REVIEW ARTICLE

OLIVEIRA, Carliane Ribeiro de [1]

OLIVEIRA, Carliane Ribeiro de. Coping with the Phenomenon of Domestic Violence and the Forms of Assistance to Women. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 05, Ed. 12, Vol. 13, pp. 134-172. December 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/social-sciences/phenomenon-of-violence

ABSTRACT

Domestic violence stands out in the Brazilian reality for the aggressions suffered by women in a private context (mainly by partners and close family members) and in the public sphere through the sexist culture in the social order. In this sense, the present study aims to analyze the confrontation with the phenomenon of domestic violence in the context of violence against women and the ways of attending to it. It is, therefore, a qualitative research, of an exploratory nature, to be carried out by the techniques of bibliographic research from the existing norms in the social and political sphere. The study made it possible to visualize that, despite the advances in relation to women’s rights in Brazil, thanks to the various feminist movements and the creation of laws that safeguard women in the preservation of their rights, policies that are carried out more forcefully are still necessary and with the effective commitment of the state and society as a whole.

Keywords: Assistance To Women, Confrontation, Domestic Violence.

1. INTRODUCTION

Violence against women is a topic that has occupied a prominent place among the daily concerns of governments and society in general, generating government policies and social movements in several countries around the world. In Brazil, it is known that violence against women stands out, mainly, for the aggression inserted in a private and public context in cultural, political and social aspects. This world reality is configured by the image of patriarchy that disposes of the domination of women by men.

With the increase in the number of cases of violence, it is necessary to receive them in Reference Centers that establish measures to protect women at risk through the insertion of policies capable of breaking this cycle. Motivated by the perception of how the problem of violence against women is strongly rooted in Brazilian society, the present work discusses the theme of confronting the phenomenon of domestic violence and the forms of assistance to women.

In this way, the general objective of the research is to analyze the confrontation with the phenomenon of domestic violence in the context of violence against women and the ways of attending to it. As specific objectives, we intend to conceptualize domestic violence, demonstrate the forms of violence practiced by the aggressors and verify the acceptance of protective measures and acts linked to the other legal provisions of the Maria da Penha Law.

To achieve the proposed objectives, the methodology used in this investigation is characterized as a qualitative research, of an exploratory nature, to be carried out by the techniques of bibliographic research from the existing regulations in the social and political sphere, in addition to a bibliographic review based on authors such as Dias (2012), Minayo (2015), Dilva (2019), Saffioti (2004).

2. DEVELOPMENT

2.1 CONCEPTS OF VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN

Violence is understood as excess of force, a behavior or action that causes harm to another person, a living being or an object manifested in all periods of humanity. It does not respect the autonomy, physical or psychological integrity or even the life of another. The term derives from the Latin violentia (which in turn is broad, derives from vis, force, vigor); it is the application of force against anything or being (MINAYO, 2015).

This violence is not always characterized by physical aggression, given that it can be the domination of one class over another or of one person against another. That is, violence can prevent someone from expressing themselves and making their own decisions because they consider that person to be intellectually or socially inferior. In Brazilian culture, violence is not restricted to physical aggression, as it is also part of language. Violent reality has many facets of real and symbolic, physical and verbal violence, in a wide field of attitudes and realities that are summarized by the excess and abuse of power (REIS, 2008).

According to Dias (2008) there is widespread and rampant violence in society. The author understands that a child, for example, who witnesses violence throughout his childhood, can only consider the use of trivial physical force to solve his problems. In addition, the child generates a great perpetuating effect, since its agents reproduce the behavior experienced within the family. That is why the family is responsible for the great changes that society has been going through by perpetuating, even if unconsciously, violence.

For Teles and Melo (2003, p. 15):

[…] Violência se caracteriza pelo uso da força, psicológica ou intelectual para obrigar outra pessoa a fazer algo que não está com vontade; é constranger, é tolher a liberdade, é incomodar, é impedir a outra pessoa de manifestar seu desejo a sua vontade, sob pena de viver gravemente ameaçada ou até mesmo ser espancada lesionada ou morta. É um meio de coagir, de submeter outrem ao seu domínio, é uma violação dos direitos essenciais do ser humano. (TELES e MELO, 2003)

Soares (2004) states that a woman victim of violence lives with shame and fear, as she is not respected and heard by her aggressor and, thus, a feeling of powerlessness arises. In this sense, the way her reactions are manifested comes from her relationship with her partner.

According to information from the Special Secretariat for Policies for Women (2003), moments of violence are not continuous, that is, there are bad phases, but there are also harmonious phases. It is in these moments that they end up giving their partner a chance, believing that he only raped her because of other problems that influenced him, such as alcohol, drugs, work problems or even financial difficulties.

For Dias (2008), violence against women is rooted throughout history in the face of culture, tradition, ideology, etc. The figure of the woman is still, for many, seen as inferior to that of the man. Therefore, when they try to seek equality within the social environment, they suffer violence of all kinds. The author also states that the most common cause of domestic violence is when the woman is raped every day and then ends up forgiving her partner when he swears and promises that he will get better. This works as if it were an apology that of course, may or may not be accepted by the victim; if there is denial of violence, it can happen again immediately. (DIAS, 2008)

Given this, Dias (2008) states that this cycle is perverse, because at first man is silent, becoming indifferent. Soon after, the complaints, repressions and disapprovals of the woman’s actions begin, with punishments and punishments taking place. What was once just verbal aggression becomes physical aggression that intensifies over time.

In addition, the man destroys the victim’s belongings and personal objects as a way of humiliating and manipulating her. However, outside the home environment, the aggressor appears to be a great person. It is observed, therefore, that the discrimination of women is naturalized, as it is assimilated by the culture, by the woman herself and by the male eyes. In this aspect, socialization needs to be able to analyze and put into perspective the production and reproduction of this ideology that makes women inferior, in addition to understanding how the construction and sharing of this knowledge takes place. Whether in the family or at school, it is essential to reformulate this sexist and sexist mentality (SANTOS, 2010).

In a patriarchal society where masculinity is linked to a culture of honor and pride, men want to maintain control and power over women. It is exactly when these factors that structure the relational dynamics between men and women break down, violence is resorted to (MACHADO, 2014).

A survey by Agência Patrícia Galvão (2017) revealed an increase in the number of women who have suffered some type of domestic violence: the percentage increased from 18% in 2015 to 29% in 2017. There was an increase in the percentage of women who have already suffered domestic or family violence committed by a man: 56% in 2015 to 71% in 2017. It is noticed that the rates of domestic violence against women are alarming, but even so there is still great difficulty on the part of the victim to lose the fear of denouncing their aggressor. Women themselves need to be more empowered. (INSTITUTO PATRÍCIA GALVÃO, 2010-2017)

This empowerment consists of becoming aware of oneself, of one’s possibilities, in a process of affirmation that emerges from interaction with other women, opposing the limitations imposed by a patriarchal society (AGUIAR, 2015). For Saffioti (2008) empowerment is related to the change in power relations in favor of women who have little control over their living conditions, which implies the right to have control over their financial, physical, intellectual, and social resources etc. In this way, violence against women involves a denial of citizenship rights for women, which places them in a situation of lack of empowerment and social power.

Therefore, it is necessary to have more social than legal knowledge about the social factor. Initially, it is necessary to conclude what are the most frequent causes that lead men to commit violence against women and to live without any kind of guilt and punishment (DIAS, 2010).

It is also necessary to understand what motivates and leads human beings to commit crimes that are so degrading to family life. For this reason, the search continues to combat this crime that occurs in the family cycle and to understand the reason for such excessive violence against women (LORENZ, 1979).

2.2 DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN AS A SOCIAL PROBLEM

Domestic violence against women is a serious problem that must be addressed as a priority by both society and government agencies. Both must work together to create public policies that prevent and combat violence, as well as strengthen the victim support network.

