ORIGINAL ARTICLE

MARCHI, Cynthia Mariana Gonçalves Arroyo [1], NOZAKI, Maria Eduarda Pontes [2], MASSARI, Felipe Adolfo K. [3], HORTA, Maria Fernanda da [4], ABRAHÃO, Leonardo de Faria Bachelli [5], RANGEL, Lídia Magalhães [6], CASTRO, Valéria da Cruz Oliveira de [7]

MARCHI, Cynthia Mariana Gonçalves Arroyo. Et al. Need for training professionals in Special Education in a city in São Paulo. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 05, Ed. 11, Vol. 24, pp. 107-143. November 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/education/city-in-sao-paulo

SUMMARY

Special Education in all its areas has gained the spotlight in discussions and research throughout the country in order to understand, analyze or propose changes, aiming at continuing education in Special Education, promoting greater attention to the specific public. Thus, the students of the medical course perceived a need to evaluate the learning of teachers and trainees in working with children who have special educational needs in a school in the interior of São Paulo. It was, therefore, an exploratory and descriptive research that used qualitative and quantitative variables that allow mapping some results about this process of socialization and learning of special children. Indeed, the notorious implication is the recognition of the educational needs that teachers and trainees encounter in daily life with people with special needs. The results show that there is great didactic effort on their part to include students with disabilities and establish integrality from reality in the classroom to instruments of socialization and integral development of the person as a whole. However, the analyses point to the important concern of education professionals who demonstrate the acuity of greater training and recycling in the scope of Special Education, in fact, it is observed that there is a need to increase the qualification time of educators in view of the complexity that the task requires.

Keywords: special education, inclusive education, teacher training, trainees.

1. INTRODUCTION

According to the Brazilian Constitution (1988), in article 5, all are equal before the law, and this right is inviolable. In the same document, the subsequent article guarantees access to education as a social right. In this way, all citizens have ensured education equally. (BRASIL, 1988). The National Policy for Integral Attention to Child Health (PNAISC) reinforces in article 6 item VI the health care of children with disabilities or in specific situations and vulnerability with a focus on the inclusion of these children in thematic health care networks through the recognition of the specificities of this public for problem-solutive care. In suma, the excellence of PNAISC is based on the axes of the Unified Health System (SUS) that prioritize universality, integrality and equity. (BRASIL, 2015).

In 2015, Law No. 13,146, the Brazilian Law for the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities (Statute of Persons with Disabilities), was promulgated, aimed at ensuring and promoting, on an equal basis and without discrimination, the exercise of the fundamental rights and freedoms of persons with disabilities, aiming at their social inclusion and citizenship. (BRASIL, 2015). It is noteworthy that the school inclusion of students with special needs is provided for by Decree 7,611 of 2011. According to Art. 1, § 1, specialized educational care is considered the set of activities, accessibility resources and pedagogical organized institutionally, provided in a complementary or supplementary way to the training of students in regular education. (BRASIL, 2011).

When analyzing the current context of Brazilian schools, it is noted that this prerogative is not valid, especially when focusing on the educational situation of individuals with disabilities, whether they are of any nature.

The inesage with inclusive education, according to Marcus Mazzotta (1982), is based on the historical stereotype that places the disabled in the immutable condition of “invalid”, leading to the marginalization of these and, consequently, the omission of specific services to meet the needs of this population portion. (MAZZOTTA, 1982).

The contempt for didactic coverage is proven in Brazilian schools that, for the most part, do not have the necessary contribution to receive students with disabilities, since their infrastructure is inadequate, their teachers are unprepared and teaching materials are not adapted according to individual needs. Thus, students who are enrolled in regular education and require special care, mostly, are without receiving it, causing the so-called “inclusion-excluding” to refer to the perverse logic masked in the policies of generalization of Basic Education. (FREITAS, 2002).

In order to resay educational indifference, decree no. 3 was promulgated in 1999. 298, which provides for the National Policy for the Integration of Persons with Disabilities, establishing the compulsory enrollment of Persons with Disabilities, as well as considered, in Art. 24, Special Education an educational modality. (BRASIL, 1999). In addition, the School Health Program (PSE) was established in 2007, which allows the interaction of health services with educational services, aiming at, executing and monitoring actions to prevent, promote and evaluate the health conditions of students, as well as the training of education professionals. (BRASIL, 2007).

Unrestricted education aspires to equal opportunities without discrimination. (BRASIL, 2011). This guarantee of an inclusive educational system occurs from the variety of educational services and the consideration of the diversities and personalities of each subject, aiming to meet the individual differences of the students for a qualitative and meaningful learning, providing personal and social appreciation. (MAZZOTTA, 1982; FERREIRA, 2005). Therefore, the presence of special educational needs, not just the presence of a disability, determines whether a student should receive a special education. (MAZZOTTA, 1982).

2. GOALS

To analyze the learning needs of teachers and trainees at work with children who have special educational needs in a school in the interior of São Paulo.

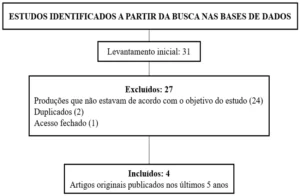

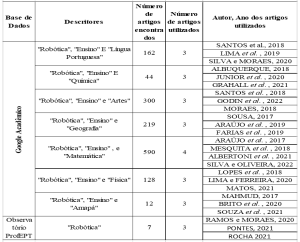

3. METHODOLOGY

The research included 17 professors from the teacher Maria Martins and Lourenço School and 45 trainees from the Pedagogy course of the University Center of Votuporanga were also invited. The research was carried out at the teacher Maria Martins e Lourenço School, which is located in the Pozzobon district and the University Center of Votuporanga, both located in the same municipality.

At first, a literature review was performed and then the students of the medical course applied a questionnaire, thus being an exploratory and descriptive research, using qualitative and quantitative variables.

On the first day, the objective was to collect statistical data of students of the 2nd and 8th period of the Pedagogy course of the University Center of Votuporanga – UNIFEV – to analyze the experience of these and difficulties encountered in special education. Therefore, initially, the motive and objective of the present study were justified, in addition to encouraging the participation of pedagogy students.

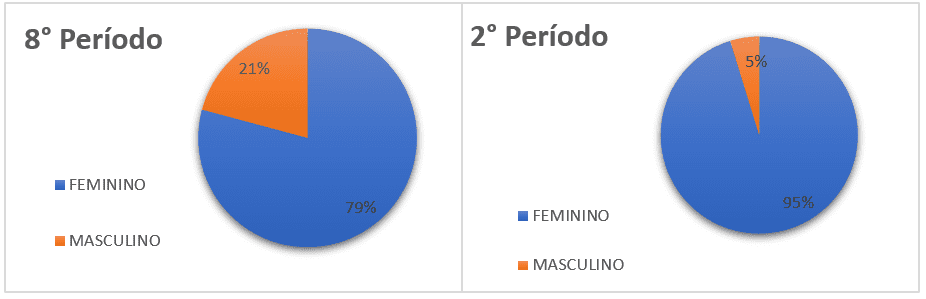

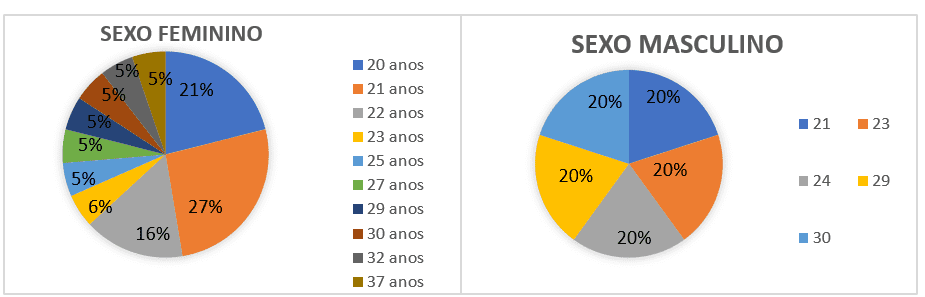

A questionnaire was then applied to 100% of the students present in the 2nd and 8th period of the Pedagogy course of the University Center of Votuporanga – UNIFEV. During the survey, 21 students from the 2nd period were present, including 20 females and 1 male. Likewise, there were 24 students from the 8th period, 19 females and 5 males.

The second day was to identify the needs and lack of resources of teachers and evaluate their level of knowledge in relation to the promotion of adequate special education, according to the particularities of each student with disabilities. Thus, at first, the reasons, objectives and relevance of this research were explained, and then applied a questionnaire, individually and confidentially, with 11 questions based on the reality of resources, activities, preparation, difficulties and among other topics focused on special education. During the application of the questions, 17 teachers were present, 2 men and 15 women. It was, therefore, an exploratory, descriptive research with qualitative and quantitative variables. After that, the responses were analyzed by the Unifev students in order to detect the difficulties presented at school.

The third meeting aimed to clarify the doubts of teachers regarding the difficulties encountered by them in the day-to-day with regard to students with disabilities and their particularities. The conversation wheel was held at the Unifev educational institution, which is located in the downtown neighborhood in Votuporanga- SP. At first, the president of the APAE – Association of Parents and Friends of Disabled People Votuporanga was presented to the teachers and then explained the reasons, objectives and relevance of this research. Subsequently, the discussion was initiated, which addressed issues such as social inclusion, the importance of APAE, prejudice against disabled people, and tips for teachers to optimize the learning of special students in classrooms. During the discussion, 16 teachers were present, 1 man and 15 women.

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

First day:

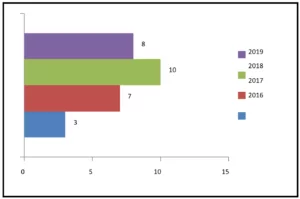

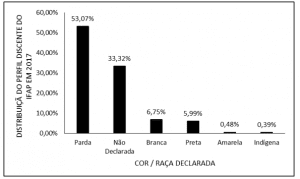

Graph 1 – Distribution of Pedagogy Students according to gender and period

During the application of the questionnaire and from the analysis of Graph 1, the prevalence of female students in both periods surveyed was visible. This is in line with what Vianna proposes (2002), in which the feminization of education occurs both at the professional and academic level and transcends the issue of numerical composition, and female meanings can be identified in teaching activities regardless of who performs them. That is, historically the pedagogy course was constructed from practices considered feminine, since the profession involves the education of children, good relations with family members, friendly communication, patience, kindness, understanding, socially ethical conducts, among other characteristics, which are attributed to the female sex.

