NASCIMENTO, Helder José Souza do [2]

MORAES, Francisco dos Santos [3]

PUTRICK, Simone Cristina [4]

DENDASCK, Carla Viana [5]

NASCIMENTO, Helder José Souza do; et.al. Heritage Fair BR: Experiences and Narratives Supported in Patrimonial Education for Musealization of a Territory for Development. Multidisciplinary Scientific Journal. Edition 08. Year 02, Vol. 02. pp. 37-52, November 2017. ISSN:2448-0959

summary

The present work seeks to present reflections on the potential of the BR Patrimony Fair, held in the city of Parnaíba, State of Piauí, in the Mid North region of Brazil. Within this space, we seek to take into account the importance of the contextualization and practices of Patrimonial Education and its contribution to an education of the senses. But studies also revolve around thinking about the musealization of cultural heritage as a strategic process for the development of the city and region, marked by the presence of a Delta, unique in the Americas to the open water, mangroves, rivers, festivals, forms of expression that constitute marks of identity and memory for the peoples of the Delta.

Keywords: Heritage, Patrimonial Education, Museum.

Introduction

In the first stage to introduce the subject, it will be pertinent to situate the scenario in which the BR Heritage Fair is born and the context in which the event is inserted, conceived as a strategic tool for the development of a territory and its inhabitants, supported in the bases of sociomuseology or ‘new museology[6]‘, if that’s what we can call it. Parnaíba, a Piauían city with a Historic Site Tombado as Brazilian National Patrimony, since 2008, is part of a territory that carries in its essence singular cultural manifestations and which is indissociably rich in material and immaterial patrimony, reflected in the bumba-meu-boi, in cattle farms , in the colonial mansions and on the railway, in the popular tradition of religious processions and in the marujada, bobbin lace and embroidery, handicrafts of red clay and carnauba – tree of life, artisanal fishing, rivers, ponds, in the only Delta to flow into the open ocean of the Americas. Manoel de Barros tells us[7] in one of his poems, “that the importance of a thing is not measured with a tape measure, with scales or barometers, and so on. That the importance of a thing is to be measured by the enchantment that the thing produces in us. ” But nevertheless, so much expression and richness as is often mentioned, of the city and territory presented, which can never be measured and translated, other than that of the face-to-face that affects real experience, has not yet been sufficient in itself for the education of the senses of the community for the preservation of their cultural assets, many threatened or even replaced by a gap never filled.

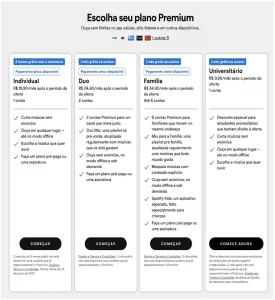

It is in front of this scenario that the BR Patrimony Fair is born in 2016, under the baton of the Postgraduate Program in Ar[8]ts, Heritage and Museology of the Federal University of Piauí – UFPI, Campus Parnaíba. A cultural, educational and social initiative that will take as a reference events similar to those that have already occurred successfully in Portugal, Spain, Italy, Germany and more recently in countries in Africa. The proposal, based on Social Museology, was thought together with local actors as a way to strengthen the heritage dimension by inspiring new possibilities and achievements for local development through an educational and cultural process of identifying daily practices, customs, beliefs and historical experiences , in order to preserve them and at the same time to dynamize them with connections between spaces / practices and the present time, stimulating the discovery of new uses, carried by the idea that the patrimony is not separated from the daily life.

This study presents contemporary museological reflections, believing in the implantation of a new pattern of musealization, emerging mainly since the Mesa de Santiago de Chile (1972), a statement that questions the classical model – Museum of Observation, Museum of Data -, and adopts a new form – Open and Interactive Museum – that supposes the participation of the community in the process of recognition, management and protection of the patrimony. It is exactly this last model that the Heritage Fair BR hosted by the Master in Arts, Heritage and Museology, proposes for the city of Parnaíba and the territory inhabited by the deltaic populations, believing that an open-air museum like the one we are presenting today can not be closed on only four walls. Since, more than a building with collections to be enjoyed by visitors, we are holders of a territory rich in cultural and natural heritage, which must be in place for the development of the community itself and beyond. Throughout the study we will approach the conceptual analysis of some words, terms and expressions inherent in the interdisciplinary approach that allows the reflection of the role and the place of heritage education in this process? And as objects of the investigation itself we can find subsidies to answer: What education is this that we need? What heritage is this that we have?