In this sense, it is extremely important that cases of violence are not understood only at the individual and private levels, but rather as a matter of human rights, given that violence prevents the full development of women’s citizenship. It is necessary to create means to dismantle the pillars of violence against women and an important step is to question the way society is structured and organized, that is, to reflect on the unequal power relations between men and women.

In the Federal Constitution of 1988, the right to non-violence and gender equality is explicit, defining state responsibility in combating this practice (BRASIL, 1988). The mobilization of feminist and gender movements in Brazil achieved, in addition to this consent in the Magna Carta, the creation, still in 2004, of Law nº 10.886/04, which added two paragraphs to Art. 129 of the Penal Code (Decree-Law no. 2,848/40), creating the special type of crime called “Domestic Violence”.

Continuing with this recognition, in August 2006, the Federal Government sanctioned Law 11,340/06, also known as the Maria da Penha Law, representing a significant advance in the fight against impunity for violence against women. Its name comes from the tribute to Maria da Penha Maia Fernandes, from Ceará, who was a victim of domestic and family violence and who fought for years to have her aggressor legally punished. According to the Maria da Penha Law, in its Art. 2nd.

Toda mulher, independente de classe, raça, etnia, orientação sexual, renda, cultura, nível educacional, idade e religião, goza dos direitos fundamentais inerentes à pessoa humana, sendo-lhe asseguradas as oportunidades e facilidades para viver sem violência, preservar a sua saúde física e mental e seu aperfeiçoamento moral, intelectual e social. (Op. Cit., 2006)

2.3 TYPOLOGIES OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN

Table 1- Types of violence against women

| TYPES | DEFINITION |

| Physical Violence | Understood as any conduct that offends your bodily integrity or health. |

| Psychological Violence | Understood as any conduct that causes emotional damage and lower self-esteem or that harms and disturbs full development. This type of violence aims to degrade or control their actions, behaviors, beliefs and decisions, through threats, embarrassment, humiliation, manipulation, isolation, constant surveillance, persistent persecution, insults, blackmail, ridicule, exploitation and limitation of the right to go and come or any other means that harms psychological health and self-determination. |

| Sexual Violence | Understood as any conduct that compels you to witness, maintain or participate in unwanted sexual intercourse, through intimidation, threat of coercion or use of force; that induces her to commercialize or use, in any way, her sexuality, that prevents her from using any contraceptive method or that forces her into marriage, pregnancy, abortion or prostitution, through coercion, blackmail, bribery or manipulation; or that limits or nullifies the exercise of their sexual and reproductive rights. |

| Property Violence | Understood as any conduct that configures retention, subtraction, partial or total destruction of their objects, work instruments, personal documents, assets, values and economic rights or resources, including those intended to satisfy their needs. |

| Moral Violence | Understood as any conduct that constitutes slander, defamation or injury. In this context, it should also be noted that this type of violence is closely linked to psychological violence. |

Source: (BRASIL, 2011). Table organized by the author

It is verified, therefore, from the Maria da Penha Law, that violence is not always characterized by physical aggression, as it can also be manifested by the domination of one class over another, of one person against another. Thus, the act of preventing someone from expressing themselves and making their own decisions because they consider them intellectually or socially inferior is also an act of violence.

2.3.1 PATRIARCHY

Historically, women have an inferior image in relation to men, as they have always enjoyed the privileges of their own patriarchal society, with women only taking care of the family and home. It is evident, therefore, that she has always been treated as inferior to men throughout history, so that submission has accompanied her over the years.

From a very early age, men are programmed to respond to social expectations that expect them to be aggressive, competitive and to assume passionate or self-destructive postures. The notion that the boy has to be “macho”, virile and competitive develops in different ways and in different places, such as in children’s games, in media segmented by age and sex, in the streets, in schools, in homes, in bars, in barracks, in prisons, in war, etc. That is, they are socialized to repress their emotions, with anger and even physical violence being socially accepted as masculine expressions of feelings and demonstration of power (CRESS, 2003).

Thus, violence against women can be explained as a phenomenon that is constituted from the naturalization of the difference between the sexes. This is based on hierarchical categories, historically created, as it is a theme that refers to social relations in which there is a dominating and a submissive being, thus constituting a type of social relationship of power. As it is produced in social relations, it is perceived, above all, as gender inequalities (GUEDES et al., 2009).

The cultural plot of violence against women takes place historically, given that it is a narrative based on the patriarchal order that imposes a generalized division of the world and, therefore, inequalities between men and women. In this way, the macho culture imposes the places, the positions that are defined according to their gender. It establishes an inequality by placing men in a position of superiority in relation to women (NAVARRO, 2001).

Violence is often used in a subtle way, that is, the aggressor takes some care to dominate the emotional state of the other, leaving him always on alert, afraid of what might happen if he has any reaction against him.

The concept of gender has been built and fed on the basis of symbols, norms and institutions that define the models of masculinity and femininity and the standards of behavior accepted or not for men and women. Gender is a social construction superimposed on a sexed body, that is, it is a form of meaning of power.

In this sense, Saffioti (2004) points out that one of the reasons for the occurrence of violence against women is the rupture in the hierarchical relationship established between the genders, because as power is essentially masculine and virility is measured by the use of force , the basic conditions for the exercise of violence, that is, physical violence, are gathered in the hands of men.

Another factor that contributes to the cause of violence is the fact that women do not report the aggression, because they are afraid of being threatened and because they are highly dependent on their partners. It is important to emphasize that violence is an issue that is embedded in cultural practices in all societies, regardless of their income or formal education.

The determination of violence concerns historical, contextual, cultural, structural and interpersonal factors. The phenomenon of domestic violence is intrinsically related to the social environment and is independent of color, religion and social class. Despite being equal before the law, these are not always recognized, since they do not change the customs of the past that are characterized by violence against women. Unfortunately, domestic violence is a historical issue that is part of the reality of thousands of women (SAFFIOTI, 2004).

Thus, in both cases, they are faced with a power relationship characterized by domination and objectification. Violence is a question of power legitimized by the culture in which the strongest feel they have the right to subjugate the weak, that is, power is not in human nature, but in a behavior incorporated by several generations.

2.3.2 IBGE DATA ON VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN

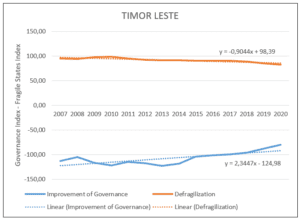

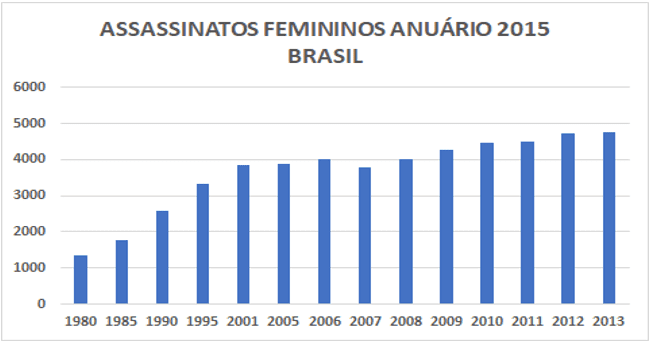

Violence against women grows so strongly in Brazilian society that the annual rate is 4.8 female murders per 100,000 women, which occur from 1980 to 2013, placing Brazil in 5th position among the countries with the highest homicide rate female. According to data from Waiselfisz (2015), Brazil has already been condemned by the UN committee for violating women’s human rights in view of the high rate of violence in the country.

