ORIGINAL ARTICLE

SANTOS, Edigar Bernardo dos [1], LISBOA, Julcira Maria de Mello Vianna [2]

SANTOS, Edigar Bernardo dos. LISBOA, Julcira Maria de Mello Vianna. The Incidence of The Social Security Contribution on Profit Sharing. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 06, Ed. 03, Vol. 12, pp. 125-156. March 2021. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/law/social-security-contribution

ABSTRACT

The central objective of this article is to analyze the legal relevance of workers’ participation in the profits or results (PLR) of companies in relation to the rules of incidence of social contribution on payroll and other income from work. It seeks to answer the problem question whether, in the Brazilian legal scenario, there is an incidence of the social security contribution – part company and part employee – on the funds received by workers as PLR. The starting point is the analysis of the consonance of the provisions of Law No. 10,101 of December 19, 2000, with the orderly finalistic character of the constitutional system, considering the historical origin and the legal nature of the institute and administrative and judicial jurisprudence. To this end, documentary research was carried out on websites, books and Supreme Court rulings. The research in the documents indicates that, legally, there is no possibility of incidence of the social security contribution on the amounts paid by companies to their employees as a share of profits or results provided that the requirements of the specific legislation currently in force (Law No. 10,101, of December 19, 2000).

Keywords: Profit sharing or results, incidence, social security contribution, legal nature, companies.

1. INTRODUCTION

The participation of employees in companies’ profits or results (PLR) has, for some time, become an extremely important element in terms of flexibilization of labor rights, increased competitiveness of companies and, fundamentally, integration between capital and labor, as well as as an incentive to productivity.

In Brazil, in terms of constitutional rule, the 1946 Constitution and those that followed it, including the constitution currently in force, 1988, maintained the right of workers to participate in the profits of companies. However, all of them left the realization of this right to the Legislature, which should approve ordinary, specific law, defining the applicable material criteria. Thus, it was a constitutional device of contained efficacy, without immediate applicability (BRASIL, 1946; BRASIL, 1967; BRASIL, 1988).

Considering that until 1994 the specific law had not been approved by the National Congress, the right of workers to participate in the profits and results of the company had also never been exercised. However, that year, the government issued Provisional Measure No. 794 of December 29, 1994, reissued over the course of five years, until Provisional Measure No. 1,982 of November 23, 2000, was converted into Law No. 10,101 of December 19, 2000, which had the purpose of regulating workers’ participation in the company’s profits or results (BRASIL, 1994; BRASIL, 2000).

However, it is worth noting that the study of workers’ participation in the profits or results of companies must necessarily, in addition to considering the provisions of Law No. 10,101 of December 19, 2000, based on all relevant labor, corporate and tax rules, the latter with regard to the social security contribution on payroll and the deductibility of participation in the tax results of companies.

Therefore, it seeks to define, in the Brazilian legal scenario, whether there is an incidence of the social security contribution – part of the company and part employee – on the amounts received by the workers under the rights of PLR.

To this end, to demonstrate the relevance of the theme, a brief survey was carried out on the website of the Administrative Council of Tax Appeals, using the term “PLR”, acronym for profit sharing. The first judgment found, paragraph 206-00397, dates from February 2008; doing the same research for the range from 02/2008 to 01/2012, 43[3] judgments were found; repeating the procedure for the interval from 02/2012 to 01/2016, 293[4] judgments were found; finally, applying the same procedure for the 02/2016 to 01/2020 interval, 332[5] judgments were identified. It should be highlighted that the processes deal with the collection of social security contributions on the amounts paid as PLR.

Considering the sharp increase in the number of disputes between tax authorities and taxpayers linked to the incidence of social security contribution on the PLR paid by companies to their employees, studying the matter in depth, evaluating the arguments of both parties, became extremely relevant. As for the untying of the wage budget, defined by the constitution itself, there is no divergence, as will be seen throughout this article. On the other hand, regarding the procedures established in Law No. 10,101 of December 19, 2000, there is no consensus on almost anything.

2. PROFIT SHARING AND RESULTS

2.1 BRIEF HISTORY

The purpose of promoting employee participation in corporate profits is not a recent phenomenon; there are records dating back to the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution. Thus, already in 1797, the last decade of the eighteenth century, records of a profit sharing system were identified in a glass industry in the United States. In France, the first record on the subject dates from 1812: a decree of Napoleon Bonaparte granting profit sharing to the artists of the Comédie-Française. Also in France, in 1842, the industrialist Monsieur Leclaire, when closing his balance sheet and determining profit, decided to deliver to his employees, without any explanation, a considerable portion of the result obtained in the business (FAYOL, 1989; LOBOS, 1990; SUSSEKIND, 1991).

In 1916, when problematizing the issue, analyzing the possibility of implementing employee participation in profits, Fayol (1989) stated that it was not only a seductive idea but also a possibility of agreement between capital and labor.

In terms of constitutional rule, the first registration occurred in the Political Constitution of Mexico of 1917, the inaugural landmark of social constitutionalism, which, in its art. 123, item VI, defines the institute (MÉXICO, 1917):

VI – El salario mínimo que deberá disfrutar el trabajador será el que se se suficiente, atendiendo las condiciones de cada región, para las necesidades normales de la vida del obrero, su educación y sus placeres honestos, considerándolo como jefe de familia. En toda empresa agrícola, comercial, fabril o minera, los trabajadores tendrán derecho a una participación en las utilidades, que será regulada como indica la fracción IX. (our griffin)

In Brazil, the participation of workers in the profits of companies was for the first time constitutionalized with the advent of the Federal Constitution (CF) of 1946, which, in Article 157, item IV, had: “the mandatory and direct participation of the worker in the company’s profits, in the terms and by the way the law determines” (BRASIL, 1946).

Following this, the CF of 1967, in article 158, item V, ensured the “integration of the worker in the life and development of the company, with participation in profits and, exceptionally, in management, in the cases and conditions that are established” (BRASIL, 1967). Constitutional Amendment No. 1, 1969, which for many represents a new Constitution, practically repeated, in Article 165, item V, the text of 1967.

Thus, all constitutions, as of 1946, including 1988, maintained the right of workers to participate in the profits of companies. However, all of them left the realization of this right to the National Congress, because it depended on ordinary law providing for the specific definitions applicable. For Sólon de Almeida Cunha (1997), the enforcement of this right was conditional on the publication of a law so that it would not be in the plan of the purposes. However, until the issue of Provisional Measure No. 794 of December 29, 1994, workers’ rights were never exercised.

In turn, the infraconstitutional legislation began to treat profit sharing as wage money as still in 1967. Article 621 of the Consolidation of Labor Laws (CLT), as written by Decree-Law No. 229 of February 28, 1967, created the following possibility: “The Conventions and Agreements may include among their clauses provision on the constitution and operation of joint commissions of consultation and collaboration, at the company’s level and on profit sharing.” (BRASIL, 1967).

In the same line of reasoning, in 1985, the Labor Court formed jurisprudence recognizing the participation in profits as a salary amount, which led the Superior Labor Court (TST) to the edition of the Summary of Utterance No. 251, in the same year, defining that “the share of the company’s profits, usually paid, has a salary nature for all legal purposes” (BRASIL, 1985, DJU of 13/01/86).

The lack of a specific law regulating the constitutional command and the characterization, by the Labor Court, of the participation in profits as wage money were determining factors so that the instrument was not implemented in Brazil with the amplitude that occurred after the enactment of Law No. 10,101, of December 19, 2000.

