ORIGINAL ARTICLE

CURVELO, Carmem Lana Pereira [1]

CURVELO, Carmem Lana Pereira. Subjectivity as a proposed approach to thinking about the assessment of students considered difficult: a method of applied psychoanalysis to think about malaise in education. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 04, Ed. 05, Vol. 03, pp. 114-128 May 2019. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/psychology/proposed-approach

ABSTRACT

The present article presents the results of the application of a methodology that was developed from an interdisciplinary experience for the investigation of the “problem-child”. This methodology consists of showing a study on the clinical-psychoanalytic construction of each student case, having The focus was on those students considered to be a real challenge for the school’s pedagogical team, due not only to learning difficulties in terms of reading and writing, but also considering other aspects such as the presence of disturbing behavior and inappropriate with teachers and classmates. The research was carried out in public and private schools in Belo Horizonte – Minas Gerais. From the analysis of the collected data, it was noticed the need to think about these students through the defended methodology, because it is able to make the faculty of the institution, after due analysis, look at these students in a more empathetic way to better understand this gap in learning and behavior. The teachers start from the principle that, in order to live in harmony, it is necessary that the events experienced in the classroom are re-signified from the child’s own history. The analysis of these interactions, in turn, provides strategies for the daily work with the students to be well done. It is a methodology that sought to investigate how subjectivity can contribute to the difficulty assessment process, avoiding the tendency to exclude students due to “indiscipline”.

Keywords: Problem children, Learning problems, Subjectivity, Inclusion, Psychoanalysis.

INTRODUCTION

Initially, it is necessary to point out that this article was born from the research project located in the area of Psychoanalysis and Education entitled “School care practices to think about the “problem child”: challenge of inclusion”, whose objective was to apply this methodology in an interdisciplinary case study – characterized as diagnostic, clinical and pedagogical. It was intended to observe learning difficulties and behavior disorders. This research was carried out in a State School of special education, located in the city of Belo Horizonte/Minas Gerais, and started from an invitation made by the School’s pedagogical advisor. It was hoped that case studies would be carried out focusing on some students considered real challenges for the school’s pedagogical team. These were children who had not only learning difficulties in reading and writing, but also disturbing and inappropriate behavior towards teachers and classmates, not to mention the frequent crises of agitation marked by violence, which imposed, in most cases, sometimes, emergency psychiatric intervention and, sometimes, there were cases in which there was police intervention.

Within this research axis, some questions took shape, mainly the following: what to do with these students who are counted as a “problem child” to alleviate school failure? The initial demand was that an in-depth investigation of these cases be carried out, through a clinical-pedagogical diagnosis to analyze the children’s learning difficulties in two different areas: one cognitive and the other related to the student’s subjective economy (Santiago, 2005). It was observed that these difficult students had already been studied, evaluated and diagnosed. In addition to having undergone numerous investigations, these children received all kinds of specialized attention: pedagogical and speech therapy re-education, they participated in therapeutic workshops, they underwent psychological follow-up as well as psychiatric control. This attention was also extended to parents, through guidance and family support programs.

Despite this, a new demand for a case study was made by the educational advisor, but this time based on the verification of the ineffectiveness of these various interventions carried out with those children. The professionals involved repeatedly faced the limits of their specialties. Even if, over the years, they have not stopped continuing their professional training, seeking continuous contact with new theoretical approaches that were launched, from time to time, in the knowledge market, there were many challenges in dealing with these children. The initial enthusiasm from the contact with other dimensions of a problem that possibly caused school failure, as well as his proposals for re-educational or psychotherapeutic intervention, ended up giving way to the conviction that some cases would remain as indecipherable enigmas.

What to do with the student who writes but cannot read? How to evaluate the one who, at home, speaks, but, at school, never uttered even a syllable, does not respond to any demand from the teacher? How to ensure the inclusion of those who, at the slightest frustration, break up the school? These are some of the questions that were reopened from the bet of the professionals of that school on the contribution of psychoanalysis to education. This perspective was adopted to think about where education’s malaise was located. This contribution awakened in those interested the need to understand the particularity of the subject, for that, these researchers went beyond the identifying offers proposed by the different theoretical approaches.

