ORIGINAL ARTICLE

LIMA, Élida Valeria da Silva [1], CARIA, Josiano Regis [2]

LIMA, Élida Valeria da Silva. CARIA, Josiano Regis. The chronicle: Training of readers in the 9th year of elementary school. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 05, Ed. 11, Vol. 02, pp. 131-149. November 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/education/the-chronicle

SUMMARY

Reading is the guide axis of teaching in Portuguese and, as such, needs to become a teaching objective, because it is a cognitive, historical, cultural and social process of meaning production. Conceiving reading in this way reminds us of how to organize your teaching. If the senses are not ready in the text, it is necessary to contribute for students to create good strategies to establish relationships necessary for understanding. Such strategies permeate the textual genres and the work planned through them, specifically, the chronicle. The objectives postulated here include knowing these reading strategies for the formation of critical readers of students in a class of 9. year of elementary school in a State School in the municipality of Presidente Figueiredo/AM. The method used is that of mixed exploratory research (quantitative and qualitative) of inductive nature, which led us to the results listed, through the application of questionnaires. The theme, far from being exhausted, deserves to be further discussed and explored, since the formation of critical readers is at the heart of the most discussed issue among specialists and educators of Basic Education.

Keywords: proficient readers, textual genre, chronicle.

1. INTRODUCTION

To understand reading and understand what it is to teach it, is to reflect and talk about it, is to be a reader who feels pleasure in this practice, is to mediate texts and readers. Consequently, the practice of teaching to write in the classroom is seen as one of the most challenging activities for teachers and students, since it is intrinsically linked to reading, being in its distancing its greatest objection. Most teachers say that students have no interest in reading and do not like to read, and the consequence is poor or very difficult writing. On the other hand, many students say that teachers do not have creativity, always propose the same activities, in the same way and in a traditional way in Portuguese language classes, when they inevitably resort to the well-known writing of twenty or thirty lines. The practice of reading in school should start from the teacher’s own experiences, because forming the habit of reading in students is not an easy task. Dialogue must permeate the teaching-learning process around reading and writing, based on real life, so that there is identification, feeling of belonging and protagonism. In this context, the present theme “The chronicle in elementary school” reflects on how pedagogical work with readings of chronicles favors critical awareness and writing skills in students of 9. Year of Elementary School, since the gaps and deficiencies in teaching-learning of reading and writing in this segment of teaching are evident through the dissemination of the results of large-scale evaluations in the State of Amazonas.

Why is students’ little interest in reading literary texts? How to favor, through pedagogical practice, the training of proficient readers? Is writing favored by the habit of reading and especially of the chronic genre? Based on these questions, we aim, in a generic way, to define pedagogical strategies of the teaching-learning process for the formation of critical readers, from the mentioned gender, using it as support for the development of textual production in the school environment. Specifically, the objective is to determine the main difficulties in the formation of readers and producers of opinionated texts of students in the 9th grade of elementary school; define the methods used by Portuguese language teachers, for the development of reading skills with chronic gender; point out, from research, means for the development and strategies of reading, interpreting and writing texts in the teaching work with students of this segment of basic education. The research paper presents the exploratory methodology, with a mixed approach of inductive method. The instrument is the qualitative questionnaire of open questions and questionnaire to students of closed questions, with variables of shows from part of the universe to be researched in a class of 30 students of 9. Year of elementary school and with two teachers in the area of Letters of the Maria Calderaro State School in the municipality of Presidente Figueiredo.

The theme of reading came not only from innovations in the intellectual field, from Brazilian researchers linked to the most recent linguistic studies from other countries, but also from the phenomenon now postulated as the “reading crisis” raising the interest of scholars from various fields, such as Philosophy, Psychology, Sociology, among others, competing for the deepening of studies in the educational sphere. The crisis of reading that we live puts into question the way the school, formal educational institution, has been conducting the process, without gradual changes, without accompanying educational advances in a globalized world in which knowledge is available to all. Thus, it is essential that we turn to the discussions and work postulated here, in order to provide opportunities for the reassessment of the consummate failures and the professional advances of teaching achieved, allowing those who deal with or will deal with the day-to-day classroom, who are able to recognize reading as a conception of life and not of school. This theme was addressed in the interdisciplinary scientific article, Special Edition ABRALIN/SE, Itabaiana/SE, Year VIII, v.17, Jan./jun. 2013, by Cristiane Menezes de Araújo and Sara Rogéria Santos Barbosa.

