ORIGINAL ARTICLE

MELO, Márcia Luz de [1]

MELO, Márcia Luz de. Religious teaching in public schools and the principle of secularism. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year. 08, Ed. 04, Vol. 04, pp. 113-125. April 2023. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/science-of-religion/principle-of-secularism, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/science-of-religion/principle-of-secularism

ABSTRACT

The Brazilian educational system has never been alien to the many movements of society, so it could not be distanced from the religious phenomenon either, since the school is a part of the community and all the expressions of a society are found in it, even if in smaller proportion. The present article in question seeks to carry out a discussion about the importance of respecting the various religious beliefs existing in the country. In the development of this research, which was built through the analysis of bibliographies and analyzes of legislation that legitimize religious teaching, the following question is discussed: can the professor of the religious teaching discipline, participant of an integral formation, be able to teach classes of this discipline without be biased, considering the context of religious diversity and existing legislation in the country? Finally, it is understood that, although criticized for the risk of being able to become a violator of human rights, religious education, obeying the criteria established in legislation, including creating legislation that favors the training of educators for this purpose, can become in an important mechanism for improving peaceful coexistence and respect for the pluralities that form the identities of the subjects that make up Brazilian society.

Keywords: Religious teaching, Secularity, Formation.

1. INTRODUCTION

This article addresses the theme of inserting religious education in public schools in view of the constitutional principle of the Secular State, the challenges and the importance of teacher training.

Its main objective is to carry out a discussion about the importance of respecting the different religious beliefs existing in the country. In this way, it seeks to answer the following question: could the teacher of the Religious Education discipline, participant of a comprehensive training, teach classes in this discipline without being biased, considering the context of religious diversity and the existing legislation in the country?

The theme “religious teaching in public schools in Brazil” has been the result of much academic research, especially in recent decades.

It was common, in the development of this research, which was built through the analysis of bibliographies and analyzes of legislation that legitimize the existence of religious teaching in the school grid, to find studies that deal with the development of the discipline, but few productions that deal with related aspects to teacher training, which motivated the study on the subject.

During this study, it was also possible to access literature and authors who defend the relation of the secular State and the existence of religious teaching in public schools, as well as the knowledge of those who ponder and are afraid of possible contradictions to the legality of this teaching, even emphasizing that this discipline puts at risk the right of citizens to freely express their religion and creed.

Por estar implicada com a formação da consciência de crianças e adolescentes, bem como com o exercício desses e de outros direitos, a questão do ensino religioso nas escolas públicas é um dos pontos mais sensíveis na defesa da laicidade do Estado brasileiro e de direitos fundamentais da cidadania brasileira, bem como dos direitos humanos. (FISCHMANN, 2008, p. 9).

On the other hand, we had access to authors such as Lafer (2007) and Martins (2009), who admit and understand that the secular State does not make the existence of religious teaching in public schools unfeasible, since, from the school perspective, these authors understand , the secular State is one that does not oblige following a religion, but proposes knowledge of different religious cultures, such as what was proposed by the Curriculum Guidelines (BRASIL, 1998) and by the Guidelines on Religious Education (BRASIL, 2010) , from the Ministry of Education and Culture (MEC)[2].

Regarding the relationship of the secular State with education, the following position is found in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

Toda pessoa tem direito à liberdade de pensamento, consciência e religião; este direito inclui a liberdade de mudar de religião ou crença e a liberdade de manifestar essa religião ou crença, pelo ensino, pela prática, pelo culto e pela observância, isolada ou coletivamente, em público ou em particular (ONU, 1948).

Thus, it is clear that the multiplicity of opinions about religious education in the Brazilian educational system comes from the polysemy of concepts that encompass the understanding of what a secular state is and the successive legislation on religious education in Brazil.

The answer found was, above all, the investment in the training of the teaching staff, understood, in most literature, as responsible for the quality of teaching that is proposed to be carried out.

