ORIGINAL ARTICLE

PANTOJA, Josicleia da Silva [1], MARTINS, Maria das Graças Teles [2]

PANTOJA, Josicleia da Silva. MARTINS, Maria das Graças Teles. Interpersonal communication skills between couples: Contributions of cognitive behavioral therapy. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 05, Ed. 10, Vol. 15, pp. 138-164. October 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/psychology/interpersonal-communication

SUMMARY

Couples, time and time again, live everyday marital conflicts, but the big question is how these conflicts are resolved by them. It is understood that skilled communication between couples can provide marital satisfaction and better resolution in the problems that arise. The aim of this study was to investigate the social communication skills in the marital relationship and the contributions of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy – CBT. We also sought to identify the positive and deficient forms of communication in the marital relationship. The methodology used was the field research of quantitative-qualitative and exploratory character. The instruments applied were the Inventory of Marital Social Skills – IHSC, in 20 (twenty) people formally married or not, members of a religious institution in the city of Macapá-AP. The results indicate that women have a greater deficit in proactive self-control and men have greater difficulty in assertive conversation. The final considerations reflect that: Social skills, communication training, assertiveness and problem solving are technical components used by CBT that can help in the form of communication of couples, so that they can acquire strategies that alleize their conflicts. The cognitive behavioral therapist will seek to favor the couple, through cognitive-behavioral techniques and strategies, the skills necessary for positive communication. It may provide agreements between peers for cognitive, affective and behavioral change, because the intervention in CBT aims at establishing balance in the relationship, reducing conflicts and cognitive distortions that permeate the couple’s relationships.

Keywords: Communication skills, marital relationship, cognitive behavioral therapy.

1. INTRODUCTION

This study presents the results of a field research, of quantitative-qualitative and exploratory character, in which we sought to investigate the social communication skills in the marital relationship and the contributions of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy – CBT. We also sought to identify the positive and deficient forms of communication in the marital relationship and the development of assertive and positive communication.

It is not new that couples, time and time again, live everyday marital conflicts, however, the big question is how they solve these conflicts and how difficult it is to solve relationship problems affects the marital relationship. Many of these conflicts occur due to the difficulty of communication between peers, of expressing their feelings, of judgment, of the lack of understanding of the other and, sometimes, even for fear of exposing themselves within the relationship.

According to Mundim (2010), currently couples go through many challenges, such as stress, unemployment, physical and emotional diseases, children, precarious transportation, lack of time. Couples who have difficulties in dealing assertively with daily difficulties and specific situations may have some inappropriate behaviors that lead to physical and mental exhaustion, that is, that interfere with affection, feelings and emotions.

For Silva and Vandenberghe (2008), communication involves the process where one speaks and the other hears, which despite being a fact that occurs daily in people’s lives, when it comes to couples, acquires particular elements. These same authors note that the inability of positive communication can generate, potentiate or even maintain marital conflicts.

The motivations for the choice of this theme occurred during internships performed within the academy, where it was possible to experience some activities such as; psychological listening, wheel of conversations in school institutions with adolescents who reported family conflicts with parents’ disagreements and lack of communication in the home. A significant number of children and adolescents who suffer from family conflicts, with the difficulty of intrafamily communication, with the absence of communication between parents can be observed, directly affecting the entire family context. Based on these observations, it was thought to collect data, through field research, on how couples have communicated, to confirm or not whether there is a deficiency in this communication process.

This study is justified by the relevance of the theme in several areas of knowledge such as psychology, education, social, mental health, among others. It is relevant for the psychology professional, since opportunities are offered so that interventions can be developed in the clinic and community. It is noticed that there are several studies related to interventions with couples, however, there is little research in the field of psychology carried out in the city of Macapá because it is still sensitive, requiring expansion of investigations and scientific production aimed at this public.

It is understood that in order to work with couples, with or without children, it is necessary to have the presence of psychology, and that, in their work, try to look at the way in which these families have solved their issues and, when they cannot, verify which positive strategies for assertive, empathic, affectionate, comprehensive communication can be used to solve their problems. The authors Bertoni and Bodenmann (2010, apud COSTA; CENCI And MOSMANN, 2016) clarify that situations of conflicts in conjugality occur due to the process of adaptation, synchrony and maturation of the relationship over time. They explain that marital conflicts occur naturally and are the interactional fruits of people who wish to build life projects together. To do so, they need to discuss, negotiate and reach agreements. Communication becomes a point of attention in this relationship because assertive communication becomes more efficient in the relationship of couples.

Therefore, CBT has excellent and diversified strategies of therapeutic interventions for various disorders and presents itself as a form of therapy that effectively contributes to couples therapy. Beck (1995) pointed out that many problems experienced within marriage could be related to the dysfunctional cognitions of both partners. In his studies, he ratified the negative role of thoughts, beliefs, expectations, attributions, among others that may be inserted in the quality of conjugal relationships.

The modality of Beckiana cognitive behavioral therapy consists in the analysis and modification of dysfunctional thoughts that are determinant in the mood state, affect and behaviors of the couple. Peçanha and Rangé (2008) assert that CBT has been used in various problems with interventions, including issues of couples in dismay.

Thus, we sought to question: How does cognitive behavioral therapy contribute to the development of social skills of assertive and positive communication in the couple’s relationship? It is understood that marital conflicts permeate the marital relationship in all its facets. There are many problems that can lead the couple to negative or ineffective communication, with conflicts and discussions, among which are specific difficulties, such as dissatisfaction in the sexual area, small children, adolescents, among others that cause a lot of stress and anxiety.

Therefore, The Couple’s Therapy is effective, as Dattilio (2011) explains when it states that within the treatment with the cognitive behavioral approach, it is important for the therapist to educate couples and families about the treatment model. It states that, within the structure and collaborative principles of the approach, it is necessary that the family and its members understand the principles and methods involved in this process. Cognitive-behavioral interventions can be performed individually, in groups, with a couple and with children.

The main objectives of CBT in the treatment of couples in conflict are the restructuring of inadequate cognitions and the modification of dysfunctional communication patterns, in addition to the development of strategies to solve daily problems. Thus, the CBT approach contributes to family well-being, improving the communication of its members, starting with those responsible for the family, which is sometimes the couple.

2. METHODOLOGICAL PROCEDURES

For the development of this study, the methodology used was quantitative-qualitative and exploratory field research. In order to investigate the social communication skills in the marital relationship and the contributions of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. We also sought to identify the positive and deficient forms of communication in the marital relationship, and the development of assertive and positive communication. Gil (2017) explains that the field study seeks to deepen a specific reality. The exploratory research aims to “provide greater familiarity with the problem, with a view to making it explicit, building hypotheses and improving ideas”, involving bibliographic survey, interviews with people experienced in the problem researched (GIL, 2017, p. 41). Field research implies the use of previously established measures, the results of which are quantifiable, ensuring the establishment of safe and reliable conclusions (GIL, 2017; CERVO; BERVIAN E SILVA, 2013).

