ORIGINAL ARTICLE

PALLADINO, Ruth Ramalho Ruivo [1], SOUZA, Luiz Augusto de Paula [2], PALLOTTA, Mara Lucia [3], COSTA, Rogério da [4], CUNHA, Maria Claudia [5]

PALLADINO, Ruth Ramalho Ruivo. Et al. Sleep, eat and talk: symbolic enstillment. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 06, Ed. 08, Vol. 06, pp. 153-170. August 2021. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/psychology/symbolic-enstillment, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/psychology/symbolic-enstillment

ABSTRACT

Sleep, food and language are pillars of children’s healthy lives, are intertwined from birth and make up the dynamic structure of child development. These are the effects of interdependent conditions: organic, psychic and social, which involve the child and result, simultaneously, from organic and symbolic inheritances. The latter overdetermines and modulates the interaction of the child with the environment, especially with the other human who is there. This heritage will draw patterns of conduct and behavior that can often contribute to changes that compromise, to some extent, the overall development of the child. In the children’s clinic, the description of developmentdisorders, from the mildest to the most severe, includes, as a rule, food, sleep and language aspects, which suggests, then, a base triad, questioning clinicians as to the possibility of there being, more than a simple coincidence, a correlation between fundamental biological functions. If this is the case, it will be important for the clinician to appropriate this perspective, since the implication will probably determine particularities in the diagnostic and treatment procedures. In this direction, it is worth deepening and discussing the development of these functions (sleep, diet, language), seeking to clarify their constitutive correlation, the link between them.

Keywords: Language, Food, Sleep.

1. INTRODUCTION

Sleep, food and language are pillars of children’s healthy lives, are intertwined from birth and make up the dynamic structure of child development.

Such interlacing, however, is not a unanimous postulate, in the projects for the description and understanding of this triad or each part is taken separately or, then, the privilege of one party over the other is pointed out, that is, they would be relationships that cannot be defined as implication.

To think about the implication it is necessary to assume that sleeping, eating and speaking involve the body, but a body that demands a name, a subjective body and, therefore, a body enlistd by the symbolic: in the linkage of the proper name and the body there is, in the reading of this trait, something that articulates through the appropriation, of itself, which is not such an obvious and simple element in the human constitution (LEITE, 2008, p.16). How is such appropriation of the body represented, which comes from its own body when it is appointed? To name the body is to recognize it in the symbolic field, effect of infinite articulations, actions and intertwined.

Sleep, feeding and speech patterns are effects of interdependent conditions: organic, psychic and social, which involve the child and result, simultaneously, from organic and symbolic inheritances. The latter overdetermines and modulates the interaction of the child with the environment, especially with the other human who is there.

For babies, this environment can be represented, privilegedly, by the maternal figure, the mother and, it is worth noting, it is not even necessarily the biological mother or caregivers, but an asane maternal instance, another human who inscribes the “close-who-help”, the Freudian nebensmench, as Cabassu (2003) explains. The one who, more than guaranteeing the survival of the child’s organism, recognizes it as a subject, constitutes the bond between desire (maternal) and word, from which subjectivity and social relations become possible and begin for the baby, by naming his body and his inscription in a text of affiliation and sociability.

If, as we said, sleep, food and language are pillars of the child’s life, their implication depends, therefore, on the maternal utterances addressed to it, but only if they – to satiate hunger, warm from the cold, pack to sleep… – are accompanied by a non-anonymous desire (STORK, LY, MOTA, 1997, p. 34): this is the presence of the other, the institution of the maternal relationship.

Moreover, it is important to know that it is necessary to recognize in maternal attitudes a cultural sense, equally decisive, because mothers interpret and respond to the manifestations […] of the baby according to the norms of the society to which they belong, even if their answers are also modulated by personal psychic dynamics (CISMARESCO, 1997, p. 267).

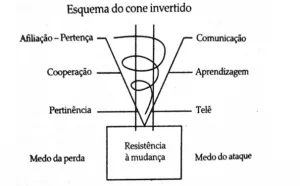

This condition presupposes, more broadly, the centrality of the function of a continent family, for which the concept “I-skin” of Anzieu (1989) can be enlightening, since it refers to the limits between the biological and the symbolic and, for the baby, its establishment responds to the need for a naristic envelope and assures the psychic apparatus the certainty and constancy of a basic well-being (op. cit., p. 44). This feeling of security will be fundamental to the feeling of belonging, basic to the construction of the child’s identity.

