ORIGINAL ARTICLE

ARAÚJO, Gizelda Rodrigues de [1], MARQUES, Edmilson [2]

ARAÚJO, Gizelda Rodrigues de. MARQUES, Edmilson. Commodity fetishism in the planned obsolescence society. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 05, Ed. 11, Vol. 10, pp. 146-154. November 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/education/planned-obsolescence

ABSTRACT

This work approaches Marx’s commodity fetishism, bringing to light some examples that refer to use value and exchange value and reflects on the advent of programmed obsolescence, focusing on the volatility with which the fascination of merchandise disappears and punctuates that the pattern of consumption has become a form of social affirmation and consequently consumerism represents an important pillar for capitalism. Therefore, it aims to understand about the fetishism of merchandise in line with the programmed obsolescence of today’s society. This is an exploratory bibliographical research and, for that, it counted on the contribution of Marx’s studies in his book O Capital, specifically in the part that deals with the Commodity, Bauman. In the book Modernidade Líquida, where he discusses the fluidity of objects and the disposal of merchandise and Netto emphasizes work, society and value.

Keywords: Commodity fetishism, Planned obsolescence, Liquid modernity.

INTRODUCTION

We live in a so-called postmodern society, where consumerism reigns, making us alienated and at the same time indebted. A product that we acquire today will soon be considered démodé[3], due to the uncontrollable need to frequently change the merchandise that we just acquired.

From the Industrial Revolution, the capi

talist way of life extrapolated in such a way that society started to value having more than being. Being a consumerist was a way of establishing oneself socially. In this way, consumerism becomes essential for the maintenance of current capitalism.

This exacerbated consumerism exploded in 1928, when an influential US magazine published a phrase that changed the entire profile of society: “An article that does not wear out is a tragedy for business”[4].

From then on, goods that were durable, that were produced to last a lifetime, now in the name of capitalism, had a reduction in their useful life – they are disposable and, having a programmed lifetime, force the consumer to discard of this commodity in a shorter time.

It is understood with this, that it is a “trap[5]” of the capitalist system, which, realizing that a commodity that had a greater durability took much longer to be exchanged and with that stagnated the circulation of goods and consequently of the capital. It was a loss, because the dynamism was very slow. Once the useful life of the product decreases, the individual exchanges more frequently, thus increasing the dynamics of capital.

Zygmunt Bauman (2008), called this consumption relationship, planned obsolescence, that is, the intentional reduction of a product made by the producer or manufacturer, in order to force the consumer to discard the “old” model and buy a new model. Consuming has had a negative effect on personal relationships, in the sense that the desire to consume everything creates a distancing between people and even achieves it, since, when consuming too much, they often become indebted and conflicts at work begin to escalate arise, causing anguish and even depression.

METHODOLOGICAL PROCEDURES / METHODOLOGY

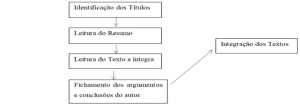

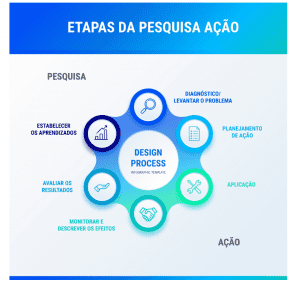

This is a bibliographical research, since it was from the survey of theoretical references, published by written and electronic means, such as books, scientific articles and web pages, that information or prior knowledge about the problem being sought was collected an answer.

According to Lakatos and Marconi (2003), this type of research is not a mere repetition of what has already been said or written about a certain subject, but provides an examination of a subject under a new focus or approach, reaching innovative conclusions.

As for the objective, it is an exploratory research, because according to Gil (2007), this type of research aims to provide greater familiarity with the problem, with a view to making it more explicit or building hypotheses.

DEVELOPMENT

The world has gone through several social revolutions and throughout history it can be seen that the mode of production has been diversifying as man has increased his needs. In the beginning, the production of goods depended solely on nature (hunting, fishing, fruits), but as man discovered new techniques for producing his food or clothing, a new society emerged. Man then begins to transform natural materials into products that meet his needs, through activities that we call work.