Richardson (1999, p. 70) states that “The quantitative method, as its name implies, is characterized by the use of quantification, both in the modalities of information collection and in the treatment of information through statistical techniques”. In the quanti-quali or quali-quanti research, two stages of research are developed: in the first, the qualitative phase is conducted to know the phenomenon studied, later in possession of the information, it is left to build a closed questionnaire and applies in the field appointed for research. The following are the tabulation steps, performing data analysis with the aid of statistical instruments. (RICHARDSON, 1999; GIL, 2017; CERVO; BERVIAN E SILVA, 2013). This style of research involves the interest of the researcher, interest to the research problem that often depends on multiple approach to investigation.

2.1 SAMPLE

The research sample consisted of 20 (twenty) married people, formally or not, heterosexual, aged between 22 and 60 years, who had a marital relationship for more than 2 (two) years, having attended at least high school, belonging to a religious institution located in the city of Macapá-AP.

2.2 DATA COLLECTION PROCEDURES

For data collection, the Inventory of Conjugal Social Skills – IHSC by Villa and Del Prette (2012) was used as a research instrument, initially composed of information referring to sociodemographic data, in order to identify and describe the participating subjects. Subsequently, the instrument, which contains 32 (thirty-two) items, will assess the frequency with which behaviors or feelings of social skills are emitted within the marital context, where each item will describe a specific situation that occurs within the marital context, and a feeling or behavior towards this situation. The participant will choose to mark the frequency that emits such behaviors or feelings, being from 0 to 2 (zero to two) where for every 10 situations I react this way at most 2 times; 3 to 4 (three to four) for every 10 situations I react this way a maximum of 4 times; 5 to 6 for every 10 situations I react this way a maximum of 6 times; 7 to 8 (seven to eight) for every 10 situations I react this way a maximum of 8 times and / or 8 to 10 (eight to ten) for every 10 situations I react this way a maximum of 10 times. The participant could not leave any inventory item blank. It was explained to the respondent that, if the situation described in the item had never occurred, he should imagine that, if it happened, how he believes he would react.

The research followed the following steps: Definition of the theme by the researcher; Bibliographic survey to organize the theoretical framework; Reading of the material; Preparation of the Project; Delivery and defense of the Project; Project Review; Literature review; Contact with the research participants for the explanation and signing of the Free and Informed Consent Form (TCLE); Application of the Instrument; Preparation of the scientific article and defense of the scientific article.

2.3 DATA ANALYSIS

The analysis of sociodemographic data was performed through the Excel 2016 program, in which groups were performed according to similarity and calculations of means and frequencies were performed. The results of the application of the instrument used for the research were calculated in two ways, the first in a computerized way for 5 (five) participants, where the respondent’s data were transported to the online form available where the percentiles were obtained, as well as the interpretation of the results. The second form was for 15 (fifteen) participants and the calculation was manual, carefully and judiciously following the instrument manual.

This study was analyzed and approved by Plataforma Brasil, which is responsible for the official research launch system for analysis and monitoring of the CEP/CONEP system, according to opinion no. 16296319.3.0000.5021. Therefore, the Informed Consent Form (TCLE) was used to manifest their consent to participate in the research, according to resolution 466/12 of the National Health Council (CNS).

3. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

3.1 SOCIAL COMMUNICATION SKILLS IN MARITAL RELATIONSHIP

Communication is present in everything that the human being, since birth, goes throughout life, being fundamental for the maintenance of the social relations of individuals. In the first contact relationships, one can perceive how communication develops and gaining different meanings, where the baby begins to learn to communicate with the other in a unique and particular way. Crying sometimes gains different meanings, from hunger to pain, in which, for each pain, a different cry.

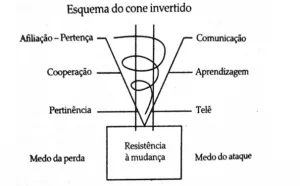

Within this process of becoming social, each interpersonal relationship will reflect an essential part of human experience, and for the maintenance of relationships, it will depend largely on the development of social skills (HS). Thus, interpersonal relationships are an integral part of human nature and permeate all life, being present directly or indirectly in the various stages of our development (PORTELLA, 2011).

In general, in order for good communication to be obtained within interpersonal relationships and that there is also synchronism in this communication process, it is inferable that it is necessary to have socially skilled individuals. Caballo (2010) points out that being socially skilled is having a set of behaviors that are issued in an interpersonal context, which express feelings, attitudes, desires, opinions or rights of this individual, appropriately to the situation, likewise respecting this behavior in the other, besides that these skilled subjects, usually solve the immediate problems of the situation, minimizing the likelihood of future problems. Thus, in order to maintain the most intimate relationships, verbal communication is an instrument of paramount importance (FIGUEIREDO, 2005).

In agreement, nonverbal communication is part of daily life and has no idea of its occurrence, and not even as it happens, because it is natural for individuals (SILVA et al., 2000), elucidating these forms of communication to a couple’s relationship, according to Rosset (2016), speaking what it needs and, if necessary, speaking and feeling that it has been understood, is the soul of the conjugal relationship.

In a conversation, it is necessary to have this discontinuous feedback, however, frequent, to know which answer, even so that it can suit those who are listening. For those who speak, it is essential to know if it is being understood, whether the listening person is agreeing or not, or even if it is being pleasant or not (CABALLO, 2010).

Portella (2011) presents empathic ability as the third social ability of communication, and according to Rogers and Rosenberg (1977 apud PORTELLA, 2011), the empathy that is in you penetrates the perceptual world of the other, and in doing so, feels at ease within it. Almeida (2013) says that empathy is paramount in relationships as well as in communication. For Chapman (2013), encouraging the spouse requires a certain empathy, a look at the world from the perspective of the spouse, first discovering what is important to his partner, so if he is able to encourage him. Empathy is explicitly and significantly related to all points of marital satisfaction (SARDINHA; FALCONE; FERREIRA, 2009).

For Dattílio (2011), when the couple and family members are provided with the practice of the three types of reactions, the non-assertive, assertive and aggressive, of each other, it can be useful to help them understand that the benefits of having assertive behaviors can make the relationship healthier.

Thus, one of the ways to enrich the marital relationship is to improve communication, so that the couple builds an effective and healthy relationship. Dealing with everyday problems is not always so simple or easy. Thus, seeking to acquire skills of dealing with conflicting and normative situations of any marital relationship should be part of the objectives of every couple. In view of this, the couple achieves more appropriate ways of making important decisions for the relationship, in various areas of married life, as well as finances, the relationship with the children, about the care of the house and even about the future of the relationship.

