ARTIGO ORIGINAL

ALTMICKS, Alfons Heinrich [1], CANTON, Anayme Aparecida [2]

ALTMICKS, Alfons Heinrich. CANTON, Anayme Aparecida. Kaimbé Art and Culture: The EJA as an influencing agent of handicraft production. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 05, Ed. 10, Vol. 10, pp. 181-200. October 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access Link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/education/craft-production

SUMMARY

The education of Young people and adults (EJA), ethnically differentiated, is a condition for the kaimbé indigenous woman to recognize its potential, as a transforming agent of its community, affirming its cultural identity, in the face of the exclusions that place it on the margins of society. In this sense, these women use the cultural leather of indigenous handicrafts to establish links between Education, Culture and traditional knowledge. Thus, the problem that guides this investigation is limited to the following question: how does the EJA contribute to the Kaimbé indigenous woman recognizing its potential, acting as a transforming agent in society and in her family, enabling changes in behavior, in the face of situations of social exclusion, that marginalize her? In the scope of this question, the primary objective, which is imposed on this investigation, was to analyze the way the EJA helps achieve the ethnic affirmation of female Kaimbé, bringing understanding about the role of indigenous women, as a transforming agent, in their society and in their family. The methodological path adopted was the case study of ethnographic bias, characterized by the understanding of the phenomenon in its normative and cultural field. At the end of this investigation, it was verified the relevance of the EJA, as a maintaining element of ethnic identity and kaimbé female belonging, especially from its proposal to work the elements of kaimbé culture, inserted in the indigenous handicrafts, produced in the Massacará Territory.

Keywords: Education, Youth and Adult Education (EJA), Kaimbé indigenous crafts, life stories.

INTRODUCTION

Showing the work of Kaimbé women means, with regard to the objectives of this research, recognizing the contexts that build the subjects, in the field of Youth and Adult Education (EJA), specifically, with regard to indigenous education and the rescue of a culture that runs the risk of disappearing – since it is a people of rare and practically unknown ethnicity. In addition to cultural rescue, another important factor, in this sense, is the propagation of this culture in the academic sphere, as a record for future research – besides leaving, for the Kaimbé indigenous community itself, the record of its culture for the new generations. That said, it is necessary, in the meantime, to punctuate the role of the Kaimbé indigenous woman as part of a society that still insists on consqueting those who have struggled to reach their place; thus, highlighting the life histories of these women in the course of this work will enable awareness of the factors that contributed to the abandonment of their studies – especially by the social demands, more common to the female universe.

In time, the guide element of this research stands out, which aims to perceive the influence of the EJA on the ethnic formation and belonging of the Kaimbé indigenous woman. The following question was also attempted: how does the EJA contribute to the kaimbé indigenous woman noticing and recognizing their potential, acting as a transforming agent, in society and within their family, enabling the change in behavior profiles, in the face of situations of social exclusion, which place them on the margins of society?

The EJA, offered in the Indigenous Territory of Massacará, within the conventional school activities of the Dom Jackson Berenguer Prado Indigenous State College, is essential for the ethnic legitimation of the Kaimbé woman, endorsing her with knowledge, which allows expressing, in the local handicrafts, the characteristics of her ethnicity, besides constituting an important niche of subsistence for the Kaimbé community. In this regard, it is noteworthy that the didactic-pedagogical orientation of the aforementioned educational institution is in line with the proposals of contemporary Indigenous Education, in order to develop elements of cultural and ethnic valorization, in addition to supporting territoriality and Kaimbé belonging. For this, indigenous handicrafts are used as one of the methodological resources of this type of teaching, in the State Indigenous College Dom Jackson Berenguer Prado; besides enabling the performance of a work activity, in a scarce territory of work opportunities, this mechanism allows the dissemination and, consequently, the legitimation of the Kaimbé culture, since the handicraft products, made by kaimbé indigenous women, are directed to various parts of the state of Bahia.

In this sense, the general objective of this article is to analyze the way in which the EJA, offered at the Dom Jackson Berenguer Prado Indigenous State College, helps achieve the kaimbé female ethnic affirmation, bringing understanding about the role of the Kaimbé indigenous woman, as a transforming agent, in her society and in her family. In the guise of specific objectives, one has: to point out the consonance between the activities developed in the EJA of the State Indigenous College Dom Jackson Berenguer Prado and the proposals of contemporary Indigenous Education; demonstrate that kaimbé indigenous handicrafts, used as a methodological resource in the EJA of the Dom Jackson Berenguer Prado Indigenous State College, represents an important work activity, in a scarce territory of job opportunities, and enables the dissemination and legitimation of Kaimbé culture.

Finally, the relevance of this research lies in the need to understand the EJA, within an ethnic perspective, as an educational instance, which, in addition to instrumentalizing and potentiating the workforce of its students, helps them to understand themselves as beings endowed with ethnic identity and a particular culture. Given the scarcity of literature on the subject, research gains urgency in the academic environment. In fact, it is necessary that education researchers, especially at the level of stricto sensu, awaken attention to the specificities and idiosyncrasies of Indigenous Education. In this sense, we hope that this article can at least provoke interest in researchers in the educational field, so that new investigations can be prepared.