Furthermore, in order to teach this discipline, it is necessary for the educator to have a cultural and conceptual background, which includes themes that strengthen concepts confluent with the theme.

2. UNDERSTANDING THE QUESTION

The word “secular” comes from the Greek laikós, which means “people” (LAICO, 2020). In antiquity, more specifically in the Middle Ages, the term was coined to represent those who, despite belonging to the church, did not belong to the clergy.

The principle of secularity is one of the primacies of modern States, and the beginning of discussions about it is attributed to the French State, with its historical construction dating back more than a century. Secularity is a concept born of the separation between State and Church, the conception of a secular State was born of a long process of secularization, of an emancipation and progressive construction, through a distance from dogmas, the clergy and, above all, the power of the Catholic Church, philosophical and Enlightenment ideals, gaining importance under movements of the time, such as the Protestant Reformation.

In Brazilian constitutions, the word “secular” appears as a principle to be followed, and represents/signals the separation between church and state things. This process began under French influence, starting in 1882, with Ruy Barbosa’s suggestion of having freedom of teaching. It should be remembered that, before that, the religious system was massively influenced by the Catholic Church, being modified in the course of political and economic movements, until reaching what we have today, with the 1988 Constitution, the incisive concept, constant in the article 5 of CF/88:

Artigo 5º, inciso VI, que dispõe ser “inviolável a liberdade de consciência e de crença, sendo assegurado o livre exercício dos cultos religiosos e garantida, na forma da lei, a proteção aos locais de culto e suas liturgias” (BRASIL, 1988).

Regarding the principle of secularism, Debray (2002, p.23) says that its principle takes place in freedom of conscience, that is, it “does not present itself as a spiritual option among the others, it is what makes its coexistence possible, because what is common in right to all men must be the measure of what separates in fact.”

Rios (2006, p. 3466) adds that “if the school intends to form the conscious citizen, it needs to help students in reading the culture of their country, it needs to teach them how to give coherence to the world. This is everyone’s responsibility”.

In this sense, the school, among other attributions, has the duty to mediate the cultural constructions created from human relationships in the most diverse social contexts and, in this sense, provide spaces for knowledge about diversities.

For Amaral Júnior (2008, p. 14), the relationship between the secular State and education is inserted in the field of human rights, he points out that: “In this context, the theme of religious education is strictly related to the issue of human rights and to the preservation of freedom in an essentially plural world.”

Thus, by affirming the importance of religious education and its theoretical and practical perspectives in public education, it also implies the resumption of the critical debate on religions and the cultural meanings that underlie the historical origin of religious diversity. For Silva (2004, p.2):

[…] as religiões são parte importante da memória cultural e do desenvolvimento histórico de todas as sociedades. Desse modo, o ensino de religiões (e não de uma religião) na escola não deve ser feito para defesa de uma delas, em detrimento de outras, mas discutindo princípios, valores, diferenças e tendo em vista – sempre – a compreensão do outro.

However, there is an issue that is present in almost all the literature used for the construction of this article: how to make the religious educator keep distance from his beliefs and convictions when teaching classes in this discipline, even observing human rights precepts ?

3. THE HISTORICAL PATH OF RELIGIOUS EDUCATION IN BRAZIL

Religious teaching has always been present in Brazilian schools. The first idea of religious teaching in Brazilian public education appeared in the context of the country’s colonization, when the Jesuits conducted a missionary project and resorted to education in order to inculcate Catholic dogmas. (SAVIANI, 2008).

This way of educating remained until the middle of the 18th century (1759), changing only after the expulsion of the Jesuits, by Marquês de Pombal, when a new educational perspective was brought to the country, a secular education and with a perspective, educational philosophy , which aimed to implement the humanist tradition in education, later opening up to the evolution brought by the royal family, which, in 1808, arrived in Brazil and expanded these strategies, especially to meet the needs of the court.