With the advent of the Federal Constitution of 1988, the institute (PLR) had already gained new contours, since the constituent, attentive to the obstacles encountered in the past, took care to expressly unlink the participation in the profits of the worker’s remuneration. In addition, it included the term “or results”, adding the “R” to the PL, which came to be called profit sharing, or PLR. Article 7(XI) of the CF/88 has the following wording:

Art. 7º These are the rights of urban and rural workers, in addition to others aimed at improving their social condition: […]

XI – participation in profits, or results, detached from remuneration, and, exceptionally, participation in the management of the company, as defined by law; (our griffin)

Unlike previous constitutional commands, 1946, 1967 and 1969, which were never regulated in the infraconstitutional scope, the provision, this time, was initially regulated by Provisional Measure No. 794 of December 29, 1994, reissued over the five years, until Provisional Measure No. 1,982 of November 23, 2000, was converted into Law No. 10,101 , of 19 December 2000.

2.2 PLR CONCEPT

There are several definitions of profit sharing and results, and its concept can vary from one country to another. Among the concepts found, stand out that of Costa (1997), for whom it is a division of part of the profits of a company in order to reward its employees, to the extent that they reach the proposed goals; and Martins (2015), for whom the employer distributes to employees the positive results, since they collaborated to obtain them. In other words, one can conceptualize profit sharing as a form of supplementary remuneration to the employee, with which a portion of the profits earned by the economic enterprise in which he participates are guaranteed.

2.3 LEGAL NATURE OF PLR

The legal nature of workers’ participation in the profits or results of companies has been the subject of major controversies in academic and legal circles. There are three divergent positions in the doctrine: one that considers profit sharing as a salary; another that argues that the legal nature stems from the articles of association; and a third that considers that profit sharing would be a kind of sui generis contract, that is, a transition between the employment contract and the company contract (NASCIMENTO, 2011).

For the proponents of the theory who considered profit sharing as salary, the legal basis was Article 457 of the CLT (caput and paragraph 1):

Art. 457. The employee’s remuneration is understood, for all legal purposes, in addition to the salary due and paid directly by the employer, as a service payoff, the tips he receives.

§ 1 – The salary includes the stipulated fixed amount, the legal bonuses and the commissions paid by the employer.

The thesis was defended, among others, by José Martins Catharino (1994), for whom, because it is the effect of an employment contract, the percentage in the profits obtained is configured as salary, the same idea defended by Délio Maranhão (1993) and, also, by Luiz José de Mesquita (apud NASCIMENTO, 2011), who sees it as part of the remuneration.

For this current of thought, profit sharing corresponds to a payback paid by the employer to the employee, characterizing a retribution that can be confused with the bonus or the percentage. Adding the usual payment, the wage nature of profit sharing would be configured (MARTINS, 2015).

This theory had great importance on the national scene until the advent of the Constitution of 1988, having been accompanied by great names of doctrine, such as the four authors mentioned above, and by the judiciary, which, at the time, came to form jurisprudence in the Superior Labor Court. However, it lost relevance with the promulgation of the 1988 Constitution, which had, in item XI of Article 7, that urban and rural workers are guaranteed participation in the profits or results of companies detached from remuneration:

Art. 7th. These are the rights of urban and rural workers, in addition to others that aim to improve their social condition: […] XI – participation in profits, or results, detached from remuneration, and, exceptionally, participation in the management of the company, as defined by law.

Paragraph 4 of art. 218 of the Constitution, which provides that “[the] law will support and encourage companies […] that practice remuneration systems that ensure the employee, unconnected with his salary, participation in the economic gains resulting from the productivity of his work […].” .

The second doctrinal chain, represented by Van Gestel and Cesarino Júnior, argued that the share of profits or results would be due to the company’s contract (company’s statute or corporate contract), the so-called affectio societatis. For this doctrinal current, which originated in the Catholic Social Doctrine, profit sharing would transform the employee into a partner of the company. Pope Pius XI, in the Encyclical Fortiean ANNO (1931), stated: “[…] in these social conditions it is preferable, where it can be mitigated the employment contracts by combining them with those of society, as has already begun to do in various ways with no small advantage of workers and employers.”, which also read that “workers and officers are considered partners in the field or in management , or share the profits.”

Also on the subject, Van Gestel (1956) advocates three possibilities for integrating the worker into the company: profit sharing, co-management and co-ownership.

In approximate reasoning, Cesarino Júnior (1965, p. 19) says that profit sharing, besides being mandatory, direct and shareholder, is the best way to solve the social issue, stating: “let us become proletarian capitalists to prevent capitalists from being made proletarians”.

However, this current does not currently have the support of important indoctrinators, such as Cunha (1997) and Martins (2015), who present, respectively, the following reasons: participation does not mischaracterize the employment contract and workers do not assume the risks of the company, as partners, nor are their shareholders.

Finally, another characteristic of the company contract that removes this theory is that, when a person is a partner of an enterprise, that is, he owns shares or shares in it, he/she must assume the risks of the enterprise. And this is the opposite of what happens to the employee, who participates only in profits, but cannot be held responsible for possible losses. Thus, the mere participation in profits does not make the employee a partner of the company, since the employment contract remains in force.

For the third current, profit sharing is a kind of sui generis contract, being a transition between the wage regime and the corporate regime, because it allows the worker a more favorable condition to enjoy the advantages of capital. They are adherents of this current Nascimento (2011), Martins (2015) and Cunha (1997).

Profit sharing, for this current, is not characterized as salary or make the employee a partner of the company, resisting the employment relationship (MARTINS, 2015). It is only a way for the worker to participate in the company by distributing the profits earned by the company with the help of the worker.

Thus, for that current, PLR is a form of transition between the employment contract and the company contract, i.e. at first sight, it has a mixed legal or sui generis nature; this is because PLR is a random provision, dependent on the existence of profit, which does not depend on the condition of partner, but rather on the existence of the employment contract, resulting from the condition of employee and the maintenance of its subordination (MARTINS, 2015).

On the other hand, PLR is a contractual figure characteristic of the modern institute of collective bargaining, since employers and employees, with the participation of the union, conclude agreements to participate in the financial result, the result of the common effort (BALERA and SIMÕES, 2014).

The best definition for the legal nature of the PLR seems to be that given by Law No. 10,101 of December 19, 2000, which, in its article 1, defines: “This Law regulates the participation of workers in the profits or results of the company as an instrument of integration between capital and work and as an incentive to productivity, in accordance with Art. 7. , item XI, of the Constitution.” (our griffin). Therefore, categorical manifestation of the legal nature of the institute.

The explanator of Provisional Measure No. 794 of December 29, 1994 (BRASIL, 1995), which was the first normative species issued to regulate Article 7, item XI, of the CF/88, clarifies that the PLR is based on:

[…] free negotiation between employers and employees, who must jointly establish the mechanisms for astoling productivity, frequency of distribution and other criteria and conditions, in search of the feasible and fair portion of the profit or results to be distributed.

After presenting the benefits to employees by the perception of a portion of the profit, the aforementioned explanamis report highlights that:

[…] the possibility of the amounts paid to workers being deducted as an expense, for the purpose of calculating the real profit, besides not constituting the basis for calculating any labor or social security charges, is a strong incentive to the employment of labor and production.

Still in the same line of reasoning, in a crystalline way, Balera and Simões (2014) say that the share of profits that employees benefit from is a “social constitutional right”.

