ORIGINAL ARTICLE

SANTOS, Humberto de Faria [1], BRONZATO, Anderson [2]

SANTOS, Humberto de Faria. BRONZATO, Anderson. Car Wash Operation and Odebrecht: A case that will end?. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 06, Ed. 02, Vol. 10, pp. 61-75. February 2021. ISSN:2448-0959, Access link in: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/ethics/car-wash, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/ethics/car-wash

ABSTRACT

Individuals and organizations of different types are always challenged to decide by which kind of ethical framework they will abide by. The decision may be rewarding or punitive. External agents, like communities, may influence how the decision will result. This essay claims that Odebrecht corruption scandal bears an example of such a situation. Coupled with the company’s internal decisions, the external community played a role in moving Odebrecht from being a respected player in the global construction industry to the exposition of its immoral practices. The present study also demonstrates the recent attempts at political interference in the investigations of this scandal and how former Odebrecht is trying to rebuild itself as a company.

Keywords: Car Wash Operation, Odebrecht, Corruption, Latin America.

1. INTRODUCTION

The objective of this essay is to introduce the Brazilian construction company Odebrecht’s corruption case and analyze it from the perspective of the framework that led Odebrecht to act in one of the greatest corruption cases in Latin America. The analyses will focus on two driving considerations in the decision-making process that led to the case: (1) Odebrecht’s assumptions about national and international communities; (2) the absence of ethical practices motivated either by ethical principles (positive aspect) or economic incentive (negative aspect). The linkage between Odebrecht’s relations to national and international communities will be analyzed against the moral frameworks of negative and positive elements in ethics. It will stand as an argument to explain Odebrecht’s misstep. Odebrecht’s case is particularly rich not only because of the sum of money involved, US$ 800m in bribes over the last 15 years but also because of its geographic scope, which encompassed 12 countries in Latin America and Africa (RUSSEL, 2017). Furthermore, its systematic method and, finally, the cultural environment in which the company operates provide elements that enrich the case analysis. One aspect of this environment unperceived by Odebrecht’s executives is the change in society’s interest in corruption cases. It is also relevant to remark the relation of the Odebrecht case and Operation Car Wash, which is considered the most considerable anti-corruption investigation in the history of the Americas (ROMERO, 2017, p. 2). There are cases of corruption involving Odebrecht all over Latin America and Africa, these cases will be mentioned, but the main focus of this essay is the case evolution in Brazil.

2. FUNDAMENTALS

2.1 THE COMPANY

Odebrecht was founded by Norberto Odebrecht in 1940 as “Construtora Norberto Odebrecht” and became the leading construction company in Latin America, operating in 27 countries worldwide (ROMERO, 2017, p. 1). In 2015 the group employed 181,000 people all over the world. Odebrecht was recognized along with its successful history as an example of management. In one of its 2015 articles, The Economist magazine emphasized the company’s two sides (“PRINCIPLES AND VALUES,” 2015, p. 55), in other words, the fact that the company’s reputation amongst specialist was highly regarded while its real practices that have been unveiled, proved that it failed to abide by any acceptable ethical standards. As examples of the favorable international reputation, in 2010, IMD, a Swiss business school, appointed the company as the world’s best family firm.

One year before, Mckinsey, an American Consulting firm, had reported about Odebrecht that “Principles and values have helped this Brazilian family-owned conglomerate thrive.” (“PERSPECTIVES ON THE FOUNDER AND FAMILY-OWNED BUSINESSES,” n.d., p. 43). The Odebrecht family had already been building in Brazil even before Norberto founded the company. Norberto combined a management philosophy based on Protestant Lutheran ethics and Peter Drucker’s, and American management guru, teachings (“PRINCIPLES AND VALUES,” 2015, p.1).