Netto (2006), stresses that activities that meet survival needs are generalized among animal species, exemplifying the case of Rufous Hornero and the bee in which both carry out their activities because they had already been programmed in a natural relationship and the environment environment.

However, between man and nature, this programming does not occur, since man has a way of working that belongs exclusively to him.

Uma aranha executa operações semelhantes à de um tecelão e a abelha envergonha mais de um arquiteto humano com a construção dos favos de sua colmeia. Mas o que distingue, de antemão, o pior arquiteto da melhor abelha, é que ele construiu o favo em sua cabeça, antes de construí-lo em cera.[…] ele não apenas efetua uma transformação da forma da matéria natural, realiza, ao mesmo tempo, na matéria natural, o seu objetivo.(MARX, 1983, apud NETTO, 2006 ,p. 31).

Possessing this planning capacity, man produces goods that are use values – the merchandise, which comes to satisfy his human needs (whether those we invent, which he does not have much need for or those we need to survive). However, it is worth mentioning that when this commodity is produced only for use and is not reproduced for exchange, that is, it is not intended to be sold, marketed or consumed, it does not constitute a commodity, it is just a use value.

For Marx (1983) all commodities have two characteristics: use value and exchange value. Since the use value is always related to the physical characteristics of the commodity. The exchange value is related to the proportion of which this commodity can be exchanged in a social relationship. The value of the exchange is always very fluctuating because it depends on the individual’s interest and cannot be defined by the characteristics.

In this way, it is understood that the commodity is:

A mercadoria é, antes de tudo, um objeto externo, uma coisa que, por meio de suas propriedades, satisfaz necessidades humanas de um tipo qualquer. A natureza dessas necessidades – se, por exemplo, elas provêm do estômago ou da imaginação – não altera em nada a questão. (MARX, 2005 p.157)

Marx (2005) also draws attention to the fact that this commodity is produced today in a totally fragmented way, where each individual does a part of the work to form the commodity.

The big problem generated by this type of production, still according to Marx (2005), is the fact that the worker does not recognize himself in the product he makes. And this occurs because now he is alien to his merchandise, since, before, the individual produced everything, from the base to the finishing of a merchandise (planned, created, defined the type of material, designed and finished the work). Everything was produced by one person.

In contemporary times, through flexible companies, each one makes a part of the merchandise to speed up the process, because time is money. This contributes to the fact that the worker does not recognize himself in his final product, causing strangeness when he is faced with a commodity “X” in a supermarket, for example, he does not think that that commodity only exists because of his work. He does not remember that he is the only one capable of producing value – his work is what produces value and not the other way around.

In Marx’s (2005) expectation, when an individual seeks to consume the commodity “X” (An iPhone XS Max apple), he wants to have it because it adds some status, some characteristic that will give that individual a social valuation. This enchantment and wonder that the commodity causes in the individual, Marx calls the “fetish[6]” of the commodity.

In our alienating imagination, there will always be a preference for one type of commodity over another, even though both have the same use value, but only one of them gives the status that the individual wants. Referring to the example of the cell phone: If an iPhone SX Max Apple is displayed in one window and in the other window, almost hidden, there is an LG wireless FM cell phone – both with the same use value (making calls), except that the first is a thousand percent more expensive than the second.

But if the two commodities have the same use value, why then does one have more value than the other? What sets your price? What defines its price is the time needed to produce that commodity, that is, it is the human work employed in these commodities. This is what defines real value. Now, what makes one have an exorbitant value in relation to the other is the question of the fetish, it is the question of valuing the individual. So to value the individual, this commodity will be increasingly expensive.

Thus, we can see that:

O valor de uma mercadoria está para o valor de qualquer outra mercadoria como o tempo necessário de uma está para o tempo necessário de trabalho para a produção da outra.[…] Quanto maior é a força produtiva do trabalho, menor é o tempo de trabalho requerido para a produção de um artigo, menor a massa de trabalho nele cristalizada e menor seu valor. Inversamente, quanto menor a força produtiva do trabalho, maior o tempo de trabalho necessário para a produção de um artigo e maior o seu valor. (MARX, 2005, p.164)

It can be seen with this that the merchandise when finished, that is, when it is ready, did not maintain its real sale value, which according to Marx (2005), this value is determined by the amount of work materialized in the product and however, this merchandise acquired an unrealistic, unfounded sales valuation, as if it were not the fruit of human labor and could not even be measured, what he wanted to demonstrate with this is that the merchandise seemed to lose its relationship with work and gain a life of its own.