This inheritance, at the same time organic and symbolic, transmitted in the child’s relations with the other, allied – of course – to organic inheritance, will draw patterns of conduct and behavior that can often contribute to changes that compromise, to some extent, the general development of the child.

In the children’s clinic, the description of developmentdisorders, from the mildest to the most severe, includes, as a rule, food and sleep aspects (WINNICOTT, 1975; MADEIRA, AQUINO, 2003 ; SANTOS, 2004; JERUSALINSKY, 2004).

The fact that these symptoms are almost always aligned with each other, questions clinicians as to the possibility of there being, more than a simple coincidence, a correlation between fundamental biological functions.

Moreover, in the clinical descriptions of language development disorders, reports of feeding problems (PALLADINO, CUNHA, SOUZA, 2007) and sleep are frequent, which suggests, then, a triad of correlations.

However, and often, the different fields of development study do not share the idea of a significant correlation between such functions, and it is common for sleep, feeding and language issues to be thought separately. When this is the case, in the presence of developmentchanges, the phenomenon is assumed as comorbidity.

There are exceptions and such predominance, it is a fact, with relevance to psychoanalysis and certain approaches of psychology (GROMANN,2002), as well as to the small portion of studies of disciplines that dialogue with both, such as speech therapy, psychiatric medicine, neurology and endocrinology. These exceptions inspired further reflection.

Assuming the correlations between functions makes it possible to clarify the symptomatological alignment observed between eating, sleep and language symptoms in early childhood. If this is the case, it will be important for the clinician to appropriate this perspective, since the implication will probably determine particularities in the diagnostic and treatment procedures.

In this direction, it is worth deepening and discussing the development of these functions (sleep, diet, language), seeking to clarify their constitutive correlation, the link between them.

2. FOOD AND LANGUAGE: THE SURPRISE IN THE OBSERVATION

Some time ago, in the daily life of the children’s clinic, an observation of indicia power began to question us.

This occurred in the face of repeated parental narratives about eating issues in the case-called in evaluation procedures or even in the follow-up of therapeutic plans in the case of children with various language development problems. In dealing with these children, sooner or later, complaints about feeding arose, going from idiosyncrasies to swallowing disorders, and their insistent repetition was what gained place in our clinical listening and, with this, the indicia value of observation gained relevance.

Based on these observations, we structured research with a sample of 35 patients, and the evidence obtained clarified important concomitance between language and eating problems, suggesting a significant correlation between them (PALLADINO, CUNHA, SOUZA, 2004 and 2007).

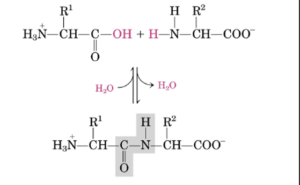

A psychoanalytic reading of the question, offered by the French Journal of Orthophony (2004), allowed us to theoretically coat the results of this research, leading us to think about the correlation between language and feeding problems under the notion of orality, as proposed by Thibaut (2006, p. 115): the oral zone is one of the body egenic zones, that is, a space sustained by a satisfactorily, in which many functions shuffle in the common plane of symbolic functioning. The mouth (organ) is, in this sense, the territory of food, language and affections.

In other words, the oral zone is the somatic field in which orality, as a psychic plane, symbolically interweaves food and language.

3. FOOD, LANGUAGE AND SLEEP: A NEW ARTICULATION

This conceptual repositioning directed and unfolded our clinical listening to other spaces, leading us, more recently, to rework the relationship of food and language from the inclusion of sleep, forming a constitutive triad of the child. Sleep was also included because it is also the protagonist in the fundamental scene of the constitution of the child (PALLADINO, 2016, 2018). Sleep is linked to the baby feeding scene and is part of parental narratives in the case of children with language development problems, although still opaque, that is, considered worthless or with little indicia value in terms of risk to child development.

Assuming the constitutive correlation between these functions, it will be necessary to clarify the symptomatological alignment observed between eating, sleep and language symptoms, as well as to analyze possible implications in diagnostic and treatment behaviors in these cases.