To this end, we will take as a basis the experiences and narratives observed and absorbed along the path of idealization, production and execution of the Patrimony Fair, particularly the analysis of the Conference’s speech presented at a parallel event at the International Congress on Arts, Heritage and Museology , By the Coordinator of Patrimonial Education of the National Historical and Artistic Patrimony Institute (IPHAN), Sônia Rampim Florêncio, in a movement to unveil horizons on good practices focused on “Heritage education and social participation: participatory inventories”, ratifying the ideals proposed in the case of Parnaíba and the APA of its Delta. We also believe that in addition to the study of museological concepts, we can disseminate this state of revolution and break paradigms in the way of thinking about local heritage, introduced with the arrival of the Master in Arts, Heritage and Museology in the city of Parnaíba in 2015 to that the concept of a museum can be disseminated in the service of the community’s development needs, inaugurating a new era of democracy and cultural citizenship.

The place and event: A necessary correlation

Under the sunshine of the equator and bathed by the Atlantic Ocean, the city of Parnaíba is located in the northern part of the state of Piauí, considered the gateway to the Parnaíba Delta, a popularly named title for the Environmental Protection Area (APA) created by the Presidential Decree on August 28, 1996, with a coverage area of 2,750 km² – and has the best infrastructure among the municipalities that make up this geographic formation of the river with the sea, unique in the Americas, a biodiverse unit composed of mangroves, beaches, restingas, fixed and mobile dunes, fluvial-marine and lacustrine plains, caatinga and carnaubal areas. In addition to the coastal zone of the city of Parnaíba the Delta is also located in the cities of Cajueiro da Praia, Luis Correia and Ilha Grande, in Piauí; Araioses, Agua Dulce, Tutóia and Paulino Neves, in Maranhão; Chaval and Barroquinha, in Ceará.

In order to understand the importance of this area in the global context, APA is conceived as a type of conservation unit defined by Federal Law 6,902 of April 27, 1981, an instrument by which the executive branch established that, when there is a relevant public interest, declare an area of national territory of interest for environmental protection in order to ensure the well being of human populations and to conserve or improve local ecological conditions.

Among the points shared by the municipalities of the Delta is the commercial vocation of the Coastal Zones, as a gateway to the pre-Amazon hinterland and to the hinterland of the backlands. Another common point is the tradition of artisanal fishing, resulting from conditions favored by the ecosystem. And, finally, the tourist and ecological vocation determined by the rich potential of the entire coastal strip that makes up the Parnaíba Delta (APA of the Parnaíba Delta, Geological and Economic Socioeconomic Management and Diagnosis Plan, p.42)[9]

Due to the landscape, the production and generation of income are very much related to the characteristics of the environment, to extractivism and tourist exploitation. Parnaíba stands out in this context because it has a population almost eminently urban that contributes to the commercial activity, the exportation of vegetal resources, especially carnauba wax, babassu oil, coconut fat, jaborandi leaf, cashew nut, acerola , cotton and leather. The city is also nowadays a strategic educational center of Basic Education, Higher Education and Post-graduation Lato and Stricto Sensu. It is the second largest and richest in the state of Piauí, with GDP just behind the capital, Teresina (IBGE 2014).

The name of the municipality “Parnaíba” occurred because of the nomenclature of the river, – born in the Chapada das Mangabeiras, extreme south of Maranhão -, which because of its importance is the denominator of the whole Delta. Witnessing the process of colonization of Brazil, meandered by the Igaraçu River and anchored in one of its main postcards, the “Porto das Barcas”, Parnaíba, rises from the middle of the second half of the eighteenth century within an architectural plurality with Portuguese influences, English to the art deco of the emblematic concepts of his house. In its urban trajectory it keeps memories of three centuries conserving still great part of its material patrimony. High the city category in 1844, it had important economic cycles with the charque, the leather and the carnaúba. In 2008, Parnaíba became legally protected by Federal Tombamento, proposed by the National Historical and Artistic Heritage Institute (IPHAN), and became the National Patrimony.

In this tunnel, even with more than twenty years of legalization of the Delta APA and almost ten years of federal tipping, there is still no reflective attitude towards the concept “Parnaíba – Heritage City”. It is latent the absence of this identity by part of the population that uses the self-esteem that these titles should generate. This problem denotes the absence of actions that create ties of technical cooperation between public and private agents and the resident community; and that there is no homogeneous perception of the urgency of protecting the rich and complex cultural heritage.

