REVIEW ARTICLE

DIAS, Adailton Di Lauro [1]

DIAS, Adailton Di Lauro. The use of games for teaching English as a second language. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 04, Ed. 07, Vol. 03, pp. 69-76. July 2019. ISSN:2448-0959

ABSTRACT

Assessing the current teaching practices and even observing historically methodological aspects, the students nowadays face an extreme difficulty to develop the cognitive skills and to acquire knowledge in the current educational system. Maybe this is not due to the ineffectiveness of the methods, but the dynamics of relations between the student and the environment. Different age groups require different approaches, which have changed to the condition of obsolescence; they lose their effectiveness significantly, as the time passes. Thus, the games in terms of age and subjects can be an efficient way to display contents due to their universality. The present article aims to explain the reasons why the games constitute an important tool in education and to indicate some ways of applying these tools in the teaching and learning process of English as a second language.

Keywords: Game, ability, language, emotions, learning process.

INTRODUCTION

Considering the technological progress at a constant rate and, even more, observing that the methodologies should accompany these changes with the purpose of constant improvement, this article seeks to relate the use of games to the practice of teaching English as a second language. The study is not restricted to a specific model of the game, but to any playful way of simulating the reality. Thus, the analysis details some types of games and its historical aspects noting the close relation between them, the context, and the learning process. The current proposal may converge to a creation of practices, which use games to make the act of learning enjoyable for the students; it can also help them use the proposed content fluently and efficiently in their daily lives.

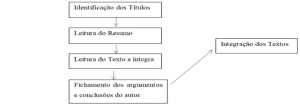

The lack of real situations that contribute to the practice of new language by students constitutes one of the major difficulties to the English teaching process. In the environment of the classroom, different activities can meet part of this gap if the teacher develops student interest in learning, concentrating on the expositive classes and activities. When considering the many possibilities in an environment where the students can simulate extracurricular situations and enter the context of these situations, a better result can be obtained. The prospects for conceptual order in this study consider the literature indicated, but mainly, considers the author’s experience in pedagogical praxis, mainly in teaching English as a second language. Therefore, the author’s view and observation substitute, in this study, the usual required field research.

Based on researches of games for children, games and other concepts and related subjects, there are different ways of application of this study in the pedagogical sphere. For Dantas (1998) “the term ludic refers to the act of playing (in a free and individual way) and play (with regard to a social conduct that involves rules).” However, the specific and dynamic relationship between the method and the students make necessary the deepening and the direction of the games for each subject. According to ANTUNES (2003), to make the games appliable for the practice of effective teaching it is required analysis and research, as the result can be reversed if there is no compatibility between them and the object of learning. The used literature guides part of the concepts construction without defining the applicability of the games. Thus, the author is who suggests such practical use and its possible methodological convergence.

1. SOME CONSIDERATIONS ON THE STEPS FOR LEARNING

An important point to be considered is the context and the conditions, which are applied to the mechanisms of learning. With regard to the games, the audience is very heterogeneous, given the variety of existing games and unlimited range related to the students’ ages. The game is a spontaneous activity, performed by one or more people and, differently of art and work, can be considered as a mean of physical or mental stimulation, sometimes both. The existence of the games dates back to prehistoric times and covers all experience levels, genders and ages. Among the stages of learning, it is important to understand that obstacles to survival are the justification for the different processes. Thus, these processes occur on a scale of increasing complexity. The creation of operations needed to overcome these hindering, it goes through different and well-defined phases, from childhood to adolescence.

The first stage begins at birth and usually lasts until the beginning of language acquisition (until around eighteen months old). During this period, the formation of motor skills and sensory perception begin. The second stage occurs approximately between two and four years old and is defined by the formation of symbolic thought. The use of dolls, cars and other objects of symbolic nature that simulate the reality, constitute part of that particular stage. Between four and eight years old the third stage appears, where the intuitive thought starts to be formed and the objects around become the reference points.

Automatically, this intuition leads to the fourth stage, which is the stage where humans learn to organize concrete operations to associate any object referenced to its meaning. The fourth phase lasts between four to eight years old. The last stage is completed during adolescence, where the construction of mental operations is sufficient for analytical thinking. Taking these steps and their distinctions, it is possible to understand that the appropriateness of games for different age groups can meet most of their members.

2. USING THE GAMES AS A SUPPORT FOR TEACHING ENGLISH

For WITTGENSTEIN (2001), the concept of “game” cannot be restricted to a single definition, but as a multiplicity of settings to establish a relation of family resemblance among them. The definition of multiplicity of Wittgenstein finds support also in CALLOIS (1957), which gives some necessary characteristics for an activity to be defined as a game. The conditions are that the activity needs to be fun, limited in time and place, of unpredictable outcome and that is not productive. Moreover, the activity must have different rules of everyday life and must be fictitious, accompanied by the consciousness of a different reality. The games must therefore approach the real to the imaginary and to the classroom, or the alternative space chosen must be suitable environment to these practices.

The use of repetition in the language levels, when teaching English, should occur as the teaching process of the mother tongue, even for beginner adults. Except for learning grammar, the technique of learning English with the index finger pointing to pictures or objects is very efficient. The teacher must perform the presentation of the language clearly and in games, you should avoid activities that lead to boredom or distraction. At first, tasks such as translation and grammar have very little real merit, since the written language is secondary at this point. The main objective is to link the language to the context and to the real, abstract or fictional environment of games.

