REVIEW ARTICLE

GAMA, Uberto Afonso Albuquerque da [1], LIMA, Paulo Renato [2]

GAMA, Uberto Afonso Albuquerque da. LIMA, Paulo Renato. A brief analysis of Hinduism and its spiritual precepts for the contribution of human faith. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 04, Ed. 01, Vol. 08, p. 72-88 January 2019. ISSN: 2448-0959. Access Link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/science-of-religion/spiritual-precepts, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/science-of-religion/spiritual-precepts

ABSTRACT

Religion is the greatest need of human nature. Just as the body needs food to sustain itself and the mind knowledge to develop, the soul needs mystical-philosophical-religious experience for its perfection. In this brief analysis, Hinduism, one of the greatest ancestral religions, born in the foothills of the Himalayas, India, more than 10,000 years ago will be discussed, and a brief analysis will be made of these very rich philosophical-spiritual bases that have influenced and continue to influence profoundly. the faith of humanity.

Keywords: Hinduism, Precepts, Himalayas, India.

INTRODUCTION

The religious problem touches man at his ontological root. This is not a superficial phenomenon, but involves the whole person. The religious can be characterized as a zone of meaning for the person. In other words, religion has to do with the ultimate meaning of the person, history and the world. (ZILLES, 2004, p.6).

Religion is an association of human beings with God, and the ultimate aim of religion is truth. Various forms, rites and practices lead to the truth. Hinduism is a religion of practical experience. (SUBRAMUNIYASWAMI, 2000).

Hinduism, also known as Sanátana Dharma or Eternal Way, is an original living religion and the oldest on our planet, with more than one billion and one hundred million adherents. According to the Himalayan Academy (2018), today there are four main denominations: Shaivism, Shaktism, Vaishnavism and Smartism, and each with hundreds of lineages. These denominations represent a wide range of mystical and spiritual beliefs, practices and goals, but virtually all denominations agree on certain fundamental concepts. These concepts will be presented later.

Hinduism contains many beliefs, philosophies and viewpoints called Darshanas which are not always consistent with each other but all with great depth of thought. (DAS, 2012).

It is observed that Hinduism does not have a founder, that is, a founder or systematizer who has established rules, norms or some specific organization. According to Renou (1990) no one is seen as a precursor or codifier of this religion. It is incorrect to say that the Hindu is Indian. A person born in India is called an Indian, while someone who adheres to Hinduism is a Hindu. In Hinduism there were no reforms, no dogmas, no impositions. On the contrary, the contributions generated over the centuries overlapped without erasing the previous layers.

According to Renou (1990), it was said that Hinduism turned its back on Vedic beliefs. But it can equally be said that it is the continuation of the Vedas. Thus, it is understood that the sacrum and its foundation are contained in two great divisions: Shruti (divine inspiration) and Smriti (memory).

According to Shri Subramuniyaswami (2000), the sacred Vedas date from approximately 8,000 years ago, therefore, 6,000 years before Christ, long before the Christian Bible. The composition of four great sacred books is seen, namely: Rig Vêda, Yajur Vêda, Sama Vêda and Atharva Vêda. Each of these age-old books of wisdom has specific subchapters and subdivisions.

For over 2,000 years, Western Christian schools have sought to understand Hinduism, the faith of its followers, its veneration of hundreds of gods, and its surrender to Brahman, also called the Absolute, the supreme, invisible, omnipotent, omniscient, and omnipresent God. (SUBRAMUNIYASWAMI, 2000).

It is understood that Hinduism is a religion with immense complexity, but, at the same time, of an impressive simplicity and purity. Perhaps this is one of the reasons for so much support on the part of Westerners.

SYNOTIC DIVISION OF HINDUISM

According to Shri Subramuniyaswami (2000), the Vedas and Agamas are revealed by God, and show an extraordinary mystical and poetic depth of man’s knowledge.

Table 1. Synoptic Division of Hinduism

| HINDUISM | |||

| Authorized Sources | Holy Books | Final Chapters of the Holy Books | Important Upanishads |

| SHRUTI (That which is heard, or divine inspiration) |

VÊDAS: Rig Vêda Yajur Vêda Sama Vêda Atharva Vêda |

VÊDÁNGAS

Mantras |

Isha Kêna Mundáka Mandúkya Chandôgya Kausitáki Máitri Svetashvatára |

Source: Adapted from D.S. Sarma (2000, pp.21-29).