Sleep, a fundamental biological function, important for the restoration of brain energy metabolism and memory consolidation (CABALLO, NAVARRO, SIERRA, 2002), as well as for the psychological balance itself, results from a gradual temporal, structural and physiological organization of the sleep-wake rhythm (GEIB, 2007; PIAULINO DE ARAÚJO, 2012.) It is a state of brain functioning with two different and measurable phases: REM sleep (Rapid Eye Movement) and NREM sleep (No Rapid Eye Movement). The differences are mainly in terms of metabolic mechanisms with consequent changes in physiological processes and postural conditions. In REM sleep, there is an increase in metabolic levels, certain muscle atony, reduction in body temperature, balanced breathing rhythm (with few and brief apneas), rapid eye movements, and in the case of children, crying/smiling/moaning may occur. In NREM sleep there is a decrease in metabolic levels, a decrease in respiratory rate and body mobility (JOHN, 2000). In this phase there is an extensive work of cellular regeneration and in the other, the REM phase, mainly psychological regeneration, as this is where most of the dreams take place.

REM and NREM sleep alternate, as well as sleep and wakefulness states alternate. The cycle between sleep and wakefulness states, at the beginning only biologically determined, begins to be organized still in the fetal phase and its constitution is closely related to the development of the Central Nervous System (GEIB, 2007). Gradually, this organization suffers the impact of exogenous stimuli, such as intense luminosity, varied sounds and, above all, the human presence, causing the sleep-wake cycle to have a rhythm marked by this double interference – endogenous and exogenous.

At birth, the baby’s sleep pattern – essentially physiological – is simpler, with two states, active (REM sleep) and quiet (NREM sleep), in a sleep-wake rhythm called ultradiane, not yet dominated by day-night alternation. The cycles alternate in a shorter time, and in the first months, the active state is predominant: the baby sleeps at any time and wakes up very easily, and the wakefulness is announced by crying and only later is observed the quiet wakefulness. Over time, this rhythm is modified by the environment, causing some anarchic atytyping, that is, changes at the beginning completely disorganized and disorganizing the sleep cycle, not only by the luminous and audible stimuli, but mainly by human action, which ends up modulating the rhythm that, finally, becomes cycardiano, with long night periods of quiet sleep or even quieter wakefulness. (PIAULINO DE ARAÚJO 2012; JOHN, 2000)

A prevalent human action in the issue of sleep of babies is feeding, for two main reasons: it often precedes the moment of the baby sleeping, besides the fact of relying on another human being for its effectiveness. Thus, what at the beginning has a determination only endogenous, begins to suffer influence from the external environment. This is where the ultradianian and cycardianian rhythms consolidate and begin to alternate, the first to govern the distribution of sleep phases and the second the states of sleep and wakefulness, gaining sleep at night and wakefulness the day (PIAULINO DE ARAÚJO, 2012; JOHN, 2000).

By taking the baby in her lap to breastfeed him, the mother offers him an unmatched affective field: the pleasure of sispelling the milk, in hearing the words, in experiencing the rubbing of the body of the other, this delight makes him fall asleep, to give himself.

Sleep and food are thus beyond the record of necessity and, more than that, constitute a definitive intertwining (PENHA, 2002; FÉDIDA, 1977). As mentioned, these functions of the baby depend on another human being for their due realization and, for this reason, gain symbolic character, conforming as psychic experiences. Such experiences, in general of pleasure, leave psychic marks and brain treads, creating powerful memories, which invite the subjects to conviviality with the other.

The mother will breastfeed her baby, speaking and/or singing to him, stroking him, which, along with satiety, quiets the child and promotes sleep. However, hunger will, some time later, awaken the baby, repeating the wake-sleep cycle.

It means that this continuous cycle will not only be an effect of organic rhythm but also of a psychic rhythm, printed by the mother (FARIAS, 2004), through her care.

In other words, the breast (or bottle) becomes a field of exchanges and place of sleep insertion (FOLINO, LOPES DE SOUZA, 2013), talking/humming and packing constitute the ethos of these sleeping practices. Laznik-Penot (1997, p. 37) showed the crucial importance of maternal melopéia – the music of the voice of the mother who talks to the baby. This scene of acalento, in turn, implies food, gives it also symbolic existence.

