ORIGINAL ARTICLE

SOUSA, André Laurent Souza Lopes [1], SANTOS, Ana Lucia Prado Reis dos [2], DENDASCK, Carla Viana [3], OLIVEIRA, Euzébio de [4], BAHIA, Mirleide Chaar [5]

SOUSA, André Laurent Souza Lopes. Et al. Far beyond the hook: Science and football in the sports coverage of Pará. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 05, Ed. 03, Vol. 11, pp. 135-167. March 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access Link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/communication-en/far-beyond-the-hook, DOI: 10.32749/nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/communication-en/far-beyond-the-hook

SUMMARY

Reports relating science and football are not frequent in the sports coverage of Pará. Understanding the causes of this problem is the main objective of this study. From the literature review of sports science in soccer, the interdisciplinarity that for decades contributes to relevant studies that resulted not only in the understanding of problems of the sport, but also in the increase in the performance of soccer players and teams. In a second moment, the work brings the dialogue between scientific culture (VOGT, 2003) and journalism, from the perspectives of scientific (BUENO, 2009) and sports journalism (BUENO, 2005; MALULY, 2005), in order to highlight the provocation of Messa (2005), which credits sports journalism of a scientific character, sports-scientific journalism, the possibility of going beyond entertainment for fans-spectators. However, it is necessary to understand, from semi-structured interviews, the limiting factors of sports coverage in Pará and the reasons for science to have little space. One possibility to expand the content involving science and football is the expertise and relationship between journalists and members of the technical committees of the football teams of Pará.

Keywords: sports science, scientific dissemination, scientific journalism, sports journalism.

INTRODUCTION

Once, an experienced broadcaster said in the broadcast of the match between Paysandu and Castanhal, on February 25, for the Campeonato Paraense 2018, after Pedro Carmona was replaced in the first half: “he felt a hook in the left thigh”. At the press conference, after the match, the then coach of Paysandu, Dado Cavalcanti, showed concern about the sprained knee of Carmona. The club did not provide a doctor to give interviews to journalists.

The season was still in the beginning. The team had played only the ninth of the 61 matches of the 2018 season and had already undergone a change in the technical committee (Dado Cavalcanti was hired to replace Marquinhos Santos). The next day, Carmona was diagnosed with a medial collateral ligament (CML) injury. At the time, the headlines highlighted Carmona’s absence from training, the test result and the time he would be in recovery: 30 days. A clue of what could have caused the injury boiled down to a slide on the lawn. Although he did not undergo surgery, Carmona took longer, about three months, to be able to return to play.

For Villardi (2004), constant changes in technical commissions stem from the need for clubs to achieve short-term results. However, these changes modify training methods, making it impossible to develop an individualized work program, including for groups of athletes with similar characteristics.

The effect of abrupt changes in workload and non-observation of individuality and specificity in training, added or not to predisposing facts, can cause the balance between the absorption capacity of repetitive stimuli and the threshold of each individual, determining lions by excessive use (VILLARDI, 2004, p. 173).

Sports coverage, in situations like this, often diverts the way from good sports journalism to entertainment. The causes of the injury lose ground for the time when it will embezzbe the team. The show takes the lead due to the ease of news crossing the line of entertainment.

Just as the injury cannot be seen in isolation (VILLARDI, 2004), football and the sport also do not. Starting with the introduction of Physical Education in Brazil, which resembles the interests of the ruling classes of the countries of Europe. Suffering, also, influence of positivist theories, the idea of forming strong, healthy and important individuals for the development of the nation can be observed in laws, which emerged with the intention of valuing the spirit of nationalism. In the words of President Vargas, “increase the civic education of the new generations by organizing youth in order to constitute an easily mobilized reserve, whenever there is a patriotic objective to be achieved” (CASTELLANI FILHO, 2006, p. 89).

In the military period, when this intervention intensified, in addition to nationalism, there were other pretensions, both political and economic. The new championship was also used in the National Integration Plan, serving to integrate clubs from several Brazilian states, placing in the competition teams from the regions where the Arena was bad in the polls, in order to win votes, which led to the incredible number of 94 clubs (from 21 of the then 22 states) in the 1979 championship edition, at the time when the Brazilian Sports Confederation (CBD) was commanded by Heleno Nunes. The construction of grand football stadiums in regions where the sport was not popular or the Arena was unpopular, was very frequent.

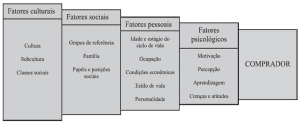

Football has also been business, as Mário Gobbi, then president of Corinthians/SP, once said, by justifying the sale of three important players from the team that won the Campeonato Paulista and the Copa do Brasil in 2009. Almost ten years later, Gobbi classified it as a very strong phrase for our culture, regretted it and withdrew what he said. However, economic aspects continue to enter into the composition of the game and media coverage. A report on the website “Valor Econômico” reveals the size of this market: the revenue of the country’s top 22 football clubs grew 2.7% in 2017. In the previous year, the increase was even higher: 30%. With this, these clubs totaled a revenue of R$ 5.11 billion. Those who manage to get their finances up to business and adopt good governance practices will be able to form an elite within the elite of Brazilian football in the coming years, with decisive repercussions on the cash and on the pitches.

Thus, the central objective of this work is to understand why sports coverage in Pará reserves so little space for science in sport. From an interdisciplinary bibliographic review of sports science in football, the dialogue with concepts of scientific culture and journalism is contextualized, especially scientific and sports, which at first appear to have no connections beyond specialized journalism, but, as Messa (2005) provokes: is it possible to do sports journalism with a scientific character?

Thus, we sought to know the profile of journalists and broadcasters working in the media outlets of Pará, understand the routine of the newsrooms and identify the factors that limit and delimit the issues that will be on the agenda in sports coverage. For this, 16 professionals who are associated with ACLEP (Association of Chroniclers and Sports Announcers of Pará) had answered semi-structured interviews.

Some findings were already expected, it is quite true. The science of sport is not on the agendas and the football of Clube do Remo and Paysandu Sport Club hold hegemony in the sports coverage of Pará.

However, the data analysis helped to dismantle two hypotheses: the first that the professionals disagreed that science was present in sport and, therefore, would not identify the ways in which it manifests itself in the day-to-day training and football matches. The central point is the divergence that has been established is in the perception of the audience, where the debate questions whether readers, viewers and listeners have an interest in science in sport.

From the dialogues of this work it is possible to suggest a first step for sports journalism of a scientific nature. The application of scientific knowledge to sport is one of the functions of professionals who make up the technical committees of football teams. Therefore, the relationship between journalists and broadcasters and technical committees is a way to reach this goal. After all, professionals who have links with academies and research institutions in Pará are rare. It is possible to establish a relationship not only of journalistic source, but also of a source of scientific knowledge, also based on scientific culture. It is possible, yes, to go beyond the hook.

