ORIGINAL ARTICLE

FELIPPE, Gibran [1], ZOTES, Luís Pérez [2]

FELIPPE, Gibran. ZOTES, Luís Pérez. Future of the national financial market: Moment of innovation by FinTechs in transformation to the national banking environment. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 05, Ed. 10, Vol. 07, pp. 31-62. October 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access Link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/accounting/financial-market, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/accounting/financial-market

SUMMARY

The Brazilian banking system is in a stage of maturity conducive to the receipt of a new entrant that, following the global trend, are FinTechs[3]. In this way, these companies that use technology to provide financial services, are beginning to impact the national financial market, bringing with it potential to shake the results of the country’s large financial corporations. This article has a broad overview of the concentration of the national banking market, compared to global standards, as well as the dimensioning of opportunity for new entrants through technologies established by startups[4], in an irreversible process in terms of innovation. The methodology used here was based on a broad literature review resulting in the identification and consequences of the main impacts of this new financial order, in which size is no longer so relevant, given the implementation of new practices for a constantly renewed spectrum of clients. New entrants to the financial market should be truly customer-centric, agile and able to adapt to a rapidly changing environment, skilled at working with companies in a complex ecosystem of partnerships and markets. They should seek excellence in data analysis, dynamic pricing and the construction of technologies that allow new functionalities to be developed and implemented. New needs, practical, without the bank status symbols.

Keywords: Innovation, FinTechs, startups, banking market, information technology.

1. INTRODUCTION

The term FinTech can be broadly defined as technologically enabled financial innovation, which can result in new business models, applications, processes or products with an associated material effect on financial markets, financial institutions and financial services (CARNEY, 2017). FinTech innovations are emerging in many facets of finance – retail and wholesale payments, financial market infrastructure, investment management, insurance, credit provision and capital increase. In the near future, such applications may be used, including in capital market operations (MOULES, 2014).

This article focuses on the evolution of FinTechs regarding the potential for penetration, use and its consequences for the national financial market. In doing so, it complements a number of other studies recently released or prepared by official bodies on other aspects of FinTechs, in view of the numerous discussions on the subject and the need for regulation by the BACEN in an extremely concentrated financial environment. In Brazil, the credit and payments market are the driving springs until then, generating significant interest among financial policymakers and the general public.

Still on the credit aspect, some analysts suggested that the innovations established by FinTechs could transform lending markets by reducing costs, improving the customer experience and improving credit risk assessments. This aspect is not only a recitation, with beginning, middle and end, but simply a movement that, once started, will become dynamic and permanent, definitively changing traditional banking relations. An alternative view holds that FinTechs’ future credit growth may be limited by business models vulnerable to changing financial conditions (MILNE, 2016). This fact is relevant, since the country has not yet been able to create effective devices against credit risks.

The motivating question for the context present in this study is: “Why is Brazil different from other markets?”. Although financial disruption has proved to be a common trend in many countries, it is believed that the Brazilian financial system is particularly complex. The banking market is focused on global standards, and penetration, by most metrics, is below developed countries, especially in the lower income classes. Prices for financial services and loan spreads[5] are also among the highest in the world.

In this peculiar market structure, companies that want positioning suffer a greater impact in Brazil than in other developed markets, leading to several questions, noddedly understanding why FinTechs become relevant only now. The answer lies in the expansion of the technological base worldwide, changing the profile of the consumer market, in addition to the need for service at a scale.

Several trends are converging, which will likely increase the relevance of FinTechs. Another point observed is the recent mergers, which have further concentrated the financial system, increasing the need for new entrants. Smartphones and internet access, key delivery mechanisms for information technology, are also rapidly increasing as Brazil’s generation of advanced technology reaches maturity. Therefore, FinTechs present themselves as solutions to meet the demand, taking into account this scenario.

According to a recent study by the Equity Research[6] team of investment bank Goldman Sachs, a potential revenue of R$ 75 billion in 10 years was evidenced for the more than two hundred FinTechs, currently operating in Brazil. Also in the observation of the Goldman Sachs report, one can see the low level of global internet connection in South America, facing the Asian continent, 10.4% anti 49.7% of total global users.

Therefore, there is a clear need for response on the part of large Brazilian banks, elaborating or even copying disruptive products in need of large investments and network training in IT for greater operational efficiency.

Business environments have undergone constant changes due to globalization and fierce competition for space in the market. The sustainability and competitiveness of a given company (public or private) also depends on the quality of its products or services and its potential to meet demand. In this environment, the article studies the national lag, its need for a strong dosage, paraphrasing medicine, streptomycin to quickly get out of the lethargy of large institutions and increase the potential for innovation and diversification of the services offered, otherwise the lapse in terms of efficiency will punish those who have not seen the new opportunities unveiled in other markets.

2. THEORETICAL FOUNDATION

2.1 CONJUNCTURE FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF FINTECHS IN BRAZIL

Fintechs, according to Buchak (2017) are companies that use technology to provide financial services. The emergence of Brazilian FinTechs did not follow at the same speed observed in other countries of the world, in fact, are still beginning to emerge in Brazil. They are stimulated by increasingly favorable conditions, which should make them progressively more relevant to investors with a focus on the financial sector. It is possible to anticipate transition, because it will be different from those in more developed markets and through this starting point, the market itself will adjust and respond to this movement.

Another widely accepted definition for the term FinTech is established by Carney (2017) as technologically enabled financial innovation, which can result in new business models, applications, processes or products with an associated material effect on financial markets, financial institutions and financial services. FinTech’s innovations are emerging in many facets of finance, including:

- Retail and wholesale payments;

- Financial market infrastructures;

- Investment management;

- Insurance;

- Provision of credit;

- Capital increase.

This article focuses on the provision and housing of FinTechs, not taking into account, projects still in progress. In doing so, it complements a number of other studies recently released or being prepared by official bodies on other aspects of FinTechs. The technology involved in the development of FinTechs has generated significant interest in financial markets, policymakers and the general public. Some analysts suggested that innovations could transform financial markets by reducing costs, improving the customer experience and improving credit risk and payment assessments.

An alternative view (DE ROURE, 2016) holds that FinTechs’ future credit growth may be limited by business models vulnerable to changing financial conditions due to consumer and investor protection considerations. This article delimits the vision and understanding of the functioning of FinTechs credit markets in Brazil, including the size, scope and growth of these activities. It also assesses the potential microfinancial benefits and risks of these activities and considers the possible implications for financial stability in case the broad use of this technology grows to the point of representing a significant portion of the total operations in the national financial market.

For the purposes of this study, the term FinTech encompasses all financial activity facilitated by electronic platforms by which users are directly married to creditors.

When based on credit activities, such communities are referred to as loan-based crowdfunders[7], “peer-to-peer[8] (P2P) lenders, or “market lenders.” These electronic platforms can facilitate a number of financial transactions, including secured and unsecured loans, debt-free financing, such as invoice financing, means of payment, etc. In addition, some electronic platforms go beyond a P2P matching business model using their own balance sheet for financial activities.

In Brazil, as in other countries of the world, the emergence of FinTechs is not a simple thing to measure in terms of impact on the usual dynamics of the financial market. The five largest banks in Brazil (excluding development banks) hold 84% of the total loans in the system.

The impact of the disruption on any market depends largely on the shape of that market. In Brazil, we see the conditions in place for technology-driven disruption to have a greater impact than in some developed markets. Therefore, certain conspicuous evaluations objectively reveal the following assumptions in the national environment:

- The Herfindahl Hirschman[9] market concentration index for Brazil is in the upper half of the range when compared to markets in other countries. This concentration is particularly evident in bank branches, where the top five banks have 90% of the branches. With the traditional distribution of financial services being interrupted by new technologies, knocking down barriers to entry;

- Limited penetration, especially at low income. The penetration of banking services in Brazil is low compared to global standards, although relatively close to peers in the same region and at the same level of development. Barriers to penetration resulting from culture, regulation and market structure are identified, all of which could be overcome by the penetration of technology and by aging and evolution in the use of new banking tools by the population;

- Expensive prices for loans as well as other financial services. Interest rates on loans in Brazil are among the highest in the world, just as service rates are also expensive compared to those charged by banks for similar services in other countries with the same vicissitudes. Much of this problem lies in limiting information, which increases risk and reduces incentives for new competitions. Thus, new technologies contribute to the expansion of the price outlet available to bank customers and potential participants, which ends up driving prices down.