In other words: if the profit sharing has no characteristic of salary, it also does not transform the employee into a partner of the employer. In other words, PLR is a kind of sui generis contract, being a transition between the wage regime and the corporate regime, because it allows the worker a more favorable condition to enjoy the advantages of capital. It should be added that the definition given by Article 1 of Law No. 10,101 is contained in this concept.

In summary, a substantial change in the legal nature of the PLR occurred from the 1988 Constitution, whose Article 7, item XI, expressly dislinked this portion from the remuneration. As a result, profit sharing no longer constitutes a salary in the Brazilian legal system (BRASIL, Supremo Federal Court, 2014), which is why it cannot be the basis for the incidence of the social security contribution on the salary sheet. That’s what’s going on.

2.4 NON-INCIDENCE OF SOCIAL SECURITY CONTRIBUTION ON THE PLR

In order to analyze whether there is an impact of the social security contribution on the participation of employees in the profits or results of the companies, we will take, from the outset, a comparison between Art. 195, item I, point ‘a’, and Art. 7, item XI, of the CF.

The first provision mentioned brings a tax jurisdiction to the Union to establish the social security contribution, while the second provision provides a restrictive rule of the jurisdiction assigned. The following are transcribe the texts to be compared:

Art. 195. Social security will be financed by society as a whole, directly and indirectly, in accordance with the law, through resources from the budgets of the Union, the States, the Federal District and the Municipalities, and the following social contributions:

I – the employer, the company and the entity treated as such in the form of the law, incidents on:

a) the payroll and other income from work paid or credited, in any capacity, to the individual who provides him or her service, even without employment ties; (our griffin)

Art. 7º These are the rights of urban and rural workers, in addition to others aimed at improving their social condition: […]

XI – participation in profits, or results, detached from remuneration, and, exceptionally, participation in the management of the company, as defined by law; (our griffin)

If, on the one hand, art. 195, item I, line ‘a’, attributed to the Union the competence to institute the social security contribution on the “payroll and other income from work paid or credited, in any way, to the individual who provides it, even without a bond employment ”, on the other hand, item XI of art. 7, also from the CF, expressly excluded the remunerative nature of the employees’ participation in the company’s profits or results. Comparing the two rules, it is clear that the first (art. 195) defines the legal facts that may be part of the incidence hypothesis, while the second (art. 7, item XI) excludes, also expressly, the participation of employees in the profits or results earned by the company in the field of the hypothesis of incidence of the tax under debate.

Thus, the ability to impose the referred tax cannot reach the profit sharing of the company obtained by the workers. In other words, the payment of the PLR is outside the scope of the tax jurisdiction attributed to the Union by art. 195, item I, line ‘a’, of the CF. In this same sense, Balera and Simões (2014) provide an explanatory explanation, when they say that the tax benefit that the Federal Constitution introduced on what is paid as profit sharing is an immunity rule, that is, “the immunity rule designs the taxable site, saving space where the State can affect private property ”(p.176).

Therefore, as PLR is clearly excluded from the concept of remuneration, of course, the social contribution referred to in Article 195, item I, point ‘a’ of the CF cannot take into account such PLR in the definition of the fact that generates the social security contribution, nor can the PLR integrate the quantitative characteristic of this generating fact. In other words: profit sharing or results cannot act as a technical support for taxation, and it is in a way a non-legal fact in the sense of tax law. On the other hand, it is certain that it is up to the infraconstitutional legislature to define the fact that the taxes are generating taxes, but it is also certain that this legal definition must be made in the terms illustrated by the Political Charter, and cannot disrespect the constitutional limitations to the power to tax (HARADA, 2005).

The PLR, of course, is not part of the concept of salary, nor of usual gains, that is the eventual and uncertain budget. Moreover, Art. 7, XI, of the Constitution itself assures the worker of “profit sharing, or results, detached from remuneration”. In other words, it is taken care of a law that is not confused with the remuneration for the work performed (FREIRE, 2016).

In this line of reasoning, for Balera and Simões (2014), participation is a formula of humanist capitalism and can in no way be confused with the expression “income from work” that appears in item I, paragraph a, of article 195 of CF.

In summary, the constituent legislature, pursuant to item XI of Art. 7 of the CF, with the objective of encouraging productivity and integration between capital and labor, excluded from the field of exercise of the imposed competence assumed in art. 195, item I, paragraph ‘a’, of the CF, any and all importance that may be remunerated by the company as a share in profits or results. Thus, there is no doubt about the impossibility of incidence of the social security contribution on the amounts paid by companies to their employees under the title of participation in the results.

In terms of infraconstitutional legislation, the tax jurisdiction attributed to the Union by art. 195, item I, item ‘a’, of the CF, was exercised through the command defined by item I of art. 22 of Law No. 8,212, of July 24, 1991 (BRASIL, 1991), in the following terms:

Art. 22. The contribution to the company, destined to Social Security, in addition to the provisions of Art. 23, is:

I – twenty percent of the total remuneration paid, due or credited to any security, during the month, to the insured employees and single workers who provide services to him, intended to repay the work, whatever its form, including tips, the usual gains in the form of utilities and advances arising from salary adjustment, or for the services actually provided , either for the time available to the employer or service taker, in accordance with the law or contract or, furthermore, a collective labor agreement or agreement or normative judgment. (our griffin)

On the other hand, the disconnection of the PLR from wage amounts, determined by item XI of Article 7 of the CF, was expressly recognized by Article 28, paragraph 9, paragraph ‘j’, of Law No. 8,212 of July 24, 1991, as transcribed below:

Art. 28. The salary is: […]

§9 – The contribution salary for the purposes of this Law is not exclusively:

j) participation in the company’s profits or results, when paid or credited in accordance with specific law; (our griffin)

Thus, it can be stated that item I of Article 22 of Law No. 8,212 of July 24, 1991, which defines the hypotheses of the incidence of the social security contribution on all the remuneration paid, conferred on any title, during the month, to the insured employees, all of which have the duty to be interpreted with the exclusion of the installments related to the participation in the profits or results that , in turn, once immunized by the Constitution, could never integrate the basis for calculating the social security contribution without strongly offending the constitutional text (HARADA, 2005).

Following the constitutional commandment of the final part of item XI of Article 7 of the CF, “as defined by law”, the paragraph ‘j’ of paragraph 9 of Article 28 of Law No. 8,212, of July 24, 1991, conditions the validity of the PLR institute to payment or credit in accordance with specific law.

By regulating the institute, through Law No. 10,101 of December 19, 2000, the ordinary legislature did not make the participation of employees in profits mandatory, since it did not establish a sanction for the absence of the right. The legal instrument under discussion was limited to encouraging the company to establish profit sharing by removing wage, labor and social security charges on the payment made in this respect, in addition to allowing the deductibility of participation by the competency regime, even if the payment occurs in the subsequent period (FREIRE, 2016).

In this sense, paragraph 3 of Article 3 of Law No. 10,101:

§ 3 – All payments made as a result of profit sharing plans, held spontaneously by the company, may be offset against the obligations arising from collective labor agreements or agreements related to profit sharing. (our griffin)

The legal text under discussion, Law No. 10,101, presents a visible concern to ensure that the PLR is negotiated between the parties (company and employees). In addition, it prestigious the participation of employees when determining the mandatory indirect participation by a union representative and the direct participation by a commission chosen by them, establishing the following material rules:

a. 1 – Classifies the PLR as an instrument of integration between capital and labor and as an incentive to productivity, in accordance with Art. 7, item XI, of the Constitution.

b. 2 – Determines that PLR will be the subject of negotiation between the company and its employees, through: I – joint committee; or II – collective agreement or agreement.