The Portuguese language area was chosen for this research, which aims to reflect on the issues of reading and writing in Basic Education. School is the space for the exercise of freedom of thought and expression. It is the gateway to reflection on important aspects of human behavior and life in society.

It is in the space of dialogue, of thought together, that learning is ensured. The teacher’s most important role, it should be noted, is not to bring information and knowledge to “pass it on” to students, but to teach them how to deal with the information and knowledge that the world provides them daily. (CAMPOS, 2014, p.21).

It is up to the teacher to create, in the classroom, the conditions for the development of activities that allow each student to dialogue with the text, interrogate it, explore it; Participate as a reader of the privileged text, but without authoritarianism, always receptive to the students’ readings, besides allowing them, as the case may be, access to the interpretations that the work has been receiving over time. In this perspective “to read simultaneously we need to handle with dexterity the decoding skills and to add to the text our previous objectives, ideas and experiences [..]” (SOLÉ, 1998, p. 23).

In the teaching of the Portuguese language, grammar has to be in favor of reading and writing, that is, it must be at the service of language practices, so that students, as they learn the concepts that govern the functioning of the language, become critical and aware of the strategies they have to understand reading and make themselves understood through writing.

2. PCN’S AND TEXTUAL GENRES: BRIEF REFLECTION

The text has long been based on the Teaching of the Portuguese Language in Brazil, whether it is understood as material intended for reading and studying or as something that the student must learn to produce. Around the 1980s, the traditional teaching of school genres par excellence – narration, description and dissertation – textual typology that he attended for years on end (and also attends) the curricular programs of Portuguese in elementary school, is now influenced by notions of textual linguistics.

With the publication of the National Curricular Parameters (PCNs), in 1997 and 1998, a new direction for the teaching of the Portuguese Language emerges. From this document, the situations of production and circulation of texts studied in Portuguese language classes become important and become one of the objectives of teaching the discipline. The texts are everywhere in our society and each of them presents a specificity, as well as an objective. These texts are organized into typologies and genres, which enunciate well-defined social practices.

Every text is organized within a certain genre. The various existing genres, in turn, constitute relatively stable forms of utterance, available in culture, characterized by three elements: thematic content, style and compositional construction. It can also be affirmed that the notion of gender refers to “families” of texts that share some common characteristics, although heterogeneous, as an overview of which the text is articulated, type of communicative support, extension, degree of literaity, for example, existing almost in unlimited number. (BRASIL, MEC/SEF, PCNs 2001, p.26).

It is important to highlight that in the references used by the Parameters, textual typology is not disregarded or abandoned, but incorporated into the study of genres, consisting of typological sequences. The context of gender production and its social function are very important and the focus on language teaching and teaching formal public oral genres is valued. It is from the work with the textual genres in portuguese language classes that students will have an adequate perspective of social demands, so that they become citizens capable of communicating, acting and intervening positively in the situations and resolutions of daily problems of life.

3. THE TEXTUAL GENRES IN THE CLASSROOM AND THE INCENTIVE TO READ

The meaning of reading is not restricted to letters printed on a paper page: astrologers read the stars to predict the future; the musician reads the score to play his instrument; the doctor reads the disease in his patient; The mother reads the need on her baby’s face. Finally, all these ways of reading are associated with the possibility of deciphering, translating signs and reading the world.

The same happens when we read the letters in various media. Reading the name of the bus we will take, from a newspaper or magazine, from e-mail, from a literature book, from a ticket or from a light bill requires different levels of concentration and are driven by diverse interests, arousing also diverse feelings. In addition, there is a diversity among the books we read: there are those who are studying, those that are always being reread, there are the pocket books that we carry to amuse us, the difficult books that we need to almost translate. Different types of books also ask for different readings of each other. In this sense Isabel Solé (1998, p. 93) reminds us that

The objectives of readers with regard to a text can be very varied, and even if we listed them we could never claim that our list would be exhaustive; there will be as many goals as readers, in different situations and moments.

The author cites some examples of reading objectives such as reading to obtain accurate information; read to follow instructions; read to learn, among others. All these examples of “what to read?” remind us of the awareness of the dialogical relationship between reading and teaching this, leading the reader to intrinsic and inseparable social circles of sharing reality. From these statements we can ask: how has reading been practiced in schools and specifically in Portuguese language classes? What are the criteria for the textual choices that the teacher uses in the classroom?

