ORIGINAL ARTICLE

SANTOS, Maria Eliane Ferreira dos[1] , MEDEIROS, Késia Girlane Santos de[2]

SANTOS, Maria Eliane Ferreira dos. MEDEIROS, Késia Girlane Santos de. Education for the inprisons: Challenges and perspectives. Multidisciplinary Core scientific journal of knowledge. Year 05, Ed. 10, Vol. 20, pp. 144-160. October 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/education/education-for-the-inprisons, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/education/education-for-the-inprisons

SUMMARY

The present work aims to present the obstacles that arise in the educational process in prisons, given the lack of adequate public policies to invest in a quality education for students deprived of liberty. Through the readings carried out it is possible to realize that there has been a chance on the part of the rulers and society for a long time. From the 20th century on, some investments have gradually come up, but we still come across a devalued education, by the rulers and by society. The purpose is to demonstrate that despite the obstacles, it is possible to rescue the history of the inprison and lead him to build a family and return to live in society with dignity. Prison education is a great challenge, but the possibilities are known and even in the face of obstacles we have faced positive results from students who seek knowledge, build knowledge and have an indisputable intelligence. “Prison education” is an important guarantee of a new beginning for a resocialization, because through the classroom it is possible to guarantee students deprived of freedom, dignity, given the spaces of which they are part is of total contempt for life, in the classroom, the imprisoned feel like people again, feel able to face the challenges of life and even resume a healthy life in society. It is worth noting that a good quality education in prisons, avoids rebellions and there is a reduction of penalty for those who attend school. That’s because the Criminal Enforcement Act states that 12 hours of school attendance equateto one day less than time. Education is a right that must be guaranteed to all, as ensures the Law of Guidelines and Bases of National Education, in Article 205, which declares access to education as a right of all, so as to be promoted and encouraged by society, prioritizing the development and preparation of an individual in society, therefore, refers to the student deprived of liberty.

Keywords: Obstacles, society, resocialization, freedom.

1. INTRODUCTION

This research aims to present the great dilemma of prison education in Brazil, obstacles that until then, it is not yet possible to find an appropriate solution, given the lack of an adequate public policy for teaching in prisons, because it is presented in the modality of Youth and Adult Education (EJA). It is believed that therefore, so many obstacles are faced by students deprived of liberty.

According to Novo (2019), man was born to be free, it is not part of his nature to remain caged. Even if the school is a refuge, it is still possible to come across students who claim safely, there is no interest in the classroom, but often, he seeks this space to escape punishments, that is, prison is seen as a place that punishes, persecutes, mistreats, humiliates, and the prisoner for not enduring so many humiliations to see in school a place of comfort and security.

Also according to Foucault (1987), prison is based on “deprivation of liberty”, emphasizing that this freedom is a good present to all in the same way, that is, losing it, means losing the right to come, and shows mainly that the fact of not being free, therefore, will suffer the consequences related to the infractional acts committed by prisoners.

2. METHODOLOGY

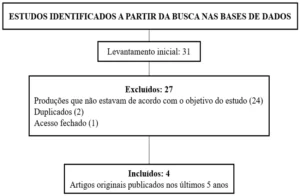

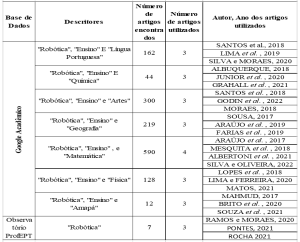

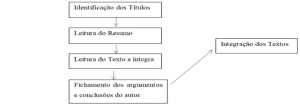

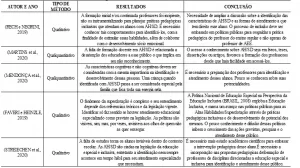

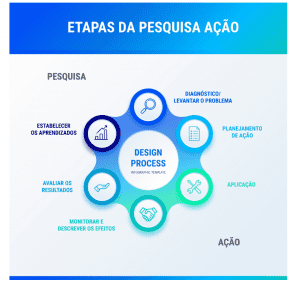

This article was elaborated from a bibliographical research of various aspects and authors who were willing to talk about the confrontation of prison education, this research, carried out through the Internet, exhaustive reading in various sources, in the incessant search to understand the challenges of the EJA in the prison context, and seek in a clear and objective way, in order to understand a little of the historical context and the purpose of prison education.