C. 2, paragraph 1 – Determines that, of the instruments resulting from the negotiation, there should be clear and objective rules regarding the fixing of the substantive rights of participation and adjective rules.

d. 2, paragraph 2 – Determines that the instrument of agreement concluded will be filed with the workers’ trade union.

e. 3 – Defines that PLR does not replace or supplement the remuneration due to any employee, nor constitutes a basis of incidence of any labor charge, not applying to him the principle of habituality.

f. 3, paragraph 2 – Veda anticipation or distribution of values under PLR more than twice in the same calendar year and at a daily rate of less than one calendar quarter.

g. Paragraph 3, paragraph 3 – Allows the compensation of payments made as a result of own plans with the obligations arising from collective agreements or agreements, that is, allows the coexistence of more than one plan.

It is at this point that the dispute between the Tax And Taxpayer arises: on the one hand, the State, lacking in collection, tries at any cost to mischaracterize the plans of employee participation in the results of companies; on the other hand, taxpayers, pressured by competition and high costs, see the PLR as an alternative to stimulating production at reduced costs.

In this line of reasoning, the Brazilian State, according to Balera and Simões (2014), having an exaggerated fear of fraud, ends up putting under suspicion certain schemes that house plans of this content, because it understands that they can be used to disguise certain salary adjustments.

Considering that, once the payment is characterized as a share in profits or results, there is no way to legally sustain the existence of taxation, the State, through the supervision of the Brazilian Internal Revenue Service (RFB), began to cling to the material aspects of PLR’s regulatory law. Thus, for each of the rules established by the Law, tax agents create an argument to mischaracterize the plans elaborated by taxpayers, the main ones being:

a. absence of proof of election of employees to the commission [6];

B. absence of clear and objective rules regarding the establishment of substantive participation rights and adjective rules [7];

ç. absence of prior definition of pact and goals, which are defined during the calendar year [8];

d. absence of participation by the representative union of the category [9];

e. absence of proof of the termination of the agreement with the union [10]; and

f. objective of replacing or complementing the remuneration due to employees through the paid monies [11].

Thus, a huge litigation was created: on the one hand, the Tax Authorities questions a large part of the programs that are subject to supervision; on the other hand, taxpayers are subject to very high costs to manage the dispute. Additionally, the administrative court has been deciding, in most cases, in favor of the Tax Authorities, consolidating the administrative jurisprudence in the sense that there is the incidence of the social security contribution, as will be evaluated in depth in item 6.

2.4.1 SEARCH FOR LEGISLATIVE IMPROVEMENT

Profit or result sharing, constitutionally unrelated to the remuneration paid to employees, enjoys objective tax immunity. By express constitutional objectivity, the power to institute the social contribution referred to in art. 195, item I, line ‘a’, of the CF, focusing on the amount paid by the company to the respective employees as a share of profits or results. Therefore, legally, there is no chance of the social security contribution being levied on the amounts paid by companies to their employees as profit sharing.

However, the state seeks at any cost to collect. It uses the material criteria established by Law No. 10,101 of December 19, 2000, to try to mischaracterize the participation plans adopted by companies together with their employees.

It should be emphasized that the material criteria established by Law No. 10,101, especially those determined by paragraph 1[12] of Art. 2, are very open and give scope to the interpretation by tax agents, who use this possibility to mischaracterize said plans for profit sharing or results, thus increasing the number of disputes.

On the other hand, the National Congress approved, in 2020, Law No. 14,020, of July 6, 2020, which changed some of the material requirements established by Law No. 10,101, which, in our view, aims to make the requirements of that law more objective and, thus, reduce conflicts with taxpayers. Among the changes introduced in Law No. 10,101 by the law in question, the following stand out: (i) flexibilization of the mandatory participation of the representative of the union of the respective category by allowing the commission to initiate and conclude its negotiations, if the union does not indicate its representative within a maximum of ten (10) calendar days, after being notified by the committee (amendment introduced by paragraph 10 art. 2 of the Law of 10.101); and (ii) definition of the deadline for the end of the prior negotiation, the validation of the understanding that, for the establishment of a PLR, the autonomy of the will of the contracting parties will be respected and will prevail in the interests of third parties (amendment introduced by the insertion of paragraphs 6 and 7 to art. 2 of the Law of 10.101); and (iii) clarification that non-compliance with the periodicity established in § 2 of Article 3 of Law 10.101 invalidates exclusively the payments made in disagreement with the norm (amendment introduced by the insertion of paragraph 8 to art. 2 of the Law of 10.101). Apparently, this legislative change should minimize conflicts between tax and taxpayers, since it reduced much of the spaces for subjective interpretations by supervisory agents.

Finally, the issues related to the incidence of the social security contribution regarding PLR payments have been, for a long time, the subject of endless contradictions in jurisprudence, either in the administrative or judicial sphere. This is what is being evaluated, starting with administrative jurisprudence.

2.5 CASE LAW OF THE ADMINISTRATIVE COURT – CARF

Considering the consolidation of jurisprudence in the sense that, effectively, there is no incidence of the social security contribution on the PLR, because the Magna Carta so determines, so that the amounts paid under PLR are outside the hypothesis of incidence of the social security contribution on the salary sheet, it is necessary that the programs comply with Law No. 10.101.

It should be emphasized that the discussion on the incidence of the social security contribution on the amounts paid under PLR was limited to the formal aspects of the implementation and application of the PLR program, with no discussion about the incidence of social security contribution in the hypotheses in which the PLR program meets the requirements established by Law No. 10,101. However, the rules established by the rule under discussion are quite open and, therefore, subject to various intepretações, especially that contained in Article 2, paragraph 1, of said Law, which requires “clear and objective rules regarding the fixation of substantive rights of participation and adjective rules”.

In view of this legal provision, the following question arises: these rules must be “clear and objective” in the interpretation of who – the tax agent or the taxpayer?

The payments made by companies under PLR have been frequently evaluated by the Brazilian Internal Revenue Service, which, using the vagueness of the standard, has often mischaracterized the profit sharing plans implemented by taxpayers and charged the social security contribution on the amounts paid as PLR.

At this juncture, the Administrative Council of Tax Appeals (Carf), as the administrative body responsible for the final review of the tax release, has been demanded to analyze the numerous assessments made by RFB agents and decided whether the PLR plans established by taxpayers met or not the legal requirements for the enjoyment of the hypothesis of non-incidence of the social security contribution on the respective values (KIRALYHEGY and PINTO , 2013).

Carf’s jurisprudence has been consolidated in the sense that PLR agreements need to meet the following conditions:

a. participation of employees in the negotiation of the plan, duly elected;

b. participation of a member of the union representing the category in the commissions set up to negotiate payment of PLR;

C. existence of clear and objective rules for the distribution of values;

d. filing of the agreement in the category union; and

e. payment of installments relating to profit sharing.

In summary, the understanding of the judging body is that, from reading articles 2 and 3 of Law No. 10,101, it is believed that the bases of legitimacy of a PLR plan are mainly: union intervention and employee participation in the negotiation of the plan ; existence of clear and objective rules for the values to be distributed; moment of contract archiving and periodicity of payment of installments connected to PLR (CONSELHO ADMINISTRATIVO DE RECURSOS FISCAIS. Judgment No. 2402-007.624, 4th Chamber / 2nd Ordinary Panel, Session of October 8, 2019).