The initial contact with this issue was made through the thesis work entitled “Sobre a inibição intelectual na psicanalise” (Santiago, 2005), as it discusses the ways of diagnosing learning problems and the way in which the student can be identified as having a deficit. Due to the very nature of the evaluation process used, these diagnoses are unaware of the child’s need to make use of the meaning of school contents to inscribe their particularity and even to perceive, that is, to feel, these contents. It is not possible to say that every learning difficulty manifests itself from a symptom, but to say that it is necessary to investigate the process of formation of the unconscious.

In our view, ignorance of the subjective dimension leads to learning difficulties, which often makes any attempt at therapeutic intervention unfeasible, thus producing unwanted effects such as segregation and exclusion of students from regular education. It is known how much the therapeutic strategies to guarantee the subject’s access to a performance stipulated by the requirements of the norm end up culminating in impotence: it is not rare that the permanence of a learning difficulty lasts the entire school life of a child – and that, when she does not interrupt her school trajectory, due to the persistence of failure. This finding led to the proposal of a diagnostic procedure, called clinical-pedagogical, whose objective was to identify the status of the difficulty in two different spheres: one cognitive and the other related to the student’s subjective economy.

Cognitive assessment is based on the investigation of the child’s knowledge, in the strict plan of his mastery of the absolutely essential theoretical foundations for overcoming content errors. In addition to the theoretical mastery of contents, learning impasses are indicative of symptoms of intellectual inhibition. From this perspective, we seek to clarify the intellectual trajectory in which the child develops, from the solution of a task, to the precise point where his subjective impasse is located, the articulation of the content.

The clinical-pedagogical diagnosis methodology is inspired by two distinct theoretical approaches explored here, in a complementary way. The clinical method proposed by the cognitive approach to investigate the conceptual hypotheses present in the production of errors by the learner has the scope of exploring the method, as it is a fundamental process for deconstructing and overcoming them. On the other hand, the patient interview methodology is used – a central instrument of knowledge of psychiatric psychopathology – which, in the field of psychoanalytic practice, investigates how certain symptoms appear in the patient’s speech.

Thus, the child is questioned about his school difficulties, just as a patient is questioned about his symptoms. It should be noted that this investigative attitude is only possible when the interviewer puts himself in the position of not knowing in front of the other, stripping himself of the tempting role of master, which the adult normally tends to adopt in front of a child. The resource of listening to what the child herself has to say about her difficulty, that is, of taking into account what the subject knows about what happens to her, enables not only the elucidation of elements of subjectivity or unconscious meaning, but it adds the minimum of meaning that the school content must have, as well as a specific re-educational intervention method.

In short, the clinical-pedagogical diagnosis aims to reconcile the investigation of the processes of consciousness with conceptual thinking, as both undergo a process of knowledge development in the field of written language learning processes. As Jean Piaget already said (Ferreiro and Teberosky, 1985/1991; Kamii, 1989/1992; Oliveira & Nascimento, 1990; Oliveira, 1992; Alvarenga, 1993; Macedo, 1994), the psychoanalytic investigation of the primordial unconscious processes must be underlying the production of errors in the construction of knowledge. It is not only a research instrument, but also an intervention with children who have learning disorders. In other words, the clinical-pedagogical diagnosis is a treatment proposal for school difficulties that must be carried out within the school institution, aiming to avoid the exclusion of the child.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The use of this diagnostic proposal to carry out a case study on special education students revealed some limits and, as such, required the introduction of some modifications, making it necessary to propose complementary procedures, depending on the particularities of the difficulties of the student, such as, for example, the impossibility of direct contact with some of them. Due to the lack of access to certain student profiles, the criteria had to be rethought, as well as the possible collaborators in the study. As it is a methodology that deals with analyzing human consciousness, one of the biggest challenges was to interpret the particularities/individuality.