The analysis of this research and the information presented here, arise according to the understanding of the readings performed, that is, it is these readings that bring a range of possibilities to better understand the confrontation of prison education, especially with regard to teachers who are part of this process.

3. DEVELOPMENT

3.1 PRISON EDUCATION: A CONSTANT CHALLENGE

To understand the history of prison education, it is important to know the historical context of the Brazilian prison system, which over time has undergone major changes, always seeking to understand the comings and goings of the incardo. It is not possible to talk about prison education without first knowing the main facts that have been modified over time.

In the colonial period, Brazil was governed by the “Ordination”, of “Portugal. Thus, the Philippine Code was a very relevant milestone at this time, which abolished the last Ordination (Manuelines). This Code was considered by history as legislation unrelated to human rights, because it entailed cruel, degrading and vile penalties, with an aspect of corporal revenge (SCHICHOR, 1993).

This code portrays a social inequality with regard to the less favored, given the fact that the rich suffer softer sentences. A classic example of the execution of these sentences is the death sentence of Tiradentes which shows cruelty and the odour to the humanization of the penalty:

Therefore they condemn the Defendant Joaquim José da Silva Xavier by nickname the Tiradentes Alferes who was the paid troop of the Captaincy of Mines to which with bare and trading floor is led through the public streets to the place of the gallows and in it die natural death forever, and that after death is cut off his head and taken to Villa Rica where in a more public place of it will be nailed , on a high pole until time consumes it, and his body will be divided into four quarters, and nailed to poles along the path of Minas on the site of Varginha and Sebolasa, where the Defendant had his infamous practices and the most in the sites of larger settlements until time also consumes them; declare the Defendant infamous, and his children and grandchildren having them, and their assets apply to the Tax And Royal Chamber, and the house in which he lived in Villa Rica will be razed and salted, so that never again on the ground is built and not being proper will be evaluated and paid to its owner for the confiscated goods and on the same floor will rise a pattern by which the infamy of this abominable Defendant is kept in memory. (apud DOTTI, 2003, p. 27)

The laws of Brazil were only developed with the Constitution of the Empire in 1824. Like this.: “[…] in 1824, the first constitution was granted. This brought guarantees to public freedom and individual rights. The new legal law provided for the need for a criminal code, which should have pillars based on justice and equity” (TAKADA, 2010, p. 3). That is, it is perceived that the laws were always present in society, however they were made as a form of repression, of distancing the individual unable to live in society.

Thus, the Criminal Code of the Empire began to act legally with a more human aspect, adhering as a penalty the deprivation of liberty.

Later, with the introduction of a republican system, a new Code was created, from 1890 with softer sentences compared to those of the Criminal Code of the Empire. However, still, there is a point of repression and social segregation has always existed in Brazil.

It is understood in this context that until then the so-called “Education” was not yet something provided for in the law, the whole historical context is formed by a distancing of this individual from society, since there are still no laws that address the issue of resocialization and of schools functioning in so-called “jails” and/ or prisons. One cannot talk about prison education, without first addressing the various issues of the system itself, such as the laws that governed the country, given the changes that over time have been improved to enable the private of liberty to attend a classroom.

Education in the prison system began in the 1950s. Even in the early 19th century, the prison was seen as just a place of containment of people, without any proposal to requalify prisoners.[3] According to studies conducted there was no education that covered the deprived of liberty, this in turn was at the mercy of all kinds of violence, there was no public policy that benefited the prisoner, life had no value.

However, with the development of treatment programs within prisons, this proposal arose. Previously, there was no form of work, religious or secular teaching.

Therefore, in the early 1950s, the failure of this prison system was identified, which consequently motivated the search for new directions, thus inserting school education in prisons. Foucault (1987, p. 224) says: “The education of the inmate is, on the part of the public authorities, at the same time an indispensable precaution in the interest of society and an obligation to the inmate, it is the great force of thinking”.

In the 20th century it was noticed that the prison population, due to social segregation, which is evident in Brazil, did not have much education or reached a high standard with regard to formal education. Thus, around 1950, there was the incorporation of education in the penitentiary system.

A new conception of the prison system begins, with regard to prison, only from these changes in Brazil, in the mid-1950s, the General Norms of the Penitentiary Regime (Law No. 3274/57) were edited and accepted as the one that inaugurated the integral educational conception for the prison population (VASQUEZ, 2008).

