ORIGINAL ARTICLE

KIRGIZBAEV, Nodirjon [1]

KIRGIZBAEV, Nodirjon. Colonial impact in transforming Hausa gender relations. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 06, Ed. 11, Vol. 01, pp. 123-136. November 2021. ISSN:2448-0959, Access link in: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/history/colonial-impact

SUMMARY

This study aims to discuss how traditionally balanced and well-structured gender relations in West Africa were altered by French and British colonial policies. The main question is whether these policies that presumably were intended to elevate the women’s role in society did in fact diminish them. The problem in this approach was the projection and use of Eurocentric paradigms in culturally and socioeconomically distinct local environments. Methodology consists of empirical research and retrospective study. Utilizing a number of scholarly articles and publications by leading historians it is argued that the colonial rule led to the widening of the inequality gap between the Hausa men and women and caused the further alienation and seclusion of women from social life and limited their opportunities to pursue education and access to decent employment.

Keywords: Hausa gender relations, colonialism, women in Islam, masculine ideology, feminism in Africa.

INTRODUCTION

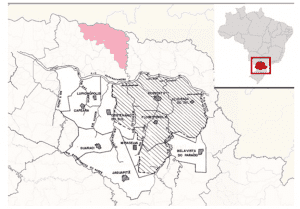

The partition of the African continent into separate countries was an artificial process of colonialism forcing many ethno-linguistic groups to divide and reside over the opposite sides of newly defined national boundaries. One of such large groups was the Sahelian people identified commonly as Hausa. The majority of Hausa live predominantly in northern Nigeria and southern Niger, but some of their communities are scattered throughout other African nations such as Cameroon, Ghana, Chad, and Sudan (MILES, 1994, p. 47).

Aside from dispersing the people of one ethnolinguistic group into living under the authority of distinct political entities, colonial powers also had a profound impact on their social, economic, and cultural heritage, especially concerning gender-related changes in terms of power, status, and property ownership. Policies implemented by French and British colonial authorities in Niger and Nigeria respectively undermined and altered how power relations between men and women were being structured gradually over the past few centuries.

This study aims is to analyze the impact of the colonial rule in widening the inequality gap between the Hausa men and women that may have caused the further alienation and seclusion of women from social life and limited their opportunities to pursue education and access to decent employment. Another important aspect throughout the discussion will involve the role of religion and Islam in particular, and how it intertwined with and affected the colonial approaches in governing the local societies.

Sources used for this paper include academic works and articles discussing various aspects of the social, cultural, and political life of Hausa society in southern Niger and northern Nigeria. The primary objective in selecting the used bibliography is the relevance and reliance of the information provided by the scholars, who have extensive experience and are the recognized leaders in the study of African social history.

DEVELOPMENT

For a better understanding of the following discussion, especially concerning such sensitive issues as ethnicity and gender, it seems important to provide some background on the historical developments, facts, and figures. As it was mentioned in the opening passage, Hausa people reside predominantly in northern Nigeria and southern Niger. During the colonial period from 1890 to 1960, these countries were known as the Colony and Protectorate of Nigeria under British rule, and the Colonie du Niger, which was part of Afrique Occidentale Francaise or French West Africa (MILES, 1994, p. 3).

Hausa people constitute one of the largest and influential ethnic groups in Africa and according to Encyclopedia Britannica (2021), their language is the lingua franca of West Africa that is spoken by at least fifty million people. The CIA World Factbook (2021), on the other hand, claims that in Nigeria alone, the Hausa ethnic group represents 30% of the population that equals over 65 million people and that over 12 million ethnic Hausa reside in Niger. Other countries with substantial Hausa populations are Benin, Ivory Coast, Cameroon, Chad, Sudan, and others (WORLD ATLAS, 2001). But regardless of the disparities in numbers, Hausa people were able to withstand all the challenges brought by the Westerners, and as Coles and Mack (1991, p. 4) righteously note “Hausa culture has maintained its own language and cultural attributes, assimilating the new and useful, and defusing whatever threatened its cohesiveness.”