In our view, the requirement of “existence of clear and objective rules for the distribution of values” becomes virtually impossible to be met, since the interpretation is the responsibility of the tax agent, and the Upper House of Tax Appeals (CSRF) has decided, in the overwhelming majority of cases, by quality vote and based only on the indictment of the tax agent, as will be seen in detail below.

Considering that, in the absence of any of the requirements described above, the court has decided by the incidence of the social security contribution on the amounts paid under PLR, as well as considering the difficulty of compliance, on the part of the taxpayer, of the requirement of “existence of clear and objective rules for distribution of values”, it was virtually impossible to obtain a decision favorable to the taxpayer in the Upper House of Tax Appeals.

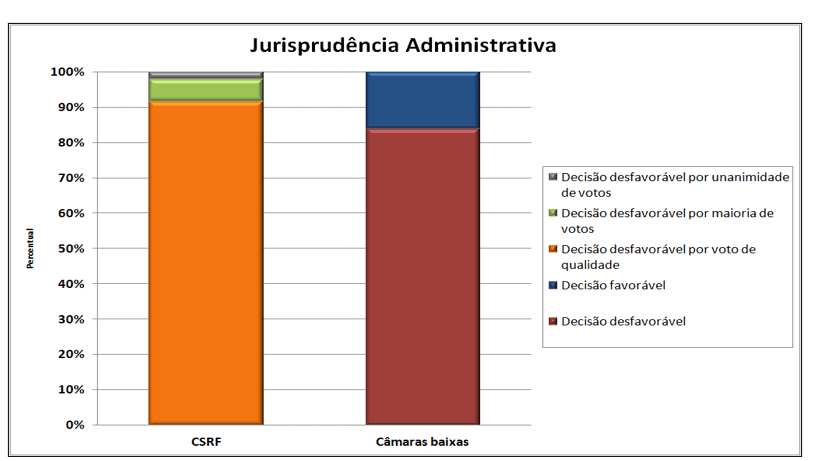

In a survey carried out on Carf’s website, using only the judgments whose theme under discussion was the PLR and taking as initial date February 1, 2019 and, as a final term, February 26, 2020, 48 CSRF judgments and 37 judgments of the trial chambers, called “low chambers”, were found. All CSRF judgments present decisions unfavorable to taxpayers, therefore, considering correct the requirement of social security contribution on the amounts paid under PLR, and of the 48 decisions, 43 were decided by quality vote, three were decided by a majority of votes and only one was decided unanimously. As for the 37 judgments at second instance, the lower chambers, 31 record decisions which were unfavourable to taxpayers and six, favourable decisions. Graph 1 summarizes administrative case law:

Figure 1 – Administrative Jurisprudence

It should be noted that these are decisions related to the taxpayers’ own programs, which pay surplus amounts to collective agreements, since these agreements, as a rule, have been accepted.

In view of this scenario, it can be concluded that the administrative jurisprudence was consolidated in order not to admit the exclusion of the social security contribution base from the amounts paid as PLR instituted by taxpayers’ own programs.

2.5.1 CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF ADMINISTRATIVE CASE LAW

The objective of this topic is to reflect on the legal reasoning of administrative court decisions unfavorable to the non-incidence of the social security contribution on the amounts paid by companies to their employees as PLR, whose judgments were identified in the research.

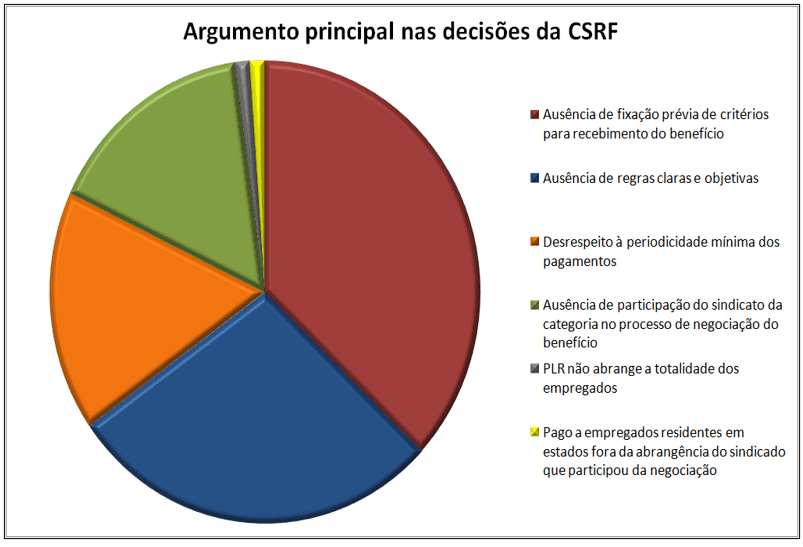

The analysis was focused on the decisions of the CSRF, as it is the last administrative instance. At the outset, it should be noted that the grounds for the votes that led to the decisions were not uniform, as out of the 48 judgments, 33 had as their main argument “the absence of previous criteria for receiving the benefit”; 25, “absence of clear and objective rules”; 15, “disregard for the minimum periodicity of payments”; 14, “absence of participation by the category union in the benefit negotiation process”; one, the main argument that “PLR does not cover all employees”; and one that the PLR was “paid to employees residing in states outside the scope of the union that participated in the negotiation”. Graph 2 summarizes the rationale for CSRF decisions:

Graph 2 – Main argument of CSRF decisions

As observed, most judgments are based on more than one argument, but the two most frequent and decisive arguments are “lack of prior setting of criteria for receiving the benefit” and “absence of clear and objective rules”. However, with regard to the second argument, “absence of clear and objective rules”, it is a criterion of enormous subjectivity, since clarity and objectivity of a rule depend on who interprets it. As the tax agent, when interpreting the standard, most of the time, has the gross intention, invariably will have the tendency to conclude that there is a lack of clarity and objectivity to such precept.

It should be clarified that, in the context of PLR programs, the rule of clarity and objectivity applies both to the definition of programs and to the definition of goals and objectives to be achieved by employees. Thus, for companies with thousands of employees working in different branches of activities, it becomes virtually impossible to define rules that do not allow someone, with the intention of disqualifying, to find some point to substantiate the lack of clarity and objectivity.

In summary, a significant portion of the CSRF’s judgments dealing with the non-incidence of the social security contribution on the amounts paid as PLR was based, in our view, on non-legal arguments, and was still decided by a vote of quality.

On the other hand, by Law No. 13,988, of April 14, 2020, art. 19-E[13] was inserted in Law No. 10,522 of July 19, 2002 (BRASIL, 2002), extinguishing the quality vote, which opens a new perspective favorable to taxpayers, since it is thus a counterpoint to the current model, in which the case law was consolidated in favor of the Tax Force by quality vote.

Finally, it remains for the judiciary to correct this deviation from the state function related to taxation. That’s what’s going on to evaluate.

2.6 JUDICIAL POSITIONING

Unlike the administrative sphere, in the judiciary there is still no consolidation of jurisprudence, but most of the decisions found in this research is in the sense that it is up to the taxpayer to prove this amount paid as plr obey the rules established by Law No. 10.101. Therefore, in order to live up to non-incidence, payments under PLR should be made in line with the rules laid down in the specific law. For both Minister Gurgel de Faria[14] and Minister Herman Benjamin[15], it was clear that Provisional Measure No. 764/1994 established the tax exemption for receipts related to profit sharing by employees, previously subject to the requirements of Law No. 10,101/2000.

