ORIGINAL ARTICLE

PEREIRA, Tulio Augusto de Paiva [1], BAZON, Sebastião Donizeti [2]

PEREIRA, Tulio Augusto de Paiva. BAZON, Sebastião Donizeti. The evangelizing action of the Jesuits, the Colonizer Portuguese and the Indigenous Culture and Civilization in Colonial Brazil. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. 04 year, Ed. 07, Vol. 12, pp. 82-118. July 2019. ISSN: 2448-0959. Acess Link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/history/acao-evangelizing

SUMMARY

The Society of Jesus, through the Jesuits, arrived in Brazil in 1549 together with the first Portuguese colonizers. He actively participated in the process of colonization of the country, leaving his mark on history and greatly influencing the Brazilian cultural formation. Such participation, according to historians is quite controversial, because some authors exalt their work, placing religious as true saints, protagonists of miracles, protectors of the Indians and their culture, skilled educators and writers, among many praises; other authors accuse them of being responsible for the imposition of European culture on Native Brazilians, actively contributing to the destruction of their cultural identity and, consequently, to the near extinction of the Indians as a people in our country. This work aims to review, analyze and evaluate part of the available bibliography on the subject, discussing this issue, that is, to what extent the Jesuits in their evangelizing action in Brazilian lands were responsible for the “destruction” of the Indian and their culture. However, in relation to this problem, the analysis of the figure and the action of the colonizer Portuguese, who, for the most part, came to Brazil with the sole objective of enriching, often acting unscrupulously in this sense, seeing the Indian only as a means (slave labor) to achieve his intention or, otherwise, as a nuisance in his conquests , and should therefore be expelled from the area or simply disposed of. Thus, it is clear, through the development of this work, that if it were not for the action of the Jesuits, even with all their “sins and mistakes”, the Indian would have been exploited and, perhaps, exterminated in a much faster and more violent way.

Keywords: Jesuit, Indian, colonizer, war, destruction.

INTRODUCTION

The objective of this work is to discuss the evangelizing action developed by the Jesuit religious with the Indians in Brazil at the time of the colony, together with the colonization project implemented by Portugal and, consequently, from this analysis, evaluate the extent to which these actions were decisive in the practically destruction of the Indian and its culture in Brazilian lands as it was often and still continues to be placed by several historians and authors.

To what extent has the Jesuit action really contributed to this genocide? According to Asunción (2003, p.11) “the main objective of the Society of Jesus was to convert the indigenous to the Catholic faith”; also according to Asunción (2003, p.23) this goal was to “bring the lost sheep (the Indians) into the herd of Christianity”; but how did this interaction – Jesuits/indigenous peoples – take place in practice?

What about the colonization project? According to Koshiba (1994, p.40), the Portuguese “arrived, appropriated indigenous lands, took their wives, demanded work and considered themselves their natural masters”; the Portuguese thought themselves to be superior beings and natural owners of the new lands by right.

Thus, from the placement of these questions, this work of eminently theoretical nature was developed, based on the existing bibliographical research on the subject.

The work is divided into four parts: the first part aims to study the Jesuits and the institution to which they were linked, the Society of Jesus; analyzing its performance and its history from the foundation to the present day; the second part approaches the Brazilian Indian with his way of life, his customs and his culture; the third part deals with the colonizer Portuguese, showing a part of his history and analyzing the reasons that led him to come to Brazil and explore the new world; finally, the fourth and final part of the work studies and analyzes the various faces of contact between these three elements – the Jesuit, the colonizer Portuguese and the Indian – and its consequences, especially for the Indian.

The proposal is to study and know these three elements individually, and then analyze their participation in the colonization process, verifying how they acted in the face of violence against indigenous tribes and their culture.

1. THE JESUITS

In order to understand the relationship of the Jesuits with the indigenous question in the period of colonial Brazil, it is necessary to know what the Society of Jesus was throughout its history throughout the world, to know its areas of influences in the various sectors of human life, to know its main personalities and its achievements, in addition to its deviations and its ills.

Wright (2004, p.12) in his book “The Jesuits”, summarizes very well the role of the Society of Jesus in the history of mankind, stating that this institution became from its foundation, from the beginning, into the “most vibrant and challenging religious order that the Catholic Church had produced”, revealing itself “a powerful force in the classroom, in the pulpit, in the confessional , in the laboratory, observatory, halls, academia and in the highest bastions of public power”. Also, according to Wright (2004, p.16), for five hundred years they have participated in a turbulent and influential way in the history of humanity, having fulfilled, over time beyond the functions of evangelizers and theologians, other activities such as: those of urban courtesans both in Paris and in Beijing and Prague, saying, at various times, to kings when and with whom to marry or when and how to go to war; serving as astronomers for Chinese emperors or for chaplains of the Japanese army; instructing great men from various areas such as “Voltaire, Castro, Hitchcock and Joyce”; in addition, “they raised sheep in Quito, they also owned haciendas in Mexico, wine producers in Australia and farmers in the United States”; produced works in the fields of letters, arts, music, science, dance, as well as theories in relation to diseases, laws of electricity, optics; confronted the “challenges of Copernicus, Descartes and Newton”; finally, not to extend the variety of their activities, they were recognized for their contributions in the field of knowledge, with no fewer than thirty-five craters on the surface of the moon named after Jesuit scientists.

Complementing the information about the Activities and importance of the Company to humanity, Strieder (2009) says that jesuits around the world were obliged to send detailed reports of their activities, indicating the problems faced and the successes obtained, to the Superior General of the Order in Rome, and, these reports written often in the form of books and chronicles have become and are to our day , a source of research for ethnologists and historians on the events related to the colonial period from the 16th to the 18th century. According to Wright (2004), it was through the Jesuits that Europe learned reports of new cultures, rivers, stars, animals, plants and drugs – from “camellias to ginseng and quinine”. It was they who located the source of the Blue Nile, found land routes connecting Mmosk to China and cartography of the expanses of the Orinoco, Amazon and Mississippi rivers. They also took “the snuff and the works of Aesop and Galileo to Beijing, coffee to Venezuela, and Kepler’s laws of planetary movement for Indian astronomy.”

Continuing, Wright (2004, p.17) states that, despite all this presence and influence in the most diverse sectors of human life, the Jesuits made many enemies who appointed them “as murderers of kings, poisoners or practitioners of black magic”, as well as “providers of moral advice of an absurd permissiveness, depraved, miserly salafários who exploited secret gold mines and stripped rich and naïve widows of their inheritances”. Self-proclaimed defenders of intellectual freedom, but often characterized themselves as true “unconscious automatons, who were loyal to their superiors without questioning.” They had a unique ability “to promote themselves, generate theologies and spiritualities”, in addition to “training, organizing and motivating their vast and versatile workforce”, in addition to the workforce of the faithful and Indians for their own benefit, always leaving the doubt, according to the author, that all this “virtuosity would have been a blessing or a plague”.

Among the declared enemies of the Jesuits, according to Wright (2004, p.18-20), were the “Protestants of the Reformation, 18th-century philosophers and 19th-century liberals,” and nothing less than Napoleon Bonaparte and Thomas Jefferson, among others. The Society of Jesus was not created as a Catholic reaction to the Reformation, but would soon become his right-hand man in the fight for counter-reform in the “Americas (from Canada to Brazil), Africa and Asia (from the Congo to the Philippines)”. From the 18th century on the back of the Enlightenment theories, it would culminate in national bans in many countries and widespread repressions around the world. Finally, in the contemporary era, “the Company would confront the deeds and legacies of Marx, Darwin, Freud and Hitler and seek to redefine the Catholic Church.”

