ORIGINAL ARTICLE

ROCHA, Felipe Queiroz Dias [1], PICCIONE, Marcelo Arruda [2]

ROCHA, Felipe Queiroz Dias. PICCIONE, Marcelo Arruda. How working seniors rate their quality of life. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year. 06, Ed. 11, Vol. 09, p. 112-131. November 2021. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/psychology/working-seniors, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/psychology/working-seniors

ABSTRACT

Old age results in changes in the elderly due to: existential crisis, maladjustment to new functions, reform and reduction of social contacts. Most elderly people who continue to work belong to disadvantaged social classes, but there are elderly people who show dissatisfaction with being retired and try to return to work to feel energized. In view of this scenario, the present article is guided by the great appreciation of the quality of life in the elderly. The objective was to examine how the elderly who work rate their quality of life. Thirty-six seniors who were still working participated in the research, with a mean age of 71,5 and ± 5,4. Data was collected accidentally in the city of São Paulo. For this, 36 identical WHOQOL questionnaires and Termo de Consentimento Livre e Esclarecido (TCLE)[3] were used. To find out if there is a statistically significant difference, the non-parametric chi-square test was applied. As a result: 80,55% say they Totally agree with the premise that God cares about his problems; 63,88% Totally agree that they have a significant relationship with God; 50% are Satisfied with their sleep and 38,88% rate their need for daily medical treatment as Nothing. It is noticed that the elderly workers are mostly satisfied with the quality of the observed aspects of their lives.

Keywords: old age, retirement, retirees, third age, seniors.

INTRODUCTION

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), quality of life is a measure that is based on three distinct and concomitantly essential axes: the fact of being multidimensional, subjective and encompassing negative and positive details. This thematic object can be defined as an individual’s perspective on their position in the culture of the social environment in which they live, in relation to their goals, objectives, concerns and standards (TRENTINI; XAVIER and FLECK, 2006).

In fact, quality of life has several concepts in different areas of knowledge. For example, in the field of Economics, it is linked to indices, such as per capita income, which show the access of populations to basic services (education, health and housing). In the field of Politics and Sociology, attention is directed precisely to one category. In Social Psychology, the main parameter of this concept is the degree of satisfaction of an individual’s particular experience. That is why there has been a great appreciation of the quality of life in the elderly in recent years (TRENTINI; XAVIER and FLECK, 2006), which will guide our focus in this research with a group of remnants at work.

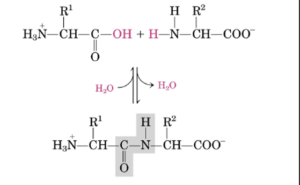

The aging process can be classified in three ways, according to its development: the first is called old age with pathology and is denoted by the presence of a chronic disease or disability that severely restricts the individual’s common activities, so that their functions once performed are markedly weakened (TRENTINI; XAVIER and FLECK, 2006).

In the second, usual or normal old age, the emergence of mild or moderate physical or psychological pathologies is quite common, which cause only subtle changes in the subjects’ daily lives (TRENTINI; XAVIER and FLECK, 2006).

Finally, the third class of aging is known as successful or optimal old age and is characterized by the maintenance of health as in the youthful period, in order to reflect on the subject’s well-being (TRENTINI; XAVIER and FLECK, 2006).

Aging consequently implies the emergence of inherent and gradual biopsychosocial changes that vary in their extemporaneousness and proportion, according to biogenetics and, mainly, the lifestyle of each subject. Some practices that can mitigate the impacts of the course of time are: maintaining a balanced diet, doing physical activities, carefully exposing yourself to solar radiation and mentally inciting yourself. Thus, it is understood that old age is a stage in which the organism is more prone to develop pathologies, which is different from being a disease (ZIMERMAN, 2000).

In other words, aging is not a pathology, but a unique process of human development in each subject. It is also important to consider that the diseases resulting from this phase are possible to undergo intervention at three levels (prevention, diagnosis and treatment). Furthermore, seniors can have quality of life even if their bodies are depleted and exhausted (MARTINS et al., 2007).

According to research, the elderly constantly need support in dealing with their health and are commonly helped by family members (ABREU and MATA, 2001).

It is worth mentioning that healing practices are more privileged by the system than educational ones. Thus, carrying out actions aimed at education concerning the health care of seniors turns out to be a challenging job (MARTINS et al., 2007).

It is important to highlight that: in relation to satisfaction with health, 45% of seniors said they were satisfied, while 40% reported being satisfied with their ability to work (COLALTO, 2002).

In fact, one of the aspects that can lead to early retirement is health status. Presumably older people who delay discontinuation do well in this regard (BEE, 1997).

In addition, some men and women who have children very late, or have formed a new family through another marriage, or those who care for grandchildren, are supposed to continue to work until those connected to them leave their home (BEE, 1997).