THE KAIMBÉ TERRITORY

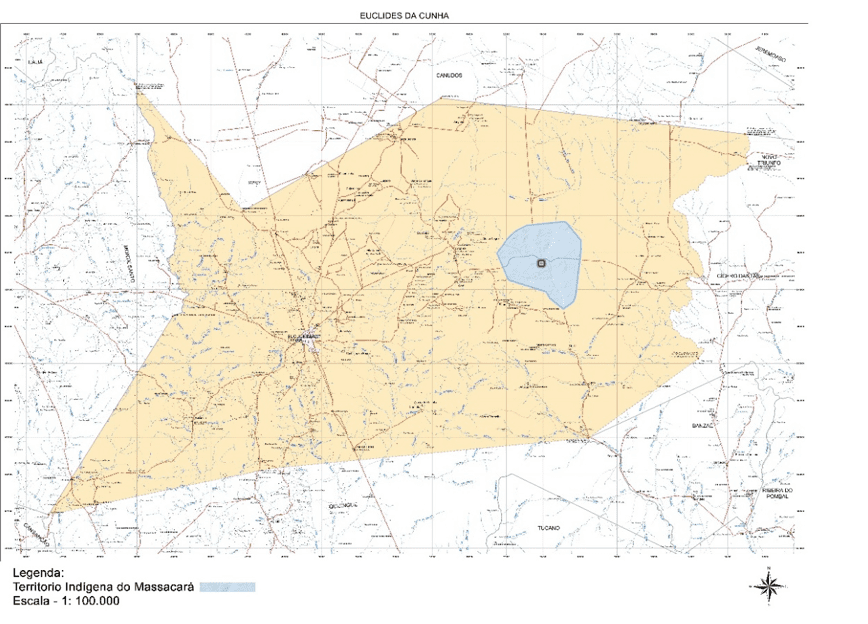

The Indigenous Territory of Massacará occupies 8,020 hectares, demarcated by the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI), in the so-called “Polygon of Bahia Drought” (Polígono da Seca da Bahia), located in the municipality of Euclides da Cunha, Geographic Mesoregion of northeastern Bahia. Within its demarcation, there are about 1,150 Kaimbé indians, distributed in eight populated nuclei: Massacará, which concentrates most of the population, Saco das Covas, Lagoa Seca, Baixa da Ovelha, Icó, Várzea and Outra Banda.

The Kaimbé ethnic group had its recognition in the incipience of the ethnic[3] emergency in 1945, when they were made official, as indigenous, along with remnants of some other ethnic groups, considered already missing (ARRUTI, 1995). This recognition brought only vague promises of demarcation of a future territory to the Kaimbé people. As a result of the recognition, the first post of the Indian Protection Service (SPI) (ALTMICKS, 2018) was installed in the region. In the 1970s, the Kaimbé resumed the struggle for the demarcation of their lands, constricting the Federal Government in 1982 to appoint a FUNAI commission to study the possibility of achieving their own territory (SOUZA, 1996).

In 1992, the Indigenous Territory of Massacará was finally created, through Decree No. 395, of December 24, 1991 (BRASIL, 1991). The demarcation, in yes, was conflicted, especially because there were important disagreements about the real dimensions of the Territory, having as parameter the films, originally supposed in the Royal Charter of 1700, which predicted “[…] a league in court from the Church of the Holy Trinity” for the Kaimbé – about 12,300 hectares. Thus, in 1985, the land survey of the Territory was produced, which suppressed about 4,000 hectares of Kaimbé lands, intensifying tempers between indigenous and non-indigenous peoples. Fourteen years later, without having to reconcile tensions, FUNAI finally promoted the process of disintrusion of non-indigenous peoples from the Massacará Indigenous Territory (REESINK, 1984; OLIVEIRA, 1993; BRAZIL, 2013).

Although, nowadays, the Kaimbé population has its own territory, it is also spread over non-indigenous towns and districts of the region, and many indigenous peoples live in the municipality’s headquarters. Likea, it is possible to find Kaimbé families inhabiting metropolises such as Salvador and São Paulo. The exodus, added to the difficulty of determining objective criteria to attest to their ethnic status, generated the official non-recognition of FUNAI indigenous Kaimbé. Many indigenous peoples who inhabited villages far from the nucleus of Massacará, in addition to those who lived far from the region, were excluded from the process. These people, although they now share the Kaimbé ethnic matrix, they do not appear as such before the State.

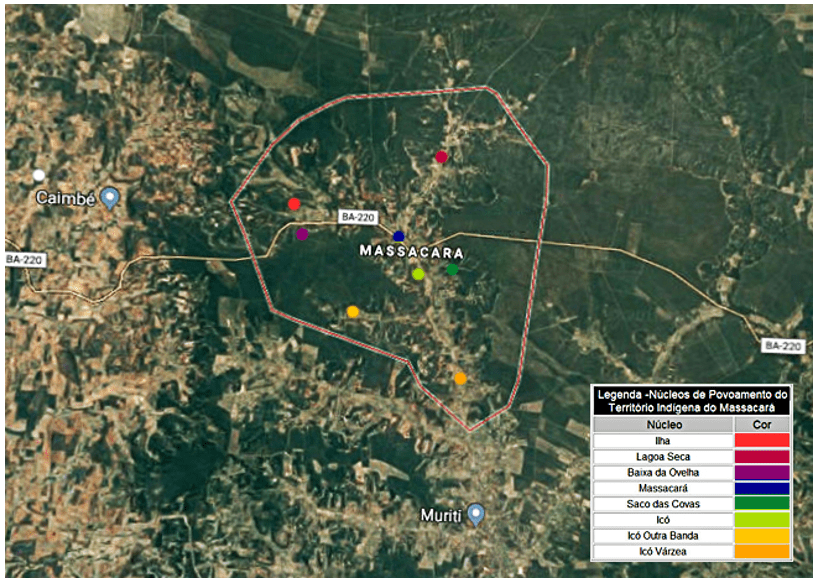

The ubiquity of the Kaimbé Indigenous Territory, in relation to the municipality of Euclides da Cunha, and the distribution of Kaimbé settlement nuclei within the Massacará, are arranged below in Maps 1 and 2:

Map 1 – Location of the Kaimbé Indigenous Territory in the Municipality of Euclides da Cunha, Bahia, 2016

Source: BAHIA, SEI, 2016, adapted by ALTMICKS, 2018.