Wright (2004) concludes by stating that both hagiography – which catalogs the lives of martyrs considered saints – and black legends about the Jesuits are, in a way, exaggerated, because there were good and bad religious, and some entered the order to actually serve Christ, others to serve themselves and advance their careers. The history of the Jesuits is neither unanimous nor unique, however, the myth and the contradiction was created about them, dubious caricatures, sometimes placing them as criminal priests, sometimes as sanctified heroes; praise and condemnations of the most diverse are constant, however, the way the Jesuits entered and went out of fashion, marks the essence of the Company.

Raised these observations, so well elaborated by Wright in his work “The Jesuits – missions, myths and stories” and that clearly define the various faces of the work of the Jesuit order throughout the world, we can better know the history of the Company from its emergence, its suppression and its rebirth, and thus know its relationship with the history of the Indians in Brazil.

According to Asunción (2003) in his work “The Jesuits in Colonial Brazil”, the first informal step towards the formation of the Society of Jesus was taken by Ignatius of Loyola on August 5, 1534, when he made in Montmartre the vows of poverty, chastity and obedience to the Pope. Loyola was the founder and the first Superior General of the Order – the highest position within the institution – leading her to her death in July 1556. But according to Wright (2004), the official recognition of the Company would only take place in September 1540 with the bull of Pope Paul III – Regimini militants ecclesiae. For his work, Ignatius of Loyola was beatified by Pope Paul V in 1609 and canonized by Pope Gregory XV in 1622. (ASSUNÇÃO, 2003).

Asunción (2003) also states that the Society of Jesus organized itself following a centralizing hierarchy, according to a model of military structure, where novices referred to the brothers who obeyed the priests and they followed the orders of the superior priests. The highest position within the institution was the general priest, elected by the General Congregation, the only existing legislative authority.

According to Asunción (2003), the formation of a Jesuit began with the novitiate for a period of two years, this phase ended with the confirmation of his vocation and the vows of perpetual poverty, chastity and obedience. A second phase of Jesuit formation was that of the Coadjutors, who could be of two types: temporal that assisted in external activities, and spiritual, which were priests. The spiritual Coadjutores deepened their theological studies in ordering them as priests, when they then made their solemn vows to live and die in the Company, serving God and helping others, and from there they could be sent to work anywhere in the world in the interest of the Institution.

Asunción (2003) also says that another great name of the Society of Jesus was Francis Xavier, sent by King John III, King of Portugal, to Portuguese lands in the East in 1541, having become one of the first martyrs of the Company, preaching in India, the Moluccas and Japan, died in 1552 and, after being declared holy by Pope Gregory XV in 1622 , had its worship spread within the Company itself, with its image, together with that of St. Ignatius of Loyola, was venerated in all the colleges and churches of the institution. According to Strieder (2009), one of The Ignatius of Loyola’s greatest teachings to his command, which served as a motto and warning to the order, always being in evidence in his dependencies, was always to evaluate people for what they do and not for what they say.

It is also worth mentioning, the work of two Jesuits who worked in Brazil, they were Father Manoel da Nóbrega – leader of the Jesuits in the colony – and José de Anchieta. The two are responsible, among other achievements, for the foundation of the village of São Paulo on the Piratininga plateau in 1554, there installing the Jesuit College; in addition to the work developed in the protection and catechesis of indigenous peoples. (FAUSTO, 2009). In the literary field, Anchieta was responsible for the elaboration of the first Tupi-Guarani grammar, while Manoel da Nóbrega wrote several letters to his superiors in Europe in which he narrated the routine of the colony and the Indians; these letters would become historical documents, as already mentioned above. Still in the literary field, according to Asunción (2003) deserves to highlight the work of Father Antônio Vieira, praised by Fernando Pessoa who called him “emperor of the Portuguese language” for having been a great speaker and preacher of several sermons on public issues and personal counseling.

But, returning to the times of Protestant reform, a time of great questioning regarding the dogmas and practices of the Catholic Church, according to Asunción (2003, p.6), “the Society of Jesus arose, thus, with the aim of defending and spreading the Catholic faith throughout the world”, reforming and renewing traditional Catholicism, fighting Protestantism and confirming the doctrinal and spiritual authority of the clergy. According to Wright, (2004), Protestantism was regarded within the Church as a “disgusting cesspool” from which all the ills within Christianity had arisen, the so-called heresies which, “like a fever, had to subside”; “like excrement, it had to be evacuated”; or “as a hormonal imbalance, had to be adjusted”. The Jesuits as the “spiritual doctors” had to “administer the antidote or purgative” using the full range of remedies and procedures, some bitter and violent, “aimed at cauterization and healing”. Thus, according to Asunción (2003), the Jesuits also played important roles in the Courts of the Inquisition, because, among their functions, they had to act in the renewal of the Church and in the fight against heretics.

Strieder (2009) states that the Jesuit should be a reliable person, not requiring control in the development of his activities; he should have the wisdom to discern and choose, according to the place and time he was in, the best attitude to be taken in order to always attain the “greatest glory of God”; it should thus be able to make decisions, but periodically account for its attitudes to its superiors; he should always be united with his companions, always avoiding indiscipline and internal disagreements; Christianity and the Church for the Jesuits should be transnational and cross-cultural. According to Strieder (2009), based on the words of Jesus Christ – “go to all peoples, making them my disciples and baptizing them” – the Jesuits should “Christianize the world”; this orientation conditioned all Jesuit action. Some attitudes, still according to the author, the order universalized, such as: humanistic and literary formation, knowledge of the languages and customs of the peoples with whom it lived, acculturation to these customs when they did not contradict their Christian principles and, attempt to change customs when considered corrupt and perverse.

Strieder (2009) also says that the Jesuits were very close to kings and princes and they provided them with the important resources necessary for their activities: financing their schools, taking them on their mission trips to the missions, granting land to their farms and villages of Indians and protecting them from the threats of settlers and hostile Indians. The Jesuits were always with governors in the foundation of new cities, in the fight against invaders, in appeasement and in the protection of the Christianized indigenous. However, against the indigenous anthropophagus, polygamous and hostile, they defended the “just war” with their enslavement and death.

Asunción (2003) says that the Society of Jesus differed from the other orders at the time, by refusing to be isolated from society, in addition to its members criticizing the prevailing corruption within the Church with the sale of indulgences and the disrespect of the vow of chastity. In this sense, Wright (2004) states that in the first hundred years of its history, the Company’s success went far beyond its acclaimed ability to oppose the Reformation. Within the educational, scientific, political and evangelizing spheres, an innovative and ambitious multinational organization has made spectacular feats, and this vigor and versatility have pleased and disrupted Catholicism more or less in equal measure. For this reason, according to Wright (2004), the Jesuits encountered great enemies within the Catholic Church itself, including with national rivalries within the order itself, where Portuguese Jesuits stood against Spanish, French or Italian Jesuits and vice versa, or even Jesuits born in the colonies stood against Jesuits born in Europe. Wright (2004) states that these rivalries have undermined both the internal politics of the order and its missionary effort over time.

Throughout the 17th century, the most significant issue faced by the Catholic Church and the Society of Jesus, according to Wright (2004), was French Jansenism, with the anti-Jesuit myth becoming increasingly important because of ordinary propaganda and a serious and intelligent theology meeting, but it was a conflict that always came to gross exaggeration and political maneuvering. The most significant production, however, somewhat picturesque, of this current was Blaise Pascal’s “Provincial Letters”, which satirized in a biased and subtly perverse way the idea of the corrupt and corrupting Jesuit casuistry, a notion that penetrated the popular imagination from then on and never changed.

