ORIGINAL ARTICLE

GERONE, Lucas Guilherme Tetzlaff de [1], JUNIOR, Acyr de Gerone [2]

GERONE, Lucas Guilherme Tetzlaff de. JUNIOR, Acyr de Gerone. A study on spirituality in health care from a theological perspective. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 05, Ed. 09, Vol. 01, pp. 137-156. September 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access Link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/science-of-religion/theological-perspective

SUMMARY

Studies on the relationship between spirituality and health are recurrent themes in academic research. However, little is said about the importance of spirituality in the practice of health care based on a biblical-theological reflection. This is the objective of this article, which discusses: health care from a theological perspective; a biblical reflection on health; christ as a model of health care; spirituality in the care of health professionals; the pastoralist-chaplain and the care of the sick. Methodologically, this article establishes itself as a case study. The results show that: a) there is a relationship between the etymological views of spirituality and health; b) there is an inseparable relationship between religious life and health in the stories narrated in the Holy Bible, which contemplate the notion of health, the practice of care and health recommendation and prevention; c) there is a finding that religious communities are places of holistic care because they contemplate the spiritual and emotional health of the individual, while promoting a community context of social health; d) there is a significant contribution of spirituality in the daily life of health professionals, providing them with greater support to deal with personal and patient suffering; e) there is an understanding of health professionals that spirituality in the practice of health care is a function of the chaplain/pastoralist. It is necessary to conduct new interacademic research on the theme in question, especially in the area of theology, given its significant contribution to humanization in health and integral care of the human being.

Keywords: Care, spirituality, health, health professionals, pastoralist.

INTRODUCTION

In the relationship between spirituality and health under the foundations of Christian theology, it is reflected on the existence and full salvation of the human being. This is the objective of this study that will use theoretical references of Christian theology from the perspective of health and, references of the health area from the perspective of holistic care, which includes the spiritual dimension.

This study is structured on the theological premise that Christ had the practice of caring for the sick from a look that contemplated holistic existence, in which the human being is a biological, psychological, social and spiritual being. The Greek term sozo, translated by salvation in the New Testament due to semantic breadth, is concomitant with the biopsychosocial dimension. Thus, salvation contemplates the notion of health: physical and biological, social, mental/psychological and spiritual well-being (SCLIAR, 2007).

It is also considered that theological reflection contributes to a better understanding of the practice of holistic health care. For the theologian Álverez (2013), health is a polyhedical and multidimensional reality, not reductable from the medical and biological scientific view[3]. Therefore, even though medical science provides knowledge of the cause of the disease, it is limited when it objectives and underestimates body and human reality (ÁLVEREZ, 2013). In multidimensional valorization in health, spirituality – a theological dimension – is a fundamental part of holistic care. It is spirituality that differentiates the human being from other living beings, with the ability to be free and to resist the adversities of life by offering a condition of resilience in the midst of pain, suffering of patients, family members and health professionals (TAVARES, 2013).

Theology, as a science of faith and of what is spiritual, dialogues with health. In biblical theology, the Old Testament and the New Testament, health care practices are found. The book of Leviticus, for example, presents the care of the sick, the social care, and the action of the priest from a clinical-medical perspective (Lv 14.31; 15.25-30). In the Gospel of Jesus, as Luke wrote, Christ “the doctor” (Lk 5:12-16) develops a model of care where salvation and health go together in the saving plan for the human being. According to Karl Barth, every conception of salvation in the Old and New Testaments has been related to health, since creation, food, work, rest, sickness, death, and the promise of salvation that Israel had had been fulfilled in Christ (ROCCHETA, 1993).

In systematic theology, based on its ecclesiological bias in its relationship with the health context, the religious community is characterized as a place of holistic care. The coexistence between members stimulates a healthy environment in mutual care. Therapeutic communities, nursing homes and orphanages are places of social health care. Pastoral counseling groups promote psychospiritual care (TILLICH, 2005). Already under a missiological presupposition, the missional action of the pastoralist-chaplain in the spiritual, psychological and social care of the sick, the families of the sick and the health professionals stands out. Finally, mystical theolo[4]gy integrates health care through the presence, gestures, words, prayers, sacred texts, music, silence, providing strengthening, counseling and comfort in times of anguish and uncertainty with the sick, the families of the sick and health teams.

1. PERSPECTIVES ON SPIRITUALITY AND HEALTH FROM A CHRISTIAN THEOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVE

Spirituality refers to the state of the nature of the spirit, something inherent to all human beings. It is the exercise of what is spiritual. According to the theologian Waldir Souza (2013, p. 97), spirituality is “a human condition from which one does not escape”, an existential dimension cultivated in the depths of the being that drives in its knowledge and in its vital pursuits. According to the doctor Puchalski (2006), spirituality can be understood as one:

each person’s inherent search for the meaning and ultimate purpose of life. This meaning can be found in religion, but it can often be broader than that, including the relationship with a divine figure or with transcendence, relationships with others (pp. 14-15).