METHODOLOGY

According to the Association of Chroniclers and Sports Announcers of Pará (ACLEP), the state has about 150 professionals registered and able to apply for accreditation in games organized by the Brazilian Football Confederation (CBF) or Federation of Paraense Football (FPF). According to Article 6, paragraph VII of the General Regulation of CBF Competitions, it is expressly up to the federations to approve the lists forwarded by local entities of representative classes of professionals scheduled to work, with the objective of accrediting and supervising access to the stadium and lawn (CBF, 2019).

Despite the difficulty in specifying relevant information, such as communication vehicles and sports programs that participate in the coverage of football matches organized by the FPF and CBF, ACLEP presented a timid overview of accredited professionals and associates who work directly in the coverage.

Table 1: Classification of Professional Roles

| Function | Amount |

| Reporter | 36 |

| Editor | 20 |

| Narrator | 18 |

| Commentator | 10 |

Source: ACLEP, 2019

From these data, 16 professionals were selected for the application of semi-buried interviews. The choice was of the non-probabilistic type, intentional by criteria of representativeness and accessibility (BRUYNE et al., 1977). The number of participants was defined based on the criterion of data saturation, that is, when the answers became repetitive, the application of the interviews is terminated, since, “qualitative research can use random resources to fix the sample. That is, it seeks a greater representativeness of the group of subjects who will participate in the study” (TRIVIÑOS, 1997, p. 132).

This paper defined as qualitative methodology the application of semi-structured interviews (semi-directive or semi-open), in which “open and closed questions combine, where the informant has the possibility to discuss the proposed theme” (BONI & QUARESMA, 2005, p. 75), observing what Lakatos proposes (1996) in relation to the interviewee’s choice, the opportunity of the interview and the preparation of the script with the main questions , and recognizing that one receives the informant’s portrait of the world, and it is up to the researcher to evaluate the degree of correspondence the statements of objective or factual reality (BONI & QUARESMA, 2005). Thus, the semi-structured interview follows the historical-cultural theoretical line (dialectic), with the objective of determining direct and indirect rations, not only favoring the description of social phenomena, but also explanation and understanding of totality, besides maintaining the conscious and active presence of the researcher in the process of information collection (TRIVIÑOS, 1987).

For this study, the following criteria were considered for the definition of the interviewees: (i) Interviewing at least 10% of the accredited professionals or members of ACLEP; (ii) Contemplate all types of vehicles (TV, radio, print and web); (iii) Interview at least one woman of each type of vehicle (TV, radio, print and web); (iv) Consider the integration of media (TV and web; print and web), diversify functions, pay close to the accumulation of them (reporter and presenter; editor and producer) and observe professional experience (beginners, experienced and veterans).

Thus, a heterogeneous sampling was composed, with men and women who recently entered the job market or are approaching 50 years of career; work in AM, FM and web radios, commercial and public TV stations, printed newspapers that are also distributing content also over the internet from news sites; have started their careers in radio and are on TV; formed or are in academic training in Journalism or other areas that are not linked to social communication, without disregarding those who did not have the opportunity to go through the Academy; and accumulate two or more functions in the newsrooms.

Table 2: List of professionals interviewed

| Name | Function | Vehicle | Age | Career | Training |

| Agripino Furtado | Reporter | Liberal Radio | 67 years old | 47 years old | Full Medium |

| André

Júnior |

Commentator | Metropolitan Radio | 27 years old | 11 years old | Superior Complete (Administration) |

| Andréia Espírito Santo | Reporter | Liberal Journal | 29 years old | 9 years old | Superior Completo (Journalism) |

| Bruna

Dias |

Reporter | DOL Website | 30 years old | 6 years old | Superior Completo (Journalism) |

| Carlos Ferreira | Columnist and Commentator | Liberal Newspaper and Liberal TV | 54 years old | 38 years old | Complete Superior (Social Sciences) |

| Carlos

Felipe |

Editor | Liberal Journal and oliberal.com | 29 years old | 10 years old | Superior Completo (Journalism) |

| Edson Oak | Reporter and Presenter | TV Record | 33 years old | 11 years old | Superior Completo (Journalism) |

| Guilherme Guerreiro | Administrative and commercial director | Radio Club and RBA TV | 59 years old | 45 years old | Superior Complete (Right) |

| Lauany Chaliê | Reporter | Astral Web Radio | 31 years old | 1 year | Superior Completo (Journalism) |

| Name | Function | Vehicle | Age | Career | Training |

| Magnus Fernandez | Producer and Commentator | Radio Club and Website radioclube.com.br | 31 years old | 14 years old | Incomplete Superior (Journalism) |

| Marcelo Dinelly | Producer | TV Liberal | 28 years old | 4 years old | Superior Completo (Journalism) |

| Mariana Malato | Editor and Presenter | RBA TV | 28 years old | 5 years old | Superior Completo (Journalism) |

| Marquinho Belém | Commentator | Radio Club and TV Cultura | 43 years old | 7 years old | Technical Level (Radio Host) |

| Max

Sousa |

Reporter | CBN Amazon Radio | 25 years old | 5 years old | Incomplete Superior (Journalism) |

| Paloma Andrade | Broadcast Coordinator | CULTURE TV | 39 years old | 18 years old | Superior Completo (Journalism) |

| Valmir Rodrigues | Narrator and presenter | Radio Club and TV Cultura | 49 years old | 32 years old | Incomplete Superior (Journalism) |

Source: Own authorship, based on data collected in semi-structured interviews.

Thus, it was possible to know the professional profile and routine and identify the factors that limit and delimit the issues that will be sports coverage in Pará.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS

The reporter Agripino Furtado of Liberal Sports, program of Liberal Radio that has more than six hours of programming divided into four daily editions, reveals the size of the space destined to the football news of Remo and Paysandu. According to the experienced broadcaster, the program brings the news of Paysandu and Remo, the Football Federation (paraense), in addition to the results and tables of national and international competitions. In addition, “the program still has the participation of commentators who analyze the news and (sporting) facts of the day” (FURTADO, 2019, verbal information).

However, sports coverage has not been presented in Pará exclusively journalistic. For commentator André Chaves Júnior, 27, journalism and entertainment are present in the Metropolitan Sports program, radio Metropolitan. For Chaves Júnior, the part of sports journalism is represented by analysis and information. The entertainment part involves football itself (JÚNIOR KEYS 2019, verbal information). In this sense, Guilherme Guerreiro, director of sports administrator and commercial radio club and presenter of RBA TV, there is another function to be played that brings the professionals closer to a show man.

I find myself in this world with journalistic responsibility, checking the news, but we develop entertainment. We have an obligation to take care of the news, the basis of credibility, with transparency and reliability of the public. But we have to be aware that we are dealing with a product that is also exciting (GUERREIRO, 2019, verbal information).