Already in the eighteenth century, the Enlightenment, with its vision that favored reason over superstition, crendices and dogmas, attacked Rome and consequently everything that was linked to religiosity, including the Jesuits. However, there was, according to Wright (2004), a unified enlightenment of hatred of priests, but rather several “national Enlightenments”, many of which could not be seen as anticlerical, as they shared an intellectual method greatly influenced by a Christian past; the greatest criticism came from the noble halls of Paris and Vienna, but it was not shared so vigorously throughout the movement. Not to mention that many Jesuits valued the role of reason in spiritual life, seeing it as a tool with which belief could be expanded through the valorization of an Enlightenment of faith; many clerics, including Jesuits, used the much-known theories of Newton, Wolff, and Leibniz and were happy to employ the philosophical and scientific obsessions of their time to defend and revitalize Christianity. Thus, irony prevails, because “with all the differences between the Company’s perspective and the anticlerical inclination of some Enlightenment figures, their worldviews could be incredibly similar”: “an optimistic view of humanity’s capacities, a vigorous emphasis on the free will of men, an unwavering faith in the transforming power of education”; “such characteristics are often presented as a summary of the Enlightenment project, but they also closely resemble that of the Jesuits.”

Strieder (2009) recalls that the Jesuit work on paraguayan reductions, which received several denominations (“Republic of the Indians”, “Sacred Experiment”, “Exemplary Christian Republic”, and “Communism of Primitive Christianity”, among others) fascinated Enlighteners, socialists, poets, historians, faithful and infidels, inspiring a vast and rich literature with various comments and analyses. Voltaire, for example, admired this Jesuit work, which he said had the merit of submitting indigenous peoples for instruction and persuasion and not for the cruelty and violence of weapons. Montesquieu, Diderot and Abbot Reynal also speak positively of the Jesuit experiment. In relation to the history and ideas of European socialism, the Mission experiment also exerted a strong influence, because in the 19th and 20th centuries, many reformers of the agrarian system defended the system of distribution and collective use of land, in addition to the means of production practiced in the Reductions.

But by the 18th century, according to Wright (2004), missions were already weakened in China, Canada, and India; the anti-Jesuit propaganda machine was also growing stronger, culminating in August 1773 with the extinction of the entire Company through the papal brief suppression of Clement XIV. The problem began in Portugal as early as 1755 at the time of the lisbon earthquake, with some Jesuits clumsy enough to describe the tragedy as a divine punishment for Portuguese sins, causing a tremendous malaise in all spheres of Lusitanian society in the face of such derision. According to Asunción (2003), later the Guaranitic Wars took place from 1754 to 1756, with the Jesuits accused of inciting the villaged Indians to war against metropolitan forces in opposition to the resolutions of the Treaty of Madrid signed between Portugal and Spain to define border issues in the South American colonies. Other issues of insubordination of the Jesuits to both Portuguese laws and the pope’s determinations also eroded relations with the Portuguese crown. Finally, in 1758 the situation worsened with the suspicion of participation of Jesuits in an assassination attempt on King José of Portugal. Wright (2004) says that there was also the issue of the supposed hidden Jesuit wealth and the rivalry between the jesuit economic enterprises with the Portuguese commercial company of the Marquis of Pombal. Thus, according to Asunción (2003), in 1759, D. José I, king of Portugal determined that the religious be expelled from Portugal, Brazil and the other Portuguese lands breaking with a union of more than two hundred years between the Company and the Portuguese Crown. This resolution aimed to preserve the real authority and sovereignty of the Lusitanian State, maintaining the harmony of society threatened by the power and interference of religious in state affairs.

Strieder (2009) says that at that time was created and sponsored by the Marquis of Pombal an anti-Jesuit propaganda so fierce, that some of his propositions have repercussions to this day on the mentality of many Brazilian scholars and historians. These ideas, often unfounded, aiming to serve only political interests, are propagated in schools and in scientific works, eventually negatively influencing the judgment made of the activities of the Society of Jesus.

After the events in Portugal, France, where there was already a great resistance to the Jesuits, they were accused of murderers, sorcerers and shameful moral advisors. According to Wright (2004) no one would know how to define what crime the Company had committed, but even so the order was condemned, being dissolved in November 1764 throughout the kingdom, through a reluctant edict of King Louis XV. Next, the same would happen in Spain; then in Naples, Parma and Sicily, idem. Rome was under pressure and with the death of Pope Clement XIII, the conclave established to elect his successor was dominated by the issue of suppression defers the election of Benedict XIV by six months.

According to Wright (2004, p.209-210), “for monarchs it was easy to believe that the Roman Church represented a rival center of power and influence in their domains”, after all “they were educating populations, directing their consciences, imposing social and moral rules, while at the same time enjoying substantial legal and economic privileges.” In all the countries in which she worked, the Church was able to gather a large portion of the national wealth. Still according to Wright (2004) the Company was not a mendicant order and sought to finance its evangelism through a very dynamic chain of commercial activities, such as: banking institutions, mining, real estate business and involvement in the spice and silk trade, among others. Their commercial profits, even when originating in morally debatable activities such as the production of alcoholic beverages or the exploitation of slave labor were always reinvested in the Priesthood of the Company.

Wright (2004) says that “the strange thing about the disappearance of the Society of Jesus was that the order never disappeared entirely.” In 1814, the Jesuits completely resurfaced, the papal bull of the restoration of the Company claimed that the Catholic world demanded it unanimously. But that was not quite the truth, because at that time there was still no shortage of Anti-Jesuit Catholics. On this issue of the non-total suppression of the Society of Jesus, Strieder (2009) cites that in Russia of the Orthodox Church, Catherine II did not allow the papal decree of suppression of the Order to be disclosed, so there continued working about 200 Jesuits.

The thinkers of the 19th century, Marx, Feuerbach and Nietzche denounced religion and Catholicism “as a plague, an illusion created by man, undoubtedly as an evil.” (WRIGHT, 2004). Catholics really had to formulate great responses to the challenges of this century by enduring insults, scattering and violence beyond revolutionary terror. (WRIGHT, 2004). “The history of the Jesuits in 19th-century Europe” was “an effort to rescue the influence of an earlier era and at the same time face an endless stream of setbacks.” (WRIGHT, 2004, p.228). “Events as widely disparate as the first Socialist International meeting in 1864, the Franco-Prussian conflict of 1870-71 and the Boer War would all be associated with the Company.” (WRIGHT, 2004, p.239).

In the 20th century, the omission of a large number of Catholics, including Jesuits, in the face of the atrocities of Nazism stands out. (WRIGHT, 2004). But what marks this century for the Company is the definition of justice as a new cry for Jesuit reunification through the “Liberation Theology” that preaches not only the deliverance from sin, but also poverty and social injustice. New irony of fate when the Jesuits, a century later, use “Marx to understand and denounce iniquity.” (WRIGHT, 2004, p.273). In conclusion, today the commitment to justice is as important to the Jesuits as their struggle against the Reformation or evangelization was for their predecessors and, it is in this collision between tradition and contingency that lies the fascination of Jesuit history. (WRIGHT, 2004).

Reaching the present day, in 2003 there were about 20,500 Jesuits worldwide, and currently, according to Wright (2004), they can be found in almost all countries and in almost every type of workplace, whether in war zones or troubled places in the world, such as Sudan, Angola, Rwanda, Timor-Leste, Balkans, Moluccas, the probability of Jesuit presence is high. There are biochemical Jesuits, responsible for retreat houses, teachers in business schools, one who took over a position of director of Disney, who gave up a chair in the American Congress, among many other curious cases around the world, and even the current pope comes from the Jesuit ranks.

Before finishing this part of the work, another theme that greatly affects the religious of the Catholic Church nowadays and could not fail to be mentioned in this study is the sexual issue involving them. According to Wright (2004), since the beginning of their history, the Jesuits have often been accused of masters in the art of seducing beautiful young women, of being brothel regulars, maintainers of lovers for their enjoyment, also accused of maintaining a close connection between confessional and sex; his conduct in this area was also questioned within schools in relation to pedophilia and homosexuality. But the deviant conduct of some members of the order, as it is today with the Church and other institutions, cannot tarnish the image of the whole congregation. Bad elements existed and exist in all institutions, whether religious or not, but what was not and today also does not exist within the Church, was an effective system of investigation, trial and punishment for those who deviated in their conduct. Corporatism and “blind eye” were stronger and more active than any initiative to moralize the institution in this field, as well as in other controversial situations involving the Society of Jesus and its members.

