THEORETICAL ESSAY

GERONE, Lucas Guilherme Teztlaff de [1], NOGAS, Paulo Sergio Macuchen [2]

GERONE, Lucas Guilherme Teztlaff de. NOGAS, Paulo Sergio Macuchen. A statistical analysis of spirituality among health professionals of a Hospital in Curitiba-PR. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 05, Ed. 09, Vol. 01, pp. 72-88. September 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/science-of-religion/statistics-spirituality

SUMMARY

Context: there are still few studies that use quantitative methods on the practice of care among health professionals. Objective: To present a statistical analysis on spirituality, religiosity and health in the practice of care among health professionals. Methods: Quantitative survey classified as descriptive applied with 89 health professionals. Results: The statistical analysis indicated that health professionals believe in the influence of spirituality/religiosity on personal life and in the practice of care for the sick person. Considerations: It is necessary to continue new interacademic research with a diversity of statistical techniques that contribute to the analysis of the influence of spirituality and religiosity in the hospital context, and in the training of health professionals.

Keywords: Spirituality, health professional, care, statistics.

INTRODUCTION

During the history of humanity, the themes spirituality/religiosity and health have been intertwined in the work of health professionals. In recent years, research in the field of health has found that religion is a powerful psychological and social factor that greatly influences people’s health (KOENIG, 2012). According to Moreira-Almeida (2010, p. 18), “spirituality/religiosity has been the object of a growing interest among clinicians and researchers in the health area”. Despite this growing, Gerone (2017, p.16) in a literature review points out that “there are few studies on spirituality and religiosity in the practice of care among health professionals”. Among these studies, it is noted that there is a lack of methodological interdisciplinarity between qualitative and quantitative. On the one hand, in the health area most studies use the quantitative method. Medicine has a historical tradition of quantitative research and has difficulty accepting the qualitative method as a scientific study (TURATO, 2005). Psychology often uses quantitative scales to validate qualitative studies (BRYMAN; CRAMER, 1990), such as studies on religious/spiritual coping[3] (PANZINI, 2004).

On the other hand, in studies of religion science and science, the use of the quantitative method is something unusual. For the most part, the central object of theological studies and religion is abstract, for example, faith, which makes quantification difficult (GERONE, 2017). However, even if faith is not quantified, the artifices of faith, such as religious behavior patterns to health events are studied quantitatively (LEVIN, 2003).

This study points out the result of a quantitative research with the use of statistics on how health professionals view spirituality/religiosity in the practice of hospital care. The results obtained in factor analysis were interpreted qualitatively with the application of the content analysis technique.

1. DEFINITIONS OF THE TERMINOLOGIES: SPIRITUALITY/RELIGIOSITY AND HEALTH

It is not intended to issue a complete and final notion about spirituality/religiosity and health, but a panorama of terms within the area of health and religious is sought.

On the one hand, religiosity is a quality of what is part of religion, understood from its Latin etymology, religare, which means “reconnection” between man and God (DERRIDA, 2000). According to Koenig (2012, p.11), religion is a system of beliefs and practices observed by a group of people who rely on rituals or a set of scriptures and teachings “who recognize, worship, communicate with or approach the Sacred, the Divine, God.”

On the other hand, spirituality is a dynamic existential dimension, cultivated in spirit, which impels the conscious human being in his knowledge and vital choices, and which may (or may not) be related to religion (SOUZA, 2013). For physician Puchalski (2006, pp. 14-15), spirituality is:

each person’s inherent search for the meaning and ultimate purpose of life. This meaning can be found in religion, but it can often be broader than that, including the relationship with a divine figure or with transcendence, relationships with others, as well as the spirituality found in nature, art, and rational thought. All of these factors can influence how sick people and health professionals perceive health and disease and how they interact with each other.

The most used notion of health in the academic environment is the WHO, which understands health as a situation of complete physical, mental and social well-being. For Scliar (2007), this notion seeks to express “a full life”. Therefore, Luz (2013) states that the spiritual dimension has been added to the notion of health, since spirituality/religiosity influences all life — values, behaviors, politics, economy, culture, education — which are directly reflected in the notion of health.

