ORIGINAL ARTICLE

SIQUEIRA, Leni Porto Costa [1]

SIQUEIRA, Leni Porto Costa. Pedagogical Practices In the Context of Inclusive Education: Literacy Based on The Trunk Method And Del Cerro For Students With Down Syndrome. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 06, Ed. 03, Vol. 07, pp. 75-99. March 2021. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/education/context-of-inclusive-education, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/education/context-of-inclusive-education

ABSTRACT

This article is a descriptive study, with a qualitative approach, with the report of the literacy process of a student with Down Syndrome (DS), having as guiding principle the contributions of the Perceptual-discriminative Learning method developed by Troncoso and del Cerro (2004), which exemplify the global method to literate people with DS, using personalized teaching materials directed to the specificities and interests of the student. In this perspective, we present the case study, with the experience of literacy, in the inclusive context, of a student with DS, carried out in a public school in the city of Niterói. Data were collected through direct observation in school activities, extracurricular activities and the student’s relationship with his peers, through interviews with parents and research in the student’s school record. The results showed that the use of structured and personalized materials, based on reading and writing work for people with DS developed by Troncoso and del Cerro (2004), contributes to develop literacy skills, despite the learning difficulties involved in the syndrome.

Keywords: Down Syndrome, Literacy, Inclusive Education, Perceptual-discriminative Learning Method.

1. INTRODUCTION

Being a teacher in the scenario of inclusive education requires flexibility, constant learning, welcoming the other with its limitations and potentialities. It also implies dealing with diverse and adverse situations, constantly seeking strategies that favor students’ learning. Because to teach information transmission is not enough, the important thing is “to discover what is meaningful learning for students, because they will be interested in what, in some way, directly affects them (GASPARIN, 2001, p.8).

In this context, we have the student with DS who presents learning delays (CHAPMAN; HESKETH, 2000), requiring teaching to go out of the traditional and follow another path, with flexible and dynamic proposals (ABBEDUTO; WARREN, CONNERS, 2007) and that also needs to develop learning together with their peers, learning and playing together (TILSTONE; FLORIAN; ROSE, 2000).

On this, Tilstone and Florian (2000) state that children should not be “excluded or sent to another location due to their disability or learning difficulties and there are no legitimate reasons to separate children during the period of their schooling.” (TILSTONE; FLORIAN; ROSE, 2000, p.123).

Attendance at regular school is of fundamental importance for the development of students with DS, but in a way that there is their involvement with all of the class, with access to teaching that integrates and provides their cognitive development (CORREIA, 2003).

DS is a genetic anomaly, also known as trisomy 21, caused by a chromosomal alteration. About 95% of cases are characterized by a simple trisomy (an extra chromosome) and 5% can be characterized by a translocation, that is, the additional chromosome 21 is fused to another autosomor a mosaic, which are trisomal cells next to normal cells (SCHWARTZMAN, 2003; KOLGECI et al., 2013).

Among the common characteristics of people with DS, we can highlight deficit of psychomotor, intellectual development, weight-height and facial dysmorphia. They may also present endocrine-metabolic alterations, mainly involving the thyroid gland, congenital heart diseases and changes in sleep patterns (BRASIL, 2013).

In the operational memory (temporary storage and manipulation of information), they present deficits in their verbal component (phonological loop, responsible for the temporary storage of verbal information), requiring specific and more intensified stimulation for effective development. However, in spatial vision skills they are relatively preserved (CARRETTI; LANFRANCHI, 2010; LIMA FREIRE; DUARTE, HAZIN, 2012).

Although people with DS present the cognitive impairments in question, learning reading and writing is crucial for them to have independence in their activities, to be able to accomplish the small things of everyday life such as going to commerce, using public transport and independently solving future everyday issues (BUCKLEY; BIRD, 1993).

When the teaching programs are adapted to the interests and needs of people with DS, respecting their specificities, limitations and potentialities, their maturity and interests they will feel safe and will be able to learn better (TRONCOSO; DEL CERRO, 2004).

To exemplify the work in this perspective, we will present the case study of the literacy experience, in the inclusive context, of a student with DS, carried out in a public school in the city of Niterói. In order for the literacy process to be successful, it was necessary to establish a systematic and structured program in order to ensure that the student could develop his/her attention, observation, perception and discrimination skills.

In this perspective, we use the contributions of the work developed by Troncoso and del Cerro (2004), which exemplify the learning and cognitive development of people with DS, from the elaboration of personalized teaching materials and directed to the specificities and interests of the student.

2. THE PERCEPTUAL-DISCRIMINATIVE LEARNING METHOD OF TRONCOSO AND DEL CERRO

The Perceptual-discriminative Learning Method, developed by Troncoso and del Cerro (2004) began in 1970, being applied to the teaching of reading and writing in students with learning difficulties, some had intellectual disabilities as well as other perspective and sensory difficulties.

The method is part of the global reading and not of the parts, because for the authors, the letters and syllables do not carry meaning and to read is to understand, it is to perceive meaning. “Since we are babies, what comes to us are words and not letters or syllables” (TRONCOSO; DEL CERRO, 2004, p. 48). They also note that the student with DS has the visual and perceptual ability to “globally capture the set of written signs that make up a word, without having to divide it first in its letters and syllables” (TRONCOSO; DEL CERRO, 2004, p.13).