3.2 PRISON EDUCATION: HOPE FOR NEW OPPORTUNITIES

Only from the government of Juscelino Kubitschek were these General Norms of the Penitentiary Regime ratified, presenting terms such as “moral education”, “intellectual education”, “physical education”, “artistic education” and “professional education” (VASQUEZ, 2008, p. 70). The main objective would be to improve in the daily life of prison a quality education, which could insert the individual deprived of liberty in an attempt to offer a better living condition for those who are without the right to live in society, but unfortunately it was not well consolidated, for lack of an efficient organization, which demonstrates the national reality of dismay with Brazilian prisons.

Education is a right guaranteed by law, given the possibility of change, of coping with poverty, the attempt to reduce violence and make this prison population have a minimum of dignity, transform their lives, become more human, being able to create in themselves, the hope of conquering new opportunities, and that can from education face society.

It is the basis, that is, one of the main tools for personal growth, through it it is possible to transform, expand the knowledge of the world, especially to lead the deprived of liberty to value life more, and the people who surround it, when they can understand that school is their place of refuge. It is worth noting that it is necessary to invest in a quality educational policy, improving human value, social inclusion, culture and economic.

In relation to school education policies in prisons, its complex character of organization and functioning is emphasized, as they are carried out from the articulation of the education system with the prison system (Ministry of Education, Ministry of Justice, State Departments of Education and Secretariats of Social Defense or Prison Administration, as well as organs that are part of these systems, such as prisons and penitentiary) , which, in turn, is articulated with the criminal justice system and with society. (OLIVEIRA, 2013, p. 957).

In this context, the Federal Constitution of 1988, considered the most democratic and citizen of all Brazilian Constitutions, ensures in its principles, bases focused on the understanding of education in social security systems as a matter of fundamental and social human rights. Therefore, investing in prison schools implies in several aspects, among them, is the possibility of returning this subject to society, for living with family, friends, access to work, the return to the meaning of the word life. However, to speak of prison education, it is necessary to present the laws that govern the institution.

Art. 1º The Federative Republic of Brazil, formed by the indissoluble union of States and Municipalities and the Federal District, constitutes a Democratic State of Law and has as its foundations:

I – sovereignty;

II – citizenship;

III – the dignity of the human person;[…] . (BRASIL, 1988)

In this context, the Law of Criminal Execution – LEP ( Law No. 7,210/84) addresses precisely how to conduct the execution of the sentence in criminal establishments:

Art. 1º The criminal execution aims to effect the provisions of sentence or criminal decision and provide conditions for the harmonious social integration of the condemned and the hospitalized.

[…]

Art. 3º The condemned and the hospitalized will be guaranteed all rights not affected by the sentence or the law. (BRASIL, 1988).

In Articles 10 and 11 of the LEP, it is clearly described that the State has full responsibility to ensure the realization of such rights:

Art. 10. Assistance to the prisoner and the internee is the duty of the State, aiming to prevent crime and guide the return to coexistence in society.

Sole paragraph. The assistance extends to the graduate.

Art. 11. The assistance will be:

I – Material;

II – Health;

III -legal;

IV – Educational;

V – Social;

VI – Religious. (BRAZIL, 1984, our griffin)

Finally, the Federal Constitution of 1988, in Article 6, establishes that:

Art. 6th. Social rights are education, health, work, housing, leisure, security, social security, protection of motherhood and childhood, assistance to the homeless, in the same form of this constitution.

It thus refers to the social right which requires positive assistance from the State.

That whether the individual is in prison or not, nothing deprives him of his rights, such as health and work.

It is worth pointing out that education is also paramount in the prison system, it is the possibility of changes in the life of this individual, it is the rescue of self-esteem, but it is also the awareness of society in understanding that the citizen by losing his freedom, also loses a little of himself.

The possibility of returning this individual to society when he studies is much greater than when he does not seek school. It is there in the classroom that the process of transforming, of growth, improvement and improvement takes place. The prison school may not be the best choice for the deprived of liberty, but it is the moment of refuge, it is the possibility of changes, given, in addition to the construction by knowledge this in turn will have its penalty reduced. The more he dedicates himself to school, the more access to knowledge and the chance to return to family life.

It is worth noting that through all the socio-educational context, the lack of investments in prison education is perceived, because this already comes from long years in the face of difficulties with regard to their existence within prisons, because at the same time that this could be the exit door, for the rulers it is only an unnecessary expense. Society does not willingly see, for her, the prisoner does not have to have “perks”, that is, from the moment the individual commits a crime, needs to assume and pay for it.