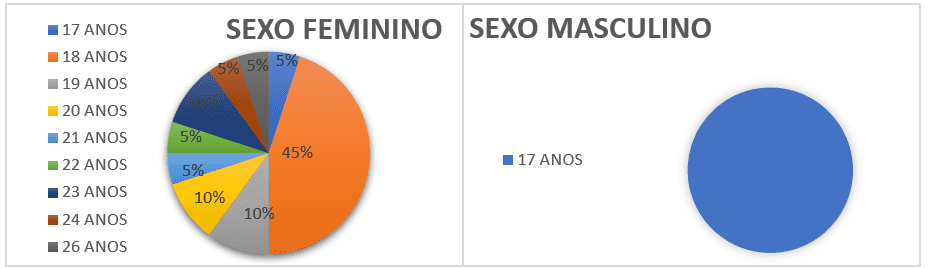

Graph 2 – Distribution of Students of the 2nd Pedagogy Period according to gender and age

Graph 3 – Distribution of students of the 8th Pedagogy Period according to gender and age

Analyzing the age parameters found in the rooms (graphs 2 and 3), it was possible to observe the predominance of young academics. In the 2nd period, the students are mostly between 17 and 18 years old, while in the 8th period the majority is between 20 and 23 years. This precocity or longing for admission to higher education agrees with that proposed by Bloss (1998), which considers professionalization as a fundamental part for consolidating the interests of the ego in the final phase of adolescence. Thus, most young people seek to enter as soon as possible in view of the longing for a promising future through higher education. (BLOSS, 1998).

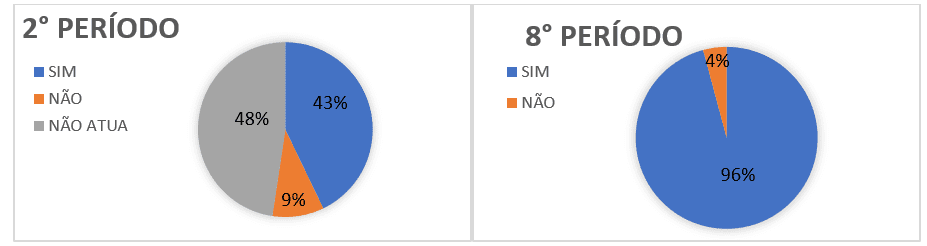

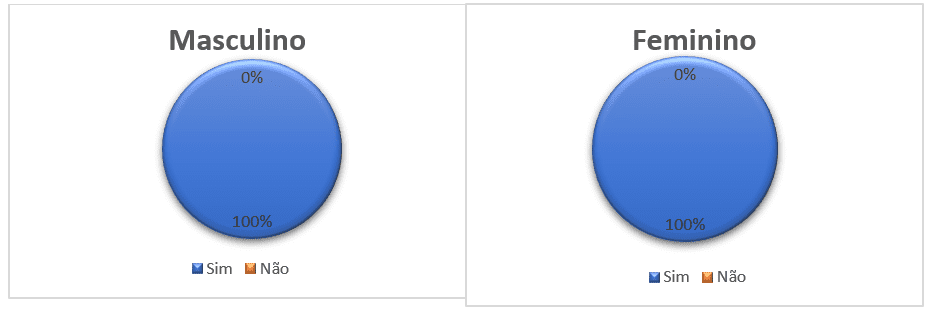

Graph 4 – Distribution of Pedagogy Students of the 2nd and 8th Period according to the Presence of Special Students in Teachers’ Schools

The presence of students with special needs in the trainees’ schools (Graph 4) is high, being practically negligible the number of schools that do not have special students when compared to the number of trainees working. This panorama complies with the proposed Law of Guidelines and Bases of National Education, Law No. 9,394/96, as well as is ensured by the Constitution of the Federative Republic of Brazil (1988), which advocate the adequacy of education systems to meet the specificities of students and universal education. (BRASIL, 1996, 1988).

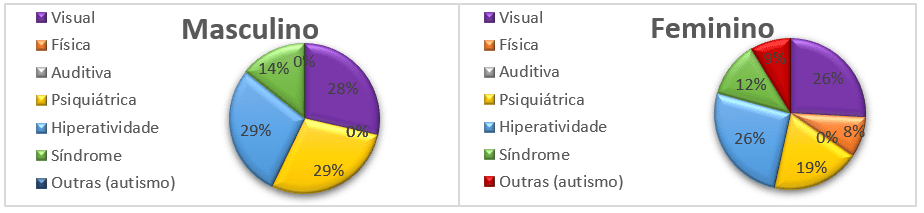

Graph 5 – Distribution of Pedagogy Students of the 2nd and 8th Period according to the special needs found in internship schools

The graph above allows us to conclude that the special need for higher incidence reported by the research participants is hyperactivity, usually associated with attention deficit disorder (ADHD), which is considered common at school age and obtains a prevalence of 3 to 5% of children at this stage. (PASTURA et al., 2007). In addition, it is worth mentioning that there is a high incidence of seeking care already with an uncorrect diagnosis of ADHD, evidencing that many children are not, in fact, carriers of hyperactivity and that the prevalence rate is subject to variation. (GRAEFF et al., 2008).

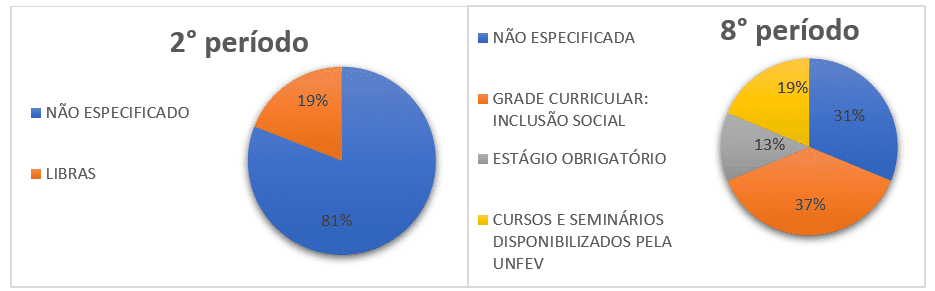

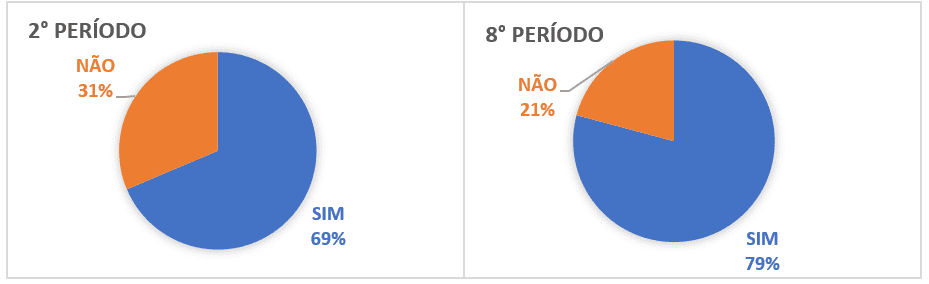

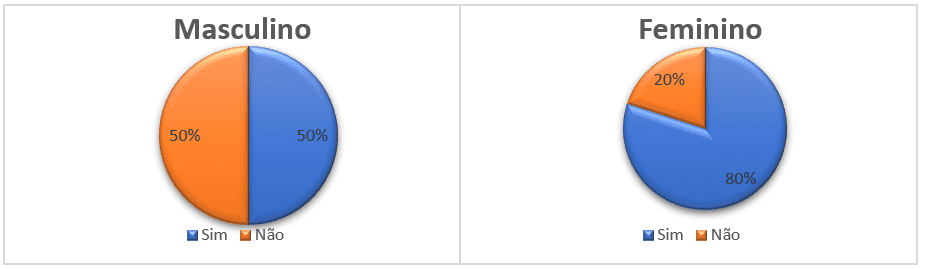

Graph 6 – Distribution of Pedagogy Students of the 2nd and 8th Period according to the opportunities of preparation in Special Education

From the results presented by graphs 6, one can observe a discrepancy of responses between the 2nd and 8th period, which can be justified by the fact that the students of the first year of the pedagogy course will contact the curriculum corresponding to special education in the next periods. Therefore, it is worth noting that teaching to the special child incorporates social inclusion, that is, it is a portion of the acceptance by teachers that this teaching is their responsibility and therefore should be prepared for such work. (MITTLER, 2003).

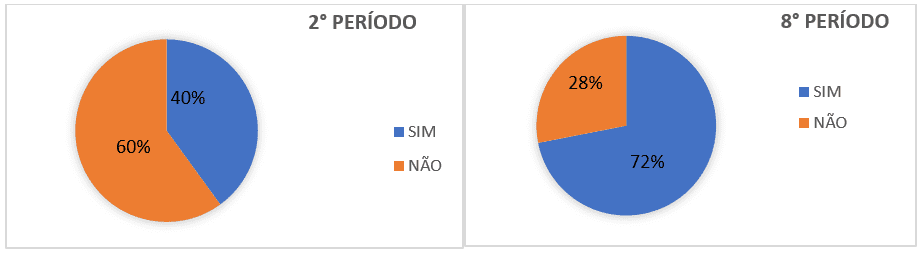

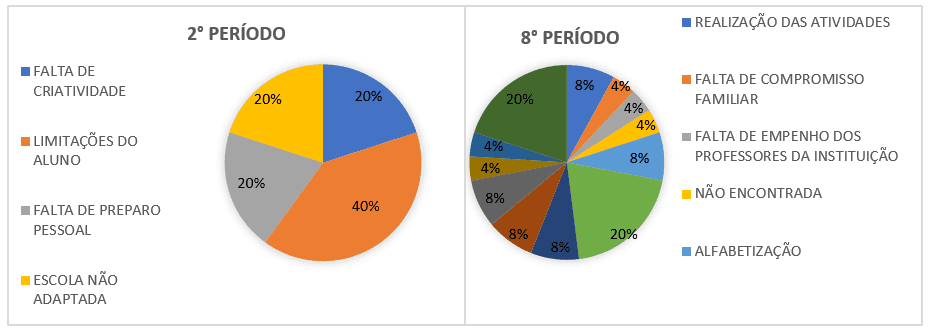

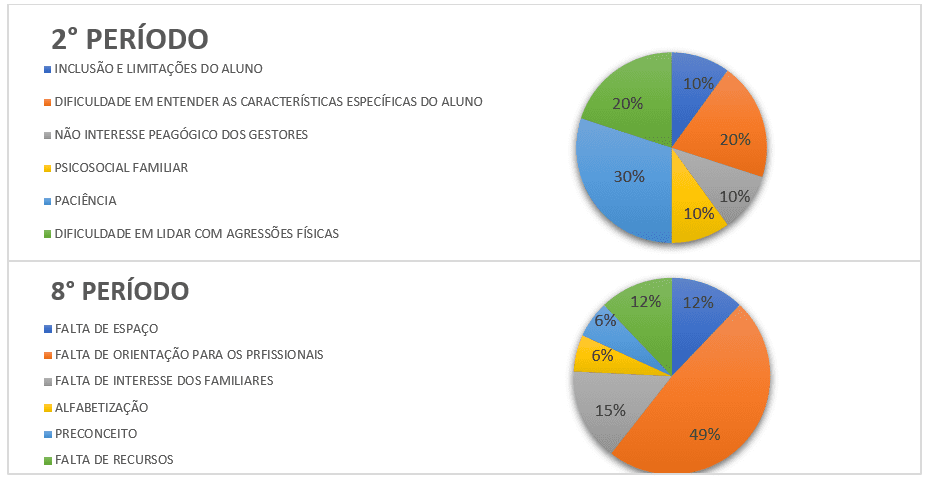

Graph 7 – Distribution of Pedagogy Students of the 2nd and 8th Period according to the difficulties encountered in performing educational activities with special students

