STATE OF ART

BARBOSA JUNIOR, Elenisio Rodrigues [1], CORREA, Thiago Pessanha [2]

BARBOSA JUNIOR, Elenisio Rodrigues. CORREA, Thiago Pessanha. Creation, Technology and Legislation: The Tripod of the Productive Chain of the Music Market Today. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 06, Ed. 06, Vol. 06, pp. 85-101. June 2021. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/art/productive-chain

ABSTRACT

This article is the result of a historical analysis of the advances of the music market to date and aims to be a contribution to generate reflections on the remuneration processes of authors, artists, interpreters, phonographic producers and other actors of the cultural scene. To this end, we have as a practical basis the three pillars of the phonographic industry: Music, Technology and Legislation, considering these three mechanisms as a reference for the consolidation of the cultural creative industry in Brazil. From a methodological point of view, we will describe six topics that will address: copyright, the transition of the music market, the impacts on production, the forms of remuneration, the dynamics of the music market, legislation and technological advances and music production on the Internet. Although recent transformations have a direct impact on the way of production and consumption of today’s society, the theme of this article is of great relevance and aims to elucidate the modus operandi of today’s cultural production chain.

Keywords: Music, Technology and Communication, Copyright, Production Chain, Artists’ Remuneration.

INTRODUCTION

Even in the 1970s, when Brazil was experiencing considerable advances in industry and sectors of the economy, the relationship between artists and publishers was amateurish. Therefore, at that time, the will of the publishers prevailed, establishing a disdainful relationship with the work of the artists. Martins Filho (1998, p.183), states that

Until then, a paternalistic relationship between editor and author prevailed. The one acting as a benefactor, and the one accepting the publication of his book as a favor, for he saw his writing as a mission, not a way of life. Talking about selling his book was almost heresy.

Thus, because they did not know their rights, the artists accepted that a third party — the publisher — would manage and publish their works, because they believed that what should be their work activity was a divine call and not a form of survival. In this logic, the work of editing and disseminating artistic works was seen as an act of kindness.

The rupture of this disinformation begins to happen when artists begin to realize that the market relationship that is established between their works and society is a matter of survival. Thus, a new stage begins, where artists/authors begin to position themselves as professionals and start demanding contracts that legitimize their rights and more effectively guarantee their work. This conflict was primarily due to the ignorance of existing laws by artists and because there is no legislation regulating and protecting intellectual works in Brazil.

If to date the copyright relating to the publication is almost totally unknown, what can we talk about other rights such as images, sounds, programs, hardware and software and the content made available on the Internet? To better understand this issue, this article aims to analyze, based on the timeline, the analog era of intellectual works until the current era, where digital information technologies and networks directly impact artistic production.

COPYRIGHT IN BRAZIL

Copyright was regulated in Brazil by Law 5,988 of December 14, 1973. This Law was subsequently repealed by Law 9,610 of February 19, 1998, which updated and consolidated copyright law, took other steps and began to take effect one hundred and twenty days after its publication.

In its Preliminary Provisions, the Law regulates the legal effects on legal business related to copyright, more specifically, those relating to authors, interpreters, phonographic producers, etc.

In article 5, it defines publication, transmission or dissemination, retransmission, distribution, communication to the public, reproduction, contrafation, work (co-authorship, anonymous, pseudonym, unpublished, posthumous, original, derivative, collective, audiovisual), phonogram, editor, producer, broadcaster, performers or performers and originating holder.

Article 6 stresses that “the works they simply subsidized shall not be in the domain of the Union, the States, the Federal District or the Municipalities”. In this sense, the State will not have the right to property over the works simply by subsidizing them. Thus, Article 6 definitely clarifies a problem that has generated much discussion. For a better understanding, the main aspects of the new copyright law will be defined briefly below.

