research (books, scientific methodology, magazines, newspapers, notebooks, newspapers, etc.). In relation to the exploratory research, Gil (2010, p.27), describes that, exploratory research aims to provide greater familiarity with the problem, with a view to make it more explicit or to construct hypotheses.

Based on the studies about the curriculum in the school context and its social function, the following research problem was elaborated.

Why do many schools simultaneously use the school curriculum only for the appropriation of individual content and subjects?

In relation to this problem, the political, social, cultural, pedagogical and educational disintegration of those involved in the teaching-learning process is analyzed in some schools. There is a lack of commitment on the part of the school towards the school / student community community and society, since in fact many schools consider the school curriculum to be a mere grade of disciplines and nothing more. Unfortunately, when the curriculum is viewed in this way, surely the teaching-learning of learners becomes fragmented and disconnected from their social, cultural, ethnic, political and religious realities.

However, this fact does not address the cultural diversity present in our society, where the school curriculum is historical and can not be seen as isolated disciplines, but rather refers to a series of values that must be analyzed correctly by each education professional . The educational practice can not distance itself from the school reality and the life of the students that the school receives, because, in order to have a concrete social inclusion, the curriculum must be thought to attend and embrace cultural / social diversity, in the search to value the physical, social, affective, cognitive and emotional aspects of each student. Therefore, the school curriculum is a set of elements / knowledge that provides very precise and qualitative knowledge. The study aims to contribute positively to teachers, educators, tutors, directors, school staff, so that they can reflect on the practice and curricular theory established in schools and the social, cultural, affective and human formation of all students.

2. SCHOOL CURRICULUM: A KNOWLEDGE OF KNOWLEDGE IS TO BE ANALYZED IN THE EDUCATIONAL CONTEXT

The word curriculum derives from the Latin curriculum (derived from the Latin verb currere, which means to run) and refers to the course, route, path of life or activities of a person or group of people (GORDON apud FERRAÇO, 2005, p. 54). Already, according to the Aurelio Dictionary of the Portuguese language, Ferreira (1986, p 512), curriculum is defined as "the part of a literary course, the subjects included in a course". According to Zotti (2008), the term was used for the first time to characterize a structured study plan, in 1963, in the Oxford English Dictionary.

It is important to rethink the socializing function that the school curriculum must exert in the educational field. At the same time, it is analyzed that the school curriculum can not be seen or understood, such as an "accumulation" of isolated, fragmented disciplines with content presented in a traditional way, and transmitted without reflection by the teacher / educator in the classroom. It is verified that the school curriculum is historical and goes beyond contents and disciplines, and the curriculum must be elaborated in such a way as to provide conditions of knowledge for the students, in the search of covering and attending to the diverse social realities, in a broad, real, meaningful, reflective, dynamic, democratic, inclusive, ethical and moral way.

To discuss the school curriculum in contemporary times is to analyze the educational system deeply, as well as what the human being produced and continues to produce over time, called history. Therefore, it is necessary to seek to understand the knowledge elaborated and appropriated by all members of society, as well as the various cultures existing, gradually enlarged or even modified from generation to generation.

The curriculum is transformation, not only in terms of changing the meaning, of going the other way, but of seeking new alternatives, new solutions, new goals and new achievements. The curriculum consists of transforming the inaccurate into known, and this fact, involves a qualitative teaching-learning.

Curriculum is never simply a neutral assemblage of knowledge, which somehow appears in the books and classrooms of a country. Always part of a selective tradition, of the selection made by someone, the visions that some group has of what is the legitimate knowledge. It is produced by the cultural, political, and economic conflicts, tensions, and commitments that organize and disorganize a people. (APLLE, 2000, p.53)

The curriculum represents the path that the subject will make throughout his / her school life, both in relation to the appropriate contents and the activities carried out under the systematization of the school. In this sense, Sácristán and Gómez (1998, p. 125) affirm that "schooling is a course for students, and the curriculum is its filling, its content, the guide of its progress through schooling."

In the school context, the curriculum must have a formative, educational, social and cultural function. The school curriculum, as a practice of transforming reality and concrete knowledge, needs to be constantly debated and reflected by all those who make up the school staff, where all school professionals must be prepared to understand that curriculum is essential in pedagogical praxis and in the school, social and cultural life of all students who come to school in search of meaningful knowledge. According to Krug (2001, p 56).