However, to people who are within the prison system, whether female or male, have the right to school access, it is highlighted in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, article 26, that everyone has the right to education, aiming at the full development of the individual and the reaffirmation of respect for human rights. (OLIVEIRA, 2013)

It is understood that these rights are given to each and every citizen (a), because the purpose of it is not to punish, but to guarantee the legality of these rights for the deprived of freedoms in order to make them aware of their role in society, especially when living with other people. The prison does not change, but the school has this transformative power, a very important role in the construction of this prisoner’s identity. And it is not something incited by anyone, but there are laws that guarantee access to the school:

The Brazilian prison system is departing from social problems. According to the data recorded in 2017, currently, there are 668,182 prisoners in Brazil, while the number of vacancies is 394,835, resulting in overcrowding with a percentage equivalent to 69.2%. Thus, it demands public policies from the State, aiming at an intervention to make changes.

In the case of the prison system, the benefit lies not only with inmates, but also for society. (VELASCO, 2017)

This right is provided for in several international documents, such as: World Declaration on Education for All (Article 1); International Convention on the Rights of the Child (paragraph 1, art. 29); Convention against Discrimination in Education (Articles 3, 4 and 5); Declaration and Action Plan of Vienna (part 1, paragraph 33 and 80); Agenda 21 (chapter 36); Copenhagen Declaration (compromise no. 6); Beijing Platform for Action (paragraphs 69, 80, 81 and 82); Aman’s statement and the United Nations Decade of Action for Education in the Sphere of Human Rights (paragraph 2). (PRADO, 2017)

The challenges faced are great, but possible to face them, the law guarantees access, equal treatment for all, regardless of their freedom or not. Education is a right of every citizen, it is through it the possible conquest, however, it is known that investments are increasingly scarce, there are no adequate public policies to prevent this unbridled growth of social inequalities, which makes the prisoner at the mercy of exclusion, the lack of family affection, and this individual increasingly needy and prone to return to the world of crime.

The school is your place of refuge, it is the search for the rescue of identity, the will to win away from crime, it is worth mentioning that prison is already a process of discrimination, exclusion, the school is seen as a place of conquest. It is in this sense that this study seeks to investigate how the implementation of public policies for the education of young people and adults (EJA) in a situation of deprivation of liberty, how this insertion occurs, and what has actually made this space more attractive for this individual. (NASCIMENTO, 2013)

In turn, other questions arise, does the inmate go to school only for remição, or does this seek to improve their knowledge? What is the purpose of a detainant facing the classroom? The questions are the most diverse, however it is worth mentioning that [i] living with this reality brings other questions, such as: is it possible to be accepted by society? Is it possible to get a job so you don’t go back to the same offenses? For some of these questions we have very hard answers, for some not.

The Right to Education is guaranteed to persons imprisoned by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948); in the Brazilian legal system by the Federal Constitution (1988), the Law of Guidelines and Bases of Education (1996) and the Criminal Execution Law (1984). (SILVA, 2013).

The educational level of people entering the prison system is usually very low, and this causes great difficulties in the labor market, in this case more investment was needed, that is, a well-designed and well-managed public policy to invest heavily in education. When reflecting on the situation of the prisoner in Brazil, it is observed that most prisoners did not have the best opportunities with regard to education, did not study, did not give the right to come and go of the prisoner, the permission to visit family was almost non-existent, (BRASIL ESCOLA, 2017).

It is noteworthy that in view of so many unsuccessful attacks regarding the inclusion of individuals imprisoned back to social relations and the valorization of prison education, it is observed that the model, in this educational way in Brazil, is located in the State of São Paulo. Tavolaro (1999), reports that at first there was no participation of society. According to the historical context of prisoner education in the State, until 1979, teachers commissioned by the Department of Education taught basic education in prisons, based on school years of official schools, with annual serialization and the use of pedagogical material applied to children. It is perceived that there was no pedagogical practice capable of meeting the needs of the prisoner, only in 1988, when the responsibility for the education of prisoners was conferred by the State Foundation for Support to the Imprisoned Worker – FUNAP, designated the remuneration of monitors, operation of schools and applied teaching methodology.