3.2 FORMS OF POSITIVE AND DEFICIENT COMMUNICATION IN MARITAL RELATIONSHIPS

Social and communication skills between couples are an important factor for marital relationships. Positive communication generates well-being in the relationship, on the other hand, negative or fragile communication influences the dynamics of the couple and generates conflicts and insatisfações. Deficient communication is a problem commonly encountered in couples who, in an attempt to resolve their conflicts, end up further aggravating the situation, or trigger a new problem. Thus, the lack of communication skills becomes particularly destructive, and can generate, potentiate or maintain marital problems (SILVA E VANDENBERGHE, 2008).

Couples who, when trying to solve their problems, end up using ineffective communication, end up further aggravating the conflicting situation or may even motivate other problematic situations (SILVA E VANDENBERGHE, 2008).

For Hanns (2013), destructive communication in general does not favor marital life, even depending on the culture, season and habits of the family, and even if they are part of the couple’s daily life. According to Chapman (2013), the way in which one speaks is extremely important, the author brings the importance of when for some reason the partner communicates with aggressive words, in this moment of anger, it is necessary to choose to remain kind, so it will no longer react aggressively to use soft words.

In this scenario of negative communication, there are many factors that can influence the inability to pass or receive an effective message within this relationship, among them the difficulty in clarifying an emitted message, which may be related to various reasons of the individual and also of his partner, because communication is a two-way street, as information is issued , the objective is sought to be understood, and when the other party does not give this support, there may be failure in this communicative process.

There are many implications for effective communication, among other things, the very environment where the couple’s conversation takes place. It is necessary to have an appropriate place, it is essential to look at the tone of voice, as well as the attitude of those who listen. It is necessary to be attentive and receptive to this communication, because when there is no such flexibility and empathy in listening, considering what the other has to say, a certain blockage can be established in this process and, consequently, marital conflicts emerge vehemently.

In the relationship of a couple, communication is incessant and intense, so it is necessary that the couple learn to talk about their way of communication, because otherwise, feelings are being kept and becoming increasingly embedded and that when not expressed, generate nonverbal communications. In this context, everything starts to be communicated in a non-verbalized way, and consequently the distancing of the couple happens, having difficulty to make clear what they feel, want or think (ROSSET, 2014).

This author presents the existence of some communicational compulsions that happen to most couples, and that require some attention, among them, the habit of trying to reassure or give advice when the partner just wants to speak what he/she is feeling, what he/she is going through or living in a certain situation. The author refers to the exercise of listening, in a search to try to understand what others are talking about, seek to see the situation from the point of view of the other, where it becomes more useful than wanting to give solutions or criticism.

Therefore, empathic listening can be a good exercise for such a situation, and the partner really wants only someone who understands him without judgment, who allows him to speak freely, of his pains, afflictions or even of a bad or non-productive day of work. Godinho (2015, p. 16) describes that:

Empathy can also be achieved through careful listening about what the other person says, often a very broad understanding of the perspective of the other is only to listen to what he has to say, without necessarily having to put himself in his place.

Therefore, if the person (in this context, the partner) is heard openly and attentively, there is the possibility of knowing the experiences of this individual, being able to contact more quickly with his internal world. To do so, it is willing to learn to see the conflicting situation of the other, from what is relevant to that person, is to know how to actively listen within the conjugal relationship, it is in one way or another to give momentarily their personal issues, in order to help the other, to give the other what they would also like to receive.

At first, talking about the other, instead of talking about oney, may be configured in another compulsion. Many couples, when they have difficulty in this communication process, end up opting for a more accusatory speech, even if unconscious, make use of pointing at the other or exposing the behavior that in their view is negative, in order to justify their frustrations, annoyies or negative feelings.

Destarte; Otero and Guerrelhas (2003) are unanimous in explaining that communication involves one speaking and the other listening, and vice versa. However, when it comes to couples, this situation is common place in people’s lives, presents itself with peculiar elements. The communication between couple has different characteristics and components. In addition, in the interaction of the couple there are some conflict-triggering behaviors that Chistensen and Jacobson (2000); Silva and Vandenberghe (2008) call triggers. They are the criticism, the demand, the accumulation of annoyances, sorrows and rejection that somehow trigger disagreements that, in turn, are interpreted and absorbed with suffering and wear.

The placements about what the person feels or thinks are more feasible and convey the reality of their feelings. In this way, the partner will know what his behavior triggers in the other, exemplifying to refer to the phrase: I was hurt because you did not arrive at the agreed time to go to the supermarket, becomes more useful than saying: You are completely irresponsible, only think and yourself and never arrive on time, so talk about yourself and how you feel about such attitude of the companion is a more effective communication than accusations , because when one arrives with such procedures of blaming the other, the partner will soon act defensively, and with this both will have difficulty understanding each other, as Rosset (2014).

Thus, the interruption during the other’s speech is another habit detrimental to the couple’s communication, in which the training of stopping the impulse to interrupt the partner’s speech can lead the person to discover even more of that person with whom he relates. To try to deal with anxiety to talk is to have self-control in a conversation, is to appropriate sensitivity with the other and to allow the person to express himself in the moment of it.

3.3 CONTRIBUTIONS OF COGNITIVE BEHAVIORAL THERAPY TO SPOUSAL POSITIVE COMMUNICATION SKILLS

CBT was developed in the early 1960s as a brief therapy focused on the present and depression, aimed at resolving current conflicts and modifying cognitions and dysfunctional behaviors (BECK, 1964 apud BECK et al., 1997). Its forerunner, Aaron Beck, developed theories and methods for cognitive and behavioral interventions in people with mental disorders (WRIGHT; BASCO AND THASE, 2008). Beck, in dedicating himself to a series of experiments, eventually obtained results that led him to new explanations for depression, identified negative cognitions, especially thoughts and beliefs that were the primary characteristics of depression. Beck also developed a brief treatment that had as one of the objectives to test the evidence of the thoughts of depressive patients (BECK, 2014).

Different authors explain that CBT presents itself as the second wave of therapies aimed at working with couples. It was preceded by behavioral therapy that had its emergence in countries that experienced a significant discrepancy in gender and rigid roles regarding the roles of men and women within the family. After the end of world war II, as a result, many men were removed from the labour market, thus making room for women. This new social configuration certainly led to a change in marital structure, so the partners, to live as a couple, more than before, would now need communication skills and problem solving in the marital relationship (VANDENBERGHE, 2006).

Accordingly, Peçanha and Rangé (2008) report that behavioral therapies had important influences when developing techniques for the treatment of couples. According to Beck (1995), among the pioneers in the work of solving marital problems are Dr. Janis Abrahms, David Burns, Frank Dattilio, Stower Hausner, Susan Joseph, Chris Padesky and Craig Wiese, all of which worked with cognitive focus.