2. METHODOLOGY

The research was conducted with 89 health professionals from the Evangelical University Hospital of Curitiba/PR (HUEC), who responded to the survey from March 21 to June 30, 2014.HUEC was formally asked to sign a consent and approval form for the research. Each participant was also asked to sign a free and informed consent form. The opinion of the approval of the Research Ethics Committee of PUCPR, substantiated in no. 48582, on July 2, 2012, was obtained.

The quantitative survey was used as a quantitative survey, classified as exploratory and descriptive. This is a questionnaire with 35 questions, 11 questions elaborated on a nominal and ordinal scale, 23 questions prepared on a 5-point Likert scale (“I totally disagree” with “totally agree”[4] and “totally false” to “totally true”) and, at the end, an open question.

The 35 questions were divided into five sections: section I – sociobiodemographic data; section II – notions of spirituality/religiosity and the place of these concepts in personal life; section III – relationship between spirituality/religiosity and health; section IV – religious-spiritual coping of the professional; and section V – integration of religiosity and spirituality in patient care. In this last section, question 35, because it is open, allowed health professionals to report their experiences of integrating spirituality/religiosity in the practice of health care. For a better understanding of the reports obtained, the content analysis method is used:

Content analysis is “a set of techniques for analyzing communications aimed at obtaining, through systematic and objective procedures for describing the content of messages, indicators (quantitative or not) that allow the inference of knowledge related to the conditions of production/reception (inferred variables) of these messages” (BARDIN, 2011, p. 47).

The five sections of the questionnaire were elaborated to investigate why and how the integration of spirituality/religiosity occurs in the practice of care for sick people among health professionals and pastoralists. Therefore, each section allows a discussion on the theme of this study.

The questionnaire was elaborated and applied via Qualtrics. According to Nogas (2011), Qualtrics is a platform (software) that allows users to create their questionnaires in a web environment. An important advantage of the online questionnaire is the fact of avoiding paper consumption. We used a web access link that referred to the questionnaire and was sent to the emails of health professionals. Thus, each answer inserted began to automatically feed the database, avoiding the consumption of paper, without the need for later typing, conference, which eliminates the possibility of errors in this process.

The data collected by the Qualtrics Online Questionnaire Management Platform were exported and analyzed in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), a computer program that allows elementary and advanced statistical analyses, such as multivariate methods, quickly, making interpretation convenient for a casual or experienced user (PEREIRA, 2006).

2.1 DATA COLLECTION CRITERIA

As this is an exploratory study, we chose to work with a sample that represented at least 10%[5] of the professionals from each of the classes of health professionals at HUEC. In obtaining the sample calculated with size one and a half (1.5), size two was considered (2).

In the studied professions, the population sample greater than 10% was obtained, so the amount of sample collected and the representative percentage within the total population were pointed out: 2 psychologists represent 20% of the total population; 63 nurses or nursing technicians represent 10% of the total population; 4 social workers represent 66% of the total population; 3 physical therapists represent 75% of the total population; 3 speech therapists represent 100% of the total population; 5 pharmacists represent 20% of the total population; 2 clinical nutritionists represent 33% of the total population; 3 chaplains/pastoralists represent 23% of the total population; 5 physicians hired represent 11% of the total population (resident physicians were not included in the sample, because they are outsourced and HUEC does not have the exact number of these professionals; therefore, the sample focuses on the hired physicians).

It was disconsidering the answer of a professional who pointed out the same alternative in all questions from 13 to 34 and in the open question reported having no interest in answering. Thus, 89 answers were considered valid for the analysis.

3. EXPLORATORY ANALYSIS AND STATISTICAL RESULTS

The analyses are the result of the sample of 89 participants. To identify the question under discussion in the text, the capital letter P and the question number in parentheses are used, according to the sections of the questionnaire — for example: (P10).[6]

The results are presented according to the five sections of the questionnaires. In the first topic, the sociobiodemographic data of health professionals are described, which corresponds to questions 1 to 11. The second topic discusses religious practices, the senses of spirituality/religiosity and religious/spiritual coping for health professionals, which corresponds to questions 12 to 18 and 25 to 27. Finally, the third topic discusses the relationship between spirituality/religiosity and health and its integration into care the sick person, which corresponds to questions 19 to 24 and 28 to 34.