According to the authors, it is important to invest in the potential of the person with DS and explore the areas where they have more ease of learning as is the case of visual memory, offsetting the hearing difficulties present in the syndrome (TRONCOSO; DEL CERRO, 2004).

People with DS have visual attention, perception and memory as strengths and develop with systematic and well-structured work. However, there are important difficulties in auditory perception and memory, which are often aggravated by acute or chronic hearing problems. For this reason, the use of learning methods that have strong support in verbal information, in hearing and interpretation of sounds, words and phrases is not very effective. (TRONCOSO; DEL CERRO 2004, p. 70).

Pennington et al. (2003) also corroborate this statement when they report that, although students with DS present a delay in the development of cognitive functions, they do relatively well in spatial and visual memory tasks (PENNINGTON et al., 2003).

In order to have good results in the application of the method it is necessary that the student is motivated and that the subjects and materials meet their interests and abilities, in addition, success will occur if the work is carried out “[…] without haste and without pauses, if the program is not abandoned early and if appropriate adaptations to the teaching-learning process are introduced.” (TRONCOSO; DEL CERRO, 2004, p. 67).

In addition, the focus on teaching should encompass the development of autonomy, responsibility, maturity so that there is effective inclusion of children with DS in school and in the social and cultural sphere (TRONCOSO; DEL CERRO, 2004).

Troncoso and del Cerro (2004) divided the Perceptual-discriminative Learning method into stages: three stages for Reading and three for Writing. In sure that the student does not lose interest in learning it should be noted that “the three stages are interrelated and sometimes the objectives of each must be worked on simultaneously. The fundamental reason for this process is due to the fact that the conditions of understanding, fluency and motivation should be maintained and consolidated at all times of the process” (TRONCOSO; DEL CERRO, 2004, p. 73). However, it is important not to advance to the next phase if the student is not safe and properly assimilated to the previous phase (TRONCOSO; DEL CERRO, 2004).

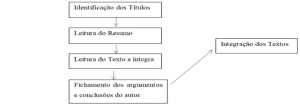

We elaborated a synthesis of the three stages of the Perceptual-discriminative Learning method that comprise reading teaching and the three stages of Writing, as we will see below.

Phases of Reading: a) Global perception and recognition of written words – comprises the recognition of the written word and its meaning, starting from the word to the sentence; b) Learning of syllables – we work with the identification and recognition of the sylabic division so that the student can advance in reading other words. The important thing is that the child “understands that there is a code that allows us to access any written word not learned previously” (TRONCOSO; DEL CERRO, 2004, p. 73); c) Progression of reading – constitutes the apex of reading learning where students can already read more complex texts productively and effectively.

Writing Phases: a) Early stimulation – development of perceptual and motor capacity through the stimulation of dashed to favor the performance of spelling. b) Second stage of the writing method – the goal is for the child to draw the letters and make the sylabic formation to then form the words and then the sentences. For Troncoso and del Cerro (2004), the aim is “to make the student be able to trace all the letters of the alphabet, be able to join the letters forming syllables and words and write the first sentences” (TRONCOSO; DEL CERRO, 2004, p. 182); c) Progression in writing – In this last phase the main objective for the authors “is to make the student usually use handwritten writing for the activities of daily living, to solve situations that require writing and to communicate with others” (TRONCOSO; DEL CERRO, 2004, p. 198).

For the authors, the mastery of writing for children with DS is more complex than reading due to difficulties in motor coordination, anatomy of the hand, lassidation of ligaments among other factors present in the syndrome and that influence their effective performance in this area. (TRONCOSO; DEL CERRO, 2004).

In this study, the main focus was on exploring the reading stages, because we observed the need for a more intense and prolonged work of fine motor coordination with the student with DS, due to the difficulties evidenced in this area. The activities surrounding writing were very demotivating, the student got tired easily and gave up continuing the tasks. Therefore, all the activities initially developed he went through games, collages in the notebook and manipulation of chips with words, syllables and letters of the alphabet, respectively.

Troncoso and del Cerro (2004) state that the person with DS presents insufficiency in the development of the prefrontal cortex, this fact brings difficulties for deductive reasoning. Due to the damage resulting in the prefrontal cortex, the teacher should devote his attention to intuitive learning, since in the course of learning the person with DS will learn to divide the words into syllables and letters, until he understands the process of joining letters and the composition of words (TRONCOSO; DEL CERRO, 2004).

In this context, education should have:

[…] a more systematized methodology, with more installment objectives, with smaller intermediate steps, with a greater variety of materials and activities, with a simpler, clearer and more concrete language, putting more care and emphasis on the motivating and interesting aspects. (TRONCOSO; DEL CERRO, 2004, p. 19).

Thus it is clear to understand that, for the person with DS to learn to read, the path from letters to syllables and these to words is very difficult and disstimulating, being easier to hold their attention in a simple word with meaning than in a sign unintelligible to it. (TRONCOSO; DEL CERRO, 2004).