Graph 8 – Distribution of Pedagogy Students of the 2nd and 8th Period according to the access of preparation for special education

Graphs 7 and 8 indicated that the lack of preparation of teachers regarding special education is the main difficulty in working with special students, which directly reflects on the limitations of the student (the main cause pointed out by the students of the 2nd period), that is, the absence of preparation makes the difficulties of the special student become a hindrance to the learning of the same. Therefore, it is necessary that both the students of the pedagogy course and the professionals already active are trained for special education, based on the fact that the presence of the teacher is of paramount importance for the teaching of any and every human being, since it is he who is in direct contact with the student. (SKINNER, 1972). In addition, it is possible to affirm that a part of the students of the first year already seek some form of preparation to deal with special students before contacting the curriculum corresponding to this subject, while most students in the last year of the course entrust their basis for special education only to the curriculum of the course.

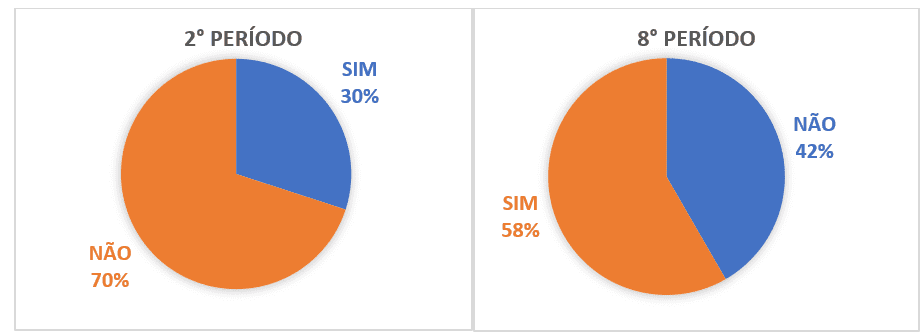

Graph 9 – Distribution of Pedagogy Students of the 2nd and 8th Period according to the adaptation of the schools of activity to the special needs

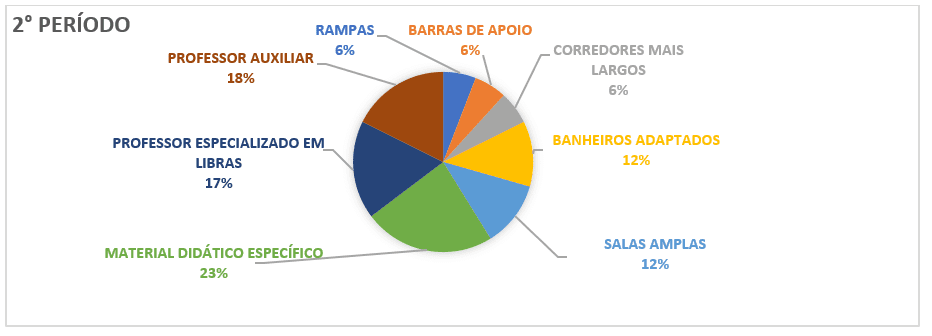

Graph 10 – Distribution of Pedagogy Students of the 2nd and 8th Period according to the needs of infrastructure incrementation in the schools of activity

Leveling the rates of adaptation of the schools in which the trainees work, it is evident that the vast majority of schools free of adequate physical and psychological structure to receive special students, being 70% of the schools of the trainees of the 2nd period and 58% of the schools of the trainees of the 8th period. In short, to characterize this lack, the trainees cited the lack of specific teaching material, the absence of a teacher specialized in pounds and the absence of an auxiliary teacher, as the main reasons for insufficiency for a relevant scope of special education in schools. In addition, they have as adversities encountered as well, absence of ramps and support bars, corridors and narrow rooms and bathrooms without adaptation. Thus, it is notorious a great incongruity in the reality experienced by the trainees and the Brazilian laws that govern special education, especially due to the existence of the National Policy of Special Education that in the Perspective of Inclusive Education aims at the access, participation and learning of students with special educational needs, ensuring urban, architectural accessibility, in furniture and equipment , in the transport, communication and information offered to such students. (BRASIL, 2008)

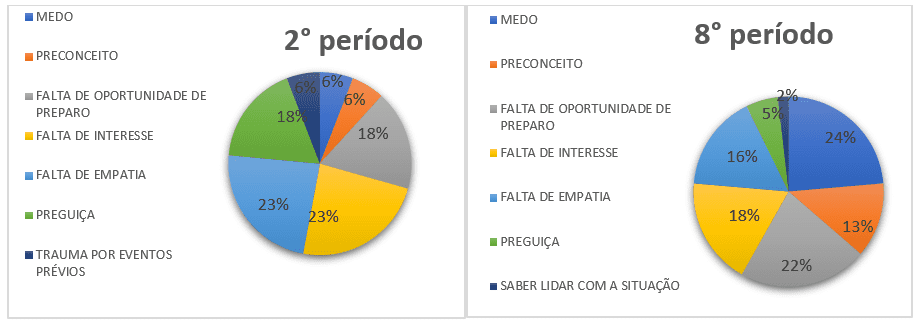

Graph 11 – Distribution of Pedagogy Students of the 2nd and 8th Period according to the perception of Resistance found by education professionals in working with students with special needs

Graph 12 – Distribution of Pedagogy Students of the 2nd and 8th Period according to the types of resistances found

Graph 12 shows an equivalent perception among students in the 2nd and 8th periods regarding the resistance of education professionals to deal with special education. Unfortunately, it is believed that this reaction is based on factors that relate to historical concepts related to people with disabilities, the student of special education and also to the students of the last periods of pedagogy, who believe that they will not come across such students. (HONNEF, 2011).

Detailing the reasons for this resistance, the students of pedagogy place as lack of preparation, interest and empathy the main causes for the reluctance of educators to special education. In addition to these pretexts, fear, laziness and prejudice were also mentioned, which makes clear the urgent need to deconstruct mentalities, postures and behaviors, in addition to demonstrating that universalist policies have not been able to achieve what they promise: to treat everyone equally. (CURY, 2005).

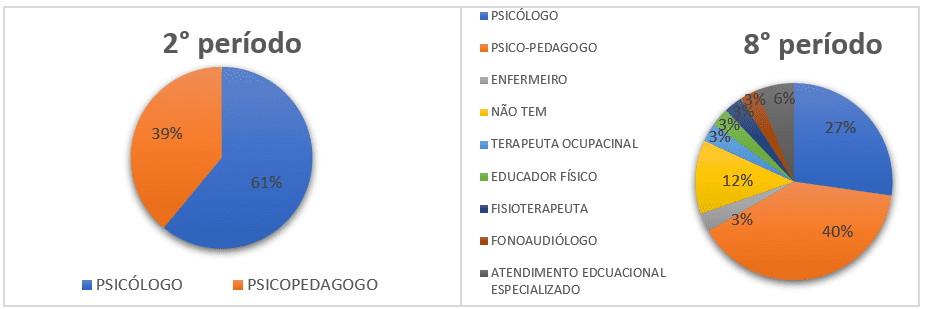

Graph 13 – Distribution of Pedagogy Students of the 2nd and 8th Period according to the presence of specific professionals to work with special students in internship schools

Teacher education is also among the most emerging demands for the effectiveness of the inclusion process, because, currently, it is a consensus that the qualification of educators influences the advancement of educational reform. Thus, the lack of preparation of teachers is one of the most cited obstacles to inclusive education, which has as its effect the strangeness of the educator with that subject who does not conform to “the standards of teaching and learning”. (BRASIL, 2005). This picture is in line with Graphs 25 and 26, because there is a low performance of teachers who have been educated in special education (6%) or in courses focused on the well-being of students with functional dysfunction (speech therapist – 3%; physiotherapist – 3%; occupational therapist 3%). At the same time, schools with no professionals are noted (12%). However, there is a concern about the mental health of students, which can interfere in the learning process.

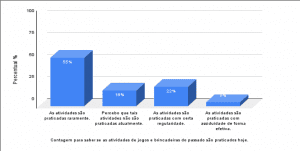

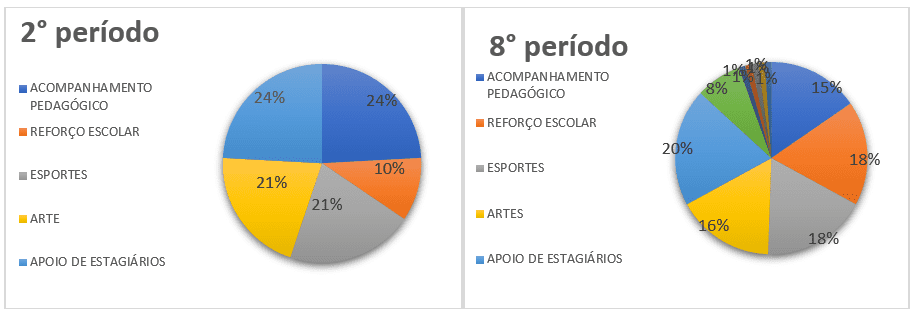

Graph 14 – Distribution of Pedagogy Students of the 2nd and 8th Period according to the activities performed specific to special students

Regarding the activities performed in the schools in which the trainees work (Graph 14), it is observed that the 2nd period, because it has less experience in the area of activity, has a smaller range of activities than those in the 8th period and that this year has a limitation of complementary resources offered by educational institutions. This scenario is susceptible to concern, because the educator’s performance must go beyond the transmission of curriculum content, prioritizing assimilation by the student, since without it there will be no learning, memorization and practical application of knowledge. Thus, it is necessary to have a school environment that allows accessibility to the physical and instrumental environment (materials and resources that minimize sensory and motor difficulties); have motivating, joyful and affirmative practices; there are strategies rich in stimulation and diversified when necessary (e.g. audiovisual resources, objects of different materials, colors and textures); quieter activities are carried out and associative memory is worked on; that there is use of assistive technologies (ATs) and information technologies (ITs) to integrate strategies for stimulating cognitive processes; among many other resources that can provide a real training of the special student not only academically, but also focused on social interaction. (SANTOS, 2012).