Spirituality is a dimension that develops from the experiences that unfolds in behavior (religious or not). From a perspective of Christian[5] theology, the notion of spirituality is not understood as something material, but it is a transcendent dimension, originated in God himself who, through his Spirit, emanades in all life: “The Spirit of God created me, and the breath of the Almighty gave me life” (Job 33:4)[6]. The Evangelist John says that God is spirit, and it is important that his worshippers worship him in spirit and in truth” (John 4:23-24). It is understood that worshippers are those who recognize the Spirit of God as the vital and real essence in what is lived and done. Therefore, it is the Spirit of God that constitutes the meaning of life. At the same time, Jesus says that his words “are spirit and are life” (Job 6:63). Christ himself is the Word, “the Word”, in which the spirit of life emanates and the experience of “all things of what has been done and done” (Job 1:1-5).

In this way, the Word is the culmination of Christian[7] spirituality, for it is an action of God who, through Christ[8] , proves the essence, meaning and purpose of life for the created being (John 1:1-[9]4). It is not enough to exist, to feel, to have essence of life, to have spiritual experience, to have a connection with God. Then comes the religiosity that is nothing more than an extension of what is part of religion, understood here from its Latin etymology, religare, which means “reconnection”, that is, a connection between the human being with God (DERRIDA, 2000).

Etymologically, “health” has its origin in Latin salutis, or salus, which means to save, heal, rid or preserve life (LUZ, 2009). In this sense, the meaning of health designates a broad notion that should also contemplate a soteriological reflection[10]. The most used notion of health in academic research is from the WHO (World Health Organization), which reinforces that health is a notion of complete physical, mental, spiritual and social well-being. For Scliar, this notion seeks to express “a full life” (2007, p. 37).

In the theological notion, a full life proves the liberating and saving gift of Jesus, who brought life in abundance (DURÃES E SOUZA, 2011). Abundance is having a sense of living even in the midst of the human condition, such as illness. This becomes liberating in that it does not limit the concept of a healthy life only in having (or not) an illness. Rather, however, it is a life that transcends the human condition of illness, with a focus on a life of salvation.

1.2 BIBLICAL UNDERSTANDINGS ABOUT HEALTH IN A PERSPECTIVE OF CARE

Bible reading performed with patients is an important aspect of health care practice, since “many patients report liking to read religious materials while in hospital” (GERONE, 2015, p.86). Similarly, for health professionals, “giving counsel and comforting family members becomes easier with the wisdom and comforting words we find in the Bible” (p. 86).

The Bible provides special attention to caring for the sick. In the Hebrew tradition there is no specific word for the term health. To express something closer to the notion of health, the term shalom was used, from the Semitic root slm, which gives the idea of “peace”, “being unharmed”, “satisfied”. That is, the term shalomé broad in its meaning[11], however, when used in the concept of health, shalom is the designation that applies in the understanding of living under a total health condition, a full well-being, as for example, appears in biblical narratives in the book of Genesis, chapter 29.6[12] and chapter 43.27-28[13].

With more than two hundred quotations in the Old Testament, the term shalom also refers to the relationship arising from god’s covenant with human beings. As such, the absence of shalomcharacterized the distance between the human being and God as a consequence of the practice of sin. Therefore, living in a condition of shalom also meant living a condition in which the ideal of not sin was sought (ÁLVEREZ, 2013).

In the Old Testament, the Hebrew people believed that the disease was caused by sin and health in obeying God (Gen 12:17; Pv 23:29-32). When the people of Israel were being constituted on the way out of Egypt, God said, “I am the Lord, and it is health that I bring you” (R15:26). In the book of Ecclesiastes, in which there are meditations on the vulnerability of human life, a passage states that “from God comes all healing” (Ecto 38:1-9). The Hebrew belief that the disease comes from sin and that God provides health and healing has implied a diligent practice in health care among the Hebrew people. An example of this reality is the fact that the priest, a central figure in Old Testament theology, in addition to practicing his religious functions had to be equally on some health issues.

Similarly to the practice of a doctor, in cases of skin diseases, for example, it was up to the priest: “to examine the affected part of the skin, and if in that part the hair has become white and the place seems deeper than the skin is a sign of leprosy”. There was an examination and a subsequent diagnosis which, if the disease was found, resulted in a religious practice of purification, that is, a form of health care as observed in the Biblical account: “And thus the priest will make propitiation before the Lord in favor of him who is being purified” (Lev 13:3,14.31).

If the cure was not achieved by propitiation, it was up to the priest to exclude the leper from religious duties and social life. This exclusion, in addition to religious motives (a possible sin of the sick), was also characterized as a method of prevention and control of epidemics among the population. Due to the medical limitation of the time, the precariousness of medications and the lack of appropriate treatments, a contagious disease, such as leprosy, could pass from one person to another during the act of talking, sneezing, coughing or kissing, that is, it was easy to transmit (SCLIAR, 2007). Therefore, the exclusion of the leper-sick from social and religious life was a way of taking care of the health of the whole community. As can be seen, it is something very similar with current hospital care, in which patients with highly communicable diseases are hospitalized in isolation in closed places and away from living and contact with other people, in order to avoid an epidemic of the disease.