Map 2 – Distribution of Kaimbé settlement nuclei in the Massacará Indigenous Territory, 2018

The Massacará settlement includes the main indigenous, non-indigenous and indigenous institutions of the territory, such as the FUNAI Post, the Health Post of the Special Secretariat of Indigenous Health (SESAI), the post office, the Kaimbé Cultural Center, the flour house of the Kaimbé Indigenous Association and the State College Dom Jackson Berenguer Prado (CÔRTES, 2010; QUEIROZ, 2013). It has good infrastructure, but there is only the basics, even if the surrounding population imagines and expresses that the Kaimbé are carriers of sophisticated rights and benefits (CANTON, 2018).

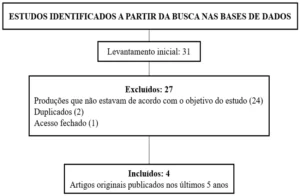

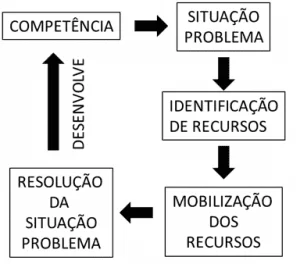

OF THE INS AND OUTS OF RESEARCH

This work constitutes a research of bias towards Ethnography (although it does not constitute, strictly speaking, an Ethnography), with a qualitative character. As a procedure methodology, we used the critical triangulation of information, departing from the documentary analysis, from the consultation of the authors who focus on the theme and the participant observation in the Kaimbé Indigenous Community, in the Indigenous Territory of Massacará, located in the City of Euclides da Cunha, Bahia. The scope of the investigation is to analyze the relations between work, EJA and ethnic identity of Kaimbé women, therefore, the research assumes, since its genesis, the perspective of an analysis of the phenomenon in retrospect, from which it is infered, therefore, that it is a case study.

Merrian (2005) understands that the most important characteristic of the case study is its concrete, because it is a dive, an immersion, in the phenomenic reality. From its perspective, the case study would have four fundamental horizons: 1) the horizon of specificity, because it refers to a singular situation; 2) the horizon of detailing, since it requires a detailed description of the component phenomena of the case; 3) the horizon of heuristics, since the case study focuses on information that cannot be obtained from generalist methodological approaches; and 4) the horizon of induction, since the researcher must infer about the particularities of the case, in order to achieve his broader understanding.

It is noteworthy, in time, that case studies are categorized, as a rule, as field research. According to Gonçalves (2001, p.67): “Field research is the type of research that aims to search for information directly with the population surveyed. It requires a more direct encounter from the researcher.” In other words, according to the author , “[…] the researcher needs to go to the space where the phenomenon occurs, or occurred and gather a set of information to be documented” (2001, p.67).

Fraga (2008) warns of the fact that field research assumes a different typology: ex-post-facto research, action research, participant research, ethnographic research, etc. This investigation, while it is located in an ethnic niche, assumes the character of ethnographic field research, configured in a case study. According to Lüdke and André (1986), ethnographic research is supported by two conceptions of human behavior: 1) naturalistic conception, according to which human behavior is determined – or at least influenced – by the sociocultural context to which it belongs. For this reason, the individuals surveyed cannot be removed from their environment, under penalty of losing the delicate connections between their behaviors and the dynamics that surround them; and 2) phenomenological conception, which supposes to be human behavior always dependent on personal cultural references, the result of the subjects’ experience.

In time, the contribution of Lüdke and André (1986) is significant, regarding the character of a research, these attribute a hybrid nature to qualitative research: on the one hand, it is made of idiosyncrasies, so that a qualitative research differs from any others that have already been done; on the other hand, there are certain common traits in your procedures, which enables your configuration as a specific search category. Qualitative research demands the construction of flexible and aprioristic hypotheses, which do not need to be empirically verified, that is, this category of research is essentially open to changes in its hypotheses, which does not mean, however, that this type of research does not have defined and rigid objectives.

This said, intervention activities were used with the class of students of the EJA, which would use the Kaimbé indigenous handicraft, as a methodological resource, in the classroom, so that during the exhibition and preparation of the same could be approached the life stories of the women of the community and, then, the application of the research questionnaire. However, in a research of this level, sometimes the work can be overarched in certain implications that limit the collection of data in an expected way, conducting the research, to other paths, as in the case of visits to the community.

In this sense, the subjects expected from the research (which would be the women of the Kaimbé people) pass on to the employees, teachers and school management who, in informal conversations, brought the contents that underpined the analysis proposed by the investigation. In addition, one of the chiefs – since the territory is the direction of three chiefs – also collaborated, in the making of this work, with precious information, obtained by unstructured interviews. The said chief is the oldest in the village and has been committed to collaborate with information to researchers, so that the Kaimbé culture is maintained and propagated, thus reaching other indigenous communities and more researchers.

