ORIGINAL ARTICLE

NETO, Dalk Dias Salomão [1], SOUSA, Nicole Moreira Faria [2], DENDASCK, Carla Viana [3], FECURY, Amanda Alves [4], OLIVEIRA, Euzébio de [5], DIAS, Claudio Alberto Gellis de Mattos [6]

NETO, Dalk Dias Salomão. Et al. Analogous labor to the slave in the brazilian textile industry. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 06, Ed. 05, Vol. 13, pp. 28-46. May 2021. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access Link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/social-sciences/brazilian-textile, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/social-sciences/brazilian-textile

SUMMARY

The institute of slavery has been present in humanity since the beginning of the existence of the human being. Slavery in Brazil has sustained the economy for centuries. Millions of Africans were taken from their homeland and placed in degrading conditions of life and work. The process of abolishing slavery was time-consuming and gradual. There were centuries of much struggle and suffering for the world to begin to realize the evil that slavery represents. Even after the abolition of slavery it was common to see the worker trapped in the field by debts, or by laws that empowered employers in relation to the employee. The objective of this research was to analyze the working conditions analogous to the slave in the Brazilian textile industry. It was carried out with bibliographic review and qualitative analysis. Due to his new clothing contemporary slave labor became invisible for some time. The factors that make it possible to commit this crime, even if in today, it is basically related to a tripod: impunity, poverty and profit. The situation of misery of the neediest population forces them to undergo types of work in subhuman conditions. These textile workers are mainly immigrants from neighboring, underdeveloped countries from Latin America. Brazil was one of the first countries in the world to recognize this type of work, and that jointly with the International Labor Organization (ILO) and oysternon-governmental entities seek to combat such criminal practice on their territory.

Keywords: Slavery, Legislation, Combat, Industry.

INTRODUCTION

The institute of slavery has been present in humanity since the beginning of the existence of the human being. Although it has presented different meanings, forms and objectives throughout history, slavery has always been marked by the domination of one another (Mota e Ramos, 1999)

For Oliveira (2011) the relationship between men began in the prehistoric phase, due to the precarious living conditions and the need for hunting, fishing and fruit collection. And it was through the exchange of experiences and collaboration between the individuals that the first tribes arose.

The institute of slavery accompanies man from the beginning of the human race, as has already been said, having evidence of his existence in various moments of humanity and in countless forms. For example, in the holy Bible (the main book of Christians), we find numerous cases of slavery cited throughout the gospels. Slavery, at that time, was based on servitude by debts or work resulting from the subjugation of the loser by the winner, among others (Oliveira, 2011).

With the use of slavery for heavier jobs, people like the Greeks have managed to develop philosophy and the arts like no one else. Concomitantly with commercial production, there was a great expansion of artisanal and agricultural production channeled by the export and import trade (Oliveira, 2011).

For Silva (2010), as in Greece, Rome used slave labor, and it was during the period of the empire that slavery peaked, reaching a total of 30% of Roman society.

There were many ways to become a slave in Rome, as a rule every son of a slave mother was also a slave. Another way to enslave someone was through war, with prisoners being forced into forced labor, slavery was also used as a way to penalize individuals, such as in case of desertion of the army or delinquency of debts (Silva, 2010).

The society of the Middle Ages was formed by feudal lords, clergy and servants. In this period slavery was not the main means of labor, being the substitute servants of slaves, suffering terrible living and work conditions (Silva, 2010).

Although the servants were not considered objects, their legal situation was not so different from the slaves, since they were treated as mere accessories of the land, suffering impositions of a personal order, not having their right to come and go guaranteed and even prohibition to contract marriage without authorization (Silva, 2010).

Bringing the focus to our country is important to point out that slavery was present in the historical evolution of this great part of land. Initially known as Santa Cruz de Cabrália and later from Brazil, it was colonized by Portuguese, who when they arrived here in the year 1500, brought with them large-scale slavery, starting with the natives, tupis and Guaraníes mostly and later black Africans (Silva, 2010).

To succeed in the search for raw materials for the metropolis, the Portuguese began colonization using slavery as an extraction base. First, they used the native labor, making the barter with them that, in exchange for spices and metals, left to the Indians objects of irrelevant value such as mirrors and combs (Oliveira, 2011).

The relationship of the Portuguese crown and the natives at first was quite peaceful, however, after the Portuguese decided to occupy the territory to develop economic exploitation, relations changed. From then on the settlers began to expel the natives from their lands and subjugate them to slave labor, who suffered from physical exploitation and new diseases brought by the white man (Gorender, 1985).

Indigenous peoples suffered for a long time from slavery, however, this situation did not last for long, given several factors that slowed the exploitation of the native, such as the low population density of indigenous peoples; the tribes that became unamalike when they perceived their enslavement; the indigenous population that was eventually decimated due to exploitation and diseases previously unknown, as well as the protection received by the Jesuits (Campos, 2015).

The same protection given to the indigenous by the Jesuits was not given to blacks, so their enslavement was practically a consensus between church and crown (Fausto, 2004). One of the main justifications for enslaving the African black was that this practice was already common in Africa, also based on scientific theories that affirmed the inferiority of the black race, because people of low intelligence and emotionally unstable were demonstrated, biologically destined for subjection, creating one of the greatest forms of prejudice ever seen (Mattos, 2015).