The professionals involved, making use of their specific knowledge, opted for a type of comprehensive case study, which included a study about the child’s school life, thus defending the need for an analysis that was concerned with understanding the written language and spoken, always thinking about the classroom environment (Castanheira, 2004). For this, a historical survey was carried out to recover psychiatric and psychological records of these students, for the analysis of this clinical picture. We sought to analyze how they behaved in interview sessions guided by the contribution of psychoanalysis, as it considers the formation of the symptom, the subject’s particularities and its psychic structure (Santiago, 2005). Thus, the clinical-pedagogical evaluation instrument started to be composed of three stages: case history, pedagogical evaluation and clinical evaluation.

The objective of the first stage – case history – was to establish a student profile based on the information provided about the student by the School’s professionals. Seek to delineate:

1) What is said about the student;

2) What theoretical elements are incorporated in this discourse, constructed in an attempt to explain the student’s problem; It is

3) What information from this speech is contradictory or vague.

It was intended to highlight, from the set of information gathered, what circulates among educators, the most relevant aspects that come to identify the student in the school space and, from these data, it was also verified whether such identifying offers they come from what is known about their family history, clinical antecedents, psychiatric trajectory, with the aim of assessing whether these factors shape their behavior at school or refer to evolution in the pedagogical plan. Still in this first stage, a study of the data recorded in the school records was carried out, seeking to establish a second student profile, whose objective was to seek and understand the reason for the referral to the special education school. The two questions that guide this study are:

1) What was decisive for the identification of the student as “having special needs”?

2) Is there an evaluation of the student in terms of school learning or does the complaint of behavior disorder stand out, indicating a difficulty in terms of the symptom?

Then, the student’s clinical history was understood based on the analysis of his psychiatric records, in which data were recorded about follow-up related to chemotherapy and/or therapeutic treatment. The second stage – pedagogical evaluation – foresees a series of observations about the student’s performance in the classroom and in the school environment, considering, for the evaluation, the following aspects: student interaction with the teacher, with colleagues and with learning and the teacher’s interaction with the student, with the class and with educational practices in the classroom.

Seeking not to highlight the target of his observation, the researcher was introduced to the class, which, in turn, stated its purpose in general, and, later, participated in the activities planned by the teacher in the classroom, interacting actively with with all students. The pedagogical production of the problem student was evaluated among the others, as well as the proposed forms of evaluation. The teacher and interviewee sought to clarify these aspects. In cases where this seems justified, an individual pedagogical assessment of the student was also proposed, aiming to situate the cognitive level at which he was found to work on recurrent errors in the perspective of their deconstruction.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Based on a clinical evaluation based on the analysis of interviews that took the procedure of “patient presentation” as a model, an attempt was made to interpret, along with it, the other stages based on the content recorded and transcribed with the consent of the interviewed, to proceed later to carry out a deeper analysis. The starting point of this clinical interview seeks to question, affectively, the child about his symptom, in this case, the difficulty at school based on the proposition of some questions: Why was he referred to special education or treatment? What is your school difficulty? At what point did it appear? How did it evolve?

What we seek to understand is how the student’s knowledge about what happens to him is configured, that is, what constitutes a malaise. At this stage, the parents or guardians can use a source that contains the main information about the interviewees, so they were consulted only to be able to situate themselves, as they presented the history of the child’s general development, with the child’s responses to what was asked of him offered, in terms of family relationships based on desires, ideals and modes of satisfaction most characteristic of the family group.

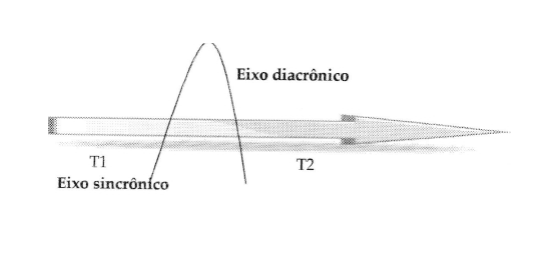

Based on the information gathered during this diagnostic process, the construction of the case is carried out. Of the set of facts, initially located in a diachronic sequence, only a few will stand out as symptomatic responses of the subject. This reading is done by retroaction, seeking to locate the production of the child’s symptom or difficulty in the synchronic axis, as represented below:

It is through this retroactive relationship that psychoanalysis locates the traumatic events of the subject’s encounters with reality and, on the other hand, highlights the symbolic effect of this encounter, personifying the symptom. For psychoanalysis, therefore, it is not possible to foresee that an event X, experienced in a time – T1 will have as a consequence, in a future time – T2 – the production of a symptom X. The time of the appearance of the symptom is always a T2, which produces a meaning effect on the trauma experienced in T1. This scheme – in which a meaning only takes place a-posteriori, by retraction – in the work of Jacques Lacan (1936/2001), has a polyvalent value. It was used not only to relate the trauma to the production of the symptom, but also to situate the transference, to formalize the subject’s desire in his relationship with the other, with the analyst and with knowledge.