The curriculum arises, then, in a broad dimension that understands it in its socializing and cultural function, as well as the form of appropriation of accumulated social experience and worked from the formal knowledge that the school chooses, organizes and proposes as school activities center.

Currently, there are still teachers / educators, who demonstrate understanding of the school curriculum, as a purely technical, passive / neutral area. According to Moreira and Silva (1994, p.7), the curriculum has to have a critical "tradition" because:

The curriculum has long since ceased to be merely a technical area, focused on questions relating to procedures, techniques, methods. One can now speak of a critical tradition of curriculum, guided by sociological, political and epistemological questions. Although curriculum issues remain important, they only make sense within a perspective that considers them in their relation to questions that ask why the forms of organization of school knowledge.

It is interesting to recall that the definitions of curriculum up to the nineteenth century referred strictly to matter, as Zotti (2008) indicates:

Inserted in the pedagogical field, the term passed through diverse definitions throughout the history of the education. Traditionally the curriculum meant a relation of subjects / disciplines with their body of knowledge organized in a logical sequence, with the respective time of each one (grid or curricular matrix). This connotation is closely related to the "study plan", which is treated as the set of subjects to be taught in each course or series and the time reserved for each one.

After the nineteenth century, the meaning of curriculum will take another proportion, which includes not only school knowledge but also, learning experiences. Thus, the curriculum involves both the construction and the improvement necessary for the development of the subject. According to Moreira and Candau (2008, p.18).

Curriculum is thus associated with the set of pedagogical efforts developed with educational intentions. For this reason, the word has been used for any and all organized space to affect and educate people, which explains the use of expressions such as media curriculum, prison curriculum, etc. We, however, are using the word curriculum only to refer to activities organized by school institutions. That is, to refer to school.

We can understand that when we talk about curriculum, we are dealing with the school, that is, how the contents are dosed and sequenced in the pedagogical process. There is no single curriculum to be followed by all Brazilian institutions, since in its art. 26 Law No. 9,394 / 1996 (National Education and Guidelines Law) defines common National Base subjects, those that must be taught throughout the country, and a diversified part, the one required by regional and local characteristics society, culture, economy and clientele. In this way, the Common National Base is the minimum set of content articulated to aspects of citizenship. Because it is mandatory in national curricula, the Common National Base should predominate in relation to the diversified part.

According to the opinion CNE / CEB 4/98, which establishes curricular guidelines for Elementary Education, the diversified part "involves the complementary contents, chosen by each school system and schools, integrated to the Common National Base, according to the regional and local characteristics of society, culture and economy, reflecting, therefore, the Pedagogical Proposal of each school, according to article 26. (BRAZIL, 1992)

In addition, it constitutes a broad range of curricula in which the school can exercise all its creativity, in order to meet the real needs of its students, considering the cultural and economic characteristics of the community that acts, essentially building it through the development of projects and activities of interest. The diversified part can either be used to deepen elements of the Common National Base, or to introduce new elements, always according to the needs. In High School, it is a space in which professional training can be initiated, by offering curricular components that can be used in the technical area of the corresponding area.

If it is important for the school to be able to count on a portion of the curriculum freely established, for the student this can be an important opportunity to participate actively in the selection of a syllabus. This can happen in the choice of elective or optional disciplines, for example. "The optional subjects are those that, being compulsory, admit that the student chooses among the available alternatives, but can not fail to do them[…]. Optional subjects are those that the student adds to a syllabus that already meets the minimum required by the school "(BRASIL, 2006). That is, elective courses are part of the compulsory curriculum, while facultative disciplines can be chosen freely to complement the curriculum.

However, the law indicates that it is the responsibility of the school to draw up its pedagogical proposal. In continuation, the National Education Guidelines and Bases Law (LDBEN) identifies the general outlines for the organization of pedagogical work in schools. In art. 27 of the law that deals with basic education, we can highlight the following guidelines regarding the contents of school curricula of basic education.

Art. 27. The curricular contents of basic education will also observe the following Guidelines:

I – the dissemination of fundamental values to the social interest, the rights and duties of citizens, respect for the common good and the democratic order:

II – consideration of the educational conditions of the students in each establishment:

III – work orientation;

IV – promotion of educational sport and support for non-formal sports.