Ultimately, this intimate and repeated ritual, which involves body and words, sleep and eating, will constitute the fundamental scene of humanization, composing the relational plan in which the bond between the baby and his mother is inaugurated. In fact, this perspective corroborates Spinoza’s ideas (2007) about affections and their consequences in terms of joy or sadness: mother and baby affect and are affected by each other, which makes a network of affective connections that constitute them as such, often expanding the power to act in that singular relationship and in all others. The increased power to act in the world is what Spinoza calls joy.

However, the affections between mother and baby are not always increased in potency, sometimes the opposite can happen. Let’s look at a relatively common example: mothers who go through baby blues (benign depression, transient, potentially productive, because it is part of the changes generated by the coming of a baby) and do not find the possibility of elaboration and acceptance by the social context that often only recognizes the birth of a child by the feelings of happiness and fullness that, culturally, it should produce (FOLINO, LOPES DE SOUZA, 2013).

These depressed mothers spend less time looking, touching, talking to their babies, showing less responsiveness, spontaneity, and lower activity rates with their babies. Postpartum depression contributes to the effect of the dyad becoming asynchronous, to the extent that the mother is little or non-responsive (SERVILHA, RAAD BUSSAB, 2015). During this period, the affective process between mother and baby does not increase the potency of both, on the contrary, it reduces it, and may even unfold, in some cases, psychic issues or disorders for mothers and for the development of the baby. The decrease in the power to act is, in turn, what Spinoza calls sadness.

It is fundamental that the feeding-acarcer-sleep cycle represents varied psychic experiences for the baby, which imply ambiguous senses for the baby: feeding and acarceration become space and time of mother-baby interaction, and the sleep of separation between them – when falling asleep, the baby is placed in the crib. Sleeping will represent a cut, interval or discontinuity in the original link between the child and his mother. The ritual contains, in itself, the ambiguity between acceptance and separation. This position of the mother, double, ambiguous, delicate, is staged when she sings and the child falls asleep to be placed in the cradle: loving approach and separation.

Gradually, the mother spaces the blows – an opportunity to consolidate the waking state – as well as introduce substitutes, which stand between her own body and that of the baby as substitutes for her presence: pacifiers, pans and toys, even the word metaphorical, the one that brings the mother, represents her to the baby. These substitutes are inserted to operate displacements in the fusional relationship that makes up the early days of the mother-baby bond, are supports for the baby to face the anguish of the separation that the sleep announces, the feeling that sleep determines the absence of the mother, deprivation of the environment that assures her life and pleasure.

It should be noted that the need to operate commuting for falling asleep is maintained and updated in adulthood, in the rituals that precede bedtime: baths, teas, readings… . It is as if these rituals remove the “danger” that the loneliness of sleep imposes, and guaranteed a kind of insurance protection for numbness. Several elderly people manifest difficulty in falling asleep by fear of death (GEIB, et al, 2003): anguish of the loss of one’s and the world. The adult has the internalized functioning of the maternal asseguradora instance, operating the displacements, creating the substitutes of the one who was the first guardian of sleep, now unconsciously revived, for example, with massages, sensual practices, ingestion of food, beverages or drugs.

During childhood, in each culture and varying due to social and economic conditions, there are several ways to get around this sleep anguish (by both mother and baby): co-bed (full or partial), shared room and the presence of (necessary) night breastfeeding (BLAIR, 2008).

But, it is important to note, clinicians and researchers tend to refer to the so-called “gold standard” of infant sleep in the western societies so-called developed, a pattern sought early: single bed, separate room from parents, absence of nocturnal feeding.

However, there are different alerts regarding the issue of sleep, as it also imports the participants of the scene and sleep habits, constitutive external of sleep cycles (GEIB, 2007). Minimally, it is assumed that for a child who does not fall asleep or has successive awakenings, there may be a mother who does not think to separate her body from her baby’s body, to stop talking to him, hum for him, to carve him…

One possibility to overcome this anguish is the desire of the dream, an instance in which what was lost or absent can rise onirally.