Such variation in numbers can be traced to different approaches that scholars pursue in studying the Hausa identity. William Miles (1994, p. 43) distinguishes these scholarly approaches into two camps, for one of which ‘Hausa’ is primarily a linguistic designation, while the other stresses the importance of ethnic denominators. The former group points out the substantial historical and religious diversity among the various Hausa-speaking people and asserts their commonality is bound only by language. The latter group argues this definition by stating that not all Hausa speakers are Hausa, hence ethnicity is the major factor.

The issue of Hausa identity is further complicated by the local narrative about the importance of geographical origin, and religious affiliation. According to traditional Hausa folklore and cosmogony, Hausa people are the ones who can relate themselves to one of the seven nations or ‘families’ of Daurawa, Kanawa, Gobirawa, Ranawa, Zazzawa, Katsinawa, and Biramawa, all set up by the descendants of Queen Daura and Persian prince Abu Yazidu (Bayajidda) (MILES, 1994, p. 45). Another question is the religious association: since Islam is the dominant religion in Hausa society, are others not fit to be Hausa under this categorization? (MILES, 1994, p. 47).

For practical reasons and considering the geographical scope of this study to be concerned with Hausa people of northern Nigeria and southern Niger, hereafter Hausa will be regarded as a single ethnolinguistic group. With the concern of one of the discussion questions being related to the role of Islam in shaping the colonial policies, the focus will also be directed toward Islam, but which will not exclude the indigenous or other religious practices out of the context.

The strategy of assimilation and colonial exploitation was carried out by the imperial powers in two different ways. Hausa of Niger came under direct French rule, which displayed little tolerance, admiration, or respect for indigenous institutions or leaders. Undermining local customary law and traditions, they imposed French procedures and norms. Britain, on the other hand, preferred indirect rule, molding and adapting local institutions gradually, cautiously promoting British values and goals without discrediting indigenous culture (MILES, 1994, p. 10).

Some scholars, such as Barbara Cooper (1998, p. 31) argue, that despite the different approaches both colonial authorities attempted “to rule their territories as cheaply as possible while reaping the maximum revenue from them.” She further contemplates that by ‘assimilation’ the French were, in reality, practicing the same approach as the British in administering their territory.

Regardless of the motives and approaches, it can be noted that colonial authorities were not concerned with elevating the living standards of the local population. Their indifference and the lack of action can also be stipulated as a negative factor in the promulgated Eurocentric masculine ideology, class, and gender division. Hausa society being patriarchal thus absorbed the European perspective leading to further suppression of women’s rights. To put in other words, women’s marginality was the cause of “a sociocultural and political condition of institutional exclusion resulting from the conjuncture of patriarchy, colonialism, and hegemonic class ideologies” (ALIDOU, 2011, p. 43).

Author Helen Callaway (1987, p. 52) underlines that under ‘indirect rule’ European officers dealt only with African male chiefs and bureaucratic officials, assuming that African women were dependent and subordinate to men even in areas where women were noted for their independence such as trading and activities in local socio-political organizations. According to her:

On the whole, colonial officers projected the gender representations of their own society on their perception of African gender relations and, of far greater significance, on their shaping of the new social, economic, and political order which colonialism gradually brought about (CALLAWAY, 1987, p. 52).

European male-centered attitude further transcended into colonial economic policies devised for modernization and development of the agricultural sector.

ECONOMIC DISADVANTAGE

With the introduction of cash crops which became one of the primary export commodities, extension services and training were offered to men, but not to women who were actively involved in the family farm work (CALLAWAY, 1987, p. 53). Contrary to this, some authors argue that women in rural Hausaland, unlike those elsewhere in Africa, are not encouraged to participate directly in farm operations (CALLAWAY, 1984, p. 441). Others based on their observations conclude that “the overall status and wealth of Hausa women is a function of the economic standing of their husbands” (MILES, 1994, p. 218). Can it then be presumed that early European colonizers also shared such a vision or did the absence of a female labor force in agriculture occur as a result of colonial policies? One dimension is quite obvious: the indifference and exclusion of women by the colonial administrations from training and education further alienated women and widened the gender gap.