Image 1- Number and rates (per 100 thousand) of female murderers in Brazil 1980/2013

Image 2- Female homicide rates in 2006/2013 with 2.6 per year rate growth drops to 1.7 per year

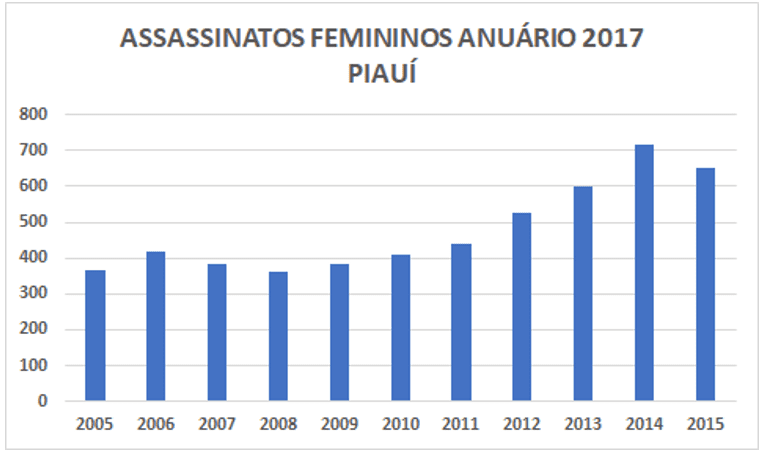

The rate of deaths of women from homicides in Brazil increased in 18 of the 27 federal units between 2005 and 2015.

Image 3- In Piauí, growth of 76.6%, according to data released by ATLAS DA VIOLÊNCIA 2017

3. WOMEN’S PROTECTION LEGISLATION: HISTORY OF STRUGGLES FOR RIGHTS

Violence against women is a worldwide cultural issue that takes place in various forms and is classified as repression, submission and discrimination committed by men. Such discrimination led women to claim their rights as a category. The struggle for recognition in society begins in the 19th century in Brazil with the feminist movement that gained strength to fight and claim together with the State in the 1970s. This movement aimed to implement public policies aimed at combating violence against women .

At the beginning of the 19th century, the first records of women’s struggle for their rights can be found in Brazil, even if more restricted to the middle and upper classes of society. In Brazil, the Feminist Movement emerged in 1850 when a small group of women became dissatisfied with the traditional roles assigned by men to women. However, feminism became visible in Brazil only at the beginning of the 20th century, more precisely in 1910 when women began the struggle for the right to vote for women (SCHRAIBER, 2005).

That year, professor Deolinda Daltro founded the Partido Republicano Feminino with the aim of debating the female vote. In 1917, she led a march demanding the extension of the vote to women, and in 1932, the then president Getúlio Vargas, by enacting the Electoral Code, granted the right to vote to women (REIS, 2008).

Bastos (2016) denotes that the year 1932, during the government of Getúlio Vargas, was a great mark of the conquest of women in the country due to the right to vote. Despite not enjoying the fullness of this achievement until the 1940s. During this period, Brazilian women began to unify themselves in favor of more participation in the political and economic life of the country, reaching the 1950s, representing 14% of the active population of the country (REIS, 2008).

During the so-called “economic miracle” there was a break in traditional ties arising from the accelerated modernization promoted by the military dictatorship, mainly between individuals and groups and the nuclear family structure. The increase of women in the labor market changed the normative patterns of the ideology of domesticity (REIS, 2008).

Another important point is that women gained greater sexual freedom with the emergence of contraceptive pills. In this way, the feminist movement gained more strength, as explained by Melo (2013) when he states that, prior to that time, relationships were entirely monogamous and focused on marriage, and single mothers were seen with great prejudice. In this sense, the affirmation of equality between the sexes will converge with the economic needs of this historical moment.

In the scope of Law as well as History, women remained excluded for a long time, mainly due to the sexual division of labor and due to their biological characteristic of reproducing the species and the fragility in the face of the physical strength of the opposite sex – the man.

Some factors such as the complex connection of factors such as the massive entry of women into the labor market, the need to reconfigure the family, access to education, technological advances in the reproductive field and the relationship between poverty and femininity have been identified as reasons for the transformation of the legal status of women. The United Nations recognizes that:

“Promoting equality between men and women helps in stable growth and development of economic systems, with social benefits measurable through economic indicators”. (ONU, online)

Such data indicate that discrimination against women causes a serious threat to human rights, as it has a strong negative impact on economic and social development. Teles and Melo (2003, p. 13) conclude that:

[…] buscar e consolidar melhores condições de vida para as mulheres do mundo, além de uma questão de direitos humanos, deve ser encarado como uma prioridade para o desenvolvimento de uma sociedade mais justa. (TELES e MELO, 2003)

The history of human rights emerged with the promulgation of declarations of rights at the end of the 18th century, such as the American Declaration of Virginia of 1776, and the French Declaration of 1789, which gave an innovative and revolutionary meaning to the human condition of the person (TELES and MELO , 2003).

On March 31, 1953, in New York, the Convention on the Political Rights of Women was signed on the occasion of the VII Session of the United Nations General Assembly. In Brazil, it was signed in May 1953, being approved by Legislative Decree 123/55. But ratification took place only on August 13, 1963. Enactment came with President João Goulart’s Decree 52476/63. This Convention promulgates:

Reconhecendo que toda pessoa tem o direito de tomar parte na direção dos assuntos públicos de seu país, seja diretamente, seja por intermédio de representantes livremente escolhidos, ter acesso em condições de igualdade às funções públicas de seu país e desejando conceder a homens e mulheres igualdade no gozo e exercício dos direitos políticos, de conformidade com a Carta das Nações Unidas e com as disposições da Declaração Universal dos Direitos do Homem. (BRASIL, 1963)

In 1966, the International Covenant was adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations, which formulated in detail the content of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948. politicians between men and women.

This text was only approved in Brazil in 1991 through Legislative Decree 226, which was enacted by Decree 592/92. With this attitude, the Brazilian State assumed legal obligations at the international level regarding the guarantee of human rights, specifically on civil and political rights, committing to present reports on the measures taken to guarantee the rights enshrined in the international instrument (REIS, 2008).

Other innovations emerged in 1969 with the Pact of San José of Costa Rica which, in addition to reaffirming the aforementioned pact, defends in its article 5 respect for physical, psychological and moral integrity. The idea of the pact already reveals concerns of violence with every person, establishing that “no one should be subjected to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Every person deprived of liberty must be treated with respect due to the inherent dignity of the human being”. Brazil only adhered to this pact in 1992, that is, it can be seen how late it was before the international scene in these issues of protection of human rights.

In 1975, the First World Convention on Women took place in Mexico, which elaborated the First Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, according to the understanding of the States:

[…] significa toda distinção, exclusão ou restrição a fundada no sexo e que tenha por objetivo ou consequência prejudicar ou destruir o reconhecimento, gozo ou exercício pelas mulheres, independentemente do seu estado civil, com base na igualdade dos homens e das mulheres, dos direitos humanos e liberdades fundamentais nos campos político, econômico, social, cultural e civil ou em qualquer outro campo. (BRASIL, 2004)

This Conversion reiterated health protection, in addition to ensuring the right to social security and maternity leave, with access to medical services, including family planning. There was also reference to rural workers, addressing specific problems faced by this population. Furthermore, it covered their legal capacity, which must be identical to that exercised by men.

In the 1980s, Brazil was the scene of numerous manifestations of feminist movements aimed at combating violence against women. During this period, “domestic violence” was officially recognized for the first time as a specific type of crime, when it was announced by the IBGE that 63% of victims of physical aggression occurring in the domestic space were women (VILHENA, 2009).

They were often seriously beaten and others murdered by their intimate partners. The impunity of the aggressors encouraged feminist movements in the struggle, as evidenced by several cases in the media, such as Ângela Diniz and journalist Sandra Gomide, murdered by their companions.

At the end of the 20th century, faced with this scenario, a process of recognizing violence as a problem of society that was not just a specific problem in which victims are subjected to aggression was initiated. This contestation began with campaigns and services of various natures (SCHRAIBER, 2005).

Feminist movements already recognized the need to strengthen the autonomy and self-esteem of women in situations of domestic violence through broader attention. Therefore, they demanded the establishment of Specialized Police Stations in Assistance to Women, the creation of shelters, legal counseling services and psychological and social assistance services. In 1982, in Rio de Janeiro, voluntary work by feminists began with S.O.S Mulher and, in 1984, the installation of a service to assist victims of violence. In 1986, the first Women’s Police Station was established in the state. In São Paulo, in 1983, the first State Council for the Status of Women was created.