Intellectual works protected the creations of the spirit, expressed by any means or fixed in any medium, tangible or intangible, known or invented in the future. Included here are texts of literary, artistic or scientific works; conferences, speeches, nods, etc.; dramatic and dramatic-musical works; choreographic works whose scenic execution is fixed in writing or otherwise; audiovisual works, sound or not, including cinematographic works; photographic works; drawing, painting, engraving, sculpture, lithography, kinetic art; illustrations and maps; projects, sketches and plastic works related to architecture, landscaping, scenography, etc.; adaptations, translations and other information of original works, presented as new intellectual creation; computer programs; collections, anthologies, encyclopedias, dictionaries, database, which, by their selection, organization or disposition of their content, constitute an intellectual creation. (MARTINS FILHO, 1998, p. 184).

Moreover, the author is the one who creates or gives rise to a literary, artistic or scientific work and can be known by the civil name, fictitious name or any that makes it recognized for its creation. In this logic, the copyright holder will also be the one who adapts, translates, organizes or orchestrates a work in the public domain and cannot owe another adaptation, orchestration or translation unless it is a copy of his authorship. Those who only helped the author in the production of the work are not considered co-author, since the co-authors are considered generators of the theme or literary-musical plot or who create the details used in the work.

“Copyright protection is independent of registration, but the author may record his work.” (MARTINS FILHO, 1998, p. 185). Thus, the authors can register their intellectual works in several institutions — The National Library, the School of Music and Belas-Artes of the University of Rio de Janeiro, among others — and legally validate their authorship.

The moral and economic rights of the intellectual work belong to the author, who will at any time claim the authorship of the creation when used by third parties. Thus, the author has the right to guarantee the integrity of his work and to owe any modification that may impair his honor as an author. In addition, you may also modify the work, remove it from circulation or suspend the use already authorized if the use implies an affront to your reputation.

THE TRANSITION OF THE MUSIC MARKET AND THE IMPACTS ON PRODUCTION

Do we remember the last time we stopped everything to listen to a record that was playing the device in our living room? Or do we identify more with the music-tapping scene and listening to our favorite music on our headphones as we move from place to place? The fact is that we change the habits of consumption of culture, be it music, books or movies. In this way, technology may have changed the forms of production, but the legislation has been adapted to guarantee the rights of workers in the cultural sector.

Digital technologies have transformed the habits of listening to music. Some time ago, carrying music with you required us a great deal of effort. It was necessary if you wanted to make an independent musical consumption of shows or musical performances – where you need co-presence – to have limited physical media; which made it arduous to exchange musical knowledge with other individuals or in other situations, as we see today. (SANTOS; MACEDO; BRAGA, 2016, p.1).

If today we listen to music on the internet, are the authors and artists who participated in the creative process of that work being paid for it? In view of this, Law 9.610 of February 19, 1998, applies to all digital platforms and also guarantees copyright in the era of the computer network.

It is known that society has undergone significant transformations in the way of consuming music. Our parents listened to songs on records and now we have everything in the palm of our hand and we can watch and listen to whatever we want. However, we have also had profound changes in the way of production in the digital age. Nakano (2010, p. 627) stresses that

Since the 1950s, the recording industry has undergone successive transformations, led by technological development. From a sector dominated by large verticalcompanies with a small diversity of products, it has become an industry in which small and medium-sized enterprises play an important role in prospecting trends and launching products. In it, manufacturing and distribution activities are carried out by specialized suppliers, and the market is shared between large and small and medium-sized enterprises. The Music Production Chain is currently going through a phase of uncertainties and uncertainties, due to the new possibilities created by the so-called “dematerialization of music”, that is, the distribution of music over the Internet or by mobile telephony.

It all assumes how production is made. In the past, we needed a large recording studio and the means of production were very expensive. However, what has been happening in recent years is that this access to technology has made forms of production very cheap.

Then, a few years ago, we saw a moment of production and the offer of content available today in the world increased tremendously, precisely because access that was once very prohibitive by cost has now become much more accessible for those who want to enter the music market.

FORMS OF REMUNERATION

As a lot begins to produce, other issues related to how to disseminate and distribute this content are now perseeded. And it is these changes that, along with the access facilities, have been causing the transformations in the music production chain that we see clearly happening, and in the midst of all this is the remuneration of the creators. According to Falcão; Soares Filho (2012, p. 54)

The author of the artistic work is entitled to receive monetary compensation for the use of his work by the user. This prerogative is housed in the Federal Constitution, which outlined the basic and indispensable guidelines for the protection of intellectual creations, ensuring, in article 5, items XXVII and XXVIII, letter “b”, which, as a rule, only the creator can set the price for the use of his work.