The school curriculum is an enriching element of the teacher / educator's work in the formal context and in the non-formal context. The curriculum is of paramount importance for the life and planning of the teacher, since it is the curriculum that allows the teacher a fixed organization of contents and activities in a clear, critical, autonomous, reflexive, active and democratic way in the school context, being the curriculum, a resource for teaching and learning and the significant development of students in society.

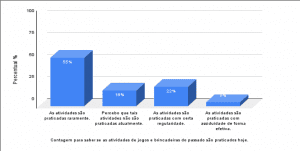

It is necessary to reflect, on the several activities elaborated in some schools, where, one observes the extensive workload used for the accomplishment of festive / commemorative activities in the educational scope. It is known that there are many commemorative dates that the schools acquire as a "popular tradition", dates that begin to be celebrated at the beginning of the year in the month of February, when the students return to the classes, being that such celebrations only end in December, and thus ends the year, with a "filling of festivities, without reflection for the human life of students." It should be emphasized that not everything that happens or takes place in school can be considered in the school curriculum, due to the fact that there is no intentional reflection on the activities elaborated within the educational context.

Saviani (2000), in dealing with content that is worked in school, states that teachers often spend a lot of time on secondary issues to the detriment of the real need of the school. One loses a lot of time with decontextualized activities, such as the various celebrations held during the school year, from carnival to Christmas. These activities, in their majority, start from isolated actions, not linked to the planning, and with an ideological conception that relegate to the background the historical questions that pervade those festivities.

According to the same author, the school could devote its time to the appropriation of scientific knowledge. In the words of Saviani (2000: 1):

I give just one example: the school year begins in February and soon we have the Indian week, Easter week, mothers' week, folklore week, the June festivities, in August comes the week of the soldier, then the week of the homeland, tree week, spring games, child's week, teacher's party, public servant, wing week, republic week, flag party, and at that point we have reached the end of November. The school year ends and we are faced with the following observation: everything was done in school; time was found for every kind of celebration, but very little time was devoted to the process of transmission-assimilation of systematized knowledge. But, one may ask: what is the problem? If everything is curriculum, if everything the school does is important, if everything competes for the growth and learning of the students, then everything it does is valid and the school has not failed to fulfill its educational function. However, what happens is that, from week to week, celebrating in celebration of the truth, the school has lost sight of its nuclear activity, which is to provide students with the acquisition of instruments to access elaborate knowledge.

It is imperative to rethink the critical idea of the author Saviani (2000), an idea that allows us to analyze, in fact, that the school has, for a long time, commemorative, fragile and secondary activities. It is important to add, that no one is claiming that these activities are unnecessary in the school context, quite the contrary, commemorative activities, historical and cultural, must be realized, experienced, practiced and truly understood by students in the school environment, where such activities must to be practiced in a more real and reflective way, and not only for the teacher to arrive in the classroom and say to the students, for example: "Today we celebrate the day of the Indian, we will color in sheet of sulphite paper, the village, which represents the community of indigenous peoples ". Note that only the students know that such a date is celebrated Indian day, and that the village represents the community of indigenous peoples, will not contribute to the learning of the students, much less to expand any knowledge or understanding, because , the subject needs to be exemplified, the story needs to be told with values, teachings, principles and especially with reflection and critical analysis.

There is no denying that there is a distancing of the school activities with the social reality of the students, the school and the teachers / educators, they need to propose more concrete teaching methodologies, as well as being more open to dialogue, in search of a conversation sensitized with the parents and with the students that arrive to the school, in the attempt to know concretely the reality of the students, for then, to be able to offer a learning of quality, being that this learning must attend the needs and the diverse realities of the students in process of schooling.

However, it should be noted that such commemorative activities must have certain limits, as there are many celebrations from February to December at school. There is no way to counter the opinion of the author Saviani (2000), when he says that the school wastes a lot of time with commemorative and secondary activities. If we stop to reflect, and analyze concretely every festive day that the school celebrates, and can not "hang up", not even leave aside any celebration, surely, we will understand the time load wasted with repetitive activities every year in the school context , year after year, commemorative activities follow the same pattern, that is, February celebration in December. Faced with this fact, it is also possible to understand the many learning difficulties that so many students face during the whole year in school, because with so many celebrations and festivities, the time for reflection and the concrete assimilation of knowledge, is limited.