In the same year, and also under the influence of the women’s movement, the Ministry of Health implemented the Program for Integral Attention to Women’s Health with the objective of serving the female segment at all stages of life and guaranteeing the principle of equity, not only in attendance and access to the services provided (GOMES, 2009).

In the same state, in 1985, one of the first measures was taken that represented an effective intervention of the State in the face of violence against women: the Police Station for Specialized Assistance to Women – DEAM, with the function of receiving and investigating the news and complaints of women.

In 1986, the Legal Guidance Center (COJE)[2] was created to provide legal guidance to women, inform them about their rights and refer them to the appropriate place to take legal action. And, later, the Coexistence Center for Women Victims of Domestic Violence (COMVIDA)[3] was created, which was the first shelter in the country with the function of sheltering women at risk of life, in a secret location (PAVEZ, 1997).

The Federal Constitution of 1988 represented a milestone in the achievement of women’s rights, especially with regard to equal rights and duties between men and women. CF/88[4] equalizes men and women before the law in their rights and obligations, that is, there is equality with regard to decisions made regarding their offspring and sustenance, there is an end to the leadership of the conjugal society that was exercised only by the man, there is the possibility for women to continue with their maiden name after marriage, there is a free choice of family planning, reproductive and sexual rights, such as sterilization methods and the right to abortion in case of risk to the mother or in cases of rape, among others.

In addition to these family rights, CF/88 discusses equal rights at work, such as maternity protection, equal pay between men and women for the same service and guarantee of employment for pregnant women. From this right, women also gained political voice, as it is up to the parties to reserve thirty percent and a maximum of seventy percent for candidacies of each sex (ALVES, 2008).

In 1990, according to Miranda (2007), the Hotline was another instrument of fundamental importance implemented in the fight against cases of domestic violence against women. The initial demand for this service was to receive anonymous information of a criminal nature from the population that would help the police forces to clarify crimes and forward them to public security agencies.

In 1994, the Convention of Belém do Pará demanded an effective commitment from the States to eradicate gender violence. To this end, it is proposed the creation of laws that aim to protect women’s rights, the restructuring of sociocultural patterns, the encouragement of personal training, as well as the creation of specific services to care for women who have had their rights violated. (MIRANDA, 2009)

After 20 years, the latest data from the Basic State Information Survey – from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics/IBGE-2012, of the 26 Federative Units in Brazil with a managing body, only 10 have a State Policy Plan for Women (PEPM)[5], of which most states are in the North and Northeast regions. These data demonstrate how much Brazil needs to advance.

In 2005, another step was taken with the “call 180” service created by the Secretariat of Policies for Women of the Presidency of the Republic (SPM-PR). It is aimed at assisting women in situations of violence to serve as a direct channel for guidance and public services with toll-free calls. In the first half of 2017, “Ligue 180” received more than 560 thousand calls.

3.1 MARIA DA PENHA LAW

Law 11,340, also known as the Maria da Penha Law, was created in 2006 (BRASIL, 2006) and is considered a historic milestone in the struggle to defend the rights of Brazilian women. According to the United Nations, the Law is the third best and most advanced in the world with regard to tackling domestic and family violence against women (BRASIL, 2018).

This is due to the definition and consideration of violence against women as a violation of human rights: before it, it was seen only as a crime of “minor offensive potential”, as stated in Law 9099/95.

In this sense, the Maria da Penha Law (Law nº 11.340/2006) is characterized as a result of the collective effort of women’s movements that fought to combat domestic violence in the family. It aims to typify and punish any act of violence through various mechanisms. It is evident, therefore, that after the emergence of the aforementioned law there was a broader view on the subject. (BRASIL, 2006)

Campos (2008, p. 49) argues that she:

[…] Cria mecanismos para coibir a violência doméstica e familiar contra a mulher, nos termos do § 8o do art. 226 da Constituição Federal, da Convenção sobre a Eliminação de Todas as Formas de Discriminação contra as Mulheres e da Convenção Interamericana para Prevenir, Punir e Erradicar a Violência contra a Mulher; dispõe sobre a criação dos Juizados de Violência Doméstica e Familiar contra a Mulher; altera o Código de Processo Penal, o Código Penal e a Lei de Execução Penal; e dá outras providências.

This Law became known as a result of many struggles of the Brazilian feminist movement. She was given the name “MARIA”, a name so popular in the Brazilian context, that she became a friend of several women. As stated earlier, this name is a tribute to the struggle faced by pharmacist Maria da Penha Maia Fernandes, from Ceará, who was the victim of various forms of violence practiced by her then-husband, a university professor, who was shot and electrocuted.

For 20 years, Maria da Penha, a survivor of several attacks, was left paraplegic, but fought in all instances for justice to be done against her ex-husband. She had to trigger international bodies to denounce the impunity of Brazilian justice.

Research indicates that, after this Law, 98% of the Brazilian population has heard of it and 70% consider that women suffer more violence at home than in public spaces. According to the National Council of Justice (CNJ), in 2016, more than 212,000 new cases were registered on cases of domestic and family violence. In addition, more than 280,000 protective measures were issued to protect women in situations of violence.

In order to develop a Network for Assistance to Women, in 2007, the Federal Government launched the National Pact to Combat Violence Against Women, with the aim of articulating Brazilian states to commit to developing services using resources from the Secretariat of Policies for Women.

In 2011, the National Pact was updated with the need to renegotiate policies to combat violence against women in the States. To continue the process, between 2013 and 2014, 18 units of the federation reaffirmed their commitment to the National Pact and signed the term of adhesion to the Programa Mulher: Viver sem Violência.

The Secretariat of Policies for Women-PR is responsible for coordinating the “Mulher, Viver sem Violência” Program launched on March 13, 2013. This program seeks to further consolidate existing public services aimed at women in situations of violence. Through the integration of several areas such as public security, social assistance network, health, justice and promotion of financial autonomy, it is believed that it is possible to improve assistance to victims.

It was transformed into a Government Program through Decree No. 8086, of August 30, 2013, to collaborate with the Ministries of Justice, Health, Social Development and Fight against Hunger, and Labor and Employment. Between 2013 and 2014, 26 units of the federation (with the exception of the state of Pernambuco) joined the Programa Mulher: Viver sem Violência, of which 18 signed the term of adhesion through a public act.

In 1985, with the end of the dictatorship, the National Council for Women’s Rights (CNDM) was created, composed of 17 counselors appointed to the post by the Minister of Justice. This council aimed to promote, at the national level, policies to ensure women’s conditions of freedom, equality of rights and full participation in the country’s political, economic and cultural activities. However, in the 1990s, during the Collor de Mello government, the CNDM lost some of its political strength, which was only recovered during later administrations, although losing some of its original essence (MIRANDA, 2009).

The Federal Constitution of 1988 represented another milestone in the achievement of women’s rights, especially with regard to equal rights and duties between men and women. In the 1990s, there were significant changes in Brazil regarding the issue of women, as the country had to assume internationally agreed commitments.

Regarding the commitment to creating norms and promoting racial and sexual equality discussed around the world at the various World Conferences on Women:

As questões de gênero, antes eram relegadas ao domínio doméstico das jurisdições nacionais, mas depois do envolvimento dos organismos internacionais, essa questão passou a ser vista no âmbito das considerações globais. Inicia-se, com isso, um processo internacional de codificação dos direitos das mulheres. Nesse sentido foi elaborada uma plataforma a ser seguida pelos governos, onde os mesmos assumem uma série de compromissos. (BRASIL, 2015)

However, it is only in the first decade of this century that the Brazilian State assumes a more explicit commitment to the issue of public policies for women.

