ORIGINAL ARTICLE

ANTUNES, Maria de Fatima Nunes [1], GUGLIELMI, Juçara [2], ARCARI, Inedio [3]

ANTUNES, Maria de Fatima Nunes. GUGLIELMI, Juçara. ARCARI, Inedio. Reflections on paradigms based on common sense and scientific knowledge. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 05, Ed. 08, Vol. 05, p. 57-63. August 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/education/based-on-common-sense

ABSTRACT

In the education of a country, the first bases of reflection on paradigms are founded, this being the first basis of reflection that extrapolates the family’s convictions. The student is then exposed to a wide variety of truths, statements from different cultures and ways of life. Therefore, this article intends to weave some reflections on the paradigms related to common sense and science, discussing aspects related to the environment experienced by teachers and students according to the literature. The study was based on bibliographic research, intertwining and discussing the issue of paradigms, which are witnessed in the day to day of the classroom. It was concluded in these reflections that the traditional way of presenting education surrounded by paradigms, goes through some discussions that have gradually caused a rupture in this mode of education, thus rebuilding new paradigms.

Keywords: Common Sense, Paradigms, Truths, Education.

1. INTRODUCTION

When talking about change in education, it seems to be something very simple, but when rescuing the history of education, one realizes that it is not so easy to change thoughts, values, beliefs of a people, since most of those involved believe in the knowledge of a community, as understood by Alves (2005) when stating that, even if he prefers not to define, he simply says that common sense is what is not considered science, and this includes all day-to-day deeds, as well as the ideas and hopes that override life.

In this way, common sense works very well to live as a family, especially when it comes to the values and culture of a particular group in society, as each person has their conviction about a certain concept. However, the existence of a ready and finished truth is debatable, as it is vulnerable to the constant transformations of a certain concept, from a particular point of view.

Bringing to the reality of the classroom, students question and discuss the most diverse types of knowledge experienced in their daily lives. They start from their imaginations, fundamental aspects for the construction of a knowledge that is not yet a consolidated truth. It is not healthy for the teacher to approach his ideals and impose them so that they overlap the thoughts of the students, because the imposition can induce him not to be reflective, autonomous and critical. About the concept of truth Foucault (1979) says that not everything has the absolute truth, but at all times and places there is a truth that needs to be discovered, however it is only there asleep, waiting for someone to unravel it. However, it is up to us to identify it in the right way with the right instruments and angles, because it is present somewhere anyway.

Starting from the premise that not all knowledge is true and in some situations they are still ignored by scientists, from recent research carried out by ethnoecologists and ethnobiologists in traditional communities, who seek to rescue and value this knowledge, new alternatives and reflections that oppose the current paradigms and have been provoking positive effects for scientific knowledge. In this perspective, Dickmann and Dickmann (2008) indicate that scientific knowledge is that which is structured, formulated and published in academia. The result, for the most part, of reflections by leaders from the middle class who curiously dedicate themselves to the situations of the poorest in order to analyze them. Even though it is a particular way of characterizing itself from the class point of view of society, it does not fail to issue an opinion on the differentiation of common and scientific sense.

Faced with the paradigms interconnected with scientific knowledge, the figure of the teacher emerges, leading this change of thought, breaking the paradigms that have been established for a long time. This is what is called traditional education, where the teacher-student relationship is marked by the authoritarianism of the former in relation to the latter. In this perspective, only the teacher has the knowledge to teach, because the student’s role is solely to receive the knowledge transmitted by the teacher, so silence in the classroom is imposed by the teaching authority.

2. DEVELOPMENT

The paradigm is what people believe to be true of a practice based on their realities with or without scientific experimentation. Moraes defines the paradigm as a “[…] constellation of conceptions, values, perceptions and practices shared by a scientific community, which shapes a particular vision of reality, which constitutes the basis of the way the community organizes itself” (MORAES, 1996 apud BEHRENS, 2005, p. 26).

In this way Moraes (apud BEHRENS, 2005) evaluates the concept of paradigm on a structure of social reality with which he establishes as truths established in that particular space-time.

According to Kuhn (1991), paradigms are scientific achievements, which aim to provide model problems and solutions for a particular community practicing a science, being universally recognized over a period of time. The paradigm norm emerged from the experiences of Kuhn (1978, p. 260), in which “[…] scientific knowledge, like language, is intrinsically the common property of a group or else it is nothing”. However, to understand it, it is necessary to know the historical context of the groups that create and practice it. Kuhn establishes an interesting form for the concept of paradigm, bringing the scientific knowledge, more elaborated, of a social group that translates as a set of accepted truths.

According to Morin’s interpretation (2000), we live in a time when we have an old paradigm and principle that forces us to separate, simplify, reduce and formalize, and that prevents us from conceiving the complexity of the real. In this way, it is clear that conceptions of truth are protected by a commitment agreed upon by a certain social group.

Still in this line, Morin (2000) explains that paradigms are principles of principles, considering them as master foundations that control our spirits and command theories, unconsciously.

This way of thinking forges and makes us believe in a social structure managed by a set of truths that guide the conscience and the spirit of coexistence in society.

In this sense, Cortella (apud REVIDE, [S.d.], digital text) states that in a world that is undergoing constant change, including in the area of paradigm belief, it is necessary: “to teach what you know, practice what you teach and ask what is ignored”. In addition, we need to be aware of the changes that occur in the world to know which ones to accept and reject. This situation is very representative of what governs the educational sector, the basis of education, causing profound transformations and signaling a rupture in what is considered common sense and scientific knowledge, transforming paradigms.

According to these concepts above and due to the need for new paradigms, teachers seek innovations through their pedagogical actions. The teacher’s task was once to transmit knowledge, while the student was submissive to this situation, whose approach became traditional.