2.2 ODEBRECHT´S CORRUPTION CASE

Odebrecht executives organized a department named the “Division of Structured Operations.” Today this unit is called by the Brazilian and international media that follow the company’s scandal the “Bribe Department” (“THE ODEBRECHT SCANDAL BRINGS THE HOPE OF REFORM,” 2017, p. 1). Money flowing from this department helped to define elections of presidents in six countries in Latin America. Besides giving financial support to the campaigns, Odebrecht also provided specialized consultancy to candidates running for the presidency in countries like Brazil, Argentina, Panama, and others. From the total US$ 7 million payments to the Brazilian advising company, Polis, US$ 3 million were directly related to election campaign advice (ROMERO, 2017, p. 2). The scheme’s core was to pay bribes to public authorities and public company executives to guarantee that Odebrecht would win fake auction launched by these companies. In Brazil, prosecutors oversaw the scheme of US$ 22.18 million in bribes to assure eight contracts with Petrobras, a Brazilian oil company (“BRAZILIAN FIRMS TO PAY A RECORD $3.5 BILLION PENALTIES IN A CORRUPTION CASE,” 2016). One other part of the scheme was to bid low offers to win contracts under the assurance that all addenda to the contracts would be approved. For instance, 22 addenda were applied in the construction of the road linking Brazil and Peru. The original cost rose from US$ 800m to US$ 2.3bn (“THE ODEBRECHT SCANDAL BRINGS THE HOPE OF REFORM”, 2017, p. 1).

Judging by the length of time of the corruption and the systematic way the company dealt with these schemes, it is possible to assert that the company’s executives were clearly and systematically committing illegal acts. These acts were not a consequence of negligence; just the contrary, it can be said that the executives were specialized in corruption or that corruption was their way of doing business. Considering its international reputation related to its management competency, it is hard to say that Odebrecht’s executives lacked information or did not master decision-making processes.

2.3 WHAT WENT WRONG? THE ROLE OF THE COMMUNITIES

How did the company move from protestant-based ethics to eliciting one of the largest scandals in history? Wicks and Parmar (2009, p. 2) offer a theory that can be employed as a tool to the analysis of the Odebrecht case. In his text, he lists different communities that can play a role in each case. These communities are the firm, the industry, the business, the local community, the national community, international community. In the words of Wicks and Parmar (2009, p. 3), “particularly in the international arena, having participants from multiple communities may entail that business have to wade through very different and sometimes conflicting sets of moral expectations.” The conflict between the morality of the firm and society and within the societies may and, in Odebrecht’s case, provoke pressure against the characters involved in corruption cases. To adapt the theory to this context, only the national and international communities will be directly covered in this essay. The other organizations are somehow addressed indirectly in different parts of the texts.

In 2014 Brazilian Federal Policy launched Operation Car Wash. This Operation unveiled, amongst other cases from different companies, Odebrecht relations within the political system, and, at the same time, arose the society indignation and pressure against this sort of relations. Both the public and the press reacted before the perception that, besides the unjust way of doing business, even the country’s leaders’ election process was being influenced if not controlled by the economic power of Odebrecht.

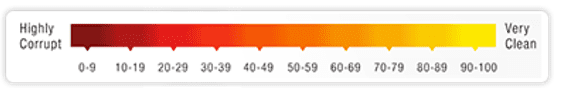

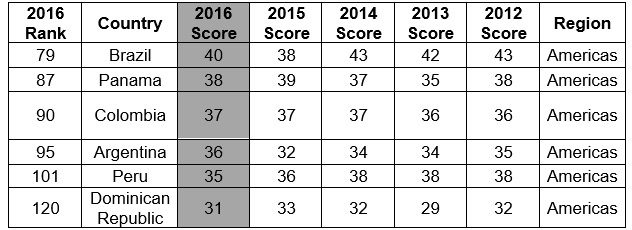

The tolerance for corruption traditionally present in Brazil and Latin America, in general, allowed Odebrecht to apply its corruption-based way of doing business in the region. Taking the Transparency International annual report as a reference for corruption, all countries involved in the Odebrecht case appear on the highly corrupt side of the index (“CORRUPTION PERCEPTION INDEX 2016,” 2016, p. 2 and 3) (see Attachment II). A national community in this analysis, in the Brazilian case, is to be split into two segments: political class and civil society. One drive consideration behind Odebrecht’s decision to operate in the bribe schema was its assumption that its relationship with the political class would keep it safe in the present and the future as it had been for the latest 15 years. For this reason, the company’s attention was turned to this public segment of the national community. Odebrecht’s executives failed to realize that the civil society was getting intolerant with corruption and that it could play as a stakeholder. And it did. From social media publications to demonstrations and official petitions, Operation Car Wash got support from civil society. As the Economist article posits, “In Latin America, we are in an era in which public opinion is playing a fundamental role in fighting corruption” (“THE ODEBRECHT SCANDAL BRINGS HOPE OF REFORM,” 2017, p. 3).