To understand the work of the Jesuits in Brazil at the time of colonization, it becomes important, as stated earlier, to know their history. As discussed in this chapter, this story is very rich and comprehensive, full of ups and downs, with acts of courage, bravery, selflessness, true surrender and giving to God’s designs, but also acts of exploitation, of crimes, of complete distortion to what is preached in the gospel. In Brazil it was not very different, as will be seen in the fourth chapter of this work.

2. THE INDIANS

In relation to the Brazilian Indians, according to Bueno (1997), talking about their origin, what is known to this day are only uncertainties. Several theories were launched, reporting on the arrival of man in the territory that is now called Brazil: the most accepted defends the migration of man via bering strait at the time when there was an ice bridge in that place uniting Asia to North America. According to Koshiba (1994), this would have occurred from 35,000 years to 12,000 years before Christ; from that period the temperature would have risen and dismantled the ice bridge. There are other theories about man’s arrival on the American continent via the Pacific Ocean, for example. Our analysis, however, will focus on other aspects in relation to this people, more specifically the focus will be on their descendants and the state in which they were when the Europeans arrived here, also covering the relations that developed between whites and Indians from then on.

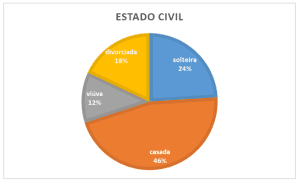

The truth is that we do not know for sure how many Indians existed in the year 1500 in what would become the Brazilian territory today. According to Fausto (2009) the calculations in this regard vary between 2 million for the entire area or about 5 million living in the Amazon alone. According to Narloch (2011) estimates range from 1 million to 3.5 million Indians. Already, according to Koshiba (1994), the numbers range from 189,000 to 1 million natives. Fausto (2009) states that there are currently between 300 and 350,000 Indians in the country, but Narloch (2011) argues that this estimate does not take into account the figure of the “colonial Indian”, that is, the one who left the tribe willingly or by dazzle with European culture, adopted a name Portuguese, married and helped form the famous Brazilian miscegenation, where his descendants , often, they do not recognize themselves as Indians nowadays.

According to Bueno (1997), when Pedro Álvares Cabral arrived in Brazil, at the time of the so-called “discovery”, the Tupinambás and Tupiniquins indians dominated practically the entire coastal coast, having driven the so-called tapuias inland. Koshiba (1994) states that the Brazilian coast at that time was occupied mainly by the Tupi-Guarani Indians, or simply Tupis. They belonged to the same culture and spoke the same language, being grouped into small villages of about three thousand inhabitants, but these villages were always in a state of war with each other. According to Bueno (1997) other indigenous denominations were present in The Brazilian territory, such as: potiguar, tremembé, tabajara, caeté, aimoré, goitacá, tamoio and carijó, among others. But the Tupinambás constituted the Tupi people par excellence, the other Tupi tribes would be their descendants. The Tupinambás lived from the right bank of the São Francisco River to the Recôncavo Baiano.

According to Koshiba (1994), the indigenous peoples who had the first contact with the Portuguese in the 16th century were characterized by egalitarianism within their communities, that is, there were no social classes. Another fundamental characteristic of the Indian was its warrior character, in addition to the existence of a chronic enmity among the various neighboring tribes, which according to Narloch (2011) produced a calendar of wars between them, the Tupi Indians being obsessed by war. Victory in the war and the capture of enemies depended on the status of the warrior within his tribe: he could marry or have more wives, for example. The enemy captured in the war by the Tupinambás, who were cannibals, only had the option of being devoured in a festive ceremony that brought together all the tribe and guests of the neighborhood. This “barbaric custom” – anthropophagy – as Bueno (1997) states, horrified Europeans and was part of a ritual of revenge. The Indian captured on the battlefield belonged to the one who had first touched him, was led triumphantly to the village of the enemy being insulted and mistreated at that first moment; then he was treated well and even received a wife to take care of him, he could walk freely, but he could not escape, in fact, the idea of running away was not even in his head. According to Koshiba (1994), his execution often took years to occur and, when the time came, it was also for him a glorious moment, for he had a death considered worthy, which made sense to the extent that his tribe also did the same rituals with his enemies, in addition to that, he had the opportunity to die as an angry man, warrior, unlike the weak Indian woman who died without similar honors , thus also distinguished the importance given to man in relation to women. After the execution, the whole tribe ate the victim’s flesh and drank his blood, a way to seize the enemy’s strength. “The Indians give death to the warrior for the warrior to remain”, “thus an identity is established between the executioner and the victim, which is essential, because it prevents the act of execution of one warrior by another from becoming a denial of the warrior himself.” (KOSHIBA, 1994, p.23).

Also according to Koshiba (1994) this issue of the “warrior Indian” is fundamental to understand the basis of his culture, because the warrior does not fear death and those who do not fear death cannot be mastered; death will always be preferable to any form of servitude. As for the war itself, it can never come to a final and final decision, for the end of the possibility of new wars eliminates the figure of the warrior, making it socially unnecessary. “In the execution of a warrior, all warriors are defeated, because they are eternal, although therefore war is also eternalized.”

Continuing, Koshiba (1994) states that indigenous societies are opposed by sexual division: on the one hand, the strong-valued warrior-man and, on the other hand, the fragile-devalued-working-woman. Thus, the position of women in indigenous society is subordinated to the position of man. Being a warrior is important, work is an inferior function, aimed at women. It was the woman who practiced agriculture, sowing, conserving and harvesting, the man was only responsible for felling the trees and preparing the land. The woman was dedicated “to the collection of wild fruits, collaborated in fishing, transported hunting products, made flour, cauim, coconut oil, spun cotton, weaved nets and baskets, manufactured ceramic utensils, took care of animals, children, prepared food for meals, etc.” “It was a male task, hunting, fishing, canoeing, housing construction and, mainly, warrior activity.” (KOSHIBA, 1994, p.30-31).

Here it is also up to koshiba (1994), another important observation about indigenous culture with regard to the economy, because we can characterize it much more as a collecting society than a producer, despite the existence of its agriculture as described above, because the collection – hunting, fishing, etc. – overlapped it. A collecting economy does not exclude the production of food, provided that the latter has a secondary or subsidiary role as in the case of the Indians. In relation to the continuous and arduous work as we know it, this did not exist among the Indians, because, according to Koshiba (1994) the abundance of the land provided everything they needed to eat; the Indians were good hunters, good fishermen and great divers and there was not the slightest indication that they passed needs. Thus, according to Koshiba (1994), indigenous society was also characterized as a “free time” society, where no more than three or four hours a day was spent obtaining the necessary food without the need to gather and keep provisions, governing itself by completely different principles of the European way of life. Hence, the often prejudiced view that the Indian was a lazy being.

Another point that deserves to be highlighted in indigenous society and culture concerns the lack of a government recognized as such, without having any individual provided with authority capable of representing them and speaking on their behalf, being the egalitarian society and without private property, therefore, they did not fight for wealth, not needing a state or government; if they had chiefs, they obeyed them of their own free will, not out of obligation. (KOSHIBA, 1994)

Another important aspect of The Indian culture in Brazil narrated by Koshiba (1994) concerns the male-female relationship, because a man had several women and could abandon them for the simplest reasons; if they found them with another man there was no problem either, there was no feeling of fidelity or possession in the relationship, so there was no marriage. “In short, the union between men and women was unstable due to the husbands’ lack of authority over their wives.” In relation to the children too, the Indians did not exercise any form of authority over them, not punishing them, only raised them until each was able to take care of his life alone; not that the Indians did not love their children, on the contrary, they did more good to them than themselves, but the creation according to the Portuguese was extremely vicious and without any concern for virtues. Thus, according to the Portuguese, there was no family order in Brazilian indigenous society.