The impact of the rupture in any market depends largely on the conjuncture structure of forces operating in this competitive environment. In Brazil, the conditions in force for technology-driven disruption to have a greater impact than in some developed markets are observed. Therefore, certain conspicuous evaluations objectively reveal the following assumptions in the national environment:

Figure 1 – Map of the FinTechrevolution in Brazil.

- Increasing smartphone and internet penetration: number of internet users in Brazil has grown 11% per year since 2003 (compared to an overall average rate of 9%). At the same time, in 2015, 86% of Brazilian adults had a mobile phone, up from 73% in 2010, with 48% of all mobile phones considered smartphones, up from 19% in 2013. With many of the financial technology platforms using smartphones as the delivery method of their services, the continued expansion in penetration is blunt;

- Expanding demographic bonus: The average age of the population in Brazil is increasing, as the demographic bonus of the 1990s continues to age. As this generation enters its most productive and cash-generating years, it must also become more frequent users of financial services. At the same time, this generation is more educated and more technologically inclined than previous generations, which contributes to the acceptance of Fintechs solutions based on the Internet and mobile devices;

- Recovering economy: The Brazilian economy has contracted in real terms in the last three years, but is now emerging from recession. While investment and interest in new technologies were discontinued during the recession, these topics are expected to play a more prominent role as the economy recovers. Greater wealth should lead to more demand for solutions to manage, intermediate and deploy wealth.

2.2 MAIN OPERATIONS OF FINTECHS IN BRAZIL

It is observed in the country, day after day, the emergence of FinTtechs of all shapes and sizes with different associations. According to a recent presentation by Insper[10] Educacional, taught to employees of the operations desk of a large treasury (name of the institution protected due to strategies not authorized for public disclosure) in the country, there are approximately 210 different FinTechs in Brazil, the largest number in Latin America (2018 data). For the most part, these companies are located in the State of São Paulo and operate exclusively in Brazil (Figure 1 illustrates some of them) although the main technology used is quite mixed, as are end customers. It is estimated that these companies are achieving a total revenue of R$ 75 billion over 10 years, in various market niches.

According to IAIS[11] (2017), some assumptions are relevant for the research of operations of this nature in a competitive financial environment, something fully feasible and adjustable to the national market, among them: (i) data on FinTech’s credit activity of academic studies and private sector providers; (ii) publicly available data from the platforms; (iii) studies by the public, academic and private sector on the FinTech credit sector, considered to be relevant sources directly linked to the existing work of member clearing institutions and (iv) an overview of current regulatory structures and other policies established for the operationalization of FinTechs.

The availability and quality of the data may require greater attention as FinTech’s credit markets develop, so it is important to stress that it is not teutonic observation, with maximum accuracy and without deviations. This is probably the main gap in Brazil for the appropriate regulation and standardization of the market by the monetary authority.

In this context, two institutions present themselves prominently, among which are: NuBank, a successful credit card company that uses technology to identify and capture customers and Banco Original, a major pillar of all-digital operations on proprietary platforms.

One of FinTechs’ main operations refers to credit activity facilitated by electronic platforms. This usually involves borrowers being corresponded directly with investors, although some platforms use their own balance sheet to lend (DELOITTE, 2016). FinTech platforms facilitate various forms of credit, such as loans to consumers and businesses, loans against real estate, and unsecured debt financing, such as invoice financing, as shown in Table 1:

Table 1 – Fintechs spread across various niches and industries. A potential revenue margin of R$ 75 billion was identified.

| AREA | Logic | POTENTIAL REVENUES IN 10 YEARS (R$ BILLION / YEAR) | COMPANIES IN BRAZIL | |

| Banking |

The Brazilian banking market is highly concentrated, which increases costs and limits penetration. Regulation and technology are breaking down distribution-related barriers to entry, paving the way for new entrants who can reduce asset and liability spreads and increase penetration. The model would extend from full-service virtual banks to simple e-wallets | 50 |

|

|

| Payments |

Although Brazil is in one of the most developed markets in Latin America, the Brazilian payment system is concentrated and offers limited functionality, given the older technology. New entrants take advantage of the latest technology in acquisition, payment processing and money transfers, with solutions in the P2P and B2B spaces. | 12 |

|

|

| Personal Finance Management |

Brazilians historically have limited tools to manage personal finances, which has led to increased use of expensive loans and low allocation of resources. Companies are using Internet-based solutions to help users manage accounts and renegotiate loans, as well as provide markets for new loans and savings products. | 6 |

|

|

| Lending |

The average annual rate of loans in Brazil is 32%, but can reach 15% per month for certain personal loans. Part of this is driven by the limited amount of information that borrowers and lenders have about each other, as well as by deficiencies in distribution. Companies are using Internet-based and mobile-based platforms, along with innovative business models, to bridge the gap between savers and borrowers, both inside and outside the financial system. | 22 | NuBank, Geru, Nexoos, Credisphera, BKF Online | |

| Investments, Economics, Wealth Management, Trading |

Saving money in Brazil, particularly for the lower income strata, has been left to low-income retail banking products, resulting from limitations in distribution and information, as well as market concentration. Through easy-to-use online platforms, new companies offer customers alternatives to invest in fixed income and capital products, directly or indirectly, through comparison tools that highlight the advantages and disadvantages of each product. | 10 | Magnetis, Órama, SmartBrain, Investeapp, Verios, SmarttBot, Warren, Easynvest, Yubb, Fixed Income, My Ynvestiments, Control | |

| Safe |

The insurance sector in Brazil has modest penetration as a result of high levels of real interest rates as well as limited distribution. While new companies can’t combat the problems created by high interest rates, they seek customers through smart online distribution platforms and improve subscription efficiency using a combination of big data and traditional actuarial practices. | 25 | Bidu, Thinkseg |

Source: BANCO GOLDMAN SACHS (2017).

There is also variation in the lender base of FinTech’s credit platforms: some sources of financing are primarily from retail investors, while others use significant resources from institutional investors, banks, and securitization markets. Banks originate loans to FinTech credit platforms in several jurisdictions. The availability of official fintech credit data is limited, so most analyses of these markets are based on unofficial sector surveys and platform financial disclosures.

Academic research on loan volumes in 2015 shows considerable dispersion in the size of FinTech’s credit market in all jurisdictions, including the fledgling national market. In absolute terms, FinTech’s largest credit market is China, followed at a distance by the United States and the United Kingdom (compared to China, such a market deserves a special focus, to be covered in the next topic).

In general, FinTech’s credit is a small fraction of overall credit, but it appears to be growing rapidly and can have much larger stakes in specific market segments. For example, in the UK, FinTech’s credit was estimated at 14% of the equivalent flows of gross bank loans to small businesses in 2015, but only 1.4% of the open bank credit stock for consumers and small and medium-sized enterprises as of the end of 2016. Compared to traditional banks, the strong process digitization and specialized focus of FinTech credit platforms can reduce transaction costs and bring convenience to end users. It can also increase access to credit and investments for underserved segments of the population or the business sector. Despite these benefits, there are a number of potential vulnerabilities that can hinder future growth in the industry. The financial performance of the platforms could be substantially affected by fluctuations in investor confidence, given the loan models of national bank branches. Moreover, there is a need for P2P-type pairing so that typical operations of the national market can be safely transtraded on technology platforms, i.e., there is a need for remote access to bank data, including to avoid operational risks in case of absence at the limit available for higher volumes, or even blocking for fraudulent operations.

In addition, financial risk on platforms may be higher than in banks due to increased appetite for credit risk, untested risk processes, and relatively greater exposure to cyber risks. For financial stability, FinTech’s credit activity could present a number of benefits and risks if it grew to represent a significant portion of the total credit.

Potential benefits include access to alternative sources of financing in the economy. A lower concentration of credit in the traditional banking system could be useful in case there are idiosyncratic problems in banks. FinTech platforms can also pressure incumbent banks to be more efficient in their credit provision. At the same time, if FinTech’s credit reaches a significant portion of the credit markets, this can generate systemic risk concerns.