Most elderly people who continue to work belong to disadvantaged social classes and do so to help maintain their posterity, who often return to their family of origin due to unsuccessful relationships (COUTRIM, 2005).

Another issue that may help the elderly to avoid retirement is not obtaining a solid economic condition during the time of work activity and the lack of financial support from their children (BREVIGLIERI, 2002).

It is worth noting that only 5% of the elderly report being completely satisfied with having enough money to meet their needs (COLALTO, 2002).

In a society where people are qualified according to their performance, asking becomes an act that connotes incapacity. As a matter of fact, asking has never been part of the identity of the elderly, especially because subjects from a young age are encouraged not to be dependent and the relativity and plurality embedded in the concept of independence are never mentioned (ZIMERMAN, 2000).

However, the elderly person refrains from asking for any kind of help because they feel they cannot do it, they do not want to be inopportune, they think that the occupation of their descendants is more significant than their needs and aspirations, they fear being labeled as impertinent and having their status as a productive and independent subject deconstructed (ZIMERMAN, 2000).

On the other hand, there are elderly people who show dissatisfaction with being retired. There are seniors who try to return to the profession to feel nimble and encourage their spirits and self-image (BREVIGLIERI, 2002).

In fact, the elderly must plan actions that allow them to have satisfaction at this stage, and this requires getting new habits, getting involved in profitable activities, fulfilling their personal plans and desires, studying at a senior university, doing volunteer work or other practices. In other words, successful old age depends on how seniors deal with the misfortunes that befall them, plead for their rights and perform plausible actions given their reality (MARTINS et al., 2007).

In fact, happiness is an indicator of quality of life, which may be associated with attendance at religious ceremonies and doctrinal preferences. Religion considerably influences the individual’s perspective of the world, justifies the meaning of life and, thus, provides satisfaction (PANZINI et al., 2007).

Religion is an experience that needs to convert the subject, an adversity that needs to transform and touch the individual, and not be limited to being a system composed of dogmas, beliefs and norms, but of a personal faith, which typifies the particular knowledge of the divinity. The meeting of this sacred space is something subjective (DINIZ, 2003).

Thus, some elements, such as rites (acts) and myths (speeches), underlie every creed and are, therefore, the ratifiers of the symbols created for the manifestation of the deific. In this way, religion can be defined as the assumption of transcendental realities that consciousness cannot understand and, when taken to full psychological enjoyment, produces the uniqueness of the interior and human fullness (BAPTISTA, 2003).

In fact, there is no distinction between the different lifestyles maintained by seniors in prayers. Most say prayers for: health, receiving peace, for love, family issues and to give thanks (ORLANDO et al., 2008).

It is noted that the spiritual life has a very high value in old age, so that an entire group surveyed said they conform to some creed. The reason for this is the chance that a belief gives them to establish a connection between their impossibilities and the use of their abilities; or, when this does not occur, it helps him to deal more easily with the finitude of this last stage of life (ARAÚJO, 1999).

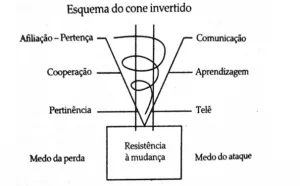

Thus, old age is a stage that results in changes in the subject’s status, as well as in his/her relationship with the other due to: existential crisis; change of position in the family, social and labor nuclei; remodeling; miscellaneous losses; decrease in social contacts due to its restrictions (ZIMERMAN, 2000).

These modifications also compromise sleep. In the course of the usual aging process, changes occur in the quantity and quality of rest that affect more than half of individuals over 65 years of age who live at home and 70% of those institutionalized, in order to negatively impact their quality of life(GEIB et al., 2003).

The changes cause alterations in the homeostatic system and affect: psychological aspects, immune system, responding behavior, general daily performance, adaptability and mood. The causes that usually cause this type of disorder in old age are: pain, environmental factors, emotional discomfort and changes in sleep patterns, such as increased latency, difficulty in restarting sleep and reduced duration (GEIB et al., 2003).

In addition to these complaints, daytime drowsiness and fatigue are common, as are increased naps, impaired cognitive and day-to-day performance, and a host of other problems, which, while not specific to aging, have a major impact on the elderly. The lack of adaptation to emotional disturbances, inappropriate habits, some organic and affective disorders, the use of substances (psychotropic or others), night restlessness and falls are possible consequences. These symptoms allow us to affirm that sleep and rest are essential restorative functions for the maintenance of life (GEIB et al., 2003).