In the midst of these anxieties coming from actors from several matrices, members of this community interested in improving the quality of life and human condition of the indigenous people who are also patrimony and linking it with concrete life, we believe in an instrument of systematizations of historical experiences that integrate parceled knowledge into dynamic structures, the fruit of a dialectical and participatory process, without certain monologues, but of a creative and emancipatory dialogue; hence we propose the “Heritage Fair BR”, based on principles and strategies of Heritage Education.

Heritage Fair BR: Perspectives and reflections on the participatory process

As teachers and students of the Professional Master in Arts, Heritage and Museology of the Federal University of Piauí – UFPI, Campus Parnaíba, we launched a necessary crusade in debating the role of institutions and museum actions in the city of Parnaíba during the accomplishment of the National Week of Museums, which is a cultural season coordinated by the Brazilian Institute of Museums – IBRAM, which takes place annually in celebration of International Museum Day (May 18). Each year, the Icom (International Council of Museums) launches a different theme for the celebration of that date, which is also the guiding motto of the activities of the Museum Week.

With the BR Heritage Fair, a pioneering proposal in Piauí and Brazil, held during the Museum Week in Parnaíba, we hope to promote cultural and environmental heritage and create a culture of consumption of cultural goods in a perspective that values the economic and social, cultural factors, education, tourism, income generators and employment and income developers. The Heritage Fair has materialized in a set of actions of an educational nature, which enables us to dialogue with a larger part of society, public and private agents, companies, architecture / design offices, tour operators, territorial base projects, conservation and restoration and urban rehabilitation, other universities and specialized training centers, artists, artisans, all those interested in matters related to heritage, museums, tourism, entrepreneurship and development.

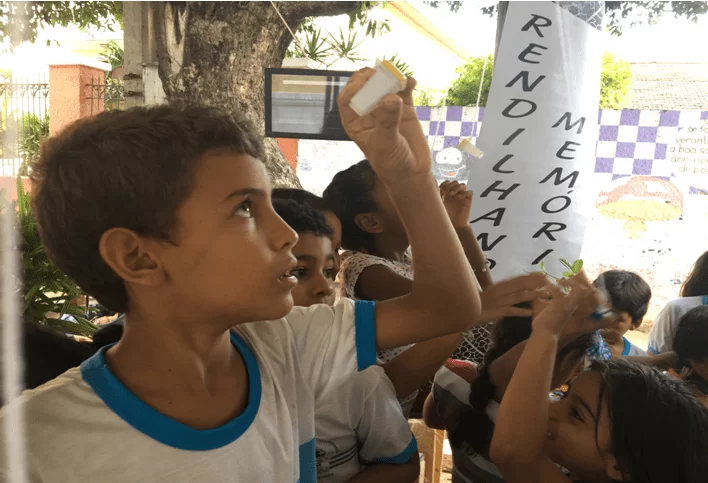

The ‘fair’ format was designed to remove this discussion of the strictly academic universe and to establish a closer connection with the citizens that integrate the cultural landscape of that territory, in an attempt to demystify the complexities of understanding about the recent actions of the world of the patrimony and museums This work of leaving beyond the walls of the academy allows to place in the same level and space, sociologists, fishermen, professors of career, embroiderers, doctors and semi-alphabetized, understanding each one like lord of its office and active member of the community. It is these multiple voices with which we will work, since heritage education does not disregard or disqualify any of the actors interested in the cultural assets of their localities, a method expressed by Carlos Rodrigues Brandão in the article “Participatory research: a moment of popular education.” Like this:

In most cases, participant research is a time of popular education work carried out with and at the service of popular communities, groups, and social movements. It is from the constant non-doctrinal dialogue on the part of the party that a consensus that is always dynamic and modifiable must also be built. A true participant research creates solidarity, but never imposes knowledge and values (BRANDÃO, Ver. Ed. Popular, Uberlândia, v. 6, p-55, jan./dez. 2007)

Through “come and eat”, music, exhibitions, live workshops of the arts associated with the cultural landscape of the Middle North, we will hold a series of conferences, lectures, thematic tables, conversation wheels, coordinated communications about museums and their social function, in a space that pretends to be charming, playful, colorful and diverse, characteristic of the free fairs since the medieval age.

We know that the Heritage Fair is only one of the possible educational interventions to produce an accumulation of training and information capable of promoting this self-reflection in the community about the importance of its cultural assets, however, we believe that such a tool is strategic to accommodate the heterogeneity of which will naturally come to this process of education.