The main features of the method are:

a) Adjust to the cognitive abilities of the child with DS. (b) take into account the characteristics of each child. c) Stimulate and facilitate subsequent cognitive development: short- and long-term memory exercise, personal autonomy in the acquisition of concepts and the ability to correlation. d) Facilitate the development of expressive language. (TRONCOSO; DEL CERRO, 2004, p. 15)

The authors also emphasize the need to work with the child some important concepts such as association, selection, classification, appointment and generalization, because, “A good discriminative learning program allows the child to develop the organization and mental order, logical thinking, observation and understanding of the environment that surrounds it. (TRONCOSO; DEL CERRO, 2004, p. 37).

The method also has as a guiding principle the presentation of a vocabulary that children understand and are familiar with, using pictograms and the word written on cards of 15 × 10 cm (TRONCOSO; DEL CERRO, 2004).

3. GOALS

- GENERAL: Present the literacy process of a student with Down syndrome, based on the studies of Troncoso and del Cerro (2004) on the Perceptual-Discriminative Learning Method.

- SPECIFIC: a) Present the approach of the Perceptual-discriminative Learning Method, developed by Troncoso and del Cerro (2004), for the learning of people with Down syndrome; b) Identify the stages of the literacy process in the inclusive context of a student with Down Syndrome, based on the Perceptual-Discriminative Learning Method of Troncoso and del Cerro (2004); c) Demonstrate the materials and games elaborated and used to support the literacy of students with Down Syndrome;

4. METHODE

The study is based on qualitative research, descriptive in nature, with a case study, based on the observation and monitoring of the learning development of a student with Down syndrome.

It was based on the literacy method proposed by Troncoso and del Cerro (2004) for children with Down Syndrome.

4.1 SEARCH SITE

The study was carried out in a school in the municipal network of Niterói, which serves students of early childhood education and elementary school I, located in an upper middle class neighborhood, dominated almost exclusively by single family residences and of high constructive standard. However, its clientele is predominantly from the favelas located around it.

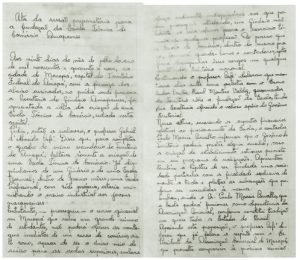

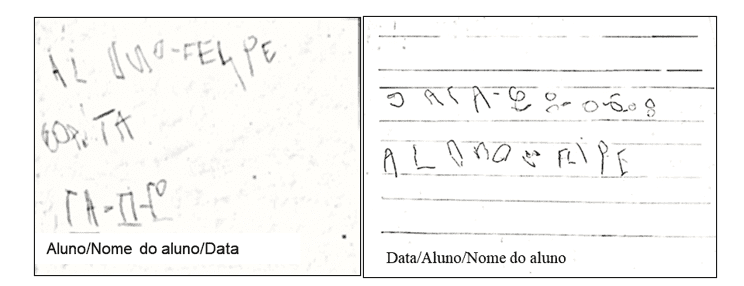

4.2 PARTICIPANT

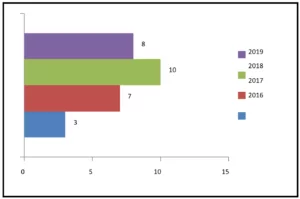

Frederico[2], student with Down Syndrome, 11 years old, attending the 3rd year of elementary school, in the regular class. He presented impaired communication and almost unintelligible speech, needing to make gestures so that people could understand him. He was aware of the letters of the alphabet, but did not understand the process of forming the word from the junction of the letters into syllables. He wrote incorrectly and with great difficulty only the first name, presenting important difficulty of fine motor coordination and his spelling was very light and irregular, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 – Copy using support form: STUDENT (student name next).

4.3 DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS PROCEDURES

The study began with a request for consent to the family and with the signature by the student’s mother of the Free and Informed Consent Form to perform and disseminate it. An interview was also conducted with the parents to obtain more information about the student, his preferences and difficulties in daily activities in the family context.

The contact with Frederico was based on teaching practice in a municipal school, where the researcher can participate directly in the school routine, because it is part of the context as a pedagogical support teacher of the school. The observation was made in the most natural way possible: in the classroom, in the playground, in the cafeteria, in tours, visits and experiences of Frederico with his classmates, in addition to meetings with the pedagogical team of the school, for discussion about the student’s development. And the whole process of observation and teaching practice with the student was recorded in the form of notes, in a field diary.

In addition, a research was carried out in the student’s form, through the Individual Reports prepared by the teachers, to identify the processes of development and learning and to understand the level of knowledge that he was.

Data were collected from 11 months, Monday to Friday, during school hours, in the morning, from 7:30 a.m. to 12:30 p.m.

A qualitative analysis was performed using as theoretical basis the perceptual-discriminative learning method proposed by Troncoso and del Cerro (2004) for literacy of children with DS.