The possibilities of reading in its various textual genres should be expanded beyond the literature books (of consecrated or not authors) and/or didactic. Socially surrounding multimodal texts should be explored so that students become aware of the different languages woven in human communication in different contexts. It is necessary to create situations in which students think about the daily activities that will require them to read effectively, such as searching newspapers for the synopsis of a film on display.

Combining the concepts of textual genre and language practices in didactic referrals certainly produces lasting learning, since it legitimizes the actions of students around the language, that is, it allows them to experience, in the school context, situations of reading, writing and orality similar to those they will certainly face in society, outside the walls of the school. (TAVARES, 2012, p. 67).

It is through interaction and dialogue that the teacher will rethink reading practices at school as a mediator between texts and readers. The mediating teacher also acts as a facilitator of learning and, in the teaching of reading, this is the main stimulator for the habit of reading. Through the active posture in the classroom sharing texts read, informing reviews, reading, explaining and giving examples, exploring reading alternatives, he the teacher-stimulator ends up gaining the pleasure of reading in his students in the foreground and, of course, manages to explore the various genres with his social functions.

Explicit work with textual genres is indispensable in reading classes. In teaching practice, the teacher needs to present to students different genres for them to become familiar with the different ways that texts take to circulate in society. For this reason, performing gender analysis activities is very important to achieve this goal. In addition, the activities give the teacher the opportunity to address two pragmatic elements: intentionality and acceptability […] (OLIVEIRA, 2010, p. 86).

In the work with literary reading in the classroom, one should consider what fits in the reduced fifty minutes of a class or time assigned to it. Hence it is welcome to choose shorter genres – chronicles, short stories, poems – for reading sessions followed by discussions or other activity by the group of students and teacher. For reading books performed outside the school environment, the teacher can determine dates for socialization activities of these readings, through conversations about books, writing reviews, blogs, murals, among others that move the circuits of books in school.

4. THE CHRONICLE: KNOWING GENDER

The word chronic comes from the junction of the Greek term “Khónos” or Latin “Chronos” meaning time. In Portuguese, chronicle has the meaning of brief commentary, published in newspaper, magazine or electronic media. Essentially it deals with real and/or imaginary facts of everyday life, influenced by impressionist and poetic currents.

In the early days of Portuguese civilization, there was the narrative of facts considered important in the political and economic sphere. Later, these records were organized in the so-called Anais of History. In this context, the chronicles also had a strictly historical meaning, since they eternalized the deeds of kings and reported them to posterity. At the end of the Middle Ages, the genre peaked with the accounts of the chronicler Portuguese Fernão Lopes (1418), who described the government of kings D. Pedro I, D. Fernando and D. João I. During the Renaissance the chronicle continued as a historical record text.

The chronicle received the literary contours that we met at the beginning of the 19th century with the advent of Romanticism. The Brazilian chronicle is established at the moment when newspapers began to circulate (from the coming of the royal family) in the main cities.

Although it does not derive from the genres established since antiquity, the chronicle has two historical antecedents: 1) the essay, a type of text created by frenchman Michel de Montaigne in the 16th century, which merges autobiographical experience and reflection on the world with a stylistic stoning that transforms its reading into something comparable to the enjoyment of a novel; 2) the familiar essay of English origin, genre of commentary and personal reverie published in newspapers by so-called “serialists”. (PINTO, 2005, p.9).

The genre was confirmed as being mild, which does not claim to last, since it is exposed, especially in the newspaper, means of communication in which everything is fast and perishable. However, over the years the chronicle has moved away from the mission of informing and commenting, to be aware of and entertain the reader. Language became more stripped down, moving away from argumentative logic and political criticism.

After the Art Week of 1922, with the dissemination of modernist aesthetics and its consolidation, a generation of chroniclers emerged in Brazil, among which we have Manuel Bandeira, Cecília Meireles, Carlos Drummond de Andrade, Rachel de Queiroz, Clarice Lispector among others. The most representative name of the contemporary chronicle, however, is Rubem Braga, who began his career in the 1930s and gave new voice to the Brazilian chronicle. From this,

The chronicle appears as the positive side of our problematic national identity: to a small reality, without reach or possibility of utopia, corresponds to a genre that gives color and form to the oflaws of everyday life, which finds in humor, debauchery and banality a healthy expression of this social informality that, at other times masks economic inequalities, authoritarianism and confusion between the public and private spheres. Ironically, therefore, the chronicle arises from a kind of inferiority complex of Brazilian society and literature, to become an authentically Brazilian genre, with a collection of texts whose riches few literary powers have managed to accumulate. (PINTO, 2005, p.10).