Hausa women, on the other hand, do not limit their status and wealth to the economic standing of their male relatives. For them, it is “arziki” which is not just wealth and prosperity, but also a philosophical and spiritual quality that brings good fortune (MILES, 1994, p. 218). This phenomenon is extended to even greater meaning when Nigerien Hausa refers to their Nigerian kin as having more arziki.

Another explanation for the lack of interest or choice for women in farming is the characteristic of “kulle” or seclusion, which has moderate and extreme manifestations. In extreme instances, women are completely secluded within the domestic space. In moderate kulle women are allowed greater mobility but often with the permission of the male head of the household (ALIDOU, 2011, p. 44).

Some women choose to be secluded, even if it is not economically practical just to show their aspiration of belonging to the elite merchant class (COOPER, 1998, p. 33). Some regard kulle as a restriction and protection from the outside world, with no obligations to fetch water and wood, and opportunity to engage in crafts and petty trade, proceeds from which are the personal property of women and do not have to be shared (MACK, 1991, p. 110).

With seclusion being a traditional custom associated with religion, how does it correspond to colonial policies? Until the early twentieth century, kulle was practiced only by wives of the religious teachers known as mallams, but with the abolition of slavery, it spread to other social classes. As women slaves were freed they chose to seclude themselves, and newly freed men kept their wives in kulle to show their status (CALLAWAY, 1987, p. 59).

Ironically, former slaves and other materially less privileged Hausa did not enjoy the seclusion for very long. With the introduction of the cash crop economy, taxation, and the cultural bias about the necessity of living it up to Western standards, it became increasingly difficult to support the family.

So women and daughters in urban areas were obliged to go out to work and share the economic hardships along with male relatives (ALIDOU, 2011, p. 53). In rural areas, due to the intensive nature of labor needed in subsistence agriculture, women rarely if at all had a chance to go into seclusion (COLES and MACK, 1991, p. 8).

Along with economic characteristics, kulle has much in common with religious practices which constitute one of the most important aspects of Hausa life. As Miles defines, “religion is the overarching feature of social life in rural Hausaland; it overshadows even language, history, culture, and economic base as a social cement” (MILES, 1994, p. 248). Roberta Dunbar (1991, p. 87) also shares its significance and states that “the fusion of Islam and pre-Islamic custom in Niger has been profound… In marriage women gained formal rights to protection, maintenance, and inheritance.”

Inheritance rights regulated under the provisions of Maliki Islamic law played a pivotal role in securing women’s economic and social position during and after the colonial period. For example, the Hausa community in the Maradi region of Niger became increasingly dependent on peanut trade where female traders were marginalized and virtually excluded from the information, credit, transport, storage, and trade institutions under colonial rule. This in turn prompted women to rely more heavily on Maliki law to claim their stakes in the family (COOPER, 1998, p. 32).

According to Beverly Mack (2011, p. 20), Holy Qur’an repeatedly emphasizes equality between men and women. But despite this fact, which presents women an opportunity to enjoy the rights and privileges, Islamic law in Hausa society did not always support women for some particular reasons. One of the reasons was the distortion of women’s rights in Islam by local traditions to favor men (YUSUF, 1991, p. 92). At times it was deliberately interpreted in such a manner to deprive women of their legal rights.

EDUCATIONAL LIMITS

Without a doubt, education, as well as socialization, marriage, and public life of Hausa were influenced over time by the interaction of Islamic teachings and indigenous traditions. Western norms target specific policies brought by the colonial powers did not assist women to elevate their position but rather further altered both expectation and practice (DUNBAR, 1991, p. 72).