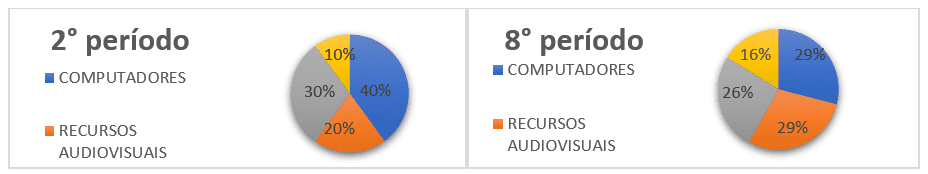

Graph 15 – Distribution of Pedagogy Students of the 2nd and 8th Period according to the resources used for inclusion in internship schools

From the analysis of graphs 29 and 30, it is evident that the use of computers prevails as a way to promote inclusion in the school, with 40% of the schools of the trainees of the 2nd period and 29% of the schools of the trainees of the 8th period. This fact has relevance within the context of special educational training, since the technologies assisted organize and strengthen language, allowing effective communication and the acquisition of school and social skills, vital to ensure its full development and autonomy, to perform activities both at school and outside it. (HEIDRICH, 2003).

Graph 16 – Distribution of Pedagogy Students of the 2nd and 8th Period according to greater difficulties encountered to work with special students

Analyzing graph 16, it is possible to perceive the visible presence of concern about the absence of the family’s interest in getting involved with the education found by the 2nd and 8th period of Pedagogy. The participation of the family corresponds to the pedagogical ideals of participatory democratic management and in the understanding that, joint work, can bring many benefits to the school and students, ensuring the increase of conditions for a better learning and development of the child. (BRASIL, 1996). However, even though the interaction between family and school is extremely important, it is perceived that the participation of parents in school is still relatively low.

Taking into account the inexperience of the 2nd period in the practical area, due to its recent entry into the pedagogical field, it is noticeable the fear about patience when dealing with special students. This fear demonstrates empathy and is of paramount importance because special education teachers stress that there must be a genuine motivation, dialogue, patience, commitment and responsibility of the teacher in planning thinking of the student for inclusion to happen. (THESING et al., 2018).

On the other hand, the greatest anxiety of the interns of the 8th period, because they are close to the graduate, is the lack of guidance for the professionals. According to Bueno (1999), given the current conditions of education in Brazil, it is not possible to include children with special educational needs in a regular education without the support of a specialized professional with some guidance and assistance. Thus, an inclusive education is one composed of a teaching adapted according to the differences and needs of each student, in an integrated way to the regular system. Thus, the essential itis for this concept to be effective is the adequate and continuous training of the teacher. (SANT’ANA, 2005).

Second Day:

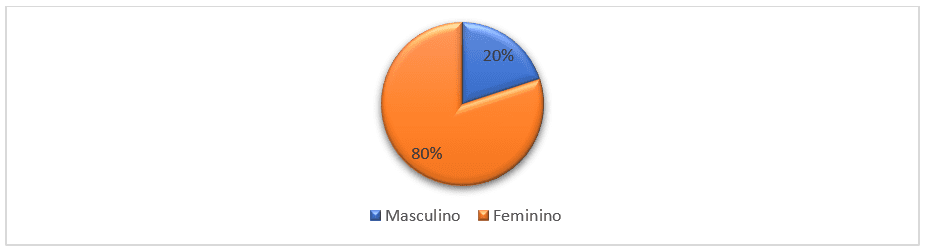

Figure 17 – Distribution of Teachers according to gender.

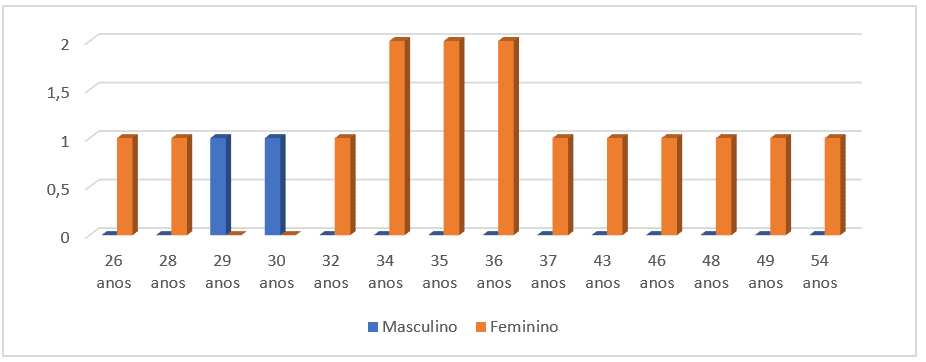

Graph 18 – Age according to gender.

According to graphs 17 and 18, most education professionals are female (80%) aged 36 years, while only 20% are men, these being between 29 and 30 years. This panorama is in accordance with the 2010 Brazilian census, in which more than half of the Brazilian population was composed of women (51.03%), and the age group of 35 – 39 years represented 3.7% of this total. (IBGE, 2010).

In addition, it is noted that among pedagogy professionals there is a female predominance, because this professional activity is marked by care, love, patience, dedication, vigilance and zeal, historically feminine characteristics. (LOURO, 1997). Thus, the profession of educator is considered an extension of the home, which, in many times, creates stereotypes and prejudices about its undergraduates and professionals, evidencing a machismo still rooted in Brazilian society.

Graph 19 – Presence of Special Students in Teachers’ Schools.

Graph 19 indicates that all teachers of both sexes have students with special needs in their classrooms. This situation is in line with the Brazilian Constitution of 1988, which establishes education as an inviolable right and for all. (BRASIL, 1988). This fact is reaffirmed through Law No. 13,146 of 2015, in which education is considered a right of children with singular needs, in addition to determining that learning be offered with school support, inclusive pedagogical practices, teacher training in special education, among others. (BRASIL, 2015).

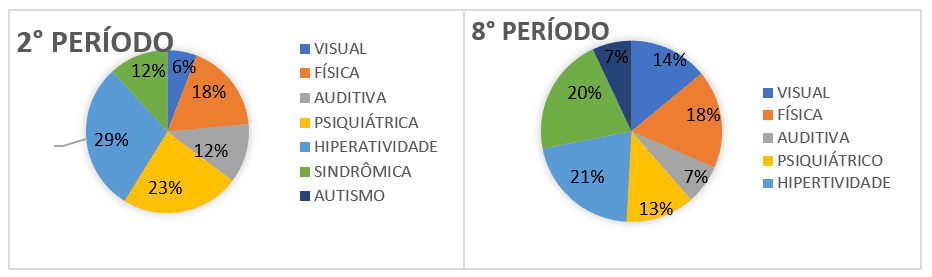

Graph 20 – Distribution of the prevalence of types of disabilities in teachers’ schools.

Graph 20 shows a prevalence of psychiatric, visual, hyperactivity (ADHD) and autism needs, followed by syndromes and physical disability.

Considering psychic needs, mental and behavioral disorders have a strong impact on individuals, families and communities. Individuals suffer not only because of their pathology, but also because they are excluded from social activity (e.g., work and leisure) due to discrimination. (SANCHES et al., 2011). In this sense, it should be considered that the social reintegration of the individual with mental disorder implies involvement in the school environment, since this constitutes the main place of social and affective bonds during childhood.

With reference to students with visual needs, education professionals need to have knowledge about the limitations of these individuals, as well as about the education and rehabilitation system for them. The school and rehabilitation must act together, aiming to meet the real difficulties of the child’s visual impairment. (MONTILHA, 20019). In view of this, schools should offer expanded or Braille materials, Braille class, sensory activities, among other ways to include the student in the school and social environment.

In relation to ADHD, the main clinical manifestations of the disease are perceived in the classrooms through dispersive behaviors, excessive agitation, poor performance, among others. Thus, it is necessary to train education professionals in order to sharpen their perceptions about behavioral changes of their students, aiming at possible referrals and early diagnoses. In addition, the teacher’s best qualification makes it possible to optimize the learning of children with ADHD through more playful activities and more participative methodologies. In this sense, such positive actions, practiced by the teacher, can generate significant changes in the student’s learning process, consolidating it. (DE LIMA, 2014).

Regarding students with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), these are characterized by compromising or accentuating intellectual development, restrictions on social interaction, communication and interest activities, and these clinical manifestations are extremely specific of each individual. (CABRAL et al., 2017). Thus, it is necessary that the teacher has knowledge about the individualities and specificities of each student with ASD for the preparation of classes, as well as inclusion of the child in the class. (FERRAIOLO et al., 2011).

With regard to students with Syndromes, for a long time it was believed that these people were unable to learn and, therefore, were excluded from schools. Currently, even with so much information about the various syndromes, prejudice persists, being considered the greatest barrier to the inclusion of these students. (SOUSA et al., 2017).

From the perspective of students with physical disabilities, these have their schooling impaired even in common situations in teaching due to the limitations of locomotion, posture, use of hands, vigor, vitality and agility. (MAZZOTTA, 1993). Therefore, they need to be attended as a whole by qualified professionals aware of the educational needs they may require in the context of the regular school. (MELLO et al., 2013).

Finally, with regard to hearing loss, it is undeniable that most deaf students have suffered school exclusion throughout history due to the difficulties arising from language. Therefore, deaf children, mostly, are lain behind in schooling, without adequate development and with a knowledge below expectations for their age. Thus, there is an urgent need to develop educational proposals that meet the needs of deaf subjects, favoring intellectual, motor, psychological and social development. (LACERDA, 2006).