The Brazilian chronicle holds a unique character for its objective style, which transcends its original support due to its lysism. Currently, it is possible to find chronicles of the best writers in Brazil gathered in books and anthologies.

There are chronicles that are dissertations, as in Machado de Assis; others are prose poems, as in Paulo Mendes Campos; others are short stories, as in Nelson Rodrigues; or cases, such as Fernando Sabino; others are evocations, as in Drummond and Rubem Braga; or memories and reflections as in so many. The chronicle has the mobility of appearances and discourses that poetry has – and it is easy that the best poetry is not allowed. (BRASIL/MEC, OLP, 2010).

Because it is a genre that often goes from journalistic to literary, it is diverse, flexible and hybrid, and can use the mask of other genres such as the tale, the dissertation, the memory, or poetry. It is unpretentious and light as an informal conversation between friends, making us see the little details of daily life, as well as the beautiful and great things.

5. READING CHRONICLES AS A TEACHING TOOL, IN THE TRAINING OF READERS OF THE 9th YEAR OF BASIC EDUCATION

Reading and writing, speaking and listening are not exclusive activities of a curricular discipline – that of The Portuguese Language – but of all, since every teacher is a mediator of language. A commitment to be assumed by the school is to enable the student to learn the different texts that circulate socially and, one of them, is the chronicle.

The chronicles deal with reality, daily life, with unpretentious language and simpler themes, usually related to the past and childhood. Because it is a more everyday, confessional, brief and, above all, very closely linked genre to the reality of the reader, chronicles are seen as more fleeting forms than that of novels, short stories and poetry. In classes with students of Basic Education (6th to 9th grade) it is interesting to start the incentive to read through the simplest texts, with known words, with themes close to the student’s universe, to gradually expand the possibilities of reading. Reading is the ability that provides autonomy with regard to understanding the world and the multiple possibilities of interpreting the facts and unveiling, among the multitude of information, with which we are bombarded every day, the values, principles, conceptions that enrich our personal experience. Thus, it is important to put students in contact with the various types of topics addressed in the chronicles, as well as the most literary ones – the chronicles of authors such as Rubem Braga, Fernando Sabino and Carlos Drummond de Andrade. The raw material of the chronic genre are the curious news, common facts of the coexistence between people and that can happen to anyone. These events provide moments of nostalgia, burial or indignation shared by the chronicler and the reader. Through its many facets such as lyrical, humor, essay, descriptive, narrative, dissertation, reflective or metaphysical, this genre presents a singular way that each author sees life, giving it a charming and literary character. Thus, the chronicler’s panorama constitutes a personal dialogue with an object analyzed in a light, short, often objective first-person way, which gives him the personal and hybrid aspect of the chronic genre.

In this conception, Revista Nova Escola addressed the theme entitled “Four reasons to take the chronicle to the classroom”, which we transcribe below.

-

-

- The chronicle narrates events and, therefore, producing this type of text mobilizes some linguistic structures of its own, such as verbs in the past perfect and imperfect and narrative forms in the first person.

- By presenting a short narrative, focused on everyday themes, the chronicles bring a very accessible text from the point of view of reading and written production. That’s why chronicles are an excellent starting point for reading and writing exercises in the classroom, especially from Fundamental 2.

- Through the reading of this literary genre we can initiate students in the articulation of the verbal tenses of the past, verbs of states and transformation. It is important to draw students’ attention to the fact that this textual architecture has a more or less stable form and can be noted in almost all chronicles – which makes it a genre.

- From the point of view of the formation of readers, it is essential to draw the students’ attention to the fact that the chronicles have a look at daily life. (PORTILHO, online)

-

The Brazilian Ministry of Education, in partnership with the Fundação Itaú Social, carries out a biennial and continuous program entitled “Olympiad of the Portuguese Language”. The objective is to contribute to the improvement of the reading and writing of students from public schools throughout the country, through the didactic sequences directed to certain textual genres, in the case of 9. Year of Elementary School and 1. High school grade, the chronicle. The program involves not only teachers and students giving them all the pedagogical support necessary to execute the project, but also local, municipal and state educational managers. In odd years, MEC/CEMPEC serve these managers and technicians from the Departments of Education who act as trainers, principals, teachers and, in even years, promote a text production contest for students of 5. and 9. Years of elementary school. This is an important opportunity for teachers and students to improve reading and writing, using in one of the teaching stages, the chronic gender, the object of our present study.