It can also be seen in the table above that at the end of each book there is a chapter called Vêdánga, which are the teachings in summary of the doctrine explained throughout the sacred scripture.

It can be seen in Table 2 that the authoritative source called Shruti is classified by Hindus as what is heard or also as divine inspiration. In the Shruti there are also the Kandas which are the practical philosophical-religious teachings to the followers and which expands the desire to know and deepen in the doctrine. Literary texts are the essential foundation for solid knowledge of Hinduism. However, as a secondary source, the analytical narrations of foreign travelers, Greeks, Persians and Arabs about the cited texts would later appear, thus expanding their dissemination of Hinduism.

According to Renou (1990, p.25):

A partir dos séculos mais próximos da nossa era, sucederam-se continuamente textos sobre temas religiosos. Durante muito tempo foram apenas redigidos numa língua única, o sânscrito, mas um sânscrito que se modificara e simplificara pouco a pouco em relação aos mais antigos documentos védicos. No decurso do primeiro milênio da era cristã, o tâmil, língua da família dravidiana, foi usada no sul da Índia; em segundo lugar, o prácrito; a partir de 1100 ou 1200, assistiu-se ao aparecimento de outras línguas dravidianas, tal como de idiomas neo-indianos derivados do sânscrito. Por fim, cerca de 1800, o inglês veio juntar-se às outras línguas. Mas, se se comparar a extrema diversidade das línguas que serviam de expressão ao budismo, verifica-se que o hinduísmo fez apelo a uma gama linguística relativamente pouco extensa.

Table 2. Synoptic Division of Hinduism – Vêdas

| Authorized Source | Holy Book: Veda subchapters |

What do the subchapters mean? |

| SHRUTI (That which is heard, or divine inspiration) |

1 – Karma-kanda 2 – Upásana-kanda 3 – Jñana-kanda |

1 – Ritualist 2 – Meditation and prayer practices 3 – Self-knowledge and self-realization |

Source: Adapted from D.S. Sarma (2000, pp.21-29).

The various authors cited in this work are unanimous in saying that the nature of the Vedas and Agamas is sacred. According to Sarma (1990), Hinduism is Sanátana Dharma, that is, the eternal religion that reveals the sacred way of living, working, the practices of yoga, philosophy and meditation for spiritual self-realization.

Table 3. Synoptic Division of Hinduism – Memory / Interpretive Intellectual Part

| AUTHORIZED SOURCE | SECONDARY SCRIPTURES | ||

| SMRITI (Memory or intellectual or interpretive part made by the sages, theologians and philosophers of Hinduism) |

Smriti (Law Codes) |

Dharma Shastras Shaiva Dharma Shastra |

Authors: 1- Manú 2- Paráshara 3- Yájña Válkya |

| Itihásas (Epics and Religious Notions) |

1. Ramayana (Story of Rama and Sita)

2. Mahabhárata (History of Greater India) |

Livro Especial:

3. Bhagavad Gita (Song of the Lord) |

|

| Puránas (Chronicles and Legends for popular education) |

1. Brahma, Vishnú e Shiva Purána

2. Bhágavata Purána |

Authors:

Manifold |

|

| Ágamas (Denominations and Worship Manuals) |

Denominations: 1.Shaivismo 2. Vishnuísmo 3. Shaktismo 4. Smartismo 5. Brahmanismo |

Who follow:1. Shiva (son) 2. Vishnú (Holy Spirit) 3. Shakti (divine mother) 4. Smarta (non-sectarian) 5. Brahma (father) |

|

Source: Adapted from D.S. Sarma (2000, pp.21-29).

AUTHORIZED SOURCES OF HINDUISM

According to Renou (1990, p. 46), Hinduism can then be defined as the set of appropriate means to reach spiritual liberation. These means are the most diverse. They are sometimes considered to be in a hierarchical relationship with each other; in fact, they never exclude at all.

The Vedas[3] do not suggest that the writing was known to its authors. It was not until the 8th or 9th century BC that Hindu merchants – probably Dravidians – brought from West Asia the Semitic writing, akin to Phoenicia; and from this “brahma script”, as it came to be known, all the alphabets of India were derived (DURANT, 2004, p. 274).