5. THE LITERACY PROCESS BASED ON PERCEPTUAL-DISCRIMINATIVE LEARNING METHOD

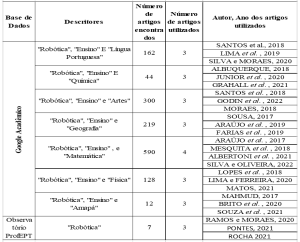

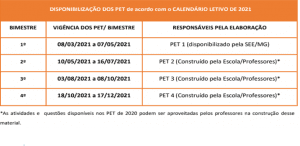

Before starting the application of the method of learning reading and writing of Troncoso and del Cerro (2004), as mentioned earlier, we made a survey in the student’s school record to ascertain the level of knowledge, its difficulties and potentialities, from the eyes of pedagogical support teachers who worked with Frederico in the 2nd and 3rd years of elementary school , and prepare Table 1 based on the information found in the reports made by these teachers.

Table 1 – Report on Student Development in the 2nd and 3rd Years of Elementary School

| DEVELOPMENT ASSESSMENT SHEET |

| Portuguese Language |

| Recognizes only the first name, but cannot write it or copy it correctly with the plug backing;

Recognizes all vowels and consonants of the alphabet, except W, Y, and K; His oral language is greatly impaired, presenting difficulties to communicate; It does not formulate complete sentences, possessing mono-sylabic vocabulary; It does not articulate the words correctly; Does not participate in oral communication activities; It shows no interest in reading; Does not carry out writing activities; He cannot identify orally parts of the text, having difficulties in saying the logical sequence of the facts (beginning, middle and end); Cannot perform actions from the reading of instructions made by the teacher; It cannot analyze and interpret texts with engravings only, that is, non-verbal; It does not express thought in an organized way; She has difficulty in representing through drawings the stories read by the teacher; She has difficulty keeping her attention when the teacher reads in the storybooks in general.

|

| mathematics |

| Recognizes most colors;

It does not identify geometric shapes; It makes no relation between the quantity and the numeral; It only recognizes the numerals correctly up to number five, identifies some up to number 10 and has insecurity and confusion in the recognition of others; He has difficulty identifying the ordinal numbers: the third and last of the queue, for example; It cannot perform mathematical activities such as simple addition and subtraction, numeral activities with predecessor and successor, the largest numeral and the smallest among others; You don’t know the ballots in our monetary system; |

| Visual perception / Motor Coordination |

| It has delay in fine and thick motor coordination;

He has a lot of difficulty in writing, has no firmness and does not know how to take the pencil correctly with both fingers; He has difficulties in fine motor skills such as pinching things, tearing paper with his fingers, picking up small objects with his fingertips; Does not draw with defined shapes; It cannot respect the boundaries of the sheet and drawing; It has difficulties in performing clipping, gluing and painting activities; Difficulties to recognize: outside/inside, up/down, far/near; behind/in front, left/right; Difficulties in grouping elements by their characteristics I don’t copy words written on the board by the teacher alone.

|

| Autonomy and participation in school/extracurricular activities |

| The student is very dependent, always needing support to perform tasks and activities;

You need to develop the autonomy: you do not take or keep the materials in the backpack; does not feed or perform personal hygiene alone; It is not participatory in classes and does not interact with colleagues in the proposed activities; He has difficulty doing group activities. He does not participate in cultural activities with colleagues, such as dance, plays, science fair, among others.

|

Source: Information obtained from the student’s form – abstract prepared by the researcher.

In order to better evaluate Frederico’s difficulties and potentialities, in addition to the data collected and presented in Chart 1, direct observation and activities were performed with the student in the school context and interviews with parents. As a result of this survey, the first point that caught the student’s attention was the lack of autonomy and their dependence on an adult to assist him/her in activities of daily living.

According to the authors, one of the focuses of teaching with children with DS should be the development of autonomy, seeking to provide strategies to boost responsibility and maturity, so that they acquire skills that facilitate inclusion with the other children of their social group (TRONCOSO; DEL CERRO, 2004).

Therefore, the first phase of the study was to work strategies with the student for the acquisition and development of autonomy, such as letting him serve himself in the cafeteria at lunchtime and eating without the help of an adult; teach you how to use the bathroom: go to the bathroom alone, flush, clean yourself, wash your hands; do oral hygiene: pick up and store the toothbrush and toothpaste in the backpack, put the paste on the brush and brush the teeth; to make it possible for him to circulate alone around the school giving assignments such as picking up some material in the secretariat, in the reading room, among others.

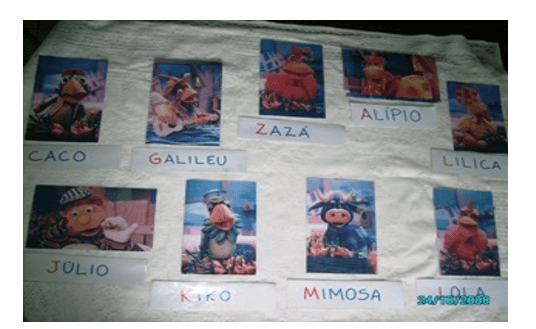

Following the indications of Troncoso and del Cerro (2004) who says that for the teaching of reading the teacher should use attractive materials, varied and adapted to the interests of the student, I noticed a curious fact in the behavior of Frederico that was his fascination with the DVD of the “Turma do Cocoricó”[3] and, for this reason, every day he spent hours in front of the television (at school and at home) watching the episodes and stories of this class. It was an obsession that bothered parents, but used by the school as a resource to keep the student quiet and entertained. However, because of this, he knew the names of all the characters, the songs and even the puppet lines and movements in the successive stories.