In the New Testament, in Jesus, the High Priest (Hebrews 2.17; 4.14) there is a new perspective on health care. In a passage described in the Gospel of Matthew, in a context of dialogue, the disciples asked Jesus, “When we saw you sick, or in prison, and went to visit you? And the King will answer unto them, “I say unto you, when you have done it to one of these brethren of mine, even the smallest of mine, you have done it to me” (Mt 25:39-40). For Jesus, caring for a sick man was the same as taking care of himself. Jesus is the essence and embodiment of health. It is not something he has brought, but it is the expression of his own identity. He is the one anointed by the Spirit, the therapist, the deliverer, and the Savior of those who are sick and oppressed (Lk 4:18).

Unlike the priest of the Old Testament, for whom the disease was caused by sin and which resulted in social exclusion, for Jesus Christ, the message of salvation contemplated a rescue of the spirit, body, and soul. According to Álverez (2013), Christ establishes a process of total transformation that reaches even the deepest secludes of the soul and heart. Nothing is deleted and nothing is less important. Everything points to salvation: life and death, sickness and healing, the body and what happens in it. Christ offers human beings, always in need of a holistic healing, a health that restores the dignity of the condition and human experience.

This notion of holistic care becomes part of the ministry of the disciples and apostles, such as the Apostle John who, in writing to the priest Gaius says: “Beloved, I desire that you do well in all things, and that you have health, as well as your soul goes” (3 Jn 1:2). For the Apostle John, health and soul are integrated into Gaius’ full human existence. Even in the midst of possible illness one can be healthy and do well in all things of life when the soul is well. As Álverez (2013, p. 272) states, “in the disease not everything becomes necessarily pathological, it can be even therapeutic and healthy, or be lived in a holy and healthy way; it is possible to find grace in disgrace.”

1.3 CHRIST AS A MODEL OF CARE FOR HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

As has already been seen, the New Testament presents the practice of health care performed by Christ. Luke the evangelist who was a doctor, has a greater sensitivity in reporting the events related to health issues in the ministry of Christ. The Lucan text recounts health care as something deeply characteristic of Christ: “[…] the whole multitude sought to touch him, because he came out of it virtue, and healed everyone” (Lk 6:19).

Jewish laws strongly prohibited physical contact with people affected by certain diseases. For example, a woman who suffered a hemorrhage should not touch anyone (Lv 15.25-30). However, Jesus did not avoid being touched by a bleeding woman. As Jesus was touched, he manifested virtues of humanized care, love, dignity, and then healing (Matthew 9:20-22; Mark 5.25-34; Luke 8.43-48). Loving one’s neighbor is an act of saving care (1 John 3:17-18) that restores life (1 Peter 4:8).

Just as Christ did to the sick, health professionals recognize the importance of touch in care. According to health care method developed by doctors Fritz Talbote Winnicott, touch creates a relationship between humans and has the ability to transmit love. These are fundamental issues that value and signify human dignity (MONTAGER, 1988).

In addition to physical healing, in the practice of health care, it is necessary to offer virtues of hope, dignity and love. Healing alone does not respond to the totality of human health. According to Laín (1984, p. 187), “no one enjoys complete health if they cannot answer the question: health for what? We don’t live to be healthy, but we are healthy to live and act.” This reality demands hope, faith, dignity and love (1 Cor 13:13). Hope and faith result in meaning and resilience for life (Jn 16:33).

Like Christ, for health professionals virtues are indispensable conditions for health care. Faced with the inability to cure a disease through traditional medical treatment, one can exercise humanized care to the sick, providing hope and love. This is the perception found in a case study that researched the theme among health professionals. They claim that:

a) “Talking about God and his love and mercy comforts and gives hope to our patients. They become more confident about the treatment and often the response to treatment is surprising!” b) “In the experience I have had so far I have been able to realize that confidence in a higher being and religiosity gives an impulse and hope for the patient to seek strength to perform treatment and seek healing or even develop a new reason to want to live.” c) “In the experience I have had so far I have realized that trust in a being superior and religiosity gives an impulse and hope for the patient to seek strength to perform treatment and seek healing or even develops a new reason to want to live.” d) “I try to talk about their belief and their faith and always try to stimulate this practice of faith to improve the treatment of the patient and companions. Having healing faith is the most important thing for us to act with the healing of medicine” (GERONE, 2015, pp.88).

Based on these reports of health professionals in the practice of care for the sick, it is observed that spirituality can provide the cure of the psique[14], that is, the psychoemotional health of the patient. In the practice of christ’s care to the afflicted in heart (psychoemotional issues), the state of the “spirit” was the condition for the healing process (Lk 4:18). The health area recognizes the psique in the healing process. Positive thoughts, peace, hope and faith collaborate significantly in medical treatment and in discovering a sense of living. After all, sometimes, in the midst of illness, a feeling of oppression and depreciation of life arises that negatively affects the psychoemotional state of the sick. Therefore, before treating the clinical cause of the disease it is necessary to treat the essence, that is, the psique . And to heal the spirit, one must transcend[15]. For doctor Vitor Frankl:

By virtue of the transcendence of human existence, man is a being in search of meaning. He is dominated by the will of meaning. Today, however, the will of meaning is frustrated. More and more patients return to us psychiatrists complaining of feelings of meaninglessness and emptiness (FRANKL, 1989, p. 82).