The Vedas are the authoritative and major sources of Hinduism composed in Vedic Sanskrit language. The Vedas are divided into Shruti and Smriti. The Shruti is the division that deals with divine inspiration, what was heard by the sages, therefore, the main authority. The Smriti is the derived authority that consists of expanding and exemplifying the principles of the Vedas (SARMA, 2000).

The Vedas are divided into four great books, namely: Rig Veda, Yajur Veda, Sama Veda and Atharva Veda. Each of these sacred books of Hinduism has important subdivisions called Vêdángas, whose translation means part of the Vedas. They are mantras (hymns), aranyákas, brahmanas (rites), upanishads (spiritual teachings), Upavedas (moral lessons) and ayurveda (ancestral medicine) (SARMA, 2000, p. 21).

The Upanishads present themselves as an important chapter in the transmission of spiritual teaching. The word Upanishad means to sit at the master’s feet.

According to Renou (1990), when certain Upanishads reveal an outline of Hinduism, the great epic poems, and especially the Mahabharata, signal the massive irruption of post-Vedic religion. At this moment, it is understood that Hinduism arises.

Among the Upanishads we find in the Yajur Veda the very important Isavásya Upanishad which, curiously, deals with the doctrine of Jesus. Olson (2014) states that in this important Upanishad, important and relevant facts show a tomb where the body of Jesus is supposedly buried, whom they call Isa or Isha.

Sivananda (2013) states that the Smriti is the memory translated by the Rishis (sages) and the expansion of the Shruti. The revelation of truth has no beginning and no end. Thus, the Vedas have in the subdivision of the Smriti three subchapters of karma-kanda (ritualism), upasana-kanda (practices of prayer and meditation) and jnana-kanda[4] (self-knowledge and spiritual self-realization).

According to Sivananda (2013, p. 34):

O próximo em importância para o Shruti são os Smritis ou escrituras secundárias. São as escrituras sagradas e os códigos de lei dos hindus para conduzir os seguidores ao Sanátana Dharma (religião eterna). Eles dão suporte e explicam detalhadamente os processos ritualísticos chamados de Vidhis dentro dos Vedas. O Smriti Shastra é estabelecido pelos Vedas. O Smriti explica e desenvolve o Dharma. Os códigos de lei foram estabelecidos pelos antigos e renomados Rishis (sábios) Shri Manú, Shri Paráshara e Shri Yájña Válkya (Tradução nossa).

The author makes evident the sacred relationship of the authorized sources that they were explained by three ancient sages, whose recognition is worldwide.

The presentation of the Itihásas, the great and admirable religious epics of India called Ramayána, written by the saint Valmíki, and the Mahabhárata by the sage Vyása, can also be seen in the secondary scriptures, no less important.

According to Sivananda (2013, p. 38), the Ramayána is the first great epic poem that tells the story of Shri Rama, also known as the ideal of being human. Ramayána is the related story of the family of the solar race who descended from Ikshváku, and who were born to Shri Ramachandra, also known as the Avatar of Lord Vishnu.

The Mahabharata is the world epic of the history of the Pandavas and the Kaurávas. Within the Mahabharata we find a special chapter that describes in this historical poem the great war called, the Battle of Kurukshêtra, which breaks the relationship between the Kauráva families and the Pándavas. This special chapter is named after the Bhagavad Gita, which is so important that it has become a separate book (SIVANANDA, 2013).

Also according to Sivananda (2013, p.41), the Puránas, which are classified as chronicles and legends for popular education. There are five divisions in the Puránas, and they are historical, cosmological, cultural, philosophical and theological. The Puránas are classified in approximately 108 books.

The Puránas are also considered instruments for popular education, following epics of great importance and showing legends, genealogies of kings and reigns, presenting a rich historical material. The authors of the Puránas are hundreds and it would not even be appropriate to add them here.

Then there is another division of the Smriti called Agamas. These secondary scriptures specify the manuals of religious worship and the hundreds of Hindu denominations that exist in India.