About this, Marx (2005) says that, at first glance, a commodity seems like a trivial thing and that it is understood by itself, however, from the moment it appears as a commodity, as an exchange value, things change shape- it transforms become something mystical, palpable and impalpable.

All of us, human beings[7], during our life history, have certain things that we place on top of what is most important – that is to value. As an example, we can mention young people from the periphery who sometimes fail to eat well, skipping some meals, getting into debt or even doing illegal things in order to have a fashionable cell phone, or something that is in vogue. For them, a cell phone is everything. It gives status and whenever a new model comes out, they do everything to acquire it. It doesn’t matter to them if the house they live in is bad, if they live in the worst neighborhood in the city, if they eat poorly, if they study in a poor school, because what drives them crazy, bewitched, is a fashionable cell phone. So these people value these commodities as something supreme and will do anything to get them.

Marx (1983), complements[8] this thought by saying that in capitalist society the bourgeoisie creates a fundamental aspect for maintaining its privileges, so this bourgeoisie will also make its values dominant in this society, using ideology to mask existing farm relationships, passing these values on to people, in order to remain in the process of producing and selling goods.

The bourgeoisie values the commodity so much that it becomes a supreme value, the most important thing. However, for the value of this commodity to be accepted by individuals, this value needs to be reproduced on a daily basis. At this stage, marketing, sales strategies and traps enter, making individuals value the merchandise more than the human being. With this, the human being ends up giving way to merchandise, objectifying himself. There is an inversion in the process, where the creator becomes dominated by creation. – The commodity fetish.

A mercadoria é misteriosa[9] simplesmente por encobrir as características sociais do próprio trabalho dos homens, apresentando-as como características materiais e propriedades sociais inerentes aos produtos do trabalho; por ocultar, portanto, a relação social entre os trabalhos individuais dos produtores e o trabalho total , ao refleti-la como relação social existente, à margem deles, entre os produtos de seu próprio trabalho se tornando mercadorias(…) Uma relação social definida, estabelecida entre os homens, assume a forma fantasmagórica de uma relação entre coisas(…) Chamo a isto de fetichismo, que está sempre grudado aos produtos do trabalho, quando são gerados como mercadorias. É inseparável da produção de mercadorias (MARX, 1983, p.81).

It is understood by this that commodity fetishism is the perception of the social relations involved in production, not as relations between individuals, but as the economic relations between money and commodities traded in the market. Thus, commodity fetishism transforms subjective aspects into objective ones.

Through Marx’s concepts about merchandise and fetishism, it is worth mentioning the work of Bauman (2008) in order to work on consumption from another perspective.

Once merchandise fetishism is seen as a process that covers up and masks the effective relationships between men in favor of the relationship between things, Bauman (2008) adds that in the society of consumers, the masking dynamics takes place through the bias of subjectivity.

In this context, Bauman (2008) states that subjectivity is highly associated with the transformation of individuals into merchandise.

Na sociedade de consumidores, ninguém pode se tornar sujeito sem primeiro virar mercadoria, e ninguém pode manter segura sua subjetividade sem reanimar, ressuscitar e recarregar de maneira perpétua as capacidades esperadas e exigidas de uma mercadoria vendável (BAUMAN, 2008, p.20).

It is understood by this that the consumption pattern has become a form of social affirmation, in the integration of certain groups in society. In this way, consumerism represents an important pillar for capitalism. And to maintain the advanced pace of production and profit, a manipulative system is fed, where product obsolescence is motivated by convincing media.

Advertisements filled with ideologies instill in individuals an uncontrollable desire to own a certain good and do not rest until they buy it. However, this desire for possession, this immoderate love for a certain commodity, soon passes due to the launch of another commodity whose characteristics fill the eyes, offering a thousand and one advantages. And so, the modern consumer discards his “old object” (with a maximum of six months or a year), and buys the novelty.