According to Gerone (2015) health professionals who are Christians[16] understand spirituality as a dimension of transcendence that manifests itself in the divine or sacred presence in personal and professional life; in the existence of a higher being, such as a Spirit, for example; in the experience of the supernatural and in faith in Jesus. According to Augustine (2000), Jesus Christ is the immanent embodiment of the transcendent God. Transcendence in Jesus is revealed in spirituality, purpose, and sense of life so that “any who see the Son and believe in him may have eternal life (Jn 6:39), for “I have come that they may have life, and have it abundantly” (Jn 10:10).

1.4 METHODS OF INTEGRATING SPIRITUALITY INTO THE PRACTICE OF HEALTH CARE

There is no unanimity on a specific method for integrating spirituality into health care. However, there are some procedures acceptable by most health professionals, patients and family members that can contribute in this sense. For example, a brief spiritual history of the patient may be raised in the standard collection of socio-bio-demographic data. It is clear that, however, it is necessary to have the proper permission of those involved after an explanation of procedures. If such a procedure is authorized, according to Koenig, the patient may be asked if:

1. Do your religious/spiritual beliefs offer comfort or are they a source of stress?

2. Do you have spiritual beliefs that can influence your medical decisions? 3. Are you a member of a spiritual community and does it support you? 4. Do you have any other spiritual needs that would like to be met by someone? (KOENIG, 2012, p.161)

Does the American College of Physicians, a renowned medical organization that seeks to expand scientific knowledge and clinical experience on diagnosis, treatment and patient care, suggest that health professionals ask about the following aspects, so that religiosity/spirituality can be integrated (or not into care: (1) Is faith (religion, spirituality) fundamental to you in this disease? (2) Has faith (religion, spirituality) ever been important at other times in your life? (3) Do you have anyone to discuss religious issues? (4) Would you like to explore religious issues with someone else? (PERES, 2007).

It is emphasized that these methods were developed within the health field, that is, despite addressing aspects related to religiosity and spirituality, it is not a religious action. On the contrary, they are methods that enable health professionals to integrate spirituality into their care practice without losing ethics and professionalism. Therefore, spiritual history will serve to show patients that if there is any spiritual need it can be discussed and met. It will be up to health professionals to write in the medical records the observations about the needs scored. As an example, record whether patients would like to receive prayer, be referred to the chaplain/pastoralist, or would like to have the presence of a religious leader or another subject of the religious community.

2. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE RELIGIOUS COMMUNITY AND HEALTH PROFESSIONALS IN THE PRACTICE OF CARE

In the practice of spiritual and religious care offered to patients, it is possible for health professionals to establish a relationship with the religious community of the patient. Health care practices developed through the relationship between the religious community and health professionals occur through the use of liturgical acts and symbols and religious practices of prayer, the imposition of hands, blessing, absolution, the Eucharist and oil anoint. These manifestations are fundamental in the life of the faithful, after all they mark in a special way the situations of illness and health, birth and death, among other significant moments (GAEDE, 2007).

Among the symbolic practices mentioned that are part of health care, we have, for example, the imposition of hands that can be better understood as a Complementary Integrative Practice in Health (PIC’S). According to the Ministry of Health, the imposition of hands close to the body, transfers positive energy to the patient, promotes well-being, decreases stress, anxiety, depression and hypertension[17]. Therefore, these symbolic practices, which may also be religious, have no restricted use within the religious community. They are also part of the practice of health care. For doctor Koenig (2012), for example, the patient may ask health professionals to do the hand-enforcement together with a meditation or prayer.

The practice of collective prayer carried out by a community is found from Genesis to Revelation and portrays the deepest longings of all human existence. The practice of prayer emphasizes the sacred, reiterates gratitude and praise, presents the supplications and petitions. Therefore, in dualistic contexts between sadness and joy, sickness and health, prayer is the means by which hope is rescued in the midst of a difficult situation (e.g.: Psalm 121.1-[18]2). In this sense, “prayer was pointed out as one of the coping methods most used by patients in health-disease processes” (ESPERANDIO, 2014a apud ESPERANDIO, 2014b, p.815). The positive experiences resulting from the practice of prayer in health-disease contexts “point to decreased anxiety, improvement in the ability to function, search for a more assertive behavior and spiritual support for a life with more meaning and purpose” (ESPERANDIO; LADD, 2013, p. 644).

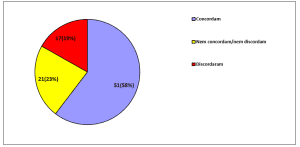

As Gerone (2015) points out, 94% of health professionals understand that patient religiosity is expressed through the practice of prayer, meditation and regular frequency in a religious community. For health professionals, the practice of prayer is a significant way to integrate spirituality and health:

a) “[…] I ask patients, no matter what religion, to always be praying and asking God to be in charge of their lives. I work with cancer patients, so I speak of God because they are oversensitive and often frightened by the diagnosis.” b) “During visits often, I usually say my prayers so that I can attend to patients/family members in their entirety.” (GERONE, 2015, p. 94).

The practice of prayer is not limited to the religious rite, but also manifests a state of mind that seeks to elevate life and mind above the disease and allows holistic care to patients regardless of the condition of physical healing. Prayer results in later acts, just as counseling, providing comfort, tenderness, solidarity and empathy, manifests in this community and fraternal experience among people. It is about union among members, as is the case, for example, in a Christian community known as the “body of Christ[19]”. The union between the members allows special attention to the sick (BRESSARI, 1999), in which if a member suffers, everyone suffers from it and if one of them is honored, all are honored with it (1 Cor 12:25).