It was only after the proclamation of the republic and the elaboration of the first Constitution that a movement to organize the Brazilian educational system emerged, in which the provinces began to assume primary and secondary education, while higher education was assumed by the central government. Religious education, in this period, despite being precarious, began to be outlined, especially with the support of Freemasonry and its liberal ideals.

In this context, the 1824 Constitution sealed the union between crown and religion, and relations between State and Church were also accentuated in the educational field, since the Instruction Law of 1827 addresses religious teaching in the following terms: “Art. 6 – The teachers will teach reading, writing, the four operations of arithmetic […] and the principles of Christian morals and Roman Catholic and Apostolic doctrine […]” (BRASIL, 1827, online). This form of organization of the imperial school remained inconstant until the Proclamation of the Republic, in 1889.

It was only with the advent of the republic and with strong positivist and military influence that a new educational reality was created: the secularization of Brazilian education. This movement was much questioned by the Church, however, the Constitution of 1891 regulated the separation between these institutions and prohibited the subsidization, restriction and maintenance of cults by the State (BRASIL, 1891). With this determination, between 1889 and 1930, the Church expanded the creation of its own schools through religious congregations.

From 1930, with the arrival of Getúlio Vargas to power, the church regained a little more influence, especially with pressure movements, which meant that, in the 1934 Constitution, the discipline of religious teaching had the its official return to the grid of public schools in the country. Legislation established that the offer of the subject was mandatory and optional for students, with the novelty of including this subject in vocational schools (BRASIL, 1934). Here, as in the beginning, there is a new alliance between State and Church.

However, this alliance is broken from 1937 onwards, with the adoption of a dictatorial posture by the government, which suspends the provisions of the Constitution, among them, those referring to individual freedoms and those referring to mandatory discipline in school curricula.

In 1945, in the context of the Estado Novo, there was a proposal that further weakened the insertion of religious teaching as a curricular subject, since it became a non-compulsory subject that could be offered outside school hours.

After the post-dictatorial period (1946-1964), the country was marked by the organization of a new Constitution, characterized by liberal principles, due to the country’s alignment with the USA. This liberal and democratic ideological influence meant that the discipline of religious teaching was maintained as mandatory in public schools, being provided according to the student’s religious confession, guaranteeing religious freedom, however its enrollment would be optional.

The Brazilian Constitution of 1988 makes reference to religious education, however, the characteristics of previous constitutions are repeated, of a subject to be taught within the school hours of elementary school and optional enrollment, without cost to the State (BRASIL, 1988 ).

The presence of this theme in the Constitution opened possibilities for this discipline to also be considered in Law nº 9394/96, which deals with the Guidelines and Bases of Education (LDB)[3]. In it, religious teaching must have an ecumenical character, optional enrollment and must be based on respect for religious freedom, deserving equal treatment in the overall teaching-learning process (BRASIL, 1996).

But, despite this new milestone, problems still persisted, since the phrase “without cost to the State” implied the teaching of classes by volunteers, which made the applicability of the discipline difficult.

I. Denominations could find loopholes to teach the discipline in a catechetical format, without respecting the religious diversity that a classroom presents.

II. Educators, once they are volunteers, would not have the financial conditions to undertake continuing education.

However, due to these obstacles to the implementation of the discipline, proposals were prepared by the national congress to amend the LDB, in particular article 33, which deals with religious teaching, so this article, after these proposals, was changed to the following form:

Art.: 1º – O art. 33 da Lei nº 9.394, de dezembro de 1996, passa a vigorar com a seguinte redação:

Art. 33 – O Ensino Religioso, de matrícula facultativa, é parte integrante da formação básica de cidadão, constitui disciplina dos horários normais das escolas públicas de ensino fundamental, assegurado o respeito à diversidade cultural religiosa do Brasil, vedadas quaisquer forma de proselitismo.

Parágrafo 1º – Os sistemas de ensino regulamentarão os procedimentos para a definição dos conteúdos do ensino religioso e estabelecerão as normas para a habilitação e admissão dos professores.