Behold, several questions arise, what is the purpose of the prisoner being in the classroom? Is there an interest on the part of the rulers and society that it be inserted in a re-education program? According to previous research, it is perceived that this “reeducation” that aims at the state in practice does not exist. For what really draws attention in this aspect is that the greatest concern of the prison system when receiving a condemned individual is not in his re-education, but in his deprivation of liberty. (SANTOS, 2008.).

That is, when entering the prison the individual is already condemned to live a mediocre life, of crumbs, society discards him and forgets that one day he was already part of this process. The family most often also abandons him and he continues to become increasingly involved in the world of crime, there are not enough reasons for a reinsertion, the subject feels despised, unable to re-believe in himself. According to Claude, he says:

Education is valuable because it is the most efficient tool for personal growth. And it assumes the status of human right, because it is an integral part of human dignity and contributes to the importance of knowledge, knowledge and discernment. Moreover, by the type of instrument it constitutes, it is a multi-sided right: social, economic and cultural. Social law because, in the context of the community, it promotes the full development of the human personality. Economic law, because it favors economic self-sufficiency through employment or self-employment. And cultural law, since the international community has guided education to build a universal culture of human rights. In short, education is the prerequisite for the individual to act fully as a human being in modern society. (CLAUDE, 2005).

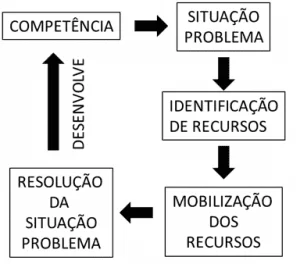

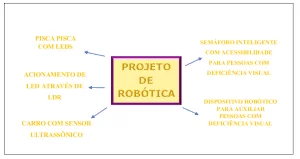

In this context, it can be identified that deprivation of liberty does not contribute to resocialization. Therefore, some realization is needed in this direction, in order to mitigate or even resolve this misunderstanding. For this it is necessary to develop appropriate educational programs for the prison system that can reach prison society in general, so the Education of Youth and Adults aims to literacy and work the construction of the citizenship of the inmate. According to Salla (1999, p.67) “[…] as much as the prison is unable to resocialize, a large number of inmates leave the prison system and abandon marginality because they had the opportunity to study.”

When the prisoner has the opportunity to be inserted in the classroom, there is a surprising change of behavior, he begins to think much more about the family, in the rescue of his own identity, in the search to strengthen family ties, at that moment it is perceived that the EJA is the only port capable of rewriting this story.

3.3 THE IMPORTANCE OF EDUCATION FOR STUDENTS DEPRIVED OF FREEDOM

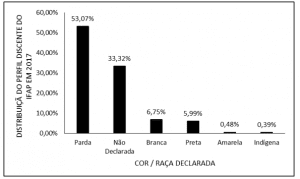

The text in question is not trying to show the situation of Brazilian prisons, but the importance of education within the system, but it is necessary to address issues that are pertinent in order to better understand the situation of the system in general. The most relevant aspect and possible consideration is to observe the profile of the prison population in Brazil, according to data provided by the National Penitentiary Department of the Ministry of Justice, in Brazil, most of the prison mass is composed of young people under thirty years of age and with low schooling, in a considerably frightening number, (97% are illiterate or semi-illiterate). (SANTOS, 2008).

Therefore, crime is linked to the low level of education and both the social economic issue. So that they urgently need to develop educational projects that can work the awareness of the students, in order to lead them to understand the reality and consequently their place in this world. According to Silva (2008), an individual who is born disadvantaged, without any access to an education, is not able to act with discernment in his acts. Gadotti points out that:

The need to work in the re-educating “[..] the antisocial act and the consequences of these acts, legal disorders, personal losses and social stigma”. In other words, developing the ability to reflect on us, making them understand reality so that they can then desire their transformation. (GADOTTI, 1999, p.62).

That is, an education that can be able to assume an intellectual autonomy of students, offers conditions to analyze and understand the human and social prison reality in which they live. The penitentiary system urgently needs an education that has the priority concern of developing the capacity of criticality, capable of involving them in the possibility of alerting them to the choices they need to make throughout their lives, including the period in which they are individuals belonging to their coexistence, the prison.

According to Gadotti (1999), education frees and within prison the word and dialogue, are considered the main key. The only motivation of an inmate is freedom, and freedom is the force of thought

In his analysis Freire (1980), he states that:

Awareness is […] a reality check. The more awareness, the more reality is “unveiled,” the more it penetrates the phenomenic essence of the object, in front of which we find ourselves to analyze it. For this same reason, awareness does not consist of “standing in front of reality” by assuming a falsely intellectual position. Awareness cannot exist outside the “praxis”, or rather without the action-reflection act. This dialectical unity is, in a permanent way, the way to be or to transform the world that characterizes men. (FREIRE, 1980, p. 26).