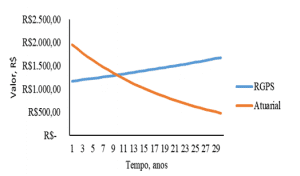

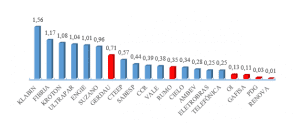

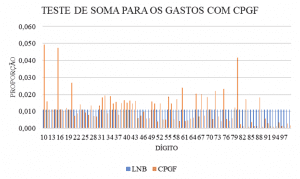

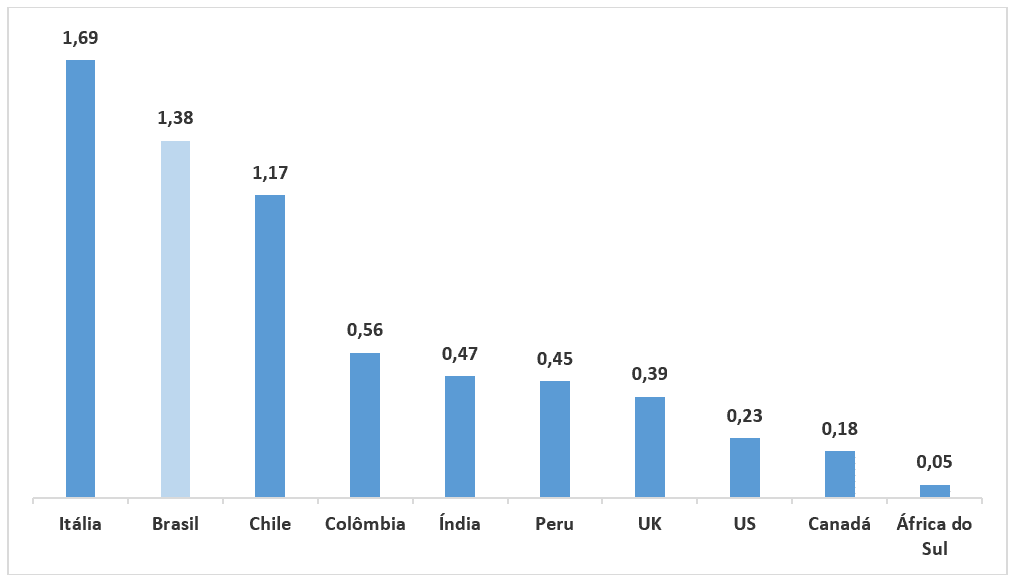

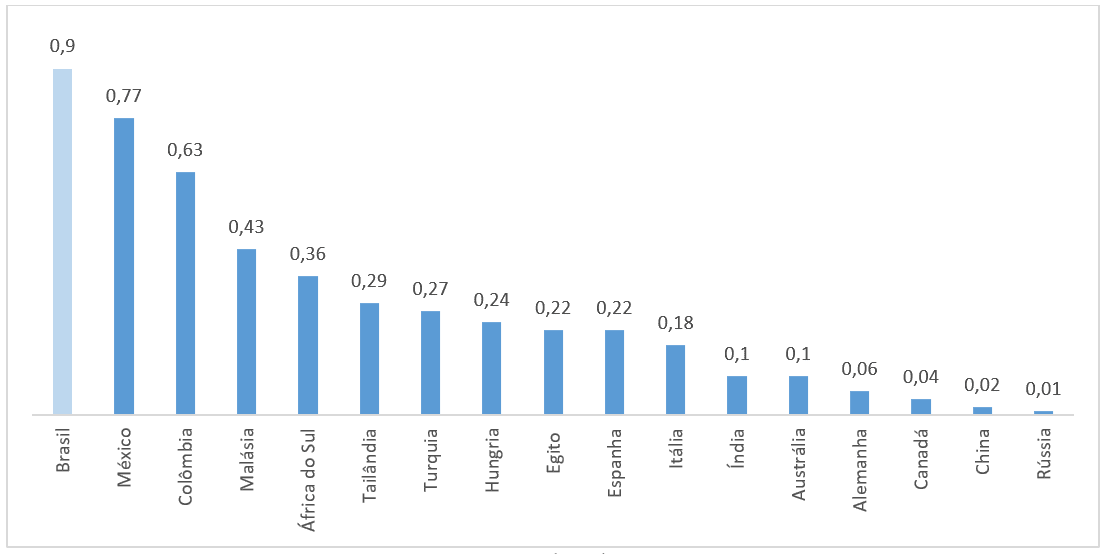

Some factors that contribute to increasing fintech’s credit-related financial inclusion may also reduce lending patterns in countries where credit markets are already deep. In addition, FinTech’s credit provision could be relatively pro-cyclical, taking into account the potential for a credit setback to certain parts of the economy because of the loss of investor confidence during periods of stress. Graph 1 presents an overview of comparative costs, highlighting the Brazilian position as one of the most expensive on the planet.

Figure 1 – Cost of loans in Brazil is one of the highest in the world. Loan rate and spread by country.

Incumbent banks may take on more credit risk in response to increased lending competition, while an abrupt erosion of their profitability may create broader difficulties for the financial system, given banks’ supply of a number of systemically important services. Finally, FinTech’s credit poses challenges to the regulatory perimeter and monitoring by credit activity authorities.

Also in relation to the national banking system, the following data are obtained in May 2017: 90% is the percentage of branches in Brazil belonging to the five main banks. The market has become more concentrated since the financial crisis: in 2007, the same statistic was 71%. Already 47% is the number of bank branches per 100,000 adults in 2015, making Brazil one of the most “branched” systems in the world. The branches are well used, however; Brazil has the largest share of the population reporting that it goes to a physical agency more than five times per quarter. 50% is the share of administrative banking expenses related to the operations of the branches.

Regarding the potential of the market it is said that: 50% against 12% is the interest rate that Brazilian banks charge on loans, versus the rate they offer to depositors of savings. The loan spread, which signals a high cost of borrowing and high cost of savings opportunity, is higher only in Malawi and Madagascar, according to a report by Goldman Sachs (2017). In addition to these aspects, 57% is the share of total loans that Brazilian government-owned banks kept at their peak (July 2016). This growth in stocks has put pressure on capital levels, which are lower in government banks than in private institutions.

FinTechs, in one way or another, have existed in Brazil for much of the last 10 years. As mentioned in the previous topics, some of the conditions of the Brazilian market, in particular the strong concentration of banking and other financial services in the hands of a small number of companies, create a favorable environment for the interruption, but they have also existed for some time.

In recent years, other factors have changed, which we see as creating a more receptive environment for disruption. First, the concentration in the banking system has increased. Second, the penetration of technology, especially smartphones, has increased to the point where the business models of several of FinTechs can reach critical mass, also benefiting from demographic data more open to change. Third, the slowdown in the economic cycle and the expected recovery in the coming years could create the opportunity for new companies to emerge and grow with economic activity. As shown in Graph 2, account maintenance rates in Brazil are higher than in other countries.

Figure 2 – Monthly account maintenance fee / GDP per capita 2015-2016.

There are specific reasons why rates and spreads in Brazil are higher. Much has to be done, as mentioned above, given regulation and taxes (particularly the latter), but others have to do with information or lack thereof.

Brazil has a negative credit agency (which identifies the bad behavior of non-payers, but does not follow the good behavior of payers), but efforts to develop a positive credit department (which would reduce risks and spreads) have been mixed so far.

No information is shared with potential participants, which limits competition, reducing the visibility of potential returns. The government is pressuring banks to reduce spreads, but it is possible that competition – stemming from disruptive technological advances that improve the flow of information, would probably be more successful.

In terms of the use of internet and smartphones, it is observed that the movement is still on the rise, as internet use in Brazil has increased for most of the last decade (the number of users has grown 11% since 2005), largely in line with global trends (CAGR[12] of 9% since 2005).

The number of internet users is above the global average, according to World Bank data, while broadband use for internet connection seems to be in line with the average. According to the Brazilian geography and statistics agency, IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics), internet use is higher at higher income levels than those with lower income and more prevalent among individuals with more years of study and between 15 and 34 years, considering internet use through a combination of desktop computers, mobile phones and tablets.

The penetration of mobile phones in Brazil is relatively high, with more mobile phones per capita than in the United States or the United Kingdom, according to the World Bank. The Pew Research Center noted that in 2015, 86% of Brazilian adults had a cell phone, compared with an average of 86% in 39 countries surveyed (and up from 73% in 2010).

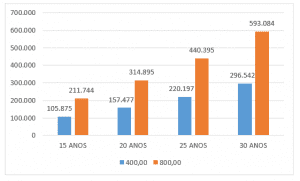

Also according to the Pew Research Center, 48% of all mobile phones in Brazil as of 2015 were considered smartphones, compared to 19% in 2013. This level of smartphone penetration is in line with the global average, but falls short of levels in developed markets. Also in terms of income distribution, the disparity in the costs of operations of Brazilian banks for customers is notorious, according to Graph 3.