Among the psychosocial factors responsible for sleep disorders in the elderly are grief, retirement and changes in the social environment, such as isolation, institutionalization and financial difficulties. The death of a spouse has a strong impact on old age, and may or may not be associated with depression. Retirement and changes in the social environment, when they break with the normal habits of the elderly, contribute to reducing the amplitude of the sleep-wake rhythm, producing fragmentation of nocturnal sleep and naps during the day, used as an escape from monotony (GEIB et al. , 2003).

Another significant factor in the difficulty of the elderly to sleep is the intensity of chronic pain (ALVES et al., 2019).

However, in addition to changes in the body, aging brings to the human being a series of psychological transformations that can result in maladjustment to new functions, demotivation, difficulty in organizing the future, lack of support to deal with organic, emotional and social losses, difficulty adapting to rapid changes, psychic changes that require professional support and a lack of self-esteem and self-image (NERI, 2001).

According to international studies, 15% of the elderly need psychological support and 2% have depression. Often, these demands are not identified by the family and caregivers, instead they are taxed as peculiarities of the old age stage (ZIMERMAN, 2000).

In fact, only 40% of the elderly report being satisfied with the health service they have (COLALTO, 2002), although they agree in saying that they are not satisfied with such medical assistance due to the impossibility of talking about their complaints and not being asked questions. Sometimes, professionals do not even look at them directly (BERES, 1994).

The senior’s conversation with the health professional generates interpersonal exchanges, which, together with the knowledge already popularly disseminated, help to overcome flaws present in the traditional health educational exercise. Therefore, there is a possibility for the elderly to request their interests autonomously as social subjects capable of doing so (MARTINS et al., 2007).

The general objective was to examine how elderly workers rate their own quality of life.

The specific objectives are:

- To analyze the progress of some aspects of the lives of the elderly who continue to work;

- Hear from seniors who are still working how some aspects of their lives are doing;

- Critically check the state of some aspects of their lives.

METHODOLOGY

PARTICIPANTS

This research had 36 elderly people (88,90% men and 11,10% women) as participants, who were 65 years of age or older (which is the age group defined by the WHO for the reform) and who were working with or without employment relationships, constantly or inconstantly. It was found that the age range is 22 years (the lowest age is 65 and the highest is 87), the mean age is 71,5 years, the standard deviation is 5,4 and the median is 71 years.

MATERIAL

The material used was the WHOQOL questionnaire; there were 36 units equal to each other to collect the data. This instrument was chosen due to its international recognition to examine the quality of life in its various aspects.

The instrument was a questionnaire divided into three stages: the first to characterize the participant; the second part consisted of a series of closed questions about various aspects that make up the general understanding of what quality of life is in the scope of Social Psychology; the last part contained affirmative and negative sentences that allowed the participant to expose their perception of them in relation to their context – that is, there was a series of sentences in which the participant reported to what degree he agreed or disagreed with them regarding his life.

PROCEDURES

Data collection was done by chance: the subjects were searched for and found accidentally in the months of January and February and if they were in the conditions established by the objective (working and who were 65 years of age or older) they were admitted by the researchers.

At the first moment we introduce ourselves and explain the purpose of our research. Subsequently, if the individual complies with our research objectives and voluntarily accepts to participate, we introduce the TCLE and the WHOQOL questionnaire, as well as provide any type of clarification about these documents and their items, which contained our contacts. It is important to highlight that the present work is part of a larger project, which was approved by the Research Ethics Committee nº 017/2005 and CAAE 005.0.237.000.05.

All participants were approached in the city of São Paulo, with the vast majority found in neighborhoods close to each other: 15 in Mooca, 6 in Brás, another 6 in Sé, 5 in Zona Cerealista, 3 in Vila Mariana and 1 in Cambuci.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Some results obtained in the WHOQOL questionnaires used will be presented and discussed statistically and critically in the following tables.

Table 1 – Occupation

| Areas | F | % |

| Sciences and arts area | 10 | 27,77 |

| Sales and commerce area | 15 | 41,66 |

| Industrial Goods Area | 8 | 22,22 |

| Another | 3 | 8,33 |

| Total | 36 | 100 |

Source: WHOQOL questionnaires.

In Table 1, it is noted that, among the participants, 41,66% are workers in the Sales and commerce area, 27,77% work in the Science and Arts Area, 22,22% are in the Industrial goods area and only 8,33% reported belonging to Another area.

According to the non-parametric Chi-square test – which was applied to verify if there is a statistically significant difference – there is no statistically significant difference, given: xo2=2,35 and x2c=7,81, in addition to n.g.l.=3 and α= 0,05.

The variables in Table 1 were systematized according to the categories of the Classificação Brasileira de Ocupações (CBO)[4], mentioned on the website of the Ministry of Labor and Employment: http://www.mtecbo.gov.br. The CBO occupations that were not among those practiced by the elderly were discarded from the table.