Narloch (2011), makes an interesting analysis about the portraits that historians made of the Brazilian Indians at various times in our history: at the beginning, at the time of discovery, the natives were described as uncivilized beings, they were like animals that needed to be domesticated; already in the nineteenth century, a current of scholars propagated the image of romantic Indianism portraying the native as the good savage, “owner of an intangible moral”; in the twentieth century part of this vision was maintained, however, adding to the image of the original and pure indigenous culture, the question of its destruction “by the greedy and cruel conquerors”. The story told in this way portrays the Indians as passive beings who had no choice but to fight the Portuguese or submit to them. This discourse passes the image that the Indians of America lived in full harmony between them and with nature, until the Portuguese arrived, fought cruel wars and ended up destroying the environment, people and culture of that people. New studies, which at no time deny the hunts that the Indians suffered, show that they were not only helpless victims in this process, but at many times made their choices and expressed their preferences, because the Portuguese were in much smaller numbers and to remain safe and “friends” of the Indians, were forced to accept these decisions. “Many Indians were friends of the whites, allies in wars, neighbors who mingled until they became the Brazilian population today.” Indians and whites had many parties together, with the right to a lot of drinking showing that that clash of civilization was not only characterized as tragedy and conflict.

Narloch (2011) defends the thesis that when the European encountered the Indian in the sixteenth century, he put an end to an isolation caused by human migrations that was about 50,000 years old. So much time of separation caused a culture shock and epidemics that affected both sides: that reunion was one of the most extraordinary events in human history, with remarkable advantages and discoveries for both Europeans and indigenous nations that lived here.

In conclusion, Narloch (2011) also reports that, until the arrival of the European in Brazil, in terms of historical evolution as we know it today, the Indians had not “reached the Iron Age and not even that of bronze”, they did not know either the wheel and its agriculture was non-intensive and rudimentary, of low productivity, making it depending on luck or misfortune in hunting or collecting , they went through periods of hunger. The isolation of the Native American for so long left him on the margins of the cultural integration that marked the history of Europeans, Africans and Asians since antiquity, because, through trade, conquests and wars, new technologies and customs have passed from one culture to another.

3. THE PORTUGUESE COLONIZERS

According to Fausto (2009, p.9-11), the arrival of the Portuguese in Brazil was “one of the episodes of portuguese maritime expansion that began in the early 15th century”. Almost a hundred years before Christopher Columbus, who was sent by the Spaniards, arrived in America, Portugal was already making its first steps towards its expansion. This fact was due to several factors, among them: the experience in long-distance trade accumulated during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries with the partnership developed with the Genoese that transformed Lisbon into a major center of international trade; Portugal’s economic involvement with the Islamic world with the use of currency as a means of payment; the geographical position of the country near the Atlantic islands and the coast of Africa; the favorable political conditions with the early unification of the kingdom in relation to other nations such as France, Spain, England and Italy, involved in internal and external conflicts; the interests of the various Portuguese classes and social groups – merchants, king, nobility, clergy and people – in the search for new economic perspectives and better living conditions; the invention and improvement of various navigation and location instruments such as the astrolabe and quadrant, in addition to the development of naval architecture with the construction of the caravel that was a lighter, faster and smaller silent vessel that allowed a better approach to the mainland. Given all these factors, the expansion became a great national project Portuguese, in which all or almost all were involved and that crossed several centuries.

Also, according to Fausto (2009) the search for gold and spices became the great goals of portuguese expansion. Gold, mainly, because it is used as a reliable currency and spices for use in food conservation and for satisfying eating habits. So basically, what led men to venture out to sea, traveling for many days, feeding precariously and often risking their own lives was the pursuit of riches.

Fausto (2009) reports that the conquest of Ceuta, located in North Africa, in 1415 was the initial milestone of portugal’s maritime expansion, which later evolved into the exploration of the West African coast and the islands of the Atlantic Ocean. From the passage of Cape Bojador in 1434 by Gil Eanes to the overtaking of the Cape of Good Hope in 1487 by Bartolomeu Dias was 53 years. This milestone would allow penetration into the Indian Ocean that would take the Portuguese to the Indies and then to China and Japan.

In this trajectory of expanding Portuguese horizons by sea, according to Fausto (2009), in March of 1500 the largest fleet of caravels destined to the Indies departed from Lisbon; there were 13 ships under the command of nobleman Pedro Alvares Cabral. The fleet passed through the Cape Verde Islands, taking a westward course, moving away from the African coast until reaching what would be the Brazilian lands on April 21 of that year. At this point there is great discussion regarding the arrival of the Portuguese in Brazil, whether it would have been occasional or intentional, however, it is not the objective of this work to deepen this debate.

After the discovery of these new lands, it was necessary to occupy and exploit them, because, according to Asunción (2003) colonization was a viable proposal since the Portuguese domains could provide identical riches – gold and silver – those of the Spanish colonies of America. But in the first thirty-five years, according to Fausto (2009) the main economic activity in Brazilian lands was the extraction of brazilwood that was obtained through exchanges with the Indians. The Indian entered with the manpower to fell trees and received in return pieces of fabrics, knives, knives, axes, hook for fishing and other trinkets. At this point, Narloch (2011) makes an important observation about this system of exchanges between Portuguese and Indians, because these so-called trinkets were actually “riches and customs selected during millennia of contact between civilizations of Europe, Asia and Africa”, and adds stating that for the Indians it was a great deal to have access to these objects through the exchange with parrots and brazilwood , therefore, these exchanges ended up inserting the Indians into the “Iron Age”.

According to Asunción (2003) aiming to productively occupy the territory and colonize it without major investments by the crown, Brazil was divided into large swathes of land that were distributed to some members of the Portuguese nobility, the so-called hereditary captaincies, effectively initiating the settlement of the territory constantly threatened with invasion and possession by the French. Such landowners – donatries – should use their own resources in the exploitation of their possessions. However, the great distance between colony and metropolis, the attacks of the Indians on the properties, the lack of training of the crown employees, the isolation of the captaincies from each other and, mainly, the lack of own resources of the donors for investment, were responsible for the failure of this model of colonization, and only two captaincies were somewhat successful: Recife and São Vicente.

This failure led to the creation of the figure of the general government aiming at the centralization of the administration and greater control of the colony by the metropolis. According to Fausto (2009), together with the first governor-general – Tomé de Souza – who arrived in Brazil in 1549 came the first Jesuits – Manoel da Nóbrega and five companions – with the aim of catechizing the Indians and disciplining the clergy drain of bad fame existing in the colony. It was given the beginning of the organization of the State and the Church in the country in a closely linked way. In this same line of reasoning, Asunción (2003, p.10) states that the colonization project was not only for land occupation, but for the legitimation of this possession, that is, colonizing meant also Christianizing, thus, the Jesuits were vital elements in the colonization process.

Given all that has been exposed so far, at this point in history there is the beginning of the relationship between the three main human elements that will be analyzed in this work: the Jesuits, the colonizers and the Indians. And, the main question raised concerns the extent to which the Jesuits, with their evangelizing action, together with the action of the colonizer Portuguese in search of riches, would have been responsible for the tragedy of the Indian in our country. To answer this question, in the next chapter, these relations will be analyzed, that is, the colonizing-Indian, colonizing-Jesuit-Jesuit and Jesuit-Indian relations.