The big question in today’s music industry is: how are these authors and artists paid for their work? That will depend on how the music is used. There is still the traditional form of use – concerts, concerts and live performances. In this case, musicians are remunerated through the Central Copyright Collection Office (ECAD)[3], the show promoter pays a fee to ECAD and the office distributes it to all musicians.

Another way in which composers, artists and phonographic producers can be remunerated, is when they authorize the synchronization of this music in audiovisual works, that is, when a song enters a novel or a commercial film. Thus, the producer of the audiovisual work pays the right of synchronization to the authors and producers.

The internet is still the new frontier and there are new models of pay under test, and today, basically, we have a form of remuneration tied to the amount of views — streaming — and the number of accesses to music.

The word streaming is a stream derivation, which in English means stream. That’s why the term refers to a stream of data and various contents such as videos, music and games. It is very common on the internet to watch awards and games in live streaming, allowing the user to see what is being broadcast at that time. To work, streaming audio and video transfers your information through a data stream from a server. There is also a decoder that works as a type of web browser. The server, information flow, and decoder work together to make streaming happen. (SILVA JUNIOR, 2016, p.1).

So if today we subscribe to a music streaming platform and pay monthly for that subscription, we can listen to the songs we want. Therefore, these platforms make an internal calculation that, with each click, rights holders gain a certain percentage of the value from the users’ subscription. On the one hand, this abundance of content is very positive because it gives the user and the music lover almost infinite access to the wealth of music we have. However, the number of composers and authors who need to share relatively small resources greatly increases.

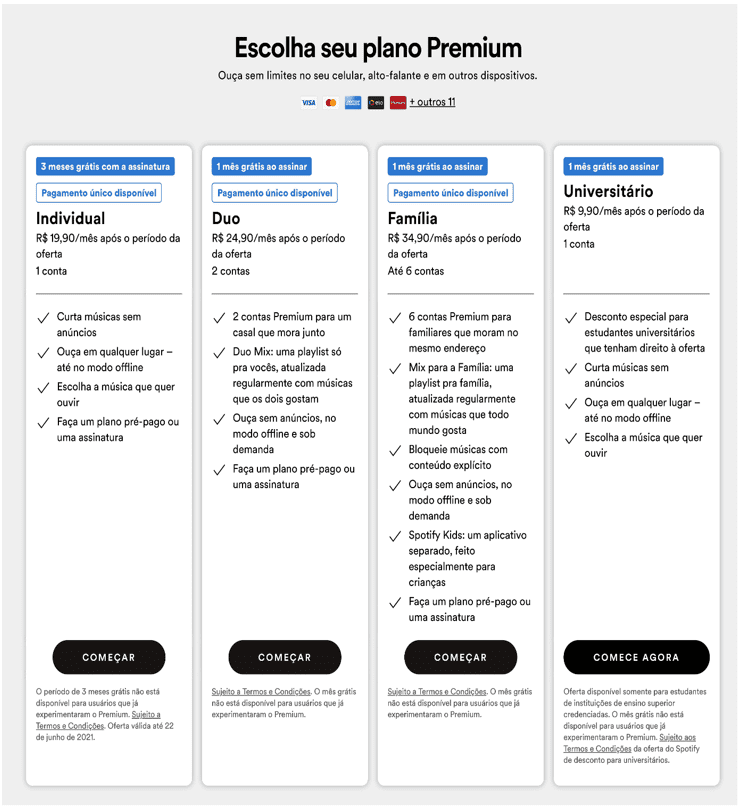

If we start from spotify’s most expensive subscription assumption —approximately 35 reais which is the family plan and entitle 6 people to listen to several songs per month—in the end, part of that 35 reais will be with the platform administrator and the other part will be distributed to the musicians, composers and record producers.