Based on the Eurocentric perspective of masculinity and unwillingness to confront the patriarchal nature of the local system, colonial powers failed to recognize and support the significance of titled positions for women. This neglect further deteriorated with the exclusion of women from education. This notion was extended by colonial powers under the influence where patriarchal systems of Islamic societies have privileged the education of boys and men (MACK, 2011, p. 21).

The European educational system in Hausaland was introduced with an aim of “exposing children to a more secular and modern education” (MILES, 1994, p. 228). British, as well as French authorities, tried to discourage the Christian missionary activity in the Hausa region, although at the early stages of colonialism such missions were the primary tools in spearheading educational objectives.

According to James Coleman, as late as 1942 more than ninety-nine percent of the schools and ninety-seven percent of the students were under the command of Christian missionary schools (COLEMAN, 1960, p. 113). In addition, Europeans believed that better education would prompt Hausa to join nationalistic opposition and challenge the colonial power, as was already the case in southern Nigeria (CALLAWAY, 1987, p. 137).

Even the limited efforts of the colonial authorities to introduce Western-type schooling originally had very egoistic intentions. The French colonial government introduced its schools partly to promote its policies of cultural and linguistic assimilation and partly to produce male clerical support for its local administration (ALIDOU, 2011, p. 48). One of the basic reasons for the British was to educate the children of local chiefs and aristocracy to reinforce the respect and support for the authority of the Indirect Rule, the system which these children were expected to eventually inherit (PITTIN, 2002, p. 346).

Following the independence, the attitude of the Hausa society did not substantially change. The deep-rooted negative association of Western education with colonialism still exists and locals perceive secular education as disruptive to their traditional customs, norms, and beliefs (MILES, 1994, p. 231). This attitude continues to put young girls in a disadvantageous position where they being deprived of educational opportunities have to get married as soon as they reach puberty age (COOPER, 1997, p. 17).

SOCIAL LIFE

According to some authors, marriage under Islamic norms is considered to be ideal. The husband, as the head of the family, is responsible for food, clothing, lodging and everything else, to maintain his wife and children (DUNBAR, 1991, p. 74). Most Muslim Hausa girls marry at the age of 15 which of course negates the possibility of emotional attachment. Such marriages, according to Heike Behrend, are not generally founded on love and happiness but instead on the production of children. She further argues, that in northern Nigeria, “the threat of passionate love was counteracted by various social strategies, such as arranged marriage and sexual segregations” (BEHREND, 2011, p. 183-184). This is a very narrow-minded approach. The uniqueness and multifaceted character of Hausa marriage can be best described in Barbara Cooper’s words who states that “marriage and discourses about marriage turned out to be the site of tremendously complex negotiations, competing interests, confusions, and compromises” (COOPER, 1997, p. xviii).

After marriage, women are secluded within their households, and since their role in farming has diminished with the introduction of cash crops and taxation, and due to the exclusion from the public service, they mainly engage in domestic labor. But as Renee Pittin underlines:

Hausa women work. They work within the home as wives and mothers, as caregivers to elderly or ill kin or affines, and as processors of agricultural produce for which they may or may not receive recompense (PITTIN, 2002, p. 14).

Secluded women with the help of their children, among other things, cook and sell food, conduct petty trade, sew or weave clothing, pound grain, plait hair for other women, and work for a wage for other women (COLES, 1991, p. 172). Despite seclusion, Hausa women believe they are better off than peasant women out on the field that have to farm the land, fetch water, carry firewood, and be able to raise children and do the housework (CALLAWAY, 1987, p. 61).

POLITICAL EXCLUSION

The legacy of colonial policies concerning the exclusion of women from political life has carried on into the postcolonial era. According to Ousseina Alidou (2011, p. 41), under French colonial rule, women were not welcomed in political participation and barred from subordinate positions that were open to colonized men. She also believes, that there is no doubt “that the prevailing ideology during the colonial period was hegemonic, articulated in gendered policies that circumscribed women’s participation in the production and consumption of knowledge and promoted patriarchal biases that accompanied those processes” (ALIDOU, 2011, p. 50).