4. THE RELATIONS BETWEEN THE INDIAN, THE JESUIT AND THE COLONIZER

After the so-called discovery of Brazil, Koshiba (1994) reports that the first contacts between Portuguese and indigenous people must have been peaceful, because these Indians were friendly and deeply attracted by the objects offered by the Portuguese as gifts. Even then, with the fixation on the land of the first villagers, there was still a certain desire for understanding, but the divergences began to appear and, initially, the consequences of these frictions were extremely catastrophic for the Portuguese who had almost all of the flagships made unfeasible by attacks by the Indians. An example of this type of occurrence was the alliance established between the Potiguaras Indians with French pirates who joined and antagonized the inhabitants of the capitals of Itamaracá and Pernambuco, burning mills and killing Portuguese. The indigenous attacked and made impossible all the investments contributed in the country until that time. According to Narloch (2011), at first, navigators arrived in places still unknown and were often attacked immediately. Even with their swords and arcabuzes, the ammunition was restricted and the loading of their weapons was somewhat time-consuming, facilitating the attacks of the Indians.

According to Koshiba (1994), the cause of the beginning of these conflicts was the behavior of the Portuguese, always ambitious, who proposed interesting deals for the Indians in terms of remuneration for the cutting of the brazilwood, using the paraphernalia they had, but gradually the demands on the Indians were increasing until they reached the breaking point. Basically, the Portuguese arrived in the country and “appropriated the indigenous lands, took their women, demanded work and considered themselves their natural masters”. They thought they were superior and “believed that the new land belonged to them by right.” Where it was not possible to exercise this right peacefully, they did not hesitate to use force and violence.

Koshiba (1994) states that the colonizers used against the Indians the “strategy of fear” with the use of violence, in the so-called “natural war”; the fear of death would lead the human being, in this case the Indian, to exchange his freedom for submission, making servitude something preferable to death. Culturally, the Indians saw war as a fight against fear, because their wars were fought, as was already exposed in this work, within a code of ethics where even the execution of the enemy valued their attitude of courage and bravery within a sacred ritual, the very way they treated their prisoners was not intended for degradation or humiliation. With the Portuguese, the indigenous warrior was hanged and his inert body was exposed humiliatingly in order to create and impose terror in order to produce domination. The way the Portuguese fought had a devastating psychological effect on the Indians.

During the period of the implementation of the captaincies, Koshiba (1994) listed three basic models of Portuguese occupation with regard to the relationship between the Indian and the white man: in Pernambuco, there was military conflict and simply the indigenous peoples were defeated and expelled from the region; in Bahia, a distinction was made between friendly Indians and enemy Indians, establishing alliances with the Allied Indians, who assisted in the defense against the hostile Indians, in addition to providing supplies and labor; in São Vicente there was a widespread cross between the races, with the emergence of the Mamluk mestizo causing the Portuguese in this region to incorporate much of the indigenous material culture. The other captaincies fell in the face of fierce attacks from the Indians.

With the implementation of the general government in 1549, Tomé de Souza brought with him the so-called “Regiment” elaborated in 1548, which, according to Koshiba (1994) gathered a series of measures to be taken in relation to the hostile Indians. The central point of this project was the issue of “subjection and vassalation” where the Indian would be treated as a source of labor, supplier of supplies, in addition to serving as a soldier in defense against enemy tribes. Violent actions were restricted to hostile Indians, against whom the “just war” was authorized where the defeated Indians would be enslaved.

Also according to Koshiba (1994), in the mandate of the second governor general, Duarte da Costa (1553-1558), the precarious balance achieved in Bahia, in relations with the Indians was broken by the issue of land dispute. The Indians invaded several properties of the Portuguese trying to regain ownership of the land. The government’s reaction was immediate and violent, invading several villages, setting them on fire and killing many Indians. The clashes continued, but in the end, in the face of violent repression, the remaining Indians were subjected.

The third governor general, Mem de Sá (1558-1572), according to Koshiba (1994), waged offensive war against the tribes of the Recôncavo, sending a great expedition to break a powerful resistance of the Tapuia Indians of Paraguaçu. Thus, from the government of Mem de Sá began a new phase of conquests that lasted until 1599 with the pacification of the potiguaras by Jerônimo de Albuquerque. From Bahia there was an incursion in Espírito Santo at the request of the owner Vasco Fernandes Coutinho who was bothered by the Aimorés Indians. In 1560, Mem de Sá faced in Rio de Janeiro, the French allied to the Tamoios Indians.

At that time, the French invasion of Rio de Janeiro, a remarkable episode in the region of Ubatuba, had the participation of Father Anchieta and Father Manoel da Nóbrega, and concerns the negotiation of a truce between Portuguese and Tamoios Indians in 1563, which, if not signed, could end the Portuguese colonizing trajectory in our country, because the indigenous forces totaled about 5,000 men and still received the support of the French. The Portuguese fought with the help of the Temimino Indians and Tupiniquins against the French and, after expelling them from Rio de Janeiro, they (Portuguese) fortified themselves and broke the truce unilaterally, defeating the Tamoios in battle, killing them and enslaving those who survived. The story goes, according to Bueno (1997, p.35), that the two priests did nothing to prevent the massacre of the Indians by the Portuguese, despite being considered their protectors. The religious’s justification for this omitted attitude was that they were hostile Indians, who were not subject to acculturation and Christianization and, in this case, the principle of just war would apply.

In the government of Luís de Brito de Almeida (1573-1578), Koshiba (1994) reports that the problems with the Indians were concentrated in the north of the country, in this case, with the fillies of the Paraíba River. From the government of Manuel Teles Barreto (1583-1587) the Portuguese and Spanish offensives began, due to the Union of Iberian Crowns at that time. After many struggles, deaths and twists only in 1599, as stated earlier, Jerome de Albuquerque established the definitive peace with the potiguaras.

From 1599, according to Koshiba (1994) the Portuguese controlled the coastal strip that went from São Vicente to Rio Grande do Norte, with the Indians placed totally on the defensive. At that time, there was no indigenous group in the country capable of endangering Portuguese colonization.

In this struggle, between white and Indians, what draws attention is how a minority – whites – managed to submit a large majority – Indians. This was because in the face of a common enemy the various indigenous groups did not unite, on the contrary, they took advantage of making alliances with the Europeans to defeat tribes considered enemies. The greatest example of the participation of Indians in the extermination of Indians, according to Narloch (2011) was in the so-called Tamoios War, between 1556 and 1557, where the Tupiniquins and the Temiminoos joined the Portuguese to expel the French from Rio de Janeiro, but at the same time fight their enemies: the Tupinambás, also called tamoios.

Koshiba (1994) states that the Portuguese used various tricks to foment discord among Indians even from the same tribe, inviting them to parties and offering them alcoholic beverages to intoxicate them. Soon after, the Portuguese provoked these drunken Indians who began to accuse each other by handing over the culprits for some unwanted act they had done. The punishment was exemplary, with the condemned placed in the mouths of cannons that were fired; others were handed over to rival tribes to be devoured, further increasing enmity between them.

In addition to the wars fought in the 16th century between whites and Indians, another reason for great mortality among the natives was the contagion caused by diseases brought by Europeans, especially influenza, smallpox and measles. This “simple contagion created epidemics that devastated entire indigenous nations.” (NARLOCH, 2011, p.59). On this point, Fausto (2009) adds that there was a real “demographic catastrophe”, because the Indians had no biological defense for these diseases, and two epidemic waves stood out for their virulence between the years 1562 and 1563, killing more than 60,000 Indians.

Finally, Fausto (2009) emphasizes the resistance of the Indian to the various forms of subjection imposed by the white man, either by war, by escape or by the simple refusal to compulsory work. The Indian had better conditions to resist that African slaves, because they knew the Brazilian territory better, were in their home.

According to Fausto (2009), from the 1570s, the Portuguese crown began to draft laws to try to prevent the death and widespread slavery of Indians, but the laws implemented contained caveats and were constantly circumvented, as in the case of “just wars” or defensive wars, or in the case of punishment for the practice of anthropophagy, or even in the case of rescue , which consisted of the purchase of Indian prisoners from other tribes who were to be devoured and destined for slavery. Only in 1758 did the crown determine the definitive liberation of indigenous slaves.