Odebrecht apparently has been tried to incorporate the principle advocated by John Ladd that “it is improper to expect organizations to conduct to conform to ordinary morality” (LADD, 1970, p. 499). An influential part of the Brazilian society stood closer to K. Goodpaster’s position, as he criticizes Ladd’s line of thought (GOODPASTER; MATTHEWS 1982, p. 3). This sort of conflict and its consequences are elements Odebrecht was not counting on.

The participation of the international community proved relevant in suppressing the scheme as well. This is another aspect which consequences Odebrecht seems to have ignored. The financial cost of this cooperation for Odebrecht will be US$3.5 billion in settlement to authorities in Brazil, Switzerland, and the United States. Another consequence, besides all the fines, relates to the caution of banks extending new loans while the controversy rages (“PRINCIPLES AND VALUES,” 2015, p. 2). As reported by Reuters (“BRAZILIAN FIRMS TO PAY A RECORD $3.5 BILLION PENALTIES IN A CORRUPTION CASE,” 2016), international cooperation, particularly from countries with strict practices regarding corruption, like the United States, was vital to elucidate the case.

2.4 WHAT WENT WRONG? THE LACK OF ETHICAL STANDARDS

In her article “Does Ethics Pays,” Lynn Paine makes the economic case for corporate ethics in two aspects: positive and negative (2000, pp. 321 e 322). Negative being the search to comply with the law and avoid financial risk and reputational exposure. On the other hand, the positive aspect seeks to go beyond mere legal observance; it aims adherence to ethical standards. By doing so, companies generate a positive environment amongst their employees and a solid reputation near the external community. Another driving consideration from Odebrecht was its contempt for the observation of formal law or common-sense ethics. By analyzing the Odebrecht case against these standards presented by L. Paine, it verifies that the company failed in meeting both positive and negative aspects. Due to social context, or national community, Odebrecht leaders neither feel compelled by law to act as to avoid punishment, negative approach nor to hold to ethical principles, positive approach, of searching of goals of its own and those of the society, also explained by Wicks and Parmar (2009, p. 9). It calls the attention that the moral deterioration in part of the community is a factor that freed the company from any minimum ethical obligation or constraint.

Part of the consequence, as aforementioned, is the economic loss that has already been measured in fines. Moreover, also associated economic loss was massive and the company’s reputation decline. Nonetheless, these are not the only losses. Marcelo Odebrecht, the former CEO of the company, was sentenced to 19 years in prison that he is already serving. Job losses, and discrimination against the company’s former employees (“Demitida da Odebrecht, ex-secretária diz ser discriminada na busca de emprego – Notícias – Política,”n.d. – {“Dismissed from Odebrecht, former secretary says he is discriminated against in his job search – News – Politics}) are also part of the price being paid.

To appoint what might have improved the decision process and led to a better outcome, it is not enough to examine the company’s process only. Considering that, as argued, the community, or one of its segments, the political one, helped create the conditions for the operation of the corruption practice, it is important to ask what the community might do differently. In the words of Romero, “the only elixir to cure this regional disease is stronger democratic institutions throughout Latin America” (2017, p. 4). Institutions, like the Brazilian judiciary, will only remain strong if supported and watched by public opinion.

Although the name has changed, Odebrecht still exists as a company, and now, for the first time, it is likely to have a non-Odebrecht as CEO. “This is an opportunity to address a problem and to express our sincere apologies to the society as a whole and reinforce the commitment that we have set things right” (RUSSEL, 2017). With these words, Flávio Faria, CEO of the Odebrecht’s Industrial Engineering Division, addressed his audience in the June 2017 edition of the engineering conference held in New Orleans. Besides espousing this speech with new practices, Odebrecht also has the challenge of fulfilling the economic commitments before Brazilian and other countries’ courts. Odebrecht has implemented an ombudsman program, operated by a third party, and still, according to Faria, “the company encourages everyone, from the top down, to be ethical in their behavior” (RUSSEL, 2017). The company seems to have the intention of turning to the practice of moral values. As we saw and will see below, the case is still unfolding. It is early to evaluate the initiatives; what can be said is that given the reactions the company is still facing in different parts of the world, it is unlikely that without these initiatives, the company will have any chance to survive.