Figure 1 – Premium Plans

If we expand this issue, we will have the market for films and series that works exactly from the same compensation system. In this logic, the market seeks to adapt because the value cannot be so low as to make the remuneration of artists unfeasible or so high that it discourages the consumer from legal means. Therefore, the consumer discouraged to consume legally ends up opting for piracy, and this is the worst of all, because if you do not pay anyone, do not pay tax, which generates damage to the market.

THE DYNAMICS OF THE MUSIC MARKET

The dynamics of the market are interesting because by the time NAPSTER[4] appeared, it was as if the new world was opening new paths — all available at any time with the emergence of MP3 — that took the reins and the wall that surrounded the control of the major labels.

According to Martins Filho (1998, p. 187) “computer science is provoking the emergence of a new culture, with new concepts of commercialization”. In this sense, there was a total break of paradigms, where the entities that had greater control completely lost the management of those contents that placed on the market.

“New media technologies never cease to emerge at an increasingly intense pace until it becomes truly overwhelming from the advent of the digital universe.” (SANTAELLA, 2015, p. 46). From this angle, overnight, the market found itself in a situation where suddenly everyone could have access to everything they wanted, but had no control and no remuneration.

For a few years it seemed that the music market had collapsed and that model that perpetuated itself for many years was demolished. And really, in a way this phenomenon ended up bringing new paradigms to the music industry.

With the advance of technology, at that time the legislation could not keep up with technological development, because it could not pay and neither had a designed business model. Pereira (2011, p. 119) states that “popular music itself was a phenomenon on a global scale, involving increasingly dynamic and complex processes of production, distribution, circulation and consumption”. Over the years, consumption and behavior habits have changed and technology has become based on how people consume and deal with it.

Inevitably, even before having this logic of the current music market, technology companies implement a new reasoning. Apple itself launched a hardware product in 2001 — iPod — and decided there should be a way for people to legally consume music. At that time, the iTunes store was launched. It was at this point that the format in which the music industry had worked all its life was completely broken — format in physical support.

The music industry has lived on a long time of hits and to this day works, but the hit was based on an entire album. The entire disk was purchased due to the acquisition of only one phonogram.

From the moment iTunes released that new model, it established two totally innovative paradigms —track sales and the single price—because the industry has always relied on more expensive release discs and older-priced catalog discs.

At that time, there was a leveling of all the albums, from the new release of Metallica to that old album jorge ben, all with the same price. Therefore, it was a complete paradigm break and a new business and compensation model was established. Thus, we can say that music is one of the main responsible for the monetization of content available on the Internet.

LEGISLATION AND TECHNOLOGICAL ADVANCES

The Brazilian copyright law — Law 9,610 of February 19, 1998 — pre-emptoses the Internet and has not been able to closely monitor these significant changes. Consequently, it has undergone some adjustments over this time, mainly in the area of collective music management. However, we cannot say that it has been fully adapted to the world of the internet,which does not mean that it does not apply to the network.

The basic concepts of copyright remain applicable to the Internet and no one can use the work of a composer without his or her permission or the holder, it was so before the internet and continues to be.

Such authorisation may be free of charge or paid and from there all cultural workers are paid. This includes the composer, the music producer, the arranger and everyone who worked artistically in the design of that work and the completion of that product. From this point of view, the Creative Commons license appears. Araya; Vidotti (2010, p. 97) point out that,

Creative Commons is a non-profit voluntary membership project based at Stanford University in the United States. He is responsible for a new form of copyright, as it provides a set of licenses for audio, image, video, text and education that allows authors and creators of intellectual content, such as musicians, filmmakers, writers, photographers, bloggers, journalists, scientists, educators and others, to indicate to society, in an easy, standardized way, with clear texts based on current legislation , under what conditions your works may be used, reused, remixed or legally shared.

Thus, there are a number of contracts in production in which artists give up or license these rights for certain remunerations. In the end, the figure of the holder who is the owner of the property rights on that song. In addition, it is still necessary the permission of the owner to use the work on the internet. From this perspective, it is not because the content is found on the internet that it is free of copyright. The correct thing is, if you found content on the Internet, this site probably negotiated that content with the owner. Therefore, the legislation continues to protect the author, with only a few changes.