The Jesuits were sent to Brazil, in a joint strategy of Portugal and Rome to promote evangelization and defend and spread the Catholic faith somewhat shaken by the Protestant Reformation. Asunción (2003) reports that, together with the strategy of settlement and colonization, the main objective of the Portuguese crown was to safeguard the lands discovered before they were attacked by other nations. These actions, as stated earlier, aimed to legitimize the ownership of land by Portugal. “The main objective of the Society of Jesus” in Brazil “was to convert indigenous peoples to the Catholic faith.” (ASSUNÇÃO, 2003, p.11).

According to Strieder (2009) the first activity that characterized Jesuit work in Brazil was instruction, having founded its first college in Bahia only one year after its arrival in the colony. This activity grew so much that, in 1749, it reached the impressive mark of 669 colleges, 176 seminars, 61 houses of studies of the Order and 24 universities. These schools were free and followed the “Ratio Studiorum” as a pedagogical system. The second activity characteristic of the Jesuits was the missions, where the missionaries received special training on how to adapt to different cultures, in addition to learning their respective languages. This missionary method was very successful, but it was not always well regarded by the other ecclesiastical authorities. For the indigenous, the fact that the Jesuits spoke their language distinguished them from the slave colonizer. The missionaries also used rites, names, references and myths proper to the Indians to achieve their goals.

Strieder (2009) says that the Jesuits soon realized the totally corrupt character of the covetously driven colonizers and depraved in their customs. Thus, in order to achieve their goals, they realized that they needed to be close to political power. Thus, the villages and colleges received government land to produce and maintain; the missions received subsidies and it was made that the slavery of the indigenous was prohibited by laws lowered by kings. As for the introduction of black slaves as a labor force in their properties and in the colonial system as a whole, at first the Jesuits were reticent, but then accepted it by not contesting it properly.

In this same line of reasoning, Koshiba (1994) lists the two main problems that hindered the Jesuit project in Brazil: on the one hand, the greed of the villagers that led them to indiscipline and disobedience to authority; and on the other hand the ignorance of authority by the Indians that together with egalitarianism and lack of greed made authority without justification. The absence of authority for the Jesuits freed the human being into the practice of two vices: greed and sensuality. The villagers got lost in both and the Indians in the second.

According to Koshiba (1994) the Indian’s indifference to the accumulation of wealth did not lead him to disciplined work or to the creation of a foresighted spirit, thus, the egalitarianism of the Indians was seen as a problem by the Jesuits and this would result in their moral relaxation that would lead to sensuality. The lack of authority of the Indian man “made conjugal relations loose and unstable” not favoring the formation and constitution of families where children could have a moral reference to their formation. Thus, the Indians came to be seen as vicious beings, as opposed to the innocence with which they were characterized at the time of discovery; not to mention the customs of anthropophagy, polygamy and unmotivated warfare that were indigenous customs considered as real catastrophes for the Jesuits.

Fausto (2009, p.23) states that the Jesuits “had no respect for indigenous culture, on the contrary, for them it was doubtful that the Indians were people” and quotes Father Manuel da Nóbrega as saying that “Indians are dogs in eating and killing each other, and they are pigs in vices and the way they treat themselves”. Perhaps, for this reason, Nóbrega preached, according to Koshiba (1994), the subjection of the Indian as a way of making him obedient through coercion and fear, however, the Jesuits knew how to give better than the colonizer, the question of rigor and gentleness in their “technique of domination” in relation to the Indians. For Nóbrega, once the subjection was obtained with the indigenous peoples relocated to a new social base, the ground would be prepared for them to receive the faith. (KOSHIBA, 1994). The subjection meant bringing the Indians into the conviviality with the Christians, however, the Christianized Indians were subjected to slave labor by the villagers, who also abused their women contrary to the content of the word of God that they tried so hard to transmit to the indians. (KOSHIBA, 1994). Therefore, the Jesuits began to defend the settlement to separate the already Christianized Indians from the colonizers, considered “bad Christians” by the Jesuits.

Fausto (2009) reports that the arrival of the Portuguese and, especially, religious to Brazil, was associated by the indigenous peoples with the arrival of the “great shamans”, who, according to their beliefs, walked the world, “from village to village, healing, prophesying and speaking of a land of abundance”. Thus, the work of domination undertaken by the religious with the Indians was facilitated by the very condition of acceptance of their beliefs. The religious were gaining the trust of the indigenous also, to the extent that they defended them from the exploitation and slavery undertaken by the colonizers. According to Koshiba (1994), the Jesuits did not see the Indian only as an instrument of work as did the colonizer, so this divergence between religious and conquerors always placed them in a position of conflict. Fausto (2009, p.23) talks about this subject, stating that “religious orders had the merit of trying to protect the Indians from slavery imposed by the settlers, the resulting in numerous frictions between settlers and priests”.

Returning to the facts, Asunción (2003, p.11) reports that the first Jesuits who came to the expedition of Tomé de Souza in 1549 were: Father Manuel da Nóbrega (superior priest), Antônio Pires, Leonardo Nunes, Juan de Azpilcueta Navarro and brothers Vicente Rodrigues and Diogo Jácome. Its main objective, as previously said, was the conversion of the “Gentiles” and, for this to happen “it was necessary for the missionaries to live with the indigenous, in order to catechize them, to take care of their diseases, to teach new artisanal and agricultural techniques. Thus, the villages and missions were emerging.”

Asunción (2001) defines village as a small village of Indians; village, as a village run by missionaries or a civil authority and; finally, mission or reduction as an institution formed by missionaries with the objective of spreading the Catholic faith through catechesis directed to indigenous peoples, in addition to orientation to agricultural and pastoral work, based on the collective ownership of the means of production and free and family work, ensuring the support of the community and selling the surplus in the market.

According to Koshiba (1994), in the villages and in the missions or reductions, the lives of the Indians were completely remodeled based on a close connection of work and religious life, following a strict routine that began early in the morning with religious instruction for women, then work in the making of clothes and fabrics for them. Then the children came to learn to read and write and receive the lessons of the doctrine; at the end of the classes, the boys would help with hunting and fishing. The adult men went straight to the field, from where they returned only at night, when they then received the lessons of doctrine. The Indians were divided into houses that separated them into “families” rather than collective dwellings, and instead of life rhythmically by nature, they began to submit to chronological time like europeans. Its conversion was accompanied by the pedagogical imposition of Portuguese culture, not characterizing in any way an innocent practice, since it stifled its own cultural manifestations. Their tribal sexual practices were suppressed, being replaced by rules that favored work and prayer. The habit of covering the body with clothes was introduced. Finally, the regional variations of the language were unified by the “general language” introduced by the Jesuits.

Bueno (1997) narrates that between 1557 and 1561, in a first missionary action in Brazil, the Jesuits gathered about 34,000 Indians in 11 villages near Salvador, but when Governor General Mem de Sá decreed a fair war on the Caeté Indians, the settlers took the opportunity to attack the villages and enslave about 19,000 Indians, the other 15,000 Indians were killed by a smallpox epidemic. With this disastrous experience, this type of enterprise practically disappeared from Brazilian lands at that time, being repeated, however, years later in Paraná, Mato Grosso, Rio Grande do Sul, Paraguay and northern Argentina.

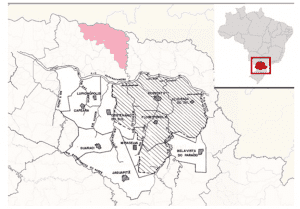

The Missions, according to Bueno (1997), were about 60 villages located in the Guairá (between the Paranapanema and Iguaçu rivers), the Itatim (on the left bank of the Paraguay River), the Tape (west of Rio Grande do Sul) and between the Uruguay and Paraná rivers (Rio Grande do Sul and Argentina), some with more than 5,000 inhabitants. These communities were attacked and decimated during the period from 1628 to 1641 by the bandeirantes of São Paulo in the hunt for the Indian in search of labor for slavery; but they were reborn, and during 11 decades of peace they grew and prospered; around the year 1700 formed the 30 peoples with more than 150,000 inhabitants. It is worth mentioning the victory of the Guarani Indians in a battle against a flag in 1641 in northern Argentina when they had the support of the Jesuit priests and decimated about 200 Paulistas, marking the last confrontation between them.