In the process of performing the moments of intervention and application of research instruments in an indigenous community, it is necessary to have written consent, upon presentation of the project to the territory’s cacicado. In the case of this investigation, at the suggestion of the elderchief, a meeting was scheduled with the three ethnic chiefs, for presentation and evaluation of the investigative proposal, to be carried out. Although the above-mentioned meeting has not yet been realized, until this stage of the investigation, there was only consent for visits and informal conversations with the subjects of the investigation, which are, a priori, the management, teachers and employees of the State Indigenous College Dom Jackson Berenguer Prado.

That said, as a result of these preliminary visits to the Massacará Indigenous Territory, it was possible to know the facilities of the College and some of the history of its foundation. In addition, there were conversations, with the government of the institution, about the indigenous curriculum and the teaching dynamics. Moreover, through contact with teachers, it was possible to know the disciplines and content adequacies, inserted in the curriculum, through the maintenance of the culture of this community.

In time, still regarding the conversations with the elder chief, it was possible to highlight the shared knowledge about legends and cosmogonia Kaimbé, which are part of the literary universe of this ethnicity. In addition, it was possible to know about the stories of demarcation and possession of the current lands. We were allowed to enter the school, when the management gently presented the facilities, recently equipped and renovated. The look at the indigenous woman and her handicrafts occurred through visits to the Kaimbé Indigenous Cultural Week, in which contact was made with the work of these women.

Thus, this research proposes a study carried out in the Indigenous Territory of Massacará, Kaimbé community. The locus of the research is the EJA class of the State Indigenous College Dom Jackson Berenguer Prado. The research subjects are Kaimbé indigenous women, EJA students, kaimbé craft manufacturers. The technique used in this investigation was neutral systematic observation, developed between August and November, 2018.

EJA, WORK AND INDIGENOUS IDENTITY FEMALE KAIMBÉ

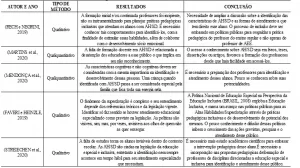

It was through many struggles that the current Indigenous Legislation was reached, which guarantees the right of indigenous peoples to a differentiated education that respects their ethnic origins and culture. In this sense, their demands gave rise to programs conducted both by actions of states and municipalities and by non-governmental actions to support indigenous peoples, being the leader of the new paradigms for Brazilian indigenous education (COLLET; PALADINO; RUSSO, 2014). Moreover, indigenous peoples have the right to cultural difference, that is, the right to be indigenous and to remain as such (BRASIL, 2011), breaking with an integrationist tradition, which saw indigenous peoples as members of a supposed national homogeneity, bearers of a common Brazilianity, and, therefore, capable of being incorporated into Brazilian social dynamics, which would be up to the Union to promote , in addition to protecting and tuteing them (GRUPIONI, 2002; 2006).

In other words, indigenous peoples have their rights guaranteed by the Constitution, which recognize sholdterritory, housing, forms of production, preservation of the environment and ethnodevelopment, in addition to the use of their original languages and their own learning mechanisms, and the State is given the duty to protect its cultural manifestations (BRASIL, 2011). These rights have given the possibility for indigenous schools to be an instrument for valuing indigenous languages, knowledge and traditions, no further than the imposition of the cultural values of the surrounding society. In this process, indigenous cultures, properly valued, should be the basis for the knowledge of the values and norms of other cultures.

After the enactment of the Law of Guidelines and Bases of National Education (LDB) (BRASIL, 1996) indigenous schools were able to exercise the function of facilitating cultural autonomy, favoring indigenous self-determination. Numerous changes have occurred in the process of structuring indigenous education, the LDB, for example, recommends that education systems be articulated, as well as integrated teaching and research programs, which target indigenous populations, with the objective of developing specific curricula, whose contents include all cultural baggage, characteristic of each indigenous community.

The National Education Plan (PNE) (BRASIL, 2014) presented guidelines for Indigenous Education, in one of its chapters, to be achieved in the short and long term, with regard to the objectives and goals. In addition, it has created specific programs to serve schools in indigenous areas, implementing funding lines for education. In collaboration with the States, the Union was responsible for equipping schools with adequate pedagogical and didactic support, equipment and physical adaptations, in addition to others, to adapt the programs, already existing in the Ministry of Education, in terms of aid to the development of education, in the state education systems, whose legal responsibility for indigenous education is designated.

Still in this regard, regarding language, what is observed is that there are still monolingual schools, which do not have in their curriculum native characteristics to be worked in the school environment, without physical, pedagogical structures and with few didactic resources, making it impossible that the realities presented in textbooks can be reinterpreted based on the reality experienced culturally, even in the midst of struggles to have the right to bilingual and intercultural education.

Grupioni (2002) draws attention to an important issue: with regard to the changes demanded by indigenous peoples, government agencies, in the most varied spheres, have shown little permeable. However, indigenous peoples continue their journey amid much struggle to make it clear that, only through an education that takes over the culture, appropriating it, with the participation of management and teachers, who share this same ideal, and also involving the community, can the autonomy of the peoples from which the original characteristic was taken for so long be guaranteed. Indigenous peoples have been resignifying their Education, thus ensuring the valorization of their historical knowledge, deconstructing the old standards that have been imposed on them for a long time. It is necessary, however, to recognize the differences and needs of each people, thus guaranteeing the right to have their knowledge recognized respecting ethnic differences (SOUZA, 2016).