Therefore, I tried to start the process of teaching reading by exploring the student’s interest in the names of the characters of the Turma do Cocoricó and then, following the instructions of the method, I presented other words formed by simple syllables, as we will see below.

I provided the images of all the characters of the Turma do Cocoricó and their respective names. I printed and plasticized, separately, the names and photos to get the student’s attention and thus start the process of literacy/reading acquisition, as illustrated below.

Figure 2 – Turma do Cocoricó’s Characters

I presented the material to the student as if it were a guessing game and proposed the joke as follows: as I showed a character, I asked their name. When the student said the character’s name, I would place below the character figure the token with their respective name and continued to ask. In the end, when all the characters were named I would remove the tokens with the names and propose that the student put them back in the correct places.

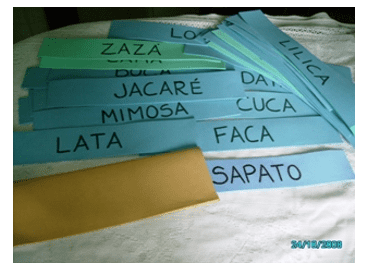

Following the guidelines of the Perceptual-discriminative Learning method, I prepared the “Chip Game” (Fig.3) to increase the student’s repertoire of words. I used several tokens with images of objects and animals and then the word corresponding to the image. The authors advise that the images must be clear and the child must understand and know their meaning, and then associate the graphic symbols with the image and then the word alone, to see if he can remember it (TROCOSO; DEL CERRO, 2004).

This game was prepared shortly after the positive result with the chips of the names of the Turma do Cocoricó. The figure was initially presented and then we talked about what it meant to the student. Then the figure and the name, and then the plug only with the name. After the student handled all the forms I removed the figures that contained the names, shuffled and asked Frederick to put below the corresponding name.

Figure 3 – Chip Game

For the authors, the child has to be motivated and, for this, one must seek words that are of a theme of interest to them. Thus, from the interests of the student, other words were inserted and the discovery took place.

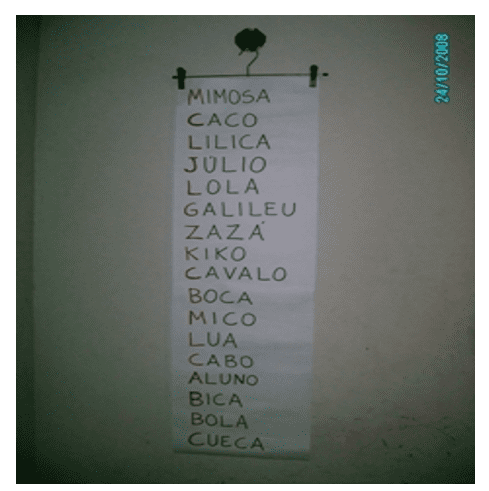

The words Frederico was discovering and learning were placed in the “word bank” (Fig. 4) and fixed to the wall, next to the student, so that he could consult them whenever he wished with ease. The word bank was made of strips of paper 40 kg, 1.20m x 0.30m. In them I wrote the words that the student already recognized and the new ones he was learning and hung on the wall with a clothes hanger.

Figure 4 – Word Bank

When the number of words increased, I elaborated the alphabet, which initially had 144 words that the student already knew how to read.

Figure 5 – Alphabetary with 144 words.

The alphabet was composed of figure-word-meaning. After the student could already read and write the word, it was placed below it, which it meant to him.

According to Troncoso e del Cerro (2004), it is recommended to teach the syllables after the student has seized, in the previous stage, about 200 words. Thus, several activities were carried out with Frederico, from the recognition of the syllables, with the objective of consolidating and developing learning, the construction of writing and reading and stimulating the student’s memory, considering that he already knew how to read more than 300 words at this stage. Below, we list some of these activities.

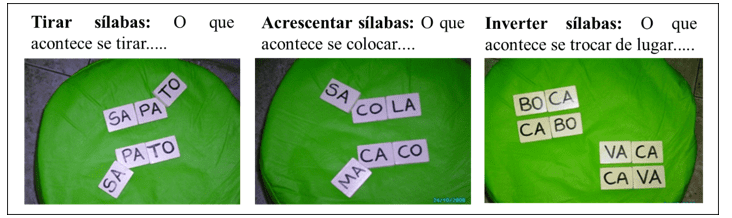

5.1 SYLLABIC MANIPULATION GAMES

Figure 6 – Syllabic manipulation

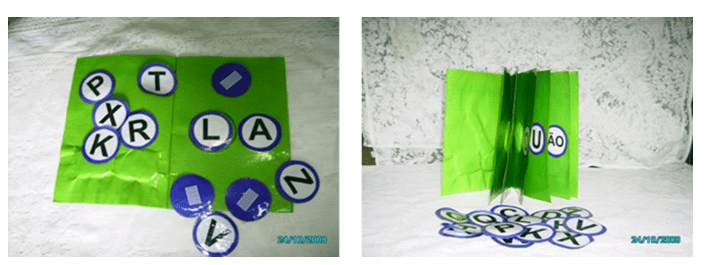

5.2. BUILDING WORDS WITH SYLLABIC TOKENS

For the execution of this activity, I made several forms and propose to the student to form words already known and new with them.