This relationship also exists in the edition of the program produced by TV Liberal, globo affiliate in Pará. Marcello Dinelly Júnior, a producer who began his career in the sports publishing company of the station four years ago, believes that Globo Esporte is a program both entertainment and journalistic. For the young producer, sport is not journalism, it is entertainment, but “globo esporte pará reports are produced and elaborated on both levels, because it is still information” (DINELLY JÚNIOR, 2019, verbal information).

Advancing to web analysis, that is, on the internet, space marked by entertainment, journalism was absorbed as such and came to have a lighter face, according to reporter Bruna Dias, of the website Diário Online (DOL). Dias’ routine provides for the production of new texts from the reports of the group’s printed newspaper, Diário do Pará. With this, the journalistic text begins to present characteristics of entertainment and “as the Daily already gives these things more journalism, training, and we reproduce, we just make cold stories, more curiosities” (DIAS, 2019, verbal information).

Thus, sports journalism would be providing a service that Dejavite (2007) calls Infotainment. It is journalism that at the same time brings a service and provides information and entertainment. The serious content is the report that brings new information, deepens and criticizes, with the purpose of reflection. Entertainment, the not serious, would only amuse, with humor, attracting the receiver by dealing with lighter subjects, lights. But that has a risk: not bringing anything new, just something old, with another outfit.

There is care in producing content with lighter language also on TV. Edson Carvalho, of TV Record presents the sports board in the General Balance Sheet, says he needs to make adaptations in the language, making it simpler, direct and even didactic not to restrict the content to the sports public. (CARVALHO, 2019, verbal information).

More experienced journalists, such as commentator and columnist Carlos Ferreira, from TV Liberal and Newspaper O Liberal, also have the mission of making the content lighter. For Ferreira, it is necessary to work in both perspectives, from the commitment of sports journalism and sport, from the perspective of lightness, in the approach. Namely: “when you fulfill your obligation? When you get your message responsibly. What about entertainment? When it gives lightness and makes that content attractive.” (FERREIRA, 2019, verbal information).

In addition, the data confirmed that the journalistic coverage largely based on the football of Clube do Remo and Paysandu Sport Club. However, it is important to highlight that the morning program Camisa 13, RBA TV, has as editorial rule cover all competitions and display, in addition to the reports on the football of Remo and Paysandu, at least two reports on sports considered amateur (such as athletics, futsal, basketball, volleyball) every day.

In other vehicles, the rule is to condition the space to other modalities to the occasion and interactivity of the fan. Max Sousa, producer, announcer and presenter of the radio program CBN Amazônia Esporte highlights this.

It focuses not only on Remo and Paysandu, we focus on other modalities. What else comes to the fore, what is more focused even is Remo and Paysandu. It is what draws the most attention, which causes the most repercussion among the fans. As we open more to the public, in the sports program, it is when we gain more audience. But in sport, as it is something that involves more the passion of Paraense, Remo and Paysandu, is when it really fills with message (SOUSA, 2019, verbal information).

In this sense, the reporter of the newspaper O Liberal, Andréia Espírito Santo justifies the sports coverage to have most of football centered on Remo and Paysandu for two reasons: the location, in the capital, and it is two great teams of the state. After all, “this draws attention and, in football, which is the main sport, we have a lot of demand in this sense” (ESPÍRITO SANTO, 2019, verbal information).

It is important to observe another important point revealed in the data analysis, which identified three main factors limiting sports coverage. The first is the number of personnel, directly related to the timing of communication companies. According to the Brazilian Press Association (ABI), there were 1,200 layoffs, including journalists, in 2016 alone.

In addition, the communication companies are integrating the newsrooms, like what happened in the Sports division of Grupo Globo. Roberto Marinho Neto, executive director of Sports, presented the changes in management, which included the new structure that integrates, in the same area, all the activities of TV Globo and Globosat, that is: the newsrooms of Globo Esporte, programs Sportv and globoesporte.com began to work in an integrated way. The phenomenon is not new and studies on media integration (MOHERDAUI, 2004) has been coming since the 2000s.

The restructuring of newsrooms and change in the routine of journalists, with professionals performing multitasking, is also a reality in the newsrooms of paraense vehicles. The most recent experience was that of the Liberal group. The newsroom of the printed newspaper received the company of the Team of Radio Liberal and began to produce content for liberal.com site (replacing the ORM Portal) in which it was self-styled integrated writing. Carlos Fellip, who previously only edited the printed sports notebook, now produces content for webjournalism (MIELNICZUK, 2003). In the routine, content produced for the site is factual and multimedia. Then, the text is expanded and distributed in the printed newspaper (ARAÚJO, 2019, verbal information).

Thus, the time dedicated to the external to monitor training and matches was reduced. “This caused reporters to stop following the training sessions and games, depending on the information collected on the internet or passed on by the press office of the clubs” (DIAS, 2019, verbal information).

Agripino Furtado also cites “difficulties in moving in training. They are far from the center and it is complicated for you to move. Sometimes we go on our own” (FURTADO, 2019, verbal information).

To go beyond training coverage and rowing and paysandu games, professionals need to make choices. The communication companies offer a maximum of two exclusive teams for sports coverage on TV, for example. For the editor and presenter of the program Camisa 13, RBA TV, covering other sports requires extra effort: “we cover amateur sport. And it still has to adapt to the agenda of Remo and Paysandu. We only have two reporters” (MALATO, 2019, verbal information).

The consequence is prioritization of the coverage of the remo-paysandu duo and the reduction of space for other sports.

We work most of the year with rowing and Paysandu, our same fort is the duo Re x Pa. We start working the amateur sport when we don’t have (Remo and Paysandu). […] Remo and Paysandu are the two clubs, but from all over the northern region, and football, as is the greatest passion of the Brazilian, also reflects this. (DINELLY JÚNIOR, 2019, verbal information).

The third limiting factor revealed by the research data shows financial difficulty in costing trips to other cities. “Radiostations, for example, need specific sponsorship for this purpose. As is not always the case, it also receives the content made available by the advisories of the clubs” (CHAVES JUNIOR, 2019, verbal information).

Given this scenario, it is evident the difficulty of journalists and broadcasters in observing, in a first, the possibility of diversifying the content beyond the coverage of remo and paysandu football. Moreover, inserting science into journalistic discourse is not unanimity. However, it is important to discuss sports science as an important element for the development of sports journalism with a scientific character.

All interviewees and interviewees agreed with the statement “science is present in sport”. From this finding, they exemplified the various forms that sports science manifests itself in the day-to-day. It is the impacts that sports activity has on the body, with advances in physiology that have helped develop training that result in better performance of players from training methods and games; the evolution of football studies not only in the execution of movements, speed, strength, but also in the mind. Another factor is in medicine, with the prevention of injuries and, as in the case of former player and commentator of Rádio Clube, Marquinho Belém, 43, diagnosis of diseases. Marquinho was a player at Clube do Remo, in 2004, had to suspend his career.