On the flags that became great enemies of missionary reductions, Fausto (2009) states that they were the great mark left by São Paulo in the colonial life of the seventeenth century, where expeditions of thousands of Indians, Mamluks and whites – these in smaller numbers – launched themselves through the hinterland in the hunt for other Indians to be enslaved and in the search for precious metals. Notes from the Jesuits estimated 300,000 Indians captured only in paraguayan missions that they would be sold as slaves in São Vicente and Rio de Janeiro. Fausto himself considers this number exaggerated, but points out that other statistics also presented always high amounts. Narloch (2011) also disputes the numbers raised by the Jesuits, arguing that the image of the barbarism of the Paulistas, narrated by them, helped to hide the real reason for the emptying of missions, because many Indians, in fact, fled out of lack of confidence in the priests themselves or to seek a new life without the routine and rigor of Christian norms. These exaggerated statistics of the Jesuits were sent in communiqués to the European authorities in the hope of obtaining support against the attacks of the Paulistas.

In relation to the Paraguayan Missions called the “Republic of the Reduced Indians”, Strieder (2009) adds that of the 30 peoples, 7 were located in regions now belonging to Brazil. About its history, this author adds that, since the beginning of the colonization process in the sixteenth century, the Jesuits had already realized that the colonizers had come to America with the sole intention of enriching and for this they needed the slave labor of the Indian. Through the system of “encomiendas” 100,000 Indians were distributed in 320 Spanish latifúndios. Only a few religious and civil servants, besides the Jesuits, opposed the massacre and enslavement of the indigenous peoples. From 1609, the missionaries were authorized to put into practice their system of reductions away from the Spanish colonizers. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were founded about 70 indian settlements with approximately 200,000 inhabitants, located from the Prata River Basin to the tributaries of the Amazon River. Paraguayan reductions lasted 158 years, that is, until 1767. In relation to the power in the reductions, the same was exercised by the higher Jesuit together with the indigenous leaders – the chieftains. Thus, there was the meeting of two cultures that were in different stages of development, however, it is worth mentioning that the European cultural aspects were predominant. But the fundamental interest of the Jesuits, in this case, was the conversion of the Indian to Christianity and the civilizing effort was only a means to achieve their goals.

According to Bueno (1997) the missionary project raises many unanswered questions: Would it have been a communist project? Was its implementation based on Thomas Morus’ “Utopia” or Plato’s “Republic”, or “City of the Sun” by Campanella? To what extent would the work of the priests have been humanitarian? Wouldn’t this project have been the shortest path to the Guarani genocide?

Bueno (1997) reports that the main factor for the destruction of this missionary project was the issue of its location being between two expanding empires – Portugal and Spain. And, through the Treaty of Madrid signed between these two countries in 1750, the borders between their colonies were defined, and the Missions corresponded to practically a “buffer state” between them. After the signing of this agreement, priests and Indians received an ultimatum to leave the region, as they did not comply with the order, the so-called “Guaranitic wars” were triggered. In 1756 a coalition of Portuguese and Spanish military forces massacred the poorly armed indigenous forces putting an end to the project.

In the case of Portuguese colonization, Fausto (2009) reports that the Catholic Church and the State worked together in the organization of the administration of Brazil, but the Church was subordinated to the State by the mechanism of the so-called “royal patronage”, in which, basically, the tithing collected from the faithful went to the crown coffers that in return remunerated the clergy and was responsible for the construction and maintenance of the temples. But the Jesuits, to the extent that they became great entrepreneurs, not so much depending on the crown’s funds, put into practice their own policies, especially in the defense of the Indian, always clashing with the interests of the colonizers.

By their alliance with the Portuguese crown, according to Asunción (2003), the real favors to the Jesuits were many and transformed them into lords of ingenuity and cattle ranchers, among other commercial activities. The surplus produced on their farms was sold on the market and the profit reinvested in the maintenance and expansion of the properties. As previously discussed, the Jesuits were indigenous defenders against settlers on the issue of slavery, so religious would use African slave labor in their enterprises (other religious orders also did this). The black slave on Jesuit property was not free from violence, for bland lashes and prisons were practices considered acceptable; more violent punishments were already condemned. In the Brazilian colonial period, few Jesuits took a stand against this issue of the horrors of black slavery.

Finally, Narloch (2011) in his book “Politically Incorrect Guide to the History of Brazil” raises some questions for reflection when he states that “the indians killed the most” due to the great rivalry between the tribes and the calendar of wars between them – the tribes signed alliances with the European white man to obtain technological advantages in the war against their ancient enemies. The tribes also went through an emptying, not only because of attacks and diseases, but also by the integration of the Indian by his free will to the way of life of the white man, emerging the figure of the so-called “colonial Indian”. (NARLOCH, 2011). “When the Jesuits implemented intensive agriculture near the villages, obtaining food was no longer a nuisance” for the indigenous who had previously had to devote themselves to harsh daily hunts to obtain food. (NARLOCH, 2011, p.52). The emptying of the missions was not due only to the savagery of the attacks of the Paulistas (bandeirantes), most indians abandoned the Jesuits because of the lack of trust in the priests and the refusal to obey the rigor of Christian norms (NARLOCH, 2011). Epidemics caused by the contact of ethnicgroups were common in the history of mankind not only occurring with Native Americans, many deaths must have occurred also in Europe due to diseases taken from here to there, such as syphilis for example. (NARLOCH, 2011). Finally, the white man is accused of having spread the use of alcoholic beverages among the Indians with all the ills that this addiction has always caused, however, until the time of the discovery of America there was no use of cigarettes or the habit of smoking in Europe, and this addiction was taken from here to there, because the American Indians smoked , smelled and chewed the tobacco leaf and, with contact, the powers and pleasures of smoking also conquered whites with all the evils that this addiction is also capable of causing. (NARLOCH, 2011).

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Everything that was narrated in this work serves to show the controversies existing among several authors in what involves the Indian-Jesuit-colonizer relationship. Some claim that the Jesuits are the great culprits for the destruction of indigenous culture and, consequently, of the Indian in Brazil. However, given what was exposed, it is clear that the conqueror or the colonizer contributed much more effectively to this extermination, to the extent that he fought several wars against the Indians, killing them and enslaving them in large numbers, aiming to dominate and conquer the new lands discovered. The diseases brought from Europe, which the Indians had no biological resistance, were also devastating.

On the other hand, the Society of Jesus came to Brazil, motivated by the conquest of souls for the Catholic Church, threatened by the Protestant Reformation that took place in Europe; he was not concerned with respecting indigenous culture, but rather about implementing the principles of European culture seen as superior at the time. It was also allied to the interests of the Portuguese crown, although, over time it distanced itself from its determinations, so much so that there was the rupture in 1759 with the expulsion of the Jesuits from the kingdom Portuguese.

However, the missionary project itself is very controversial, even today since it interferes and often violently interferes with the culture considered “more fragile” in terms of argumentation, in this case indigenous. However, even today, this method of religious conversion is still widely used and hyped within the Churches, and virtually all religions have their missionaries who are sent to all parts of the world in search of more faithful to their beliefs.

The contact and interaction between peoples by the so-called globalization, which really began with the great navigations, have always brought and still bring marked consequences for the peoples involved. Some societies were virtually destroyed, others survived, but with major cultural transformations, some considered harmful and others as beneficial.

The case of the Brazilian Indian is unfortunately a bad example of the contact between cultures at different stages of development, as can be seen by its own current condition, because the Indian who defines himself as such has actually been reduced by about 20 times in its quantity since he had the contact initiated with the white man.