Example: june party celebrations seem to be simple, routine, with little rehearsal time, but if we go to any school, we accompany the class, the teacher / educator in the rehearsals, in the dances, in the students' understanding of how to dance and to understand the music presented by the educator, in that time, one can observe how many hours and how many lessons one ends only of explanations that is necessary for the accomplishment of the dance and for the understanding of the music. In the June festivities, it is interesting to remember that the test per class can take up to a month, obviously it is not rehearsed every day at school, but of course, it is rehearsed at least twice a week.

Obviously, this curricular culture installed inside the schools, gradually damages the scientific development of the students, which needs to be modified from time to time. It is almost "normal" to see or read in newspapers, books or magazines, how much is constant in some schools, students do not learn the basics of human and educational values, so that they can live well in society. Unfortunately, teaching-learning is very fragile, passive, fragmented, and does need a restructuring in the school learning of all students. The timetable for commemorative activities in the school context must be taken into account, that is, it needs to be reduced, because if we reflect a little on so many celebrations all year, we will conclude that the school does not have to celebrate every festive date, as highlighted in the calendar traditionally.

In the structuring of the curriculum it is important the appropriate administration of the time: of the school, regarding the fulfillment of the academic year, of the student, optimizing the use of its permanence in the school environment; and the teacher, for the correct use of the workload of their work contract. In addition, it is necessary to distribute, throughout the different academic years – whatever the organization adopted in the school, in semester, annual, cycle, stage or module series – the programmatic content, the planned complexity of activities and the increasing autonomy of students in the development of tasks, acquisition of skills and demonstration of competences (BRASIL, 2006).

The school, when it follows the traditional calendar step by step, and a curriculum based on contents and isolated disciplines, causes the impression that such a school does not care about or if it reflects on the learning and the difficulties found in the teaching of the students, as well as in the scientific, social, cultural, and active development of students in society. In addition to commemorative activities, students first need concrete, qualitative, democratic, autonomous and inclusive teaching and learning in different social contexts.

The school curriculum, when well developed by the school community, seeks to attend to the cultural diversity present in the school, and at the same time, it offers a significant set of knowledge, which must be understood in a democratic way in the school context, since when the curriculum presents passive content , it is certainly because the school is also passive in front of the learning process. The school must strive tirelessly for the formation of human, scientific consciousness, and not only perform the task of preparing students for the needs of the labor market, because in this emphasis of work, the school is not able to train its students for citizenship, nor does it allow the students to understand and understand their rights and duties as human beings.

On this issue, Wihby, Favaro and Lima (2007: 13) propose:

The struggle for the guarantee of a public school of the best quality possible in the current historical conditions, that surpasses the capitalist pedagogical projects, the paradigm of the market applied to education, going beyond the function of preparing for the job market or university. The objective should be to assure individuals the appropriation of systematized knowledge, that is, of science, propitiating the development of a more elaborate conception of the world, that makes possible their comprehension, the apprehension of its multiple and complex dimensions, for a human performance more rational and conscious.

In this sense, it is analyzed that school curriculum should be better elaborated in the school, because the curriculum is a set of knowledge in favor of the teaching-learning of the students, and when it is well planned, organized and elaborated collectively by all in the context knowledge will be much more comprehensive, qualitative and rewarding for all who are part of the learning-learn process. What is often analyzed are school institutions that do not know how to make good use of the school curriculum, where they end up devaluing it, or fragmenting it. However, the passive school that does not value the curriculum as fundamental in the pedagogical praxis, obviously can not train critical citizens, does not humanize, does not sensitize towards respect for differences, nor does it activate the critical / reflective thinking of students, just as it does not interests of the community, let alone the students in the process of learning and knowledge.

Faced with this fact, it can be said that when there is a teaching-learning in the school without strategy, without structure and without reflection for human development, surely such teaching must be totally excluded from the school and the life of all who make up the space formal.

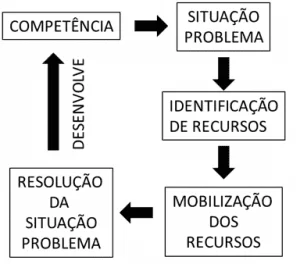

2.1 THE SCHOOL CURRICULUM AS AN AXIS IN THE CONCRETIZATION OF EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

The school curriculum is very significant in the educational practice, in the day-to-day in the educational scope, being the curriculum, an axis for the attainment / accomplishment of the objectives proposed by the school. The school curriculum is part of the history of Brazilian education, so the curriculum is historical, which has undergone debates, transformations, changes, and changes innumerable times in the educational context.