The material used raises the profession of each participant, but does not investigate the path that led the subject to choose this area of activity, his path or the circumstances that led him to exercise his current profession, so that it is totally imprecise to propose any hypothesis that detail your industry based on any other data obtained from the data collection and the literature consulted. What can be done is to discuss hypotheses of possible reasons why volunteers continue to practice these activities.

Coutrim (2005), for example, says that most of the elderly who continue to carry out work activities are from disadvantaged social classes, which require their collaboration in the family budget for the subsistence of their posterity, as their children commonly return to work their homes for failing in their relationships.

In agreement, Breviglieri (2002) says that the lack of economic stability during the years of work and financial support from the children also confirms that the elderly do not retire, in order to demonstrate the need to return to paid activities. Bee (1997) enriches these words by saying that late paternity or maternity, as well as the constitution of another family, may require the subject to remain at work until their dependents have enough conditions to maintain themselves, which should procrastinate his retirement as a result.

It is worth mentioning that Colalto (2002) says that only 5% of the elderly say they are completely satisfied with having enough money to satisfy their needs and 40% of the elderly are satisfied with their ability to work.

In fact, Bee (1997) also says that one of the factors that can advance retirement is health status. Presumably older people who stop late are doing well in this regard.

In this way, it is observed that the economic need is one of the main reasons that leads to the permanence of seniors in the labor market, which, on the other hand, tends to depend on the subject’s health status, since this aspect can lead to early retirement. Thus, the elderly may be in a paradox: while they need to work, they cannot or cannot do so due to their physical conditions.

Furthermore, Zimerman (2000) says that asking is an act that is not part of the identity of the elderly nor a well-regarded social construct, since society evaluates citizens for what they are capable of producing. The senior avoids requesting any type of support because: he feels he does not have this right, he does not want to cause discomfort, he believes that the occupation of his children and grandchildren is more important than his needs and desires, he fears being considered inconvenient and finally he is or feels stripped of its status as a productive and independent subject. About this last cause, Breviglieri (2002) says that there is some difficulty for the elderly to remain retired; seniors expressed a desire to return to work because they wanted to feel energized and boost their spirits and self-image.

Work is a facet that makes up the self-image of the elderly, the rupture with the job tends to hurt their perspective of themselves and as a consequence changes the way the subject deals with family members and other people, as the senior often worked and participated of the creation of these individuals who today have to support and help him, which is not easily accepted. According to Zimerman (2000), this effect of old age modifies the status of the elderly due to: existential crisis, change in roles concerning work and society, retirement, various losses, financial situation and other reasons.

Table 2 – Need for medical treatment for daily life

| Necessity | F | % |

| Nothing | 14 | 38,88 |

| Very little | 6 | 16,66 |

| More or less | 8 | 22,22 |

| Quite | 7 | 19,44 |

| Extremely | 1 | 2,77 |

| Total | 36 | 100 |

Source: WHOQOL questionnaires.

In Table 2, regarding the need for medical intervention, Nothing was the option most answered by the participants with 38,88%. In addition, 22,22% of the elderly chose the variable More or less, while 19,44% and 16,66% of the research subjects chose the variables Quite and Very little, respectively. Only 2.77% were in Extremely need of medical treatment.

The chi-square test was applied in order to verify if there is a statistically significant difference. The result was: xo2=4,42 and x2c=9,48, with no such difference, considering also n.g.l.=4 and α=0,05.

In this way, medical treatment, despite most opinions related to Nothing and Very Little Need, is present in the context of the elderly.

Trentini; Xavier and Fleck (2006) discuss old age with pathology, both usual and successful, which correspond to the development of human aging: the first accompanied by physical or mental dysfunctions that critically limit the actions of the elderly, the second the emergence of these dysfunctions in a mild content that causes only partial changes and the third with the full conservation of health as young adults. Based on this classification, it can be said that participants who reported as Nothing (38,88%) their need for medical treatment on a daily basis enjoyed a successful state of old age, while those who said Very Little or More or Less (38,88%) have a usual old age process, while the 22,22% who categorize their need as Quite or Extremely have an old age with pathology.

It is possible to reclassify these data if we consider that participants who report their need for daily medical treatment as Very little have a successful old age because we know that many young adults eventually develop health problems that also require daily treatment, so that little more than half (55,54%) would enjoy a successful old age and 22,22% a usual old age, which in the end, would continue to denote the smaller part of the volunteers as holders of the aging process with pathology and a slight majority as usual or successful seniors.

Zimerman (2000) corroborates the words of the trio when saying that aging predicts biopsychosocial changes in a natural and gradual way and to a greater or lesser degree, depending on the subject. The effects of these changes can, according to Bee (1997), determine the continuity of work, since the healthy state is a relevant factor for its continuation, which postpones retirement.