Ultimately, this scheme lends itself to various formalities and thus constitutes the basic cell of the analytical relationship, to expose the very conception of the unconscious. The logic of this scheme guides the construction of the student’s case based on his symptomatic production, which has even allowed a diagnostic definition from the point of view of the psychic structure. This construction was presented to the school’s professionals, together with the intervention proposals designed for each case, taking into account the particularities of the subject. For one student, for example, a literacy workshop was proposed that used love letters as teaching support.

For another, whose case study showed the presence of delirium, the proposed referral, at first, was the adequacy of the medication to the condition (the student used only tranquilizers), to make it possible for him to stay at school. Given the impossibility of exposing, in this work, the results related to all the cases studied during the development of the project, it was decided to present in detail only one of them, to demonstrate the methodology employed.

CASE STUDY

One of the cases studied during the development of this project was that of a 13-year-old girl – at the time of the diagnosis, who will be designated here by the name of Lu. She was a repeat student, assiduous, and constituted an enigma for the pedagogical team. No teacher had managed, since joining the school more than six years ago, to carry out a pedagogical evaluation of the same. This was mainly due to the fact that she did not speak. Contrary to this finding, the child’s mother stated that, at home, she spoke normally. Another point raised as a difficulty in evaluating the student was the fact that Lu always presented her homework complete and done correctly.

On the other hand, at school, she did not respond to any request from her teacher and did not respond to any demand made to her. Therefore, she suspected that her older sister helped her in carrying out her duties. From the first profile of this student, established from what the school professionals said about her, these elements and the hypothesis of an autism condition stood out. In short, what identified Lu at school was being dumb and crazy, even being called “dumb girl” and “loony girl” by classmates. Reading the data recorded in the school and psychiatric records allowed the elaboration of the following diacritical sequence related to Lu’s history:

- 1988 – Birth of Lu.

- 1993 – Hospitalization due to nephritis, anemia and gastroenteritis (complications due to a severe case of malnutrition).

- 1993 – The mother notices her daughter’s strange behavior: irritability and poor communication with family members.

- 1994 – Attends pre-school for a year and three months, but learns nothing.

- The teacher observes that Lu did not accompany the class in activities or games, he does not say anything to her or to his classmates, he is beaten without reacting and does not cry when attacked. At that time, the educators suggested that the mother seek a doctor to evaluate her daughter.

- 1995 – First psychiatric and speech therapy consultation at the CPP – Centro Psicopedagógico: Lu is very agitated, squirms in her chair, shows nervous tics and does not utter a single word. Diagnostic indication: “Childhood psychosis?”

- 1996 – It is recorded in the medical record: “difficult contact and the presence of the other becomes threatening for the child”. Diagnostic indication: “Mental debility? Autism?”

The elements provided from the interview with Lu’s mother – Júlia – allowed the following construction: D. Júlia is separated from her husband and raises four children with the fruit of her work and the support of the church. Lu is the youngest daughter. The circumstances of the family romance, in this case, call attention. The first time D. Júlia saw the man who became her husband was in a church. The latter was drunk and semi-conscious, leaning over the pew of a church located in the center of the city, where Dona Júlia often went to say her prayers. Some time later, she finds him again in another church, located in a neighborhood. As before, he had been drinking alcohol and was semi-conscious.

This second time it happened! The drunken state of that man, with the good-natured air, staggering in the church pew, definitely touched Dona Júlia, who took it upon herself to meet him and guided the rest of the process, up to the wedding. She was never bothered by the fact that he was a frequent drinker. “My husband always drank, she says, but he wasn’t fighting, he wasn’t aggressive. He just drank and didn’t say anything.” He was a street vendor and supported the house. After getting married, D. Júlia began to increase the family, without this being the couple’s plan. “I was having the kids and he never said anything.”