At the same time, the school curriculum plays an important role in the formal environment, since the curriculum is an indispensable and essential tool for knowledge and social, cultural, educational and educational transformation of children, young people and adults. The curriculum must have a basis and a collective, inclusive and never neutral structure. At the same time, the curriculum should provide the student with access to the set of historically produced knowledge, both for the student's school life and for the social life of the student. The curriculum has to be looked at by educators in a differentiated way, much more than a simple curriculum to be fulfilled, but an ethical commitment in teaching-learning, in the search to investigate and reflect on theoretical and practical questions that guide pedagogical practice aimed at meeting the demands of today, and especially the cultural diversity present in educational institutions.

The school curriculum has always been a fundamental element for the decisions and reflections of the pedagogical practice in the school context. It is essential to report a little of the history of education, where it is analyzed that the first model of Brazilian education was characterized by the Jesuits, who arrived in Brazil in 1549 and brought with them a well-defined education program called Ratio Studiorum . Jesuit education was based on a fragmented, decontextualised, and ideological teaching based on the traditional method, and this method of traditional teaching valued memorization, approval, quantitative income and student decree, where only the teacher / educator "was the owner of knowledge", that is, the person who possessed any and all teaching / knowledge, the teacher being the transmitter of fragmented knowledge, without any reflection on the life of the students. The Jesuit period lasted 210 years in Brazil, at that time the period was marked as Jesuit education, where disciplines and school contents were already organized so as to keep a certain distance from reality. It is essential to remember that the term curriculum was not mentioned in the teaching of the Jesuits, since the term appeared only in 1963, that is, at Jesuit time in 1549, they obtained a traditional and moral education based on a range of disciplines established by the Jesuits themselves, disciplines that, at the same time, we mean by school curriculum.

It is common for us to hear, people of age speak, that in the last century or in "the most severe times", everything was more difficult for people, we can then think about the past, and reflect sharply, for example: what was the opportunity of study of so many people decades ago? Or, what was people's life like in the past was more beneficial or more rigorous than ours today?

Certainly, we will know the answers, if once questioned, then our great-grandfathers, grandfathers or any other person of age, have added facts, or told some stories about the time lived by them and their family.

To summarize this reflection, so many people did not study decades ago because of lack of concrete opportunities in the education system, the difficulty of transportation that did not exist, the extreme poverty lived by such people, and today many are not dedicated and do not study for lack of interest and not opportunity, this is a real and sad situation that we face in contemporary society.

It is essential to remember that at the end of the First Republic 80% of the Brazilian population was illiterate. As mentioned above, these eighty per cent can be concluded, that they were persons of the working class, of the proletariat, who had no access to education, much less opportunity to carry out their studies. Since then, with the majority of the population not knowing how to read, write and calculate, the Vargas government's amazement and concern was broad, as the government wanted the country's prosperity / growth, and with an illiterate people Getúlio Vargas would never achieve the long-awaited prosperity for Brazil. Therefore, in 1930, the government of then President Getúlio Vargas considered education as fundamental for the qualification of work and for the formation of the human person, offering free public education for all. However, it is observed that school education began to develop with more priority, during the government of Getúlio Vargas, where the process of urbanization and industrialization took place in Brazil, with work and education becoming necessary for growth the country.

It can be seen, then, that the school curriculum has very precise political purposes. Zotti (2004) states that official curricula have been developed throughout history to meet economic demands. In this sense, all the changes in the curricular field that were already carried out followed the political interests of the current economic model. The author leads us to reflect on the political-economic implications that subsidized the construction of official curricula throughout the history of Brazilian education. This way of thinking the curriculum gives rise to questions about what has already been established in the curricular field, the possible hidden ideologies and the eminent contradictions, when the pedagogic discourse is compared with the school reality.

In this approach, the school, together with the teachers / educators and the school community in general, should analyze the achievement of the curriculum in the pursuit of specific educational goals, with the intention of offering new possibilities to the students, while at the same time creating opportunities for all through learning, and teaching must be committed to the interests of the whole society, especially with the interests, and the diverse realities of the students. The teacher educator has a fundamental role in the elaboration of the curriculum in the school, being that the same one must always be involved in the school subjects. For Moreira and Candau (2007).