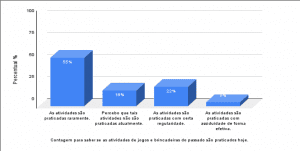

The choice of games should be guided by the applicability to the age group in question, technical feasibility and condition of monitoring by the teacher at all stages of activity. So, constructionist or instructionist educational games can be used since they meet the requirements above. According to the purpose, either type of game can be used depending on various conditions, but it is important to capture the interest of the whole community involved. The following are some types of defined game which may be used:

2.1 INTERACTIVE AND INTERCHANGING GAMES

These games are used to join the member of a group. They help the participants memorize specific information and promote a relaxed atmosphere. The players get distracted, wormed, release tensions and overcame personal reserves. They must be used in the first phases of the developing of a group, when beginning a meeting, after a break and every time the group seems to start getting tired, bored or not motivated.

Music and dance are recommended in active games to tune the group into the proposed activity. The ideal decision is to use short games with a lot of action and a high spent of energy.

2.2 GAMES OF TOUCH AND TRUST

These games help the participants to watch themselves dealing with the trust and confidence in their lives. According to the culture organization and level of opening of people, the group can go gradually to other exercises that involve touch. The games of touch and trust must be used with a lot of care; the instructor must be attentive to the moment and to the reactions of the group as well as the participants, offering them resources to deal well with strong internal psychological processes.

2.3 GAMES OF CREATIVITY AND REFLECTION

These are games that stimulate imaginary expression, intuition and creativity. In these games, the participants can notice themselves and show wide openly to others what they have discovered about themselves, about the subject studied and about the group. The players get in touch with their inside and other players’ inside, noticing what is more relevant in all levels. This kind of game must be used when the groups are completely integrated, working together and using all conditions to go deeply into the subject studied until that moment.

2.4 GAMES OF MANAGEMENT

These games concentrate the players’ attention on planning, managing resources, simulating situations and learning specific techniques. This kind of game must be used after the group is well integrated so that they can get to the proposed aim. Sometimes it is common to appear some difficulties in learning the subject so it is very important that all the living learning cycle is being worked completely.

2.5 CLOSING GAMES

These games help people to have the chance of setting their position related to a subject, to the group and to themselves, transferring what they have got during the learning process to their everyday lives. The synthesizing and ending games are those, which ritualize, evaluate and formalize what has been done during the work. It is really important to make it clear, to each participant, that a cycle is being finished and another is getting started.

2.6 GAMES OF SKILL AND STRATEGY

Can be used in any step of the process or situations. It is important to highlight that sports are included in almost all modalities explained above, but it must be used in order to involve the group over the aspect of learning, but without abandoning the competitive aspect, which is precisely what attracts the public of most age groups. The game, held as an activity for pleasure, constitutes itself as a tool to be studied and applied to English teaching mainly because it is known that our brains learn through a process of repetition, trial and speed (VILLA & SANTANDER, 2003). The trial, or experimentation, is the analysis of the situation. The repetition gives the practice that leads to the speed, or efficiency and effectiveness. The ability of each student will point what level of play should be used.

Understanding, therefore, the different definitions of games and the question of principles of learning from humans, it becomes clear the condition of full use of them in teaching practices. The student interest in learning gets linked to his interest in the proposed game at the time. The environment created by the game, taking also into account that the emotions that influence human beings also promote assimilation, can supply the lack of real situations. Thus, the higher the excitement caused in the games, the greater the possibility of setting the proposed content.

Positive emotions promote more learning (SISTO & MARTINELLI, 2006), so the feeling of joy overcomes the sadness or pain. The teacher, meanwhile, starts to act as mediator between the real and the imagination represented by the game and its outcome. The classroom shifts from one place of pedagogic discourse to a laboratory for sharing experiences, full of possibilities.

CONCLUSION

This study attempted to provide an alternative to the English teaching process as a second language, through games, seeking to aggregate values to the current educational context. Teaching a language, out of its natural environment, is a process that requires skill and creativity by the professional involved. Then, from the moment of choosing the games to the analysis of the results, the teacher should take care to monitor the developments of the students’ acknowledgement, in order not to lose the real goal. The focus is to not only develop strategies, but also make them work properly.

Certainly, the matter does not end. The constant study and the sharing of experiences continue to be the responsibility of the individuals involved in the teaching and learning process. The greater or lesser use and dissemination of the proceedings where the suggested practices are used will determine the success of them. Considering the education space as something to be improved and, according to its dynamism, cannot hold the static and obsolete concepts.

REFERENCES

ABERASTURY, A. A criança e seus jogos. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas, 1992.

AFFONSO, R. M. Ludodiagnóstico. São Paulo: Plêiade, 1995.

AGUIAR, J. S. Jogos para o ensino de conceitos: leitura e escrita na pré-escola. Campinas: Papirus, 1998.

ANTUNES, C. Jogos para a estimulação das múltiplas inteligências. 12ª edição. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes, 2003.

CALLOIS, Roger. Les Jeux et les hommes. Paris: Gallimard, 1957.

DANTAS, H. Brincar e Trabalhar. In: KISHIMOTO, T. M. (org). Brincar e suas teorias. São Paulo: Pioneira, 1998.

SISTO, F. F. & MARTINELLI, S. de C. (orgs.) Afetividade e dificuldades de aprendizagem: uma abordagem psicoeducacional. São Paulo: Vetor, 2006.

VILA, Magda & SANTANDER, Marli. Jogos cooperativos no processo de aprendizagem acelerada. São Paulo: Qualitymark, 2003

WITTGENSTEIN, Philosophical Investigations, Blackwell Publishing Ltd., MA: 2001.

[1]Specialist in English by FIJ-Integrated Colleges of Jacarepagua, Rio de Janeiro (2007). Majored in Literature by the University of State of Bahia, Brazil. English and Portuguese Teacher at IFRR-Brazil.

Submitted: June, 2019..

Aprovate: July, 2019.