In summary, the judiciary has evaluated the issues related to the incidence of social security contribution on payments under PLR only as a fática issue. That’s what’s going on to evaluate.

2.6.1 POSITIONING OF THE SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE (STJ)

As a rule, the STJ has applied Summary 7/STJ, which defines: “The claim of simple review of evidence does not appeal special”. Thus, the court has not amended the decisions of the Federal Regional Courts (TRFs). For example, excerpt from the judgment in Special Appeal 675.433/RS, of the drafting of Minister Denise Arruda [16]:

However, although such a plea must be rejected, the special action does not deserve to be upheld, since the Court of Origin held that it was not clear that the payments made actually corresponded to the participation of employees in the company’s profits.

It happens that, in order to understand this conclusion differently, it would be necessary to review the factic-probative set contained in the file, which is not feasible in a special appeal, because it bumps into the obstacle of Summary 7/STJ: “The pretension of simple review of evidence does not give special recourse.” (our griffin)

Therefore, the STJ has followed the decisions of the TRFs, whether favorable, are contrary to the non-incidence of the social security contribution. Thus, if the TRF understands that the taxpayer has proved that the payments were made in accordance with the specific legislation, determines the cancellation of the tax credit; otherwise, it determines tax enforcement.

Next, eight precedents are related in which the STJ did not know the special appeal or knew and dismissed, all with decisions of the TRFs unfavorable to the non-incidence of the social security contribution on payments under PLR. The cases were based on the application of Summary 7/STJ. The precedents are:

a. AgRg at REsp 1.108.927/SP, Rel. Minister Gurgel de Faria, DJe 12/06/2018;

b. REsp 1,574,259/RS, Rel. Min. Herman Benjamin, Second Class, DJe 5/19/2016;

C. REsp 1,452,527/RS, Rel. Minister Og Fernandes, Second Class, DJe 10/06/2015;

d. AgRg at REsp 1,516,410/RJ, Rel. Min. Humberto Martins, Second Class, DJe 05/06/2015;

e. REsp 1.180.167/RS, Rel. Min. Luiz Fux, First Class, DJe 07/06/2010;

F. AgRg at REsp 675.114/RS, Rel. Min. Humberto Martins, DJe 10/21/2008;

g. AgRg at Ag 733.398/RS, Rel. João Otávio de Noronha, DJ 25/04/2007; and

h. REsp 675.433/RS, Rel. Min. Denise Arruda, DJ 10/26/2006.

Most of the judgments listed here contain the phrase or equivalent of

[…] in the event of a special appeal, it is not feasible to verify the fulfilment of the requirements for the enjoyment of the exemption, because it is required to review matter of fact and evidence, attracting the obstacle to the knowledge of the special appeal set out in the wording of Summary 7 of the STJ: “The claim of simple review of evidence does not appeal special”.

There are, however, precedents favorable to non-incidence, such as:

a. AgRg at REsp 1561617/PE, Rel. Min. Humberto Martins, Second Class, DJe 01/12/2015; and

b. REsp 865.489/RS, Rel. Min. Luiz Fux, First Class, DJe 11/24/2010.

From the latter judgment the following excerpt is extracted: “The Special Appeal is not servile to the examination of questions that require the return of the factic-probative context of the file, in the face of the obstacle erected by Summary 07/STJ.”.

From the analysis of this sample, it is clear that the tendency of the STJ is to maintain the decisions of the TRFs, since the evaluation of evidence is carried out only up to the second degree of jurisdiction. Thus, for the taxpayer to obtain recognition of the non-incidence of the social security contribution on the amounts paid as PLR based on own programs, it is necessary that the program and the rules of investigation are able to form robust evidence. Therefore, once the judicialization has begun, it is essential that it is demonstrated, in the file, that the payments were made in accordance with the law, in order to characterize the benefit provided for in Article 7, item XI, of the CF.

In this line of reasoning, says Minister Og Fernandes (Superior Court of Justice. Special Feature 1,452,527/RS):

The Second Panel of this Superior Court has the understanding that the tax exemption on the amounts paid as a share of profits or results should occur only when the limits of the regulatory law are observed, in this case, MP no. 794/1994 and Law No. 10,101/2000.

For this reason, the jurisprudence of the STJ, considering PLR cases a fheic issue, has been consolidated in the sense that the decisions of the regional courts should prevail, since this is the last instance for the evaluation of evidence.

2.6.2 POSITIONING OF FEDERAL REGIONAL COURTS

Following the decision-making line of the STJ, the Federal Regional Courts have also based their decisions on the sense that it is up to the taxpayer to prove that the amounts paid as PLR commenacies commendated the rules established by Law No. 10.10. Therefore, in order to live up to non-incidence, payments under PLR should be made in line with the rules laid down in the specific legislation.

Excerpt from the judgment of case 0009203-87.2006.4.03.6100/SP of the TRF3 brings an argument to support a decision favorable to non-incidence: “The important thing in this subject is to verify whether the legal requirements, provided for in the legislation, were observed, because having or not having a wage nature depends exclusively on compliance with these legislative requirements.”

In cases where the decision was contrary to non-incidence, arguments such as: “the documents on the file do not comply with the requirements of Article 2, paragraph 1, of Law No. 10.101 of December 19, 2000”, or, therefore, “indispensable, therefore, that it is demonstrated, in the file, that the payments were made in accordance with the law, to characterize the benefit provided for in Article 7, item XI, of the CF, which did not occur in the hypothesis”.

In summary, in the TRFs, the vast majority of decisions have been based on the evaluation of the form of payment of profit sharing. If the court finds that the payments were made in accordance with the specific legislation, that is, Law No. 10,101, decides in favor of the non-incidence of the social security contribution; otherwise, it decides by incidence. Thus, in the evaluation of the TRFs, it is a question of proof, even in cases of assessments based on “absence of clear and objective rules”, the most controversial point of administrative jurisprudence.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Considering the arguments presented, the administrative and judicial jurisprudence, it is concluded that the best definition of the legal nature for the PLR was presented by Law No. 10,101 of December 19, 2000, which, in its article 1, defines it as an instrument of integration between capital and work and incentive to productivity, therefore, detached from the worker’s remuneration.

The rule contained in Article 7, item XI, of the Constitution is of full effectiveness in the part in which it departs the amount of participation in the company’s profits from remuneration, prohibiting the collection of the social contribution on such amounts. However, with regard to the form of participation in the company’s profits or results, this constitutional rule is of contained effectiveness, as it depends on the law for its implementation.

Jurisprudence, both administrative and judicial, has been based on the need to agree on objective, transparent and well-documented criteria on the PLR plan as a way to avoid the denaturation of the funds.

In summary, in Carf and TRFs, the vast majority of decisions have been based on the evaluation of the way profit sharing is paid. If the court finds that the payments were made in accordance with Law No. 10,101 of December 19, 2000, it decides in favor of the non-incidence of the social security contribution; otherwise, it decides by incidence. Thus, in the assessment of those courts, it is a matter of evidence.

Finally, in relation to jurisprudence, the STJ has applied Summary 7/STJ, thus following the decisions of the TRFs, whether favorable, are contrary to the non-incidence of the social security contribution.

As for Law No. 10,101, it is concluded that, by determining only that profit sharing will be the subject of negotiation between the company and its employees, in a way, brought a relaxation in labor rights, created a systematic out of state regulation, attributing to the parties the establishment of PLR programs. Paragraph 1 of the same article, when determining that, the instruments of negotiation should contain clear and objective rules created enormous legal uncertainty, enabling the Tax Authorities, by personal interpretation of the supervisory agents, to mischaracterize the plans implemented by the companies and make assessments with the imposition of the collection of the social security contribution.