According to Sarma (2000, c.V, p. 26):

Outra classe de escrituras populares consiste nos chamados Ágamas. Esta palavra é usada para designar as escrituras que lidam com o culto de um aspecto particular de Deus e receitam cursos detalhados de disciplinas (Tapas, em sânscrito) para o crente. Assim como deidade adorada é Vishnú ou Shiva, ou Shakti, os Ágamas acham-se divididos em três classes ortodoxas que fizeram surgir os três principais ramos do Hinduísmo, a saber: Vaishnavismo, Shaivismo e Shaktismo. O Vaishnava Ágama glorifica Deus como Vishnú. O Shaiva Ágama O glorifica como Shiva, e fez surgir um importante colégio de filosofia conhecido como Shaiva Siddhanta. E o Shakta Ágama ou Tantra glorifica o Supremo como a Mãe do Universo sob um dos muitos nomes da Deví.

PHILOSOPHICAL SCHOOLS OF HINDUISM

Finally, the Darshanas also known as philosophical schools or way of life of Hinduism are contemplated. Each school, in its own way, seeks to develop, systematize and correlate the various parts of the Vedas (SHARMA, 2002).

The various authors cited in this work agree that the philosophical schools or way of life of Hinduism are addressed to students and appeal to their logical knowledge, while the Puránas and Agamas are addressed to the people and appeal to the imagination of their feelings.

Box 4. Darshanas: Philosophical Schools of Hinduism.

| Authorized Source | Dárshana | Founder | Book of precepts |

| Dárshana (Philosophical School or point of view) |

1.) Nyáya 2.) Vaishêshika 3.) Sámkhyá 4.) Yoga 5.) Mimánsa 6.) Vêdánta |

1.) Shri Gautama 2.) Shri Kanáda 3.) Shri Kapíla 4.) Shri Pátañjali 5.) Shri Jaimíni 6.) Shri Badarayána |

1.) Nyáya sutra 2.) Vaishêshika sutra 3.) Samkhyá sutra 4.) Yoga sutra 5.) Mimánsa sutra 6.) Vêdáta sutra |

Source: Adapted from Swami Sivananda (2013, pp. 47 – 53).

As can be seen from the table above, each Darshana consists of a number of sutras or aphorisms attributed to the founder of the school. To these sutras is attached an authoritative commentary from a later time; and in this original commentary we have observations, notes and later comments (SARMA, 2000, p. 27).

It is understood, therefore, that the first four Darshanas (Nyáya, Vaisheshia, Sámkhyá and Yoga) are systems based on the Vedas and they take forward every possibility of awakening consciousness. And why do you see yourself like this? It seems to us that the purpose of Hinduism’s Darshanas is to make man a perfect spirit like God and with Him.

FUNDAMENTAL BELIEFS

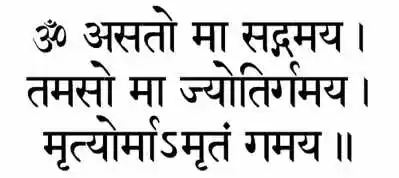

According to Yogi (2017), the real cause of human suffering remains their spiritual ignorance and, therefore, the lack of guidance and guidance. The central point of Hindu thought states in the Brihadaranyáka Upanishad scripture:

Table 5. Central Point of Hindu Thought

| Brihadaranyáka Upanishad | ||

| Sanskrit/ Devanágari | English transliteration | Translation to English |

|

OM Ásato mā sat gamayá Tamaso mā jyotir gamayá Mṛtyor mā amṛtaṃ gamayáShanti, Shanti, Shanti |

It takes me from unreality to reality. Lead me from darkness to light. Lead me from death to immortality. Peace, Peace, Peace. |

Source: Adapted from Shri Swami V. Yogi (2017, p. 5).

The term Dharma means law or duty. According to authors Coleman (2017) and Horsley (2016), Dharma is a spiritual duty and in itself maintains social harmony between people. Dharma supports the world, ensures the preservation and maintenance of society. Dharma is defined as what is ordained by the Vedas and is not, ultimately, a product of suffering (SATCHIDANANDA, 2012).

Yogi (2005) states that it is essential to be without obstacles to the spiritual path and that these obstacles are classified into eight, namely: vyádhi (disease), styána (apathy), samsáya (doubt), pramáda (negligence), alásya ( laziness), bhrantidárshan (mistaken judgment), anavashtitha (instability), and rágaprakríti (material attachment).