Figure 3 – AVG bank fees / disposable income per capita X GNI coefficients.

In the national environment, the segments in which there is more financial technology activity are also examined. Over time, fintechs capture stake in a significant part of the financial services market, being one of the main drivers of growth and penetration, as well as an agent for reducing spreads and rates. Given the dynamics of the Brazilian market (concentration, penetration and price), such evolution has been happening differently from what has occurred in other markets, both developed and developing. Thus, the rise of FinTechs will likely spur incumbent banks to invest heavily in IT, reducing costs and improving efficiency.

2.3 ANALYSIS OF CHINESE BENCHMARKING

Before analyzing the Chinese market properly, it is important to list some relevant characteristics of that country, as well as the reason for this analysis, based on the direct correlation with Brazil, since the international financial markets historically consider Brazil and China as emerging countries and peers, however, as addressed by a recent report in The Economist magazine, China has distanced itself from Brazil towards developed countries , in which much of this aspect lies exactly in the technological gain of recent years.

According to Internet World Stats (2017), data is relevant to China, which is the second largest economy in the world:

- Territorial extension: 9,597,000 km² – 3rd largest in the world;

- Population: 1.379 billion inhabitants – the most populous country in the world;

- Number of Internet users: 705 million people (triple the number of active U.S. users, about 242 million people);

- In 2015, China raised $231 billion in venture funds, surpassing the U.S. in the total amount of venture capital invested;

- Investors put $19.3 billion in Asian companies versus $18.4 billion in U.S. companies in the second quarter of this year;

- Almost 15% of the adult population in China is engaged in some way with entrepreneurship and 11% of this group already manages an established business;

- In 2015, 12% of peking university graduates opened or worked in startups. In 2005, this number was only 4%;

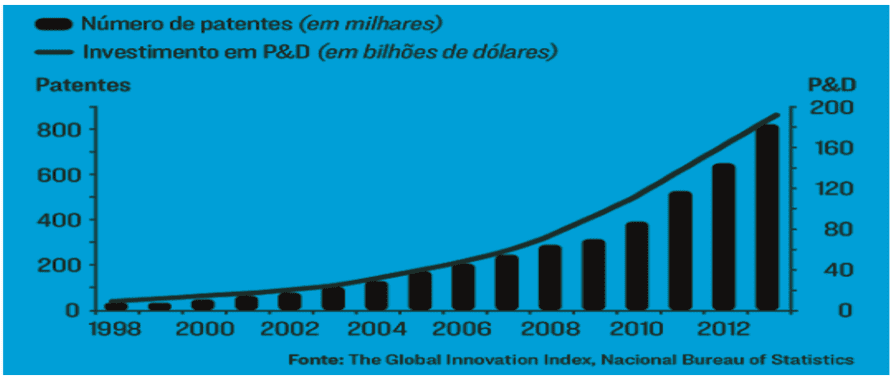

- China is the country that has advanced the most in the global innovation ranking and this is due to the growing investment in research and expansion of the number of patents.

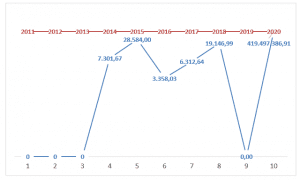

Figure 4 – Patents x P&D (Research and Development).

Like Silicon Valley in the U.S., China has also developed its technology hub in Beijing City, so in the face of the country’s promising scenario, engagement comes from both sides: both from the population and from the Chinese government, which has an important stake in encouraging innovation and entrepreneurship.

The growth of the middle class in China in the last 10 years is unprecedented in the history of mankind. The world’s largest exporter, the country now has the largest consumerist middle class on the planet. Since 2009, China has become Brazil’s largest trading partner, debunking U.S. leadership of about 80 years. The local government acts aggressively and strategically to foster business between China and Brazil. The country is already second with bad “unicorns”, that is, startups valued at more than US$ 1 billion, and is second only to the United States.

In Beijing, the Chinese government invested around US$230 billion in startups in 2015 alone, with the following companies as the following companies: Lenovo, Tencent, Alibaba, Xiaomi, Meituan-Deanping, Didi-Kuadi and Baidu. Since 1978, several special economic zones have been established in China: the first was in Shenzhen City, and also took place in the new districts of Pudong and Zhongguancun. The latter is a neighborhood in northern Beijing and brings together 1 million people and about 20,000 technology companies. That is, one tech company every 50 people!

The Zhongguancun community has become one of the top destinations for not only China’s talents, but also from around the world due to the favorable climate for early stage startups, concentration of talent good performance in production and affordable cost of living.

There is no consensus on whether Chinese Silicon Valley is in the capital Beijing, or in Shenzen, which is 50 minutes from Hong Kong by ferry, so it is worth detailing a little more the development of this region. Shenzhen spends more than 4% of its GDP on research and development, double the continent’s average and in Nanshan the number is more than 6%. Most of this investment comes from private companies. Companies in Shenzhen classify more international patents than in France or Great Britain.

In just two years, Chinese entrepreneurship has become a trend and the country has acknowledged that this initiative accelerates employment, generates wealth and softens financial pressures. At the end of 2016, new public policies were released in order to foster this wave of entrepreneurship. Some examples are:

– Establishment of tax exemptions to companies that create new technologies in order to stimulate development and research;

– Publication of new rules to eliminate barriers in the purchase and sale of technology that by 2015 needed authorization from two different ministries;

– Investments in structure, logistics and employment support in the technology sector;

– Implementation of internet in remote locations.

The Chinese case is emblematic as a proxy for Brazil, because it is notorious for the distancing from the national reality, in recent years, in the face of the enormous advance of innovation of the Asian giant, something that actually alters the dynamics of the financial system, which ceases to serve only the constable entrepreneur, selected by the State, but generalizes the volume of investments based on good projects.

According to a report by China’s Internet Information Center, of the 700 million internet users, 557 million of them use smartphones to stay online and 72.1% of Chinese using the internet are 10 to 39 years old, china Internet Report 2017 reports.

As for the habits of Chinese internet users, there was a 20% increase in the percentage of online purchases compared to 2014. With all this, China’s online retail sales are growing 30% a year and mobile payment volume reached nearly four times last year’s value, reaching $8.6 trillion.

From 2014 to 2016, venture capital funds invested $77 billion in Chinese startups, six times more than in the previous three years. According to the China Startup Outlook 2017 report, Chinese startups believe venture capital funds and private investment are the best sources of capital.

According to CBI Insights, China’s four largest internet companies have invested $5.6 billion in 48 U.S. technology businesses in the past two years. Currently, according to a McKinsey study, the country is among the top three global investment destinations in innovative technologies.

In terms of FinTechs, China is the world leader and by far the largest digital payments market, accounting for nearly half of the global total. In the online lending sector, the country occupies three quarters of the global market. The volume of mobile payments reached nearly four times last year’s figure, reaching $8.6 trillion, compared with just $112 billion in the U.S.