3.1 SOCIOBIODEMOGRAPHIC DATA OF HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

The majority of health professionals, 74, are female (83%). Regarding age, 43 are between 26 and 35 years old (48%), 31 are between 36 and 40 years old or above this (35%) and 15 are 21 to 25 years old (17%) (P02). On education levels, 36 have complete higher education (40%) and 50 postgraduate studies (specialization/master/doctorate) (56%) (P03). Regarding the time of professional activity in the health area, 41 have 0 to 5 years (46%), 21 from 6 to 10 years (23%) and 27 from 11 to 20 years or above (30%) (P06).

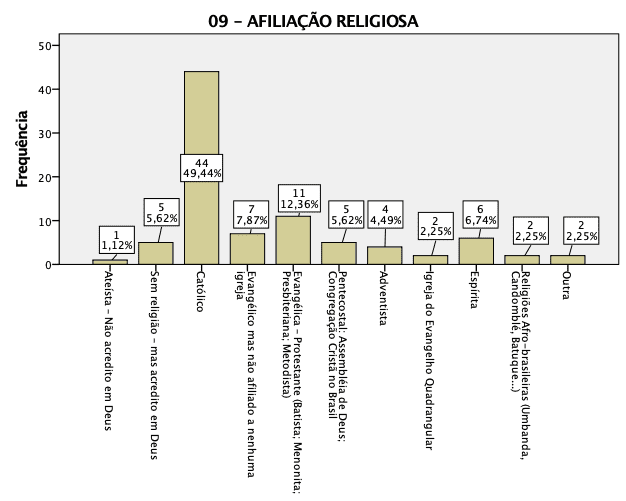

When asking health professionals about their religious affiliation, the answers were as follows:

Graph 1- Religious affiliation of health professionals

3.2 RELIGIOUS PRACTICES, THE SENSES OF SPIRITUALITY/RELIGIOSITY AND RELIGIOUS/SPIRITUAL COPING FOR HEALTH PROFESSIONALS

In view of the results, 76 (85%) of health professionals are Christians: 44 Catholics (49%) and 32 Protestants or evangelicals (36%) (P09). IBGE data for the 2010 Census on religion show that 86.8% of the Brazilian population is composed of Christians, with 64.6% Catholics and 22.2% evangelicals (AZEVEDO, 2012).