OBSTACLES TO THE SPIRITUAL PATH

Box 5. Vikshepas: Obstacles to the Spiritual Path

| Vikshêpas | ||

| Sanskrit term | Translation | Philosophical Explanation |

| Vyádhi | Disease | Illness disperses attention. The sick commonly requires help and depends on external forces. The search for a cure, the preoccupation with pain, the impotence in the face of the disease and the process towards death distract attention and deviate from the path of self-knowledge and self-fulfillment. |

| Styána | Apathy | A person is apathetic when he has no strength or energy, when he lacks vitality. The apathetic is indifferent, is lacking in affection, is insensitive and despondent. |

| Samsáya | Doubt | Doubt prevents our confident surrender. Doubt must not lead to skepticism, but to philosophical questioning. |

| Pramáda | Pramáda | Neglect leads to the failure of any project. Without motivation, there will be no attentive mind. |

| Alásya | Laziness | Laziness is also lethargy, indolence, or desamino. It is mental inertia and inactivity, and causes alienation and inaction. |

| Bhrantidárshan | Misperception | Without the correct perception of things we are led to lose critical sense, we are led to error and illusion. |

| Anavashtitha | Instability | Instability leads to insecurity and mental fluctuation, and in turn, to imbalance and failure. |

| Rágaprakríti | Material attachment | Attachment to material things, including intellectuals, produces envy, dispute, distrust and fear of loss. |

Source: Adapted from Shri Swami V. Yogi (2005, pp. 78 – 82).

Therefore, it is clear to the various authors cited that the vikshepas or obstacles to the spiritual path are the greatest impediments to the spiritual advancement of humanity.

According to Yogi (2017), Hinduism guides its followers not to accept vices of any nature, as well as human distortions of any species and nature. They do not admit alcohol, tobacco, drugs, sexual abuse, prejudice of any kind, theft, possessiveness, hatred, adultery, abortion, etc. It is the conduct of this more rigid and committed behavior towards life that shows a serious Hinduism with spiritual precepts.

HINDU RELEASE AND DETACHMENT

Hindus believe that the periods of human life for its natural and balanced development are developed every seven years. Sivananda (2013, p. 185) presents the phases of life and denominates them as Purusárthas, namely: Dharma (law, duty), Artha (material achievement), Kama (mental and emotional achievement) and Moksha (liberation in life).

Table 5. Purusharthas: The Stages of Life, according to Hinduism.

| PURUSHARTHAS (The four paths of life) |

|

| Dharma | The law and duty above all. |

| Artha | Conquest of the material to learn, live, serve, take care of the family and do the maintenance and management of things. |

| Kama | Conquer desire, love, human emotion. |

| Moksha | Free yourself in life, naturally detaching yourself from things and turning your attention to God. |

Source: Adapted from Shri Swami V. Yogi (2005, pp. 87).

PURUSHARTHAS: STAGES OF LIFE

Thus, we see here an interesting philosophical-religious position. Sivananda (2013) talks about Moksha, that is, liberation in life. But how to achieve this? As seen in Sarma (2000), the Sámkhyá, Yoga and Vêdánta philosophical schools of Hinduism seek human liberation in life, that is, they do not believe that we need to die to free ourselves, but they also do not rule out this hypothesis. We call this stage Purusharthas or stages of life.

It is the duty of the human being to reach this state of consciousness. Therefore, we understand that it is a human mission to elevate ourselves spiritually to discover paradise on earth. The human being who reaches this state of consciousness is called a jivamukti (realized) or buddha (enlightened). Dozens of Upanishads clearly mention and describe this state of spiritual consciousness (SIVANANDA, 2013).

Yogi (2017) states that the mind is the gateway to this planet we live on. The mind is part of the Ahamkára (ego) and is an instrument for the search and rescue of spiritual knowledge. The mind can be, according to him, the source of liberation or slavery, depending on how we condition it.

Collaborating, Sivananda (2013) shows the Hindu Dharma speaking of ethics, spirituality and religion, and the benefits of every human being to follow a straight and righteous path.

HINDU CODE OF ETHICS

The Hindu ethical code observes the Yama (personal conduct) and the Niyama (social conduct). It affirms that every human being must serve, love and fulfill. Ethics, therefore, is a process of purification and advancement to God. Subramuniyaswami (2000), world leader and priest of Hinduism, then presents a strict code of ethics and behavior that serves as a safe-conduct for an unblemished and spiritual behavior to indoctrinate the human mind. This code of ethics is composed of ten ethical norms of the human being towards society and ten more ethical norms towards oneself.