From the perspective of education, we must work with the prisons fundamental concepts, such as family, love, dignity, freedom, citizenship, misery, community, among others. For this has the function of demystifying a very important reality, that education within the prison system will take the most important step, the true sense of resocialization, the search to overcome the false argument that, once a bandit, a bandit always”.

Education in prisons is provided for in the LEP:

Art. 17. Educational assistance will include school education and professional training of the prisoner and the inmate. Art. 18. The teaching of 1st degree will be mandatory, integrating into the school system of the Federative Unit. Art. 18-A. High school, regular or supplementary, with general education or professional education of high school, will be implemented in prisons, in obedience to the constitutional precept of its universalization. § 1 – The education taught to prisoners and prisoners will integrate into the state and municipal education system and will be maintained, administratively and financially, with the support of the Union, not only with the resources allocated to education, but by the state system of justice or penitentiary administration. § 2 – Education systems will offer prisoners and prisoners supplementary courses in the education of young people and adults. (BRASIL, 1984).

According to research conducted in this perspective of verifying the EJA, it is perceived that its entire structure is based on norms and laws that regulate this modality, given that the private liberty cannot enjoy the right to move to a common school, this in turn not to lose the focus of studies, seeks in prison a way to re-find , and even prepare through studies for a return to society.

Education in the prison system follows the rules of human rights, that is, the fact that the individual is imprisoned does not take away the right or confiscation of studies, this in turn goes in search of remition, and is faced with the realities of the most diverse and begins to realize, that it is much more valuable the search for knowledge, the involvement with the universe of books , than even involvement with a simple document to reduce the penalty.

Scholars such as Foucault began to defend education as a prisoner’s right: “The education of the inmate is, on the part of the public power, at the same time an indispensable precaution in the interest of society and an obligation to the inmate, it is the great force of thought” (FOUCAULT, 1987, p. 224).

That is, it is through education, the first steps towards a new life, to different perspectives with regard to living in society. For this educational modality it is worth noting that each epoch was emerging new ideas, and being improved so that a differentiated and qualitative work was possible. If the prisoner studies, does not seek confusion, is always able to meet the needs of the system, willing to change his life, the search for dignity is an essential milestone in his existence. It is observed that since the colonial period, Paiva (1987) states that this education was reduced to literacy, which aimed at the indoctrination of adult Indians to accept Portuguese domination; this same teaching was directed to the children of the Indians in the teaching of Portuguese language and catechesis.

Even in the Empire, there were no substantial changes in this conception. It is only in the Republic that we find a greater appreciation of this education, because it was linked to the idea of preparing the labor for economic development that the country was underway. This occurs specifically from the “revolution of 1930 that we will find in the country adult education movements of some meaning”. (PAIVA, 1987, p. 165).

When reflecting on the colonial period, it is subdued that education for those who lost their right to come and go was already devalued, that is, since the individual gave up the conviviality in society he should pay for his crime and live in a degrading way, only then in the Republic begins a new stage, a keener look at the offer of an equal education for all.

By removing the right to come and go of a person, incarcerated them, he is taken from the right of coexistence in society, keeping him in a space that was planned to prevent him from living away from the rest of society.

When thinking about education in the prison space, one must reflect on the limits clearly imposed, however, one should not reduce the educational process, because like any other space, one must think and understand the interests and learning needs of that individual who is reclusive, and what limits and certain situations are imposed on this educational process.

To portray the issue of prison education, it is necessary to deal with a regrettable occurrence, the increasing rate of violence and crime that has recently resulted in a large increase in the prison population, a fact that occurs not only in Brazil, but in Latin America in general.

When talking about the offer of education in the prison context, it is necessary to approach a broader discussion with regard to Youth and Adult Education (EJA), arguing that this modality in a prison environment is specific, that is, its main intention is to reach a marginalized public, but no less provided with the right to access to education. By perceiving the educational centrality, and the possibility of a new opportunity for coexistence and dignity, we understand other essential factors in the life of this citizen, that is, the right to education, health, a work within the system itself, so that he feels part of the process and knows that he is there for disobeying rules imposed by society itself.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 clearly affirms the right of “every person” to “instruction, a right reinforced by the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of 1966, and understood as the “full development of the human personality and the sense of its dignity” and the strengthening of ‘respect for human rights and functional freedoms’ (art. 13).