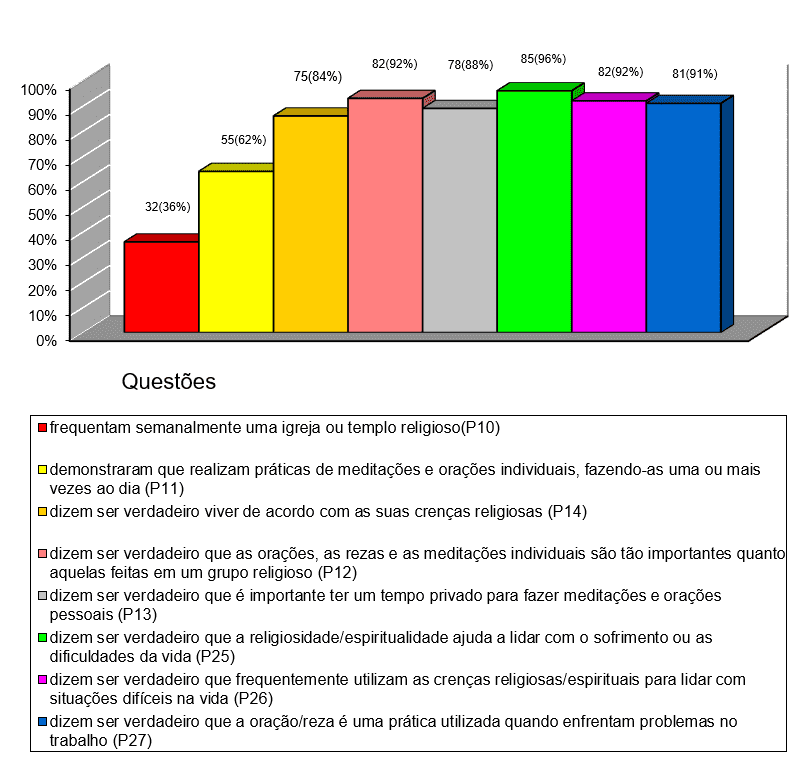

Even though most professionals are Christian on the one hand, few of them attend a church or religious temple weekly. On the other hand, the Christian belief of health professionals may be one of the reasons that some results are above half of the answers or on the rise, since:

Graph 2 – The religious practice of health professionals

The issue of the low frequency of professionals to a church or religious temple with the fact that most of these professionals are Christian and give importance to the belief and religious practices individually, such as the use of coping to face the adverse situations of life, it is considered that health professionals have an individual religiosity. According to Koenig, individual religiosity, also known as non-organizational religiosity:

refers to religious activity that is performed alone and in particular, such as praying, or communicating with God at home, meditating, reading religious scriptures, watching religious television programs, listening to religious radios, or performing private rituals such as lighting candles, wearing religious accessories, and so on (KOENIG, 2012, p. 11).

The notion coined by Koenig about individual or non-organizational religiosity maintains religare with the sacred, with God and religious practices, such as prayers, meditations and others, however, without the need for direct participation or attendance at a church or religious temple. For Teixeira (2005), this “no religion” religiosity is composed of people who are not adept at organizational religion, who prefer to have a religious experience independent of the traditional religious system.

In view of the results presented, it is necessary to relate them to the issue of the integration of spirituality/religiosity in the practice of care the sick person among health professionals, therefore:

a) The fact that health professionals give importance to their spirituality/religiosity favors the understanding that the spirituality/religiosity of the sick person is fundamental for treatment. Just as health professionals understand that their spirituality/religiosity influences the way of coping with adversities in the work environment, they also understand the presence of spirituality/religiosity of people who are sick in treatment.

b) Most professionals being Christian facilitate so the dialogue about the importance of integrating spirituality/religiosity into the care of the sick person. In the Christian religion, the care of the needy or the sick is part of religious belief: “When we saw you sick, or in prison, and went to visit you? And the King will answer unto them, “I say unto you, when ye have done it unto one of these my brethren, even the smallest of mine, you have done it unto me” (Matthew 25:39-40). There is also a practice of integral care of the human being, spirit, soul and body: “And may the same God of peace sanctify you in all; and all your spirit, and soul, and body, be fully preserved irreprehensible for the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ” (1 Thessalonians 5:23).

In this sense, for Christian health professionals, the integration of spirituality/religiosity in the practice of care deals with a testification of their religious values.

3.3 THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN SPIRITUALITY/RELIGIOSITY AND HEALTH AND ITS INTEGRATION INTO CARE THE SICK PERSON

It is observed that there are strong indications of the relationship between spirituality/religiosity and health for huec health professionals: (a) 85 professionals (95%) agree that health problems cause people to turn to religion, so almost all professionals have experienced a situation that, in the midst of health problems, there is a relationship between religiosity and health (P19). About this relationship: (b) 65 professionals (73%) agree that certain religious practices interfere negatively in health treatment (P20), for example, when the patient refuses medical treatment because of his religion. When spirituality/religiosity is well used in medical treatment, almost all health professionals believe that there is a positive relationship between spirituality/religiosity in the treatment of the patient: (a) 84 professionals (94%) agree that the patient’s religiosity (such as prayer, prayer, meditation, attendance to a religious group) cooperates in the treatment (P21); and (b) 84 professionals (94%) agree that the patient’s spirituality has a positive influence on their treatment (P22).