Through these changes, formal education is understood as a facilitating mechanism for communication with non-indigenous communities, meeting the demands of the indigenous peoples presented, thus starting specific projects to meet these realities, based on respect for culture, history, interculturality and variety of languages, as well as the principle of ethnic diversity (BATISTA, 2011; SANTANA, 2011). In this sense, it was essential that the community of the State Indigenous College Dom Jackson Berenguer Prado brought, to the school environment, a vision of practices that stimulated and developed the feeling of belonging to their Kaimbé ethnicity so that they could prepare the younger ones to fully assume their indigenous condition.

This initiative was fundamental to give back to the older people in the village, confidence and self-esteem, so that they would feel encouraged to resume their studies and position themselves in their community as subjects belonging to it; to teachers, the task of manifesting this topophilia and territorieity, inserted in the daily life of the school, in its daily activities. In the meantime, it is necessary to emphasize the fact that the Kaimbé were integrated into the surrounding society with their aspects diluted with regard to the material and symbolic aspects of their culture, that is, their Indianity has undergone a process of ethnic reconstruction, in which their indigenous identity is reconstituted from the feeling of belonging. That said, the Kaimbé affirm their ethnic belonging no longer as original Kaimbé Indians – pre-Columbian – but as contemporary Northeastern Indians, who live with society around them, interacting and exchanging cultural, material and symbolic experiences.

With regard to pedagogical practices, it is perceived that they are holistic, that is, they are not restricted to knowledge and collectively seek their elaboration, always interspersing teaching and learning with experiential characteristics, in their school in which spaces and pedagogical times have no clearly defined boundaries. Thus, the space of the indigenous school is not exhausted on the walls of the classrooms, the time of the indigenous school is not situated in the interval between the sirens of entry and exit, of the students, of the school unit building, all happening in perfect harmony, uniting school and community. Therefore, analyzing the sociocultural aspects of the subjects of the EJA is of fundamental importance to understand and relate the phenomena studied, as well as their connection with the daily processes of the researched community.

In addition to the debate, the contributions of Barcelos (2012), in his perspective education was built in the midst of a scenario of intersections, encounters and cultural and ethnic confrontations, drawing attention to the fact that changes and adaptations to the Curriculum do not always take place peacefully. The MEC when it confers legitimacy to an Education that recognizes and defends cultural diversities sounds contradictory when establishing Curricular Parameters without taking into account the specificities of each region and people. The Education of Young people and adults itself, in this sense, cannot be seen merely as a facilitator of the insertion of the Young and Adult in the labor market, since there is a historical dichotomy, already studied by Freire, in forming this subject for work and forming its general character inherent to the school environment. This is an old discussion, but it can be perceived nowadays in the merely technicist behavior that Freire (1997) drew attention to. Currently, Soares (2005) states that it is an influence for the elaboration and planning of public policies for the Education of Youth and Adults nowadays.

As for the context of Indigenous Education of Young people and adults, its formative character carries, in its scope, extremely emancipatory sociocultural factors, for cultures whose history was of denial and ethnic leveling. It is known that indigenous peoples have not been able to achieve emancipation and appropriation of their rights, without struggle and resistance. In the school environment, this reality has not been different, because the struggles for ethnic recognition are perpetuated in educational institutions. The indigenous school space has been used as a field of cultural action and ethnic legitimation, as occurs in the Indigenous Territory of Massacará, in the State Indigenous College Dom Jackson Berenguer Prado.

That said, one of the objectives of this work is to describe the experiences of Kaimbé indigenous women, in the backlands of Bahia, in the face of the numerous difficulties and situations of exclusion they experience, as well as their determination to build and maintain their families, even with social implications, which caused them to leave school too early to be able to provide for and maintain their families. Kaimbé women have struggled to maintain their livelihood. One of the ways in which they manage to maintain their families is indigenous crafts, an ancestral knowledge that has been passed down for generations. Indigenous women have also gained space in their communities, occupying places such as the cacicado and the magisterium, in addition to other prominent activities.

In this regard, in the Indigenous Territory of Massacará, the Cacicado is three times as triple, that is, there are three chiefs in the community, who carry out their activities according to each need presented. The indigenous school, however, has, for the most part, female employees (including management, technical staff and indigenous teachers with specific training for indigenous education and higher education). This is a relevant factor, because it was observed that, in addition to being women, most of them perceive that the youth of the community has sought knowledge and positioned itself within its context, performing activities that contribute to intellectual growth and social development.

It is noteworthy that indigenous women do not recognize themselves within a feminist concept, because the agendas and molds of Western feminism do not match their ideals of struggle. They prefer to affirm that the struggle of indigenous women is focused on the well-being of the community in general, and not just for women. An expression used, among them, is that they “recognize themselves” as active indigenous feminine, which seeks improvement in health conditions, education and territorial demarcation.

Another characteristic is also a great thing in Massacará: the younger ones have been committed to maintaining and disseminating the Kaimbé culture so that it does not become forgotten by future generations. The main economic activities developed in the Indigenous Territory of Massacará are traditional family farming, the State, and the breeding of birds and goats. According to Queiroz (2013), the Kaimbé most recently began an organization process to deal with the economic and sociopolitical difficulties they went through; the Kaimbé people of Massacará, who gave rise to the Massacará-Kaimbé Association (AMK) (collective gardens); Kaimbé Várzea Association (AKAVA) (beekeeping); and Lagoa Seca Association (ALS) (subsistence agriculture). Abreu (2013) and Altmicks (2018) also identified economic initiatives in the fields of handicrafts and cultural manifestations.