6. METHODOLOGY

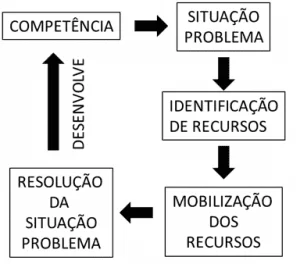

The knowledge discovered through research can be applied to many daily and professional activities, whether in problem solving, in the concerns resulting from practical practice, interpersonal coexistence, in the formation of opinions or in many others.

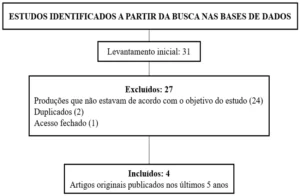

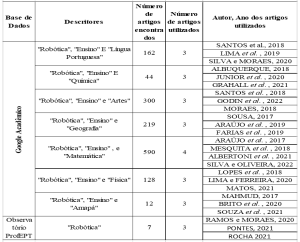

The research methodology allows, among others, the reach of answers to the questions and hypotheses formulated. The method and techniques present some items of the research that we will specify, such as the nature, purpose, approach to the problem, objectives and technical procedures used to achieve the results.

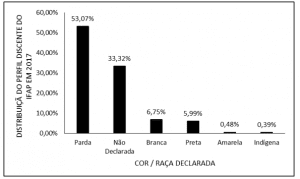

The nature of this research is applied/exploratory, which aims to generate knowledge for practical application through proximity to the problem, in this specific case, the classroom, starting from theoretical studies on the proposed theme and advancing to the procedures of data collection on site. The objective is based on the achievement of answers for the better learning of students in the 9th grade of elementary school and the consequent definition of pedagogical strategies in the teaching-learning process, with a view to the problem, training of critical readers. This purpose points to the achievement of the specific objectives of the present research, synthesized by the verbs determine (the main difficulties), define (strategies used by teachers in the teaching of reading) and point out ways to improve the praxis of teaching. The approach to the problem will be taken by means of inductive method (part of the private data for the general) mixed, being a quantitative questionnaire closed (5 questions) to students from a single class of approximately 35 adolescents and open questionnaire (6 questions) applied to two teachers in the area of letters. Thus, technical procedures permeate the bibliographic research and data collection.

7. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The presentation and discussion of the results consist of the analytical interpretation of the data obtained, based on the identified problem, the theorists studied and the proposed objectives. This research presents the exploratory methodology, with mixed inductive approach, objective questionnaire closed to students (29) and qualitative aimed at two teachers. The first analysis refers to the quantitative approach of closed questionnaire with five questions to the students. For this, we present the questionnaire in full and, then, the tabulation of the data by answers and their respective commented graphs.

7.1 ANALYSIS OF THE RESULTS OF THE FIRST PART OF THE SURVEY – QUESTIONNAIRE CLOSED TO STUDENTS

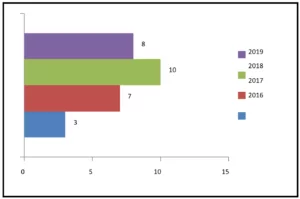

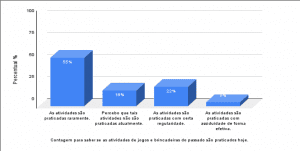

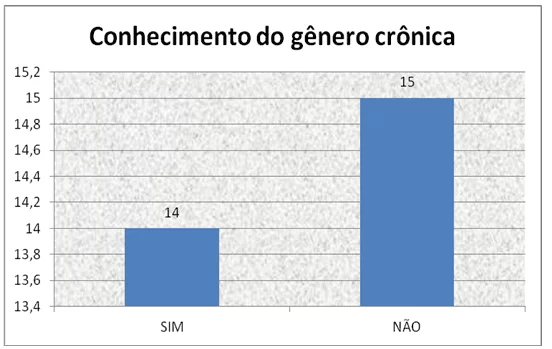

Graph 1 – Knowledge of the chronic genus

The question one aims to know if the students affirm or deny the very concept of a chronicle, that is, the structure of the gender that allowed them to identify it as a chronicle. Of the twenty-nine students surveyed fourteen (14) stated that yes and fifteen (15) stated that no. This evidences that gender is little explored in the classroom or if it is presented to students there is no mention of the textual structure worked.