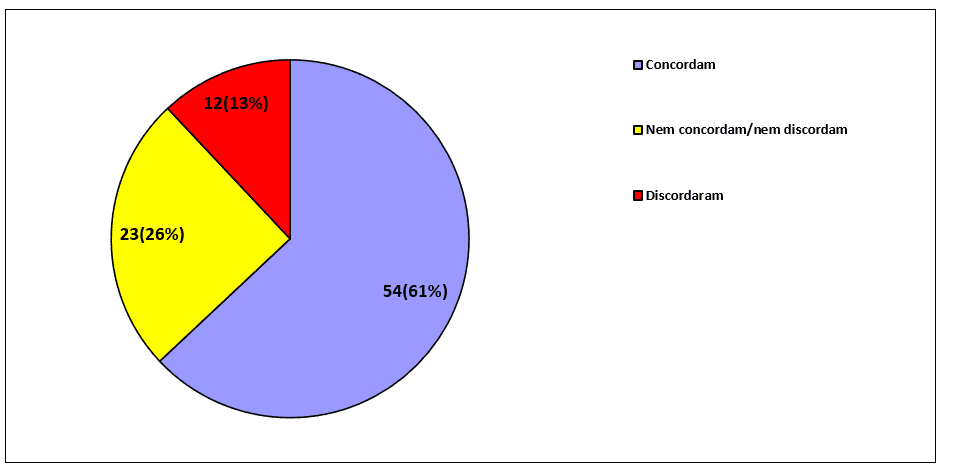

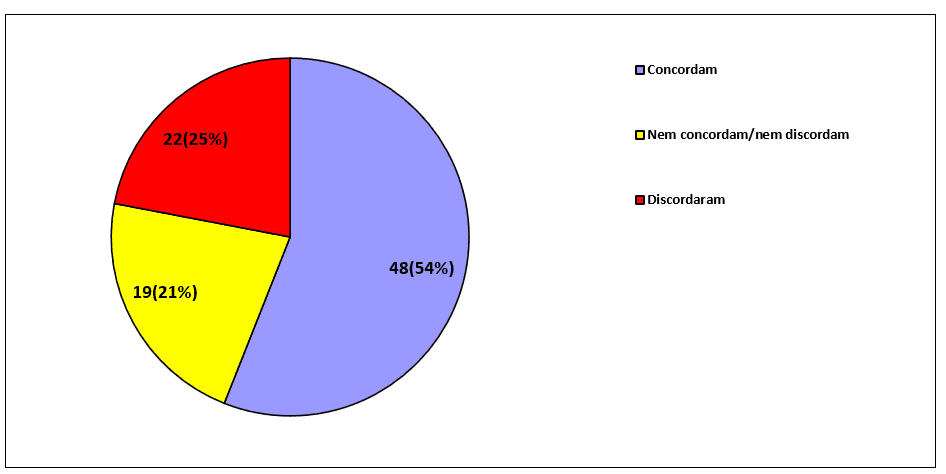

Although health professionals grant high veracity that religious practices and spirituality are positive for treatment, there is no high veracity when addressing the theme of the integration of spirituality/religiosity in treatment directly involving the practices of health professionals. When asking (P29) to the 89 professionals whether the sick people would like to bring the religious/spiritual question to treatment, the percentage of agreement approaches two-thirds of the total:

Graph 3 – The religious/spiritual question in treatment

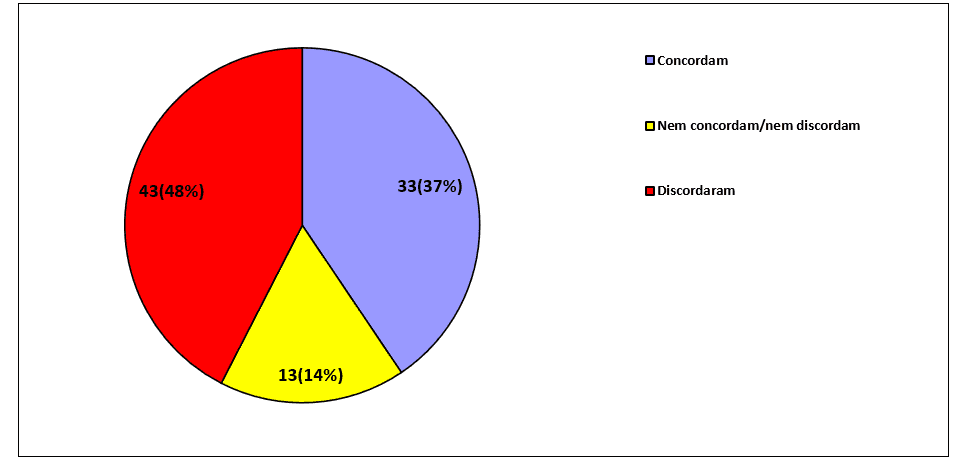

If the 89 professionals often ask sick people about religious or spiritual issues (P30), there is a strong discrepancy in the results – few neutral respondents, between the dissenting and the concordant, together represent 85% of the total respondents, as noted in the chart below:

Figure 4 – Religious issues and sick people

When asking the 89 professionals if they feel comfortable addressing the religious/spiritual issue during the treatment process (P32), the percentage of agreement was predominant, while the percentages of disagreement and neutrality almost tied:

Graph 5 – The approach to spirituality/religiosity in treatment

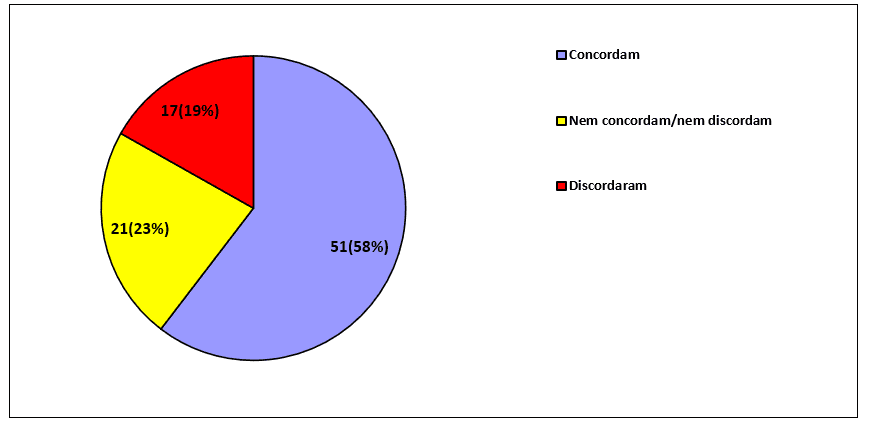

One of the reasons why there is no high percentage of agreement in these questions (P29, P30 and P32) that directly involve the practices of professionals in the integration of spirituality/religiosity in the treatment of sick people is associated with a lack of formation in relation to spirituality/religiosity. Among 89 health professionals, most agree that they should receive training on how to approach the religious/spiritual issue of the patient during treatment (P31):

Graph 6 – Training on spirituality/religiosity

Considerations

It can be insated that the statistical quantitative techniques applied in this study do not claim to replace qualitative analyses. There was a strong complementarity between quantitative and qualitative analysis – quantitative analysis confirmed qualitative analysis, which makes us understand that there is a significant contribution to the area of study of religion. According to Gerone (2015) most studies on spirituality and health do not use quantitative techniques, so that the present work can be considered an innovation in the exploration of the theme, both in the discovery of data and in the possibility of new research involving qualitative and quantitative methods.

These different approaches can provide a broad view of spirituality and health, on the one hand, the quantitative method analyzes and extracts from phenomena the essential part of the research problem and solidifies it in context, for example, the sociobiodemographic issues of the research subjects are essential for the study of the phenomenon. On the other hand, the qualitative method has an extraordinary rich interpretative language of the research problem, such as the behavior or perception of the research subjects.

Specifically the phenomenon of this study: spirituality/religiosity cannot be quantified, however, patterns of behaviors and beliefs of health professionals can be statistically analyzed about the influence of religious and spiritual phenomena on health-related events. In this context, it is considered that the statistical analysis of this study allows:

a) To measure and present the results more accurately, through indicators and graphical representations.

b) To give reliability and academic relevance to research, both (a) for health: medicine, nursing, psychology, and (b) for religious area: theology, science of religion.