One member’s motivation to support the other is not limited to the rigour of a social contract, but is anchored in the Principles of the New Testament of loving others and caring for those who suffer. This action usually happens on a social and therapeutic level through pastoral/ministries: women’s group, men’s group, group of children or the older. It is a means by which the religious community cares for, promotes, defends and celebrates life, human dignity, mental, spiritual and biological health (GAEDE, 2007).

The care practiced through the religious community also covers the scope of social health. According to Koenig (2012), social and economic crises at global levels have had an effect and reflected an increase in health plan values, causing a crisis in the public health system that has resulted in the scarcity of adequate hospitals for medical care in emerging countries. In this scenario, the religious community plays an important role for health promotion and care, acting as a social agent of transformation in the popular context in a very significant way. There are religious communities that create, support or maintain therapeutic communities, nursing homes, orphanages and hospitals, develop pastoral psychological support groups, and give lectures on disease prevention and health incentives for members and the local community.

Given the Brazilian context, whose public health is still so deficient, it is expected that the health care promoted by the religious community will grow and become even more effective in its action. That’s the American reality, for example. The religious communities themselves have their health professionals, such as doctors and nurses, who serve members and the population in general. Once the proper proportions and limitations are kept, religious communities can be an extension of hospitals, just as there is the extension of the religious community in hospitals through chaplaincies, prayer and meditation spaces and the performance of the chaplain/pastoralist (KOENIG, 2012).

3. THE PERFORMANCE OF THE CHAPLAIN/PASTORALIST IN THE CONTEXT OF HEALTH CARE

Chaplaincy is one of the most important works within a vulnerable reality in which the human being is when he is suffering from an illness. Therefore, the Brazilian Constitution of 1988 (Art. 5th, VII and Art. 210, paragraph 1) provides for and emphasizes the importance of religious care in a place of medical treatment. Religious assistance performed through chaplaincy in hospitals “intends to offer spiritual, emotional and social support, based on the Word of God, to people who are in these places” (GERONE JUNIOR, 2016, p. 125). For Alexsandro Silva (2010), the hospital chaplaincy service creates something similar to the ecclesial[20] environment that enables missionary action and collaborates in the integral formation of the human being through the presence, gestures, words, prayers, reading of sacred texts, music, silence, strengthening, counseling and comfort in times of anguish and uncertainty with the sick , to the families of the sick and to health teams.

Throughout the history of health, the religious care provided by a chaplain was linked to medical care. As an example, we have the performance of chaplain/pastoralist Anton Boisen, who for years worked as chaplain alongside doctor Richard Cabot in the care of the mentally ill. Boisen pioneered the integration of religious field students within a psychiatric hospital focused on clinical pastoral training. Another example is Leslie Weatherhead, who in 1916 became chaplain of the Indian army and worked with doctors in the care of the sick (SILVA, 2007).

Currently, the role of chaplain/pastoralist is usually part of the medical team (ASSUNÇÃO, 2009). The performance of the chaplain/pastoralist as part of the medical team is based on the fact that, “after all technical possibilities have been exhausted and all possible from the clinical point of view, we will be faced with the moment of greatest vulnerability and greater need for the sick” (SILVA, 2010, p. 28). Therefore, for health professionals:

a) “The presence of a religious representative in the face of the disease brings many benefits and help in recovery” b) “I note that the chaplaincy service used in hospitals provides a lot of security for us health professionals, and brings tranquility, mental comfort to patients. It is part of the treatment provided to the patient” (GERONE, 2015, pp.94).

It is perceived that health professionals give importance to the care provided by the pastoralist/chaplain, in which the religious issue dialogues with medical science in the improvement of health care. Also, it is perceived that health professionals value religious care to patients, but most health professionals prefer to attribute the practice of this care specifically to the chaplain/pastoralist. Of course, religious care is the main responsibility of the chaplain/pastoralist. However, when health professionals are able to integrate spirituality and health in patient care, a harmony and a better understanding of the patient himself in relation to the disease is established, thus strengthening the way in which the patient will face the disease (ASSUNÇÃO, 2009).

3.1 THE CHAPLAIN/PASTORALIST AND THE CARE OF HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

The performance of the chaplain/pastoralist in the hospital context also occurs through the care of those who care. This action is increasingly necessary, as it seeks to support, support and advise health professionals in the face of daily dealings with suffering, disease and death of patients (PAIVA, 2004). It is necessary to remember that one of the greatest challenges of health professionals is in the fight for the preservation of life and in dealing with a negative prognosis that needs to be communicated, whether to the patient or even a death to family members. This is a difficult task in which a feeling of possible failure emerges because the professional has not achieved full success in the treatment employed.

This situation can lead the professional to a mirror, in which there is a projection of himself in the same situation (ALVES, 2011). This is why many health professionals are exhausted physically and emotionally on many occasions. In these situations, the care provided by the chaplain/pastoralist may awaken in the health professional a positive feeling so that he can live and live in a more integrated work environment, with comprehensive senses of greater knowledge and self-confidence (PAIVA, 2004).