Conservative paradigms focused on imposed truths, passed on content, where the student did not have the power to give his opinion. This practice brought to the student a decorative ability, in which the teaching was independent of the student. Moraes (1997) already mentioned that teaching is practiced through lectures, introduced by reading exercises and copies. And based on efficiency and standardization, they are structured with schedules and curricula, rigid and predetermined. With students segregated by age, in compartments organized by rows, living in a controlled environment on a single and undifferentiated basis.

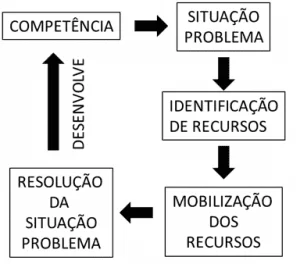

In the idea of overcoming the paradigms mentioned above, the Innovative Paradigms arise, where teachers are challenged to seek new practices to exercise teaching. The student is seen as critical and is involved with the production of knowledge; has freedom of thought. Classroom methodologies for research and innovative ways to promote student learning are expanded. Cortella rightly guides that the school has to be able to follow the changes that occur simultaneously. This is because not everything that comes from the past needs to be kept in the present. The school needs to know how to distinguish what comes from the past and what can be carried forward, in a traditional way, from what must be abandoned because it is archaic.

In this analysis of paradigms, two aspects appear, in which in one, the teacher is the center of truth in a conservative context and in another, however, in the humanist approach he leads learning through innovative means capable of arousing curiosity and motivation in the student. In the traditional methodology, classes are expository and the student needs to read and memorize the contents worked, while in the humanist approach, experiences are analyzed and taken as discussions for learning in an innovative way, using resources and debates between groups of students within the classroom, that is, knowledge is constructed.

It is necessary to emphasize education within the context in which children are inserted, so that there is meaning and learning relationships are effective. According to Morin, about this learning, he presents that knowledge is a reflector of the external world. “All perceptions are, at the same time, translations and brain reconstructions based on stimuli or signals captured and coded by the senses” (MORIN, 2000, p. 19-20).

Thus, it is possible to agree that knowledge is the result of the interpretation that the human being makes about a certain reality from his point of view, with some systematization of ideas, in this way, understanding a little more the process of production of knowledge by the students. Morin develops critical theories by creating profound ideas:

Daí decorre a necessidade de destacar, em qualquer educação, as grandes interrogações sobre nossas possibilidades de conhecer. Pôr em prática estas interrogações constitui o oxigênio de qualquer proposta de conhecimento. […] O conhecimento do conhecimento, que comporta a integração do conhecedor em seu conhecimento, deve ser, para a educação, um princípio e uma necessidade permanentes (MORIN, 2000, p. 29).

Considering the approaches mentioned by the cited authors according to the concepts of Paradigm and the influence on the educational process, it was possible to critically analyze each concept and perceive its possible applicability in the classroom. In this sense, it is understood that the Innovative Paradigm challenges education professionals to develop teamwork, because in the teaching practice, the teacher needs to remain in the dynamics of developing actions that promote students’ criticality and reflection.

3. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The paradigms are visible to our eyes, as education professionals, even so, some teachers prefer to remain in the comfort zone, inert regarding the transformations, in the make-believe of teaching and learning in the relationships between teacher and student, that is, they assume that everything is perfect and there is no need to change.

Faced with our paradigms in the course of work, today our student wants to learn things beyond what is already exposed in the external world, and this requires the teacher to transform new teaching strategies, to enable new horizons of teaching and learning. We hear behind the scenes of our students’ schools that the school “is boring”, and in this perspective the teacher prefers to pretend that everything is fine.

Taking these reflections into account, breaking existing paradigms requires the teacher to be the protagonist of changes from planning to execution.

That said, it is important to emphasize that these changes happen gradually, it is necessary not only for the teacher to get involved in the process, but for everyone to be part of this process as well: the political class, the family, and society in general.

We are all heading towards new paradigms that are already an emergency and no longer a necessity, that is, the change needs to start with us, the teachers, we need to start doing something, unveiling the new, through small attitudes, new teaching methodologies, acting as researchers of new methods that meet expectations.

REFERENCES

ALVES, R. Filosofia da ciência: introdução ao jogo e suas regras. 10. ed. São Paulo, Loyola, 2005.

BEHRENS, M. A. O paradigma emergente e a prática pedagógica. 2. ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2005.

CORTELLA, M. S. Educação, Escola e Docência – Novos Tempos, Novas Atitudes. São Paulo: Cortez, 2014.

DICKMANN, I; DICKMANN, I. Primeiras palavras em Paulo Freire. Passo Fundo: Battistel, 2008.

FOUCAULT, M. Microfísica do Poder. 9. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Graal, 1979.

KUHN, T. S. A estrutura das revoluções científicas. 2. ed. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1978.

KUHN, T. S. A Estrutura das Revoluções Científicas. 12. ed. São Paulo: Perspectiva, 1991.

MORAES, M. C. O paradigma educacional emergente. Campinas: Papirus, 1997.

MORIN, E. Os sete saberes necessários à educação do Futuro. São Paulo: Cortez, 2000.

REVIDE. Cortella faz palestra em colégio de Ribeirão. [S.d.]. Disponível em: https://www.revide.com.br/editorias/gerais/cortella-faz-palestra-em-colegio-de-ribeirao/. Acesso em 10/04/2020.

[1] Master in Teaching Exact Sciences. Pedagogue.

[2] Master’s student in Teaching Exact Sciences. Pedagogue.

[3] Doctor in Electrical Engineering and Master in Mathematics.

Sent: July, 2020.

Approved: August, 2020.