Patrimonial Education: a trajectory

By assuming the BR Heritage Fair as a potential instrument for understanding the fundamental and pedagogical role of identifying, recording and safeguarding heritage in the process of musealization of a territory, we must understand what heritage we are talking about. As a relevant reference in the conceptualization of this patrimony, the Brazilian Constitution of 1988,

Art. 216. The assets of a material and immaterial nature, taken individually or together, bear a reference to the identity, action, and memory of the different formative groups of Brazilian society, which include:

I – the forms of expression;

II – the ways of creating, doing and living;

III – scientific, artistic and technological creations;

IV – works, objects, documents, buildings and other spaces destined to artistic-cultural manifestations;

V – urban complexes and sites of historical, landscape, artistic, archaeological, paleontological, ecological and scientific value. (Federal Constitution of 1988)

In this transcription of the Constitution, we can define that heritage is first and foremost man himself, what surrounds him and all his production, coming from the different formative groups of Brazilian society, which makes the concept broader, enabling the individual to make a reading the world, understanding the socio-cultural universe in which it is inserted and having an active awareness for the construction of its present and future, an inseparable relation to the teaching / learning process. Hence lies the indispensable relation between museum and education.

It is the formation of citizens aware of their identity and memory that can make an ecomuseum,[10] such as those intended in the territory of the Delta, contribute to the appreciation of cultural references, meanings and practices of social life (festivals, forms of expression, etc.).

“Heritage education is constituted of all formal and non-formal educational processes that focus on socially appropriate cultural heritage as a resource for the socio-historical understanding of cultural references in all its manifestations.”

“Educational processes should be based on the collective and democratic construction of knowledge, through permanent dialogue between cultural agents and the effective participation of communities holding and producing cultural references, where various notions of Heritage coexist.”

IPHAN. Patrimonial Education: history, concepts and processes. Brasília: Institute of National Historical and Artistic Heritage, 2014., P. 19

This theme of heritage education is not so recent in Brazil, and in the thirty years of actions in this sense permeate the activities of the National Historical and Artistic Heritage Institute (IPHAN), which is responsible for the formation of the idea of heritage in Brazil. one of its fronts of action, although it still does not receive this name. It is “from the 1st Seminar held in 1983 at the Imperial Museum in Petrópolis, RJ, inspired by the pedagogical work developed in England under the name of Heritage Education”, as the Basic Guide to Heritage Education (HORTA et al. , 1999), that expression has become part of our vocabulary, but has undergone transformations over time, as well as the very concept of patrimony within the organ of protection. Sônia Rampin FLORÊNCIO (2014)[11], points out that already in the draft of the creation of the SPHAN (current IPHAN), Mário de Andrade demonstrates the interest in promoting educational actions by the organ, period from 1937-1970: identified by the spirit of ” to preserve”; the period from 1970-1983: it is characterized by the premises of participation, development, when from the ideas of Aloísio Magalhães, IPHAN’s president at the time, the Interaction Project is created, which proposes a greater relation in educational work with the dynamics of cultural daily life; It was only in the period 1983-2004 that the concept of “Patrimonial Education” was created as a methodology, more precisely in 1999 when the Basic Guide to Heritage Education was published, which intends to establish a work methodology based on “cultural literacy “.

And among these important milestones that reveal the trajectory of patrimonial education in IPHAN, is the Charter of New Olinda (2009), I National Forum of Cultural Heritage (2009), Document of the II National Meeting of Patrimonial Education (2011), publication “Patrimonial Education: history, concepts and processes” (2014); “Patrimonial education: participatory inventories” (2016); and more recently, Ordinance 137 of April 2016, which in its Art. 3º establishes important guidelines of Patrimonial Education:

I – Encourage social participation in the formulation, implementation and execution of educational actions, in order to stimulate the protagonism of the different social groups;

II – Integrate educational practices into daily life, associating cultural assets with people’s living spaces;

III – to value the territory as an educational space, susceptible of reading and interpretations through multiple educational strategies;

IV – To favor the relations of affection and esteem inherent to the valuation and preservation of the cultural patrimony;

V – Consider that educational practices and preservation policies are inserted in a field of conflict and negotiation between different segments, sectors and social groups;

VI – To consider the intersectoriality of educational actions, in order to promote articulations of the policies of preservation and valorization of cultural heritage with those of culture, tourism, environment, education, health, urban development and other related areas;

VII – encourage the association of cultural heritage policies with local, regional and national sustainability actions;

VIII – consider cultural heritage as a transversal and interdisciplinary theme.