According to a health professional’s specific account: “it is very important to always be in god’s presence to face any problem, whether health or others.” (GERONE, 2015). It is perceived the need to develop the spirituality of health professionals, especially in contexts where there is a need to deal with the fragility of the disease or death that is inherent to the human being. There is, therefore, a demand for spiritual/religious care that can be carried out by the chaplain/pastoralist individually or even as a group, by means of counseling, meditation and prayer. Such action can help health professionals feel grounded and based on their faith and in communion with God so that they can perform better at work. In fact, as they say, they need to “be well spiritually, yes, before taking care of sick people” (GERONE, 2015, p. 89), after all, “when I am strengthened in my walk with God, I feel a lot of difference in relationships, at work, in studies among other activities I do in my daily life” (GERONE, 2015, p. 89).

Finally, the chaplain/pastoralist can help health professionals develop a better practice of patient care in order to combat stress in the workplace and better deal with the feeling of loneliness and in making difficult decisions about therapeutic interventions. The communication of difficult news is an example of this reality. Therefore, this work can result in a necessary humanization of labor relations, in the construction of dialogues and in the sharing of difficulties in the face of suffering and death (TAVARES, 2013).

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Spirituality and health are related in a holistic view of the human being. For the World Health Organization (WHO), spirituality composes the notion of health, because religious and spiritual beliefs influence the context of health-disease, such as the practice of health care. It is in this context that theology dialogues with health. After all, in theology that focuses on the saving aspect, saving also contemplates a practice of care of life in its biopsychosocial and spiritual dimension (ROCCHETA, 1993).

In biblical theology, the Old and New Testaments present and reflect on religious life related to the context of health and the practice of care. Christ is the embodiment of health and the paradigm of care. In it, health transcends illness by communiting with the saving plan and a meaning for life, even if it is faced with the human condition of the disease. Christ is the Savior who cares for, heals, and restores the human being holistically. This is the culmination of the Word of God and is the essential theological basis of Christian spirituality. In this sense, a biblical reflection more specific to the theme, points out Christ as the embodiment of health and the paradigm of care. Through this, it is evident that health professionals can develop a holistic and humanized care practice. And in addition to physical healing, in the practice of health care, it is necessary to offer virtues of hope, dignity and love.

From an ecclesial perspective, the religious community can provide health care through coexistence among members, building a healthy environment of mutual care and social, psychoemotional and spiritual support. It is emphasized that, in the current Brazilian context of crises in all areas (COVID-19, for example), studies on the role of religious communities in the health context are increasingly needed, in order to enable the practice of a healthier spirituality, both in the physical body and in the soul and mind of people.

Spiritual and religious practices are usually free of charge. Therefore, they provide significant economic benefits in the health service. That’s why people engaged in religious or spiritual actions are usually physically healthier, after all have a more balanced lifestyle and use fewer health services. Thus, spiritual practice contributes to the reduction of more costly expenses, also reducing the possibility of hospital expenses, medications and examinations. Therefore, it emphasizes the importance that health care promoted by the religious community grows and becomes even more effective in its action.

As has been seen, the pastoralist-chaplain’s mission in spiritual, psychological and social care for the sick, the families of the sick and health professionals is very important. Considering that the pastoralist-chaplain can be part of the medical team, his practice of spiritual care must be in tune with the practice of medical care, with the objective of ensuring a health care that is holistic, that is, that considers the human being in its biopsychosocial and spiritual reality. As a method of integrating spirituality into health care, health professionals can through the spiritual history identify the religious and spiritual needs of the patient and refer him to the pastoralist-chaplain, who can also assist health professionals, because, in the face of the suffering and death of the patient, in stressful situations in the hospital environment, health professionals feel vulnerable psychoemotional and spiritual.

It is evident the need to recognize the importance of spiritual and medical issues in the reflection that challenges the practice of health care, that is, caring for the human being in his multiple needs, granting him dignity and health that contemplates him in all dimensions. The human being is not only a body or a mind, much less, a soul or only emotion. It is also not the sum of these parts. The human being is a holistic being. A theological reflection in dialogue with health goes in this direction, that is, it looks at the integrality of the person and seeks to meet all needs.

Finally, one cannot practice alienating, separatist or asstic theology. Likewise, one should not practice health care that underestimates the intrinsic need for every human being, that is, the search for meaning for life in its search for the transcendent. Within the theological context of health, it is important that the person finds a sense of living even in the midst of the human condition of the disease. Life in abundance in Jesus is a life that transcends the human condition of illness, that is, it represents not only a life with health, but a life of salvation.

REFERENCES

ÁLVAREZ, F. Teologia da saúde. São Paulo: Paulinas/Centro Universitário São Camilo, 2013.

ALVES, M. A espiritualidade e os profissionais da saúde em cuidados paliativos. Dissertação de Mestrado em Cuidados Paliativos. Lisboa: Faculdade de Medicina de Lisboa, 2011.

ARAÚJO, M. O cuidado espiritual: um modelo à luz da análise existencial e da relação de ajuda. Tese de Doutorado em Enfermagem. Fortaleza: Universidade Federal do Ceará, 2011.