National Congress approved Law No. 14,020, amending some of the material requirements established by Law No. 10,101, of December 19, 2000, by inserting paragraphs 5 to 10 to art. 2 of the PLR Regulatory Law, the requirements of said law have become more objective, which should reduce conflicts between tax authorities and taxpayers.

With regard to administrative jurisprudence, although by quality vote, it is concluded that it is consolidated, in the sense that the social security contribution is due on the amounts paid under PLR, which was confirmed by the research conducted on Carf’s website, recognizing the validity of the collection of the social security contribution on amounts paid under PLR.

On the other hand, Law No. 13,988 of April 14, 2020, article 19-E[17] was inserted in Law No. 10,522 of July 19, 2002 (BRASIL, 2002), extinguishing the quality vote, which opened a new perspective for taxpayers, since most of the judgments that consolidated the case law in favor of the Tax Office were decided by a quality vote.

In short, legally, there is no possibility of incidence of the social security contribution on the amounts paid by companies to their employees as a profit share provided that the requirements of the specific legislation currently in force are met (Law No. 10,101, of December 19, 2000). In other sayings: the amounts paid under PLR will not suffer the incidence of social security contributions only if they are credited in accordance with the provisions of this Law, with regard to their formal and material requirements.

REFERENCES

BALERA, Wagner; SIMÕES, Thiago Taborda. Participação nos lucros e nos resultados: natureza jurídica e incidência previdenciária. São Paulo: Revista dos Tribunais, FISCOSoft, 2014.

BRASIL. CONGRESSO NACIONAL. Exposição de Motivos da Medida Provisória nº 794/1994. Diário do Congresso Nacional, 19 jan. 1995, p. 295. Disponível em: <http://imagem.camara.gov.br/dc_20.asp?selCodColecaoCsv=J&Datain=19/01/1995&txpagina=409&altura=700&largura=800#/>. Acesso em: 23abr.2020.

BRASIL. CONSELHO ADMINISTRATIVO DE RECURSOS FISCAIS. Vários Acórdãos. Disponíveis em: <http://carf.fazenda.gov.br/sincon/ public/ pages/ Consultar Jurisprudencia/ consultarJurisprudenciaCarf.jsf>. Acesso em: fev. 2020.

BRASIL. Consolidação das Leis Trabalhistas (1943). Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/decreto-lei/del5452.htm>. Acesso em: 8 jan. 2020.

BRASIL. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil (1967). Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao67.htm>. Acesso em: 8 jan. 2020.

BRASIL. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil (1988). Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/Constituicao/ConstituicaoCompilado.htm>. Acesso em: 25 nov. 2019.

BRASIL. Constituição dos Estados Unidos do Brasil (1946). Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicao46.htm>. Acesso em: 8jan2020.

BRASIL. Lei nº 10.101, de 19 de dezembro de 2000. Dispõe sobre a participação dos trabalhadores nos lucros ou resultados da empresa e dá outras providências. Disponível em: <https://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/l10101.htm>. Acesso em: 19abr2020.

BRASIL. Lei nº 10.522, de 19 de julho de 2002. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/2002/l10522.htm#:~:text=LEI%20No%2010.522%2C%20DE%2019%20DE%20JULHO%20DE%202002.&text=Disp%C3%B5e%20sobre%20o%20Cadastro%20Informativo,Art.>. Acesso em: 8jun2020.

BRASIL. Lei nº 8.212, de 24 de julho de 1991. Dispõe sobre a organização da Seguridade Social, institui Plano de Custeio e dá outras providências. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/L8212cons.htm>. Acesso em: 19abr2020.

BRASIL. Medida Provisória nº 794, de 29 de dezembro de 1994. Disponível em: <http://legislacao.planalto.gov.br/legisla/legislacao.nsf/Viw_Identificacao/mpv%20794-1994?OpenDocument>. Acesso em: 19abr2020.

BRASIL. Medida Provisória nº 905, de 11 de novembro de 2019. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2019-2022/2019/Mpv/mpv905.htm#:~:text= MEDIDA%20PROVIS%C3%93RIA%20N%C2%BA%20905%2C%20DE%2011%20DE%20NOVEMBRO%20DE%202019&text=Institui%20o%20Contrato%20de%20Trabalho,trabalhista%2C%20e%20d%C3%A1%20outras%20provid%C3%AAncias.>. Acesso em: 16mai2020.

BRASIL. Medida Provisória nº 955, de 20 de abril de 2020. Disponível em: <http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/_ato2019-2022/2020/Mpv/mpv955.htm.>. Acesso em: 16mai2020.

BRASIL. SUPERIOR TRIBUNAL DE JUSTIÇA (decisão monocrática). Agravo em Recurso Especial 1.108.927/SP (2017/0124226-7). Agravante: Arch Química Brasil Ltda. Agravada: Fazenda Nacional. Relator: Ministro Gurgel de Faria. Disponível em: <https://ww2.stj.jus.br/ processo/dj/documento/mediado/ ?componente=MON&sequencial=84439894&tipo_documento=documento&num_registro=201701242267&data=20180802&formato=PDF>. Acesso em: 15mar2020.

BRASIL. SUPERIOR TRIBUNAL DE JUSTIÇA. Consulta processual. Disponível em: <https://ww2.stj.jus.br/processo/pesquisa/?aplicacao=processos.ea>. Acesso em: 23mar2020.

BRASIL. SUPERIOR TRIBUNAL DE JUSTIÇA. Recurso Especial 1.452.527/RS. Relator: Min. Og Fernandes. Disponível em: https://ww2.stj.jus.br/processo/ revista/documento/ mediado/?componente=ITA&sequencial=1367805& num_ registro= 201401050846&data =20150610&formato=PDF>. Acesso em: 29mar2020.

BRASIL. SUPERIOR TRIBUNAL DE JUSTIÇA. Recurso Especial 1.574.259/RS (2015/0314561- 3). Relator: Ministro Herman Benjamin. Disponível em: <https://ww2.stj.jus.br/ processo/pesquisa/>. Acesso em: 15mar2020.

BRASIL. SUPERIOR TRIBUNAL DE JUSTIÇA. Recurso Especial 675.433/RS. Relatora: Ministra Denise Arruda. Disponível em: <https://ww2.stj.jus.br/processo /revista/documento/ mediado/?componente=ITA &sequencial=652886& num_ registro=200401135984&data=2006102>. Acesso em: 23mar2020.

BRASIL. SUPREMO TRIBUNAL FEDERAL (Pleno, voto vencido). Recurso Extraordinário 569.441/RS. Recorrente: Instituto Nacional do Seguro Social – INSS. Recorrida: Maiojama Participações Ltda. Relator: Min. Dias Toffoli, 30 de outubro de 2014. Disponível em: <http://redir.stf.jus.br/paginadorpub/paginador .jsp?doc TP= TP&docID=7708707>. Acesso em: 2mar2020.

BRASIL. TRIBUNAL REGIONAL FEDERAL DA 3ª REGIÃO. Vários Acórdãos. Disponíveis em: <http://web.trf3.jus.br/consultas/Internet/ConsultaProcessual>. Acesso em: 30jan2020.