There is no way for legislation to evolve at the same speed as technology, since technology is evolving very fast and the change in legislation is bureaucratic, as it requires discussion with society and approval of the National Congress. Therefore, the judiciary often plays this role, and through judgments in its day-to-day lives, jurisprudence — the understanding and decisions reiterated by the judiciary — often comes faster than the legislation itself. When interpreting the law, the judiciary has taken care of the application on the Internet.

So we can say that today to talk about copyright on the internet, it is not enough to look at legislation, we need to look at legislation and jurisprudence because the change of the law is very slow and technology is very fast.

MUSIC PRODUCTION ON THE INTERNET

There is an issue that is important when we talk about music production, record companies have been adapting to this new format of the industry, but we have autonomous artists who also have the facility to produce home content and have a Channel on YouTube.

YouTube is the main musical destination on the planet, because as the content there is on demand, the user can see what they want and anytime they want. At the time this technology was invented, YouTube was asked by the record companies themselves that people used to use third-party content that belonged to these companies. As a result, with the passage of time, Content ID appears. For YouTube (2018a)

Content ID is a tool used to easily […] identify and manage content on YouTube. Contend ID is an algorithm that searches for and identifies matches in videos that are uploaded to YouTube and copyrighted materials. In practice, it checks every video that is uploaded, comparing it with “database”, or “references”, which is formed by files sent by the content owners themselves. When a match is found the video receives a Content ID claim (apud AMARAL; BOFF, 2018, p. 50).

Thus, YouTube has created a business model that is fundamental in the industry, which today creates a system that basically allows the phonogram to be detected by the system every time the record label owns the content inserts it into the platform system.

This system creates a layer stating which company that song belongs to. Thus, in relation to other legal entities or individuals who use third-party music, the system on YouTube detects and remunerats in order to create a business model that is now sustainable and many companies and many artists do not just live on music, but also live from creating their own channels.

This works both for artists who have created their own channel using it as a dissemination and propagation tool, as well as for songs that are used on personal channels in sports videos, birthday parties, etc. Any music used on the YouTube system allows the content owner to be paid, which therefore created a new business model that didn’t exist until recently.

In relation to all these issues, Brazil, being large, is considered one of the three largest countries of social engagement on YouTube and is among the ten largest monetization countries in the world. This brings, on the part of content providers, greater attention when it comes to seeing the content they know how to generate audience. So today the competition saw that people want to have the end user’s attention at home. In this way, a new profession emerges — YouTuber — that has spawned the celebrities that everyone knows from an audience that was born at home, and so did the artists.

A hallmark of this audiovisual content producer on YouTube, YouTuber, is the ability to produce content with reduced teams and the relationship it manages with the consumer audience. Unlike the previous relationship of traditional media such as film and television, there is no support from large companies for building a celebrity. The current scenario presents a content producer who must build his reach and his ability to “influence” from the relationship he develops with other producers, with brands and with the public. (LEITE, 2019, p. 44).

Many artists we know today were driven by major labels because, in the past, it was very expensive to promote and develop their career. An example of this is Justin Bieber, who like many other artists emerged from the audience he created himself.

There are radios that today take covers that play on YouTube and put in their playlists. Thus, many songs that have emerged spontaneously and often do not even reach the traditional environment — radio and television — have gone viral from the social network, and most importantly, they are being monetized and remunerating the content owner.

Our legislation is failing to monitor, promote or pursue these changes. Therefore, these advances and all this new form of remuneration, prohibition or use of online content,in fact, are isolated movements of updating.

An example of this is that the Ministry of Culture launched a Instrução Normativa[5] on collective copyright management in the digital environment, which deals with how artists, authors and rights holders can join collective management associations to monetize, receive and distribute the resources coming from the internet.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

In practice, this world is so new, it has changed so fast, that an institutional and legislative rearrangement and a renegotiation between the different market players is really necessary for everyone to understand that, in reality, there is no old and new media, the media are always the same and today everyone is in the digital world.