There was that tragedy of Serginho (30-year-old football player who had cardiorespiratory arrest playing a match in 2004), at São Caetano. After that, there was that medicine snap in doing the cardiogram echo. Before, i only did an electro and treadmill, the stress test. The echo is specific to the heart. Medicine came to prevent situations like Serginho did. I acquired obstructive asymmetric hypertrophic myocardiapathy because of overtraining, which could result in a cardiac arrest. The more I trained, the more my heart grew. Then, after recovered, I was able to play again (SOUZA, 2019, verbal information).

Another important point identified in the analysis of the interviews was the relationship between journalist and professional technical committees of the clubs, especially those of Remo and Paysandu. Journalists who follow little training and matches keep in touch by phone or rely on the intermediation of press relations. But who is often in the stadiums, has a closer relationship. Sector reporters, who exclusively accompany a club, are able to establish lasting relationships and, in some cases, friendship. However, most professionals keep in touch with the source within the routine of the deadline and the rules of the clubs, as Edson Carvalho states: “within a limitation of one’s own day-to-day, secrets that are not revealed. Often what they bring to our reality is something cutting-edge, innovative. They don’t want to publicize (sic), expose to everyone” (CARVALHO, 2019, verbal information).

Professionals from Pará also differ in relation to the public’s interest in science in sport. “Sometimes the fan doesn’t want to know much, wants to know if he is good ball, famous player or knows how to score. Supporter does not care much, so we avoid talking about this part” (FURTADO, 2019, verbal information). However, even if it is not interested, the reader / listener / viewer / fan need to have access, as Walmir Rodrigues says: “I don’t think he likes it. But he needs to understand a few things, understand what happens to certain players. It is that you need to understand when it matters” (RODRIGUES, 2019, verbal information). After all, “maybe he (the fan) is not aware of the dimension that can encompass science and sport, maybe he has no notion of this connection” (MALATO, 2019, verbal information).

THE SCIENCE OF SPORT

That injury to Pedro Carmona could raise several questions beyond the playing field: what was the mechanism of the injury? If it was really a sprain, was the player equipped with proper equipment? Did you perform any movement wrongly? Was the lawn ideal? Was there recklessness of Carmona or the opposing player? Was the refereeing permissive with violent plays? If it wasn’t a sprain, was there training overload in the week leading up to the match? Could the change in technical committee have contributed? Does the player have a history of chronic injuries? Can the sequence of games contribute to the injury?

Faced with a sports injury, the main focus is of interest is the time that the athlete will be away. Rarely is it questioned as to how and why the injury occurred or what could have been done for this injury to be avoided. First, it is of paramount importance to understand that an athlete’s injury cannot be a purely casual event (VILLARDI, 2004, p.174).

Medicine has contributions to this debate and to sports science. Inklaar (1994) deals with the importance of the etiology of soccer injuries and the different preventive programs to reduce the incidence and severity of injuries, taking into account intrinsic risk factors (joint flexibility, pathological ligament laxity and muscle stiffness, functional instability, previous injuries and inadequate rehabilitation) and extrinsic risk (exercise load in football, inadequate equipment, field conditions). For Villardi (2004), knee injuries caused by trauma are common in football. However, the implementation of preventive measures is not always simple. It is necessary to take into account the individuality of the athlete and the training load. But the group of athletes is heterogeneous, since they come from several states or countries. And more:

Preventive measures are not always easy to implement for a number of causes, and the binomial individuality of the athlete-load training is one of the main ones. In most football clubs, one can observe an extremely heterogeneous population of athletes. Individuals from different states or countries, with sports history, somatotypes, ages, cultural and sports habits, nutritional status or progress, are the most variable possible (VILLARDI, 2004, p. 172)

Understanding the causes of injuries in soccer is only one of the varied challenges that require interdisciplinary studies, since the modality involves physical, technical, tactical and psychological aspects. Sports science, since the 1980s, has presented studies that help identify and characterize particularities. From the studies of Guerra e Barros (2004), it is possible to find a wide conceptualization of football (Shepart & Leatt 1987; Ekblom, 1993; Zeederber, 1996; Reilly 1996, Valquer & Barros, 2004).

Some physical conclusions can help you better understand the training routine in clubs. Physically, a match requires multiple physiological demands from players (such as speed, strength, flexibility, and endurance). It was possible, for example, to draw a profile of the player. When it comes to height and weight, the average is 1.79cm and 76kg, respectively (Oberg 1984; Relly 1997; Shepard & Leatt 1987). It was also convinced that the many coaches usually repeat in sports coverage: training game situation. That is, training, such as speed, should follow the same characteristics of the activities performed during the match: 1) rarely the pikes are greater than 30 meters; 2) the great predominance is between 5 and 15 meters; 3) More than 95% of pikes are ballless; 4) the athlete starts the pike in the most different ways; 5) normally the pike ends with an action; 6) there is a tendency for the sides to perform longer pikes (20-30 meters) and the attackers, shorter (5-10 meters).

As is noticeable in sports news coverage, the trainings make up much of the content production. From the perception of speed training, it is possible to understand situations that happen in a match and guide a TV report or commentary in radio transmission, to exemplify. Can a newly arrived club full-back who has not had a speed training session show slowness during a match? What would be the cause? Tactical or physical disability?

Other important contributions come from biomechanics, the discipline derived from the natural sciences, which deals with physical analyses of biological systems, and consequently physical analyses of the movements of the human body as the kick pattern and the movements necessary for the player to perform the action (AMADIO & SERRÃO, 2004). Nutrition, along with player training and health, contributes to the best performance on the pitch. An example:

[…] it is necessary to consume carbohydrate immediately after the end of the game so that the replacement of muscle glycogen stocks is more efficient and fast within two hours, since in this period the enzymes responsible for muscle glycogen resynthesis are more active (GUERRA, 2004, p. 334).

The mind has also been receiving the attention of studies on the football field. Armando Nogueira wrote in Folha de São Paulo in 1999 that “not only legs live a great team”. For Ekblom (1995), only a few athletes achieve maximum perfection. “The stress resulting from physical and mental effort can contribute to blunt injuries and cause and aggravate relationship problems between team members and an internal imbalance team is a serious candidate for defeat and more stress” (BRANDÃO, 2004, p. 207).

In arbitration, studies on visual perception – from our field of vision, composed of the central photoindex (retinal region specialized in seeing details clearly) and peripheral vision (where some events around us may go unnoticed) – helped to understand the performance of assistant referees and reduce positioning errors (OLIVEIRA et al., 2004).

Verheijen et al. (1999) conducted studies with three renowned arbitrators and studies suggested that referees make decisions walking rather than being parked or running. They also emphasize that the best distance, for greater decision-making, should be maintained between the referee and the situations of the game in the range of 15 and 20 meters.