3.2 NATIONAL POLICY PLAN FOR WOMEN

An important milestone for the inclusion of the women’s issue in the decision-making process of public policies was the creation, in 2003, of the Secretariat of Policies for Women (SPM). From the creation of this Secretariat, women started to have a significant space where their demands would be dealt with with a greater commitment on the part of the Federal Government. The objective of the SPM is to fight for the construction of equity in Brazil and to act as a valuer of women, seeking to include them in the process of social, economic, political and cultural development of the country (BRASIL/SPM, 2015).

With the SPM, issues related to the issue of women in the labor market also acquired greater public status. The SPM operates in three main lines of action, namely: (1) Labor Policies and Women’s Economic Autonomy; (2) Combating Violence Against Women; and (3) Programs and Actions in the areas of Health, Education, Culture, Political Participation, Gender Equality and Diversity. Today, the National Council for Women’s Rights is part of the structural composition of the Secretariat of Policies for Women and is composed of representatives of civil society and government (BRASIL/SPM, 2015).

The creation of the SPM was a great advance for the feminist movement, as it represented an important means for initiating the construction of gender policies. The SPM also made possible several new participatory spaces, such as the National Conference on Policies for Women and, as a result of this, the National Plan for Policies for Women.

An important instrument in the elaboration and monitoring of policies for women is Transversal Management (or Gender Mainstreaming), because through it it is possible to execute and evaluate policies in a non-hierarchical way, encompassing several factors that are directly or indirectly part of the implementation and maintenance of the National Policy Plan for Women, although this transversality is still a challenge in the current Brazilian Public Administration (PINTO, 2006).

According to Bandeira (2005, p. 5):

Por transversalidade de gênero nas políticas públicas entende-se a ideia de elaborar uma matriz que permita orientar uma nova visão de competências (políticas, institucionais e administrativas) e uma responsabilização dos agentes públicos em relação à superação das assimetrias de gênero, nas e entre as distintas esferas do governo. Esta transversalidade garantiria uma ação integrada e sustentável entre as diversas instâncias governamentais e, consequentemente, o aumento da eficácia das políticas públicas, assegurando uma governabilidade mais democrática e inclusiva em relação às mulheres.

Transversality must be ensured at all levels of government, such as Ministries and Secretariats, and it must also be present in civil society movements so that gender equity becomes a reality, as the single effort of the SPM is not enough. Therefore, the integration of governmental and social bodies is necessary, since the problem of gender inequality is complex and crosses several areas. Brasil (2015, p. 35) argues that:

A transversalidade permite abordar problemas multidimensionais e intersetoriais de forma combinada, dividir responsabilidades e superar a persistente ‘departamentalização’ da política. Na medida em que considera todas as formas de desigualdade, combina ações para as mulheres e para a igualdade de gênero e, dessa forma, permite o enfrentamento do problema por inteiro. (BRASIL, 2015)

In this public policy process, the SPM acts as a horizontal coordinator. Therefore, the institution has the role of articulating all the bodies involved with the issue of women and coordinating the policy implementation process, always monitoring and evaluating the results (BRASIL, 2015).

To guide or structure public policies for women and the planned actions and goals, the National Plan of Policies for Women (PNPM) is prepared. For the political and institutional achievement of this plan, it is necessary to hold National Conferences on Policies for Women. These Conferences take place in all spheres of Government (Union, States and Municipalities) and are nationally agreed.

The Conferences for Women aim to bring them together with their demands in all corners of the country and, in this way, develop guidelines and actions according to the needs presented by them. In this way, in a participatory and democratic way, in a dialogue between civil society and the Government, the National Plan is prepared.

The first National Conference on Policies for Women was held in 2004 and was held by the Secretariat of Policies for Women in partnership with the National Council for Women’s Rights. The second Conference was held in 2007 and the third in 2011, giving rise to the III National Policy Plan for Women, which will be analyzed below. The III National Plan of Policies for Women (PNPM), effective from 2013 to 2015, has a series of proposals with the objective of improving women’s lives and achieving equal rights for women.

The Plan has ten chapters, namely: (1) Equality in the world of work and economic autonomy; (2) Education for equality and citizenship; (3) Women’s comprehensive health, sexual and reproductive rights; (4) Tackling all forms of violence against women; (5) Strengthening and participation of women in spaces of power and decision-making; (6) Sustainable development with economic and social equality; (7) Equal land rights for rural and forest women; (8) Culture, sport, communication and media; (9) Confronting racism, sexism and lesbophobia; (10) Equality for young and old women and women with disabilities (BRASIL, 2015).

The PNPM also has a chapter on the attributions of the body responsible for its management and monitoring, in this case the SPM, as well as its partners. The PNPM also contains the general and specific objectives, goals, lines of action and the action plan, the latter being detailed in actions, responsible bodies and partners.

It is guided by the National Policy for Women which provides for: women’s autonomy in all dimensions of life; effective equality between women and men in all spheres; respect for diversity and fight against all forms of discrimination; secular character of the State; universality of services and benefits offered by the State; active participation of women in all phases of public policies; and transversality as a guiding principle of all public policies (BRASIL, 2015).

It is prepared in accordance with the Multiannual Plan (2012-2015) and its actions can be implemented directly by the Secretariat of Policies for Women or not, and other government bodies are also responsible for its execution (BRASIL/SPM, 2013).

Regarding the Management and Monitoring of the PNPM, the SPM acts as the coordinator of the management and monitoring of the Plan. It is also up to social movements and civil society to monitor the actions, exercising social control over the proposed policies. There is also the Plan Coordination and Monitoring Commission, which has 32 government bodies and 3 representations of the National Council for Women’s Rights.

In addition, eventually, some guests are part of the Commission, such as the United Nations, the International Labor Organization and representatives of Policy Organisms for Women in Municipalities, States and the Federal District. In short, the policies proposed by the National Plan seek to dialogue with all governmental spheres and with civil society (BRASIL, 2015).

The PNPM has 199 actions, distributed in 26 priorities, which were defined based on the debates established at the I National Conference on Policies for Women. They were organized by a Working Group, coordinated by this Secretariat and composed of representatives from various ministries, such as Health, Education, Labor and Employment, Justice, Agrarian Development, Social Development and Fight against Hunger, Planning , Budget and Management, Mines and Energy and Special Secretariat for Policies for the Promotion of Racial Equality (SEPPIR), National Council for Women’s Rights (CNDM) and representatives of state government spheres – represented by Acre – and municipal spheres represented by Campinas/SP .

4. ASSISTANCE SERVICES FOR WOMEN: WOMEN’S DELEGACIA

For Pasinato and Santos (2008, p. 34), the Women’s Police Stations “constitute the main public policy to combat domestic violence against women”. Thus, the implementation of Specialized Police Stations in Assistance to Women is an important milestone, as it shows that the State recognizes that violence against women must be discussed widely and not only in the private sphere or in interpersonal relationships.

It is a social issue that needs public actions both in the area of security and in the area of health due to the consequences it causes. For Massuno (2002), the Police Station Specialized in Assistance to Women represents an agency eminently focused on combating violence against women.

The first Women’s Police Station was created in Brazil, in the city of São Paulo, on August 6, 1985, under Decree No. 23.769, based on the idea that, to deal with violence against women, it would be more appropriate to female police officers because they are more prepared than men. (MASSUNO, 2002)

It is important to emphasize that the Specialized Police Stations in Assistance to Women face structural problems. At this point, Pasinato and Santos (2008), when commenting on the operating conditions of the Women’s Police Stations, emphasize the lack of human, material and financial resources.

Debert, Gregori and Piscitelli (2006) warn of the unpreparedness of the agents who work in the Women’s Police Stations. It is noticed that, in most cases, these professionals are not offered a specific qualification to perform their duties in a police station that receives raped women.

Thus, it is noted the presence of deficiencies and precariousness in the Specialized Police Stations in Assistance to Women, requiring, among other measures, greater training of the people who work in these Police Stations, as well as greater financial investments by the State.