Slavery in Brazil has sustained the economy for centuries. Millions of Africans were taken from their homeland and placed in degrading conditions of life and work. According to (Soares, 1860), approximately 371,615 slaves entered the country.

Initially, slave labor and the Brazilian economy were concentrated in the field, in agriculture, more specifically in sugarcane plantations located in the Northeast, being a way found by the crown of colonizing this part of the “new world”. It is important to demonstrate that in the eighteenth century, with the progressive expansion of colonization and discovery of new spaces in the interior of the country, the great mining potential of the lands was discovered, creating an intense market for the extraction of ores, such as gold, where slave labor enabled such activity (Campos, 2015).

And it was at this rate that slavery negatively marked not only the world, but also Brazil. The only justification for importing the negro was the work. They worked hours on end, fifteen to eighteen hours a day, suffered physical violence and psychology daily and were treated as objects (Pinsky, 1992).

The process of abolishing slavery was time-consuming and gradual. There were centuries of much struggle and suffering for the world to begin to realize the evil that slavery represents. There are several important moments that represent this change of thought: the proclamation of independence of the United States, which was based on the declaration of human rights; the French Revolution in 1789 that exalted the principles of freedom, equality and fraternity. It is also worth mentioning the English Revolution that, with the advent of the machine, showed that production could increase even using free work (Montenegro, 1997).

In view of this, traders and producers had to look for a way to replace slave labor. For example, in coffee plantations, slave labor was replaced by European immigrants, in the so-called settlement system (stimulus of the Brazilian state) who worked for remuneration, stipulated in the percentage of coffee production (Silva, 2010).

Even after the abolition of slavery it was common to see the worker imprisoned in the field by debts, or by laws that empowered employers in relation to the employee, through contractual obligations, such as harsh penalties, such as the arrest of the worker who was away from the farm for no fair reason or who, remaining on the property, refused to work (Silva, 2010).

Thus, it is understood that the abolition of slavery in Brazil, by the Lei Áurea, did not actually free slaves, because there was the existence of an extremely racist and prejudiced society, thus resulting in current practices analogous to slavery.

GOAL

To analyze the working conditions analogous to the slave in the Brazilian textile industry.

METHOD

The research was carried out with bibliographic review and qualitative analysis.

According to Lima e Mioto (2007): “[…]to construct a research process, relating to the definition of the methodological procedures that will guide this process, is based on the observation that several research reports”.

Qualitative research works with values, attitudes and the relationship between processes and phenomena, not measured numerically (Gerhardt e Silveira, 2009).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

ANALOGOUS LABOR TO THE SLAVE

The existence of analogous labor to the slave can be explained by the simple fact of not overcoming the old slave system, due to its cultural roots over the centuries, even after its prohibition. In addition, contemporary slavery is based on a tripod: impunity, greed and poverty, becoming necessary, not only to fight this crime like any other, but to review our justice system, consumption patterns and development models (Miranda e Oliveira, 2010).

Therefore, the world and its efforts have not yet succeeded in extinguishing slave labor, demonstrating itself as an arduous task, especially for culture and lack of compassion among men. In this way, both states and society in general should be vigilant about this kind of nonsense.

PROTECTIVE PRINCIPLES OF WORK

Legal principles are defined as a set of standards of conduct that are presented in the legal system. The principles, as well as the rules, are norms. It can be affirmed that all science is founded on principles, so the law does not escape this rule (Saraiva, 2012).

In Martins’ thinking (2011, p. 62) the principles form the pillars of law, its basis, and the principles have a much higher degree of abstraction than the norm, and its application is to concrete cases (Martins, 2011).

The principles are explained by two currents, jusnaturalistand legal positivism, the first of which puts the principles above positive law, thus prevailing under the laws. For the second the principles would be integrators of the law, filling the gaps in it (Nascimento, 2010).

Not by escaping the rule, labor law is formed by a set of principles and rules that seek to ensure better working conditions for workers, through protection.

It is important to mention a principle that, although not in the labor field, is of utmost importance for the legal system as a whole, the principle of the dignity of the human person. This principle has a moral and spiritual value inherent to the person, therefore, each person is endorsed with this precept, and this constitutes the maximum principle of the democratic state of law.

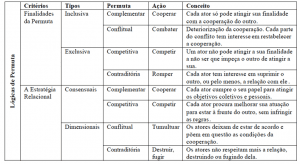

The principle of protection is the broadest and most important in labour law. This principle is one that guide severy Labor Law, aiming to protect the weakest part in the legal relationship, the worker, who finds himself unprotected vis-à-vis the employer. He seeks to give greater conditions to part hyposufficient relationship, the employee. Therefore, it provides the creation of mechanisms to reduce inequality between parties, preventing the exploitation of work and ensuring the social well-being of workers (Saraiva, 2012).