In present days, even though the Nigerian constitution forbids discrimination based on sex, women find it difficult to achieve equality with men in the political arena due to the resistance of those in power (YUSUF, 1991, p. 90). There number of middle-ranking Hausa-Fulani women professionals and female administrators in decision-making organs of government, both at the state and federal levels, is still severely limited (YUSUF, 1991, p. 92).

One of the few supporters of women’s rights in Nigeria was the leader of the People’s Redemption Party Aminu Kano, who made the position of women a basic concern for his political party. He advocated for universal direct suffrage, including the enfranchisement of women, replacement of class-based and hierarchical structures upon which the British had tried to build (CALLAWAY, 1991, p. 147). Kano further argued that domestic seclusion of women did not necessarily mean that women should be secluded from the political process (CALLAWAY, 1991, p. 150).

Another proclaimed Nigerian oppositional leader Isa Wali also propagated the proper role of women in public authority from a religious standpoint by stating that “There is nothing in Islam which prevents a woman from following any pursuits she desires. There is no distinct prohibition against her taking part in public leadership, as Aisha, the Prophet’s widow, demonstrated” (CALLAWAY, 1991, p. 149). Among prominent Muslim women of Niger, advocating for women’s rights, there is Malama A’ishatu Hamani Zarmakoy Dancandu. As an accomplished poet, she had made important contributions to Qur’anic neighborhood literacy projects for Muslim women and girls (ALIDOU, 2011, p. 42).

Political support led to the emergence during the 1990s of new Islamic feminist discourse based on women scholars’ interpretation of the Qur’an stressing the full equality of women and men across the public-private sphere (BADRAN, 2011, p. 194). Institutional and organizational support for the new movement is provided by Women Living under Muslim Laws (WLUML) and the Federation of Muslim Women’s Associations of Nigeria (FOMWAN) established in 1984 and 1985 respectively (BADRAN, 2011, p. 195).

Although the number of women in the political sphere of Niger and Nigeria is still relatively low, both countries are implementing measures to break the existing barriers. The government of Niger, for example, adopted an Act introducing a quota system guaranteeing women 10 percent of the seats in the National Assembly and 25 percent in all other governmental institutions (SKAINE, 2007, p. 124). Nigeria is trying to meet a 30 percent quota for women’s inclusion in the government which is, unfortunately, has not been successful so far (SKAINE, 2007, p. 126).

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Considering the above-mentioned developments, can it then be argued, that if given a proper chance, women could have had established such institutions or formed identical movements much earlier? Probably yes, because the religious, cultural, and social environment was already in place for many centuries, and historically Hausa women have enjoyed much wider rights and privileges. For instance, Catherine Coles and Beverly Mack (1991, p. 9) contend that often when Islamic prescriptions and Hausa cultural norms conflicted, the latter prevailed. Both men and women selectively applied Hausa norms, as opposed to those proposed by Islam, when it was advantageous for them.

Colonial impact and policies affected the future path of development for independent Niger and Nigeria. Their economies that heavily depend on commodity exports as the main revenue-generating source are very vulnerable to sudden price fluctuations on the world market. Moreover, they have also suffered because of the global financial crisis. All these factors contribute to the growing constraints on the well-being of individual households. With men losing their jobs in public and private spheres, women are spending more on the household than ever before. Women, using their savings, are buying food and fuel, paying for children’s clothing and school supplies, and frequently giving money to their unemployed husbands (Coles, 1991, p. 183).

Economic trends, better educational opportunities, and greater political activism are helping Hausa women to become teachers, nurses, government workers, and other waged laborers. And as Catherine Coles (1991, p. 187) notes, “The fact that increasing numbers of Muslim Hausa women are moving into these settings, and that at least some Hausa males support women’s efforts, suggest that current changes are neither temporary nor likely to be reversed.”