These guidelines are related to a series of conceptual premises that help to problematize the construction of our knowledge about education that we should consider for a really transformative action, contrary to what Paulo Freire calls a “banking” education, mer[12]ely instructive, that takes the community as an information consumer rather than accepting it with its differences, subjectivities, pluralities, in which people are agents of development.

From a socio-constructivist perspective, it is necessary to think of a Patrimonial Education of mediation for the appropriation of knowledge, which looks at the community as a producer of knowledge, considering their experiences and recognizing the existence of local knowledge associated with the memory of the place and the people who are holders of the “good.” A two-way process as Freire says, “No one educates anyone, no one educates himself; men are educated in communion, mediated by the world. ”

We must break conceptual paradigms by expanding the concept that “Heritage is everything we create, value and want to preserve: monuments and works of art, as well as parties, songs and dances, revelry and food, knowledge, do and talk. All at once we produce with our hands, ideas and fantasy (FONSECA, 2005, p. 21), “everything that expresses the different cultural contexts in which we live, all educational contexts. In order to reduce the chasm that separates erudite culture from popular culture, as if it were in a hierarchy inferior to the first.

Following the idea of Aloísio Magalhães, that “The community is the best guardian of its patrimony”, we must consider the effective participation of the communities in the recognition of the patrimony and in the elaboration and implementation of educational actions. That is, there must be legitimation of the whole process by those who experience the patrimony and not only by a group of intellectuals. Thus, it is important to think that all the legal frameworks and guidelines created in the time frame with a focus on heritage education can not adopt vertical movement, from top to bottom, as a regulation emanating from the power of the state, but rather serve as an orientation that helps in the path of actions.

At all times the guidelines presented here reaffirm the idea that patrimony as a resource for local development can not be seen outside the rhythms of society, since cultural assets are fully inserted in the spaces of life among all conflicts and tensions. It is clear that this understanding of cultural heritage as a field of conflict also serves to stimulate solidarity in accepting the different. And in this aspect heritage education also fulfills its role of mediator.

Although the term “education” is always closely linked to the school context, the heritage education we are talking about is an education that goes beyond the walls of the school, understanding the educational space as the territory itself. What of all kinds does not escape the current dictates of formal education, unless we see what the Law of Guidelines and Bases, LDB – 9.394 / 96, which provides in its art. 1: “Education encompasses the formative processes that take place in family life, in human coexistence, in work, in teaching and research institutions, in social movements and civil society organizations and in cultural manifestations” (BRASIL, 1996).

At the same time, the processes by which cultural heritage is preserved and valued through education must adopt transversal, multi, poly, transdisciplinary principles, where one can not ignore the various symbolic and social interfaces. The Patrimonial Education that we want has to be seen as the medium and not as an end.

Given that many experiences have already been sacrificed at the stake of history, it is necessary to develop an educational process that respects these basic guidelines, that respects all the expression of this rich heritage of the Delta peoples. Thus, the BR Heritage Fair will also be a form of resistance and struggle.

These studies also propose to make feasible, instruments of analysis on important tools for the field of Museology, namely, “how to communicate” and “make known” to the public about the existence of strategy related to the protection, safeguard and promotion of the rich cultural heritage of the city of Parnaíba-PI, mid-northern region of Brazil.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

These brief reflections, still preliminary to a work in development, aim to bring to light the importance of regional (municipal) events that seek to perpetuate not only knowledge but the recognition of the individual as to its space, thus bringing the possibility of construction of belonging, and, consequently, the interest in creating actions linked to local development. In this way, using the BR Heritage Fair as an object of study, allows not only the reflection of this event, but also the opening of doors so that this event can be used as an example.

REFERENCES

BIONDO, Fernanda. The challenges of Education in the Field Cultural Heritage: Heritage Houses and Educational Action Networks. Professional Master in Preservation of Cultural Heritage. IPHAN. 2016.

BRANDÃO, Carlos Rodrigues (Org.). Participant research. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 2001.

BRAZIL. Constitution (1988). Constitution of the Federative Republic of Brazil. Brasília, DF: Federal Senate: Graphic Center, 1988.

FERNÁNDEZ, Luis Alonso. Introduction to the new museology. Editorial Alliance. Madrid, 1999.