Secondly, on spirituality/religiosity in the practice of care among health professionals, statistical analysis allowed statistical analysis to be observed in the universe studied:

a) 99% have a religious affiliation, 85% of which are Christian health professionals. Possibly, therefore, spirituality is a notion that occurs within religiosity through religious practices, such as prayer, which appears in the use of coping to face the adverse situations of life and in the work environment. Spiritual religious coping is a positive resource for coping and resilience, which confirms that health professionals see religiosity/spirituality as something more positive than negative.

b) 94% agree that health problems cause people to turn to religion, having a relationship between religiosity and health. Furthermore, 93% of health professionals agree that the patient’s spirituality has a positive influence on their treatment. Questions about the positive impact of spirituality/religiosity on the treatment of the sick person are extremely relevant. The most relevant question refers to the positive effect of religiosity (prayer, meditation and attendance to a religious group) on the treatment of the sick person. Within this context, it can be inferable that, for health professionals, the spirituality of the sick person occurs through religious practices: prayer, meditation and attendance to a religious group.

c) The results show a remarkable relationship and importance of spirituality/religiosity in the health context, however, statistical indexes fall to 60% when asking health professionals to feel comfortable addressing the religious/spiritual issue during the treatment process. The lack of comfort in dealing with the spiritual issues of the sick person may be related to the lack of knowledge about the spiritual and religious dimensions of the patient. In this, 65% of health professionals agree that they should receive training on how to approach the religious/spiritual issue of the patient during treatment. Training and knowledge about religiosity/spirituality can help health professionals recognize the spiritual and religious need of the sick person and identify whether they would like to bring it to treatment.

Finally, in view of what is observed, it is understood that further research in the areas of religion and health with quantitative and qualitative methods on: the positive and negative influence of the affiliation and religious belief of health professionals in the practice of care is necessary to the sick person and in personal life; the influence of prayer, meditation and frequency to a religious group in the treatment of the sick person, and how spirituality can contribute to the formation of health professionals.

REFERENCES

AZEVEDO, R. “O IBGE e a religião – Cristãos são 86,8% do Brasil; católicos caem para 64,6%; evangélicos já são 22,2%”. Disponível em: <http://veja.abril.com.br/blog/reinaldo/geral/o-ibge-e-a-religiao-%E2%80%93-cristaos-sao-868-do-brasil-catolicos-caem-para-646-evangelicos-ja-sao-222/>. Acesso em 29 de julho de 2014.

BARDIN, L. Análise de conteúdo. São Paulo: Edições 70, 2011.

BÍBLIA DE JERUSALÉM. São Paulo: Paulus, 2002.

BRYMAN, A.; CRAMER. D.Análise de dados em Ciências Sociais:Introdução às técnicas utilizando o SPSS. Oeiras: Celta, 1990.

DAMASIO, Bruno Figueiredo. “Uso da análise fatorial exploratória em psicologia”. Aval. Psicol., Itatiba, v. 11, n. 2, 2012. Disponível em <http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1677-04712012000200007&lng=pt&nrm=iso>. Acesso em 23 de setembro de 2014.

DERRIDA, Jacques; VATTIMO, Gianni (orgs.). A religião: o seminário de Capri. São Paulo: Estação Liberdade, 2000.

ESPINOZA, F. da S.; HIRANO, A. S. “Como dimensões de avaliação dos atributos importantes na compra de condicionadores de ar: um estudo aplicado”. Rev. Adm. Contemp., Curitiba, v. 7, n. 4, 2003. Disponível em <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1415-65552003000400006&lng=en&nrm=iso>. Acesso em 23 de setembro de 2014.

GERONE, L. A Espiritualidade/religiosidade na prática do cuidado entre os Profissionais da Saúde.Rev. Inteirações Cultura E Comunidade, Belo Horizonte, V.11 N.20, P. 129-151, Jul./Dez. 2016.

GERONE, Lucas Guilherme Teztlaff de. Um olhar sobre a Espiritualidade/religiosidade na Prática do Cuidado entre profissionais de saúde e pastoralistas.Dissertação (Mestrado em Teologia) – Escola de Educação e Humanidades. PontifíciaUniversidadeCatólica do Paraná. Curitiba, 2015.