The specialized literature describes that Cognitive Behavioral Therapy applied to couples, was introduced almost 50 years ago with Albert Ellis, who brought the importance that cognitions play in marital conflicts, and that dysfunctions in the couple’s relationship happen when they begin to hold irrational beliefs and without evidence about their partners and also about the relationship, also when making negative judgments , when for some reason its partners do not meet unrealistic expectations (ELLIS AND HARPER, 1961 apud DATTILIO, 2011).

Research indicates that the use of CBT with couples, based on the concepts developed by Beck, has evolved with the application of procedures and techniques that involves the analysis of cognitive processes, emotional and behavioral factors adapted for intervention with couples with marital problems, analyzing the quality of communication and social skills of assertive and positive communication.

In addition, the adoption of cognitive-behavioral methods by couples and family therapists is due, according to Knapp (2004), to several factors, among them are: Research evidence on its effectiveness; its attractiveness to clients who value the proactive approach in problem solving and the construction of skills they can use to face future difficulties and their emphasis on the collaborative relationship between therapists and clients.

It is understood that the therapist, based on the cognitive model, will use several resources within the therapeutic process to seek ways to enable the couple to modify distorted thoughts as well as the set of beliefs that each one acquires in the course of their development and that are sometimes dysfunctional and that cause psychological suffering. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy refers to the principle that the way a person thinks about a particular situation will directly influence how they will feel. Thus, according to your negative or positive beliefs, your automatic thoughts will or will not cause psychological suffering.

It can be understood, based on the studies conducted by Beck (1995), that the main objectives of CBT in the treatment of couples in conflict include the restructuring of inadequate cognitions, the management of emotions, the modification of dysfunctional communication patterns and the development of strategies for solving more effective daily problems, as explained by Peçanha and Rangé (2008).

It should be emphasized that marital conflicts have permeated humanity for a significant period of time, and has also been the subject of studies for decades, as well as the increasing number of couples’ breakups, which has been receiving a diverse look by researchers and scholars on the subject. Therefore, the objective of CBT is to help the couple to expand the knowledge of themselves and to recognize the negative cognitions between cognitions, affections and behaviors aiming at a better form of positive interpersonal relationship.

Therefore, the therapist will seek to favor, through communication training and adequate problem solving, the increase of positive interactions and consequently the reduction of negatives and also agreements on the change of behavior of the partner (EPSTEIN, 1998 apud PEÇANHA E RANGÉ, 2008). Thus, cognitive therapy focuses on how the spouses perceive themselves, positively or negatively, or even what they fail to perceive in the other and also on the way they communicate, whether good or bad or what they fail to communicate (BECK, 1995).

With regard to assertiveness, a factor that matters in the couple’s communication, the author Rangé (2008) notes that assertiveness behavior becomes essential in the conjugal context and communication, as an expression of thoughts, emotions and feelings, are skills that can be learned and become part of the couple’s repertoire of skills, thus facilitating the development of self-knowledge. Cognitive-behavioral interventions aim to restore balance in the couple’s relationship, increasing satisfactory areas and reducing conflicts, working cognitive distortions and communication and problem solving difficulties (OSORIO E VALLE, 2009). Some of the most used techniques are the records of automatic thoughts, a written exercise that enables the couple in the process of identifying thoughts, feelings and behaviors.

It is these components of communication skills that Cognitive Behavioral Therapy proposes to work and in which we seek, in this work, to research from the perspective of couples to be investigated.

4. RESULTS

The results obtained in the research and expressed in numbered Tables and Graphs are presented. The data regarding the sociodemographic profile of the participants in the sample are expressed in Table 01. Regarding education, the interviewees are willing to complete high school (9); incomplete higher education (6); and top complete (5). With regard to the time of marriage from 1 to 10 years (12); 11 to 20 years (4); 21 to 30 years (4). Referring to the number of children, 14 (fourteen) participants have between 0 to 2 children and 6 (six) between 3 and 5 children. The age presented a mean of 30.42 females, with a minimum age of 22 years and a maximum of 44 years and with a standard deviation of 8.23. The male interviewees had a mean age of 28.5, with a minimum age of 25 years and a maximum of 56 years and with a standard deviation of 11.19.

Table 1 – Sociodemographic profile of the sample

| Variable | Levels | Absolute Frequency | Relative Frequency (%) | ||

| Sex | Male

Female |

8

12 |

40

60 |

||

| Schooling | Complete High School

Incomplete Superior Complete Superior |

9

6 5 |

45

30 25 |

||

| Wedding Time (years) | 1 to 10

11 to 20 21 to 30 |

12

4 4 |

60

20 20 |

||

| Number of Children | 0 to 2

3 to 5 |

14

6 |

70

30 |

||

| Average | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum | ||

| Age | Female – 30.42

Male – 28.5 |

8,23

11,19 |

22 years old

25 years old |

44 years old

56 years old |

|

Source: Collection Instrument (2020)

Regarding the questions related to marital social skills to the questions answered in the IHSC inventory (VILLA E DEL PRETTE, 2012), in addition to the results of each item (32) and the general score, which allow a general evaluation of the repertoire of conjugal social skills of the respondent, it still produces five factorial scores resulting from factor analysis that are: Expressiveness/Empathy (F1); Assertive self-affirmation (F2); Reactive self-control (F3); Proactive self-control (F4); Assertive conversation (F5).

These factors are interpreted from the relationship with the sample group of the inventory, in which scores above the 25th percentile and below the 75th percentile are considered, it is interpreted that the respondent has, in a generalized way, a very elaborate repertoire of conjugal social skills in relation to the mean, it is also considered that percentiles below 25, can infer a deficit in the repertoire of social skills and a possible need for intervention. For continuity it is important to understand the meaning of each of the factors evaluated, as described in Chart 1 below.

Table 1: Description of the factors evaluated in the instrument

| Factor | Description |

| F1

Expressiveness/empathy |

It contemplates the skills of expressing understanding, feelings, desires and positive opinions to the spouse, for example: compliments, thanks, well-being, as well as the behaviors of the couple’s intimacies |

| F2

Assertive self-affirmation |

It refers to behaviors of expressing preferences, feelings and opinions assertively towards the spouse. |

| F3

Reactive self-control |

It is related to the behavior in which the spouse seeks to defend himself in situations that are potentially stressful, maintaining self-control and preserving the relationship |

| F4

Proactive self-control |

It deals with the ability of self-control that can be useful for good communication and understanding between the couple. It assesses the respondent’s ability to perceive if the other is emotionally shaken, wait for their turn to speak and make themselves understood. |

| F5

Assertive conversation |

This factor includes requests from one spouse to the other regarding certain behaviors (compliance with agreements, clarifications) and the ability to react assertively to the behaviors of the other, such as: disagreeing or asking others to wait for their turn to speak) |

Source: Research Instrument – Marital Skills (2020)

In factor analysis, the general percentiles of the respondents were compared, primarily in general, where they were divided into: below the mean (percentiles below 25); within the mean (percentiles greater than 25 and less than 75); above average (for percentiles greater than 75). The following results were obtained for the 20 (twenty) participants of both sexes: 12 (twelve) participants are below average with percentiles between 3 and 20, totaling 60%; 8 (eight) participants are within the mean with percentiles between 25 and 60 totaling 40%. The number of both sexes was also obtained, where 12 (twelve) participants are below average, 4 (four) males, corresponding to 33% and 8 (eight) are female, corresponding to 67% and; of the 8 (eight) respondents who are within the mean, 4 (four) are male and 4 (four) female. None of the participants in the total sample had a general percentile above the average, as illustrated in Table 2 below.