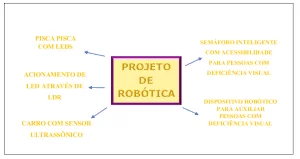

Kaimbé women produce garments and decoration, manufactured with seeds from the region and with crauá straw. The core of handicraft production is configured in the classes of the disciplines “Indigenous Language” and “Identity/Culture”, taught at the State College Dom Jackson Berenger Prado. The handicrafts, made by these women, in the context of the research, is used in the classroom as a facilitating mechanism of knowledge, which allows to know the stories of women subjects of Youth and Adult Education, in the Kaimbé territory in Euclides da Cunha, Bahia, Brazil. The work, in this sense, consists of observing, in the evening classes, in the arts discipline, the Kaimbé crafts and promoting the debate with the help of interviews and presentations to record the stories of these women in order to record this culture[4].

RESEARCH RESULTS

As the first result of the investigation, carried out at the State Indigenous College Dom Jackson Berenguer Prado, we highlight the most atissued knowledge about the history of the educational unit, its faculty and its staff. It is said to have been founded in 1968 under the name “Cenesista College of Massacará”. His activities took place in a shed, with three improvised rooms, which accommodated the classes from 1st to 9th grade. At its origin, the college was not dedicated to the segment of ethnic education, since the village of Massacará had not yet been recognized as indigenous territory. With this recognition, the educational unit came to be called “Dom Jackson Berenguer Prado Indigenous Municipal Educational Center”, in honor of the eponymous Catholic bishop, very influential in the region, at the beginning of the 20th century (UFBA, 2012). The institution remained municipalized until 2012, when it was expanded and stateized, starting to include the stages of High School and Youth and Adult Education (EJA), in addition to the Todos Pela Literacy Program (TOPA). Since that time, the State Indigenous College Dom Jackson Berenguer Prado is subscribed to the Regional Directorate of Education (DIREC) 12 – Serrinha, responding directly to the Department of Education of the State of Bahia (SEC) (ALTMICKS, 2018).

The Dom Jackson Berenguer Prado Indigenous State College has an Indigenous School Pedagogical Political Project (PPPEI), updated in 2015. The preparation and updating of the PPPEI had the intense participation of the entire Kaimbé community, which configured it to the intercultural values proposed in the training project for Indigenous Education. In practice, the College’s PPPEI has listed important objectives regarding Kaimbé cultural integration, promoting the appreciation of the ethnic identity of community members (ALTMICKS, 2018).

In the scope of these objectives, the disciplines “Indigenous Language” and “Identity/Culture” emerged, articulating the cultural proposals of the College and the central axis of its pedagogical activities. These disciplines subsidize most of the projects developed at the Dom Jackson Berenguer Prado State College, translating the cultural and territorial dynamics of the Kaimbé people. The zenith of this articulation takes place in October, in which Kaimbé teachers and students perform the activities of the Kaimbé Indigenous Culture Fair[5] (ALTMICKS, 2018).

It was possible to perceive the sharpness of the role of Kaimbé women in Indigenous Education, since they constitute a majority, in the aforementioned institution. In this sense, it was noted, through conversations with the management of the institution, that there is agreement between the proposal for Indigenous Education and the pedagogical didactic mechanisms, which direct the activities of the College, in the sense of valuing the culture of this ethnic group.

In time, another relevant result of the research stands out, the contact with the stories of the Territory, through the elder chief, who spoke of the struggle of his people for the possession of the lands they currently occupy, as well as their trajectory of struggles and denial of indigenous rights. Moreover, the choice to work the indigenous female Kaimbé was strengthened as it was observed how much women, of this ethnicity, have been able to stand out inside and outside the community, with handicrafts as a mechanism for propagating ancestral culture, being also included in the curricular context, as a component of the study of indigenous culture[6]. In youth and adult education, it was also observed that many women, the oldest in the village, had their studies aborted (or could never be in a school), because they remained much of their childhood and adolescence without a fixed place of residence, because of conflicts over land demarcation.

The Education of Indigenous Youth and Adults contributes, greatly, so that indigenous women “empower” their culture, acting as an agent of knowledge multiplication and preservation of their values and culture, positioning themselves, in society, as a subject with belonging, leaving a marginalized condition (commonly faced by the literate subject), being able not only to act in their community, but also in their family context, , acting in a way that encourages young people.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The Education of Young people and adults supposes subjects who, for some reason, have been denied their rights, and it is therefore important to understand and know their stories. Kaimbé indigenous women, for years, suffered even more in their realities because they belong to a marginalized ethnicgroup. In the midst of struggles, they managed to maintain their values and culture, protecting their families with hard work and endurance. They are women who value and try to maintain their culture and history, gaining more and more prominence within their communities, acting significantly and conquering their place, in institutions, universities and in the hierarchical command of their ethnicity, after all, one can see, today, kaimbé indigenous women, gaining respect thanks to much work and dedication. The knowledge, passed in an ancestral way and that brings all ethnic baggage, EJA. Therefore, it is imperative that they be added to the curriculum for Indigenous Education.