FREIRE, Paulo, Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Rio de Janeiro: Peace and Earth. 1977.

GOMES, L. F. National cinema: paths traveled. São Paulo: Ed.USP, 2007.

IPHAN. Patrimonial Education: history, concepts and processes. Brasília: Institute of National Historical and Artistic Heritage, 2014., P. 19.

LDB – Laws of Guidelines and Bases. Law No. 9,394. 1996. Available at: <http://portal.mec.gov.br/seed/arquivos/pdf/tvescola/leis/lein 9394.pdf> Accessed June 2016

MAGALHÃES, Aloísio. Cultural goods: instruments for harmonious development. Brasília CNRC. s / d.

NASCIMENTO, Francisco de Assis Sousa; NASCIMENTO, Helder José Souza do. Municipal Plan of Culture of Parnaíba – 2015/2025. Municipal Superintendence of Culture / Management Secretariat. Parnaíba: Piauí. 2015.

GEO-ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT AND DIAGNOSIS PLAN AND ECONOMIC PARTNER OF THE PARNAÍBA DELTA APA. Ministry of the Environment – ICMBio, p.42.

PINHEIRO, Áurea da Paz; Page 6 Historical and Landscape Set of Parnaíba – Cadernos do Patrimônio Cultural do Piauí; v.2 – Teresina: Iphan Superintendence in Piauí, 2010.

VARINE, Huges de. The roots of the future: equity in the service of local development. Maria de Lourdes Pereira Horta. First Reprint – Porto Alegre. Medianiz, 2013.

VYGOTSKY, L. S. The Social Formation of the Mind. 6th Edition.- São Paulo: Martins Fontes, 1998.

[1] Paper presented for evaluation of the discipline Heritage, Society and Museum Education of the Graduate Program, Master in Arts, Heritage and Museology – UFPI, 2017.

[2] Master of the Postgraduate Program Master in Professional Arts, Heritage and Museology – UFPI.

[3] Master of the Postgraduate Program Master in Professional Arts, Heritage and Museology – UFPI.

[4] Tourist, PhD student in Geography, professor at the Federal University of Piaui.

[5] PhD in psychoanalysis from the International Seminary of Theology, Master of Science in Religion from the Mackenzie Prebiterian University.

[6] One can say of the idea of community participation in the definition and management of museological practices; of the adoption of Museology as a development factor and not only concerned with collections.

[7] Manoel Wenceslau Leite de Barros (Cuiabá, December 19, 1916 – Campo Grande, November 13, 2014) was a Brazilian poet of the twentieth century, belonging, chronologically to the Generation of 45, but formally to the Brazilian postmodernism. close to the European vanguards of the beginning of the century and the Pau-Brasil Poetry and the Anthropophagy of Oswald de Andrade. At the age of 13, he moved to Campo Grande (MS), where he lived for the rest of his life. He received several literary awards, including two Jabutis Awards and was a member of the Sul-Mato-Grossense de Letras Academy. He is the most acclaimed Brazilian contemporary poet in literary circles. While still writing, Carlos Drummond de Andrade rejected the epithet of Brazil’s greatest living poet in favor of Manoel de Barros. His best known work is the “Book about Nothing” of 1996.

[8] Available at <http://www.sigaa.ufpi.br/sigaa/public/programa/portal.jsf?lc=en&id=793>.

[9] Available for download at the official website of the Ministry of Environment ICMBio – APA Delta do Parnaíba – Management Plan: <http://www.icmbio.gov.br/portal/unidadesdeconservacao/biomas-brasileiros/marinho/unidades-de-conservacao -marinho / 2246-apa-delta-do-parnaiba>.

[10] The term ecomuseum is, in the specialized literature connected to Hugues de Varine and George Henri Rivière, in 1972 and 1980, respectively. In the Quebec Declaration in 1984, the principles of New Museology, which includes community museums, are laid; among them the ecomuseum, that must be constituted with the integration between patrimony, participative community, environment and territory. Considerations of museologist Áurea da Paz Pinheiro in the article COMMUNITY MUSEUMS, MUSEUMS SANS MURS: a participatory project to promote sustainability, citizenship and local knowledge.

[11] IPHAN. Patrimonial Education: history, concepts and processes. Brasília: Institute of National Historical and Artistic Heritage, 2014., P. 19.

[12] FREIRE, Paulo, Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Rio de Janeiro: Peace and Earth. 1977.