GEORGE, D.; MALLERY, P. SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference. 11.0 update. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

HAIR JR., J. H.; BABIN, B.; MONEY, A. H.; et all. Fundamentos de métodos de pesquisa em administração. Porto Alegre: Bookman, 2005.

KOENIG, H. Medicina, religião e saúde: o encontro da ciência e da espiritualidade. Porto Alegre: LMP, 2012.

LEVIN, J. Deus, fé e saúde – explorando a conexão espiritualidade-cura. São Paulo: Cultrix, 2003.

LUZ, M. Origem etimológica do termo. Diponivel em: <http://www.epsjv.fiocruz.br/dicionario/verbetes/sau.html>. Acesso em 1o de outubro de 2013.

MOREIRA-ALMEIDA A, et al. “Envolvimento religioso e fatores sociodemográficos: resultados de um levantamento nacional no Brasil”. Revista de Psiquiatria Clínica v. 37, n. 1, 2010. Disponível em: <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S0101-60832010000100003&script=sci_arttext>. Acesso em 29 de setembro de 2013.

PANZINI, R. Escala de coping religioso-espiritual (escala cre). Dissertação de Mestrado em Psicologia. Porto Alegre: Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, 2004.

PEREIRA, A. Guia prático de utilização do SPSS: Análise de dados para Ciências Sociais e Psicologia. Lisboa: Sílabo, 2006.

PUCHALSKI, C. M. “Espiritualidade e medicina: os currículos na educação médica”. JournalofEducation Câncer: O Jornal Oficial da Associação Americana para a Educação do Câncer, 21 (1), pp. 14-18, 2006.

SCLIAR, M. “Histórico do conceito de saúde”. PHYSIS: Rev. Saúde Coletiva, Rio de Janeiro, n. 17, v. 1, pp. 29-41, 2007.

SOUZA, W. “A espiritualidade como fonte sistêmica na Bioética”. Rev. PistisPrax., Teol. Pastor., Curitiba, v. 5, n. 1, pp. 91-121, jan./jun. 2013.

TEIXEIRA, F. “O potencial libertador da espiritualidade e da experiência religiosa”. In: AMATUZZI, M. M. Psicologia e espiritualidade. São Paulo: Paulus, 2005.

TURATO, Egberto Ribeiro. “Métodos qualitativos e quantitativos na área da saúde: definições, diferenças e seus objetos de pesquisa”.Rev.Saúde Pública, São Paulo, v. 39, n.3, jun. 2005.Disponível em: <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0034-89102005000300025&lng=en&nrm=iso>.Acesso em 27 de novembro de 2014.

APPENDIX – FOOTNOTE REFERENCES

3. Coping is a word derived from English that does not have a literal translation into Portuguese, which can mean “dealing with”, “handling”, “facing” or “adapting to” (PANZINI, 2004, p. 20).

4. It is difficult to interpret some questions with the alternatives of “agreement / disagreement”; in this case, it should be in terms of “totally false / totally true”, since the terms “agreement / disagreement” can give rise to the interpretation of another type of question, which could be “agree to ask”.

5. The sample used in this study is small, something that limits the results and analysis to the studied group, that is, it does not allow extrapolation or generalization.

6. You can view the entire questionnaire available: http://www.biblioteca.pucpr.br/tede/tde_busca/arquivo.php?codArquivo=3116

[1] Master in Theology from PUCPR. He has a specialization in Organizational Behavior; Specialization in Neuropsychopedagogy; Specialization in Philosophy and Sociology; Specialization in Teaching higher education. MBAs in Administration and Management with emphasis on spirituality and religiosity in companies. Graduated in Commercial Management. Bachelor of Theology. He holds a Degree in Philosophy and a Degree in Pedagogy.

[2] PhD in Administration – PPAD-PUCPR (2010), Master in Technology – PPGTE-UTFPR (2004), Specialist in Higher Education Methodology (1998), Graduated in Mathematics – PUCPR (1994).

Submitted: August, 2020.

Approved: September, 2020.