Table 2 – Analysis of the general percentiles

| Variables | Levels | Absolute Frequency | Relative Frequency (%) | |

| 03 – 20

25 – 75 75 + (General percentiles) |

Below average

Within the average Above average |

12

8 0 |

60

40 0 |

|

| Sex | ||||

| M

F |

Below average

Below average |

4

8 |

33

67 |

|

| M

F |

Within the average

Within the average |

4

4 |

50

50 |

|

| M

F |

Above average | 0 | 0 | |

Source: Collection Instrument (2020)

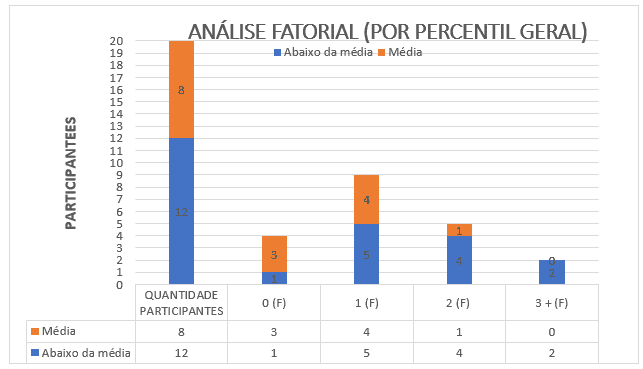

Results and interpretations were obtained from the percentile of each of the five factors evaluated by the instrument, where it is possible to analyze and infer in which factor of marital social ability the participant may have a greater deficit and require a training of skills. The total number of participants by factors, both those that are within the mean and those below the average, in general and of both sexes, were distributed as follows: of the 8 (eight) participants who are within the mean, 03 (three) of these do not present deficit in any factor, 04 (four) present deficit in only one factor , and 01 (one) presents a deficit in two factors. No participant has a deficit in three or more factors. For the 12 (twelve) respondents who are below the average, 01 (one) does not present deficit in any factor, 05 (five) present deficit in only one factor, 04 (four) have deficit in two factors, and 02 (two) have a deficit in three or more factors as illustrated in Graph 1.

Graph 1 – Factor analysis (by general and factorial percentile)

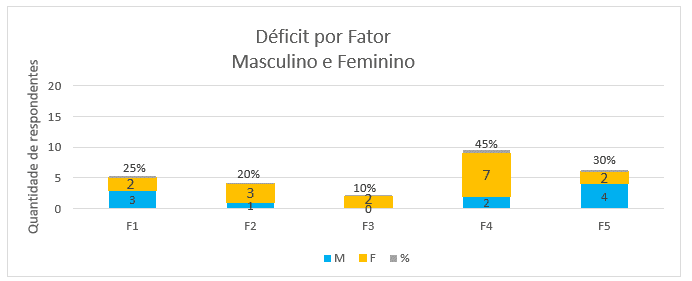

Graph 2 below analyzes the percentiles of the deficit per factor of the 20 (twenty) participants in the research. When comparing both sexes of the respondents, it is obtained that, of these, 05 (five) people had a percentile below the average in the Factor Expressiveness/Empathy (F1) corresponding to 25% of the sample, being 03 (three) male and 02 (two) female; 20% of the sample or 04 (four), two men and two women present deficit in the assertive self-affirmation factor (F2); of the total sample, only 02 (two) females and none of them answered males, which corresponds to 10%, presented deficit in the reactive self-control factor (F3); for the proactive self-control factor (F4) 09 (nine) people presented deficit, equivalent to 45% of the sample, being 07 (seven) women and 02 (two) men; and 06 (six) or 30% of the respondents can infer deficit in the assertive conversation factor (F5), and 04 (four) are men and 02 (two) are women. As shown in Graph 2 below.

Graph 2 – Deficit by Factor of the total sample of both sexes

For the analysis of the results of the factors that had a higher incidence of respondents with difficulties of skilled behaviors, we highlight the factors in decreasing order of percentage and we divided the respondents by gender, which are highlighted in Table 3 where: highlighted is the proactive self-control factor (F4) in which 22% or 02 people are men and 78% or 07 (seven) of the respondents who infer a deficit in these abilities are women; soon after the assertive conversation factor (F5) in which 67% of those with deficit were 04 (four) men and 33% or 02 (two) people were women; and the other with the highest incidence was the Expressiveness/Empathy factor (F1), in which 60% of respondents below the average in this factor are men (03) and 40% are women (02)

Table 3 – Factors with higher incidence

| Variable

Factors |

Levels | Absolute Frequency | Relative Frequency (%) |

| F4

Proactive self-control |

Male

Female |

2

7 |

22

78 |

| F5

Assertive conversation |

Male

Female |

04

02 |

67

33 |

| F1

Expressiveness/Empathy |

Male

Female |

03

02 |

60

40 |

Source: Authors of the research – Incidences in Marital Social Skills (2020)

Each factor is composed of a group of inventory items, in which each participant marks the frequency with which they emit the behavior or feeling referred to in the item in question. Among the factors most frequently, the items that presented the highest frequency of deficient responses of the respondents stand out, according to the number of participants who had a lower score in the said item. These data are best explained in Chart 2 below, where the most recurrent items of each factor are presented. The male (M) and female (F) level and the number (No.) of participants who presented difficulty in the item in question.

Table 2 – Items with higher frequency of deficit responses

| Factor | Items | Level | No. |

| F4

Proactive self-control |

09 – During an argument, when I realize that I am emotionally (nervous) I can calm down before continuing the discussion.

15 – When my spouse speaks in an altered way to me, I hope that he/she will finish what he has to say and then give my opinion 27 – In a situation of conflict of opinion with my spouse, I can make him understand my position. |

MF

M F M F |

17

0 6 1 3 |

| F5

Assertive conversation |

05 – In a conversation, if my spouse interrupts me, I ask him/her to wait until I finish what he was saying

13 – If I do not agree with my spouse, I say this to him/her |

MF

M F |

32

2 1 |

| F1

Expressiveness/Empathy |

01 – On a day-to-day business, I naturally talk about any matter with my spouse.