Martins et al. (2007) complement by saying that aging is a phenomenon that unfolds in a unique way in each individual, and not a pathology, even because the diseases resulting from this stage are susceptible to diagnosis, treatment and prevention. However, according to Colalto (2002), 45% of the elderly are satisfied with their own health and 40% are satisfied with the health service they have. Beres (1994) goes further and says that the elderly are unanimous in reporting their dissatisfaction with the medical care received due to professionals not giving them time to talk about their complaints, not asking questions and sometimes not even looking directly at them.

According to Martins et al. (2007), the appreciation of interpersonal exchanges permeated by dialogue between the patient and the doctor can help to overcome the gaps present in the educational exercise of traditional health if one considers the importance of popular knowledge. Thus, there is a possibility for the autonomy of the elderly as social subjects capable of demanding their interests. In addition, it is possible for the elderly to live well and with quality even if their body is exhausted or depleted. According to Zimerman (2000), a balanced diet, physical activity, careful exposure to solar radiation and mental incitement are some actions that can alleviate these impacts of aging.

In turn, Abreu and Mata (2001) report that research carried out with the elderly on the need for help in health care shows that all subjects receive help from their families in this context. However, as stated by Martins et al. (2007), the system favors healing actions more than educational ones, so as to procrastinate them as a consequence. Hence, promoting a good education regarding the health care of seniors becomes a challenging job.

Table 3 – Sleep satisfaction

| Pleasure | F | % |

| Very dissatisfied | 1 | 2,77 |

| Dissatisfied | 5 | 13,88 |

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 8 | 22,22 |

| Satisfied | 18 | 50 |

| Very satisfied | 3 | 8,33 |

| Total | 36 | 100 |

Source: WHOQOL questionnaires.

As seen in Table 3, half (50%) of respondents say they are Satisfied with their sleep. Thus, another 22,22% chose the alternative Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied. On the other hand, 13,88% consider themselves Dissatisfied, while 8,33% and 2,77% evaluate their choices as Very Satisfied and Very dissatisfied.

It is worth noting that xo2=8,96 and x2c=9,48, and the chi-square test was applied in order to determine whether there is a statistically significant difference; it turned out that such a difference does not exist. It is still known that n.g.l.=4 and α=0,05.

Participants who are satisfied to some extent with their sleep are 58,33% (those who classified themselves as Satisfied and Very Satisfied), a number that is significantly similar to those who report the need for daily medical treatment as Nothing and Very little, in Table 2: 55,54%. Thus, it is understood that good health, which eliminates the constant need for medical resources, can be associated with sleep quality (or vice versa). This equation may also be related to the words of Trentini, Xavier and Fleck (2006) regarding the three types of old age: those who say they are Satisfied and Very satisfied (58,33%) have a successful process, those who report as Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied (22,22%) have a usual aging process and those who consider Dissatisfied and Very dissatisfied (16,65%) go through the stage with pathology. When considering this prism, it can be seen that more than half of the participants have an excellent development, just under ¼ go through this stage in a usual or normal way and 16,65% have it with pathologies.

On the other hand, the results in Table 3 are incompatible with those cited by Geib et al. (2003) on the elderly who do not work and are institutionalized; the authors say that the usual aging process causes changes in the quantity and quality of sleep and, thus, affects more than half of individuals aged over 65 who live at home and 70% of those institutionalized, which has a negative impact on sleep your quality of life.

About this, the same authors (GEIB et al., 2003) say that these modifications also cause alterations in the homeostatic system and extend to: psychological aspects, immune system, responding behavior, general daily performance, adaptability and mood state. The causes that usually cause this type of disorder in old age are: pain, environmental factors, emotional discomforts and changes in sleep pattern (such as increased latency, difficulty in resuming sleep and reduced duration), drowsiness, daytime fatigue, increased naps, cognitive impairment and other symptoms that are not typical of aging but have a great impact on the elderly.

Geib et al. (2003) also say that the inability to adapt to emotional disturbances, inappropriate habits, some organic and affective disorders, substance use (psychotropic or others), night restlessness and falls are examples of possible consequences. All this symptomatology allows us to affirm that sleep and rest are restorative functions necessary for the maintenance of life.

Among the psychosocial factors responsible for sleep disorders in the elderly are grief, retirement and changes in the social environment, such as isolation, institutionalization and financial difficulties. The death of a spouse has a strong impact on old age and can be associated with depression, while retirement and changes in the social environment, when they break with the common habits of the elderly, contribute to reducing the amplitude of the sleep-wake rhythm, which produces the fragmentation of nocturnal sleep and naps during the day, used as an escape from monotony (GEIB et al., 2003).

From the biological perspective, Alves et al. (2019) say that chronic pain is a factor that significantly interferes with the sleep of the elderly.