Parágrafo 2º – Os sistemas de ensino ouvirão entidade civil, constituída pelas diferentes denominações religiosas, para a definição dos conteúdos do Ensino Religioso. (BRASIL, 1996).

The new wording of the LDB reaffirms the discipline as part of the curriculum of elementary schools and places it on the same level as other disciplines, however, it still does not regulate important factors, such as the contents that should be taught and the standardization of qualification of these educators.

The National Education Council (CNE)[4] manifested itself and instituted curriculum guidelines, recognizing religious teaching as an area of knowledge, but there was no consensus with the Higher Education Chamber (CES/CNE), especially regarding the academic training of teachers.

Based on this conflicting situation, the Permanent Forum on Religious Education (FONAPER)[5] was organized, which, in partnership with experts, prepared the National Curriculum Parameters for Religious Education (PCNER)[6], which proposed professional training for religious education. This proposal contemplated the holding of courses, seminars and congresses, in order to encourage and bring about discussions that would support teaching.

4. LEGISLATION AND TRAINING OF TEACHERS IN RELIGIOUS EDUCATION

There have been many transformations, especially in the educational field. Degrees, such as, for example, in Pedagogy, have modified their contents, diversified and encompassed historical, philosophical, anthropological, economic and cultural knowledge. In this educational context, there is also religious teaching.

This discipline, since its implementation, has been the target of polemics and controversies of various natures. It is a fact that some Brazilian states relegate the discipline of religious teaching, leaving it in the background when it comes to the issue of curriculum and content, and that others still maintain the confessional model.

As previously explained, this discipline was guaranteed, by the Federal Constitution of 1988, as a curricular component. The LDB, Law nº 9394/96, ensured it in fundamental education (Article 33, with new wording given to the aforementioned article by Law nº 9475/97) (BRASIL, 1996) and the National Council of Education, by its Opinions 4/1998 and 4/2010, established the National Curriculum Guidelines for Elementary Education, in which it defined Religious Education as one of the ten areas of knowledge (BRASIL, 1998, 2010).

Thus, there is a gradual opening, for States and Municipalities, for the creation of positions of professor of religious education, however, between its implantation and effectiveness as a discipline, there were omissions and many gaps, which mainly involved governmental actions to ensure specific training in this area for teachers at different levels.

The LDB itself, Law Nº 9394/96, regarding teacher training, says, in its article 62:

A formação de professores para atuar na educação básica far-se-á em nível superior, em curso de licenciatura, de graduação plena, em universidades e institutos superiores de educação, admitida, como formação mínima para o exercício do magistério na educação infantil e nas quatro primeiras séries do ensino fundamental, a oferecida em nível médio, na modalidade Normal. (BRASIL, 1996).

It is noticed that the LDB emphasizes teacher training, whether in the normal modality or in a degree course, but it does not determine, nor prevent, the offering of a specific course for the training of teachers of religious education. However, the new wording given to article 33 of the LDB, by Law nº 9475/97, standardizes the procedures for defining the contents of religious teaching and establishes the norms for the qualification of teachers.

Affirming, now, that any offer of training course for teachers of religious education must observe this legal basis given by the constitutions, by the LDB and by opinions and resolutions of the education systems (federal, state and municipal resolutions).

From this legislation, there is a legal direction that the offer of qualifications in religious education cannot lead to any form of proselytism, and must ensure respect for religious cultural diversity, not being restricted to a particular religion.

The National Curriculum Parameters for Religious Education (PCNER) were constructed with a view to understanding the different meanings of religious symbols in the lives and coexistence of people and groups, for this, it established axes of approaches (religious cultures and traditions, sacred scriptures and/or oral traditions, theologies, rites and ethos). There is an effort to work the discipline in a multicultural perspective, demonstrating it as a religious phenomenon and an integral part of the culture of different peoples.