Figure 7 – Syllabic tokens

5.3 SET OF SYLLABIC STRIPS

This game was created with the objective of stimulating the process of word construction, in view of the difficulty that the student presented in writing, as previously mentioned. The student initially had to pair the syllables to recognize them and then form the words that were requested by me and those of his desire. In this game, the syllables are also fixed with velcro.

Figure 8 – Game of The Syllabic Strips

Source: author.

5.4 SYLLABIC FAMILY

Figure 9 – Syllabic Family

This material was made when the student already understood the syllabic formation process. We selected a consonant and placed it before the vowels (inside the booklet). The plug with the consonant was fixed by a velcro. Then we sang the song “Seu Serafim” [4] and the student said which syllables were formed.

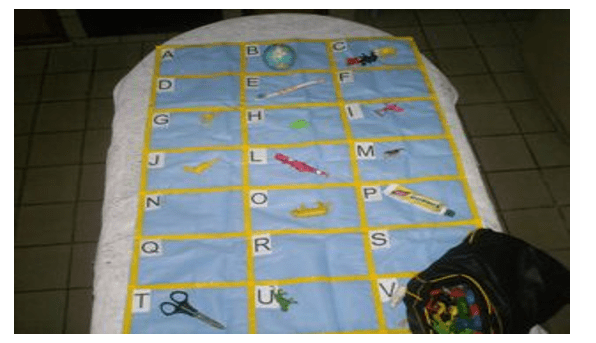

5.5 SET OF INITIALS OF WORDS

The game begins when we pass a bag full of objects. As the child picks up an object in the bag, she must place it on top of the letter that starts its name and then try to write the object name on a piece of paper. Material for making the game: TNT fabric, colored durex and varied objects that must be placed inside a bag to be removed by the child.

Figure 10 – Identifying the initial syllables of the words.

Another game that helped the student a lot at the beginning of the discovery of the words was the “window of words” (Fig.11). The game was made with EVA material and inside a strip, open only on the sides, the word was placed. When the student read the first syllable shown, he tried to guess the whole word. When I couldn’t, I had to read the following syllables and say what word was hidden. It was a way to stimulate and develop reading.

Figure 11 – Window of words

When I mentioned the importance of this game at the beginning of Frederico’s literacy process, it was because I used the names of the characters of the Turma do Cocoricó to form other words that the student could read in the window of the words. Example: MIMOSA and CACO – New word: MICO. This was one of the ways to arouse the student’s interest in reading other words. The red color was used to identify the syllables that gave rise to the new word (MICO), because, according to Troncoso and del Cerro (2004), it stimulates neurons in the brain and helps the child in their perception and visual memory.

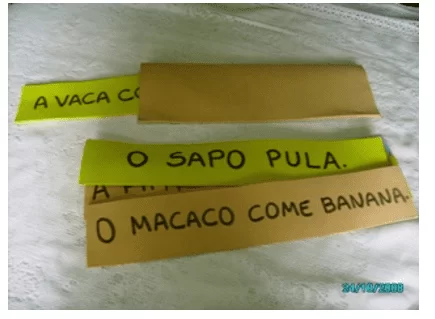

After the words came the sentences, which should be read as the strip began to come out of the “window”.

Figure 12 – Phrase window

These are just a few examples of games, games and activities that were developed to assist in understanding the student, developing their learning. Some games were held with me and Frederico only. But many others intentionally involved the whole class, with the aim of promoting socio-affective bonds between students, developing the relationship with their peers.

Thus, throughout the work, the student was able to perceive the process of constructing words, expanding his knowledge and developing reading and writing successfully.