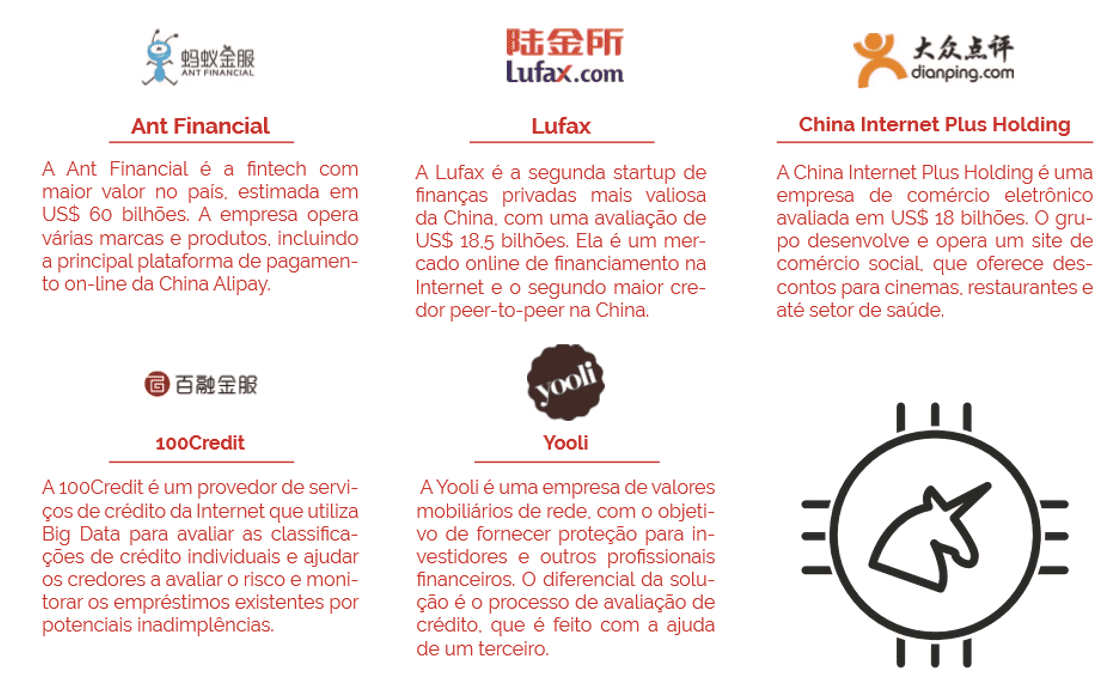

In 2016, investment in finance ventures in China totaled $10.2 billion and exceeded North America’s $9.2 billion. Four of the five most innovative FinTechs in the world are Chinese. The largest of these, Ant Financial, was valued at about US$60 billion, in partnership with UBS, Switzerland’s largest bank.

Figure 2 features some of the main Chinese “unicorns”:

Figure 2 – Top Chinese “unicorns”.

2.4 STRUCTURAL CHANGE PLAN FOR THE NATIONAL FINANCIAL ENVIRONMENT

As FinTechs in Brazil begin to gain market share in each of their respective markets, as well as to open some new markets that are still untapped, Brazilian banks are expected to react. This reaction can come in several ways, the most visible being to imitate the products and services launched by FinTechs. The reaction will be stronger in proportion to the impact, where it is understood that the greatest risk of loss of participation is linked to the emergence of virtual banks. This type of business represents the acceleration spring in the migration of bricks to clicks and, as such, validate the changes brought by FinTechs. The end result, through a quick assessment, is that banks can lose market share (more a slower growth factor than total growth) and margins (as a result of competition), but both can be offset by efficiency gains, reduced risk cost and increased penetration.

One of the strategies used by banks to stem the flow of fintech innovations and outages has been to mimic the products and services launched. However, banks often add their own features to products, which sometimes changes product success to FinTechs.

Here are some examples in the national market:

- Digio, Bradesco and Banco do Brasil. In November 2016, Bradesco and Banco do Brasil launched a new credit card called Digio. It is a fully virtual card, trying to replicate the model successfully used by NuBank. Like NuBank, all interactions would be done via mobile, on a simple platform, and there is no annual fee. However, unlike NuBank, there is no veto of networked candidates, and cards can also be requested at banco do Brasil and Bradesco branches;

- Distribute third-party financing alternatives. Recently, large retail banks have begun distributing financing products from other smaller banks to selected groups of customers (usually high-income customers). This is a response to Orama and Easynvest, which offer several different savings products through their online platform. However, banks charge a higher rate on the distribution of other banks’ financing products, which makes yields less attractive than the same products offered by FinTechs. At the same time, it is a reflection of the large amount of surplus liquidity in the Brazilian financial system, partly due to the limited volume of loan growth in recent years;

- Virtual banking platforms. Itaú Unibanco has more than one million customers registered on its virtual banking platform. Through this platform, the bank interacts with customers mainly via internet, mobile phone and telephone, offering similar services to branches in a virtual way 18 hours a day (as opposed to six hours of branches). Customers are generally at the highest income level, which the bank believes would prefer this new interaction model. Bradesco is considering launching a fully virtual bank, which would be separate from its regular branch-based offering, while still operating within the same IT platform. The services would be similar to those provided by Banco Original or Banco Neon. However, as the services (both for Bradesco’s new online bank and Itaú Unibanco’s virtual bank) would still be offered within a bank of retail branches, they would be subject, in our view, to the limitations of the processes and procedures established for the banking bank. Moreover, the culture of new ventures would still largely be that of the underlying banks, making it more difficult to adopt and develop a truly disruptive technology;

- Financing of FinTechs. Both Itaú Unibanco (Cubo) and Bradesco (InovaBRA) have created state-of-the-art accelerators. These accelerators host conferences for FinTechs and often hire services from companies on a temporary or permanent basis.

The environment has also been shaped from investments by banks directly in FinTechs, mainly through minority holdings. That said, the most visible and successful FinTechs (such as NuBank and GuiaBolso) did not come from these accelerators.

Thus, one of the main trends created to shape the Brazilian banking market in the next ten years is the impetus for virtual banking. Even if banks don’t seem to have the culture to really drive such a disruptive process, they will adopt new technologies over time and this will change the way they interact with customers, deliver and price new products, manage their physical impact, and deploy their capital. The clear areas for better performance come, in our view, from improved operational efficiency, loan subscription best practices and increased penetration of financial services.