Isabel Solé (1998), states that when we read we have varied objectives and, these should be defined the moment we come into contact with the text. If the teacher opportunistizes the anticipation of the text, exploring its characteristics as a genre, the reader previously formulates his goal of reading, regardless of the pedagogical purpose, whether to verify what he learned, practice reading aloud or just read for pleasure, among others.

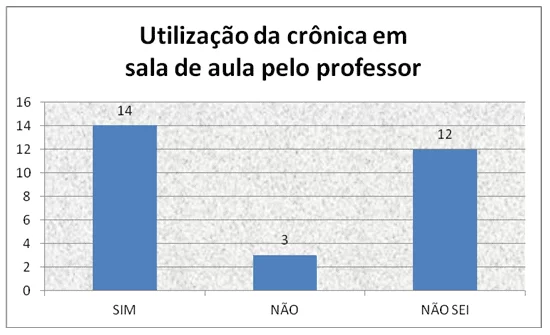

Graph 2 – Use of the chronicle in the classroom by the teacher

In questioning two, exactly fourteen students stated that their Portuguese-speaking teacher has already presented the chronic genre in the classroom. Comparing this specific data with the variant (yes) of question one, we observed that there is coherence between the answers, since exactly fourteen students conceptualize chronic. Analyzing the answers we assume that this portion of the class of 48.2% is fully aware of the gender and its use by the teacher.

The other answers of this item show that: twelve students, that is, 41.3% of them, are not aware of the textual genre worked in portuguese language classes; three students (10.3%) state that the teacher has not yet used the chronicle in the classes. The answers lead us to reflect on the pleasure of reading transmitted by the teacher to the students. In this context, “(…) it would be necessary to distinguish situations in which reading is worked and situations in which it is simply read” (SOLÈ, 1998, p. 90).

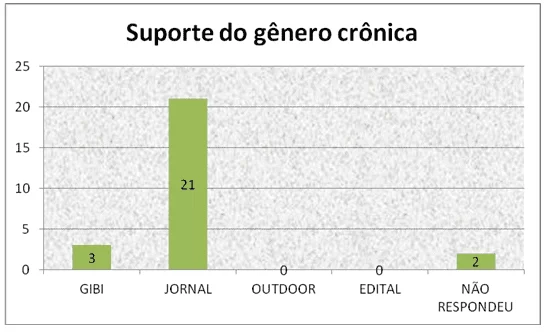

Graph 3 – Chronic gender support

In questioning three we approach the support of the chronicle. This approach leads us to the social use of the text and its vehicle of expression. Of the twenty-nine participants in the survey, 74.4%, exactly twenty-one students, recognize this use. Two of the students did not answer and three of them, 10.3%, pointed to the comic as support for a chronicle. Most students are aware that a chronic text could not be conveyed on billboard, edict or comic book. The PCN’s in volume 2, p. 23 of Portuguese language, point out that

The mastery of language has a close relationship with the possibility of full social participation, because it is through it that man communicates, has access to information, expresses and defends points of view, shares and builds worldview, produces knowledge.

The recognition of the support of a given textual genre, in this case the chronic, evidences knowledge of the world on the part of the students, not limited to factual or specific concepts.

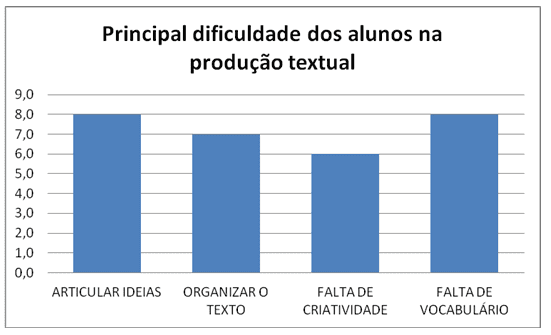

Graph 4 – Main difficulty of students in textual production

In the fourth question, the variants articulate ideas (27.5%), lack of creativity (20.6%) and lack of vocabulary (27.5%) evidence deficiencies in the regularity of reading on the part of students, since the formation of a reader is neither a spontaneous or natural process. Reading is closely linked to writing and, to understand the many meanings of the text, in addition to participating in a community of readers, in this case the school, it is necessary to have contact with more experienced readers.