31 – During sexual intercourse, I usually tell my spouse which caresses I like the most. |

M

F M F |

2

1 2 1 |

Source: Authors of the research – Frequency of behavior/deficit feeling (2020)

5. DISCUSSIONS

Significant results were obtained on the marital social skills in the participants, as well as a parameter of how communication takes place in the conjugal context. In general, in order for good communication to be obtained within interpersonal relationships and for there to be synchronism in this communication process, it is necessary to have socially skilled individuals. The results indicate that women have a greater deficit in proactive self-control and men have greater difficulty in assertive conversation.

In the analysis of the general percentiles explained in Table 2, which give us a generalized description of the repertoire of social skills within the marital context of the subject, subjects below the average, in which a deficit in these skills is inferable, which from the results obtained, it is concluded that 60% of the participants are in some way, with difficulties in the skills that involve communication , emotional expression, as well as empathic action. Godinho (2015) stands out when he states that empathy can be achieved through careful listening about what the other person says and often acquires a broad understanding of the perspective of the other.

These components jeopardize interaction with the spouse and the practical management of marriage such as problem solving for example. In this regard, Caballo (2010) points out that being socially skilled is having a set of behaviors that are issued in an interpersonal context, which express feelings, attitudes, desires, opinions or rights of this individual, appropriately to the situation, similarly respecting this behavior in the other, besides that these skilled subjects, usually solve the immediate problems of the situation, minimizing the probability of future problems.

It turns out that deficient communication is a problem that has been found in couples who, often in an attempt to resolve their conflicts, end up further aggravating the situation, or trigger a new problem. Thus, the lack of communication skills becomes particularly destructive, and can generate, potentiate or maintain marital problems, as Silva and Vandenberghe (2008) explain.

It was possible to notice that women presented greater lack of these skills related to their social behaviors, besides the difficulty of issuing these behaviors in some situations and thus obtaining a desired relationship. It is also a fact that no respondent had a higher-average result, so it is inferable that of the 20 people participating, none has a repertoire, in general, quite elaborate of social communication skills. On the other hand, the 40% that are within the mean present difficulties in some specific factor (Graph 1).

It is noteworthy that social and communication skills between couples are an important factor for marital relationships. It was understood that positive communication generates well-being in the relationship, on the other hand, negative or fragile communication influences the dynamics of the couple and generates conflicts and insatisfações. Thus, couples who, when trying to solve their problems, end up using ineffective communication and end up further aggravating the conflicting situation or may even motivate other problematic situations (SILVA; VANDENBERGHE, 2008).

Therefore, it is important to consider that in the relationship of a couple, communication is incessant and intense, so it is necessary that the couple learn to talk about their way of communication, because otherwise, feelings are being kept and becoming increasingly embedded and, when not expressed, generate non-verbal communications. In this context, everything starts to be communicated in a non-verbalized way, and consequently, the distancing of the couple happens, having difficulty clarifying what they feel, wants or think (ROSSET, 2014).

Among the factors in which the most low means occurred, both of men and women, is the factor that deals with proactive self-control (F4), described in Chart 1, which involves useful aspects for good communication and understanding between the couple. This factor brings related items to make oneself understand and the perception of the other, in the sense of perceiving the emotional change in the partner and as well as knowing that it is time to end a more heated conversation. This social behavior is about knowing how to control oneself in the face of one’s own impulsivity knowing how to act and the right moment to speak. For Peçanha (2005), in the interaction process, the couple may use the words inappropriately, which will hinder the process of assimilation and understanding of what one of the two is thinking or feeling in the face of a specific situation.

It is observed that items 9 and 15, referred to in Chart 2, show us that the incidence is higher in women and not in men, where they presented more difficulties in factors of having self-control in the face of a conflicting situation. Thus, the interruption during the other’s speech, a habit detrimental to the couple’s communication in which the training of stopping the impulse to interrupt the partner’s speech, can lead the person to discover even more of that person with whom he relates. Seeking to deal with anxiety to speak is to have the possibility of self-control in a conversation, is to appropriate sensitivity with the other and allow the person to express himself in the moment of it.

By way of contribution, Rosset (2016) states that many fights are triggered by these compulsions that appear in the relationship and most of these conflicts are maintained by them. On the other hand, men presented greater difficulty in the assertive conversation factor that involves aspects related to reacting assertively to the behavior of the other that can be repulsive at a given moment, which implies making requests to the other that can cause a certain displeasure (for example, asking the other to wait for the end of a speech so that it can thus be pronounced). Assertiveness is in the direct, honest and appropriate expression of feelings, linked to equivalent behaviors (PORTELLA, 2011).

In this direction, Caballo (2010) clarifies that assertive behavior is capable of being learned, thus it is a learning process, until it is more assertive. Thus, behaving assertively, is to directly expose one’s own feelings, needs, legitimate rights or opinions, without offending, hurting and humiliating the other, is manifesting who you really are as a person, with a basic and direct message: That’s what I think! That’s what I feel! Therefore, assertiveness implies declaring their restlessness and feelings without anger or passivity according to Goleman’s position (1995).

From the analysis performed, we bring in counterpoint the factors that stood out in terms of respondents with a repertoire of well-elaborated skills, presented in Graph 2, in which women have a lower index in factor 2 (assertive self-affirmation) referring aspects to know how to express what they prefer, what they feel and how they feel, and their opinion assertively in relation to the partner.

The placements on what the person feels or thinks are more viable, and convey the reality of their feelings, by sequence, the partner will know what their behavior triggers in the other, exemplifying to mention the phrase: I was hurt because you did not arrive at the agreed time to go to the supermarket, becomes more useful than saying: You are completely irresponsible , just thinks and himself and never arrives on time. It is perceived that talking about oneanother and how he feels about such an attitude of the partner is a communication more effective than accusations, because when one arrives with such procedures of blaming the other, the partner will soon act defensively, and with this both will have difficulties to understand each other, as Rosset (2014).

From the analysis undertaken, it was verified that the male sex unanimously presented a well-elaborated repertoire of socially skilled behaviors in the marital context within factor 3 (reactive self-control) presented in Chart 1. They seek to defend themselves in the face of potentially stressful situations, keeping themselves in a controlled manner with the aim of preserving the relationship. In a way that reacts in a more skilled way, in the face of criticism from the partner, and also the know-how to deal with the games. For Del Prette and Del Prette (2008), as competent as the individual is and as good as the intentions are, it is inevitable not to come across people who disprove the way they think and behave and express it through criticism, making it necessary to deal effectively with them.

It is insised that CBT based on the concepts developed by Beck (1995) develops techniques of social communication skills and assertiveness that are used in the treatment of couples. It is perceived that the dysfunctional cognitions, imlogical or distorted thoughts, the dysfunctional beliefs of the conjugue negatively influence the relationship, communication and well-being of the couple. These factors are a source of conflict and disagreement.