This principle is usually divided into three: the “in dubio pro operário”, that of the application of the most favorable standard and that of the application of the most beneficial condition. The principle “in dubio pro operário”, states that in the face of two or more viable interpretations, one must choose the most favorable to the worker, provided that it does not contradict the clear manifestation of the legislator, nor is it a prohibitive matter. The principle of the most favourable rule states that in the event of a conflict between two or more rules applicable in the case, one should opt for the one that is more advantageous to the worker. Finally, the principle of the most beneficial condition determines the permanence of more advantageous conditions for the worker, even if there is an imperative legal rule stipulating the contrary (Saraiva, 2012; Mattos, 2015).

Labor rights, as a rule, are indispensable by the worker. This principle is extremely important for the protection of the hyposufficient, because often the employer, through coerce, deceives or fortifies the employee to decide against his will, giving up rights already earned (Rodriguez, 2015). That is, as a rule labor rights cannot be waived by the worker, for example, one cannot give up the vacation, if this occurs such an act will be considered null (Martinez, 2015).

The Principle of The Primacy of Reality induces that labor legal relations are defined by the situation of fact, that is, by the way the services were provided, regardless of the name assigned to them by the parties (Saraiva, 2012).

A clear example is when witness testimony is proven the non-provision of individual work equipment (PPE), although there is signature of cautions for deliveries. Therefore, it is clear that one can prove the truth of the facts through witnesses, for example, prevailing such evidence to the written document, if proven the authenticity of the testimony.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS OF ANALOGOUS LABOR TO THE SLAVE

Previously slaves were seen as objects and today no more. However, although they are currently seen as people endorsed with personality, they are still subjugated to degrading living and working conditions (Mattos, 2015).

It is noteworthy that it is called “analogous labor to the slave”, since slave labor itself has been extinguished. However, despite all efforts, such slavery practices have not completely gone missing.

existence of analogous labor to the slave can be explained by the simple fact of not overcoming the old slave system, due to its cultural rooting over the centuries, despite the implementation of wage labor. In addition, contemporary slavery is based on a tripod: impunity, greed and poverty, making it necessary, not only to fight this crime like any other, but to review our justice system, consumption patterns and development model (Miranda e Oliveira, 2010).

The institute of slavery currently has a new clothing, with several denominations for analogous labor to the slave: contemporary slave labor; work in subhuman conditions, debt slavery, forced labor, overexploitation of labor, new slavery among others, forced labor, degrading labor among others (Cristova e Goldschmidt, 2012).

The various denominations set out above are due there is a lack of consensus around its concept, as well as the criteria used for its characterization of the institute. Because of this, there is a variation of elements in its conceptualization, as well as in the terms used, to refer to this type of exploitation of the worker’s labor (Cristova e Goldschmidt, 2012).

Several authors have already positioned themselves about this subject, and there was no uniform understanding between thoughts. However, it was clear in all the same feeling of revulsion at these inhuman esums of treating people, subjecting the worker to subhuman conditions (Brito Filho, 2004).

The reality of the enslaved worker is that of someone who has no option of choice, not having rights. Such workers are usually enticed in places far from the workplace, being promised a good job, with a signed portfolio, generous remuneration and other benefits. However, when the worker arrives at the workplace he is in a reality completely different from the promised one, most of the time he has to bear the expenses of travel, housing and food (Prado, 2005).

The term “slave labor” facilitates understanding by the more lay public, as it has characteristics that resemble the concepts adopted by the International Labor Organization. Such a concept was very close to “forced labour “(Audi, 2006).

In view of these concepts, we can perceive that work analogous to the slave exists, many times, due to the hyposufficiency of workers, who, in search of the minimum for their livelihood and their families, end up leaving aside their own dignity, submitting to humiliating work (Campos, 2015).

The difficulty in characterizing work in slave-like conditions not only in the academic environment, it involves public agents such as judges, prosecutors and employees of labor police stations. This difficulty has great consequences, because it ends up hindering the characterization and typification of the act, making it difficult to perceive the crime itself.

Therefore, based on the above concepts and research, one can define work in conditions analogous to the condition of slave as the exercise of human labor with restriction, in any form, which may be of the freedom of the worker, not having his minimum rights to safeguard the dignity of the human person.

The official recognition of slave-like work in Brazil took place in 1995, despite several complaints to the OIT (International Labor Organization) over the years. Despite this aggravating factor, Brazil was one of the first countries in the world to assume internationally the existence of contemporary slavery (Miranda e Oliveira, 2010).

As stated by the Ministry of Labor and Employment (MTE), analogous labor to the slave is a reality very present in the country, as demonstrated by the MTE’s own data, which reveal that between 1995 and 2010, 36,759 workers were removed from slave-like conditions (Mte, 2018).

According to the International Labor Organization, the main cause of slavery is the economic exploitation of workers, estimated to be around eight million people living in these conditions in the world. In Brazil, according to data from the Brazilian government, provided through research by the Pastoral Land Commission, there are about twenty-five thousand people working in slave-like conditions. For this amount the highest concentration is located in the northern and central-west states, and 90% of the total are composed of illiterate, 90% started with exploitation of child labor, and 80% do not even have a birth certificate (Simón e Melo, 2007).