There are still studies on women’s football, in which it was concluded that it is not appropriate to compare men’s game and women’s game on equal bases. Everyone plays the same game, with the same rules, only the games are different (KIRKENDALL, 2004). Regarding the training of players in the basic categories, the educational function of the coach stands out, not only limiting him to the athlete’s orientation at times of training and competition, but in constant contact with the club, parents and those responsible for the development of the athlete’s personality (GOMES & ERICHSEN, 2004).

As is noticeable, the science of sport can explain various phenomena in football. But despite the progress of studies in this field, it is still necessary to understand why the dissemination of this scientific production is still restricted.

SCIENTIFIC CULTURE

The reflections of this work intend to contribute not only to communication, but also to scientific dissemination. How bueno (2010) distinguishes:

Scientific communication basically aims at the dissemination of specialized information among peers, in order to make known, in the scientific community, the advances obtained (research results, reports of experiences, etc.). in specific areas or the elaboration of new theories or refinement of existing ones. Scientific dissemination fulfills a primary function: to democratize access to scientific knowledge and to establish conditions for so-called scientific literacy. It therefore contributes to include citizens in the debate on specialized topics that can impact their life and work (BUENO, 2010, p.1).

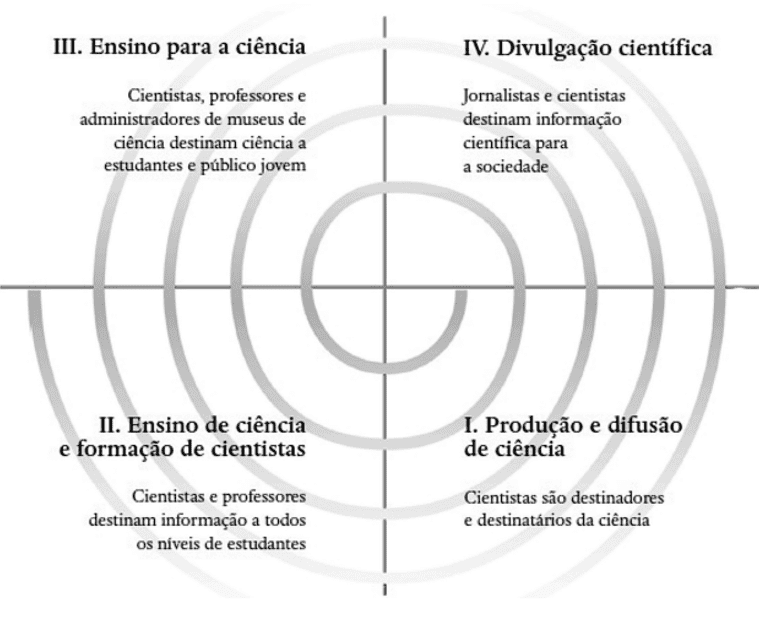

Both communication and scientific dissemination contribute, among other factors, to a particular type of culture that Vogt (2003) calls the spiral of scientific culture. This space can be represented by a spiral, accompanying the development of science through institutions focused on its practice and production, facilitating visualization and understanding, and defining what the author calls the Ibero-American space of knowledge.

Figure 1 – The spiral of scientific culture

Source: Vogt (2011, p. 10).

Thus, it is possible to observe, in the fourth IV, that journalists and scientists are the intended for scientific information for society, assuming a fundamental role in the interlocution of scientific culture and journalism. Also according to Vogt (2011), the ideal goal of the science disseminator is that scientific knowledge, as a cultural phenomenon can reach the level of treatment and experience of football – in which few are those who effectively play it, but there are many who understand it, know its rules, know how to play, are critical of its achievements, with it are moved and are passionate about it.

For this, in addition to talent, structural conditions of institutional support, such as resources, management plans, education and training programs, which are up to public policies to establish and make work, regularly and effectively, are necessary. The fact of not playing football does not prevent us from loving him, of being amateurs of his practice, of practicing it always, even if, most of the time, “only” by the aficionado admiration of supporter. (VOGT, 2011, p 13).

JOURNALISM

SPECIALIZED JOURNALISM

For Tavares (2007, p. 42), journalism is a social practice focused on “storytelling”, where, in the records, are the testimony or investigation, construction or reconstruction of an event, or knowledge. “The journalist captures the world, conforms it and informs it through a saying. It is said about the world, for it and often for it.”

In this way, journalism is the result, as Traquina (2001) says, of processes of social interaction between journalists, between journalists and society, and between journalists and their sources of information. This interaction, very often, is realized in a discursive unit of the journalistic system: the news, a discursive meta-event (RODRIGUES, 1993), which reports another event, but not any event, but a remarkable, singular and concrete event that breaks with the organization of a reality.

Sousa (2002, p. 13), journalism is nothing more than “linguistic artifacts that seek to represent certain aspects of reality and result from a production and manufacturing process where several factors interact, among others.” There is also a more direct conceptualization:

Journalism is journalism, be it sports, political, economic, social. It can be propagated in television, radio, newspaper, magazine or internet. It doesn’t matter. The essence does not change because its nature is unique and is closely linked to the rules of ethics and the public interest (BARBER; RANGEL, 2006, p. 13).

However, there is a category of journalism, specialized journalism, which reveals certain “invisible events” from the mediation process.

Mediation, in this sense, is presented as a media practice of capturing reality and transmitting it from a production process of its own, without running away from the idea of communicative interaction that surrounds it. Thus, we perceive mediation as a socially contextualized process, inserted in a broader communicative logic, which encompasses several areas of production, reception and relationship between both (TAVARES, 2007, p.12).

In this sense, can scientific and sports journalism mediate “invisible events” produced by sports science and public interest? It is important to reflect on sports and scientific journalism.

SCIENTIFIC JOURNALISM

Bueno (2009) recalls that the history of the Brazilian press coincides with the beginnings of scientific journalism, such as Hipólito da Costa, founder of Correio Brasiliense, who maintained close contact with scientists and produced reports and news in the fields of botany, agriculture and medicine, in addition to the periodicals “O Fazendeiro” and “Chácaras e Quintais”.

Scientific journalism, over these little more than 200 years of existence in Brazil, according to Bueno (2012), has evolved a lot, but, if it has gained great and visibility, it has accumulated new challenges that need to be promptly faced, not only from a better technical training, but with critical spirit and courage. Thus:

Scientific journalism concerns the process of circulation of science, innovation and technology (CI&T) information formatted to serve an unqualified audience, that is, the lay public. It has some unique characteristics: this information is, primarily, conveyed by the mass media and obeys the journalistic production system, that is, make up the so-called journalistic discourse. Thus, he distinguishes himself from both scientific communication and scientific dissemination in its broadest sense, defining himself as one of his individuals (BUENO, 2012, p. 2).