And in this sense, Bauman (2001) comes to tell us that:

Pode-se notar a grande importância do consumo na caracterização da “modernidade liquida”. É por meio dele que aos indivíduos são construídos e transformados constantemente, tornando as identidades individuais passageiras. […] A “sociedade de consumidores” estimula uma estratégia existencial consumista e rejeita outras opções culturais alternativas[…] (BAUMAN, 2001).

The constructed world of durable objects has been replaced by available products designed for immediate obsolescence, that is, products we already buy that are scheduled to be defective. In this sense, thinking about the fascination exercised by merchandise and the volatility of this post-modernity, or liquid modernity, it is clear that identities can be adopted and discarded like a change of clothes.

Commodities become obsolete in a very short time, and in this way objects, as objects of consumption, lose their allure as soon as they are consumed.

We are living in a liquid modernity, where everything flows smoothly, everything is disposable and seems to lose its value. In view of this, I ask: Does this detachment, this lightness with which things are being treated, have any implications for its value, for its price? Will the labor force added to merchandise have less value in this liquid modernity?

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Merchandise fetishism translates into a seductive power that merchandise exerts over individuals, even taking their place. This reversal of roles occurs due to the valuation that occurs with the consumption of the commodity, making its creator not even recognize himself in the product anymore, becoming the thing. Marx (2008) called this objectification: creation takes the place of the creator.

From another perspective, Bauman (2001) underlines about exacerbated consumption, about liquidity that melts everything around, making things and individuals fickle, disposable in a dynamic of consumerism where the promise of the “new” brings happiness and the discard of the “old” a void that must be filled by more consumption.

To maintain this advanced pace of production and profit, the capitalist model adopts a manipulative and alienating system, using the programmed obsolescence of products, where everything consumed loses its value in the short term.

REFERENCES

BAUMAN, Zygmunt. Modernidade líquida. Rio de Janeiro. Editora Zahar, 2001.

BAUMAN, Zygmunt. Vida para o consumo. Rio de Janeiro. Ed. Zahar, 2008.

MARX, Karl. O Capital: Mercadoria. São Paulo: Centauro Editora, 2005.

MARX, Karl. O Capital: Crítica da economia política. São Paulo: Nova cultural, 1983.

MEUCCI, Isabella Duarte Pinto. Revista sem aspas. Disponível em: https://periodicos.fclar.unesp.br/semaspas/article/view/69. Acessado em 03/12/18

NETTO, José Paulo e BRAZ, Marcelo. Economia Política- Uma introdução à crítica. Vol. I. S. Paulo. Ed. Cortez, 2006.

APPENDIX – FOOTNOTE REFERENCES

3. French word meaning out of fashion. It’s not in fashion anymore.

4. http://revistapontocom.org.br/materias/obsolescencia-planejada

5. Trap in the sense of strategy.

6. Fetish: object that is attributed supernatural or magical power and is worshipped.

7. Audio by Professor Edmilson Marques.

8. Audio by Professor Edmilson Marques.

9. https://cafecomsociologia.com/para-entender-de-uma-vez-por-todas-o/. Accessed in 12/02/2018-Quote from Marx, 1983.81.

[1] Post graduation in Education in Environmental Management (2011)-Faculdade Serra da Mesa-FASEM – Uruaçu-Go; Graduate in Biology (2005) – Universidade Federal de Lavras-UFLA; Postgraduate in Teaching Methods and Techniques (2003) – Universidade Salgado de Oliveira – UNIVERSO; Graduate student in Civil Law (2020) – Pontifica Universidade Católica – PUC – Minas; Degree in Pedagogy (2001) – Universidade Estadual de Goiás – UEG – Campus Uruaçu; Bachelor’s Degree in Biology (2004) – Universidade Estadual de Goiás – UEG Campus –Porangatu; Degree in Physics (2012) – Universidade Federal de Goiás – UFG; Law student (2020) – Universidade Estadual de Goiás – UEG Uruaçu campus.

[2] Advisor. PhD in History. Master in History. Specialization in Political Science. Graduation in History.

Submitted: June, 2020.

Approved: November, 2020.