ASSUNÇÃO, L. A relação entre ministros religiosos, médicos e pacientes no Instituto de Psiquiatria do Hospital das Clínicas de São Paulo. Anais do II Encontro Nacional do GT História das Religiões e das Religiosidades.Revista Brasileira de História das Religiões. v. 1, n. 3. Maringá, jan. de 2009

AZEVEDO, R. “O IBGE e a religião – Cristãos são 86,8% do Brasil; católicos caem para 64,6%; evangélicos já são 22,2%”. Disponível em: <http://veja.abril.com.br/blog/reinaldo/geral/o-ibge-e-a-religiao-%E2%80%93-cristaos-sao-868-do-brasil-catolicos-caem-para-646-evangelicos-ja-sao-222/>. Acesso em 29 de julho de 2014.

BRESSARI, E. Unção dos enfermos.Dicionário interdisciplinar da pastoral da saúde. São Paulo: Paulus/Centro Universitário São Camilo, 1999.

BRUSCO, A. “Capelania Hospitalar”. In VENDRAME, Calisto; PESSINI, Leocir (diretores da edição brasileira). Dicionário interdisciplinar da pastoral da saúde. São Paulo: Centro Universitário São Camilo e Ed. Paulus, 1999.

BÍBLIA SAGRADA. Bíblia de Jerusalém. São Paulo: Paulus, 2002.

BÍBLIA SAGRADA. Edição Revista e Corrigida. São Paulo: Sociedade Bíblica do Brasil, 1969.

DERRIDA, Jacques; VATTIMO, Gianni (orgs.). A religião: o seminário de Capri. São Paulo: Estação Liberdade, 2000.

ESPERANDIO, M. R. G. “Prayerand Health. A PortugueseLiteratureReview”. Rev. PistisPrax., Teol. Pastor., Curitiba, v. 6, n. 1, p. 51-66, jan./abr. 2014.

ESPERANDIO, M.; LADD, K. L. “Oração e saúde: questões para a Teologia e para a Psicologia da Religião”. Horizonte Revista de Estudos de Teologia e Ciências da Religião. v. 11, pp. 627-656, 2013.

ESPERANDIO, M. “Teologia e a pesquisa sobre espiritualidade e saúde: um estudo piloto entre profissionais da saúde e pastoralistas”. Horizonte Revista de Estudos de Teologia e Ciências da Religião. v. 12, n. 35, pp. 805-832, jul./set. 2014b

GAEDE, R. “Implicações para as relações de cuidado”. In: HOCH, Lothar Carlos; L. ROCCA, S. M. Sofrimento, resiliência e fé: implicações para as relações de cuidado. São Leopoldo: Sinodal/EST, 2007.

GERONE, Lucas Guilherme Teztlaff de. Um olhar sobre a Religiosidade/Espiritualidade na Prática do Cuidado entre profissionais de saúde e pastoralistas. Dissertação (Mestrado em Teologia) – Escola de Educação e Humanidades. Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Paraná. Curitiba, 2015. Disponível em: <http://www.biblioteca.pucpr.br/tede/tde_busca/arquivo.php?codArquivo= 3116>. [Acesso em 27 dez. 2019.]

GERONE JUNIOR, Acyr de. Retratos urbanos: os desafios da igreja na cidade. Rio de Janeiro: Pilares Editora, 2016

GEORGE WEIGEL. A verdade do catolicismo: resposta a dez temas controversos. Lisboa: Bertrand Editora, 2002.

KOENIG, H. Medicina, religião e saúde: o encontro da ciência e da espiritualidade. Porto Alegre: LMP, 2012.

LAÍN, Entralgo P. Antropologia médica. Barcelona: Salvat, 1984.

LEVIN, J. Deus, fé e saúde – explorando a conexão espiritualidade-cura. São Paulo: Cultrix, 2003.

LUZ, M. Origem etimológica do termo. Disponível em: <http://www.epsjv.fiocruz.br/dicionario/verbetes/sau.html>. Acesso em 1º out. de 2013.

MONTAGER, Ashley. Tocar: O significado humano da pele. São Paulo: Editora Summus, 1988.

PAIVA, J. Espiritualidade e qualidade de vida: Pesquisas em psicologia. Porto Alegre: EDIPUCRS, 2004.

PANZINI, R. Escala de copingreligioso-espiritual (escala cre). Dissertação de Mestrado em Psicologia. Porto Alegre: Univ. Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, 2004.

PERES, M. F. P. et al. “A importância da integração da espiritualidade e da religiosidade no manejo da dor e dos cuidados paliativos”. Revista Psiquiatra Clínica, São Paulo, v. 34, 2007. Disponível em <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0101-60832007000700011&lng=pt&nrm=iso>. Acesso em 16 de dezembro de 2013.

PUCHALSKI, C. M. “Espiritualidade e medicina: os currículos na educação médica”. JournalofEducation Câncer: O Jornal Oficial da Associação Americana para a Educaçãodo Câncer, 21 (1), pp. 14-18, 2006.

ROCCHETTA, C. “Salute e salvezzaneigestisacramentali”. Camillianum v. 7, pp. 9-27, 1993.

SCLIAR, M. “Histórico do conceito de saúde”. PHYSIS: Rev. Saúde Coletiva, Rio de Janeiro, n. 17, v. 1, pp. 29-41, 2007.