Box 6. Yama and Niyama: The Ethical Norms of Hinduism.

| Hindu Code of Ethics | |

| YAMA (Ethical norms with society) |

NIYAMA (Ethical standards with yourself) |

| Ahimsa (no violence) | Saucha (purity) |

| Sátya (veracity) | Santosha (contentment) |

| Ashtêya (don’t steal) | Tapas (discipline) |

| Aparigráha (non-possessiveness) | Swadhyáya (self study) |

| Brahmachárya (spiritual awareness) | Ishwarapranidhana (spiritual surrender) |

| Kshama (tolerance, patience, understanding) | Hri (modesty) |

| Dayá (compassion) | Danam (generosity) |

| Sakahára Mitahára (vegetarianism and moderate appetite) |

Mativráta (inner faith) |

| Arjáva (simplicity and prudence) | Jápa (daily recitation) |

| Vivêka (discernment) | Yájña (sacrifice; sacred office) |

Source: Adapted from S. Subramuniyaswami (2000), Himalayan Academy.

CONCLUSION

The investigation of the literature referenced in this article showed that the importance of the spiritual precepts advocated by the largest religion in India, Hinduism, are the fundamental pillars of this millenary religion and philosophy for the development and fulfillment of human destiny on earth, equally and positively influencing other mystical segments around the world.

The various texts commented and the various authorities researched clearly and convincingly showed that the precepts are intended to guide approximately one billion and three hundred million faithful and followers around the world, and that it increases day by day, and still, made it possible to identify, analyze, evaluate and understand in a clear and objective way that the West is transforming its way of thinking, feeling and seeing the world day by day, basing itself on Eastern precepts, and no less scientific.

As researchers are gradually adjusting to the electronic environment, in the creation of websites, blogs and other media in the production of scientific articles that address Hinduism and its impact on world society, it emerges, then, as a promising area in several fields of knowledge. for research and science, especially in theology and philosophy, with practical applications for society and religious communities across the planet.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

AQUINO, Felipe. Minha Igreja. Cléofas, 2015.

ADELE, Deborah. The Yamas e Niyamas: exploring Yoga’s Ethical Practice. On-World Bound Books, 2009.

CHAMPLIN, Russel Norman. Enciclopédia de Bíblia, Teologia e Filosofia. United Press, 2002.

COLEMAN, Cassie. Hinduism: a comprehensive guide to the Hindu Religion Gods, Beliefs, Rituals and History. Create Space Ind. Publishing, 2017.

DAS, Rasamándala.The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A comprehensive guide to Hindu history and philosophy, its traditions and practices, rituals and beliefs. Lorenz Books, 2012.

DEDEREN, Raoul. Handbook f Seventh-day Adventist Theology. Christ: Person and Work. Droz, 2014.

DIERKEN, Jörg. Teologia, Ciência da Religião e Filosofia da Religião: definindo suas relações. Disponível em: <http://revistaseletronicas.pucrs.br/ojs/index.php/veritas/article/viewFile/5071/3736>. Acesso em 29 out. 2018.

DONIGER, Wendy. On Hinduism Paperback. Oxford University Press, 2016.

DURANT, Will. Nossa Herança Oriental. Record. 2004.

EASWARAN, Eknath. The Bhagavad Gita: Easwaran’s Classics of Indian Spirituality. Nilgiri Press, India, 2007.

FLOOD, Gavin. An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press, 1996.

GAARDER, Jostein. El Libro de las Religiones. Ed. Siruela, 2016.

HILL, J. História do Cristianismo. São Paulo, Ed. Rosari, 2008.

HINDUISM TODAY MAGAZINE – Himalayan Academy – Disponível em: https://www.hinduismtoday.com/modules/wfchannel/index.php?wfc_cid=5 . Acesso em 28 out. 2018

HORSLEY, Mary; BARTLETT, Cynthia. Religious Studies: Hinduism. Oxford Publications, 2016.

ISAVÁSYA UPANISHAD: The Doctrine Immanence of Jesus. Desenvolvido por Prof. Minan. M.M. India, New Delhi. Disponível em: <http://www.talentshare.org/~mm9n/articles/Isovasya/Prof_%20M_M_Ninan%20-Isovasya%20Upanishad.htm >. Acesso em 12 nov.2018.