Table 4 – Lack of certainty about the meaning of human existence

| Uncertainty | F | % |

| Totally agree | 5 | 13,88 |

| Partially agree | 5 | 13,88 |

| Agree more than disagree | 4 | 11,11 |

| Disagree more than agree | 6 | 16,66 |

| Partially disagree | 8 | 22,22 |

| Totally disagree | 8 | 22,22 |

| Total | 36 | 100 |

Source: WHOQOL questionnaires.

The results in Table 4 show that there is a balance between opinions about the meaning of human existence. Most of the interviewees, 22,22%, appear both as the final percentage of those who opted for the Partially Disagree alternative and the Partially disagree alternative. In addition, 16,66% chose Disagree more than agree, 13,88% said: Partially agree, others 13,88% Totally Agree and 11,11% Agree more than disagree.

In order to determine whether there is a statistically significant difference, the non-parametric chi-square test was applied, which resulted in: xo2=3,44 and x2c=11,07, with no statistically significant difference. It is also considered n.g.l.=5 and α=0,05.

Panzini et al. (2007) say that religion influences the perspective that the individual has of the world, can explain the meaning of life and bring satisfaction. In this sense, it can be seen in Table 5 that 94,43% of the elderly workers agree to some degree with the premise of having a significant personal relationship with God, while in Table 6 it is seen that 97,21% agree to some extent that God cares about your problems.

Baptista (2003) defines religion as the understanding of transcendental realities not understood by consciousness, which lead to inner unity at its apex.

It is observed that the impact of a religious belief for the elderly is very high, however, this aspect does not seem to fully determine the perspective that the subjects have about the meaning of human existence, given the leveling of responses presented in Table 4. That is, there is a possibility that this variable will influence your worldview, not a guarantee.

Table 5 – Significance of the personal relationship with God

| Meaningfulness | F | % |

| Totally agree | 23 | 63,88 |

| Partially agree | 7 | 19,44 |

| Agree more than disagree | 4 | 11,11 |

| Disagree more than agree | 1 | 2,77 |

| Totally disagree | 1 | 2,77 |

| Total | 36 | 100 |

Source: WHOQOL questionnaires.

It is observed in Table 5 that among the elderly participants in the research, 63,88% Totally agree that they have a significant relationship with God, among the other interviewees, 19,44% Partially agree, 11,11% said they Agree more than disagree, 2,77% of the elderly Disagree more than agree and another 2,77% Totally disagree. The Partially Disagree alternative was not chosen by any participant and was therefore removed from the table.

To verify if there is a statistically significant difference, the non-parametric chi-square test was applied. It was obtained xo2=8,53 and x2c=9,48 were obtained, with no statistically significant difference. It is also considered n.g.l.=4 and α=0,05.

Orlando et al. (2008) say that most of the elderly pray for goals such as health, peace, love, solving family issues and being grateful for favors achieved, which configures a type of relationship with God through these petitions.

Diniz (2003) says that the personal encounter with God through faith, in addition to the dogmas and norms pre-established by the belief system, touches and transforms the individual, and it is this point that characterizes religion. Baptista (2003), in turn, understands religion as the assumption of transcendental realities that consciousness does not understand and when taken to full psychological enjoyment produces the totality of the human being inside, although he considers that rites and myths underlie the construction of all religions and they are, therefore, the validators of the symbols created for the expression of the sacred in us.

Araújo (1999) continues to say that this aspect has a great influence on old age, so that 100% of the population who researched said they conform to some creed. This adherence is due to the fact that the practice of a religion by the elderly allows them to establish a connection between their impossibilities and the use of their abilities or, when this does not occur, it helps them to deal more easily with this final stage of life.

Panzini et al. (2007) completes by saying that doctrines and attendance at religious ceremonies promote happiness, instigate the world view and explain the meaning of life.

Furthermore, Table 5 shows that 94,43% of the participants say that they somehow agree with the premise of having a significant personal relationship with God, similar to Table 6, in which 97,21% agree in some way that God cares about your problems. In addition to the high spirituality index verified in these two results, it is possible to correlate them with each other and understand that the personal relationship with God can occur due to the concern of the Divine Being with the problems of the devotees, in order to configure a favorable context for the relationship interpersonal relationship in a spiritual framework and the construction of symbols and dogmas arising from this same relationship.

Table 6 – God’s concern with problems

| Variables | F | % |

| Totally agree | 29 | 80,55 |

| Partially agree | 4 | 11,11 |

| Agree more than disagree | 2 | 5,55 |

| Partially disagree | 1 | 2,77 |

| Total | 36 | 100 |

Source: WHOQOL questionnaires.