Initially, the studies postulated that dreams constituted an exclusive activity of the REM phase of sleep. However, more recent research shows that there is no exclusivity, although there is a predominance of this activity in the REM phase, with recognition by scholars that it is intended to ensure that sleep performs its regenerating function (GROMANN, 2002).

Dreams are an effect of the numbness of censorship, which prevent sensations, feelings and actions; censorship that inhabits everyone’s mind, disturbing both wakefulness and sleep itself. The numbness makes room for what is called dreammaking, that is, the construction of thoughts free of interdiction. For this reason, it has been that dreams perform psychic restoration, as important as physical restoration, operated mainly in the NREM phase.

In the child’s development, the phases of sleep are gradually followed to properly organize sleep, making it a canvas for dreams: from physiological to symbolic sleep. The baby needs to build the path between eating, closing his eyes, losing his mother (out of sight!) and meet her again in dreams (PENHA, 2002).

As for sleep, there is a gold standard for food, produced mainly culturally (even if organic aspects are considered there). In the West: breastfeeding for at least six months, natural weaning, introduction of pasty and solids, a path that, quickly, must go from warm liquid, of indefinite taste, to solid, hot, salty food, in familiar scenes involving individual performance.

However, as with the issue of sleep, there are several contents at stake that individualize the scene and deserve attention (JERUSALINSKY, 2004; MADEIRA, AQUINO, 2003).

It is possible to make a parallel and say that for a child who cries, chokes, rumina, vomits and/or refuses food, in addition to possible anatomophysiological problems, there may be a mother who has difficulty positioning herself as the other insurer of the subject in constitution, improperly performing the food scene, without joy or even with sadness.

A metaphorical scene of this difficulty is represented in weaning, a gradual process that deserves delicacy, since it is sustained by symbolic separation operations and, therefore, it is not a “natural” event, obvious, whose supply of food and the passage of certain types to others are always quiet.

4. THE STRINGING OF LANGUAGE

Language is the human action prevalent in sleep and feeding issues. Both functions constitute symbolic experiences in the mother’s words and in the childish words imagined by the mother. In the song, in the story, in the interjections of the mother and in the sugar, in the look, in the close of eyes, in the inarticulate sounds that are the “utterances” of the baby. The dialogical scene is made as a “word game”, in baktinian interpretation. A founding dialogue that persists and marks the subject’s entry into the language, a territory of encounters and confrontations between subjectivities: polyphonic clash of different social instances, conflicting coexistence of voices and effects of meaning. This happens from the beginning, starting from the very polyphony of maternal speech, based in an ambivalent position before your newly arrived baby.

The mother’s speech does not cause a direct effect on her baby, but achieves it through the effect she provoked in herself (CORIAT, 2000), which makes the relationship with the baby a revealing field, which can launch her into an experience of pure pleasure, or not. What immediately focuses on the baby is the mother’s voice, this maternal melody, musical and poetic dimension with affective values (LAZNIK-PENOT, 2013), which involves and sustains the baby, completely dependent. Melody that creates the feeding and numbing scene. The baby holds special attention to the mother’s voice and, in her absence, to any melodic voice that has affections. This is how he composes the interaction with others in his surroundings.

This voice-affection, through subtleties, dynamics and roughness (variation of senses and sensations), is a space for spontaneous expression of the maternal unconscious (FÓNAGY apud LAZNIK-PENOT, 2013). For this reason, it is important to note whether, in this melodic speech, sweet words are produced,or if, from maternal ambivalence, this voice can also produce, in its noises, other (words) very strange (LAZNIK-PENOT, 2013, p. 130). This seems to be a way to understand when the interaction is not successful.

The melodic cradle of the mother’s speech welcomes the baby and throws it into the symbolic dimension of human existence, as Melgaço warns (2013, p.10) when she says that the civilizing process puts the power of words in the spotlight.

To the mother’s voice the baby presents itself with its look, its movements, its sounds, and the back-and-back between the two interaction games are assembled, bathing with words the relationship in which mother and baby are set.

These are primordial constitutive times, in which it is possible to have impasses and, when they hatch, symptoms, expressions that find flow in food, sleep and language, to the extent that these functions concern, centrally, the relationship between the baby and his mother.