Vera Lúcia Salles (1981) understands that scientific journalism is the information conveyed by the mass media and transmitted in language accessible to the general public.

As Bueno (2009) points out, scientific illiteracy, a consequence of the precariousness of formal science education in Brazil, keeps the “large public” far from scientific journalism, which added to the little sensitivity of editors and communication companies, result in the idea that Science, Technology and Innovation do not interest the ordinary citizen. Except in some spectacular cases, assuming a sensationalist narrative, contributing even more to misinformation.

SPORTS JOURNALISM

Sports journalism, perhaps in the conception that is today, was “invented”, according to Capraro (2011), by the Carioca Mario Rodrigues Filho, still 23 years old, when he founded, in 1931, one of the first (short-lived) sports newspapers, “the World of Sports”. Five years later, along with financial help, including Roberto Marinho’s, he became the owner of jornal dos Sports. Biographers by Mario Rodrigues Filho evidence it as one of the main references for the break with the old journalistic model that dealt with sports, characterized by long-fetched writing, frivolous content and analysis from an elitist perspective (CASTRO, 1992 apud CAPRARO, 2011).

Although he was one of the first chroniclers dedicated exclusively to football, becoming as popular as the players of the time, in addition to the popularization of football demanding changes in the way the sport was reported, the most engaged in extoling the professional virtues of Mario Filho was his own brother, Nelson Rodrigues, already consecrated theologian and writer:

Friends, each generation should have a Mario Filho, that is, a man of great homeric evocation. And then, here’s what would happen wonderfully: – the story of one generation would pass on to another generation, just as the call of the círio passes to another cyrio. But Mario Filho died and we no longer heard the great corners of football (RODRIGUES, 1994, p. 174).

Even before Mário Filho became the father of “modern” sports journalism, other professionals already dedicated to the coverage of sporting events. André Ribeiro (2007) considers “The Athlete”, first published in 1891, as a landmark of sports journalism in São Paulo and Brazil. Other São Paulo periodicals were also emerging (such as “O Sport”, “O Sportsman”, “A Pátria Esportiva”) decades later. However, the sports that gained prominence in magazines and newspapers were cycling, rowing and peat.

The press of the time did not prioritize football. After all, the capital of São Paulo lived intense process of urbanization and economic growth, attracting immigrants to work in industry and infrastructure works. Football was still practiced as a leisure, including by foreigners.

Scoring soccer-related agendas in that scenario of São Paulo was very difficult. But turning a blind eye to the growth of football in the floodplains seemed a serious error of evaluation of those responsible for the main newspapers of the time. However, as the elite also prevailed in the newsrooms, the creation of the first Paulista Football League, at the end of 1901, with only five elite clubs, became news (RIBEIRO, 2007, p. 23).

In Rio de Janeiro, according to Oliveira (2013), the scenario was similar to that of the state capital. Until the beginning of the 21st century, there were only two teams (Paysandu Cricket Club and Rio Cricket and Atlhetic Association) that won the local press coverage, still little interest to the main newspapers of the time to disseminate news about football in the then capital of Rio.

What he called the journalists was the fact that a match ended without winners, as recorded in a small note from the Morning Mail in the first game of foot-ball “showed the disappointment of the reporter with the result of the match, which ended tied at 1-1″. Accustomed to the coverage of competitions such as rowing and peat, which always had a winner, the way was to write that the score was undecided (RIBEIRO, 2007).

The current coverage of sports journalism, according to Bueno (2005), is focused on the sport of competition. Working with sports journalism has its specificities and is often confused with pure entertainment. Moreover, from an attentive eye, it is revealed an almost exclusive concern with football, resulting in a disproportionate space (and time) in the media despite the number of practitioners of the various sports activities (BARBER AND RANGEL, 2006).

The media only contemplates certain sports in major international events, such as the Pan American Games and the Olympics, and yet highlights winners (the medalists), relegating the best to oblivion, failing to fulfill its role of stimulating new vocations and valuing the spirit of competition (BUENO, 2005, p. 21).

In addition, Bueno (2005) believes that coverage is limited to a limited space of action – pre, during and post-departure – resulting in poor agendas, addressing gossip and intrigue, even if there are relevant topics to be addressed. The author also highlights a ready third: the sports press suffers from a chronic myopia, exhibiting prejudice against clubs and sports of lesser expression, forgotten that our main values were revealed far from the major centers. Not to mention the concern with journalists who seek to favor in comments or broadcasts the teams of greater fans, if not major centers. The fifth point, related to the quality of journalistic information, associated with sports coverage in Brazil. According to Bueno:

It is not uncommon to find wrong match results, title matters as opposed to comments and news, misinformation about top scorers, which is absolutely common, ignorance sore tournament regulations and about the position of clubs in the tables. In this case, there are surrealist comments about situations that will never materialize because they rely on false data. It improvises a lot in this area, which is risky because, in most cases, due to the interest of fans, this information is well known, which only increases the lack of credibility of those who cover Brazilian sport (BUENO, 2005, p. 24).

The scenario is favorable for different results. According to Maluly (2005), in sports journalism, the fact always comes before (local and the competition are already previously scheduled) and the players have been, for the most part, cast. That is: the reporter ends up depending only on the unfolding of the facts. And this can be extended to workouts, biographies, preparations and news outcomes. After all, in sports journalism, everything that involves the fact is important to hold the attention of the public, depending on the quantity and quality of the information that is transmitted.

In any dispute the report can be done in a pleasant and interesting way, if the experienced reporter takes notice in advance of the teams, inform if and arrive at the site an hour before for the final check. If you wait until the competition begins to obtain this information, the result of your work may become uninteresting (HOHENBERG, 1981, p.391, apud MALULY, 2005, p. 47).

Also according to Maluly (2005), the Internet facilitates access to data before difficult access. However, he points out that the matter based only on the use of new media is dangerous, because, not always, the information placed on the Internet is reliable. Electronic means serve as an aid tool in the search for information. The journalist, in this case, in the role of researcher, needs to observe the dissecting source or even with other sources, be it human or bibliographic, if the data is valid.

It is evident that, in this context, scientific publications (articles, books, theses and dissertations) are recognized as reliable sources for the production of a subject. But the author warns of what he calls “scientific and technological speculation.” Novelty or novelty brought to journalism a distrust of what is disclosed, “since the mass media could be used as disseminators of dubious promises or false experiences, and not as disseminators of science and technology” (MALULY, 2005, p. 49). The journalist needs to detach himself from this and make use of data research and productions already scientifically proven so as not to fall into the error of producing a more advertising than journalistic article.

Thus, sports journalism approaches a real scenario of competitions, with characters constructed through facts (and not fictional), and opens windows for questions more aligned with the reality lived by the athlete. Another way to produce the report is the technical committee, the athlete’s or the team’s support team, which can provide accurate information (MALULY, 2005). In addition, the tactic of the technical committee for a competition, such as the lineup, the means of preparation (feeding, concentration, altitude etc.). and information about other athletes are factors that influence the outcome and can contribute to journalistic coverage.