Therefore, in CBT with couples, we seek the applicability of techniques such as cognitive restructuring of inadequate cognitions, management of emotions, modification of dysfunctional communication patterns and development of strategies for solving the problems faced by the couple in daily life in a more coherent and effective way, as Dattilio (2010) explains. It is understood that every relationship has its strengths and fragile and the cognitive therapist seeks to reinforce the actions and positive points of the partners so that they have assertive, empathic and warm forms in conjugal interaction.

Finally, based on the data presented here, we agree with the position of the authors described and discussed in the analysis of the research performed, for responding to the proposed objectives. It was possible to understand that conflicts, lack of communication and assertiveness of couples occur in the face of disagreements and different points of view. In the current context, the existing divergences in the couple’s communication involve broader problems, such as the time they spend together, the education of children, tasks to be fulfilled and divided, economic, social, cultural issues, among others. Based on the data presented, they arouse interest and attention to individual characteristics, personality, temperament, self-esteem, empathic communication that influence the positive and negative communication of the couple.

6. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

The present work sought, through a field study, quantitative-qualitative and exploratory to investigate the social communication skills in the conjugal relationship and the contributions of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. We also sought to identify the positive and deficient forms of communication in the marital relationship, and the development of assertive and positive communication.

The results of the study on the participants’ marital social skills were significant. The analysis of the general percentiles explained provides us with a generalized description of the repertoire of social skills within the marital context of the subject. These were below average, with a deficit in these abilities. It was concluded that 60% of the participants encounter difficulties in the skills that involve communication, emotional expression, as well as empathic action.

The results indicate that women have a greater deficit in proactive self-control and men have greater difficulty in assertive conversation. Women report a greater deficit of these aptitudes related to their social behaviors, besides the difficulty of issuing these behaviors in some situations and thus obtaining a desired relationship. The study points out that it is a fact that no respondent had a result above average, so it is inferable that of the 20 (twenty) participants, none has a repertoire, in general, very elaborate of social communication skills. On the other hand, those who are within the mean, which are 40%, present difficulties in some specific factor (Graph 1).

The contribution of Otero and Guerrelhas (2003) stands out, in which they are unanimous in explaining that communication involves one speaking and the other listening, and vice versa. However, when it comes to couples, this everyday situation in people’s lives presents itself with peculiar elements. In addition, in the interaction of the couple there are some behaviors that trigger conflicts in which different authors, among them, Chistensen and Jacobson (2000); Silva and Vandenberghe (2008) call triggers that present themselves with criticism, demand, accumulation of annoyances, sorrows and rejection that somehow trigger disagreements that, in turn, are interpreted and absorbed with suffering and wear.

Regarding the contributions of CBT, the cognitive behavioral therapist will seek to favor, through communication training and adequate problem solving, the increase of positive interactions and, consequently, the reduction of negatives and also agreements on the change in behavior of the partner (EPSTEIN, 1998 apud PEÇANHA E RANGÉ, 2008).

Cognitive therapy focuses on how the spouses perceive themselves, positively or negatively, or even what they fail to perceive in the other and also on the way they communicate, whether good or bad or what they fail to communicate (BECK, 1995). Cognitive-behavioral interventions aim to restore balance in the couple’s relationship, increasing satisfactory areas and reducing conflicts, working cognitive distortions and communication and problem solving difficulties (OSORIO E VALLE, 2009).

The application of CBT in the treatment with couples is effective with the use of cognitive and behavioral techniques among them, the restructuring of distorted cognitions in the face of some situations of the marital context with communication deficit. The goal is to provide the couple with skills that can reduce their conflicts. The couple or partner is led to learn, identify, evaluate and respond to distorted thoughts that negatively influence the relationship. Techniques such as automatic thought recording, descending arrow, socratic questioning, diaries, memories, assertiveness training, dramatizations, among others, are useful and effective.

In the treatment of couples or partners, the behavioral part is relevant with emphasis on communication skills performed through communication training. The goal is to provide the couple with listening and speaking skills that can reduce conflicts and increase marital satisfaction and adjustment, as Rangé and Dattilio (2001) point out.

7. REFERENCES

ALMEIDA, Thiago (org.). Relacionamentos amorosos: o antes, o durante e o depois deles. São Carlos: Compacta Gráfica, 2013. Disponível em <https://www.academia.edu/5773439/Livro_Completo_Relacionamentos_amorosos_o_antes_o_durante…_e_o_depois_Volume_1>. Acesso em: 09 mai 2019.

BECK, A. T.; RUSH, A. J.; SHAW, B. F. & EMERY, G. Terapia cognitiva da depressão. Porto Alegre: Artes Médicas, 1997.

BECK, A. T. Para além do Amor. Editora Rosa dos Tempos, 1995. Disponível em <https://pt.scribd.com/doc/123554870/Para-Alem-Do-Amor-Beck>. Acesso em: 04 jun 2019.

BECK, Judith S. Terapia Cognitivo Comportamental: Teoria e Prática. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2014.

BERTONI, Anna; BODENMANN, Guy. Satisfied and dissatisfied couples: Positive and negative dimensions, conflict styles, and relationships with family of origin. European Psychologist, 15(3),175-184. 2010. IN: COSTA, C. B. da; CENCI, C. M. B.; MOSMANN, C. P. Conflito Conjugal e estratégias de resolução: uma revisão sistemática da literatura. Temas psicol., Ribeirão Preto , v. 24, n. 1, p. 325-338, mar. 2016. Disponível em <http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-389X2016000100017&lng=pt&nrm=iso>.

CABALLO, Vicente E. Manual de avaliação e treinamento das habilidades sociais. São Paulo: Santos, 2010. Disponível em <https://www.academia.edu/9553664/Manual_de_Avaliacao_e_Treinamento_das_Habilidades_Sociais> Acesso em: 5 jun 2019

CABALLO, Vicente E. Manual de Técnicas e de Terapias e Modificação do comportamento. São Paulo: Santos, 2003.

CERVO, Amado Luiz; BERVIAN, Pedro Alcino; SILVA, Roberto da. Metodologia científica. 6. ed. São Paulo: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2007.

CHAPMAN, Gary. As 5 linguagens do amor. 3 ed. São Paulo: Mundo Cristão, 2013

CHRISTENSEN, A. & JACOBSON, N. S. Reconcilable Differences. New York: The Guilford. IN, 2000.

DATTILIO, Frank M. Manual de terapia cognitivo-comportamental para casais e famílias. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2011. Disponível em <https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/0B4cIMwhxIufXaWI0QkVFZ2FaVEU>. Acesso em: 10 maio 2019

DEL PRETTE, Z. A. P.; DEL PRETTE, A. psicologia das habilidades sociais: terapia, educação e trabalho. 5.ed. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2008.