In this sense, knowing that teachers can interpret and make representations about the same issue in a different way, how to guarantee the performance of teaching in accordance with legal prescriptions, guaranteeing respect for all religions represented in the classroom, if not through training that contains arguments that favor this culture?

The answer that can be envisioned, through understanding the situation of religious education and the training of teachers for this discipline, is that, before any judgment, it is necessary to understand the disputes in both the political and religious fields, especially in what concerns it concerns the performance of sectors of the Catholic Church and the multiple religious segments that have Protestants as the majority, and their reflections in the educational and even moral field. The advances of the last decades are recognizable, but there are also the setbacks that culminated in the loss of autonomy for the political and religious fields. Currently, there is a conservative wave, which admits only one truth, which is yours.

5. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Historically, the conception of religious teaching has changed in the country, especially after the enactment of the new wording of article 33 of the Law of Guidelines and Bases of Education.

For religious teaching, this new wording was a milestone, as it favored the pedagogical work, the organization of the subject and its methodologies, and provided the student with knowledge and understanding of the religious phenomenon as a cultural and social factor.

However, this story is permeated with misunderstandings, because, despite being provided for by law, there are still many problems in relation to this discipline, especially with regard to the states of Brazil, in which confessional teaching is adopted, interconfessional or history of religions as a practice, still causing constraints and violations.

What can be seen in the researched bibliographies is that the trajectory of religious teaching, until it became a school subject, as well as its permanence in the curriculum, is also permeated by social and historical construction, by power relations and by the interests of the country.

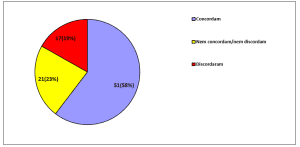

Although predominantly Christian, the Brazilian population is permeated by a plurality of religious beliefs of different origins. Data from the 2010 Census indicate that 86% of the Brazilian population declared themselves Christian (Catholics and Protestants), but also identified, among the remaining 14%, about 40 religious groups from other matrices in the country (IBGE, year).

While this existing plurality is capable of making respect for difference possible, it is also a catalyst for violence and intolerance, even more so considering the growing expansion of religious aspects and, consequently, the emergence of a radicalization and foundation of a market that disputes faithful , forcing religion to base itself discursively, even aggressively in relation to other aspects.

There is, in the education system, a miscellany of contents that are taught by teachers, among them religious education. Through the various literatures, one can see how difficult it is to understand and translate in an understandable way the theoretical and conceptual dimension of the religious phenomenon, which needs to be understood as a science with principles and methods.

There is a need for greater investment, both in initial and continuing education, as there is a lack of qualified teachers and a less confused educational policy in relation to the epistemology of this area of knowledge, in addition to aspects related to the stability of these educators, who, in many states, are temporary teachers.

Finally, it is understood that, although criticized for the risk of being able to become a violator of human rights, religious education, obeying the criteria established in legislation, including creating legislation that favors the training of educators for this purpose, can become in an important mechanism for improving peaceful coexistence and respect for the pluralities that form the identities of the subjects that make up Brazilian society.

REFERENCES

AMARAL JÚNIOR, Alberto do. Direitos humanos e a Constituição brasileira de 1988. In: FISCHMANN, Roseli. (Org.). Ensino religioso em escolas públicas: impactos sobre o Estado Laico. São Paulo: Factash, 2008.

BRASIL. Lei de 15 de outubro de 1827. Manda crear escolas de primeiras letras em todas as cidades, vilas e lugares mais populosos do Império. Rio de Janeiro: Chancellaria-mór do Imperio do Brazil, 1827. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/lim/LIM..-15-10-1827.htm. Acesso em: 29 mar. 2023.

BRASIL. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil de 1988. Brasília, DF: Senado Federal, 1988.