Brazil recognized by the OIT was one of the first countries to know and combat slave-like labor. Thus, its criminalization took place through Art. 149 of the Brazilian Penal Code, which was later amended by Law No. 10,803/2003 (Brazil, 1940; 2017) It is very important to emphasize that in Brazil, through Article 149 of the CP, “analogous labor to the slave” is a genus, having other species, such as forced and degrading labor (Brazil, 2017).

Since the amendment of Article 149 of the PC by law no. 10,803, of December 11, 2003, the fight against slave-like labor has made a great advance, because it has become easier to characterize such an offense.

Analogous labor to the slave is a genus, possessing some species. For some scholars in the area these species vary, and may be forced labor, exhaustive labor, degrading work and debt.

Simón e Melo (2007) use the nomenclature “work performed under conditions analogous to slavery”, being divided into three species: forced labor, labor in degrading conditions and debt servitude. Such illegal forms of work did not have legal effects, as they are null and void, and the fight against these practices, according to Brazilian law, is carried out by criminal law.

The scholar Greco (2008) states that slave labor currently occurs when one person forces another to perform forced labor, requiring exhaustive journeys, subjecting the worker to degrading conditions, or restricting his locomotion due to debt contracted.

Silva (2010) also demonstrates that the worker’s coerity so that he does not leave work can have several natures, moral or psychological, as occurs in the threats the mental integrity of the worker, also the physical, and the worker cannot leave the workplace, because otherwise he will suffer physical punishment, often with armed surveillance.

According to Araújo Júnior (2006), work in degrading conditions is characterized by the employer’s failure to comply with basic occupational safety and health standards, which does not provide the worker’s medical examinations, does not guarantee individual protective equipment (EPI), or a place for protection of workers from the weather, in addition to maintaining accommodation without the slightest hygiene conditions and without adequate food.

There is also exhaustive work, known as strenuous work, in which the worker is tested to working conditions beyond the time limits allowed by the legislation, which can bring a lot of damage to the worker. The exhaustive journey can be conceptualized as one that goes beyond the limits of the principle of the dignity of the human person. Such a strenuous journey not only means the exaggerated number of hours, but also the inadequate pace (Campos, 2015).

The scholar Proner (2010) states that an exhaustive work day ends up negatively influencing the worker, because it deprives him of moments of leisure and education, social and family life, which can lead to psychological and physical diseases, because he becomes prone to acquiring an occupational disease.

According to Bales (2001) debt slavery is a modern form of exploitation of human labor, being the most common in the world and especially in Brazil. This condition occurs when the person is committed to work for another due to loan contracted. Employment contracts are offered with supposed labor guarantees, usually in more geographically remote places, on farms or factories, however, when arriving on the site the reality is different, deceived workers end up being enslaved, serving the contract only to deceive the worker and lead him to error.

According to Audi (2006), we can conclude that despite numerous ways presented, all forms of work analogous to the slave always have two characteristics in common: the use of coerity and the denial of freedom.

FACTORS THAT CONTRIBUTE TO ANALOGOUS LABOR TO THE SLAVE IN BRAZIL

In 1988 there was the publication of the Lei Áurea, which abolished slavery in the country. However, it was not efficient to eradicate it, due to several social factors, such as the disqualification of the labor force of the “ex-slaves” (Cristova and Goldschmidt, 2012).

The author Monteiro (2011) observed essential factors for the permanence of slave labor in the country, defining them in a tripod: impunity, poverty and profit.

As for profit, beneficiaries who use slave labor are referred to as a way to obtain high profits, in an easier way, since they do not feel obliged to comply with labor laws (Monteiro, 2011).

With regard to poverty, it is the main responsible for making many workers submit to work with slave-like conditions, since they are willing to agree even with inhuman proposals with the aim of getting out of extreme poverty and supporting their families (Monteiro, 2011).

According to the International Labor Organization, the predominant cause of slavery is economic exploitation. And together with this information, globalization in the markets can be the main reason, since it generates great competition, causing manufacturers /producers to agree to the system, producing at very low costs (Cristova e Goldschmidt, 2012).

Regarding the preponderant factors for the existence of slave labor in rural areas, Silva (2009) explains that they influence the poor region of rural workers, being an area with a large number unemployed who are convinced by the contractor through false promises, without formal labor contract or any standard established by the Consolidation of Labor Laws (CLT).

With regard to the previously explained knowledge that judicial decisions favorable to employers contribute to the maintenance of slave labor in Brazil, complements Silva’s (2009) thought that there is no strict penalty in the legislation to punish those responsible for the exploitation of slave-like labor.

Thus, with the absence of satisfactory legislation, the feeling produced is impunity, which begins to convey the idea that the wrongdoers can continue with the same criminal conduct, since they will not be serious consequences for their actions (Silva, 2009).

For the author Damião (2014), the causes of slave labor in the country are mainly the poor distribution of income and deficient education. Thus, the misery generated by the unfair distribution of income, as previously said, causes toilers to be subject to the inhuman estinies of slave labor. On the other hand, unsatisfactory education makes it easier for workers to be deceived, so that they are not able to fight for their labor rights.