2.5 ODEBRECHT AFTER THE SCANDAL

According to Forbes magazine, over the past five years, the company has undergone the reformulation of several processes internally, as well as the methods of action, focusing on a rigorous change based on ethics, integrity, and transparency. With the promise and philosophy of being a company focused on the future, Odebrecht announced at the end of 2020 that it would be called Novonor, in an attempt to restructure that intends to remove the group from all corruption scandals in the recent history of Latin America (FORBES, 2020).

After adding a debt of more than US$ 15 billion when we deal with the 11 companies belonging to the group, in 2019, the company presented a judicial reorganization plan (similar as the Chapter 11 of United States), which was approved in the middle of 2020 by the São Paulo State Court of Justice. This was the largest judicial recovery approved by Brazil. Among the determinations, the now called Novonor will have to sell 4 of its main companies, these being petrochemical Braskem, ethanol producer Atyos, rig operator Ocyan, and participation in the hydroelectric plant Saesa (MARINHO, 2020).

Although the former Odebrecht’s reputation has been vastly affected by the scandals that revealed the systemic involvement of corruption in the “Car Wash” case, in 2018, the rig operator Ocyan, formerly Odebrecht Oil and Gas, signed a contract with Petrobras for rigging. The figures were not disclosed, but the name change, as well as changes in governance and leniency agreements with authorities clearly demonstrated a cycle of resumption of the group. On the other hand, the company reduced the number of employees by 1/3 when compared to the number of hires before the appearance of the corruption scandal (FOLHA, 2020).

The implementation of Ocyan’s improvement practices was completed in 2020 after almost four years of independent monitoring. Among the new policies, there was the implementation of anti-corruption controls and mechanisms that ensure ethics and transparency in the conduct of agreements and business (RUDDY, 2020).

Although the reporting boom occurred between 2013 and 2016, even in recent years, the literature has portrayed the study of projects in which former Odebrecht was involved in paying bribes. For example, Campos and collaborators (2019) evaluated, in a case study, that 58 projects signed by Odebrecht were underpayment of bribes, among them, the payment of employees for structuring bids in order to benefit the company or obtain a better evaluation for the project auction. Still, in this study, the authors point out that of the 58 projects analyzed, 30 were bribed to achieve profitable renegotiations; that is, many contracts increased payment to former Odebrecht without requiring additional investments or improving the quality of service (CAMPOS, 2019).

According to Valarini (2019), the use of illegal practices was encouraged by a permissive code of conduct, and by the absence of an internal system capable of preventing illegal activities by the company. As a result, organizational culture was established so that such practices were normalized and naturally accepted (VALARINI, 2019). With this culture in place, former Odebrecht made use of corrupt political culture in Latin America, creating associations with influential names in power, which culminated in political, social, and economic instability and involved countries like Peru, Bolivia, Argentina, Ecuador, Venezuela, Colombia, Panama, Dominican Republic, Guatemala, and Mexico (MORALES, 2019).

In 2018, the so-called Odebrecht implemented a “Code of Conduct” that consisted of a set of guidelines for both internal and external guidance for company employees at the interaction level, with an extremely wide range that considers the relationship with shareholders, suppliers, customers, private agents, partner companies and competitors. In addition, the implemented “Code” prohibited several attitudes that could culminate in financing or sponsoring any illegal acts, such as kickbacks and bribes, and members are required to sign a declaration of acceptance and commitment, where they must declare that they have become aware of all the provisions present in the document, and are willing to comply with them (ODEBRECHT, 2018).

2.6 POLITICAL INVOLVEMENT AND ATTEMPTS AT POLITICAL INTERFERENCE AFTER THE SCANDAL

In testimony to the Public Ministry, the former Odebrecht CEO, Marcelo Odebrecht, reported that illicit payments to Brazilian politicians and executives accounted for 0.5 to 2% of the company’s annual revenue (MARQUES, 2019). Bribes and contributions to political campaigns were paid. Payments, which took place electronically, helped to mask the evidence of bribes and established a long-term relationship between those who paid the bribe and those who received it (CAMPOS, 2019).