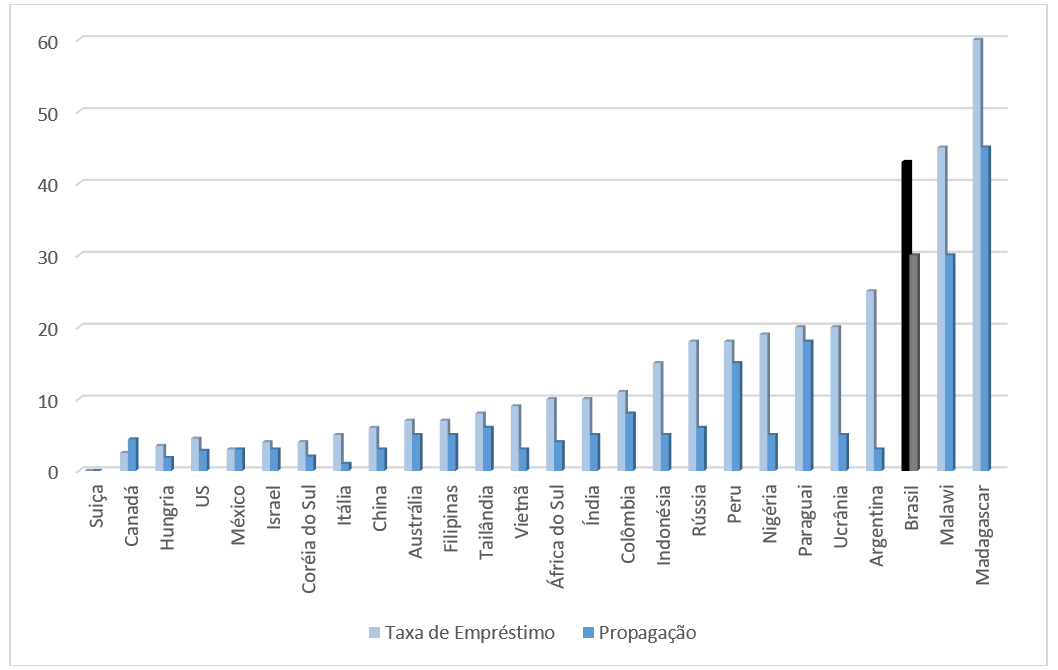

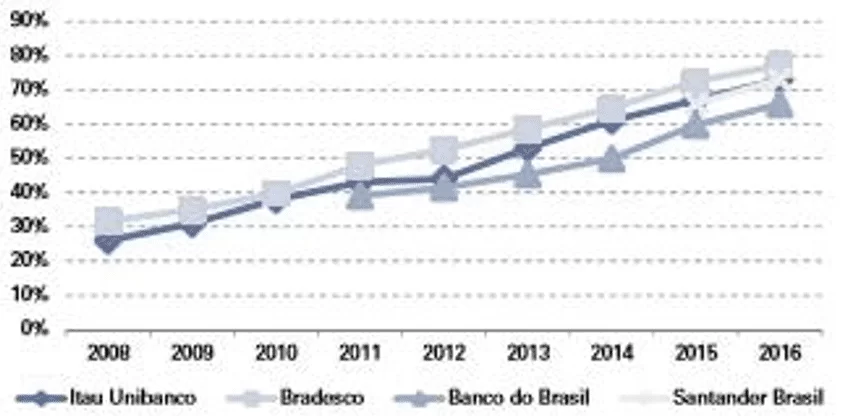

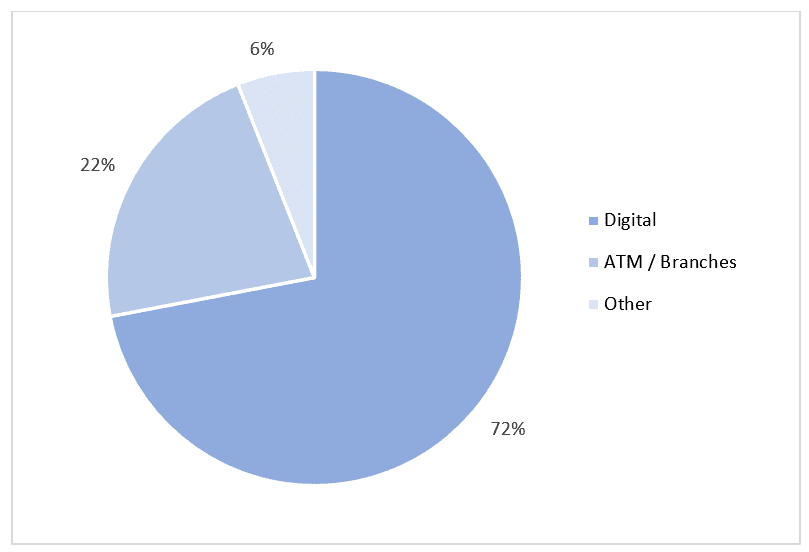

In addition to closing branches, banks are constantly seeking improvements in operational efficiency, but as mentioned above, this process has intensified in recent years. This was largely the case in the form of branch closures and rationalization of employees. But as the Brazilian economy has experienced a long and deep recession in the last three years, it is difficult to separate the adjustments made for cyclical reasons (the recession) from those made for structural reasons (the changing nature of the banking sector). That said, it is necessary to monitor the strength of such adjustments in the next two to three years, leading to more significant investments in IT, more branch closures and reductions in the number of employees. Graphs 6 and 7 illustrate digital and banking transactions:

Figure 6 – Digital transactions (internet and mobile) have become increasingly relevant to banks in recent years. % of transactions made through internet/mobile platforms.

Figure 7 – About three quarters of all bank transactions in major Brazilian banks are digital. Detailing of transactions, Bradesco, Itaú Unibanco, Banco do Brasil.

As information gains better support lending, mm virtual model will probably give banks more points of contact with customers and, as a result, more information with which banks can make their decisions. For example, at a time when Brazil operates essentially a negative credit department (although a more robust model for the positive credit department is in the process of approving Congress), information on borrowers is limited.

Banks are required to rely on statistical analyses of the information provided by borrowers, which increases the chances of type I and type II errors (Inferential errors in hypothesis tests for greater control of sample significance of results).

According to Moules (2014), an online banking experience would generate significantly more data that banks can use to determine credit risk for retail borrowers, which, when combined with the power of big data[13] analytics, could help banks lend to the right borrowers at the right time.

Even if a more robust positive credit department was not under development, technology and big data could in part mimic its function. Academic research shows that positive credit agencies, by replacing negative credit agencies, increase the amount of loans and reduce the cost of risk, which translates into smaller spreads. The combination of these factors would have a positive impact on bank results.

A migration to the digital bank would require a change in the banking culture in Brazil, as well as in the way banks treat their customers. But at the same time, it could serve to attract more customers into the financial system. Because the banking industry is typically seen as a necessary inconvenience, especially among younger customers, circumventing the agency and offering products and services directly to customers through mobile or web-based applications can increase their penetration and sales.

It would be easier to separate services and products and, as a result, charge tailor-made fees, attracting parts of the population, particularly in lower income segments, which are not currently part of the financial system. While a substantial portion of these new customers can be captured by FinTechs, banks should also benefit from higher levels of financial activity and, to some extent, additional customer flow.

3. METHODOLOGY

The methodology of this article, of quantitative nature, seeks to present quantified results through data collection without the use of formal means. The work began in the preparation of a market report with the collection of data originating from Goldman Sachs Bank (2017), on the profound and necessary changes, which the financial environment will suffer in the near future.

Through exploratory research that seeks to ascertain something in an organism, or, in a certain phenomenon to better understand and with greater precision (VERGARA, 2011), we sought to verify the concepts about banking innovation, digital transformation, customer experience, disruptive models, personal finance, regulatory environment and, among other aspects.

The research was developed through a bibliographic survey and literature review of materials already developed on the subject (GIL, 2010). Thus, it was possible to come to understand the dynamics of evolution related to the emergence of financial startups, as well as their ways of acting through FinTechs.

The collection of information in the databases occurred through the use of the Boolean model, in which a document is represented by a composite of indexed terms, and can be defined in two ways: manual or through computational algorithms (UNESP, 2018). Through the Boolean model, information was collected for the preparation of this article, we used terms composed of contents linked by logical operators: AND, OR and NOT, in which contents related to the financial environment were obtained as a result of the research.

4. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Regardless of the country’s strategic positioning in the context of a new financial business model, it is notorious that successful companies will have some common characteristics. The aim of this article is to present the necessary paths for Brazil to evolve in terms of the financial system and its facilities resulting from the new service model for an increasingly connected demand.

The choices that the big banks must make about their future positioning and the path they will engage with other outside parties should determine the resources and energy expenditure for maintaining the customer base and expanding with new market segments. With several reliable ways of playing and strategic postures, there is no one-size-one approach for everyone. Regardless of how the landscape evolves, however, successful banks will have certain common characteristics:

- They will be truly customer-centric, using a deep insight into what customers truly value product development, channel design and experience and price;

- They will be agile and able to adapt to a rapidly changing environment, with mechanisms to track what is happening in the market, assess changes in customer preferences and reorient business to remain relevant;

- They will be excellent in data analysis, not only as a basis for decision making and proposition design, but embedded in products to provide tailored experiences, real-time risk management and dynamic pricing;

- They will be skilled at working with other companies in a complex

ecosystem of partnerships and markets, to provide offers that integrate the best services available in the market to its customers; - They will be excellent at building exciting and safe technology

solutions that enable new functionality to be developed and deployed quickly, and enable easy and secure integration with external systems.

The development of these attributes will not be easy for many organizations, with quite radical changes necessary to their skills, culture and work; as well as the technology platforms that underpin their digital offerings.

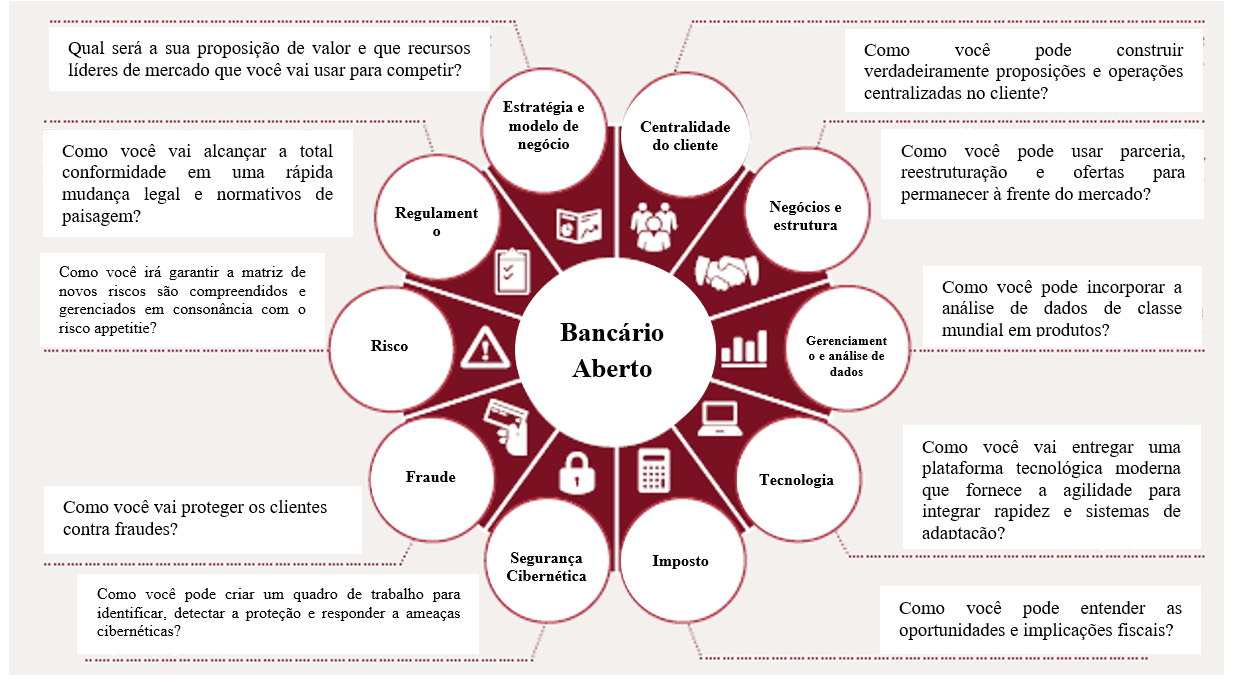

One of the ways that the article unveils to facilitate migration to this new reality is support in the concept of Open Banking together with the resources to be developed, such as incorporating customer focus and increasing value by adding to products. Also, how to organize and leverage external resources and capabilities (either through partnership or acquisition).