Graph 21 – Preparation of teachers in Special Education.

From graph 21, it is noted that most professionals had opportunities to prepare for work with children with special needs (50% of men and 80% of women), either by lectures or courses. Thus, professional training is within the recommendations of Law No. 12,796, of April 4, 2013, which in its Art. 4th, item III, establishes that students with disabilities, global development disorders and high skills or gifted, should receive specialized and free educational care in the regular school system. (BRASIL, 2013).

However, it is notepoint that there are still teachers without qualification, and this is directly related to lack of knowledge and unpreparedness, which can impair the learning of the special child. Therefore, the current and great challenge for teacher training courses is to produce knowledge so that they can responsibly and effectively play their role of teaching and learning for and about diversity. (PLETSCH, 2009).

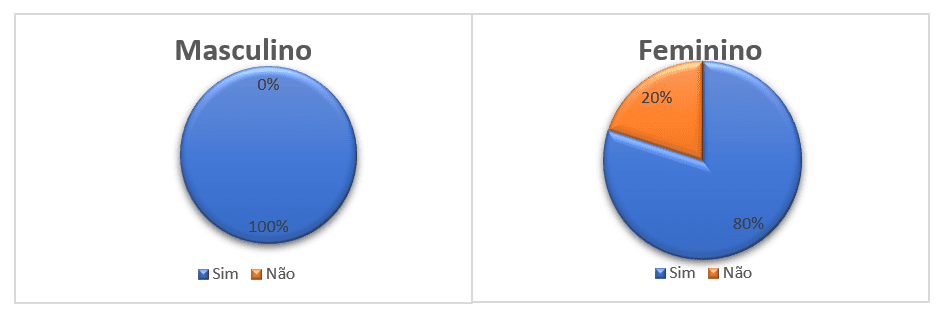

Graph 22 – Distribution of the opportunity in working with special children.

Teachers’ opportunity to teach children with special needs also gains prominence among the most emerging demands for deepening the inclusion process. According to the Salamanca Declaration, all individuals with special educational needs should have access to the regular school and that it is able to support them within a child-centered Pedagogy, satisfying their needs. (SALAMANCA, 1994). In addition, the same document states that by the principle of inclusive education, in law or policy form, all children have to be enrolled in regular schools. (SALAMANCA, 1994). Having said that, it is noted that the data obtained during the research are in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration and brazilian inclusive policies, since 100% of teachers and 80% of teachers work in the classroom with special children, which indicates a school inclusion of people with disabilities.

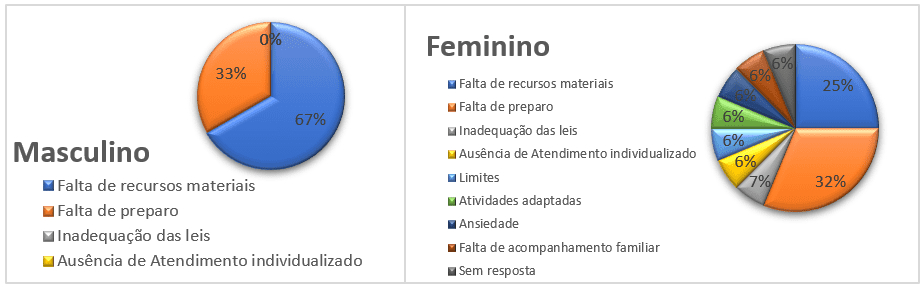

Graph 23 – Distribution of teachers according to the difficulties encountered in working with special children.

From the analysis of graph 23, it is evidenced the lack of material resources and preparation of teachers to develop activities with students with special needs. These may present significant changes in the process of development, learning and social adaptation, and each student presents unusual interests, different levels of motivation, unusual ways of acting, communicating and expressing their needs, desires and feelings. (BRASIL, 2006). In a moment, teachers have difficulties in how to deal with the particularities of each student, because the activities developed will need to be reformulated and adapted to achieve greater success, taking into account the expectations of appropriate attitudes.

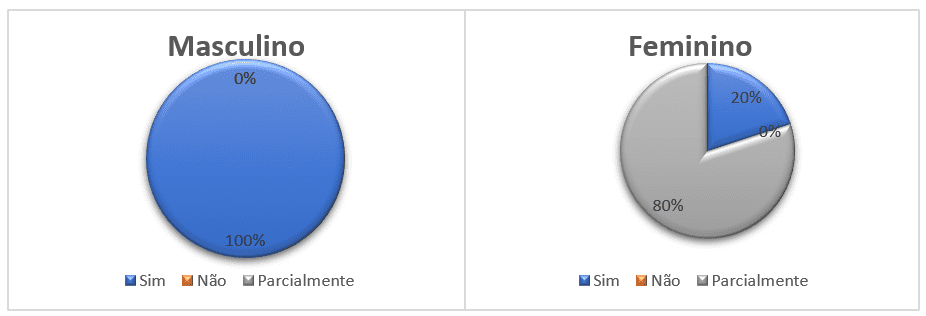

Graph 24 – Distribution of teachers according to the adaptation of the school.

Regarding the adaptation of the school to receive special students (graph 24), it was observed that teachers reported the presence of 100% adaptation in the schools in which they work, while 80% of the teachers reported partial presence of adaptation. In this context, it is worth remembering that according to the Salamanca Declaration, education systems should adapt to the needs of children and not the other way around, respecting the pace and nature of the learning process, assuming that “human differences are normal”. (SALAMANCA, 1994). It is worth noting that disability is a different characteristic present in this diversity that cannot be denied, because it interferes in the way people are, act and feel. (BRASIL,1994). Thus, Inclusive Education challenges the homogenization of students, according to criteria that disrespect human diversity.

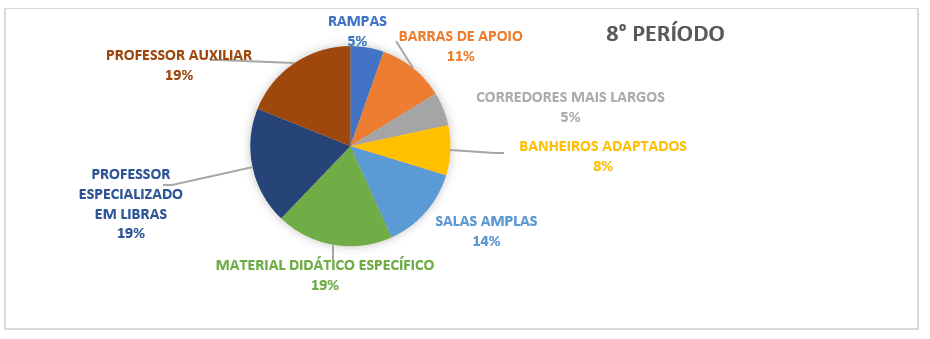

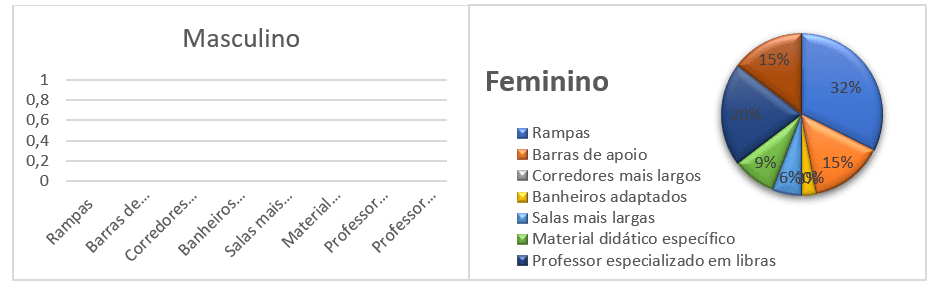

Graph 25 – Distribution according to the increase in school infrastructure.

Analyzing the distribution according to the increase in school infrastructure (graph 25), it was found that the teachers evaluated believe there is a lack of accessibility due to the lack of ramp incrementation (32%), a teacher specialized in pounds (20%), support bars (15%) and assistant teacher (15%). Therefore, the school should be trained to welcome students with special educational needs who have some physical, intellectual, visual, etc. disability. For this, it is necessary, through a joint action, to promote accessibility through the removal of architectural barriers, the adaptation of furniture and the production of didactic-pedagogical materials adapted for these students, according to their educational needs. (EDIER, 2000).

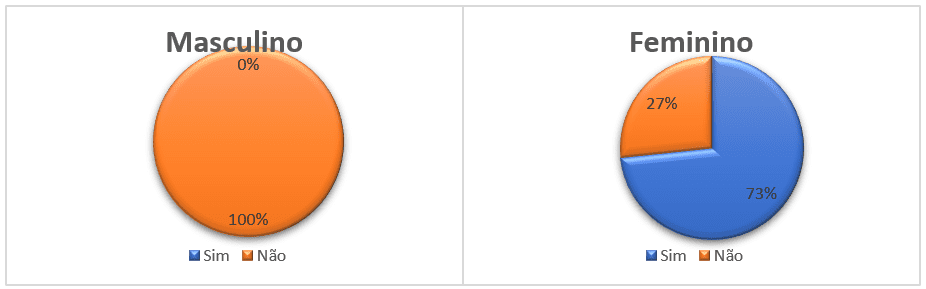

Graph 26 – Distribution of the Perception of Resistance of professionals in Working with Special Children.

When analyzing graph 26, it is noticed that none of the male interviewees believes there is resistance in the profession when teaching special students. In relation to the interviewees, these proved to be more critical, since about 3/4 of them claim to encounter objections. On living with people with disabilities, the emphasis given to this condition is emphasized, overshadowing other characteristics, which disconsiders the subject in its singularity. (NUNES et al., 2015). Consequently, it is noted that the prejudice that the disabled is their disability and lives according to it still persists, eliminating the subject to overcome the disability. (AMARAL, 2004).

In education, the focus on disability is also present, which calls into question inclusive education, because the belief that disability is the axis that defines and dominates the whole personal and social life of subjects ends up building a vulgar clinical process. (SKLIAR, 1997).