Scandals involving former Odebrecht have reached international proportions. For example, in 2017, Jorge David Glas Espinel, an Ecuadorian politician who was Vice President of Ecuador until 2017, used his status as Minister of Strategic Sectors and also as Vice President to benefit from contracts with former Odebrecht. After all the complaints, the international investigation prompted Glas to leave the vice presidency and, in December 2017, the politician was sentenced to 6 years in prison (DANIEL, 2019).

At the national level, the challenges for Brazilian development in terms of innovation and growth involve the country’s capacity and autonomy as an institution and, in contrast, the intense politicization of state-owned companies (OLIVEIRA, 2020). Marcelo Odebrecht, currently serving a sentence under “house arrest”, suffers from the serious consequences that have hit the company built for three generations. Evidence reveals that the corrupt root began when Norberto Odebrecht was still in charge (MORALES, 2019). In 2017, with the appointment of Luciano Guidolin as executive director, the company made a series of changes, implementing a channel for anonymous reporting of acts considered illegal, as well as a compliance policy different from that previously practiced.

Several Odebrecht managers denounced and convicted of corruption have entered into an award-winning plea agreement at the national and international levels – collaborating to investigate the scandal in countries such as the United States, Panama, Switzerland, Peru, Dominican Republic, and Brazil. In 2018, the Brazilian federal police concluded that the former president of Brazil, Michel Temer received a bribe from the former Odebrecht (MORALES, 2019).

At the same time, Jorge Enrique Pizano and Alejandro Pizano, his son, two central witnesses in the case of Odebrecht in Colombia died in the same week. Jorge theoretically committed suicide while his son was poisoned. A similar case occurred with Rafael Merchán, Colombia’s former transparency secretary, who ingested cyanide. Alan García, who was twice Peru’s former president, committed suicide by shooting himself in the head on the day he would receive an arrest warrant for having received bribes in millions by “Odebrecht Engenharia e Construção” (MORALES, 2019).

In Brazil, the judicial system has bureaucratic processes, slow and full of problems inherent to the system. These characteristics contributed to the development of an environment based on corruption and the diversion of capital. In addition, the “sense of impunity” is prevalent, and this becomes clear when we observe that, of all the corruption cases investigated in the last decades in the country, only the Car Wash Operation led to the arrest of great executives and politicians (DALLAGNOL, 2017).

The current president, Jair Messias Bolsonaro, at the end of 2020, claimed to have “ended the Car Wash”, in an attempt to carry out a self-praise, suggesting that there was no corruption in his mandate. However, in response to this statement, several prosecutors suggested moments during his government when Bolsonaro would, in theory, have acted in an attempt to weaken the Operation (SHALDERS, 2020). An example was the appointment of jurist Augusto Aras as Attorney General. Recently, Aras affirmed that it would be up to the Legislative Branch to investigate crimes of responsibility attributed to authorities, an attitude that revealed its attempt to evade the constitutionally established functional assignment (MOLICA, 2021). In addition, Aras published a decision stating that the task force in Curitiba for the operation will only have a mandate to operate until the end of January 2021. Other times when Bolsonaro allegedly tried to weaken the Car Wash, was during the resignation of ex-minister of justice, Sérgio Moro, who politically broke with the president and left the government accusing him of trying to interfere in the operations of the Federal Police, in an attempt to protect political and family allies in investigative processes, and in making important changes on the Financial Activities Control Council (COAF) (SHALDERS, 2020). Finally, the appointment of Judge Kassio Nunes Marques to the Supreme Federal Court, a judge who usually privileges the defendants’ rights and guarantees during investigations. The minister’s presence in the Supreme Court is absolutely important to absolve or reduce the sentences of politicians. When Kassio Nunes was appointed by the current president, several politicians investigated in the Car Wash Operation have been celebrated (SHALDERS, 2020). Jair Bolsonaro recently associated himself with several politicians who are targets of the Car Wash Operation and who are responsible for state sectors with billionaire budgets (PONTES, 2020).