BRASIL. TRIBUNAL SUPERIOR DO TRABALHO. Súmula nº 251 (1985). Disponível em: <https://www3.tst.jus.br/jurisprudencia/Sumulas_com_indice/Sumulas_Ind_ 251_ 300.html#SUM-251>. Acesso em: 14dez2020.

CATHARINO, José Martins. Tratado jurídico do salário. São Paulo: LTr, 1994.

CESARINO JÚNIOR, Antônio Ferreira. A verdadeira participação nos lucros. Revista de Administração de Empresas. Disponível em: <https:// www.scielo.br/scielo.php? pid=S0034-75901965000100001&script=s ci_arttext#7b> Acesso em: em 6dez2020.

COSTA, Sérgio Amad. A prática das novas relações trabalhistas. São Paulo: Atlas, 1997.

CUNHA, Sólon de Almeida. Da participação dos trabalhadores nos lucros ou resultados da empresa. São Paulo: Saraiva, 1997.

FAYOL, Henri. Administração industrial e geral. 9 ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 1989.

FREIRE, Elias Sampaio. Abrangência da base de cálculo das contribuições previdenciárias: folha de salários e demais rendimentos do trabalho pagos ou creditados, a qualquer título, à pessoa física. 266 f. 2016. Dissertação (Mestrado) – Centro Universitário de Brasília. Programa de Mestrado em Direito. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Jefferson Carús Guedes. Disponível em: <http://bdtd. ibict. br/vufind/ Record/CEUB_677e1153fa49d30e8fe0e7cfde665f4d>. Acesso em: 24jan2020.

HARADA, Kiyoshi. Participação nos lucros ou resultados. Sua natureza jurídica. 2005. Disponível em: <http://investidura.com.br/biblioteca-juridica/artigos/direito-trabalho/3331-participacao-nos-lucros-ou-resultados-sua-natureza-juridica>. Acesso em: 24 jan. 2020.

KIRALYHEGY, Eduardo Botelho; PINTO, Rafael Augusto. Posicionamento do Carf acerca da incidência da contribuição previdenciária sobre participação nos lucros ou resultados das sociedades. International Standard. 2013. ISSN 2357-9293. Disponível em: <www.abdf.com.br/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id= 272:posicionamento-do-carf-acerca-da-incidencia-da-contribuicao-previdencia>. Acesso em: 1fev2020.

LOBOS, Júlio. Participação dos trabalhadores nos lucros das empresas. São Paulo: Hamburg, 1990.

MARTINS, Sérgio Pinto. Participação dos Empregados nos Lucros das Empresas. 4 ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 2015.

MÉXICO. Constitución Política de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (1917). Disponível em: <http://www.diputados.gob.mx/LeyesBiblio/ref/cpeum/CPEUM_ orig_ 05feb1917_ima.pdf>. Acesso em: 10jan2020.

NASCIMENTO, Amauri Mascaro. Curso de Direito do Trabalho. 26 ed. São Paulo: Saraiva, 2011.

PAPA PIO XI, Encíclica Quadragésimo ANNO (1931). Disponível em: <http://www.vatican.va/content/pius-xi/pt/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xi_enc_ 19310515_ quadragesimo-anno.html>. Acesso em: 6dez2020.

SUSSEKIND, Arnaldo. Instituições de direito do trabalho. 12 ed. São Paulo: LTr, v. 1, 1991.

VAN GESTEL, C. A Igreja e a Questão Social. Rio de Janeiro: Agir, 1956.

APPENDIX – FOOTNOTE REFERENCE

3. Search: Camaras/Turmas (all). Start date (01/02/2008); final date (31/01/2012). Menu contains (PLR). Judgments Found: 43.

4. Search: Camaras/Turmas (all). Start date (01/02/2012); final date (31/01/2016). Menu contains (PLR). Judgments Found: 293.

5. Search: Camaras/Turmas (all). Start date (01/02/2016); final date (31/01/2020). Menu contains (PLR). Judgments Found: 332.

6. Arguments identified in 9202-007,481, 9202-008,338 and 9202-008.457. Phrases such as “The Variable Compensation Models 2009, 2010 and 2011 issued by the Human Resources Board do not demonstrate the participation of employees in their preparation”. Or “as well as the formation of the “commission” recommended in article 2 i of Law 10.101/2000 was not evidenced”

7. Arguments identified in 9202-008,457, 9202-007,478, 9202-007,478, 9202-007,481, 9202-008,404, 9202-008,355, 9202-008,187, 9202-008,041, 2201-005,314, 9202-007.942, 2201-005,205, 2201-005.160, 9202-007,873, 9202-007,698, 9202-007,610, 9202-007,474 and 9202-007,364.

8. Arguments identified in judgments No 9202-008.319, 9202-008.248, 9202-007,478, 9202-007.481, 9202-007.287, 9202-008.187, 9202-008.185, 9202-008.088, 9202-008.045, 9202-008.041, 9202-008,046, 9202-007,942, 9202-007,938, 9202-007,873 and 9202-007,609.

9. Arguments identified in 9202-008.457, 9202-007.481, 9202-008.318, 9202-008.338, 9202-008.355, 9202-008.331, 9202-008.187, 9202-008.178, 9202-008,088, 9202-007,942, 9202-007,939, 9202-007,364 and 9202-007,366.

10. Arguments identified in judgments no. 2302-003.550, 2401-004.365 and 2401004.796.

11. Arguments identified in 9202-008.457, 9202-007.362, 9202-008.404 and 9202-007.481.

12. “Art. 2º (…), § 1 – The instruments arising from the negotiation shall contain clear and objective rules regarding the fixing of the substantive rights of participation and adjective rules, including mechanisms for the measurement of information pertaining to compliance with the agreement, periodicity of distribution, period of validity and deadlines for review of the agreement, and may be considered, among others, the following criteria and conditions: I – productivity indices , quality or profitability of the company; II – programs of goals, results and deadlines, agreed in advance.”

13. Art. 19-E. “In the event of a tie in the judgment of the administrative process of determination and requirement of the tax credit, the quality vote referred to in § 9 of Art. 25 of Decree No. 70,235 of March 6, 1972, does not apply, resolved favorably to the taxpayer.”

14. Superior Court of Justice, monocratic decision. Special Appeal Injury 1,108,927/SP (2017/0124226-7). Aggravating factor: Arch Química Brasil Ltda.

15. Superior Court of Justice. Special Feature 1.574.259/RS.

16. Superior Court of Justice. Special Feature 675.433/RS.

17.”Art. 19-E. In the event of a tie in the judgment of the administrative process of determination and requirement of the tax credit, the quality vote referred to in § 9 of Article 25 of Decree No. 70,235 of March 6, 1972, does not apply, resolving favorably to the taxpayer.”

[1] Master’s degree in Constitutional and Tax Procedural Law from the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo (PUC-SP). Master’s degree in Accounting From PUC-SP. MBA in Tax Law from fundação Getúlio Vargas de São Paulo (FGV-SP). Specialist in Accounting and Finance at the Foundation Institute of Accounting, Actuarial and Financial Research (FIPECAF). Specialist in Tax Law by Damásio. lawyer.

[2] Guidance counselor. PhD in Tax Law from the Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo (PUC-SP). Professor of Tax Law in undergraduate and graduate courses at PUC-SP. Deputy Coordinator of the Law Course at PUC-SP. Coordinator of the Tax Law Chair with Department IV – Tax, Economic and Commercial Relations of the Law School of PUC-SP. Judge Taxpayer of the Court of Taxes and Fees of the State of São Paulo (TIT). lawyer.

Submitted: March, 2021.

Approved: March, 2021.