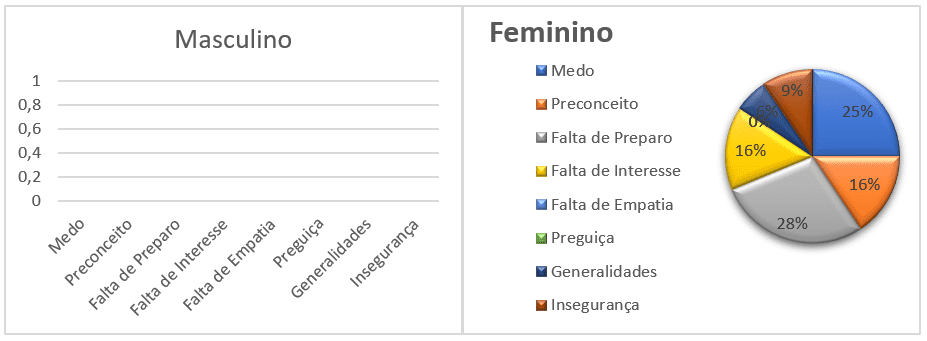

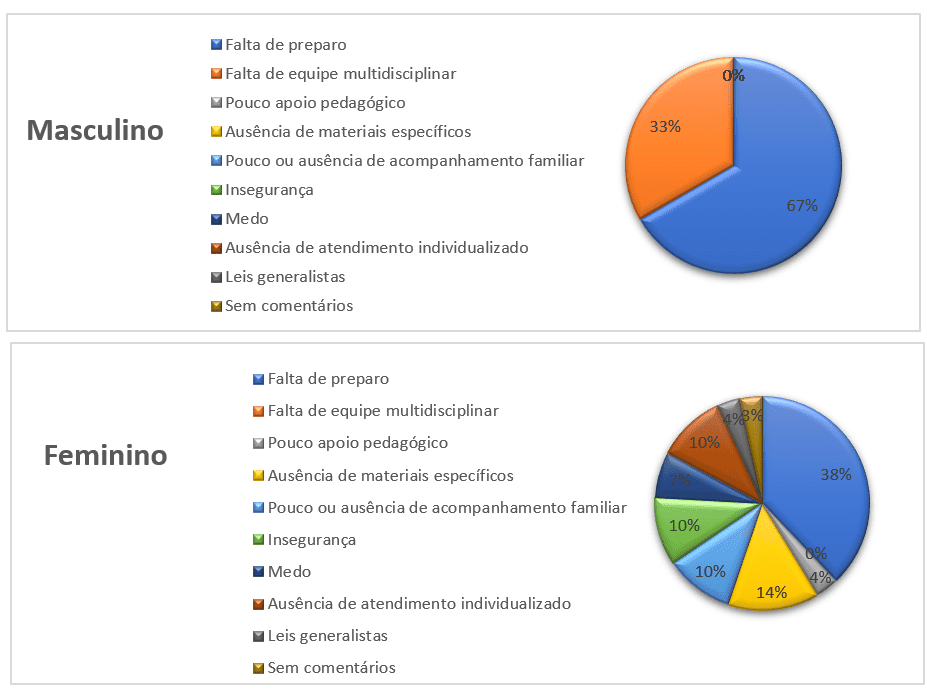

Graph 27 – Distribution according to the type of resistance found

Regarding the data covered in graph 27, it is noted that none of the male interviewees believe there is resistance on the part of their colleagues in the profession to work with special children. In females, most women (73%) they say they perceive aversions in the exercise of the profession when it is related to the most difficult learning process, and there is a higher incidence in the lack of preparation during training of the professional pedagogue (28%), followed by fear of acting (25%) due to physical aggression and responsibilities in the process of intellectual growth and development, for example, and lack of interest of the professional in acquiring knowledge, in addition to the presence of prejudice (16%). In view of this, although school inclusion is guaranteed through item III of Art. 208 of the Brazilian Constitution that refers to specialized educational care in the regular school system; be reiterated by the National Policy of Special Education that aims to support the regular education system for the insertion of people with disabilities, among many other government policies, the insertion of special students still bumps into the personal consideration of the teacher, their experiences, their beliefs, their opinions, their dispositions and psychological resources to perform such work. (FARIA et al., 2018). Thus, it is observed that the emotional and psychological preparation of professionals for the new work that is required of them is also relegated.

Thus, inclusive education can be considered full only for a reality of laws, since there remain various resistances to its implementation in institutional practices and projects. Thus, “equality” of pedagogical practice serves as a mask and justification for indifference with regard to real inequalities in the face of teaching and the culture transmitted. (BOURDIEU, 1998).

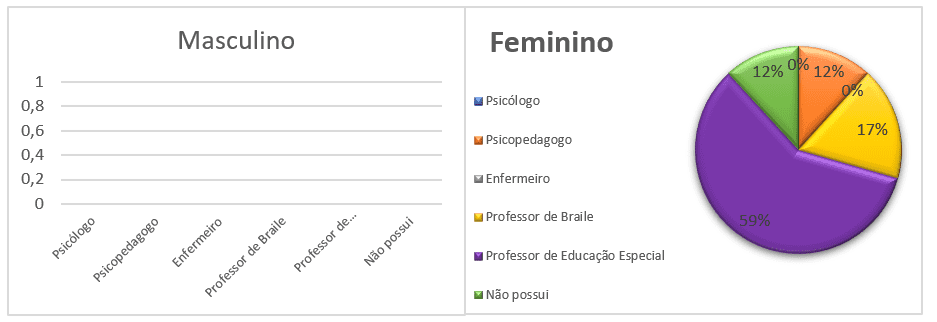

Figure 28 – Distribution according to the offer of professionals in the school

Source: Prepared by the author (2020).

According to the offer of professionals at school, it is observed that more than half (59%) has the special education professional for the training of the special student, followed by the Braille teacher (17%) for the visually impaired and, finally, psychopedagogist (12%). Despite the low rates of qualified professionals in meeting the special needs of students, this situation is in accordance with the recommendations of Law 13,146 that establishes training and availability of teachers for specialized educational care, translators and interpreters of Libras, interpreter guides and support professionals. (BRASIL, 2015). In addition, it is worth emphasizing the importance of involving all agents who are part of their daily lives of the special student —teachers, other students, coordinators, principals and employees—who will be directly linked to the inclusion of the disabled student in the educational environment. (MARTINS, 2006). Therefore, educators should still be seeking resources necessary to meet the disabled student seeking to meet their needs through special means for guidance and support that they need in order to be equally entitled to learning. (BALSANELI et al., 2015).

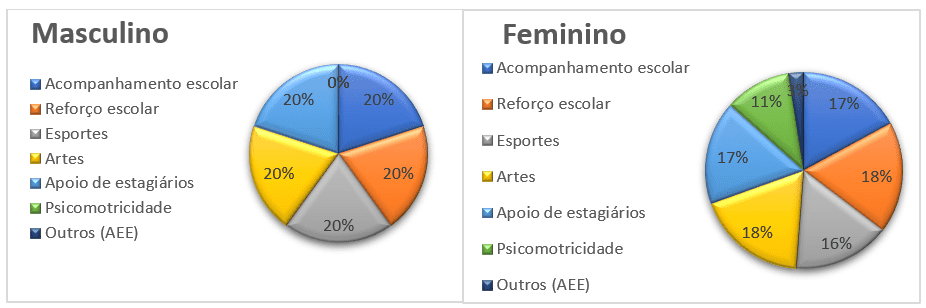

Graph 29 – Distribution of school activities aimed at special students

In the distribution of school activities (Graph 29), it is noted that in males the activities are equally practiced with the exception of psychomotricity (0%), while in females, it is revealed that greater practice of arts and school reinforcement (18%), besides greater contact with the area of psychomotricity (11%). Thus, as Vygotsky (1989) states, it is essential to focus on the potentialities of these subjects, stimulated – to explore the world, to interact with the other, to expose their opinion and desires, and that playful activities offer great opportunities for this. Thus, the learning possibilities of the student with special needs are increased, because, through these resources, he can fully experience teaching-learning situations, developing his creativity and expressiveness, interacting with other people, exercising cooperation and learning in groups. In Brazil, the document that governs the school inclusion process is the National Policy of Special Education from the perspective of Inclusive Education (2008), which aims to ensure the inclusion of students with disabled students, with global development disorders and high skills, in order to ensure their active participation throughout the learning process. (BRASIL, 2008). Moreover, the Brazilian Law for the Inclusion of Persons with Disabilities ensures that children and adolescents with any limitations are entitled, on equal terms, to games and recreational, sports and leisure activities in the school system, as well as to offer school support professionals for individualized and specialized follow-up. (BRASIL, 2015).

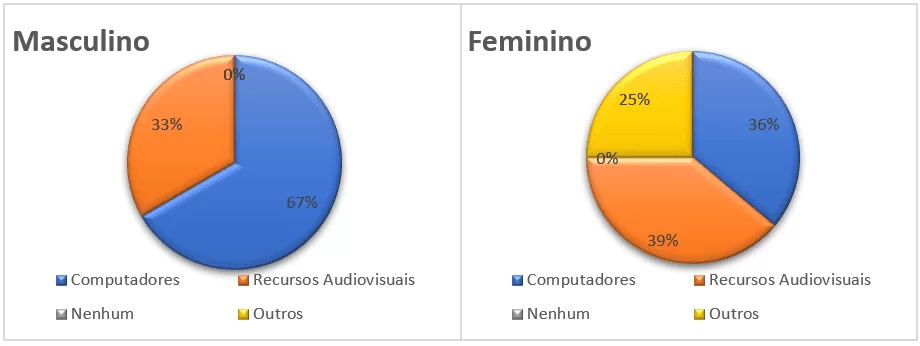

Figure 30 – Distribution of resources used for inclusion

From the analysis of the graph distribution of resources used for inclusion of students, it is evident that the use of computers and audiovisual resources prevails as a way to promote inclusion in school. Thus, assisted technology organizes and strengthens language, allowing effective communication and the acquisition of school and social skills, vital to ensure its full development and autonomy, to perform activities both at school and beyond. Therefore, it is necessary to guide and follow up the student at the time of the use of technological resources, with the intention, to help him/her adapt it. (HEIDRICH, 2003).

Graph 31 – Distribution according to the greatest difficulties of teachers in working with special students.

In view of the data in graph 31, it is noted that most of the participating teachers reported having as main challenge the lack of professional preparation (67% in males and 37% in females). In addition, difficulties such as lack of adequate materials, lack of multidisciplinary team, lack or scarcity of family follow-up, insecurity and lack of individualized care stand out.