REFERENCES

ALIDOU, O. Rethinking Marginality and Agency in Postcolonial Niger: A Social Biography of a Sufi Woman Scholar, in Badran, M. (ed.). Gender and Islam in Africa: Rights, Sexuality, and Law. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 41-68, 2011.

BADRAN, M. Shari’a Activism and Zina in Nigeria in the Era of Hudud, in Badran, M. (ed.). Gender and Islam in Africa: Rights, Sexuality, and Law. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 191-210, 2011.

BADRAN, M. (ed.). Gender and Islam in Africa: Rights, Sexuality, and Law. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011.

BEHREND, H. Titanic in Kano: video, Gender, and Islam, in Badran, M. (ed.). Gender and Islam in Africa: Rights, Sexuality, and Law. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 173-189, 2011.

BODMAN, H. and TOHIDI, N. (eds.). Women in Muslim Societies: Diversity Within Unity. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1998.

CALLAWAY, B. J. Ambiguous Consequences of the Socialization and Seclusion of Hausa Women. Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 22, pp. 429-450, 1984.

CALLAWAY, B. J. Muslim Hausa Women in Nigeria: Tradition and Change. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1987.

CALLAWAY, B. J. The Role of Women in Kano City Politics, in Coles, C. and Mack, B. (eds.). Hausa Women in the Twentieth Century. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 145-159, 1991.

CALLAWAY, H. Gender, Culture, and Empire: European Women in Colonial Nigeria. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 1987.

CIA. Nigeria. 2021. Available at: https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/nigeria/#people-and-society (Accessed: September 09, 2021).

COLEMAN, J. Nigeria: Background to Nationalism. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1960.

COLES, C. Hausa Women’s Work in a Declining Urban Economy: Kaduna, Nigeria, 1980-1985. Hausa Women in the Twentieth Century. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 162-191, 1991.

COLES, C. and MACK, B. Women in Twentieth-Century Hausa Society. Hausa Women in the Twentieth Century. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 3-26, 1991.

COLES, C. and MACK, B. (eds.). Hausa Women in the Twentieth Century. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1991.

COOPER, B. Marriage in Maradi: Gender and Culture in a Hausa Society in Niger, 1900-1989. Portsmouth: Heinemann, 1997.

COOPER, B. Gender and Religion in Hausaland: Variations in Islamic Practice in Niger and Nigeria. Women in Muslim Societies: Diversity Within Unity. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, pp. 21-38, 1998.

DUNBAR, R. Islamic Values, the State, and the Development of Women: The Case of Niger. Hausa women in the twentieth century. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1991.

ENCYCLOPEDIA BRITANNICA. Hausa People. 2021. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hausa (Accessed: September 29, 2021).

MACK, B. Royal Wives in Kano, in Coles, K. and Mack, B. (eds.). Hausa women in the twentieth century. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 109-129, 1991.

MACK, B. Muslim Women’s Knowledge Production in the Greater Maghreb: The Example of Nana Asma’u of Northern Nigeria, in Badran, M. (ed.). Gender and Islam in Africa: Rights, Sexuality, and Law. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2011.

MILES, W. Hausaland Divided: Colonialism and Independence in Nigeria and Niger. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1994.

PITTIN, R. Women and Work in Northern Nigeria: Transcending Boundaries. New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2002.

SKAINE, R. Women Political Leaders in Africa. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2007.

WOLFF, E. H. Hausa Language. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Hausa-language (Accessed: September 09, 2021).

WORLD ATLAS. Who are the Hausa people? 2021. Available at: https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/who-are-the-hausa-people.html (Accessed: September 09, 2021).

YUSUF, B. Hausa-Fulani Women: The State of the Struggle, in Coles, K. and Mack, B. (eds.). Hausa women in the twentieth century. Madison: The University of Wisconsin. Press, pp. 90-106, 1991.

[1] Master of Arts in History and Political Science, Bachelor of Arts in Political Science. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3699-963X

Submitted: September, 2021.

Approved: November, 2021