4.1 CONCEPTUALIZATION OF THE SHELTER HOUSE

The National Guidelines for Shelter for Women in Situations of Violence refer to the set of recommendations that guide the sheltering of women in situations of violence, as well as the flow of care in the service network, including the various forms of violence against women (trafficking of women, domestic and family violence against women, etc.) and the new methods of sheltering (temporary short-term shelter, shelters, occasional benefits, shelter consortia, etc.).

Shelter services, in their most diverse modalities and dimensions, have broader concepts. They relate to a list of services and benefits that must be offered by the government. In this sense, not only are shelter services considered (shelters, foster homes, shelters, transit and support houses, etc.), but also programs offered by other policies (such as social assistance) that ensure the physical, psychological and social well-being of vulnerable and at-risk populations.

Thus, it is extremely important that there is a good dialogue between the policy of rights for women and that of social assistance, as the latter has eventual benefits for cases of social vulnerability that can and should also be destined for women in situations of violence, either as an alternative to shelter, or as a supplement or income transfer in situations that require shelter.

4.2 REFERENCE CENTER

Violence against women is a multidimensional problem that enables the expression of the social issue and is configured in the historical concept of gender violence, that is, it brings the result of oppression and domination of men, violating the physical, psychological and moral integrity of women. By bringing this issue to the public, it is necessary for the State to contribute to the confrontation of women victims of violence by creating legal and structural mechanisms in order to curb and prevent gender violence.

The reception in the Reference Center that a policy of combating violence against women is made, from the protection carried out by the Maria da Penha Law, Law 11.340/06 that is enacted in principles and care network for women who suffer from violence.

The Reference Center plays its role as an articulator and host in situations of violence which, in many cases, are addressed by gender inequality, discrimination by ethnicity, social class and others. Therefore, information is published to work on public policies that must be expressed and confronted with violence. It is worth noting that the great achievements of women will be implemented to strengthen protective measures based on the effectiveness of the judicial system.

The Reference Center is the place where services are provided for women who suffer from violence, establishing measures to protect women at risk with the insertion of public policies so that they can break this cycle of violence. Its main objective is to contribute to preventing, punishing and eradicating violence against women.

This place provides, in addition to the simple service, interaction, recovery, improvement of self-esteem and autonomy. In addition, it counts on the participation of professionals to accompany the woman until she restores her healthy daily life with qualified and humanized care (ALVES; VIANA, 2008).

The Reference Center is therefore of great importance for providing assistance to women and for combating violence perpetrated against them. In this way, it is an institution that assists women victims of violence, where they seek information and follow-up from professionals to guide them on welcoming as a principle, as well as on the concept of policies to combat violence against women, according to the general guidelines for the implementation of services in the care network for women in situations of violence (BRASIL, 2011).

In this institution, programs of activities are offered for the prevention and confrontation of violence against women, aiming at the rupture of the situation of violence and the construction of citizenship through global actions and interdisciplinary care with professionals such as: psychologist, social and legal assistant, guidance and information for women victims of violence suffered by aggressors where they seek to interrupt the cycle of violence and protect women.

Given this context, this work becomes relevant to verify the perception of users in this Center in which professionals must play the role of articulator of services, in the governmental or non-governmental sector that interact in the networks of care for women in situations of vulnerability society in terms of gender.

In this sense, studies must be based on power relations that go beyond the legal sector, in order to understand the social dynamics that occur in social struggles that seek to result in a new mode of production. There is, therefore, a concern to reduce this side of power in the expression and that it be less in the legal, produced in real, on websites with disclosure so that it can be worked on to soften this sovereign relationship.

The document of the SPM’s Network to Combat Violence Against Women discusses the concept of Combating Violence Against Women, emphasizing the articulated action between governmental and non-governmental institutions/services and the community, aiming at the development of effective prevention strategies and policies that guarantee the empowerment and construction of women’s autonomy, their human rights, the accountability of aggressors and qualified assistance in situations of violence.

Therefore, the confrontation network aims to implement the four axes provided for in the National Policy to Combat Violence against Women – combat, prevention, assistance and guarantee of rights – and to deal with the complexity of the phenomenon of violence against women.

The network to combat women in situations of violence at the national level consists of actions and services offered. The Reference Center must be prepared to assist these women victims of violence, maintaining a physical and adequate structure, with trained professionals, etc.

The Reference Center is a space for psychological and social reception/service, with guidance and legal referral to women in situations of violence. The Center provides the necessary means to overcome the situation of violence that has occurred, contributing to the strengthening of women and the rescue of their citizenship, specifying the functioning that occurs within the Institution, through:

- Provide counseling in times of crisis to give an effective response to minimize the traumatic effect of violence;

- Ensure psychosocial care with the aim of promoting the self-esteem of women in situations of violence and assisting them in the search for protective measures and overcoming the impacts suffered by violence;

- Legal advice and follow-up; the professional is prepared to advise on which procedures are appropriate within the legal system and which administrative measures in the police aspect;

- Organize prevention activities through the promotion of lectures that show cases of women who were The objective is that, through this awareness, they can break down this prejudice that underlies discrimination and violence against women;

- Professionals must be qualified and must continue to invest in information at the Centers;

- Articulate the service network for women in the area, guaranteeing integrality and humanization in the participation of support work.

Therefore, the Reference Centers are articulated by public policy bodies for women victims of violence and, being a “reception” space to receive them, they have special public policy equipment for the prevention and confrontation of violence against women, in addition to being administratively linked to the body that manages policies for women in the Municipality where they are located (BRASIL, 2006).

Through studies carried out based on the Reference Center, it can be seen that the vast majority of complaints are made by young women, with incomplete education, low income and who lived with the main aggressor.

Thus, it appears that the role of women continues to be submissive in relation to patriarchy. This context of devaluation of women and the absence of their rights are the main factors that drive the struggle to prevent, punish and eradicate this violence.

There are many reports of victims who gave up their rights due to the feeling of love for their partner or the option to keep the home in the hope that their partner will change. In addition, there is the financial factor, fear, emotional dependence and the embarrassment of having your life in the analysis of studies based on withdrawal and criminal action.

Therefore, different types of violence related to physical, psychological, sexual, property and other aspects are verified. The woman who suffers any type of violence may find it difficult to insert herself in the social environment, at work and in universities. It is important, therefore, that the professionals of the Reference Center monitor the victims through listening, from different perspectives that make it difficult to identify the cases and types of violence suffered.

With the complexity of the demand of women victims who are taken to face and strengthen the overcoming, in the certainty of changes, the professionals who work in the care become partners in this difficult situation of the victims, and have the mission to favor the integral reception of them. To cope, the institution is a space formed by multi-professional teams in the areas of Social Work, Psychology and Legal Counsel.

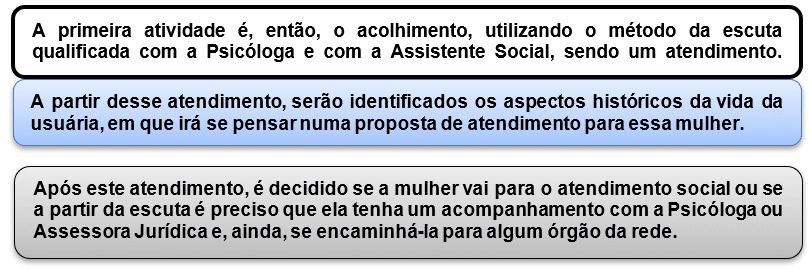

The first step to be carried out will be the service at the reception in which a form will be filled out so that, later, the victim will be referred to the service with a Social Worker who will do the reception in a room with individual listening.

The reception will start, therefore, from the day the victim looks for the Reference Center to be referred for assistance with the professionals of the Center depending on the seriousness of the case and the availability of professionals. At the beginning of the service, it is up to the professional to observe the report of the situation of violence experienced by the victim. Afterwards, information about the Maria da Penha Law, about the operation of the Reference Center and the other entities that make up both Networks will be provided.