The curriculum is, in other words, the heart of the school, the central space in which we all act which makes us, at different levels of the educational process, responsible for its elaboration. The role of the educator in the curricular process is thus fundamental. He is one of the great architects, whether or not, of building the constructed curricula that systematize in schools and classrooms. (MOREIRA and CANDAU, 2007, p.19).

The school curriculum at the same time is very fragmented, with no relation to the lives of the students who come to school. It is analyzed in many schools that the curriculum is not rethought and used to materialize the teaching-learning of students in a diversified, active, democratic, critical and social way.

Obviously, many schools insist on using the traditional teaching method in the school context. It is observed that schools, when they seek to prioritize and offer a fragmented and traditional teaching to their students, are certainly schools that focus on the passive contents and disciplines to be followed without active reflection, and yet they are totally distant from social reality of learners attending school, as well as the population in general.

In relation thereto Mantoan states:

The curricular teaching of our schools, organized in disciplines, isolates, separates knowledge rather than recognizing their interrelations. Contrarily, knowledge evolves by recomposition, contextualization and integration of knowledge in a network of understanding. Knowledge does not reduce complex to simple, to increase the ability to recognize the multidimensional nature of problems and their solutions. (MANTOAN 2006, p.15).

Schools, together with their educators, need to organize and verify differently the school curriculum, focusing on social reality, not just encyclopedic content. The contents should be worked in accordance with the different realities found in each school, in each classroom, because the school must train citizens of critical awareness, for human and scientific knowledge. The students need to be able to question the different realities, as well as to understand the often "masked" injustices in our society, if curricular teaching is passive, we will not be able to develop critical awareness in teaching-learning, and therefore we will not listen cultural diversity.

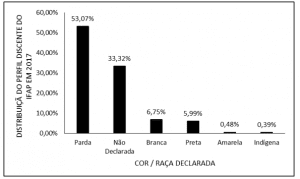

It is known that curricular construction is a project that must take into account many contemporary factors, such as (social class, economic, religion, family, race, gender, values, learning difficulties, even the emotional ones of learners ), Zotti (2004: 229) argues that:

The educator, then, can not limit himself to developing what several agents decide, but he must be attentive to the different contexts in which the curricular proposals are generated, since this is the instrument of intervention and defense of proposals coherent with an education and a society more in keeping with the wishes of the majority of the population.

The school must have a socializing function, and the curricular project has to be elaborated based on practical and educative actions, collective actions, interactivity, and intentionality in teaching-learning, understanding the historical facts of the past, as well as the cultural diversity present in the various social contexts. Regarding the curricular project, Pacheco (2001) states:

[…] a project whose construction and development process is interactive, which implies unity, continuity and interdependence between what is decided at the normative or official level and at the level of the real plan or the teaching and learning process. Moreover, curriculum is a pedagogical practice that results from the interaction and confluence of various structures (political, administrative, economic, cultural, social, school …) on the basis of which concrete interests and shared responsibilities exist. (PACHECO, 2001, p.20)

Understanding the differences and contemplating the multiplicity of individuals that make up the same classroom is in fact knowing how to include with values and principles as mandated by existing educational legislation. The curriculum should be used to enable social transformation and not to be kept in a drawer and from time to time be looked at, and checked the discipline grid in the curriculum contains.

Since then, as verified in the development of the work, the school curriculum must be seen as, "the heart of the school", that is, the curriculum has to be respected, collectively and democratically valued in the educational and social spheres, since it is the curriculum that social, cultural and educational actions in educational institutions.

3. METHODOLOGY

In order to understand the importance of the school curriculum in the accomplishment of specific educational objectives, the accomplishment and conclusion from the article was based on an exploratory bibliographical research carried out in libraries and public schools in the municipality of Bela Vista da Caroba – PR and Royalty – PR. Where it was used (books of scientific methodology, literary and didactic works, scientific articles, dictionaries, magazines, newspapers, etc.).

The research identified the need of the school together with the teachers / educators, to review pedagogical practices, as well as, to understand clearly the influence and importance of the school curriculum in the diverse social contexts. It is imperative that the school understands the significant role that the curriculum plays in the school space, because the curriculum function is broad, and it is not only about contents, but about experiences, values, attitudes, social, economic, cultural, and a qualitative learning, based on the diverse realities of each student that arrives at school. The bibliographical research as mentioned above was carried out based on bibliographical material related to the subject addressed, analyzed in writings merely pedagogical under the view of several authors, as well as in their works.