There is no denying that one of the concerns of journalists is to choose a professional who is an expert on the subject, not just a friend or colleague. “The specialists are professionals from the most varied areas of knowledge (human, exact and biological), and their testimonies are used to clarify a certain subject that is not clear to the journalist” (MALULY, 2005, p. 57). Thus, all people directly or indirectly involved in the sport are sources of information for the reporter in sports coverage. However, as Bueno (2005, p. 15) notes, sport cannot be seen as an “activity immune to economic, social, cultural and political interests. This causes decontextualization that hinders some understandings of what occurs in the modality.”

This critical attitude towards the situation of sport in Brazil and the dissemination of sport as a cultural element for leisure and health, among other values, can contribute to the improvement of the quality of life of Brazilians (MALULY, 2005, p. 59).

SPORTS-SCIENTIFIC JOURNALISM

According to the studies of Messa (2005, p. 3), starting from the history of Brazilian sports journalism, it is observed that it is mere entertainment and has 80% of the news themes and specialized reports revolved around a single sport that is football. From this, the author launches a question: “could we conceive a sports journalism that was not restricted only to the entertainment of the reader-fan audience?”

Following the critical analysis of Messa (2005), sports coverage does not prioritize what is essential for the public: “daily sports journalism is, in reality, a journalism of variety amenities, whose theme is not the sport itself, but its conglomerates and attackers (characters) that make up this market network” (MESSA, 2005, p. 3).

This corroborates what Alsina (2009) characterizes as the mass culture, structured in the logic of meeting market demands. The entertainment market determines a limited number of (though many) products and content-standardized products, which are seen in series of cyclical returns of the same product and in the imitation of several others. And the public is conditioned in their tastes by the abstract, “what characterizes mass culture is standardization and repetition (ALSINA, 2009, p.198).

For this reason, Ivanissevich (2005) makes some weightings when it comes to popularizing science through the media. According to the author, there is resistance from the scientific community. As the media is a business with a producer selling, in this case the information, entrepreneurs, who are not necessarily journalists, aim to achieve the highest possible profit margin in record time.

The success of sales or the achievement of several points in Ibope depends, among other factors, on what type of information is transmitted and how it is presented to the public. Thus, what will determine what news will be transmitted is certainly not the will of the scientist in disclosing his results, but what the editor of TV, radio, magazine or newspaper and sometimes what the manager of the commercial sector – consider of greatest interest to increase the sale of his product (IVANISSEVICH, 2005, p. 14).

However, the author recognizes that isolated attempts to disseminate scientific knowledge (through conventional classes, plays, films, exhibitions, lectures) have little impact on the population. But if science is conveyed in the media it can reach millions of people in a single day and “it would be useless to ignore an instrument with this power of reach scientists and educators should consider it an ally – always attentive to its vice- in its attempt to disseminate science” (IVANISSEVICH, 2005, p. 28).

The language of articles or programs published by the media is a determining factor for the success or failure of the transmission of information. Journalists – communication experts – are expected to choose, select, interpret, summarize and translate information to the public. To reach the population, news about science must pass, like those of any other area, through this process. The difficulties of interpretation and editing can be added to the variable time. Of course, it has different meanings for journalists and scientists. Scientists hardly understand the seemingly careless rush of journalists. These, especially those who work in news, suffer from the ironically named “beautiful of death” (deadline) (IVANISSEVICH, 2005, p.18).

In this context, journalist coverage is restricted, according to Messa (2005), to the identification of a journalistic hole, usually to scandalize, produce ephemeral and expendable material, summarizing the construction of images of athletes, brands, sponsorship, images of the fans. Despite this:

I propose a sports journalism of a scientific nature. I do not want, in essence, to express a repudiation of factual sports journalism, now it would be too late to purge it. On the contrary, I already assume that there is this practically irreversible trend, because the reading public has already been trained for this. It would be like letting him down from his passionate expectations. What is intended is to try to awaken other or new angles of interest to the reader/ spectator, in order to meet the demand of knowledge about sports. The proposal of sports-scientific journalism is only reason to be due to this conjuncture (MESSA, 2005, p. 4).

But, of course, within the logic of mass culture, Ivanissevich (2005) stresses that there needs to be an alignment of interests between scientific dissemination and media. Even if the role of the media is to sell information, it is possible that the good journalist knows how to choose topics of interest and transmit them correctly and attractively, using certain resources, increasing the quality of the product with credibility.

To be conveyed by the media, science must be able to arouse interest, maintain the attention of the reader, listener or viewer until the end of the article or program, and be well understood by the general public (IVANISSEVICH, 2005, p. 21).

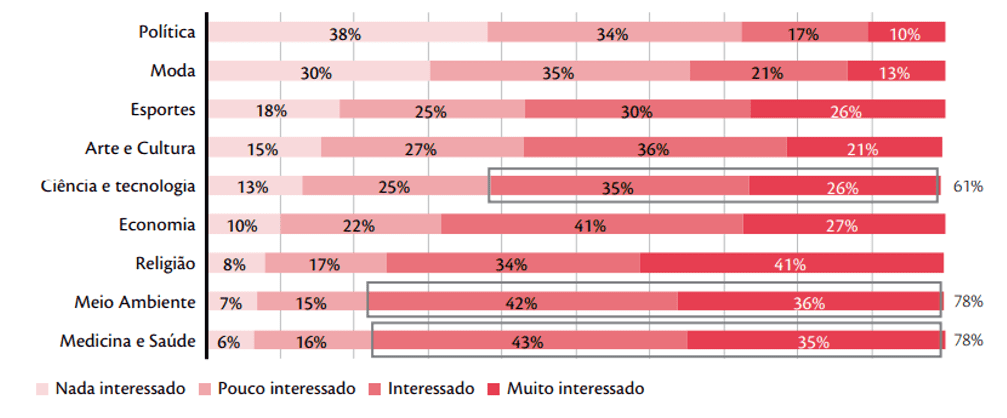

In this sense, it is important to analyze the latest edition of the Research on Public Perception of Science and Technology (C&T) in Brazil, of the Center for Management and Strategic Studies (CGEE) which, in 2015, heard 1,962 young people and adults over the age of 16, in all regions of the country, among several aspects, the interest of Brazilians in C&T.

The research concluded that it is a high rate of interest declared by the population by science and technology as a whole or by specific topics involving scientific and technological knowledge, including approaches to medicine and health or the environment.

It is also high interest Brazilians reveal to have, specifically, science and technology, since the majority of the population (61%) declares yourself interested (35%) or very interested (26%). In addition, what the interviewees express to have for sport or art and culture. (CGEE, 2015), as shown below.