To this extent and finally, the core of the issue lies neither in the mother nor in her baby, but in the relationship between them, in a process not of similarity, but of identification, marked initially by the fact that when babies still do not speak, this relational scope is dashed, above all, by the mother’s mental processes, which would be the first time of the constitution of psychic logic and, as Vorcaro (2005, p. 24) points out, from the significant swarm produced in the field of the Other, in which the living being is immersed, the subject’s “previous place” arises as an effect of language. Thus, what remains unconscious in the mother is more susceptible to inscriptions and revelations by the baby (CHAVES, 2013, p. 228).

Sleeping, eating and, why not pointing, the look/being looked at – the baby’s first “words” – are the stage of revelations for the mother and her baby. In this singular relationship, the blossoming of pillar functions of the child’s life will depend on the long path between the position of object (from and to the mother) and that of subject.

5. FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

As stated, this study emerges from the clinic and, we suggest, that it should return to it. That is, in the face of complaints related to sleep, eating and language disorders, it is relevant that the health professional should be able to take care of the possible demands resulting from the symbolic articulation between these three dimensions; articulation inherent to human functioning when the indissociability between language, body and psychism is assumed.

If so, perhaps the dream can also be included in future studies on the intricate symbolic implication worked here.

REFERENCES

ANZIEU, D. O Eu-pele. São Paulo: Casa do Psicólogo, 1989.

BLAIR, O. S. O co-leito em perspectiva. Jornal de pediatria, 84(2), 99-101, 2008.

CABALLO, V. E., NAVARRO, J. F. e SIERRA, J. C. Tratamento comportamental dos transtornos do sono In: CARLSON, N. R. Fisiologia do Comportamento. 7ed, SP: Manole, 2002.

Cabassu G. Palavras em torno do berço. In: Wanderley D. B. (org) Palavras em torno do berço. Salvador, Ágalma, 2003.

CHAVES, M. P. C. T. O lugar do analista na clínica com bebês. In: BUSNEL M. C. e MELGAÇO R. G. (orgs) O bebê e as palavras: uma visão transdisciplinar sobre o bebê. Instituto Langage, 2013.

CISMARESCO, A. S. O grito neonatal e suas funções. (seção: o grito e as reações fisiológicas e emocionais das mães). In: BUSNEL, M. C. A linguagem dos bebês. São Paulo, Escuta ed., 1997.

CORIAT, E. Os flamantes bebês e a velha psicanálise. Estilos da Clínica. V.5, n.8, 2000.

FARIAS, C. N. F. e GOMES DE LIMA, G. Relação mãe-criança: esboço de um percurso na teoria psicanalítica. Revista Estilos da Clínica, ano IX, n. 16, 2004.

FÉDIDA, P. Le conte et la zone de l’endormissement. In: Corps de vide et espace de séance. Paris, Jean Pierre Delaye, 1977.

FOLINO, C. S. G. e LOPES DE SOUZA, AS. As Reverberações do encontro mãe-bebê: sobre a depressão e a depressividade pós-parto. In: BUSNEL, M. C. E MELGAÇO, R. G. (orgs) O bebê e as palavras: uma visão transdisciplinar sobre o bebê. Instituto Langage, 2013.

GEIB, L. T. C., CATALDO NETO,A, WAINBERG R, NUNES ML. Sono e envelhecimento. Rev. Psiquiatria. Rio Gd. Sul, 25(3):453-465, 2003.

GEIB, L. T. C. Desenvolvimento dos estados do sono na infância. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 60(3):323-26, 2007.

GROMANN, R. M. G. Sonho e psiquismo: o labirinto entre o corpo e a subjetividade. Pulsional Revista de psicanálise, 164: 27-34, 2002

JERUSALINSKY, A. Psicanálise e desenvolvimento infantil. Porto alegre, Artes e Ofícios, 2004.

JOHN, M. W. Sensitivity and specificity of the multiple sleep latency test (MSLT), the maintenance of wakefulness test and the Epworth sleepiness scale: failure of the MSLT as a gold standard. J. Sleep Res, 9: 5-11, 2000.

LAZNIK-PENOT, M. C. Rumo à palavra. São Paulo, Escuta ed., 1997.