According to Silva and Menezes (2005, p.20), the qualitative research "considers that there is a dynamic relationship between the real world and the subject, that is, an inseparable link between the objective world and the subjectivity of the subject that can not be translated into numbers. "

The study of a qualitative nature allowed a significant and constructive deepening on the school curriculum and the set of activities developed by the school in the different social contexts.

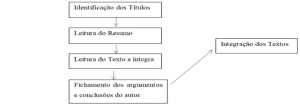

The research was developed through concrete actions and investigations, as well as reading, precise knowledge, reflection, and based on a critical analysis on the guiding theme of the work.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

During the development of the scientific article, it was analyzed, that the school curriculum is much more than a simple grid of disciplines to be worked / studied or shelved in the school environment. The curriculum is a tool that allows clarity and lucidity in the organization of knowledge, methods, resources, adaptations, among others. Therefore, the school curriculum involves environmental, political, economic, social, cultural and educational issues, for this reason, the curriculum can not be used by the school as a model of reproduction of knowledge, nor even as a discourse of alienation on the issues school children.

It is necessary to have an understanding on the part of all school staff that the curriculum should not be organized in isolated subjects, since this form of organization separates, fragments and impoverishes the interrelationships between teachers, students and the school community, as well as as it impoverishes teaching and learning.

Schools, along with teachers / educators, need to review pedagogical practices and revert some traditional models of teaching and content based on methods of memorization, memorabilia, alienation and unrelated to the lives of students. The need to adapt the school curriculum to the social-historical reality of the students who reach the school, in the search of appreciating the cultural and social differences of such students, is perceived. The curricular adaptation is essential, and it favors the understanding of differences in the educational scope, where it is analyzed, that schools when they seek to acquire such curricular adaptations, in fact, are schools able to contemplate and respect the multiplicity of subjects that make up or not the classroom, in a democratic, inclusive, ethical and moral way.

It is observed that the school curriculum is an indispensable instrument in the organization of the pedagogical (formative) work. It is also noted that there is no exact understanding of the school curriculum, because when we talk about curriculum in any educational environment, or for example in a meeting, many people have in mind, which curriculum means the grade of subjects which should be studied, that is, the contents to be passed on to the students in the classroom, but if we analyze the true curricular function better, we will see that it is not quite so, there is a misunderstanding in this thought that (the curriculum is school curricula), because the curriculum is the foundation of the school, and not only contents are taught, transmitted and memorized. However, the school as a social function should provide a necessary basis for understanding, for reflection, for the appropriation of the curriculum in a sensitized and adequate way.

The results of the research were merely qualitative / meaningful, where it was possible to verify that the school curriculum is "the heart of the school", that is, if the curriculum is well planned and elaborated collectively with the participation of the school community, develop a critical, reflexive, autonomous, and intentional learning based on precise and epistemological pedagogical knowledge. Therefore, it is fundamental that all the agents involved in the elaboration of the curriculum, get some care at the time of preparation, because, to elaborate a curriculum, it is not only to select passive, centralized, ready and finished contents to be worked in the classroom.

However, I may add that the subject covered needs new scientific studies, because there is no denying that the curricula in some public schools seek to serve the interests of the ruling class, and that such interests are ideological, and in fact cause exclusion social situation of thousands of school children, because when the school seeks to meet the interests of a dominated class, such as the bourgeoisie, certainly this same school, does not meet the wide diversity that exists in formal space, and the school at that moment starts to reverse their role, that is to say, instead of the school include the students that would be their obligation as educator, the school happens to exclude the majority of the students, certainly the educandos children of the class of the proletariat.

It is verified that there are few studies about the theme presented, as well as little analysis, reflection / awareness about the importance of curriculum in the educational, social, economic, cultural, among others, for this reason, new research in the area is recommended.

References

APLLE, Michael W. Rethinking ideology and curriculum. In: MOREIRA, A.F .; SILVA, T.T. Curriculum, Culture and Society. 4. ed. São Paulo: Cortez, 2000.

BRAZIL. Law No. 9,394 of November 20, 1996. Official Journal of the Union, Legislative Branch, Brasília, DF, December 20, 1996. Available at: www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/LEIS/L9394. Accessed on: April 22, 2010.