In recent years, several combat mechanisms have been created, for example, the “dirty list” and national plans to eradicate analogous labor to the slave. However, despite all this history of combat and supervision, in 2017, the reform of the labor law occurred in Brazil, by law 13.467/17, which brought a setback in the subject, trivializing the practice of crime and hindering prevention (Costa, 2015).

FORMS OF COMBAT AND ERADICATION OF SLAVE LABOR CONTEMPORANEO

In Brazil, the confrontation of this crime has gained strength in recent decades, despite the delay experienced by the recent labor reform. It is known that there are countless cases of people living in conditions analogous to slavery that circumvent the precarious supervision of the State (Oliveira, 2011).

The fight and eradication of contemporary slave labor is much more difficult than they seem, since the situation is not solved simply by taking the worker out of the precarious situation and punishing the offenders. What must indeed be done is a change in the capitalist development model that, through the search for profit, ends the lives of entire families (Miranda e Oliveira, 2010).

There are several ways to combat analogous labor to the slave, both judicial and extrajudicial. However, it is public policies that influence the reeducation and cultural change of society that is the main way to overcome this social mazela (Silva, 2010).

In Brazil there is joint cooperation of several public agencies in an attempt to eradicate the exploitation of slave-like labor, namely: National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform (INCRA); Federal Police (PF); Federal Highway Police (PRF); Ministry of Labor and Employment (MTE) and Public Prosecutor’s Office (MP). It is important to note that the isolated work of only one institution is not effective. Another important way to combat it is through society itself, which, through anonymous complaints, can provide faster answers to solve such problems.

Contrary to the practice of contemporary slave labor, it is important to emphasize some authors, such as the Public Ministry of Labor and Labor Justice, which has a very important role, through repression measures, taking as an example the Public Civil Actions for Moral Damages, which seeks pecuniary reparation.

It is important to highlight the creation of the National Plan for the Eradication of Slave Labor, which was prepared by the Special Committee of the Council for the Defense of the Rights of the Human Person (CDDPH), which operates nationwide. This plan brings together entities and authorities related to the theme, which seek the creation and maintenance of a lasting public policy, being supervised by national bodies or forum dedicated to the repression of slave labor.

Another strategy used to combat such crime in Brazil originates through the National Commission for the Eradication of Slave Labor (CONATRAE), which articulates and executes initiatives. According to Oliveira (2011), this body was created in August 2003 and is formed by a collegiate linked to the Special Secretariat for Human Rights of the Presidency of the Republic, having as main function to monitor the implementation of the National Plan for the Eradication of Slave Labor.

Another form of clash is the National Pact for the Eradication of Labor Slave in Brazil. This initiative is based on international efforts, through the influence of the OIT (International Labour Organization, a ONU body). The above-mentioned pact works with the collaboration of state inspection agencies, which seek to locate and punish contemporary slave labor. According to Miranda and Oliveira (2010) this effort has been paying results, receiving support from representatives of companies that, together, mean more than 25% of the national GDP.

One of the ways to combat labor analogous to the best known slave in Brazil is the “dirty list”. This tool works as follows: a Register of Employers has been created that oblige workers to submit to conditions analogous to those of slave. This list is a public transparency mechanism of the Brazilian State, created in 2003, which seeks to disclose the names of individuals or legal entities that were caught using slave labor (Mattos, 2015).

The aforementioned register was regulated by Ordinance No. 1,234 of 2003 of the Ministry of Labor and Employment, which was later replaced by interministerial ordinance No. 2 of May 12, 2011, a document found in force (Campos, 2015). It is perceived that this form of combat becomes of great importance in the fight against contemporary slave labor, and the list of employers considered by the ONU, a reference model in the world.

In the same sense of the “dirty list” law no. 14,946/2013 was created by the State of São Paulo, which aims to seek and bar the activities of companies that have in their production chain the use of employees in conditions analogous to slavery. This law descended from a bill no. 1,034 of 2011 authored by Congressman Carlos Bezerra Junior, having a peculiarity, because it is directed to the reality of workers in the textile industry of São Paulo (Mattos, 2015).

The form of combat expressed in this law is based on the cancellation of the state taxpayer registration of the Tax on Circulation of Goods and Services (ICMS). Thus, the employer who benefits directly or indirectly from slave-like labor has revoked his registration, in addition to being restricted by the legislation proper to the subject, such punishment is presented in Article 1 of that law (Dou, 2013).

Article 4 of Law No. 14,946 of 2013 of the State of São Paulo, once the ICMS registration has been revoked, the infringing legal entity is unable to carry out activities in the same branch, even in a different place, and the partners are prevented from opening other companies of the same activity, for a period of 10 years, from the time of the impeachment (Campos, 2015).

Slave labor, although abolished for hundreds of years, remains present in society, contrary to human rights. Contemporary slavery, unlike in the old day, was no longer based on the lord’s property over slaves, much less on the business of buying and selling workers, but rather on the excessive control of the entrepreneur over the worker, using means such as coerce and coertion, with the aim of increasing his profits.

One of the sectors of the economy in which such criminal practice is very present is textiles. Existing in the major world capitals, slave labor is no longer predominantly rural and presents itself as urban, especially in sewing factories.