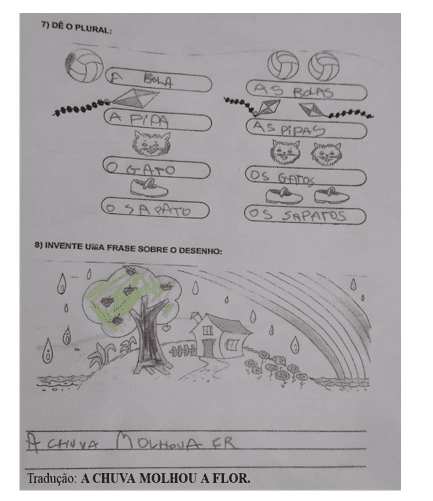

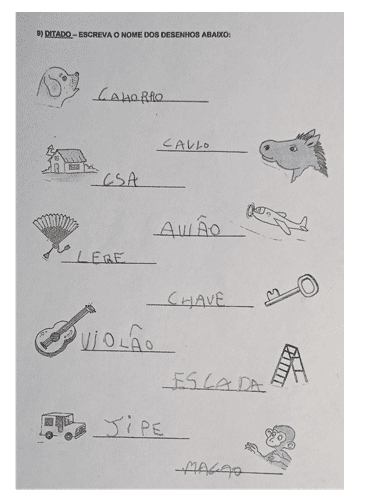

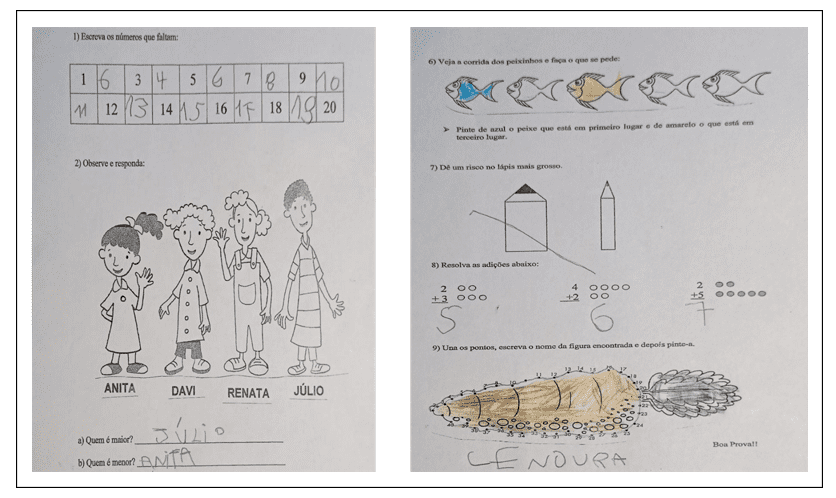

Below are some examples of activities that characterize the student’s initial performance and evolution throughout the process.

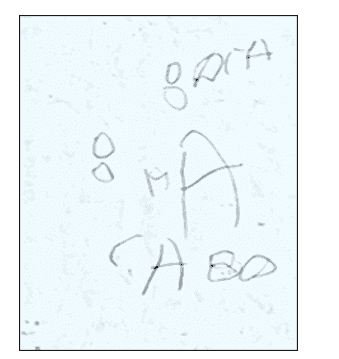

6. START OF THE PROCESS

Figure 13 – Copies of the Chalkboard of the Calendar of the Day Source: author. Figure 14 – Record made by the student of the Game Sylabic Manipulation – inversion of syllables: Mouth/Cable (Figure 6)

Source: author. Figure 14 – Record made by the student of the Game Sylabic Manipulation – inversion of syllables: Mouth/Cable (Figure 6)

Source: author.

6.1 EVOLUTION OF MOTRICITY AND KNOWLEDGE

Figure 15 – Developing writing.

Figure16 – Training the new vocabulary

Figure 17 -Training mathematical concepts

In view of the above, we can conclude that the action plan based on the Perceptual-discriminative Learning method presented positive results, arousing interest and motivating the student to learn, which allowed him to be literate and develop his competencies in other areas as well.

7. DISCUSSION

In this study, we present all the stages of the literacy process, the materials elaborated specifically for the peculiarities and interests of the student with DS, based on the method developed by Troncoso and Cerra (2004) that resulted, among other factors, in the acquisition of reading and writing. It was an individualized work, adapted to the student’s conditions and, initially, with the presentation of a vocabulary with words that the student understood and familiar to him.

In the pedagogical proposal to which the student was submitted, in addition to the acquisition of reading and writing, he can expand his interpersonal relationships, favoring self-esteem and socialization. Perhaps other students with DS do not reach the level of development in writing and reading like Frederico, but it is necessary to invest in the search for the best way to meet the unique needs of each student, with a teaching that has meaning for them.

The method proposed by Troncoso and del Cerro (2004) is not the only one capable of assisting in the literacy process of the person with DS, but it proved to be efficient and attractive to the student Frederico. For the authors, it “[…] proved to be effective, it is suitable for achieving a motivating learning, through which good results are achieved in terms of understanding, fluency and taste for reading.” (TRONCOSO; DEL CERRO, 2004, p. 55).

Many areas were developed in contact with Frederico, such as the cognitive area, which involves attention, memory and language; the affective-emotional area, involving interpersonal relationships, the rules of coexistence, socialization and activities of daily living and the area of motricity, with the development and improvement of fine, broad motor coordination, balance as well as self-perception. Consequently, all this contributed to the elevation of self-esteem, providing security and autonomy in relationships with everyone at school and outside it.

It was a work elaborated from stimuli, repetition of content, constant feedback, presentation of the material in small steps and respect for the student’s rhythm. Working with the name of the student’s beloved characters (significant to him) was the strategy used for the use of the method proposed by the authors.

Any interest shown by the student was used and channeled to teaching in order to involve him pleasurable in learning. Because, as Rubem Alves tells us “(…) I think we only learn those things that give us pleasure.” (ALVES, 1984 apud GADOTTI, 2002, p.259).

It is important that the teacher knows that the work must be performed and improved every day, through the experiences acquired in daily dealing with the limitations and potentialities of each student, specifically. Barriers can only be broken by building new forms of pedagogical doing, new ways of teaching and learning.

In this sense, it is clear that the work developed by the teacher with the student with SD needs to be differentiated and personalized. The activities must effectively start from real and concrete situations, so that there is no demotivation, so that the student does not lose interest in what is being developed.