CONCLUSIONS

This essay sought to present and analyze the Odebrecht corruption case. The analysis objective was to identify what led Odebrecht’s executives to make the decisions that moved the company from being a huge well-regarded organization to a position of international exposure. Besides that, the company was also subject to pay the highest ticket related to corruption in history. Different approaches could have been taken in this analysis. In this case, the company’s decisions were examined against the concept from Wicks and Parmar, which considers the impact on and the influence by different communities. Furthermore, the negative and positive aspects of the corporate ethics case presented by Paine were also analyzed. These approaches were used for they offer frames that guide through the partition of the case in different elements, communities and link these elements under two kinds of motivation, the positive and negative aspects. The current outcome of the Odebrecht case offers features to enforce another Lynn Paine argument of economics being a justification of ethics acceptance rather than ethics principles themselves. Whatever the motivation was for Odebrecht to act the way it did, the company is now being forced by the national and international communities to accept higher moral standards to do its business, as it did in an attempt to preserve the company’s reputation. However, it is worth mentioning that investigations of Car Wash Operation are still ongoing and that several attempts at political interference have been practiced recently in Brazil.

REFERENCES

CAMPOS, N., ENGEL, E., FISHER, R. D., GALETOVIC, A. Renegotiations and corruption in infrastructure: The Odebrecht case. Access on January 24, 2021. Available at <https://ssrn.com/abstract=3447631>.

Corruption Perception Index, 2016. In: Transparency International – the global coalition against corruption. Access on January 24, 2021. Available at <https://www.transparency.org/en/news/corruption-perceptions-index-2016#>.

DALLAGNOL, D. A luta contra a corrupção: A Lava Jato e o futuro de um país marcado pela impunidade. Primeira Pessoa, Rio de Janeiro, 2017.

DANIEL, L. G. C. Medios y Corrupción. Análisis del discurso de las noticias publicadas en los diarios El Telégrafo y El Comercio sobre el caso Jorge Glas – Odebrecht emitidas entre agosto y diciembre de 2017. (Trabajo de Titulación para obtención del título de Comunicador Social con énfasis en Comunicación Organizacional), 104 f. Quito, Ecuador, 2019.

FOLHA, 2019. Em retomada, empresa da Odebrecht aluga 1ª sonda à Petrobrás após Lava Jato. Access on January 24, 2021. Available at <https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mercado/2019/07/em-retomada-empresa-da-odebrecht-afreta-1a-sonda-a-petrobras-apos-lava-jato.shtml>.

FORBES, 2020. Odebrecht muda nome para Novonor. Access on January 23, 2021. Available at <https://forbes.com.br/negocios/2020/12/odebrecht-muda-nome-para-novonor/>.

GARCIA, D. Demitida da Odebrecht, ex-secretária diz ser discriminada na busca de emprego. In: Notícias UOL Política. Access on January 23, 2021. Available at <https://noticias.uol.com.br/politica/ultimas-noticias/2017/04/25/demitida-da-odebrecht-ex-secretaria-diz-ser-discriminada-na-busca-de-emprego.htm>.

GOODPASTER, K. E., Jr MATTHEWS, J. B. M. Can a corporation have a conscience? Harvard Business Review, 1982. Access on September 06, 2017. Disponível em <https://hbr.org/1982/01/can-a-corporation-have-a-conscience>.

LADD, J. Morality and the ideal of rationality in formal organizations. The Monist, v. 54 (4) p. 488-516.

MARINHO, F. Odebrecht consegue a maior recuperação judicial da história do Brasil. In: Economia, Negócios e Política, CPG – Click Petróleo e Gás, 2020. Access on January 23, 2021. Available at <https://clickpetroleoegas.com.br/odebrecht-consegue-a-maior-recuperacao-judicial-da-historia-do-brasil/>.

MARQUES, B. From the Panama papers to Odebrecht: illicit financial flows from Brazil. Business and Public Administration Studies, v. 12, n. 1, p. 22-31, 2019.

MOLICA, F. Senadores querem que Aras seja punido por Conselho Superior do MPF. In: CNN Brasil Política, 2021. Access on January 24, 2021. Available at <https://www.cnnbrasil.com.br/politica/2021/01/22/senadores-querem-que-aras-seja-punido-por-conselho-superior-do-mpf>.