Observing Table 6, it is noted that 80,55% of the participants Totally agree with the statement that God cares about their problems. Only 11,11% Partially agree and 5,55% Agree more than disagree. Only 2,77% Partially disagree. The alternatives Totally disagree and Disagree more than agree were eliminated because they were not mentioned by any subject.

It is worth mentioning that xo2=0 and x2c=7,81; once the chi-square test was applied with the intention of finding out if there is a statistically significant difference; it turned out that there is no such difference. It should also be noted that n.g.l.=3 and α=0,05.

According to Orlando et al. (2008), most elderly people pray for purposes such as health, peace, love, solving family problems and gratitude for favors obtained. The practice of these prayers denotes their belief in the divine concern for their problems, because through prayer their complaints are presented to be resolved in this sacred space, in the words of Diniz (2003).

The same Diniz (2003) defines religion as a transforming experience of the individual, not a concrete system composed of morals, doctrines and creed, but a faith that produces a personal encounter with God. The experience of this sacred space is strictly subjective. Panzini et al. (2007) corroborates by declaring that happiness is associated with participation in religious services and doctrinal preferences, which significantly influence the individual’s view of the world.

Baptista (2003), in turn, conceptualizes religion as the assumption of transcendental realities that consciousness cannot understand and which, taken to full psychological enjoyment, leads to the uniqueness and inner totality of the human being.

According to Araújo (1999), the spiritual aspect greatly influences this stage of life, so that 100% of its participants said they were in compliance with some religious activity. As for the reasons for the occurrence of this fact, it appears that the practice of a religion by the elderly allows them to establish a link between their impossibilities and the use of their abilities or, when this does not occur, it helps them to deal with this problem last stage of life.

Furthermore, Table 6 shows that 97,21% of the participants agree to some degree that God cares about their problems, a similar percentage to Table 5, which says that 94,43% agree to some extent with the premise of having a meaningful personal relationship with God. The very high rate of spirituality is evident in these two tables, which correspond when we understand that divine concern for the problems of seniors fosters their personal relationship with God.

The spiritual facet, therefore, is shown to be the most preponderant in the lives of elderly workers.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

In response to the guiding question, it was noticed that the elderly who work are mostly satisfied with the quality of the observed aspects of their lives. In particular, it was possible to notice a great adherence to religiosity, so that this is an almost absolute facet from the perspective of the participants, which is in line with the words of Araújo (1999) about the support that this area provides in facing this problem final stage of life. More specific and in-depth studies on religious life in this category can be done to gather more detailed information.

The other aspects observed also had a majority of responses recognized as satisfaction, although with greater distribution among all levels, according to the variables in the tables. It is understandable that this pre-eminence stems from the process of successful old age, in Trentini; Xavier and Fleck’s (2006) words, which also allows the permanence of the elderly in work activities (BEE, 1997).

Furthermore, the peculiar changes in the aging process mentioned by Neri (2001) were not observed in the sample group: difficulties in adapting to new functions; demotivation; need to work losses; difficulty adapting to rapid changes; psychic changes that require professional support; loss of self-image and self-esteem. Probably for the same reasons as above.

As previously mentioned, this study aimed to investigate the quality of some areas of the life of the elderly who work by using a standardized questionnaire. This material quantified the responses of the participants and made it possible to create hypotheses based on the literature consulted, however, it is possible to perceive the existence of gaps between these same responses and their causes, which makes a more rigorous critical analysis impossible. As already suggested, other more detailed studies can be carried out to qualitatively investigate these and other areas of these subjects, in the same way as a replication of this work with seniors who do not work to interweave the results of both categories: retirees and workers.

Furthermore, it is estimated that this scientific contribution can corroborate questions about the reality of the elderly who work in order to provide them with better living conditions in the aspects discussed (despite the fact that the sample group showed predominant satisfaction in the responses), as well as as in others.

REFERENCES

ALVES, Élen dos Santos; OLIVEIRA, Nathalia Alves de; TERASSI, Mariélli; LUCHESI, Bruna Moretti; PAVARINI, Sofia Cristina Iost; INOUYE, Keika. Dor e dificuldade para dormir em idosos. BrJP, São Paulo, v.2, n.3, p.217-224, 2019. Disponível em http://www.scielo.br/scielo. Acessado em 15 de janeiro. 2021. ISSN 2595-3192. https://doi.org/10.5935/2595-0118.20190039.

ABREU, A. C.; MATA, J. G. A relação do idoso com a família. In: Universidade São Judas Tadeu. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso. Núcleo de Psicologia. p.29. São Paulo, 2001.

ARAÚJO, C. D. S. F. Aspectos religiosos do idoso. In: PETROIANU, A.; PIMENTA L. G. Clínica e cirurgia geriátrica. Rio de Janeiro, Guanabara, p.8-9, 1999.