In the reality of urban slave labor, large numbers of people leave their homes, abandoning families in search of better living conditions and end up submitting to practices analogous to slavery, mainly out of necessity, in large textile factories (Campos, 2015).

Therefore, the textile industry is one of the great explorers of contemporary slave labor. According to Mattos (2015), the textile industry directly benefits contemporary slave labor, especially because its production is short-term, and China is one of the main users of this type of labor, making it extremely competitive in this market.

Using this situation of vulnerability of the human being, the “fashion industry” uses slave-like labor as a way to lower its production costs. The textile industries, through outsourcing of their activities, end up contributing to the precariousconditions of working conditions, delegating their activities to workshops of formal or even homemade seams.

This slave labor exploitation system, used by textile industries, is known as sweating system, being the most found form of contemporary slavery in the urban environment around the world. The English term, also known as “sweat system” (our translation), refers to workplaces performed in unusual places that end up confusing with residences and offer extreme working conditions and miserable wages (Cristova e Goldschmidt, 2012).

It is noteworthy that the main subjects led by these systems are foreigners, usually from more underdeveloped countries, such as some Asian and Latin American countries. For, due to the condition of miserability that they are in their home countries, they end up attracted by false job offers. Thus, an environment is created by the capitalist market, in which companies seek outsourcing as a way of reducing costs and to increase competitiveness. The worker is subject ed to work in conditions analogous to the slave, out of necessity, giving room for the creation of small sewing workshops, which practice exploitation, through forced and degrading labor (Palo Neto, 2008).

The working conditions analogous to the slave in which the workers of the fashion industry in Brazil are found are part of contemporary urban slave labor, a little less common than the rural one, but it is likewise a major problem.

This network of slavery in the urban environment is directly linked to the immigration of foreigners, coming mainly from poorer countries in Latin America. Labor that is attracted to work in the factories of clothing. This fact does not exclude the internal trafficking of people themselves, who are directed from the interiors of Brazil, from small municipalities, to large metropolises (Mattos, 2015).

The growth of this type of crime occurred mainly, according to Santos (2015), due to the increase in the importance of the textile industry for the country’s domestic market in recent decades, due to the expansion of the middle class and access of the lower classes to credit lines, intensely stimulating consumption (Palo Neto, 2008). In 2012, the country’s industry created 1.7 million formal jobs, of which 733,000,000 are concentrated in the garment industries (Campos, 2015).

Therefore, because Brazil has a textile industry relevant to its economy, added to the ease of cheap labor in Latin countries (neighbors) and the need to become more competitive in the face of external mercar, foreigners have become an easy prey for the implementation of the production system mentioned above, the sweating system.

The sweating system is a form of outsourcing that big brands find to lower their production costs while trying to exempt themselves from labor responsibilities.

This system has as characteristic, workplaces that are confused with residences, in which workers work under deplorable conditions, suffering oppression, receiving miserable wages, having exhaustive and precarious working hours.

This form of work, where there is no minimum of respect for labor laws, in which remuneration is only for production, is also known as “sweat system” (our translation). In Brazil, this type of work is more common among foreign workers (Cristova and Goldschmidt, 2012).

One of the most significant cases in recent years occurred in 2011, in the city of Americana, involving the “Zara” store, in the State of São Paulo, in which the Labor Prosecutor’s Office discovered 51 people (mostly Bolivians) working in conditions analogous to slavery in a clothing factory supplying the large brand in question. The workers were subjected to strenuous journeys of up to 14 hours a day, receiving twenty cents per piece produced (Cristova e Goldschmidt, 2012).

Another case of great repercussion was the involvement of the Pernambucanas network, which, even after being investigated in 2010 and 2011, did not want to sign a Conduct Adjustment Term with the Public Prosecutor’s Office, being sued for exploitation of labor (Cristova and Goldschmidt, 2012).

In Brazil, the fight against this type of practice occurs mainly by public agencies such as the Public Ministry of Labor, Federal Police, Federal and State Governments, and by international organizations, such as the OIT, which seek through supervision and punishment, to curb this type of inhuman practice that mainly affects Latin American foreigners, with a considerable majority coming from Bolivia , in the intention of escaping the terrible living conditions that are there.

According to Mattos (2015), the majority of people who are subjected to degrading working conditions in the textile industry in Brazil are Bolivian, who leave their country due to the precarious socioeconomic situation, corruption and government system, since the country has some of the worst social indicators in South America.

Seeking only profit, companies hire Bolivian immigrants and pay them according to production, subjecting them to low wages, exposing them to exhausting and degrading journeys, which reach up to 16 hours a day. They also suffer from forced labor, in the face of the limitation of their freedom, through debts that are born of irregular collections, or because they are being documented illegally.

Thus, the bolivian workforce meets the momentary need of the textile sector, since they are disposable, temporary and isolated workers, without social protection, who adequately fill the void of cheap services, renegade by Brazilians.

Brazil has for decades adopted the fight against this type of practice through the union of governments and non-governmental organizations. And it was through supervision that many cases of Bolivians in conditions analogous to the slave have been discovered and fought. One of the most surprising cases occurred in 2011, in the city of Americana, in the interior of São Paulo, in which the Public Ministry of labor discovered 51 people, of these 46 Bolivians, working in conditions analogous to slavery, in a degrading and inhuman way in a workshop, which in turn had been hired by a large retail store, “Zara”. Workers worked an average of 14 hours a day and received R$ 0.20 (twenty cents) per piece of clothing produced (Cristova and Goldschmidt, 2012).