Even with all the difficulties presented, Kaimbé indigenous women have walked with persistence and determination, making it clear that, as they assume their culture and craftsmanship, they experience empowerment and ethnic affirmation. In this sense, it is necessary that not only the teachers and students of the EJA, of the State Indigenous College Dom Jackson Berenguer Prado, be part of this struggle, but that the whole community be involved, with looks and practices focused on the need to respond to their needs, contributing collectively to the formation of the autonomy of a people, which was mischaracterized for a long time.

Many achievements can be enumerated, in the contemporary scenario of Indigenous Youth and Adult Education, especially regarding the proposition of new paradigms, which may embody a significant change from an educational model “for Indians”, towards an indigenous educational model (BERGAMASCHI, 2008). If, on the one hand, education for Indians historically presented a source of values inculcated to native populations; currently, indigenous education has been carried out, in order to resignify their realities, universalizing teaching and guaranteeing them the right to value their knowledge, enabling in the field of Indigenous Education a new look at ethnic educational needs.

However, much still needs to be done so that indigenous peoples can guarantee their rights without no longer going through situations of exclusion and prejudice. Violence is constant and still a cruel reality. Education, in this context, empowers the indigenous people of knowledge that contributes so that they have an understanding of their rights and can consciously fight for them; the school, in this process, needs to encourage these EJA subjects in the de facto sworn in of the rights that are theirs.

REFERENCES

ABREU, Sônia. O legado dos índios Kaimbé de Massacará na história e na cultura da atual Euclides da Cunha. Euclides da Cunha, 2013, 26 f. Monografia de Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso (Licenciatura em História). Departamento de Ciências Humanas e Tecnológicas, UNEB, Campus XXII, Euclides da Cunha.

ALTMICKS, Heinrich Alfons, Etnoepistemologia indígena: território e identidade na pesquisa docente Kaimbé. Euclides da Cunha: Farol do Conhecimento, 2018.

ARRUTI, José Maurício Andion, Morte e Vida do Nordeste Indígena: a emergência étnica como fenômeno histórico regional. Estudos Históricos – Rio de Janeiro RJ. Volume 8 n° 15 ,1995 págs.57-94.

BAHIA, SEI, Superintendência de Estudos Econômicos e Sociais da Bahia. Mapas estaduais, regionais e municipais. 2017. Disponível em <http://www.sei.ba.gov.br/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1856&Itemid=496> Acesso em 13 jan. 2018.

BARCELOS, Valdo. Educação de Jovens e Adultos: currículo e práticas pedagógicas. 3.ed./ Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 2012.

BATISTA, Hildonice de Souza. Memórias indígenas: novos valores para uma educação etnorracial. GEPIADDE, Itabaiana, 10, p. 28-43, Jul./dez. 2011.

BERGAMASCHI, Maria Aparecida; SILVA, Rosa Helena Dias da. Da escola para índios às escolas indígenas. Presente! Revista de Educação. Ano 16, nº 63, p. 22-31, dez / 2008.

BRASIL, Presidência da República. Decreto nº 395, de 24 de dezembro de 1991. Homologa a demarcação administrativa da Área Indígena Massacará, no Estado da Bahia. 1991. Disponível em < http://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/decret/1991/decreto-395-24-dezembro-1991-449607-publicacaooriginal-1-pe.html> Acesso em 28 jul. 2017.

BRASIL, MEC (Ministério da Educação). Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. 1996. Disponível em: <http://portal.mec.gov.br/seed/arquivos/pdf/tvescola/leis/lein9394.pdf>. Acesso em: 2 jan. 2018.

BRASIL, MEC (Ministério da Educação). Plano Nacional de Educação (2014-2024): Lei nº 13.005, de 25 de junho de 2014. Aprova o Plano Nacional de Educação (PNE) e dá outras providências. Brasília: Câmara dos Deputados, Edições Câmara, 2014. (Série legislação; n. 125). 86 p.

BRASIL, Ministério Público Federal MPF. Ação civil pública com pedido de decisão liminar em desfavor da FUNAI – Fundação Nacional do Índio. Paulo Afonso: mimeo, 2013.

BRASIL, Presidência da República, Casa Civil. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil: promulgada em 5 de outubro de 1988. São Paulo: Atlas, 2011. 126 p.

COLLET, Célia; PALADINO, Mariana; RUSSO, Kelly. Quebrando preconceitos: subsídios para o ensino das culturas e histórias dos povos indígenas. Rio de Janeiro: ContraCapa, 2014. (Série Traçados, 3).

CÔRTES, Clélia Néri. A educação é como o vento: os Kiriri por uma educação pluricultural. Salvador, 1996. Dissertação (Mestrado em Educação). Faculdade de Educação, Universidade Federal da Bahia.

FRAGA, Elizeu Romero Barbosa. Percursos da formação em docência: o desafio da iniciação à pesquisa. Educar. Belo Horizonte, V. 02, nº 04, pp. 38-63. Jul/Dez. 2008.

FREIRE, Paulo. Pedagogia da Autonomia: Saberes Necessários à Prática Docente. Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra.1997.

GONÇALVES, Elisa Pereira. Iniciação à pesquisa científica. Campinas, SP: Editora Alínea, 2001.

GRUPIONI, Luís Donisete Benzi. Quem são, quantos são e onde estão os povos indígenas e suas escolas no Brasil? Brasília: MEC, 2002.

GRUPIONI, Luís Donizete Benzi (Org.). Formação de professores indígenas: repensando trajetórias. Brasília: MEC, 2006. (Col. Coleção Educação para Todos; 8).