BAPTISTA, A. L. Espiritualidade na prática clínica. In: Arte Terapia Coleção Imagens da Transformação. Revista POMAR. Rio de Janeiro, n.08, v.10, p. 18-23, 2003.

BEE, Helen. O ciclo vital. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas, 1997.

BERES, V. L. G. A gente que tem o amarelão tem que se conformar: Atenção à saúde na perspectiva do idoso. In: Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo. Dissertação de mestrado, Curso de Psicologia, Núcleo de Psicologia Social – p.76. São Paulo, 1994.

BREVIGLIERI, N. M. A qualidade de vida do idoso a partir da aposentadoria. In: Universidade São Judas Tadeu. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso – Curso de Psicologia, Núcleo de Psicologia Psicodinâmica – p.83. São Paulo, 2002.

COLALTO, R. M. C. Qualidade de vida na terceira idade. In: Universidade Camilo Castelo Branco. Monografia como pré-requisito de Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso de graduação em Psicologia – p.49. São Paulo, 2002.

COUTRIM, Rosa Maria da Exaltação. Idosos Trabalhadores: perdas e ganhos nas relações intergeracionais. In: Artigo baseado na tese de doutorado – Faculdade de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas da Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, 2005. Artigo apresentado no XII Congresso Brasileiro de Sociologia realizado em 2005. Sociedade e estado, Brasília, v.21, 2, p.367-390, maio/ago, 2005.

DINIZ, L. Espiritualidade e Arte Terapia. In: Arte Terapia Coleção Imagens da Transformação. Revista POMAR. Rio de Janeiro, n.10, v.10, p.109-124, 2003.

GEIB, Lorena Teresinha Consalter; CATALDO NETO, Alfredo; WAINBERG, Ricardo; NUNES, Magda Lahorgue. Sono e envelhecimento. Revista de Psiquiatria do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, v.25, n.3, p.453-465, 2003. Disponível em http://www.scielo.br/scielo. Acessado em 15 de janeiro. 2021. ISSN 0101-8108. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0101-81082003000300007.

MARTINS, Josiane de Jesus; ALBUQUERQUE, Gelson Luiz de; NASCIMENTO, Eliane Regina Pereira do; BARRA, Daniela Couto Carvalho; SOUZA, Wanusa Graciela Amante de; PACHECO, Wladja Nara Sousa. Necessidades de educação em saúde dos cuidadores de pessoas idosas no domicílio. Texto & contexto – Enfermagem, Florianópolis, v.16, n.2, p.254-262, Junho/2007. Disponível em https://www.scielo.br/j/tce/a/PsbZSVQRtF7WkHD3vgn3Lvv/?lang=pt>. Acessado em 3 de dezembro. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-07072007000200007.

NERI, Anita Liberalesso. Desenvolvimento e envelhecimento. Campinas, Papirus (1ed.), 2001.

ORLANDO, Cássia; DIAS, João Carlos; BRASIL, Ricardo Taveiros; ARAÚJO, Tiago Coelho; BURITI, Marcelo de Almeida. Religiosidade na dimensão biopsicossocial do sujeito idoso. In: Universidade São Judas Tadeu – USJT. Artigo apresentado no XIV Simpósio Multidisciplinar da USJT realizado em 2008. São Paulo.

PANZINI, Raquel Gehrke; ROCHA, Neusa Sica da; BANDEIRA, Denise Ruschel; FLECK, Marcelo Pio de Almeida. Qualidade de Vida e Espiritualidade. Revista de Psiquiatria clínica. São Paulo. v.34, n.1, p.105-115, 2007. Disponível em http://www.scielo.br/scielo. Acessado em 28 de janeiro. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-60832007000700014.

TRENTINI, Clarissa Marceli; XAVIER, Flavio M. F.; FLECK, Marcelo Pio de Almeida. Qualidade de vida em idosos. In: PARENTE, M. A. M. P. Cognição e envelhecimento. Porto Alegre, Artmed (1ed), p.19-20, 2006.

ZIMERMAN, Guite I. Velhice: Aspectos Biopsicossociais. Porto Alegre, Artmed, 2000.

APPENDIX – FOOTNOTE

3. Brazilian Free and Informed Consent Form.

4. Brazilian Classification of Occupations.

[1] Master in Educational Sciences from the Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences of the University of Porto (FPCEUP); Master in Adult Education and Training by FPCEUP; Psychologist and Bachelor in Psychology from Universidade São Judas Tadeu (USJT).

[2] Specialist in Psychology of Sport and Physical Activity by Instituto Sedes Sapientiae. Psychologist and Bachelor in Psychology from Universidade São Judas Tadeu (USJT).

Sent: August, 2021.

Approved: November, 2021.