However, in the fourth pregnancy, which came shortly after the third, the husband spoke about it, asking “Another one?” That simple statement produced a profound discomfort in Julia: even though she was still in the first month of pregnancy, she began to feel the fetus writhing in her womb, without a place. This feeling lasted the entire pregnancy, during which the expectation of a miscarriage prevailed. However, the baby avenged and was born at the right time. Lu is then born, according to Júlia, her most beautiful baby.

Lu developed normally, until the day when his father made a second consideration, saying to his wife: “Isn’t it time to wean this girl?” For the second time, a statement by her husband makes D. Júlia deeply uncomfortable. She then decides to throw away all of Lu’s bottles and pacifiers. In the evening of that same day, she says to her daughter: “As of today, there are no more bottles, because your father doesn’t want them.” Lu was just under two years old.

According to Júlia’s account, the daughter accepted this abrupt weaning without objecting, but from the next day onwards, she began to decisively refuse solid food. This problem was remedied with the purchase of new bottles. During the next three years, Lu is fed only through a bottle, gradually developing a serious condition of malnutrition, which culminates in her hospitalization.

Irritability and lack of communication with family members will characterize Lu’s behavior after the period of hospitalization, which lasted a few months. She also starts to show fear in front of anyone dressed in white clothes or in a lab coat, which is one of the characteristic reactions of hospitalism. On that occasion, Júlia tells him: “You don’t want to go back to the hospital, do you? If you don’t want to go back, you have to eat everything right.” Lu lets herself be fed, but her behavior worsens to the point that the clinicians recommend the special education school.

This story of Lu was presented to the teachers who worked directly with her. The unpretentious comment of the good drunken husband stood out, which, without a doubt, interfered with the place of desire reserved by the mother for her fourth baby. The position of the latter can be compared to that of the daughters of Lot, from the Biblical text, who, in order to guarantee the procreation of the human species, got their father drunk so that he, unconsciously, would fertilize them. The response that comes to the husband’s comment and a feeling of strangeness that falls on the fetus, associated with the idea that it no longer found a place in her womb and in the world.

In a second moment (T2), another comment by the husband – this time about weaning – gives meaning to what would have happened at the beginning of the pregnancy (T1). The mother understands that it is necessary to introduce a radical separation for the baby. Thus, weaning, which sooner or later happens to every subject, is linked to a meaning that was initiated by the husband regarding the mother’s relationship with her offspring. The subject responds with anorexia, which is not only a refusal to let himself be fed, but also a refusal of the maternal other, of the meaning found in the field of desire of this Other. As a response from the subject, a response from reality, this symptom remains veiled, that is, it does not receive an interpretation and, later, it is named and treated as malnutrition.

The interview with the mother explains the enigma of speech. In fact, at home, Lu didn’t speak either, he just uttered some meaningless sounds, when he listened to records with church music: “She speaks, but at those times, she speaks English.” The observations made in the classrooms and during break times, showed Lu’s concern with the limits of her body for example, she would curl up, bend over, and use the braces to spiral herself into a spiral, as if the hand extended toward her could penetrate her body.

At the time of recreation, she was usually alone, leaning against the wall, hiding behind her long black hair, pressing her back against the wall and pulling her stomach in, every time a child ran past her. In the living room, she sat facing the door, watching who went in and out. She was afraid to go through the side of the door. When it was time to leave the room, she was anxious, insecure. One day the teacher offered her a hand to help her overcome this limit. After that, she always looked forward to this help. The importance of Lu’s contact with the teacher was highlighted, to which this teacher asks: “Wow, what a responsibility! What should I do?” to which he was replied: “Don’t do anything different. Just allow her to do it.”