What exists are creators, producers and distributors of content. Therefore, if the creator and producer are not paid, no third party needs to distribute. Everyone is aware of this, including the actors in this story who are reluctant to pay copyright and who for a while thought it was not necessary because this model was dead. But even these actors have already realized that without content that makes sense, the most modern iPad, iPod or any other technology are just trinkets. From this angle, people listen to music and watch movies, and at the end of the day, the important thing is the content.

In fact, the music never had so much weight, because at the end of the Olympic ceremony, we saw that the music walked the event in its entirety, strolling through all Brazilian cultures.

The fact is that these main sources of revenue of the artist and the author – public execution, synchronization and right of reproduction – what has changed is that for some time there was no streaming, because broadband was not yet enough and the business model was not approved.

The download model was similar to the disc —downloaded, sold for one, and paid x. When the streaming model comes up, there are questions about which right you actually have to pay.

As certain content is transmitted, some strands believe that this right is part of the public execution model and others think not, because it is a private right because I am paying and choosing. The discussion that is on the agenda in Brazil is precisely how much of this remuneration should or should not be put into public execution.

This is a discussion that has not come to a very quick conclusion, but Brazil will probably lead this process globally, because we are a highly significant country in terms of volume.

The companies that operate today in the digital market are somewhat enthusiastic about Brazil, because we have a population where much is produced and much is consumed. Consequently, we have a layer of cell phones and subscribers much larger than that of inhabitants.

This brings incredible relevance to the market. Therefore, we have to streamline the modes of operation for the production chain to be officially established.

REFERENCIAS

AMARAL, Jordana Siteneski do; BOFF, Salete Oro. A Falibilidade do Algoritmo Content ID na identificação de violações de Direito Autoral nos Vlogs do YouTube: Embates sobre Liberdade de expressão na Cultura Participativa. Revista de Direito, Inovação, Propriedade Intelectual e Concorrência, Porto Alegre, v. 4, p. 43-62, Jul/Dez. 2018. Disponível em: https://bit.ly/3fofLyz. Acesso em:27 mai. 2021.

ARAYA, Elizabeth Roxana Mass; VIDOTTI, Silvana Aparecida Bursetti Gregório. Criação, proteção e uso legal de informação em ambientes da World Wide Web. São Paulo: Editora UNESP, 2010. Disponível em: https://bit.ly/3wDWyz0. Acesso em: 27 mai. 2021.

BRASIL. Instrução Normativa n°2, de 4 de maio de 2016. Estabelece procedimentos complementares para a habilitação para a atividade de cobrança, por associações de gestão coletiva de direitos de autor e direitos conexos, na internet, conforme definida no inciso I do caput do art. 5° da Lei n° 12.965, de 23 de abril de 2014. Disponível em: https://bit.ly/3wvs02a. Acesso em: 24 mai. 2021.

——————. Lei 5.988, de 14 de dezembro de 1973. Regula os direitos autorais e dá outras providências. Brasília: Casa Civil, [1973]. Disponível em: https://bit.ly/33SbLzU. Acesso em: 16 abr. 2021.

——————. Lei n° 9.610, de 19 de fevereiro de 1998. Altera, atualiza e consolida a legislação sobre direitos autorais e dá outras providências. Brasília: Casa Civil, [1998]. Disponível em: https://bit.ly/3yh5YSF. Acesso em: 16 abr. 2021.

FALCÃO, Caio Valério Gondim Reginaldo; SOARES FILHO, Sidney. Direito autoral e ecad: análise jurisprudencial do papel do escritório central de arrecadação e distribuição na cobrança judicial pela execução pública de obras musicais e congenêres. Revista Jurídica da FA7, Fortaleza, v. 9, p. 53-64, 30 abr. 2012. Disponível em: https://bit.ly/3whHd72. Acesso em: 24 abr. 2021.

LEITE, Rafaela Bernardazzi Torrens. Youtuber: o produtor de conteúdo do Youtube e suas práticas de produção audiovisual. 2019. Tese (Doutorado em Estudos da Mídia e Práticas Sociais) — Centro de Ciências Humanas, Letras e Artes, Universidade Federal do Ro Grande do Norte, Natal, 2019. Disponível em: https://bit.ly/3wsg5SA. Acesso em: 24 mai. 2021.