LAZNIK-PENOT, M. C. Linguagem e comunicação do bebê de zero a três meses. In: LAZNIK-PENOT, M. C. A hora e a vez do bebê. Instituto Langage, 2013.

LEITE, C. A. O. Quando o corpo pede um nome. Tese de doutorado, Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem, UNICAMP, 2008.

MADEIRA, I. R. e AQUINO, L. A. Problemas de abordagem difícil: “não come” e “não dorme”. J Pediatr, 79 (Supl 1): 43-54, 2003.

MELGAÇO, R. G. Prefácio. In: BUSNEL, M. C. e MELGAÇO, R. G. (orgs) O bebê e as palavras. São Paulo, Instituto Langage, 2013.

PALLADINO, R. R. R.; CUNHA, M.C. e SOUZA, L. A. P. Transtornos de linguagem e transtornos de alimentação em crianças. Revista Psicanálise e Universidade, 21: 95-108, 2004.

PALLADINO, R. R. R.; CUNHA, M.C. e SOUZA, L. A. P. Transtornos de linguagem e de alimentação: coincidências ou co-ocorrências? Pró-fono Revista de Atualização Científica, 19, 205-214, 2007.

PALLADINO RRR. Linguagem e sono. Anais do XXIV Congresso Brasileiro de Fonoaudiologia, Sociedade Brasileira de Fonoaudiologia, São Paulo, 2016

PALLADINO RRR. Sono e alimentação: funções psíquicas associadas. Anais do III Congresso Iberoamericano de Fonoaudiologia e XXVI Congresso Brasileiro de Fonoaudiologia. Sociedade Brasileira de Fonoaudiologia, Curitiba, 2018.

PENHA, N. C. G. Dormir nos braços da mãe: a primeira guardiã do sono. Rev Psichê, 6(10):65-84, 2002.

PIAULINO DE ARAÚJO, P. D. Validação do questionário do sono infantil de Reimão e Lefèvre (QRL). Tese de doutorado, Departamento de Neurologia, USP, 2012.

RÉÉDUCATION ORTHOPHONIQUE, 44 année, juin/2006, trimestriel n. 226 – La deglutition Dysfunctionnelle, 2006.

SANTOS, M. C. Problemas alimentares da infância sem diagnóstico clínico: quando vigiar, quando atuar? Rev. Hospital de Crianças Maria Pia, vol. XIII, n.4: 342-7, 2004.

SERVILHA, B. e RAAD BUSSAB, V.S. Interação Mãe-Criança e Desenvolvimento da Linguagem: a Influência da Depressão Pós-Parto. Psico, Porto Alegre, v. 46, n. 1, pp. 101-109, jan.-mar. 2015.

SPINOZA, B. Ética. Trad. e notas de Thomaz Tadeu. Belo Horizonte, Autêntica Ed. 2007.

STORK, H.; LY, O. e MOTA. G. Os bebês falam: como você os compreende? Uma comparação intercultural. In: BUSNEL, M. C. (org) A linguagem dos bebês. Sabemos escutá-los? São Paulo: Escuta Ed., 1997.

THIBAULT, C. A língua, órgão chave das oralidades. Rééducation Orthophonique, 44 année, juin/2006, trimestriel, n.226 – La deglutition Dysfunctionnelle, p.115, 2006.

VORCARO, A. Crianças em Psicanálise, Rio de Janeiro, Companhia de Freud, 2005.

WINNICOTT, D. W. Pensando sobre crianças. Porto Alegre, Artmed, 1975.

[1] PhD in Clinical Psychology, PhD professor of the Graduate Program in Human Communication and Health, Faculty of Human ities and Health, PUC-SP (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8466-838X).

[2] PhD in Clinical Psychology, full professor of the Graduate Program in Human Communication and Health, Faculty of Humanities and Health, PUC-SP (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4968-9753).

[3] PhD student in Human Communication and Health at PUC-SP (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5986-9657).

[4] PhD in Philosophy, PhD professor of the Graduate Program of Communication and Semiotics, PUC-SP (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6807-4263).

[5] PhD in Clinical Psychology, full professor of the Graduate Program in Human Communication and Health, Faculty of Human ities and Health, PUC-SP (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3198-6995).

Submitted: September, 2021.

Approved: September, 2021.