On the other hand, 24.13% answered that their main difficulty in producing texts refers to their structural organization. This portion of the students presents, by the answers listed, gaps in the practice of writing, which is indirectly, a consequence of the lack of readerregularity.

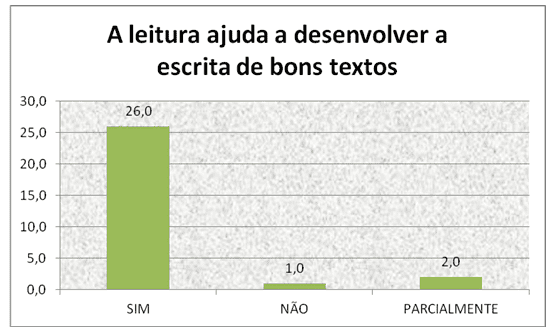

Graph 5 – Reading helps develop the writing of good texts

A large portion of the twenty-nine students surveyed (89.6%) agrees with the statement that reading is the guide axis of teaching-learning and contributes significantly to cognitive development (ideas reasoning, creativity, criticality), as well as to the development in the writing of texts and, consequently, to the effective exercise of citizenship. According to the PCN’s (v. 2 p. 53) competent reader is the one who

performs an active work of constructing meanings of the text, based on its objectives, of its knowledge on the subject, about the author, of everything that is known about the language: characteristics of gender, of the carrier, of the writing system, etc.

The other answers, NO (3.4%) and PARTIALLY (6.8%) evidence that these students have not yet been aware of the importance of reading for success in any area of life.

7.2 SECOND PART OF THE RESEARCH: QUALITATIVE ASPECT

The qualitative questionnaire was applied to two teachers who were formed in Letters, both professors of the Maria Calderaro State School in Presidente Figueiredo-AM, working for more than five years in Elementary School 2. Next, we will list the answers given and discuss the results in the light of the theoretical basis presented in this work.

7.2.1 Analysis of open questionnaire responses

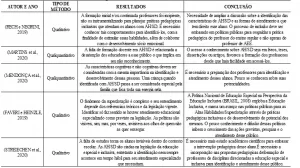

Table 1 – Questionnaire open to teachers

| Variants | TEACHER 1 | TEACHER 2 |

| 1. Use of chronic in classes | I use it sometimes. | I use it once in a while. |

| 2. Characteristics of the chronicle | Short narration; humor, irony, criticality and satire; colloquialism; everyday facts. | Short text of long-fetched language. It can have humor, satire and irony. Day-to-day facts. Orality. |

| 3. Commentary on the quote: “The chronicle is a kind of magnifying glass that you put in a subject.” (PRATA, 2015). Agree? Justify. | Yes, because in every narrative you expose has everyday everyday facts and fit perfectly into the context of the chronicle. | Yes, in a way because it is a reading that involves the reader, since the person approaches the author as if he were in an informal conversation. The chronicler tends to dialogue about intimate facts with the reader. |

| 4. Chronicle: literary genre? | Yes. | Yes. |

| 5. Is the chronicle an interesting genre to favor the habit of reading? | Yes, because it is a short narrative, it does not become tiresome and boring. | Certainly, for being a short text of simple language, pleasurable for all age groups. Also for being satirical, ironic, where the characters express feelings. |

| 6. Point out the greatest difficulty encountered by you in the work with the reading and textual production of students of the 9th year of elementary school. | Students don’t like reading indicated readings, books. The library often does not have books to attract the clientele, who like adventure and a lot of excitement. | It is the total disinterest of the students, especially when they reach the 9. Year, because they think they don’t need reading anymore. Unfortunately that’s our reality. |

Source: Prepared by the author, year 2015.

When analyzing the answers in table 1, it is observed that both teacher 1 and teacher 2 dominate the knowledge of the chronic textual genre, recognizing its consecration in Brazilian literature, as well as agreeing opinionatedly that the chronicle would be an interesting genre to stimulate reading in the classroom. However, both only use gender in the classroom sporadically, which corroborates that 51.6% of students do not recognize it when it is being used by the teacher, as shown in graph 2 of the closed questionnaire directed to students.