With regard to the prison population, the united nations minimum rules for treating prisoners (1955) stipulow all prisoners should have the right to participate in cultural and educational activities. Therefore, this principle in Brazil, according to the Criminal Execution Law of 1984, explains in Article 3 that the condemned and the internwill be guaranteed all rights not affected by the sentence or the law. (IRELAND, 2011).

4. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Acting as a teacher of education in prisons is a challenging decision-making, because it is something different, a reality previously unknown, but when being part of the process and getting to know more closely the reality faced by students deprived of freedom, very important facts arise, which make a whole differential in the work of any teacher.

It is perceived that it is not any teacher who is able to give it with this reality, it is necessary a psychological preparation and the certainty that it will come across several situations and needs to face them always with enthusiasm, responsibility and commitment, after all prison education, however much one tries to compare with regular education, will never have this proximity, given, the students come from totally different realities from those experienced by regular students. They have lost their freedom, the right to come and go, they need to reconstruct their stories in a short time and because it is the modality of Youth and Adult Education (EJA), requires a much greater effort on the part of them and teachers.

By allowing an inmate to have access to the classroom, giving him the opportunity to reflect on the social context, because it will lead him to think if there is a possibility of returning to family life, he is tired of living in prison, he himself begins to believe that he is able to change his story and from there begins to value education as an escape to this transformation. Although we do not have specific public policies for prison education, we need to believe in this possibility of transformation, reconstruction and search for an identity, of no longer being considered a simple inmate, but of an individual capable of reconstructing his own history through education.

5. REFERENCES

BRASIL. Lei nº 7.210, de 11 de julho de 1984. Institui a Lei de Execução Penal. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/L7210compilado.htm>. Acesso em: 28 nov. 2019.

BRASIL. Lei de diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional. LDB.9394/96. São Paulo: Saraiva, 1996.

BRASIL, Lei Nº 9.394, 20 dez. 1996. Diretrizes e Bases da Educação Nacional.

CLAUDE, Richard Pierre. ” Civil-Military/Police Relations” . In: Educating for Human Rights: The Philippines and Beyond, pp. 71-101. Manila/Honolulu: Universidade das Filipinas – Universidade do Havaí, 1996. https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1806-64452005000100003. Acesso em: 10 de jul. 2019.

Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil: (1995). Promulgada em 5 de outubro de 1988. 26 Edição atualizada e ampliada. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2007.

DOTTI, René Ariel, Casos criminais célebres. 3.ed., ver. E ampl. São Paulo: Revista dos Tribunais, 2003, 430 p.

DHNET. Diretos Humanos na internet. Comentários ao artigo 13. Disponível em: http://www.dhnet.org.br/direitos/deconu/coment/balestreri.html. Acesso em: 10 de maio. 2019

DHNET. Diretos Humanos na internet. Disponível em: https://www.direitonet.com.br/artigos/exibir/2231/Ressocializacao-atraves-da-educacao. Acesso em 10 de fev. 2019.

FREIRE, P. (1983). Educação e mudança. 7., Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra.

FREIRE, P. A importância do ato de ler. (1983). 3., São Paulo: Cortez.

FREIRE, P. A importância do ato de ler, (1994). Em três artigos que se contemplam. 14. São Paulo; Cortez.

FREIRE, P. Pedagogia do oprimido. (1987). 30., Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra.

FREIRE, P. Pedagogia da Autonomia. (1997). Saberes necessários a prática educativa. São Paulo: Paz e Terra.

FREIRE, P. e RIVIÈRE, P. (1987). O processo educativo segundo Paulo Freire e Pichon Rivière. São Paulo: Vozes.

GADOTTI, M. (1984). A educação contra a educação: o esquecimento da educação e a educação permanente. 3., Rio de Janeiro: Paz e Terra.

GADOTTI, M. História das idéias pedagógicas. (1998). 6., São Paulo: Ática.

GADOTTI, M.; FREIRE, P. e GUIMARÃES, S. (1985). Pedagogia: diálogo e conflito. São Paulo: Cortez – Autores Associados.

FOUCAULT, M. 1987. Vigiar e punir: nascimento da prisão. 20ª ed., Petrópolis, Vozes, 287 p.