Important projects related to technology, including how to build and incorporate analytical data differentiation and artificial intelligence capabilities, such as architecting and developing modular platforms that facilitate the integration and deployment of new innovative features will be basic requirements for success in an extremely competitive environment. So the big national banks need to be clear about how they will manage cyberspace in terms of information security, customer base maintenance, operating systems and secure data, and how they will protect customers from fraud.

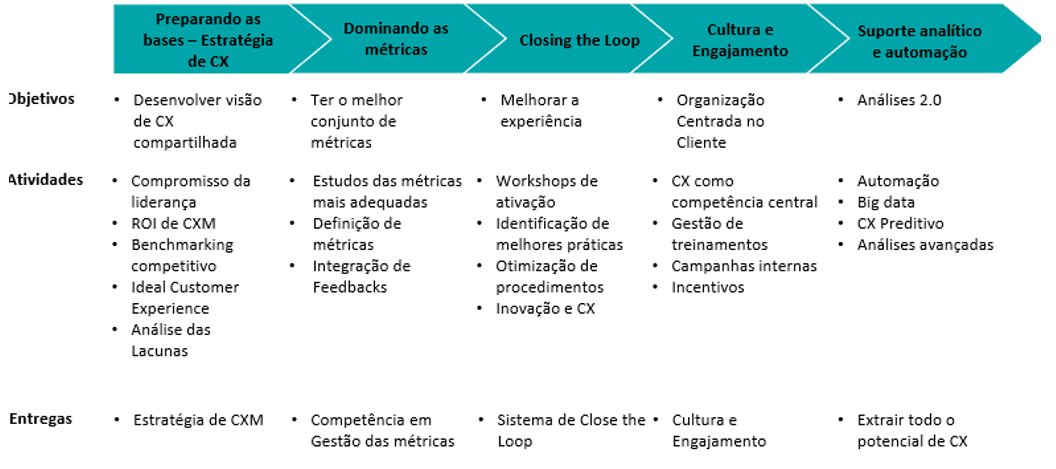

While the future is unpredictable, there are many practical measures that banks can take immediately. Below is Figure 3, a scheme proposed by Reincheld (2018) and Rawson et. Al. (2013) on how to implement an innovation proposal.

Figure 3 – Step by step of a management and innovation program in CX.

With regard to operational possibilities, it follows a model proposed by the consulting team of Price Waterhous Coopers, adapted by the authors, in the search to transform the internal environment of a large bank by expanding its boundaries of operation according to Figure 4:

Figure 4 – Open Banking Model.

REFERENCES

ALECRIM, Emerson. O que é Fintech? Info Wester, 31 mar. 2016. Disponível em: https://www.infowester.com/fintech.php. Acesso em: 05 abr. 2019.

AMORIM, Lucas. País das cópias virou polo de inovação – e isso muda o mundo. Revista Exame, 30 nov. 2017. Disponível em: https://exame.abril.com.br/revista-exame/e-hora-de-copiar-a-china/. Acesso em: 25 mar. 2019.

BANCO CENTRAL DO BRASIL (BACEN). Relatório de economia bancária: 2018. Brasília, DF: Banco Central do Brasil, 2018.

BANCO GOLDMAN SACHS. Future of finance: Fintech’s Brazil moment. New York: Goldman Sachs Global Investment Research, 2017.

BERMUDEZ, Jocelyn. China may soon surpass U.S. in the Global Education Technology Market. Ed Tech Times, 7 oct., 2016. Disponível em: https://edtechtimes.com/2016/10/07/china-may-soon-surpass-u-s-in-the-global-education-technology-race/. Acesso em: 10 mar. 2019.

BUCHAK, G., MATVOS, G. PISKORSKI, T. SERU, A. FinTech, regulatory arbitrage, and the rise of shadow banks. NBER Working Papers, n. 23288, mar. 2017.

CAMBRIDGE Centre for Alternative Finance. Sustaining momentum: the Second European Alternative Finance Industry Report, sep. 2016.

CAMBRIDGE Centre for Alternative Finance and Chicago-Booth Polsk. Center Breaking new ground: the Americas Alternative Finance Industry Report, April. (2016):

CAMBRIDGE Centre for Alternative Finance and Nesta. Pushing boundaries: the 2015 UK Alternative Finance Industry Report, mar. 2016.

CAMBRIDGE Centre for Alternative Finance and Nesta. Pushing boundaries: the 2015 UK Alternative Finance Industry Report, mar. 2016.

CAMBRIDGE Centre for Alternative Finance and University of Sydney Business School. Harnessing potential: the Asia-Pacific and China alternative finance benchmarking report, mar., 2016.

CARNEY, M. The promise of FinTech: something new under the sun? Speech at the Deutsche Bundesbank G20. Conference on Digitising finance, financial inclusion and financial literacy, Wiesbaden, 25 jan., 2017.

COMMITTEE on Payments and Market Infrastructures. Distributed ledger in payment, clearing and settlement: an analytical framework. Feb., 2017.

DAVIS, K.; MURPHY, J. Peer-to-peer lending structures, risks and regulation. The Finsia Journal of Applied Finance, v. 3, 2016, p. 37–44.

DE ROURE, C.; PELIZZON, L.; TASCA, P. How does P2P lending fit into the consumer credit market? Deutsche Bundesbank Discussion Papers, n. 30, 2016.

DEER, L.; MI, J.; YUXIN, Y. The rise of peer-to-peer lending in China: an overview and survey case study. Association of Chartered Certified Accountants, 2015.

DEMYANYK, Y.; KOLLINER, D. Peer-to-peer lending is poised to grow. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, aug. 2014.

DIXON, Matthew; FREEMAN, Karen; TOMAN, Nicholas. Customer effort ratio: stop trying to delight your customers. Harvard Business Review, v. 88, n. 7/8, jul.-aug., 2010, p. 116-122. Disponível em: https://hbr.org/2010/07/stop-trying-to-delight-your-customers. Acesso em: 18 mar. 2019.

GIANCOTTI, James. Beijing: one of the top startup ecosystems in Asia. Forbes, 09 aug. 2016. Disponível em: https://www.forbes.com/sites/jamesgiancotti/2016/08/09/beijing-one-of-the-top-startup-ecosystems-in-asia/#6203cdc125cb. Acesso em: 10 abr. 2019.

GIL, Antônio Carlos. Como elaborar projetos de pesquisa. 5. ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 2010.

IN FINTECH, China shows the way. The Economist, 25 feb. 2017. Disponível em: https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2017/02/25/in-fintech-china-shows-the-way. Acesso em: 22 mar. 2019.

INCENTIVO ao empreendedorismo: um negócio da China. Isto é dinheiro, n. 1116, 22 mai. 2017. Disponível em: https://www.istoedinheiro.com.br/incentivo-ao-empreendedorismo-um-negocio-da-china/. Acesso em: 16 abr. 2019.

INTERNATIONAL Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS). FinTech developments in the insurance industry, 21 fev. 2017.

INTERNATIONAL Organization of Securities Commissions. Research Report on Financial Technologies (FinTech), feb. 2017.

JENIK, I.; LYMAN, T.; NAVA, A. Crowdfunding and financial inclusion. [S. l.]: Working Paper, 2017.