Based on the reports heard by the women, their immediate needs are identified and then a joint plan can be drawn up so that the situation of violence can be faced. In this context, the role of the professionals at the Center is to reflect with the victims about the situation they are going through in the present, in addition to discussing ways to protect themselves and achieve their rights and protective measures. Victims are advised, even if they cannot get out of the situation of violence, not to stop being users of the Reference Center.

With several alternatives that are discussed to face or reduce the situation of violence, women decide what they want or can do, as they are the ones who have to take the first step to put an end to violence, and it is up to the Reference Center to help them .

Many victims are referred to the Women’s Police Station by a friend or a neighbor who can also answer their questions. There, they can learn about the Maria da Penha Law, about the resources offered by the Reference Center or by other facilities of the Secretariat/Coordination of Policies for Women.

The next step is the referral to the psychologist and then to the Legal Counsel. The psychologist will follow up in individual listening and will begin to study the whole situation and work on the emotions of the victim who suffers from violence. It is important to note that all information given by women is noted.

With this information collected at the reception, information given by the women to the other professionals will be added, which will form their dossiers. When they return to the Center with the incident report, if they want, the process continues. There are cases where women do not register the bulletin, but want information on how to act. However, as they are afraid of their partner, they do not report the violence, but even so, they want support to face it.

In view of the history and types of violence, cases are handled differently through the work carried out by social workers in the Centers, as it does not only include care, but a welcoming. At this time, women may present a state of disturbance and difficulties in clearly stating their problems. It is therefore up to the social worker to listen and talk to them about the event that took place.

There will also be referrals to monitor and verify the results of female victims. The social worker performs individual consultations, as they need to be scheduled. Its function is to identify, based on the women’s reports, their main needs and demands for referral. Then, it passes on to the psychologist’s care who, unlike the social worker whose objective is to meet the objective demands of women who live in situations of violence, the psychologist’s role is to work with the subjectivities of the women’s reports by providing individual consultations.

The beginning of treatment is to lead women to reflect on the situation of violence in which they live, on their relationship with their partner and other family members, as well as to think of ways to face and get out of this situation of violence. The women arrive at the Center at different stages of the violence event, and most of them are indicated by their friends or neighbors, because their partner is afraid of making the complaint.

Women seek legal advice in relation to reporting violence in two cases, namely: in the case of separation resulting from or regarding their rights. Legal advisors inform the entire procedure of legal cases, the protective measure and the criminal process of representation against the aggressor and its consequences. Referrals to the Coping Network are carried out by legal advisors.

In order to accompany the women in the Centers, which will be carried out by the legal advisor, it is understood to prepare the hearings in the Courts or even physically accompany them, when possible.

The Reference Center works to the extent that it can contribute to the reduction of social injustices, especially those that target people with a lack of information about their rights, seeking to improve the service and the satisfaction of both professionals and women. Adding also to these changes that are described without the intention of delving into the issues that started them from the historical context of the reports of victims in situations of violence.

The path taken by each woman represented an advance, as they motivated other women to seek help in the services of the Reference Center. It is known that there are still difficulties along the way, such as the issue of women having their position of social authority that fulfills traditional gender roles; access to information on the Maria da Penha Law; lack of knowledge about forms of violence; and the recognition of institutions that are part of the network to help women in situations of violence.

For these reasons, the fragility with the link between the services and their actors is highlighted, which resulted in a misunderstanding of referrals, due to failures in communication and articulation between the network of confrontations of women victims of violence, which results in difficulties in care and judicialization of violence. This situation results in conditioned care to the people who provide services and not to the services, and reiterating a void in this situation that can bring complications in the lives of women.

The institution that can support this situation of women is the Police Station, which will act as a “gateway” to the network’s services, acting as a protection of rights that can streamline and facilitate the work that seeks to be shared (BEIRAS et al., 2012).

Policies and laws on gender violence. Critical reflections. With the results obtained, questions are asked about how to direct these training actions for services and the community, such as the importance of the Maria da Penha Law, which has a proposal for shared work in networks.

For Pasinato (2010), the lack of integration between the network means that the assistance measures that the woman needs are not applied, in addition to the lack of coordination with social programs and policies for the referral of her and her family members. Apparently, it is possible to say that the network can become fragile, becoming a fragile and unstable network because there is no resistance policy. (PASSINATO, 2010)

According to Beiras et al. (2012), men are part of the problem of violence against women and should be included in the construction of strategies to solve this problem. The Reference Centers must pass on the importance of the Maria da Penha Law to women, strengthening the bond and its articulations. (BEIRAS, 2012)

In this way, there will be constant training that is committed to the proposals of the Maria da Penha Law. These services have contributed to give visibility to the theme, as well as in an attempt to deconstruct stereotypes about men, women, the family, etc. Despite the great media disclosures, little that has been demonstrated so far regarding the reality of public services provided, it is clear how far society is from actually implementing the Maria da Penha Law.

4.3 ESPERANÇA GARCIA WOMEN REFERENCE CENTER IN TERESINA/PI

The present study had as its research scenario the Esperança Garcia Reference Center (GREG)[6] which is a non-governmental body. It is located at street Lizandro Nogueira, 1796, center/north in Teresina-PI. It was inaugurated in March 2015 through the Women’s Secretariat.

The objective of the Center is the reception, care and defense of women in situations of domestic and family violence. He has been developing a very relevant work in the defense of Teresinense women in partnership with the Archdiocesan Social Action (ASA).

The name of the organ is a tribute to “Esperança Garcia”, a slave woman, who became known for having written a letter addressed to the president of the province of São José do Piauí, for the mistreatment suffered by her and her son by the overseer of the cotton farm In the 1770s, when women, mainly slaves, had no voice or time, this woman dared to do something different and fight for her rights.

The objective of the Center is, therefore, to make it possible to overcome the situation of violence and the construction of citizenship, through actions of psychological, social, legal and guidance and information for women in situations of violence. In addition, it provides the necessary assistance to overcome violence, contributing to the empowerment of women and the recovery of their citizenship. (SILVA, 2019)

4.3.1 ACTIONS OF THE REFERENCE CENTER FOR WOMEN ESPERANÇA GARCIA FOR THE PREVENTION, COATING AND AUTONOMY OF USERS VICTIMS OF VIOLENCE IN TERESINA/PI

It is known that overcoming the condition of violence against women depends a lot on the effectiveness of laws and the implementation of efficient Public Policies. In this direction, until there is no knowledge on the part of society on how to prevent, face and overcome violence, there will be women who will be unaware of their rights, being deprived of the rupture of the violence suffered. (SILVA, 2019)

The Center offers a very important service, given the situation of violence in which women find themselves. The municipality of Teresina did not have a Reference Center while in some capitals there was already due to the Maria da Penha Law. Only seven years after the creation of that law, the Reference Center was created in Teresina/PI. According to Silva:

O serviço ofertado pelo Centro de Referência Esperança Garcia é a referência para a mulher que está em situação de violência e que a partir dali, ela seja encaminhada e acompanhada dentro da Rede de Atendimento. O espaço pretende fortalecer ainda, a articulação entre as instituições que integram a rede, a fim de desenvolver melhores estratégias de integração entre os serviços. (SILVA, 2019)

In the field of action, the services offered are given as support in order to refer each case to the professionals who will be able to accompany the woman victim of violence, through protective and preventive means. The age group of women who are generally served is between 18 and 59 years old. The space has a multi-professional team specialized in the areas of Social Work, Psychology and Legal in specialized care for women in situations of violence.

The Reference Centers are essential spaces, especially in a given conjuncture, for the prevention and confrontation of violence against women, since their objective is to promote the rupture of the situation of violence and the construction of citizenship, of their self-esteem, of autonomy for through its actions and interdisciplinary assistance (psychological, social, legal, guidance and information) to women in situations of violence. (SILVA, 2019)

Considering that violence against women is an increasingly visible practice, constant training of professionals working in the institution is necessary, in the sense of better foundation for professional practice, which will act in a direct way based on science.