It is important to note that even though people with DS have similarities in some characteristics does not mean that they all have the same picture, each of which is genetically unique. Therefore, they learn in different ways, being necessary the use of diversified activities that explore the areas where they are more easy to learn, with different learning strategies for each case.

8. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

In the inclusion process, the teacher is one of the main agents that will enable the participation and learning necessary for the development of the student with DS in the regular class. Therefore, it is necessary that the teacher be attentive to both the limitations and learning possibilities of his students, in order to intervene in order to facilitate the construction of knowledge, through strategies and curricular adaptations in the school daily life.

It is certain that the teacher throws on the student with cognitive disabilities a very great expectation in relation to their development and their learning, but it is necessary to understand that professional knowledge is built through time and perfected daily from experimentation, trial and errors, exchanges with peers and, mainly, interaction with their student. For this, the teacher needs to know his student, be attentive to his needs and elaborate work proposals that meet the specificities of all.

Adjusting teaching to individual learning characteristics of students is one of the biggest challenges of education even today and when it comes to students with SEN, the challenge becomes even greater, because we are accustomed to dealing with homogeneous knowledge.

It is hard work because it takes an attentive observation to know how and when to act, but immensely rewarding when the results begin to appear.

But despite all the obstacles, such as the lack of teacher training and physical and organizational structure in favor of the disabled, the work is being carried out and many teachers are developing effective actions in search of favoritism and growth, both social and cognitive, of students with DS.

We emphasize that this work was only possible because there were partnerships with the family/direction/supervision/teacher regent.

REFERENCES

ABBEDUTO, L.; WARREN, SF; CONNERS, FA Desenvolvimento da linguagem na síndrome de Down: do período pré-linguístico à aquisição da alfabetização. Ment. Retardar. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 2007, 13, 247–261

BRASIL. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Ações Programáticas Estratégicas. Diretrizes de atenção à pessoa com Síndrome de Down. ed., 1. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, 2013.

BUCKLEY, SJ; BIRD, G. Teaching children with Down syndrome to read. Down Syndr. Res. Prato. 1993, 1, 34–39.

CARRETTI, B.; LANFRANCHI, S. The effect of configuration on VSWM performance of Down syndrome individuals. J Intellect Disabil Res, v. 54, n. 12, p. 1058-66, 2010.

CHAPMAN, R.; HESKETH, L. Behavioral phenotype of individual with Down syndrome. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev., v. 6, n. 2, p. 84-95, 2000.

CORREIA, L. M. Educação Especial e Inclusão. Quem disser que uma sobrevive sem a outra não está no seu perfeito Juízo. 2.ªed. Porto Editora, 2003.

GADOTTI, M. História das Idéias Pedagógicas. São Paulo: Editora Ática, 2002

GASPARIN, J. L. Motivar para aprendizagem significativa. Jornal Mundo Jovem. Porto Alegre, n. 314, p. 8, mar. 2001.

KOLGECI, S.; KOLGECI, J.; AZEMI, M.; SHALA-BEQIRAJ, R.; GASHI, Z.; SOPJANI, M. Cytogenetic Study in Children with Down Syndrome Among Kosova Albanian Population Between 2000 and 2010. Mater Sociomed, v. 25, n. 2, p. 131-135, 2013.

LIMA FREIRE, R. C.; DUARTE, N. S.; HAZIN, I. Fenótipo neuropsicológico de crianças com síndrome de Down. Psicologia em Revista, v. 18, n. 3, p. 354-372, 2012.

PENNINGTON, B. F. et al. The neuropsychology of Down syndrome: evidence for hippocampal dysfunction. Child Dev, v. 74, n. 1, p. 75-93, 2003.

SCHWARTZMAN, J. S. Síndrome de Down. 2. ed. São Paulo: Editora Mackenzie, 2003.

TILSTONE, C.; FLORIAN, L; ROSE, R. Promover a Educação Inclusiva. Lisboa: Instituto Piaget, pp. 51-64, 2000.

TRONCOSO, M.V.; DEL CERRO, M. M. Síndrome de Down: leitura e escrita. Porto Editora – Portugal, 2004. ISBN: 972-0-34694-9.

APPENDICES – FOOTNOTES

2. Fictitious name to preserve the identity of the student.

3. Children’s series, produced and aired by TV Cultura, launched in 1996, which portrays the fun adventures and day-to-day life of a boy named Júlio and his friends. The cast is made up of puppets of people and animals. The show stopped being produced in late 2013, but continued to be reprised daily. Source: http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/fsp/1996/1/05/folhinha/6.html

4. Music Seu Serafim: Look there Your Serafim, this letter does so: B with A do BA, B with E do BE, B with I do BI, B with O do BO, B with U do BU.BA-BE-BI-BO-BU – BA-BE-BI-BO-BU (Unknown Author).

[1] PhD in Developmentodisorders (UPM); Specialization in Special Education (UNIRIO); Psychosocial Care in Childhood and Adolescence (UFRJ); Psychopedagogy (UPL).

Submitted: January, 2021.

Approved: March, 2021.