LIMA, Mauricio Marley Saraiva. A evolução do mercado musical: da” pirataria” às novas mídias digitais. 2013. Monografia (Graduação em Ciências Econômicas) — Faculdade de Economia, Administração, Atuária, Contabilidade e Secretariado, Universidade Federal do Ceará, Fortaleza, 2013. Disponível em: https://bit.ly/3tXxctZ. Acesso em: 03 mai. 2021.

MARTINS FILHO, Plínio. Direitos autorais na Internet. Ciência da Informação, v. 27, n. 2, p. nd-nd, 1998. Disponível em: https://bit.ly/3whEeeA. Acesso em: 28 abr. 2021.

NAKANO, Davi. A produção independente e a desverticalização da cadeia produtiva da música. Gestão & Produção, v. 17, n. 3, p. 627-638, 25 out. 2010. Disponível em: https://bit.ly/3bB2TD7. Acesso em: 09 mai. 2021.

PEREIRA, Sónia. Estudos culturais de música popular: uma breve genealogia. Exedra, Coimbra, v. 5, p. 117-133, 2011. Disponível em: https://bit.ly/3umeOv9. Acesso em: 25 mai. 2021.

SANTAELLA, Lucia. A grande aceleração & o campo comunicacional. Intertexto, Porto Alegre, n. 34, p. 46-59, set./dez. 2015. Disponível em: https://bit.ly/3fNN3pS. Acesso em: 25 mai. 2021.

SANTOS, Bluesvi; MACEDO, Wendell; BRAGA, Vitor. O streaming de música como um estímulo para a ampliação do consumo musical: um estudo do Spotify. In: CONGRESSO BRASILEIRO DE CIÊNCIAS DA COMUNICAÇÃO, 29., 2016, São Paulo. Anais […]. São Paulo: Intercom – Sociedade Brasileira de Estudos Interdisciplinares da Comunicação, 2016. Disponível em: https://bit.ly/341MFhX. Acesso em: 20 abr. 2021.

SILVA JÚNIOR, Flávio Marcílio Maia e. Na Onda do Streaming: Plataformas Digitais Sonoras no Mercado Musical Brasileiro. In: CONGRESSO DE CIÊNCIAS DA COMUNICAÇÃO NA REGIÃO NORDESTE, 18., 2016, Caruaru. Anais […]. Caruaru: Intercom – Sociedade Brasileira de Estudos Interdisciplinares da Comunicação, 2016. Disponível em: https://bit.ly/3bYIdVT. Acesso em: 26 mai. 2021.

SPOTIFY Premium. Spotify (BR), Premium, 27 mai. 2021. Disponível em: https://spoti.fi/2QYkPk1. Acesso em: 26 mai. 2021.

APPENDIX – FOOTNOTE REFERENCE

3. Currently, The ECAD is administered by ten music associations, based in the city of Rio de Janeiro, with 25 collection units, 700 employees, 60 lawyers providing services and 131 autonomous agencies installed in all states of the Federation. (FALCON; SOARES FILHO, 2012, p. 56).

4. NAPSTER was a program developed with the intention of sharing files in a “peer-to-peer” (P2P) network where the user could download music, videos, programs, games for free. (LIMA, 2013, p. 16).

5. NORMATIVE INSTRUCTION MINC No. 2, OF MAY 4, 2016: Establishes complementary procedures for the qualification for the collection activity, by associations of collective management of copyright and related rights, on the Internet, as defined in item I of the caput of art. 5 of Law No. 12,965, of April 23, 2014. (BRASIL, 2016).

[1] Specialization in Arts and Education from College Luso Capixaba and bachelor’s degree in Music with A Degree in Piano from the College of Music of Espírito Santo “Maurício de Oliveira”.

[2] Specialization in Arts and Education by the Higher Institute of Education of Afonso Cláudio and graduation in Music and Technical in Popular Music / Piano from the College of Music of Espírito Santo “Maurício de Oliveira”.

Submitted: May, 2021.

Approved: June, 2021.