SILVA, A. A capelania hospitalar: uma contribuição na recuperação do enfermo oncológico. Dissertação de Mestrado em Teologia. São Leopoldo: Escola Superior de Teologia, 2010.

SILVA, M. Capelania Hospitalar como Práxis libertadora junto às pessoas com HIV/AIDS. 2007,123f. Dissertação (Mestrado em Ciências da Religião) Universidade Metodista de São Paulo. São Bernardo do Campo, 2007.

SOUZA, W. “A espiritualidade como fonte sistêmica na Bioética”. Rev. PistisPrax., Teol. Pastor., Curitiba, v. 5, n. 1, pp. 91-121, jan./jun. 2013.

STRONG, James. Léxico Hebraico, Aramaico e Grego. Barueri: Sociedade Bíblica do Brasil, 2005

TAVARES, C. “Espiritualidade e bioética: prevenção da ‘violência’ em instituições de saúde”. Rev. PistisPrax., Teol. Pastor., Curitiba, v. 5, n. 1, pp. 39-57, jan./jun. 2013.

TILLICH, P. Teologia sistemática. 5. ed. São Leopoldo: Sinodal, 2005.

TILLICH, P. The impactof pastoral psychologyontheologicalthought (1960). In: TILLICH, P. The meaning of health: essays in existentialism, psychoanalysis, andreligion. LEFEVRE, P. (Ed.). Chicago: Exploration Press, 1984. p. 144-150.

TRASFERETTI, J. “Teologia moral, bioética e cultura da morte: desafios para a Pastoral”. Rev. PistisPrax., Teol. Pastor., Curitiba, v. 5, n. 1, pp. 147-168, jan./jun. 2013.

APÊNDICE – REFERÊNCIAS DE NOTA DE RODAPÉ

3. A strictly physical view, which disregards the psychological, mental, social and spiritual dimensions (BRESSARI, 1999).

4. It deals with the Christian spiritual experience revealed in the sacramental rites, symbolisms, means of celebrations, songs, dances, dramatizations and gestures. CATÃO, F. Christian Spirituality. São Paulo: Paulinas, 2000, p.31

5. This is Christian theology because 84% of Brazilians are Christians, according to the 2010 IBGE (AZEVEDO, 2012)

6. God not only creates, but breathes, tastes and directs life. The breath here is understood as an action of God in providing essence, meaning and purpose of life for the created being.

7. “For the Word of God is alive and effective, and sharper than any double-edged sword; it penetrates to the point of dividing soul and spirit, joints and marrow, and judges the thoughts and intentions of the heart ”(Hebrews 14.12).

8. “For God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son, so that everyone who believes in him may not perish, but have eternal life” (John 3:16).

9. “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things were done through him, and without him, nothing that was done was done. Life was in him and life was the light of men ”

10. The area of theology that studies salvation in all its aspects (TILLICH, 2005).

11. Cf. STRONG, James. Strong’s Hebrew, Aramaic and Greek lexicon, no.h7965. The breadth of the word shalom is a challenge for Bible interpreters and scholars.

12. “I said more to them: Is he well (shalom)? And they said: Okay (shalom), and here is Rachel, her daughter, who comes with the sheep ”[Gen. 29.6]

13. “And he asked them how they were and said, ‘Is your father, the old man you spoke of, all right (shalom)? Still lives? 28 And they said, Well (shalom) is your servant, our father still lives. And they bowed their heads and bowed down ”[Gen 43: 26-27]

14. From the Greek psykhé, which portrays the human essence, the nature of spirit, thoughts, feelings, behaviors, conscience and personality (AULETE, 1980).

15. Derived from transcendence is understood as that which is beyond the thing itself; it is the existential essence and purpose; it is beyond physical and material; it is about what is metaphysical and spiritual.

16. In the results of a survey, 85% of health professionals are Christians (GERONE, 2015).

17. Ministry of Health. Department of Primary Care. Health Care Secretariat. Report of the 1st International Seminar on Integrative and Complementary Practices in Health – PNPIC. Brasília, DF: MS; 2009.

18. “I lift up my eyes to the mountains; where does the help come from? My help comes from the Lord, who made heaven and earth. ”

19. This expression is known from the apostolic archetype and Jesus’ mandate found in the Bible.

20. Hospital chaplaincy is also an ecclesial work organization that expresses the “religious service provided by the Christian community in the health institution. It consists of one or more priests, to whom can be added deacons, religious and lay people ”(BRUSCO, 1999, p. 140).

[1] Master in Theology from PUC/PR. He has a specialization in Organizational Behavior. He has a specialization in Neuropsychopedagogy, Philosophy and Sociology and Teaching of Higher Education. He has MBAs in Administration and Management with emphasis on spirituality and religiosity in companies. He has a degree in Commercial Management. He holds a Bachelor’s degree in Theology. He holds a Degree in Philosophy and a Degree in Pedagogy.

[2] PhD in Theology (PUC-Rio), Master in Education (UFPA), Specialist in Social Project Management in the Third Sector (FTBP) and in Religion Sciences (FAERPI). He holds an MBA in Business Management (FGV) and advertising, marketing and integrated communication (UNIESA). He holds a bachelor’s degree in Theology from the Bethany Theological Seminary of Curitiba, with validation by PUC-PR.

Submitted: August, 2020.

Approved: September, 2020.