JARDIEL, Enrique Gallud. El Hinduismo en sus textos esencialies. Ed. Verbum, 2016.MALVIYA, Chanchal; NIKAN, Ravi; Purusharth: The Natural Wheel of Progress. Aryavarta Publ. 2016.

KREEFT, Peter; TACELII, Ronald. K. Handbook of Catholic Apologetics: Reasoned Answers to Questions of Faith. Ignatius Press, 2009.

______________. Forty Reasons I Am a Catholic. Sophia Inst. Press, 2018.

KERTEN, Holger. Jesus Lived in India: His Unknown Life Before and After the Crucifixon England, Element Book, 1986.

MONIER-WILLIAMS SANSKRIT-ENGLISH DICTIONARY. Desenvolvido pela Oxford University. Disponível em: < http://www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de/monier/veda >. Acesso em 13 nov.2018.

OLSON, Suzanne. Jesus in Kashmir: the lost tomb. Booksurge, 2014.

RENOU. Louis. As Grandes Religiões do Mundo: Hinduísmo. Verbo, 1990.

ROHDEN, Huberto. Filosofia Cósmica do Evangelho. Martin Claret, 2016.

_______________. Sermão da Montanha. Martins Claret, 2015.

_______________. Assim dizia o Mestre. Martins Claret, 2014.

SARMA. D. S. Hinduísmo e Yoga. Freitas Bastos, 2000.

SIVANANDA, Swami. All About Hinduism. Divine Life Society, Shrinagar, Connaught Place. India, 2013.

SATCHIDANANDA, Sri Swami. Yoga Sutras of Pátañjali. Integral Yoga Publications, 2012.

SHARMA, Manju Lata. The Four Purusharthas in the Puranas. Parimal Ed, 2002.

SIVANANDA, Swami. All About Hinduism. Divine Life Society, Shrinagar, India, 2013.

SIVALOGANATHAN, Kandiah. A brief introduction to Hinduism. Zorba Books, 2017.

SINGH. Dharam Vir. Hinduism an introduction. Travel Wheels. 2003.

SMITH, Huston. The Religions of Man. Ishi Press. 2013.

SHELLEY, B. L. História do Cristianismo ao alcance de todos. São Paulo, Shedd, 2004.

SUBRAMUNIYASWAMI, Satguru Sivaya. How to become a Hindu: a guide for seekers and bord hindus. Himalayan Academy, EUA/India, 2000.

TEIXEIRA, Faustino. O lugar da Teologia na Ciência da Religião. In: Faustino Teixeira (org.) As Ciências da Religião no Brasil. Op. cit., pp. 300-301.

VIDYALANKAR, Pandit. The Holy Vedas. Clarion Books, 1998.

VISWANATHAN, Edakkandiyil. Am I a Hindu? Rupa Company, India, 2003.

VIVEKJIVANDAS, Sadhu. Hinduism: An Introduction. Swaminarayan, 2011.

YOGI, Shri Swami Vyaghra. Yoga Sutra de Shri Pátañjali. Vidya Press, 2017.

______________________. Palavras de Sabedoria. Vidya Press, 2005.

ZILLER, Urbano. Filosofia da Religião. São Paulo, Paulus, 1991.

APPENDIX – FOOTNOTE

3. The Sanskrit word Veda must be pronounced with the vowel “ê” closed. Furthermore, every Sanskrit word ending in a vowel “a” is masculine. Therefore, the pronunciation must be “the Vedas”, not “the Veda”. VEDA. In: SANSKRIT-ENGLISH DICTIONARY, by Monier-Williams, Oxford University, 2008, revision. Disponível em: <http://www.sanskrit-lexicon.uni-koeln.de/monier/> Acesso em 13 nov.2018.

4. The Sanskrit word Jnana means “to have knowledge, understanding”; should be pronounced as in Spanish “señor” or “senior”. JÑANA. In: BABYLON. Disponível em: < https://translation.babylon-software.com/english/jnana/ >. Acesso em 13 nov.2018.

[1] Specialist in Developmental Psychology; Degree in Philosophy; Bachelor in theology; Specialist in Psychoanalysis.

[2] Professor, Master in Biotechnology.

Sent: January, 2019

Approved: February, 2019