___________. Ministry of Education and Culture. Available at: www.mec.gov.br Accessed on: 16 Aug. 2006.

Chamber of Basic Education. Opinion CEB No. 04/98: National Curricular Guidelines for Elementary Education. Brasília: MEC / CNE, 1998b.

FERRAÇO, Carlos Eduardo (Org.). School Daily, Teacher Training and Curriculum. São Paulo: Cortez, 2005.

FERREIRA, A. B. de H. New dictionary of the Portuguese language. Rio de Janeiro: New Frontier, 1986.

GIL, Antonio Carlos. How to design research projects. 5. ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 2010. 184p.

KRUG, A. Training Cycles: a transformative proposal. Porto Alegre: Mediation, 2001.

LIMA, Michelle Fernandes. The role of the curriculum in the school context / Michelle Fernandes Lima, Claudia Maria Petchak Zanlorenzi, Luciana Ribeiro Pinheiro. – Curitiba: InterSaberes, 2012. – (Teacher Training Series). Bibliography. ISBN 978-85-8212-110-8

MAIA, Christiane Martinatti. Didactics: organization of pedagogical work / Christiane Martinatti Maia, Maria Fani Scheibel. – 1.ed., rev. – Curitiba, PR: IESDE BRASIL S / A, 2016. 192 p .: il .; 28 cm. ISBN 978-85-387-6219-5

MANTOAN, M. T. E. School Inclusion: What is it? For what? How to make? 2. ed. São Paulo: Modern, 2006

MOREIRA, Antônio Flávio Barbosa. Text – Inquiries about curriculum: curriculum, knowledge and culture / Antônio Flávio Barbosa Moreira, Vera Maria Candau; organization of the document Jeanete Beauchamp, Sandra Denise Pagel, Aricélia Ribeiro do Nascimento. – Brasília: Ministry of Education, Secretariat of Basic Education, 2007.

MORREIRA, A.F. CANDAU, V. M. Multiculturalism: cultural differences and pedagogical practices. São Paulo: Vozes, 2008.

MORREIRA, A.F. SILVA, T. T. da (Org.). Curriculum, culture and society. São Paulo: Cortez, 1994.

PACHECO, José Augusto. Curriculum: theory and praxis. Oporto: Porto Editora, 2001.

SACRISTÁN, J. G; GOMES, P. Understanding and transforming the school. 4. ed. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 1998.

SAVIANI, D. The musical education in the context of the relationship between the curriculum and society. In: ANNUAL ENCOUNTER OF THE BRAZILIAN ASSOCIATION OF MUSICAL EDUCATION, 9, 2000, Belém. Anais …. Bethlehem: Abem, 2000. Available at: www.fae.unicamp.br/dermeval/texto2000-1.html. Accessed on: January 25, 2010.

SILVA, E. L. da; MENEZES, E. M. Methodology of the research and elaboration of dissertation. 4. ed. Florianópolis: UFSC, 2005. 138 p. Available at: www.portaldeconhecimentos.org.br/index.php/eng/content/view/full/10232. Accessed on: 10 Oct. 2009

WIHBY, A; FAVARO, N.A. L. G; LIMA, M. F. School and the limits and possibilities for the formation of human consciousness. In: CONGRESSO INTERNACIONAL DE PSICOLOGIA, 3; WEEK OF PSYCHOLOGY, 9. 2007, Maringá. Anais ….. Maringá, 2007. Available at: www.cipsi.uem.br/anais2007/trabalhos/getdoc.php?tid=109. Accessed on: February 19, 2010.

ZOTTI, S. A. Curriculum. In: UNIVERSITY OF CAMPINAS STADUAL. Education University. Navigating the history of Brazilian education. Available at: www.histedbr.fae.unicamp.br/navegando/glossario/verb_c_curriculo. Accessed on: 25 October 2008.

__________. Society, education and curriculum in Brazil: from the Jesuits to the 1980s. Campinas: Associated Authors; Brasília: Plano, 2004.

[1] (FACINTER), Specialization in Special and Inclusive Education (FACINTER), Specialization in Teaching in Higher Education (Faculty of Education São Luís), Postgraduate in Pedagogy by the Faculdade Internacional de Curitiba – PR, -Graduanda in School Management: Orientation and Supervision (Faculty of Education São Luís)