With regard to professional training, the daily life of the classroom with students who have some kind of disability requires the teacher to train to mediate relationships, mobilize the concepts and organize the contents strategically, so that these students appropriate the knowledge systematized and made available by the school. (KONKEL et al., 2015). Added to this, most teachers have a functional view of teaching and everything that breaks with the practical work scheme they have learned and applied in their classrooms is initially rejected. (MONTOAN, 2003). Therefore, the presence of a student with special needs is not seen as something positive, but as a hindrance to the normal course of the room, being necessary, therefore, changes also in the representations and conceptions of teachers.

In addition, the structural and organizational elements of schools become real obstacles to teachers, even when they accept the challenge of educating all students. Thus, the scarcity of material resources, absence of auxiliary teachers, numerous classes and the multiplicity of disabilities present in the classroom are some of the factors that prevent the progress of the process of inclusion and full learning. (DUEK, 2007). In this context, the need for smaller classes is highlighted, since special students need a directed and constant attention to achieve full neuropsychosocial development. With this, it is perceived that we are immersed in a rudimentary and outdated educational structure that is based on a single way of teaching, implying that all students absorb the content unanimously.

Even professionals who face pedagogical renewal in their work, when they perceive the lack of resources, see themselves divided between what they do and what they would like to do in their practice. This distance between practical and desired work translates into suspicion of the new, which generates feelings of inadequacy and insecurity. (SOBRINHO, 2002).

However, inclusion is not restricted to the school environment, it requires engagement and planning, extrapolating the limits of the school and reaching the families of these students and social institutions in general, making it necessary to guide the school community and establish an effective relationship between the school and the family. (MARTINS, 2003). It is understood, therefore, that the inclusion of children with special educational needs begins long before their enrollment in school, still within the family. The school has the function of encouraging the participation of the family in educational activities, assuming the place of co-participant and co-responsible for this process.

Day Three:

In the third meeting, the initial idea was a conversation wheel between the teachers of the school Prof. Maria Martins and Lourenço, students of the 8th Period of the pedagogy course of the University Center of Votuporanga and the director responsible for the APAE of Votuporanga. However, due to the workload and curriculum of the students of the college, unfortunately, there was no possibility of their participation in the meeting. Therefore, this occurred only with the teachers and the director of the APAE.

During the discussion, topics such as the importance of educational preparation to meet the demands of students with special needs, the different forms of pedagogical approach to optimize the learning of these children, the warning signs and the need for referral to specialized educational centers and the possible professionals capable of assisting the teacher in the education process were addressed. During the meeting, the professionals were very interested and asked questions pertinent to each subject, in addition to adding reports of experience of their daily lives with special students,

This exchange of knowledge is extremely important for teachers, given that the 2018 School Census indicated the enrollment of 1.2 million people with special needs in regular schools in the country, which is an increase of 33.2% compared to 2014. (INEP, 2018). Therefore, it is relevant that professionals in the area know the different types of disability, in addition to clarifying their doubts, in order to enhance the possibilities of social and school inclusion.

5. CONCLUSION

It is concluded, therefore, that the objectives of this work were achieved, because it was possible to analyze the learning needs of teachers and trainees in the education process of children with special educational needs.

From the perspective of special education, Brazil has several laws and agendas that institute the inclusion of children and adolescents in different conditions as a form of coverage for their social insertion. However, the present project showed that the school insertion of students with special needs goes beyond complying with public policies and legislation, being of utmost importance the training of those who work in the area, in order to provide a quality and equal education to all and to break the social stigmas on the subject.

Thus, it is necessary a joint work between the areas of education and health, in which the former promotes a quality and appropriate education according to the demand of each special student, aiming and integral formation of the individual in all its potential; and the second performs an early diagnosis and appropriate treatment of each disease in order to reduce the negative impacts on the child’s development.

In addition, it is indispensable that the various spheres of education in the Government (Ministry of Education, State Secretaries of Education and Municipal Secretaries of Education) act promoting classes, courses, social and professional training to teachers and students in special education, as well as debates on the subject, aiming at the end of stereotypes, fears and prejudices for these students. Only in this way will education be more than egalitarian, it will be equitable.

6. REFERENCES

AMARAL, Lígia Assumpção. Resgatando o passado: deficiência como figura e vida como fundo. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo, 2004.

BALSANELI, Heloisa Monteiro; TREVISO, Vanessa Cristina. Crianças com deficiência visual e o braile. Cadernos de Educação: Ensino e Sociedade, Bebedouro, v.2, p. 155-168, 2015.

BLOS, Peter. Adolescência: Uma interpretação psicanalítica. São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1998.

BOURDIEU, Pierre. A escola conservadora: as desigualdades frente à escola e à cultura. In: NOGUEIRA, Maria Alice.; CATANI, Alfredo. (Orgs.). Escritos de educação. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1998. p. 39-64.

BRASIL. [Constituição (1988)]. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. Brasília, DF: Presidência da República. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicaocompilado.htm. Acesso em: 30 out. 2019

BRASIL. Declaração de Salamanca e linha de ação sobre necessidades educativas especiais. Brasília: UNESCO, 1994.

BRASIL. Decreto nº 1.130, de 05 de agosto de 2015. Institui a Política Nacional de Atenção Integral à Saúde da Criança (PNAISC) no âmbito do Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS). Brasília, DF: Ministério da Saúde, [2015]. Disponível em: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/gm/2015/prt1130_05_08_2015.html. Acesso em: 14 out. 2019.

BRASIL. Decreto nº 3. 298, de 20 de dezembro de 1999. Institui a Política Nacional para a Integração da Pessoa Portadora de Deficiência. Brasília, DF: Presidência da República, [1999]. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto/D3298.htm. Acesso em: 30 out. 2019

BRASIL. Decreto nº 6.286, de 5 de dezembro de 2007. Institui o Programa Saúde na Escola – PSE e dá outras providências. Brasília: Presidência da República, [2007]. Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/index.php?option=com_docman&view=download&alias=1726-saudenaescola-decreto6286-pdf&category_slug=documentos-pdf&Itemid=30192. Acesso em: 16 out. 2019

BRASIL. Decreto nº 7.611, de 17 de novembro de 2011. Dispõe sobre a educação especial, o atendimento educacional especializado e dá outras providências. Brasília, DF: Presidência da República, [2011]. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_Ato2011-2014/2011/Decreto/D7611.htm. Acesso em: 16 out. 2019.

BRASIL. Lei nº 8080, de 19 de setembro de 1990. Dispõe sobre as condições para a promoção, proteção e recuperação da saúde, a organização e o funcionamento dos serviços correspondentes e dá outras providências. Brasília, DF: Presidência da República, [1990]. Disponível em: https://bit.ly/332NgzQ. Acesso em: 30 out. 2019

BRASIL. Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezebro de 1996. Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Brasília, DF: Presidência da República, [1996]. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9394.htm. Acesso em: 18 out. 2019

BRASIL. Lei n° 12.796, de 04 de abril de 2013. Altera a Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996, que estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional, para dispor sobre a formação dos profissionais da educação e dar outras providências. Brasília, DF: Presidência da República, [2013]. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2011-2014/2013/lei/l12796.htm. Acesso em: 22 out. 2019

BRASIL. Lei nº 13.146, de 06 de julho de 2015. Institui a Lei Brasileira de Inclusão da Pessoa com Deficiência (Estatuto da Pessoa com Deficiência). Brasília, DF: Presidência da República, [2015]. Disponível em: http://www.punf.uff.br/inclusao/images/leis/lei_13146.pdf. Acesso em: 26 out. 2019.

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Documento subsidiário à política de inclusão. Brasília: Secretaria de Educação Especial, [2005]. p. 48.

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Política Nacional de Educação Especial na Perspectiva da Educação Inclusiva. Brasília: MEC/SECADI, [2008]. Disponível em: https://bit.ly/2KtcEIP. Acesso em: 24 out. 2019.

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Saberes e práticas da inclusão. Dificuldades acentuadas de aprendizagem e deficiência múltipla. Brasília: Secretaria da Educação Especial, [2006]. Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/seesp/arquivos/pdf/deficienciamultipla.pdf. Acesso em: 18 out. 2019.

BUENO, José Geraldo Silveira. Crianças com necessidades educativas especiais, política educacional e a formação de professores: generalistas ou especialistas? Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial, Curitiba, v.3, n. 5, p. 7-25, 2009.

CABRAL, Cristiane Soares; MARIN, Angela Helena. Inclusão escolar de crianças com transtorno do espectro autista: uma revisão sistemática da literatura. Educação em revista, Belo Horizonte, v.1, n. 33, p. 1-30, 2017. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0102982017000100113&lng=en&nrm=iso Acesso em: 19 out. 2019

CURY, Carlos Roberto Jamil. Políticas inclusivas e compensatórias na educação básica. Caderno de Pesquisa, São Paulo, vol.35, n.124, p. 11-32, 2005.

DE LIMA, Tatiana. Processo de inclusão de alunos com transtorno de déficit de atenção e hiperatividade. In: ENCONTRO REGIONAL DE HISTÓRIA, XIV., 2014, Paraná. Anais… Paraná: Unespar, 2014. p. 2436 – 2448.

DUEK, Viviane Preichardt. Professores diante da inclusão: superando desafios. In: CONGRESSO BRASILEIRO MULTIDISCIPLINAR DE EDUCAÇÃO ESPECIAL, IV., 2007, Londrina. Anais… Londrina: UEL, 2007. p. 1-8. Disponível em: http://www.uel.br/eventos/congressomultidisciplinar/pages/arquivos/anais/2007/066.pdf. Acesso em: 11 nov. 2019.

EDlER, Rosita. Removendo barreiras para aprendizagem: educação inclusiva. Porto Alegre: Mediação, 2000.

ESPANHA. Declaração de Salamanca sobre princípios, políticas e práticas na área das necessidades educativas especiais. Salamanca: 1994.

FARIA, Paula Maria Ferreira de; CAMARGO, Denise de. As Emoções do Professor Frente ao processo de Inclusão Escolar: uma Revisão Sistemática. Revista brasileira de educação especial, Bauru, v. 24, n. 2, p. 217-228, abr. 2018. Disponível em: https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-65382018000200217. Acesso em: 30 out. 2019

FERRAIOLI, Suzannah.; HARRIS, Sandra. Effective educational inclusion of students on the autism spectrum. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, v. 41, n. 1, p. 19-28, 2011.

FERREIRA, Windyz. Educação Inclusiva: será que sou a favor ou contra uma escola de qualidade para todos? Revista da Educação Especial, Brasília, v. 2, n. 23, p. 40-46, 2005.