Another case that gained a lot of national repercussion was involving the large retail store “Marisa”, which received 48 infraction notices for keeping 16 Bolivians in a situation of contemporary slavery, in the city of São Paulo. The workers were submitted to 14-hour daily hours, receiving only R$ 247.00 (two hundred and forty-seven reais). In addition, documents were found on the site that proved the trafficking of immigrants across the border (Campos, 2015).

Not running away from most of the other cases that occur in Brazil, the workers found were mostly Bolivian immigrants, who were enticed through promises of employment and better living conditions. However, upon arriving in Brazil, the reality was different. They were trapped in a debt system, mainly involving food, transportation and documentation (Mattos, 2015).

CONCLUSIONS

Due to his new clothing, contemporary slave labor became invisible for some time, but with the efforts of international organizations and several countries, he has now been recognized and conceptualized, and his combat is possible.

The factors that make it possible to commit this crime, even if in today, it is basically related to a tripod: impunity, poverty and profit.

The situation of misery of the neediest population forces them to undergo types of work in subhuman conditions. In the case of the textile industry, these workers are coerced by sewing workshops, which in turn provide outsourced services to large retail stores, characterizing the sweating system of production.

The competitiveness of the market, seeking profitability at any price, causes the textile sector to subject workers to sixteen hours daily, in unhealthy places and deprived of their freedom.

These textile workers are mainly immigrants from neighboring, underdeveloped countries from Latin America. The main country supplying the workforce is Bolivia, which has a large population in poverty, which seeks better living conditions in the neighboring country.

Brazil was one of the first countries in the world to recognize this type of work, and that jointly with the International Labor Organization (ILO) and oysternon-governmental entities seek to combat such criminal practice on their territory.

Therefore, slave labor is still a reality in Brazil and in the world, finding conditions to proliferate in the Brazilian textile sector.

REFERENCES

ARAÚJO JÚNIOR, F. M. Dano moral decorrente do trabalho em condição análoga à de escravo: âmbito individual e coletivo. Revista do Tribunal Superior do Trabalho, v. 72, n. 3, p. 87-104, 2006.

AUDI, P. A escravidão não abolida. In: VELLOSO, G. e FAVA, M. N. (Ed.). Trabalho Escravo Contemporâneo: o desafio de superar a negação. São Paulo SP: LTr, 2006.

BALES, K. Gente descartável: A Nova Escravatura na Economia Mundial. Lisboa: Editorial Caminho, 2001.

BRASIL. Lei n. 2.848, de 07 de setembro de 1940. Institui o Código Penal., Brasília DF, 1940. Disponível em: < http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto-lei/Del2848compilado.htm >. Acesso em: 02 de jun. 2018.

______. Código penal – Decreto-lei no 2.848/1940. TÉCNICAS, C. D. E. Brasília DF: Senado Federal: 138 p. p. 2017.

BRITO FILHO, J. C. M. D. Trabalho com redução do homem à condição análoga de escravo e dignidade da pessoa humana. Genesis: revista de direito do trabalho, v. 23, n. 137, p. 673–682, 2004.

CAMPOS, L. R. J. D. O trabalho análogo à condição de escravo no setor têxtil brasileiro. 2015. 41p. (Especialização). Universidade Tuiuti do Paraná, Curitiba PR.

COSTA, C. Para que serve a ‘lista suja’ do trabalho escravo? , 2015. Disponível em: < https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/noticias/2015/04/150402_trabalho_escravo_entenda_cc >. Acesso em: 17 jun. 2018.

CRISTOVA, K. G.; GOLDSCHMIDT, R. O trabalho escravo contemporâneo no Brasil. Anais III Simpósio Internacional de Direito: dimensões materiais e eficaciais dos direitos fundamentais. IIISID. Chapecó SC: 24 p. 2012.

DAMIÃO, D. R. R. Situações análogas ao trabalho escravo: reflexos na ordem econômica e nos direitos fundamentais. São Paulo SP: Letras Jurídicas, 2014.

DOU. LEI Nº 14.946, DE 28 DE JANEIRO DE 2013. São Paulo SP, 2013. Disponível em: < http://dobuscadireta.imprensaoficial.com.br/default.aspx?DataPublicacao=20130129&Caderno=DOE-I&NumeroPagina=1 >. Acesso em: 28 maio 2018.

FAUSTO, B. História do Brasil São Paulo SP: Editora da Universidade de São Paulo, 2004.

GERHARDT, T. E.; SILVEIRA, D. T. Métodos de pesquisa. Porto Alegre RS: Editora da UFRGS, 2009. 120p.

GORENDER, J. O escravismo colonial. São Paulo SP: Ática, 1985.

GRECO, R. Curso de Direito Penal: parte especial. Niterói RJ: Impetus, 2008.