When invited to comment on the quote from Prata, 2015 on the chronicle as a kind of magnifying glass to the subject, only teacher 2 briefly signaled the details of the daily life that the chronicle offers to the reader. In item 6 of table 1, we observed that the difficulty of reading among the students, in the teachers’ view, is the lack of interest in reading. This result leads us to the answers listed in graph 4 of the closed questionnaire, in which 75.6% of the students looked at options for answers to writing difficulties related to the lack of the habit of reading, such as lack of creativity to develop a theme and articulation of ideas on paper. In this sense, the teacher’s performance is essential in the formation of critical readers, according to Oliveira (2010, p.71),

The mediating function that the teacher has in the development of the reading competence of the students is very important. As a mediator, the teacher is given the task of helping his students master reading strategies that are useful to them in the acts of textual interpretation. These strategies are procedural actions closely linked to the students’ previous knowledge, which need to be addressed in the classroom.

Among the competences and skills that can help an adolescent to become a critical citizen stands out the reading competence and the training of writers, because the possibility of producing effective texts has its origin, in the practice of reading, space for the construction of intertextuality and source of guide references.

8. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

When we talk about reading in school, teaching and learning to read, we are thinking about the type of reading involved in this process. This comes the subjective investment in the reader and in the appreciation of their choices. When we speak of the chronic genre, of the chronic text, we speak and think much more than a tangle of words, phrases, or literary conjectures; we speak of pulsating life expressed in words. By the chronicle, we are faced with the experiences of the common man, expressed in ordinary language and published regularly in the pages of the press, that is, in the creative movements of public life that are, in the first instance, newspapers and magazines. Many renowned authors have dedicated themselves to writing chronicles, such as Luis Fernando Veríssimo, Lourenço Diaféria, Domingos Pellegrini, making it a contemporary genre by renewing repertoires and making it fruitful to teaching and encouraging reading in the classroom. This work allowed the redefinition of gender as of paramount importance in the teaching work to encourage reading and, consequently, in the formation of critical readers. It also made possible the definition of methods and knowledge of the pedagogical practice of two professionals in the area of Letters in Elementary School in the researched school. We determined the main difficulties encountered in working with the chronic genre in order to train critical readers. We know the look, directed to this literary genre, of some of the adolescent students of the 9. year of elementary school. These objectives were achieved, but the theme was not and could not be exhausted, because we concluded that the chronicle was being little explored in the classroom. Hence the suggestion to continue with the theme of the research, focusing on didactic strategies so that the chronicle is better known and used as a strategic text in the formation of the critical reader, since it allows total freedom, in the sense of creating and perpassing varied genres, including the opinionated. The difficulties in conducting the research were minimal and there were virtually no negative points. There was acceptance by parties of the people involved for all the work performed.

REFERENCES

BRASIL.MEC. Olimpíada de Língua Portuguesa. A ocasião faz o escritor: caderno do professor. São Paulo: CENPEC, 2010.

BRASIL. SEF/MEC. Parâmetros curriculares nacionais: língua portuguesa. V. 2. Brasília, 2001.

CAMPOS, Elísia Paixão de. Por um novo ensino de gramática: orientações didáticas e sugestões de atividades. Goiânia: Cânone Editorial, 2014.

OLIVEIRA, Luciano Amaral. Coisas que todo professor de português precisa saber: a teoria na prática. São Paulo: Parábola Editoral, 2010.

PORTILHO, Gabriela. Leve a crônica para as aulas de Língua Portuguesa. Nova Escola versão eletrônica disponível em <http://revistaescola.abril.com.br/ fundamental-2/leve-cronica-aulas-lingua-portuguesa-730805.shtml?page=2>

PINTO, Manuel da Costa (Org.) Crônica Brasileira Contemporânea (Antologia). 1. ed. São Paulo: Moderna, 2005.

SOLÉ, Isabel. Estratégias de Leitura. Tradução Cláudia Schilling. 6. ed. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 1998.

TAVARES, Cristiane et. al. Guia Nós da Sala de Aula. (vários autores) Organização Heloisa Ramos. 1 ed. São Paulo: Ática, 2012.

[1] Postgraduate Specialist in Psychopedagogy; Postgraduate Specialist in Integrative Management; Graduated in Higher Normal; Graduated in Brazilian Literature Letters; Training at medium level in 2nd degree professionalizing in Magisterium.

[2] Advisor. PhD in progress in Humanities and Arts. Professional Master’s degree in Education and Science Teaching. Specialization in Informatics and Education. Graduation in Degree in Letters- Vernacular.

Sent: March, 2020.

Approved: November, 2020.