FREITAS, Luiz. Carlos. A internalização da exclusão. Educação & Sociedade, Campinas, v. 23, n. 80, p. 299-325, set. 2002.

GRAEFF, Rodrigo Linck; VAZ, Cícero. Avaliação e diagnóstico do transtorno de déficit de atenção e hiperatividade (TDAH). Psicologia USP, São Paulo, v. 19, n. 3, p. 341-361, set. 2008. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S010365642008000300005&lng=en&nrm=iso. Acesso em: 17 out. 2019.

HEIDRICH, Regina de Oliveira; SANTAROSA, Lucila Costi. Novas tecnologias como apoio ao processo de inclusão escolar. CINTED-UFRGS, Rio Grande do Sul, v.1, n.1, p.1-10, 2003. Disponível em: https://seer.ufrgs.br/renote/article/download/13638/7717. Acesso em: 25 out. 2019

HONNEF, Cláucia. O desafio da formação docente frente à educação inclusiva. Revista Tempos e Espaços em Educação, São Cristóvão, v. 04, n. 6, p. 135-146, jan./jun. 2011.

IBGE – INSTITUTO BRASILEIRO DE GEOGRAFIA E ESTATÍSTICA. Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios: população residente, por sexo e grupos de idade, segundo as Grandes Regiões e as Unidades da Federação 2010. Rio de Janeiro. 2010. Disponível em: https://censo2010.ibge.gov.br/sinopse/index.php?dados=12. Acesso em: 12 out. 2019

INEP – INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTUDOS E PESQUISAS EDUCACIONAIS ANÍSIO TEIXEIRA. Censo Escolar 2018 revela crescimento de 18% nas matrículas em tempo integral no ensino médio. Brasília, DF. 2018. Disponível em: http://portal.inep.gov.br/artigo/-/asset_publisher/b4aqv9zfy7bv/content/censo-escolar-2018-revela-crescimento-de-18-nas-matriculas-em-tempo-integral-no-ensino-medio/21206. Acesso em: 29 out. 2019.

KONKEL, Eliane Nilsen; ANDRADE, Cleudane; KOSVOSKI, Deysi Maia Clair. As dificuldades no processo de inclusão educacional no ensino regular: a visão dos professores do ensino fundamental. CONGRESSO NACIONAL DE EDUCAÇÃO, XII., Paraná, 2015. Anais… Paraná: Educere, 2015. p. 5776-5790. Disponível em: https://educere.bruc.com.br/arquivo/pdf2015/19144_8387.pdf. Acesso em: 30 out. 2019

LACERDA, Cristina Broglia Feitosa de. A inclusão escolar de alunos surdos: o que dizem alunos, professores e intérpretes sobre esta experiência. Cad. CEDES., Campinas, v. 26, n. 69, p. 163-184, 2006.

LOURO, Guacira Lopes. Gênero, sexualidade e educação: uma perspectiva pós estruturalista. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1997.

MANTOAN, Maria Teresa Eglér. Inclusão escolar: o que é? Porque é? Como fazer? São Paulo: Moderna, 2003.

MARTINS, Lúcia de Araújo Ramos. A inclusão escolar do portador da síndrome de Down: o que pensam os educadores? Natal: EDUFRN, 2003.

MARTINS, Lúcia de Araújo Ramos. Formação professores numa perspectiva inclusiva: algumas constatações. In: MANZINI, E.J. (Org) Inclusão e Acessibilidade. Marilia: ABPPE, 2006. Disponível em: http://seer.fclar.unesp.br/iberoamericana/article/viewFile/5375/4308. Acesso em: 27 out. 2019.

MAZZOTTA, Marcos José. Trabalho docente e formação de professores de educação especial. São Paulo: EPU, 1993.

MAZZOTTA, Marcos José. Educação especial no Brasil: história e políticas públicas. 5. ed.. São Paulo: Cortez, 2005

MELO, Francisco Ricardo Lins Vieira de; PEREIRA, Ana Paula Medeiros. Inclusão escolar do aluno com deficiência física: visão dos professores acerca da colaboração do fisioterapeuta. Revista brasileira de educação especial, Marília, v. 19, n. 1, p. 93-106, mar. 2013. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-65382013000100007&lng=en&nrm=iso. Acesso em: 15 out. 2019.

MITTLER, Petter. Educação inclusiva: contextos sociais. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2003.

MONTILHA, Rita de Cassia Ietto et al. Percepções de escolares com deficiência visual em relação ao seu processo de escolarização. Paidéia, Ribeirão Preto, v. 19, n. 44, p. 333-339, dez. 2009. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0103-863X2009000300007&lng=en&nrm=iso. Acesso em: 26 out. 2019.

NUNES SOBRINHO, Franciso de Paula. O stress do professor do ensino fundamental: o enfoque da ergonomia. In: LIPP, Marilda. (Org.). O stress do professor. Campinas: Papirus, 2002. p. 81-94.

NUNES, Sylvia da Silveira; SAIA, Ana Lucia; TAVARES, Rosana Elizete. Educação Inclusiva: Entre a História, os Preconceitos, a Escola e a Família. Psicologia: ciência e profissão, Brasília, v. 35, n. 4, p. 1106-1119, dez. 2015. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S141498932015000401106&lng=en&nrm=iso. Acesso em: 28 out. 2019

PASTURA, Giuseppe; MATTOS, Paulo; ARAÚJO, Alexandra. Prevalência do transtorno do déficit de atenção e hiperatividade e suas comorbidades em uma amostra de escolares. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria, São Paulo, v. 65, n. 4, p. 1078-1083, 2007. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0004-282X2007000600033. Acesso em: 22 out. 2019

PLETSCH, Márcia Denise. A formação de professores para a educação inclusiva: legislação, diretrizes políticas e resultados de pesquisas. Educar em revista, Curitiba, n.33, p.143-156, 2009. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0104-40602009000100010&lng=en&nrm=iso. Acesso em: 26 out. 2019

SANCHES, Antonio Carlos Gonsales; OLIVEIRA, Márcia Aparecida Ferreira de. Educação inclusiva e alunos com transtorno mental: um desafio interdisciplinar. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, Brasília, v. 27, n. 4, p. 411-418, dez. 2011. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S010237722011000400004&lng=en&nrm=iso. Acesso em: 28 out. 2019.

SANT’ANA, Izabella Mendes. Educação inclusiva: concepções de professores e diretores. Psicologia em Estudo, Maringá, v. 10, n. 2, p. 411-418, mai/ago. 2005.

SANTOS, Daísy Cléia Oliveira dos. Potenciais dificuldades e facilidades na educação de alunos com deficiência intelectual. Educação e Pesquisa, São Paulo, v. 38, n. 4, p. 935-948, dez. 2012. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S151797022012000400010&lng=en&nrm=iso. Acesso em: 19 out. 2019

SKINNER. B. F. (1972). Tecnologia do Ensino. Tradução organizada por R. Azzi. São Paulo: EPU (trabalho original publicado em 1957).

SKLIAR, C. Educação e exclusão: abordagem sócio-antropológicas em educação especial. Porto Alegre: Mediação, 1997.

SOUSA, Priscila Batista de; SÁ-LIMA, Mariana Araguaia de Castro; VALVERDE, Clodoaldo. A inclusão escolar de alunos com Síndrome de Down na última década. Pedagogia em Foco, Iturama, v. 12, n. 8, p. 44-60, jul./dez. 2017. Disponível em: https://revista.facfama.edu.br/index.php/PedF/article/view/316/. Acesso em: 13 out. 2019.

THESING, Maria Luzia; COSTAS, Fabiane Adela. As proposições de uma escola inclusiva na concepção de professores de educação especial: algumas problematizações. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Pedagógicos, Brasília, v. 99, n. 252, p. 277-293, ago. 2018. Disponível em: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S217666812018000200277&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=pt. Acesso em: 25 out. 2019.

VIANNA, Cláudia. Contribuições do conceito de gênero para a análise da feminização do magistério no Brasil. In: CAMPOS, Maria Christina Siqueira de Souza; SILVA, Vera Lúcia (orgs.) Feminização do magistério: vestígios do passado que marcam o presente. Bragança Paulista: Edusf, 2002. p.39-67.

VYGOTSKY, Marta Kohl de. Aprendizado e desenvolvimento: um processo sócio histórico. São Paulo: Scipione, 1993.

7. APPENDIX

APPENDIX A – Questionnaire for Trainees of the Pedagogy Course of UNIFEV and for Teachers of the Municipal School Researched

How old are you? _____________.

Gender:

- Does the school where you operate have special students?

- If so, what is the profile of this student with special needs?

![]() Other pathologies. Which(s)? ____________________________.

Other pathologies. Which(s)? ____________________________.

2. Have you ever had the opportunity to prepare for special education through curricular or extracurricular activities? (Specify whether it was offered by the institution)

______________________________________________________________________.

3. Have you ever had the opportunity to work with a special student? If so, what are the difficulties encountered in promoting educational activities?

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________.

4. Is the school you work on adapted to receive special students?

5. If the answer to the above question is no, what should be incremented? (you can check more than one option)

![]() Others:_______________________.

Others:_______________________.

6. Do you encounter resistance from other education professionals in working with special students?

7. If the answer to the above question is yes, what types of resistance do you consider to exist? (You can check more than one option)

![]() Lack of preparation opportunity

Lack of preparation opportunity

![]() Others:________________________.

Others:________________________.

8. In the school you work in, you have aspecialized professional

![]() Others:________________________.

Others:________________________.

9. What activities are carried out at the school where you operate?

![]() Others:________________________.

Others:________________________.

10. What resources are used for inclusion?

![]() Others:________________________.

Others:________________________.

11. Comment on the greatest difficulties encountered to work with a special student (at the moment) and if you come to work in the future.

[1] Graduating from the 5th period of the medical course of the University Center of Votuporanga.

[2] Graduating from the 5th period of the medical course of the University Center of Votuporanga.

[3] Graduating from the 5th period of the medical course of the University Center of Votuporanga.

[4] Graduating from the 5th period of the medical course of the University Center of Votuporanga.

[5] Graduating from the 5th period of the medical course of the University Center of Votuporanga.

[6] Graduating from the 5th period of the medical course of the University Center of Votuporanga.

[7] Advisor. Master of the undergraduate course of Medicine at the University Center of Votuporanga.

Submitted: September, 2020.

Approved: November, 2020.