LIMA, T. C. S. D.; MIOTO, R. C. T. Procedimentos metodológicos na construção do conhecimento científico: a pesquisa bibliográfica. Rev. Katál., v. 10, p. 37-45, 2007.

MARTINEZ, L. Curso de Direito do Trabalho: relações individuais, sindicais e coletivas do trabalho. São Paulo SP: Saraiva, 2015.

MARTINS, S. P. Direito do Trabalho. São Paulo SP: Atlas, 2011.

MATTOS, C. N. S. D. Análise contemporânea do trabalho análogo ao escravo na indústria têxtil. 2015. 56p. (Graduação). Centro Universitário Eurípides de Marília – UNIVEM, Marília SP.

MIRANDA, C. C.; OLIVEIRA, L. J. D. Trabalho análogo ao de escravo no brasil: necessidade de efetivação das políticas públicas de valorização do trabalho humano. Revista de Direito Público, v. 5, n. 3, p. 150-170, 2010.

MONTEIRO, L. A. Políticas públicas para erradicação do trabalho escravo contemporâneo no Brasil: Um estudo sobre a dinâmica das relações entre os atores governamentais e não-governamentais. 2011. 184p. (Mestrado). Fundação Getulio Vargas, Rio de Janeiro RJ.

MONTENEGRO, A. T. Reinventando a liberdade: a abolição da escravatura no Brasil. São Paulo SP: Atual, 1997.

MOTA, M. B.; RAMOS, B. P. História das Cavernas ao Terceiro Milênio. São Paulo Sp: Moderna, 1999.

MTE. Quadro geral de operações de fiscalização para erradicação do trabalho escravo – SIT/SRTE – 1995/2010. Brasília DF, 2018. Disponível em: < http://www.mte.gov.br/fisca_trab/quadro_resumo_1995_2010.pdf >. Acesso em: 18 jun. 2018.

NASCIMENTO, A. M. Curso de Direito do Trabalho. São Paulo SP: Saraiva, 2010.

OLIVEIRA, J. S. D. O trabalho escravo conteporâneo no Brasil. 2011. 50p. (Especialização). Universidade Anhanguera-Uniderp, Fortaleza CE.

PALO NETO, V. Conceito jurídico e combate ao trabalho escravo contemporâneo. São Paulo SP: LTr, 2008. 128p.

PINSKY, J. Escravidão no Brasil. São Paulo SP: Contexto, 1992.

PRADO, A. A. Trabalho escravo hoje. Brasília DF, 2005. Disponível em: < https://www.anamatra.org.br/artigos/863-trabalho-escravo-hoje-09477223427479363 >. Acesso em: 15 jun. 2018.

PRONER, A. L. Neoescravismo: análise Jurídica das Relações de Trabalho. Curitiba PR: Juruá, 2010.

RODRIGUEZ, P. A. D. S. Princípios Constitucionais aplicado ao Direito do Trabalho: Colisão de Princípios nos casos concretos. 2015. 49p. (Especialização). Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre RS.

SARAIVA, R. Direito do Trabalho. São Paulo SP: Método, 2012.

SILVA, J. B. D. Trabalho escravo rural no brasil contemporâneo – uma ofensa à dignidade humana. 2009. 45p. (Especialização). Instituto Brasiliense de Direito Público, Brasília DF.

SILVA, M. R. D. Trabalho análogo ao de escravo rural no Brasil do século XXI: novos contornos de um antigo problema. 2010. 280p. (Mestrado). Universidade Federal de Goiás, Goiânia GO.

SIMÓN, S. L.; MELO, L. A. C. D. Direitos humanos fundamentais e trabalho escravo no Brasil. São Paulo SP: LTr, 2007.

SOARES, S. F. Notas estatisticas sobre a producção agricola e carestia dos generos alimenticios no Imperio do Brazil. Rio de Janeiro RJ, 1860. Disponível em: < http://www2.senado.leg.br/bdsf/handle/id/221678 >. Acesso em: 20 jun. 2018.

[1] Lawyer, Bachelor of Law (CEAP – Center for Higher Education of Amapá), Specialist in labor law and labor process by the educational institution Damásio.

[2] Lawyer, Bachelor of Law (CEAP – Center for Higher Education of Amapá), specialist in Civil Procedural Law by the institution Damásio Educacional.

[3] Theologian, PhD in Clinical Psychoanalysis. He has been working for 15 years with Scientific Methodology (Research Method) in the Guidance of Scientific Production of Master and Doctoral Students. Specialist in Market Research and Research focused on health.

[4] Biomedical, PhD in Tropical Diseases, Professor and researcher of the Medical Course of Macapá Campus, Federal University of Amapá (UNIFAP), Pro-Rector of Research and Graduate Studies (PROPESPG) of the Federal University of Amapá (UNIFAP).

[5] Biologist, PhD in Tropical Diseases, Professor and researcher of the Physical Education Course, Federal University of Pará (UFPA).

[6] Biologist, PhD in Theory and Behavior Research, Professor and researcher of the Chemistry Degree Course of the Institute of Basic, Technical and Technological Education of Amapá (IFAP) and the Graduate Program in Professional and Technological Education (PROFEPT IFAP).

Submitted: May, 2021.

Approved: May, 2021.