After this presentation, Lu’s progressive change at the School surprised everyone. “Before, she represented herself, in the classroom, as a dot in the corner of a sheet. Recently she made a drawing representing herself as a baby, in a crib, taking several bottles. I remembered her story”, said the teacher. “Before, he hid from everyone. Now, when I’m picked up to do something, she’s the first to want to show it off. She lifts her notebook and grunts until I talk about her exercise: “These two testimonies exemplify, in our view, the possible invention, in the classroom, from the introduction of some elements of the subjectivity of difficult students.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The therapeutic effects of this experience on the student and the changes presented by her in the field of pedagogical activities led the teacher to seek out an educational advisor to discuss the feasibility of an educational work, which, initially, put the purpose of literacy in abeyance. This proposal had already been conceived, but never put into practice. Thus, they constituted a group of girls, in which school delay was no longer what identified the elements of the group, but what could be identified as the desire of the students. What could be of interest to these teenagers, aged between 12 and 14, who, like Lu, had been going to school for many years and had not learned to read and write? This was the first question posed to the class on the first day of class. They chose to learn how to paint their nails, get to know hair products and talk about fashion. They started calling each other nicknames: dumb, tapir, big chest”… “dumb girl” was Lu’s nickname.

The teacher drew the attention of the girls to these nicknames. She told them that when she was a student, she was called skinny girl because she was so skinny-and she didn’t like that. She also said that they were part of a new group that had made progress in learning and, therefore, they should find other ways of treating each other, other identifying alternatives that would make the group’s proposal to be a group of young women worthwhile. The activities carried out by the group included walks around the school to observe what might interest them as young girls. On one of these walks, when they saw boys in a public square, the female students whistled at them, making jokes. This fact embarrassed the teacher who decided to return immediately to the school and discuss with them the adequacy of the group’s behavior, in view of the new identity they sought to build.

In her intervention in this regard, the students said: “That’s not the case, because I’m married and I’m not going to go out there with girls who sing about men in the street.” It can be noted in the types of comments that the teacher starts to make with this group, the introduction of elements of her own subjectivity, a characteristic that was hardly observed before in her didactic work in the classroom. On one of several out-of-school excursions the class watched with great interest belly dancing classes at a gym. The contact between the group’s teacher and the dance teacher resulted in the offer of free classes to the group, which initially withdrew out of fear, but then accepted.

Although this opportunity was a contingency, from the offer of a person who had no institutional connection with that group of students, it ended up constituting the engine of the desire to learn and allowed the initiation of the literacy process: initially, the students expressed a keen interest in learning the numbers to mark the times of the dance. Later, due to the public presentation they were going to make, they wanted to learn to read and write their own name and that of the teacher so that they could read them on the publicity posters. Throughout this process, Lu was welcomed and helped by her colleagues, and she responded by demonstrating that she had acquired the possibility of including other people in her relationship, without panic.

It is concluded that it is possible, with the proposed methodology, to increase students’ awareness of the subject, provide them with tools to identify and value their opportunities and qualities, and, fundamentally, we can encourage people to believe in their potential, to dream high and make dreams come true. Therefore, this work is aimed at professionals of the new times, who are committed to taking these students away from the margins where they live, effectively inserting them into the school environment, so that they have the courage to take risks and are not afraid to transform dreams into reality.

BIBLIOGRAPHIC REFERENCES

E. DUMAS, Jean. Psicopatologia da Infância e da Adolescência, Artmed, 2011.

GURSKI, Rose; DEBIEUX ROSA, Miriam; POLI; Maria Cristina. Debates Sobre a Adolescência Contemporânea e o Laço Social, Juruá, 2012.

GUTIERRA, Beatriz Cauduro Cruz; Adolescência, Psicanálise e Educação- O Mestre Possível de Adolescentes; Avercamp, 2003.

HABIGZANG, Luísa Fernanda; DINIZ, Eva; KOLLER, Silvia;, Trabalhando com Adolescentes- Teoria e Intervenção Psicologica, Artmed, 2014.

LEVISKY, David Léo; Adolescência Reflexões Psicanalíticas, Zagodoni, 2013.

MURATORI, Filippo; Jovens Violentos- Quem são, o que Pensam, Como Ajudá-los? Paulinas, 2007.

RAPPAPORT, Clara Regina; Adolescência: Abordagem Psicanalítica; Epu, 1993.

[1] Master in Business Sciences, with an MBA in Higher Education and Controllership and Judicial Expertise.

Submitted: January, 2019.

Approved: May, 2019.