MORALES, S., MORALES, O. From bribes to international corruption: the Odebrecht case. Emerald Emerging Markets Case Studies, v. 9, n. 3, p. 1-13, 2019.

ODEBRECHT, 2018. Codigo de conducta. Access on January 24, 2021. Available at <https://www.oec-eng.com/es/home#book5/1>.

OLIVEIRA, R. L. Corruption, and local content development: assessing the impact of the Petrobras’ scandal on recent policy changes in Brazil. The Extractive Industries and Society, v. 7, p. 274-282, 2020.

PAINE, L. S. Does ethics pay? Business Ethics Quarterly, v. 10 (1), p. 319-330.

PERSPECTIVES ON FOUNDER AND FAMILY-OWNED BUSINESSES. In: McKinsey&Company. Access on September 06, 2017. Available at <https://www.aidaf.it/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Perspectives_on_founder_and_family-owned_businesses.pdf>.

PONTES, J. Bolsonaro até queria acabar com a Lava-Jato, mas não pode. In: Veja Política, 2020. Access on January 24, 2021. Available at <https://veja.abril.com.br/blog/jorge-pontes/bolsonaro-ate-queria-acabar-com-a-lava-jato-mas-nao-pode/>.

PRINCIPLES AND VALUES. The Economist, 2015. Access on September 06, 2017. Available at <https://www.economist.com/business/2015/08/20/principles-and-values>.

ROMERO, G. A Brazilian virus called Odebrecht. Brazil, N_A.

ROSENBERG, M. RAYMOND, N. Brazilian firms to pay record $3.5 billion penalty in corruption case. In: Reuters. Access on January 24, 2021. Available at <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-brazil-corruption-usa/odebrecht-braskem-plead-guilty-in-u-s-after-brazil-bribe-probe-idUSKBN14A1QE>.

RUDDY, G. Ocyan conclui melhorias na conformidade após monitoramento externo. In: Valor Econômico, empresas, 2020. Access on January 24, 2021. Available at <https://valor.globo.com/empresas/noticia/2020/11/19/ocyan-conclui-melhorias-na-conformidade-apos-monitoramento-externo.ghtml>.

RUSSEL, P. R. Odebrecht tries to “turn the page” after bribery scandal, 2017.

SHALDERS, A. ‘Acabei com a Lava-Jato’: as medidas de Bolsonaro que já enfraqueceram a operação. In BBC News Brasil, 2020. Access on January 24, 2021. Available at <https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/brasil-54472964>.

THE ODEBRECHT SCANDAL BRINGS HOPE OF REFORM. The Economist, 2017. Access on September 6, 2017. Available at <https://www.economist.com/the-americas/2017/02/02/the-odebrecht-scandal-brings-hope-of-reform>.

VALARINI, E. POHLMANN, M. Organizational crime and corruption in Brazil a case study of “Operation Carwash” court records. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, v. 59, 100340, 2019.

WICKS, A., PARMAR, B. L. Moral Theory and Frameworks. Rochester, NY, 2009. In: Social Science Research Network. Access on September 6, 2017. Available at <https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1417202>.

ATTACHMENTS

Data on some of the consequences of the reflection of Operation Car Wash in other Latin America countries.

| Country | Bribes paid (in millions of US$) | Fines | Charged | Detained |

| Argentina | 35 | 0 | 0 (1 under investigation | 0 |

| Colombia | 11 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Dominican Republic | 92 | 184 | 0 | 0 |

| Panama | 59 | 59 | 17 | 0 |

| Peru | 29 | 262 | 4 | 4 |

Source: article A Brazilian Virus Called Odebrecht. February 2017

Excerpt from the Corruption Perceptions Index 2016

[1] Mestre em Sistemas de Gestão e Estudante de PhD em Educação Profissional.

[2] Candidato ao Mestrado em Tecnologia da Informação, Pós-Graduação Lato Senso em Perícia Judicial e Práticas Atuariais com docência em Ensino Superior, Pós-Graduação Lato Sensu em Controladoria e Finanças e Bacharel em Ciências Contábeis.

Enviado: Janeiro, 2021.

Aprovado: Fevereiro, 2021.