FOUCAULT, M. (1979). Microfísica do poder. Trad. de Roberto Machado. Rio de Janeiro: Graa.

FOUCAULT, M. Vigiar e punir: (1998). Nascimento da prisão. Trad. de Raquel Ramalhete. 18., Petrópolis: Vozes.

G1. Raio X do sistema prisional em 2017. 06/01/2017. Disponível em: <http://especiais.g1.globo.com/politica/2017/raio-x-do-sistema-prisional/>. Acesso em: 10 de nov.2019.

HISTÓRIA DA LOUCURA. (2001). São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva. Ciências da cognição. Florianópolis: Insular.

NASCIMENTO, Sandra Maria do, Educação de Jovens e Adultos EJA , na Visão de Paulo Freire.2015. http://repositório.roca.utfpr.edu.br:8080/jspui/bitstream/1/4489/1MD EDUMTE 2014 2 11 6.pdf. Acesso em: 10 de fev. 2019.

NOVO, Benigno Núñez. A relevância da educação prisional como instrumento de ressocialização. Revista Jus Navigandi, ISSN 1518-4862, Teresina, ano 24, n. 5847, 5 jul. 2019. Disponível em: https://jus.com.br/artigos/74918. Acesso em: 11 de out. 2020.

NOVO, Benigno Núñez. A Educação Prisional Que Recupera. Brasil Escola. Disponível em: https://meuartigo.brasilescola.uol.com.br/educacao/a-educacao-prisional-que-recupera.htm. Acesso em: 20 de ago. 2019.

OLIVEIRA, Carolina Bessa Ferreira de. A educação escolar nas prisões: uma análise a partir das representações dos presos da penitenciária de Uberlândia (MG). Educ. Pesqui., São Paulo, v.39, n.4, p.955-967, out./dez.,2013.

PLANALTO. Disponível em: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l7210compilado.htm. Acesso em 17 de set. 2019.

PAIVA, Vanilda Pereira. Educação Popular e Educação de Adultos. 5º Ed. São Paulo: Loyola, Ibrades, 1987.

PEREIRA, Antonio. A educação de jovens e adultos no sistema prisional brasileiro: o que dizem os planos estaduais de educação em prisões?

PRADO, Luiz Regis. Curso de direito penal brasileiro. vol. 3. 14. ed. São Paulo: RT, 2015.

SALLA, Fernando. As Prisões em São Paulo: 1822-1940. São Paulo: Annablume, 1999.

SANTANA, Maria Silvia Rosa; AMARAL, Fernanda Castanheira. Educação no sistema prisional brasileiro: origem, conceito e legalidade. Revista Jus Navigandi, ISSN 1518-4862, Teresina, ano 25, n. 6291, 21 set. 2020. Disponível em: https://jus.com.br/artigos/62475. Acesso em: 10 fev. de 2020.

SCHICHOR, David. The Corport Contexto of Private Prisions. Crime, Law and Social Change, v. 20, n.2p.113-138, 1993.

TAKADA, Mário Yudi. Evolução histórica da pena no Brasil. ETIC-ENCONTRO DE INICIAÇÃO CIETÍFICA, v.6 n.6, 2010.

VASQUEZ, Eliane Leal. 2008. Sociedade Cativa. Entre cultura escolar e cultura prisional: Uma incursão pela ciência penitenciária. Dissertação de Mestrado. 163 fls. Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo. São Paulo, 2008.

VELASCO. Clara. Menos de 1/5 dos presos trabalha no Brasil; 1 em cada 8 estuda. Disponível em: https://g1.globo.com/monitor-da-violencia-/noticia/2019/04/26/menos-de-15-do-presos-trabalha-no-brasil-1-em cada-8-estuda.gtml>. Acesso em 15 de set. 2019.

APPENDIX – FOOTNOTE REFERENCE

3. According to studies conducted there was no education that covered the deprived of liberty, this in turn was at the mercy of all kinds of violence, there was no public policy that benefited the prisoner, life had no value.

[1] PhD student in Educational Sciences (attending), Master in Educational Sciences (completed), Postgraduate in School Organization and Management, Postgraduate in Portuguese Language and Literature, Graduation in Letters and Higher Normal.

[2] Master in Educational Sciences (completed), Graduation in Letters (Completed) and Graduation in Nutrition (attending).

Submitted: August, 2020.

Approved: October, 2020.