LÜDKE, Menga; ANDRÉ, Marli E.D.A. Pesquisa em Educação: Abordagens qualitativas. São Paulo, E.P.U., 1986.

MERRIAM, Sharan B. Qualitative research and case study applications in education: revised and expanded from case study research in education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 1998.

OLIVEIRA, João Pacheco de. Atlas das terras indígenas no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: PETI, 1993.

POVOS INDÍGENAS, 2018

QUEIROZ, Carine Monteiro de. Brincadeiras no território indígena Kaimbé (Dissertação (mestrado). Universidade Federal da Bahia. Instituto de Psicologia, 2012.) Salvador, 2012. Disponível em: https://pospsi.ufba.br/sites/pospsi.ufba.br/files/carine_monteiro.pdf Acesso em 17 jul. 2018.

QUEIROZ, Carine Monteiro de. As crianças indígenas Kaimbé no semiárido brasileiro. In: CÉSAR, América Lúcia; COSTA, Suzane Lima (Org.). Pesquisa e Escola: experiências em educação escolar indígena na Bahia. Salvador: Quarteto, 2013. 7-20 p.

REESINK, Edwin Boudewijn. A Questão do Território dos Kaimbé de Massacará: um levantamento histórico”. Gente, Revista do Deptº de Antropologia-FFCH/UFBA. Salvador, 1, nº 1, pp. 125-137, Jun-Dez de 1984.

SANTANA, José Valdir de Jesus. Reflexões sobre educação escolar indígena específica, diferenciada e intercultural: o caso Kiriri. C&D-Revista Eletrônica da Fainor, Vitória da Conquista/BA, 4, n.1, p.102-118, jan./dez. 2011.

SOARES, L.J.G. As políticas de EJA e as necessidades de aprendizagem dos jovens e adultos. In: RIBEIRO, M.V. (org.). Educação de Jovens e Adultos: novos leitores, novas leituras. Campinas: Mercado das Letras 2005.

SOUZA, Bruno Sales de. Fazendo a diferença: um estudo da etnicidade entre os Kaimbé do Massacará. Salvador/BA, 1996, 164 f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Sociologia). Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas, Universidade Federal da Bahia.

SOUZA, Maria Luiza de; SOUZA, Arissana Braz Bomfim de; QUEIROZ, Carine Monteiro de (Orgs.). De tempos em tempos: nossas histórias Kaimbé. Salvador: EDUFBA, 2010. (Col. Mestres e Contadores de Histórias).

TRIVIÑOS, Augusto Nibaldo Silva. Introdução à pesquisa em ciências sociais; a pesquisa qualitativa em educação. São Paulo, Atlas, 1987.

UFBA, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Programa Multidisciplinar em Estudos Étnicos e Africanos, Observatório da Educação Escolar Indígena. Projeto Yby Yara. 2012. Disponível em < http://www.observatorioindigena.ufba.br/> Acesso em 20 jun. 2018.

APPENDIX – FOOTNOTE REFERENCES

3. In the 19th century, the state began a policy of “erasing” indigenous ethnic groups in the Northeast, whose purpose was to declare them fully integrated with non-indigenous or even extinct populations. In the 20th century, the academic interest in the indigenous issue was evoked, which contributed to the “discovery” of remaining groups of the Fulni-ô, Kambiwá and Pankararu, Kariri-Xocó and Xukuru· ethnicgroups· Kariri, in northeastern Brazil. Raised to the condition of “remnants”, these ethnic groups incited the movements for the legitimation of their Indianities, resulting, in the 1970s and 1980s, with the support of other indigenous ethnicgroups in the process of the “Ethnic Emergency”.

4. It is worth mentioning, in the meantime, that with regard to field research, in an indigenous locality, there are some specificities that made it impossible to apply the interviews in the first stage, having only observation visits, without intervention in the indigenous space, which can only happen through the presentation of the master’s project to the cacicado and release it to carry out the research , for this reason this work is based only on data from these observations without interaction with the subjects of the EJA directly.

5. The Kaimbé Indigenous Culture Fair has been held without external collaboration and is fundamental to the spread of Kaimbé culture, as well as to discuss the urgent issues that spring from the Massacará community. At the event, the works resulting from the activities carried out by the students and teachers of the Colégio Estadual Indígena Dom Jackson Berenguer Prado are presented: music, theater, poetry, dance, crafts, rites and tastings of indigenous cuisine.

6. There is a false belief that indigenous communities are sexist, in their behavior, however, the Kaimbé community has shown a completely differentiated behavior. Indigenous women have taken over their place in the community and beyond, fighting for their rights, seeking improvement and training to act in the most varied areas.

[1] Graduated in Social Communication (UCSal) and Pedagogy (FAZAG). Specialist in Methodology and Didactics of Higher Education (UCSal), in Education and New Technologies (ESAB), in Ludopedagogy (FETREMIS), in Special Education and Institutional and Clinical Neuropsychopedagogy (FACELI), in Education and Human Rights (UFBA) and in Open and Digital Education (UFRB). Master of Education Sciences (USC). Master in Territorial Planning and Social Development (UCSal). PhD in Education and Contemporaneity (UNEB).

[2] Graduated in Pedagogy (FAZAG). Specialist in Clinical, Institutional and Hospital Psychopedagogy (FVC). Master’s student in Youth and Adult Education (UNEB).

Sent: March, 2020.

Approved: October, 2020.