DEL PRETTE, Zilda Aparecida Pereira; VILLA, Miriam Bratfisch; FREITAS, Maura Glória de Freitas; DEL PRETTE, Almir. Estabilidade temporal do Inventário de Habilidades Sociais Conjugais (IHSC). Aval. psicol. [online]. 2008, vol.7, n.1, pp. 67-74. ISSN 1677-0471. Disponível em: http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1677-04712008000100009 Acesso em: 05 jun 2019

FIGUEIREDO, Patrícia da M. V. A influência de locus de controle conjugal, das habilidades sociais conjugais e da comunicação conjugal na satisfação com o casamento. Rio de Janeiro: Ciência e Cognição, 2005. Disponível em <http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1806-58212005000300014> Acesso em: 05 jun 2019

GIL, Antonio Carlos. Como elaborar projetos de pesquisa. 6.ed. São Paulo: Atlas, 2017.

GODINHO, Tânia João Lopes Carriço Gomes. Contributos para a compreensão do processo de empatia e do seu desenvolvimento. Tese de doutorado, Universidade de Évora – Instituto de Investigação e Formação Avançada, 2015. Disponível em <https://dspace.uevora.pt/rdpc/bitstream/10174/14535/11/Doutoramento%20-%20T%C3%A2nia%20Godinho.pdf> Acesso em: 07 jun 2019.

GOLEMAN, Daniel. Inteligência Emocional. Rio de Janeiro: Objetiva, 1995. Disponível em <https://drive.google.com/file/d/1NPm0p1RzqTHN8vT_VXaxyn05fhF0uHQC/view> Acesso em: 20 mai 2019.

HANNS, Luiz. A equação do casamento. Pbook: Paralela, 2013. Disponível em: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/0B4cIMwhxIufXaWI0QkVFZ2FaVEU Acesso em: 10 mai 2019

KNAPP, P. Princípios fundamentais da terapia cognitiva. IN (org). Terapia cognitivo-comportamental na prática psiquiátrica. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2004. (pp 19-41).

MUNDIM, Cleusa Pereira de O. O Papel da comunicação disfuncional no relacionamento de casal. Goiânia: Pontifícia Universidade Católica de Goiás, 2010. Disponível em <https://docplayer.com.br/19265878-O-papel-da-comunicacao-disfuncional-no-relacionamento-de-casal-cleusa-pereira-de-oliveira-mundim.html> Acesso em: 10 mai 2019

OSORIO, Luiz Carlos. Valle. VALLE, Maria Elizabeth Pascual. Manual de Terapia Familiar. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2009

OTERO, V. R. L. & GUERRELHAS, F. Saber falar e saber ouvir: a comunicação entre casais. IN: CONTE, F. C. & BRANDÃO, M. Z. S. (Orgs.), Falo ou não falo? (pp. 71-84). Arapongas: Mecenas, 2003.

PEÇANHA, Raphael Fischer; RANGÉ, Bernard Pimentel. Terapia cognitivo-comportamental com casais: uma revisão. Rio de Janeiro: Revista Brasileira De Terapias Cognitivas, 2008. Vol 4, nº 1. Disponível em <http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1808-56872008000100009> Acesso em: 05 jun 2019

PEÇANHA, Raphael Fischer. Desenvolvimento de um protocolo piloto de tratamento cognitivo-comportamental para casais. Rio de Janeiro: UFRJ/IP, 2005. Disponível em: <http://www.dominiopublico.gov.br/pesquisa/DetalheObraForm.do?select_action=&co_obra=42986> Acesso em 08 jun 2019.

PORTELLA, Mônica. Estratégias de treinamento em habilidades sociais. Rio de Janeiro: Centro de Psicologia Aplicada e Formação, 2011. Disponível em: https://www.academia.edu/37553179/ESTRAT%C3%89GIAS_DE_TREINAMENTO_EM_HABILIDADES_SOCIAIS Acesso em: 08 jun 2019

RANGÉ, B. (org.). Psicoterapias Cognitivo-comportamentais: Um diálogo com a psiquiatria. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2008.

RANGÉ, B.; DATTILIO, F. M. In: RANGÉ, B. P. Psicoterapia comportamental e cognitiva: pesquisa, prática, aplicações e problemas. Campinas: L. Pleno, 2001, cap.15, 171-191.

RICHARDSON, Roberto Jarry. Pesquisa Social. Métodos e Técnicas. São Paulo: Atlas, 1999.

ROSSET, Solange Maria. Brigas na família e no casal: aprendendo a brigar de forma elegante e construtiva. Belo Horizonte: Artesã, 2016.

ROSSET, Solange Maria. O casal nosso de cada dia. São Paulo: Sol, 2014. Disponível em <https://docero.com.br/doc/n51nvs> Acesso em: 28 mai 2019

SARDINHA, Aline; FALCONE, Eliane Mary de Oliveira; FERREIRA, Maria Cristina. As relações entre a satisfação conjugal e as habilidades sociais percebidas no cônjuge. Psicologia Teoria e Pesquisa, Jul-Set 2009, Vol. 25 nº 3. Disponível em <http://www.scielo.br/pdf/ptp/v25n3/a13v25n3.pdf>. Acesso em: 06 jun 2019.

SILVA, Lucilene Prado e; VANDENBERGHE, Luc. A importância do treino de comunicação na terapia comportamental de casal. Psicol. estud., Maringá , v. 13, n. 1, p. 161-168, Mar. 2008 . Disponível em <http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-73722008000100019&lng=en&nrm=iso>. Acesso em: 25 mai 2019 https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-73722008000100019.

SILVA, L. M. G. da; BRASIL, V. V.; GUIMARÃES, H. C. Q. C. P; SAVONITTI, B. H. R. A.; SILVA, M. J. P. da. Comunicação não-verbal: reflexões acerca da linguagem corporal. Ribeirão Preto: Revista Latino-am-enfermagem, 2000. vol 8, n,4. Disponível em <http://www.scielo.br/pdf/rlae/v8n4/12384> Acesso em: 10 mai 2019

VANDENBERGHE, Luc. Terapia comportamental de casal: uma retrospectiva da literatura internacional. Rev. bras. ter. comport. cogn., São Paulo , v. 8, n. 2, p. 145-160, dez. 2006. Disponível em <http://pepsic.bvsalud.org/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1517-55452006000200004&lng=pt&nrm=iso>.

VILLA, Miriam Bratfish; DEL PRETTE, Zilda A. P. Inventário de habilidades sociais conjugais. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo, 2012.

WRIGHT, Jesse H.; BASCO, Monica R.; THASE, Michael E. Aprendendo a terapia cognitivo comportamental. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2008.

[1] Bachelor of Psychology, postgraduate in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy.

[2] Guidance counselor. Master’s degree in Collective Health (UNIFESP), Master’s degree in Educational Sciences (ULHT-Portugal).

Submitted: September, 2020.

Approved: October, 2020.