JOURDAN, Adam. Digital doctors: China sees tech cure for healthcare woes. Reuters, 14 oct., 2014. Disponível em: https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-china-healthcare-digital/digital-doctors-china-sees-tech-cure-for-healthcare-woes-idUKKCN0I32OX20141014. Acesso em: 11 abr. 2019.

KEININGHAM, T. L.; COOIL, B.; AKSOY, L.; ANDREASSEN, T. W.; WEINER, J. (2007). The value of different customer satisfaction and loyalty metrics in predicting customer retention, recommendation, and share-of-wallet. Managing service quality: an international Journal, v. 17, n. 4, p. 361-384. Disponível em: http://www2.owen.vanderbilt.edu/bruce.cooil/documents/publications/msq2007.pdf. Acesso em: 07 abr. 2019.

KIRBY, E.; WORNER, E. Crowdfunding: an infant industry growing fast. International Organization of Securities Commissions, mar., 2014.

MAGIDS, Scott; ZORFAS, Alan; LEEMON, Daniel. The new science of customer emotions. Harvard Business Review, v. 76, nov., 2015, p. 66-74. Disponível em: https://hbr.org/2015/11/the-new-science-of-customer-emotions. Acesso em: 10 mar. 2019.

MARKEY, Rob; REICHHELD, Fred; DULLWEBER, Andreas. Closing the customer feedback loop. Harvard Business Review, v. 87, n. 12, dec., 2009, p. 43-47. Disponível em: https://hbr.org/2009/12/closing-the-customer-feedback-loop. Acesso em: 04 mar. 2019.

MILNE, A.; PARBOTEEAH, P. The business models and economics of peer-to-peer lending. European Credit Research Institute, 2016.

MORESI, Eduardo (org.). Pró-reitoria de Pós-graduação (org.). Metodologia da pesquisa. Brasília: Universidade Católica de Brasília, 2003. Disponível em: http://www.inf.ufes.br/~falbo/files/MetodologiaPesquisa-Moresi2003.pdf. Acesso em: 27 jun. 2014.

MORSE, A. Peer-to-peer crowdfunding: information and the potential for disruption in consumer lending. NBER Working Papers, n. 20899, jan.-may., 2015.

MOULES, J. Santander in peer-to-peer pact as alternative finance makes gains. Financial Times, 17 jun., 2014.

ORTUS round table: the future of China’s innovation hubs. Ortus Club, 13 dec. 2017. Disponível em: http://ortus.club/uncategorized/nova-china-innovation/. Acesso em: 11 abr. 2019.

POWELL, Brian. Agritech startups in 2016: saw less investment but more diversification. Yostartups.com, 8 mar. 2017. Disponível em: https://yostartups.com/agritech-2016-witnessed-less-investment-diversification/. Acesso em: 03 mar. 2019.

PRICE Water House Coopers. Peer pressure: how peer-to-peer lending platforms are transforming the consumer lending industry, fev., 2015.

RATINECAS, Paulo. Ecossistema empreendedor da China. 6 mar. 2019. Disponível em: https://www.slideshare.net/ratinecas/ecossistema-empreendedor-da-china-estudo-startse. Acesso em: 28 mar. 2019.

RAU, R. Law, trust, and the development of crowdfunding. University of Cambridge Woking Paper, 2017.

RAWSON, Alex; DUNCAN, Ewan; JONES, Conor. The truth about customer experience. Harvard Business Review, v. 91, n. 9, set., 2013, p. 90-98. Disponível em: https://hbr.org/2013/09/the-truth-about-customer-experience. Acesso em: 04 mar. 2019.

REICHHELD, F. F. The one number you need to grow. Harvard business review, v. 81, n. 12, dec., 2003, p. 46-55.

REICHHELD, F. F.; SASSER JR., W. E. Zero defections: quality comes to services. Harvard Business Review, v. 68, n. 5, sep.–oct., 1990, p. 105–111.

SAKAMOTO, Camila. Shenzhen: a cidade da inovação. China Link Trading, 02 mai. 2017. Disponível em: http://www.chinalinktrading.com/blog/shenzhen-cidade-da-inovacao/. Acesso em: 03 abr. 2019.

TOP 6 fast growing Tech Industries in China: artificial intelligence & healthtech (part 2/3). Thexnode.com, 20 dec., 2016. Disponível em: http://www.thexnode.com/blog/top-6-fast-growing-tech-industries-in-china-artificial-intelligence. Acesso em: 13 mar. 2019.

TOP 6 fast growning Tech Industries in China: Fintech & Edtech (part 1/3). Thexnode.com, 30 nov. 2016. Disponível em: http://www.thexnode.com/blog/top-6-fast-growing-tech-industries-in-china-fintech-edtech-part-1-3. Acesso em: 13 mar. 2019.

UNESP. Modelos de recuperação da informação. 23 ago. 2018. Disponível em: https://www.marilia.unesp.br/Home/Instituicao/Docentes/EdbertoFerneda/ri04—modelosri.pdf. Acesso em: 05 abr. 2019.

USUÁRIOS de internet na China ultrapassam os 649 milhões em 2014. O Globo Economia, 03 fev. 2015. Disponível em: https://oglobo.globo.com/economia/tecnologia/usuarios-de-internet-na-china-ultrapassam-os-649-milhoes-em-2014-15231412. Acesso em: 03 abr. 2019.

VALENTE, Jonas. Relatório aponta Brasil como quarto país em número de usuários de internet. Agência Brasil, 03 out. 2017. Disponível em: http://agenciabrasil.ebc.com.br/geral/noticia/2017-10/relatorio-aponta-brasil-como-quarto-pais-em-numero-de-usuarios-de-internet. Acesso em: 02 abr. 2019.

VERGARA, Sylvia Constant. Projetos e relatórios de pesquisa em administração. 13. ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 2011.

WANG, Yue. Will the future of artificial intelligence look Chinese? Forbes, 6 nov. 2017. Disponível em: https://www.forbes.com/sites/ywang/2017/11/06/will-the-future-of-artificial-intelligence-look-chinese/#48cac8f77fdc. Acesso em: 05 abr. 2019.

XIANG, Nina. China is quietly catching up on healthcare technology. China Money Network, 31 mar. 2017. Disponível em: https://www.chinamoneynetwork.com/2017/03/31/china-is-quietly-catching-up-on-healthcare-technology. Acesso em: 15 mar. 2019.

XIANG, Nina. Here are China’s top 10 aI companies challenging US tech leadership. China Money Network, 07 mar. 2017. Disponível em: https://www.chinamoneynetwork.com/2017/03/07/here-are-chinas-top-10-ai-companies-challenging-us-tech-leadership. Acesso em: 15 mar. 2019.

YEUNG, Edith. China internet trends 2017. Disponível em: https://pt.slideshare.net/EdithYeung/china-internet-report-2017-by-edith-yeung. Acesso em: 25 mar. 2019.

APPENDIX – FOOTNOTE REFERENCES

3. FinTechs – financial services companies with processes entirely based on technology, among which stand out: payments, loans, insurance and investments.

4. Startups – business model developed by recent companies, related, in general, to innovation and technology.

5. Spreads – difference between buy and sell price, i.e. the surcharge charged on a financial transaction.

6. Equity research – segment within the financial market responsible for studying and analyzing in detail the information of a company and its business as a whole, aiming at investment opportunities.

7. Crowdfunders – investment modality where several people can invest small amounts of money in a given business, usually via the internet, in order to give life to an idea.

8. P2P – Peer-to-peer English, which means peer-to-peer, is a network format of computers with decentralized functions of conventional network functions, where the computer of each logged-on user ends up performing server and client functions at the same time.

9. Herfindahl Hirschman – is a common measure of market concentration, used to determine the competitiveness of it. It is calculated by fitting the participation and market of each company in a competitive environment. It can range from zero to 10,000. The U.S. Department of Justice uses it to assess potential merger problems, and regulators identify from it whether any sector can be considered competitive or operating under a particular monopoly.

10. Insper – is a Brazilian higher education institution that operates in the areas of business, economics, law, mechanical engineering, mechatronics engineering and computer engineering.

11. IAIS – International Association of Insurance Supervisors.

12. CAGR – Compound Annual Growth Rate.

13. Big Data – is the analysis and interpretation of large volumes of data of great variety. This will allow IT professionals to work with unstructured information at a high speed.

[1] Professional Master’s degree in Management Systems.

[2] PhD in Production Engineering. Master’s degree in Civil Engineering. Graduation in Civil Engineering.

Submitted: September, 2020.

Approved: October, 2020.