In this way, the actions carried out follow the guidelines drawn up in the Technical Standard for the Standardization of Reference Centers for Assistance to Women in Situations of Violence, which was prepared by the Special Secretariat for Policies for Women. They must play the role of articulators of the services of governmental and non-governmental organizations that are part of the service network for women in situations of social vulnerability, due to gender violence (SILVA, 2019)

As for the occupation of these women assisted by the Center, most are housewives and with low education, who present a situation of vulnerability, and still survive historically by the sexist culture. In this sense, the institution comes to welcome and protect women victims of violence. In this context, the actions that are offered at the Esperança Garcia Reference Center are presented below:

O Centro de Referência Esperança Garcia estabelece articulações com os Centros de Referência de Assistência Social – CRAS, onde a equipe multiprofissional apresenta-se até um CRAS numa determinada comunidade/território para divulgação e apresentação do Centro, dos seus serviços, dos tipos de violência, pois muitas instituições não o conhecem. Em datas comemorativas relacionadas às mulheres, como por exemplo, em agosto com o aniversário da Lei Maria da Penha, em março com o Dia Internacional da Mulher, o trabalho do Centro é intensificado com panfletagem em praças, nos shoppings das cidades, a equipe multiprofissional participa de palestras que a Rede de Atendimento à mulher proporciona para a sociedade civil, entre outras atividades. (SILVA, 2019)

In addition, women participate in various activities such as massage therapy, cinema, haircuts and reflection groups to strengthen themselves and improve their self-esteem. Daily, several women with cases of violence are received and who seek to interrupt this cycle, in addition to seeking protection and care. Regarding the interventional care procedure, it happens as follows:

In order to have quality care and to understand the specificity of each woman, team meetings, case studies, monitoring of this woman through calls, home visits and, if necessary, even institutional visits to the Health Network are held. Assistance to women and the construction of instruments to assist these women who arrive at the Reference Center.

In this way, the Service Flow can be cited as instruments, where the bodies that make up this Service Network are cited to offer a broader view to women about the spaces in which they can be welcomed to face and overcome violence. (SILVA, 2019)

With regard to actions for women’s autonomy, the services that the Esperança Garcia Reference Center for Women in Situations of Violence promotes are:

Table 2- Actions for Women’s Autonomy

| Reflection groups with women accompanied by the Center, where topics relevant to their context are discussed and analyzed. Women will be able to exchange ideas, talk and strengthen each other; |

| Café com Mulheres, which is yet another proposal with the objective of giving women the opportunity to listen to each other, promotes reflection and dialogue. It takes place every Wednesday for women interested in the service, for the Network for Assistance and Confronting Violence against Women in Teresina and other guests; |

| Other activities have already been thought of as massage therapy that seeks to make her think about her self-esteem; belly dancing so that the woman thinks about her sensuality exploring her body; cinema, as a moment of leisure; |

| The Hidden Beauty is a proposal for the woman assisted by the Center to have a moment of beauty, with haircuts, manicure, in addition to a health service with blood pressure measurement and blood glucose level. |

Source: Silva (2019) Data organized by the author.

In view of the above, it was evident that the Esperança Garcia Reference Center in Teresina/PI, through its actions, allows women to perceive themselves as victims of violence and that, based on this perception, they can review this situation. It is through discussions that the relationship of subordination of many women within society is verified, thus creating instruments of defense in it. Perceiving themselves as violated, but, at the same time, as subjects of law, women start to develop capacities to face and rescue their self-esteem and autonomy.

5. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

It is concluded, therefore, that violence against women is the result of a historical construction, being subject to deconstruction. This close relationship with the categories of gender, class and race/ethnicity and their power relations can be considered as any and all conduct based on gender, which causes or is likely to cause death, damage or suffering in the areas: physical, sexual or psychological. women, both in the public and private spheres.

From the bibliographic surveys of this research, it was possible to conclude that the phenomenon of violence against women has advanced at a galloping pace, while its confrontation progresses slowly. This entire network that characterizes it will still take a long time to be deconstructed, however, it would not be utopian to believe that there is hope in the midst of chaos.

Violence against women is a public health problem of epidemic proportions in Brazil, although its magnitude is largely invisible. A work to raise awareness of the historical nature of gender inequality needs to be implemented from the beginning of school education, since gender inequality contributes to the perpetuation of unequal power relations that end up leading to violence.

The process of implementing public policies aimed at women, such as the Maria da Penha Law, as well as the creation of assistance bodies such as the Esperança Garcia Reference Center, has contributed a lot to raising awareness about the guarantee of rights and the strengthening of care in the public security, judiciary and health.

However, it is necessary to guarantee rights, in addition to creating more reference centers with multidisciplinary professional care, with professionals from the areas of Social Work, Psychology and Legal, in the sense of better guidance, support and security in addition to strengthening the defense against violence, especially the domestic one, are some urgent actions.

Thus, this research is relevant for contributing with information that will help in the reflection on care for women in situations of violence, pointing to the need for networking that strengthens defense, accountability and support for people in situations of violence. I support this, jointly between the State, non-governmental bodies and society as a whole.

REFERENCES

AGUIAR, N. F. Patriarcado. In: FLEURY-TEIXEIRA, E; MENEGHEL, SN (orgs). Dicionário Feminino da Infâmia. Rio de Janeiro: FIOCRUZ, 2015, p. 270-272.

ALVES, M. E.R. Políticas públicas para as mulheres de Fortaleza: efetivando direitos e construindo sonhos. In: ALVES, Maria Elaene Rodrigues; VIANA, Raquel (orgs.). Políticas para as mulheres em Fortaleza: desafios para a igualdade. Fortaleza: Coordenadoria Especial de Políticas Públicas para as Mulheres. Secretaria Municipal de Assistência Social. Prefeitura Municipal de Fortaleza; São Paulo: Fundação Friedrich Ebert, 2008. p. 17-27.

BANDEIRA, L. Memorial. Brasília: Departamento de Sociologia da Universidade de Brasília (UnB), 2005, mimeo.

BRASIL, 1988. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/ConstituicaoCompilado.htm. Acesso em: 5. Mai. 2020.

CFESS-CRESS. Relatório de Pesquisa.” Perfil do Assistente Social no Brasil”. Maio, 2004.

___________, Decreto nº 52.476, de 12 de setembro de 1963. Promulga a Convenção sobre os Direitos Políticos da Mulher, adotado por ocasião da VII Sessão da Assembléia Geral das Nações Unidas. Disponivel em: https://www2.camara.leg.br/legin/fed/decret/1960-1969/decreto-52476-12-setembro-1963-392489-publicacaooriginal-1-pe.html. Acesso em: Jun. 2020.

DIAS, M. B. A Lei Maria da Penha na justiça: A efetividade da Lei 11.340/2006 de combate à violência doméstica e familiar contra a mulher. São Paulo: Revista dos Tribunais, 2008.

GOMES, N. P. Trilhando Caminhos para o Enfrentamento da Violência Conjugal. [Tese de Doutorado] Escola de Enfermagem da Universidade Federal da Bahia, 2009.

GUEDES, R. N. A violência de gênero e o processo saúde-doença das mulheres. Esc. Anna Nery 2009, vol.13, n.3, pp.625-631. Disponível em: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1414-81452009000300024. Acesso em: 5. Jun. 2020.

INSTITUTO PATRÍCIA GALVÃO. Mais de 1,2 milhão de mulheres sofreram violência no Brasil entre 2010 e 2017. Disponível em: https://agenciapatriciagalvao.org.br/violencia/mais-de-12-milhao-de-mulheres-sofreram-violencia-no-brasil-entre-2010-e-2017/. Acesso em: 10. Jun. 2020.

___________, Lei Maria da Penha. Lei n.°11.340, de 7 de Agosto de 2006.