BRASIL. Constituição da República dos Estados Unidos do Brasil (de 24 de fevereiro de 1891). Nós, os representantes do povo brasileiro, reunidos em Congresso Constituinte, para organizar um regime livre e democrático, estabelecemos, decretamos e promulgamos a seguinte. Rio de Janeiro: Sala das Sessões do Congresso Nacional Constituinte,1891. Disponível em: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao91.htm. Acesso em: 29 mar. 2023.

BRASIL. Constituição da República dos Estados Unidos do Brasil (de 16 de julho de 1934). Nós, os representantes do povo brasileiro, pondo a nossa confiança em Deus, reunidos em Assembléia Nacional Constituinte para organizar um regime democrático, que assegure à Nação a unidade, a liberdade, a justiça e o bem-estar social e econômico, decretamos e promulgamos a seguinte. Rio de Janeiro: Sala das Sessões da Assembléia Nacional Constituinte, 1934. Disponível em: https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao34.htm. Acesso em: 29 mar. 2023.

BRASIL. Lei nº 9.394, de 20 de dezembro de 1996. Estabelece as diretrizes e bases da educação nacional. Brasília, DF: Diário Oficial da União, 1996. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l9394.htm. Acesso em: 29 dez. 2019.

BRASIL. Resolução CEB nº 3, de 26 de junho de 1998. Institui as Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais para o Ensino Médio. 1988. Disponível em: http://portal.mec.gov.br/cne/arquivos/pdf/rceb03_98.pdf. Acesso em: 29 mar. 2023.

BRASIL. Ministério da Educação. Resolução nº 4, de 13 de julho de 2010. Define Diretrizes Curriculares Nacionais Gerais para a Educação Básica. 2010. Disponível: http://www.prograd.ufu.br/sites/prograd.ufu.br/files/media/documento/resolucao_cneceb_no_4_de_13_de_julho_de_2010.pdf. Acesso em: 29 mar. 2023.

DEBRAY, Regis. L’Enseignement du fait religieux dans l’école laïque. France: Ministère de l’éducation nationale, 2002.

LAFER, Celso. Estado laico. O Estado de São Paulo, p. 1-2, 2007.

LAICO. In: DICIO, Dicionário Online de Português. Porto: 7Graus, 2020. Disponível em: https://www.dicio.com.br/laico/. Acesso em: 27 fev. 2023.

ONU – ORGANIZAÇÃO DAS NAÇÕES UNIDAS. Declaração universal dos direitos humanos. 1948. Disponível em: http://portal.mj.gov.br/sedh/ct/legis_intern/ddh_bib_ inter_universal.htm. Acesso em 10 de dez de 2019.

RIOS, Denise Cristiane. Ensino religioso e a realidade brasileira: identidade e formação docente. In: VI EDUCERE – Congresso Nacional de Educação da PUCPR – PRAXIS, Curitiba: Champagnat, 2006. Disponível em: http://www.pucpr.br/eventos/educere/educere2006/anaisEvento/docs/CI-250-TC.pdf. Acesso em: 31 dez. 2019.

SAVIANI, Dermeval. Da nova LDB ao FUNDEB: por uma outra política educacional. 2ª ed. Campinas: Editora Autores Associados, 2008.

APPENDIX – FOOTNOTE

2. Ministério da Educação e Cultura (MEC).

3. Lei de Diretrizes e Bases (LDB).

4. Conselho Nacional de Educação (CNE).

5. Fórum Permanente de Ensino Religioso (FONAPER).

6. Parâmetros Curriculares Nacionais para o Ensino Religioso (PCNER).

[1] Graduated in pedagogy at FAVI, postgraduate in religious education at FABRA, postgraduate in initial grades at CESAP, postgraduate in early childhood education and initial grades with an emphasis on literacy at UNIVES, in course for a master’s degree in sciences of religions at Faculdade Unidas de Vitória. ORCID: 0000-0002-0830-5736. Currículo Lattes: https://lattes.cnpq.br/0218203925572219.

Submitted: January 23, 2023.

Approved: March 9, 2023.

3 Responses

nice .article thanks

nice article.thanks

Very good!