Figure 2: Percentage of respondents according to the stated interest in science and technology and other topics, 2015.

Thus, interest in Science & Technology leads to a fertile path for Scientific Literacy (DURANT, 2005) that designates what the general public should know about science. Ivanissevich (2005) argues that it is myth the public’s disinterest in science and needs to be overturned and that it is possible to rely on a quality scientific dissemination can be made. And yet: “more than a literacy in science, the public needs good interpreters” (IVANISSEVICH, 2005, p. 28-29).

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

Messa (2005) and Bueno (2005) made harsh criticisms of sports coverage. He also believes that he lacks competence for the media to deal with specialized issues, such as doping and sports lions, simply because the coverage does not assume investigative or research character, content with superficial sources and statements. According to the author, “there is no time and no space for breath-taking matters, because journalism lives only in function of tournaments and matches” (BUENO, 2005, p. 21).

You have to go beyond the hook. The first step is to understand that sport, especially football, cannot be treated in isolation, not observing the context in which it is inserted. From the reflections of this work, it was possible to perceive the science of sport assuming a fundamental role in this sense. Studies in medicine, physiology, biomechanics, nutrition, psychology, among others, have contributed decisively to the development of players, teams and competitions. When approaching scientific journalism, sports journalism incorporates some particularities that can result in a fruitful relationship, as Messa (2005) argues, in the proposition of scientific-sports journalism.

In Pará, the technical committees of Remo and Paysandu have bet on increasingly qualified professionals with academic trajectory. And, to what has been put, may be the crack for journalists and broadcasters not only faced the factors that limit sports coverage, but also ensure the diversity of content delivered to the viewer, listener or reader – which proved, from research, interested much more in science and technology than the sport itself, contrary to common sense – and contributing to the development of scientific culture , since scientists and journalists are protagonists in the dissemination of knowledge produced by science to society (VOGT, 2011).

It would be the balance between sports journalism and opportunity, after all, as Barbaeiro & Rangel (2006) affirms, the essence of journalism is unique and is linked to the rules of ethics and the public interest. From the analysis of the interviews of professionals from Pará, a favorable scenario is identified in an important aspect: training. Of the 16 interviewees and interviewees, 14 reached higher education. Although it is possible to observe more experienced professionals seeking training in areas other than communication, a considerable amount of sampling, especially those who entered the market about 10 years ago, has training in journalism. Although one of the four higher education institutions that offer a face-to-face journalism course in Pará has the discipline of sports journalism in the curricular component, the scenario is favorable. And at the same time urgent.

Sports coverage has been recognized since the days of Mario Filho for its accessible language and ease of storytelling. However, he needs to be aware of what Bueno warned about the risks of improvisations, which result in errors and surrealist comments about impossible situations. In parallel to this, the interest of fans and the availability of other forms of access to information only contribute to the lack of credibility of those who charge the sport in Brazil (BUENO, 2005).

Thus, sports journalism can also be an ally in scientific literacy. But not just that. As Maluly (2005) stated, dissemination as a cultural element for leisure and health, and why not science, can contribute to the improvement of life in Pará, from Brazil. Go too much acorn of the hook.

REFERENCES

Alsina, R. M. A construção da notícia. Petrópolis, RJ: Vozes. 2009.

Amadio, A.; Serrão, J. C. A biomecânica e seus métodos para análise de movimentos aplcados ao futebol. In: I. Guerra, & T. Barros, Ciência do Futebol (p. 338). Barueri, SP: Manole. 2004.

Andrade, P. Muito além da fisgada: a ciência e o esporte na cobertura jornalística no Pará. (A. L. Sousa, Entrevistador) (29 de Janeiro de 2019).

Barbeiro, H.; Rangel, P. Manual do Jornalismo Esportivo. São Paulo: Contexto. 2006.

Boni, V.;Quaresma, S. Aprendendo a entrevistar: como fazer entrevistas em Ciências. Revista Eletrônica dos Pós-Graduandos em Sociologia Política, 68-80. 2005.

Brandão, M. F. O lado mental do futebol. In: I. Guerra, & T. Barros, Ciência do Futebol (p. 338). Barueri, SP: Manole. 2004.

Bueno, W. d. Chutando Prá Fora: os equívocos do jornalismo esportivo brasileiro. In: J. C. Marques, S. Carvalho, & V. T. Camargo, Comunicação e Esporte – Tendências (p. 2016). Santa Maria: Palloti. 2005.

Bueno, W. d. Jornalismo Científico: revisando o conceito. In: G. Caldas, & S. Bortoliero, Difusão e Cultura Científica: alguns recortes (pp. 157-178). Salvador: EDUFBA. 2009.

Bueno, W. d. O Jornalismo Científico no Brasil: os desafios de uma longa trajetória. In: C. d. Porto, Difusão e Cultura Científica (pp. 113-125). Salvador: EDUFBA. 2009.

Bueno, W. d. As fontes comprometidas no jornalismo científico. In: C. D. Porto, A. M. Botas, & S. Bortolieiro, Diálogos entre Ciência e Divulgação Científica: Leituras Contemporâneas (p. 240). Salvador: EDUFBA. 2011.

Capraro, A. M. Mario Filho e a “Invenção” do Jornalismo Esportivo Profissional. Movimento, 17(2), 213-224. 2011.

Carvalho, E. Muito além da fisgada: a ciência e o esporte na cobertura jornalística no Pará. (A. L. Sousa, Entrevistador) (28 de Janeiro de 2019).

Centro de Gestão e Estudos Estratégicos. A ciência e a tecnologia: percepção pública da C&T. Brasília, DF: Centro de Gestão e Estudos Estratégicos. 2017.

Chaliê, L. Muito além da fisgada: a ciência e o esporte na cobertura jornalística no Pará. (A. L. Sousa, Entrevistador) (26 de Janeiro de 2019).

Dejavite, F. A. A notícia light e o jornalismo de infotenimento. XXX Congresso Brasileiro de Ciências da Comunicação. Santos, SP: Intercom. 2007.

Dias, B. Muito além da fisgada: a ciência e o esporte na cobertura jornalística no Pará. (A. L. Sousa, Entrevistador) (29 de Janeiro de 2019).

Fernandes, M. Muito além da fisgada: a ciência e o esporte na cobertura jornalística no Pará. (A. L. Sousa, Entrevistador) (27 de Janeiro de 2019).

Ferreira, C. Muito além da fisgada: a ciência e o esporte na cobertura jornalística no Pará. (A. L. Sousa, Entrevistador) (26 de Janeiro de 2019).

Furtado, A. Muito além da fisgada: a ciência e o esporte na cobertura jornalística no Pará. (A. L. Sousa, Entrevistador) (27 de Janeiro de 2019).

Futebol, C. B. Regulamento Geral das Competições – 2019. Acesso em 14 de Janeiro de 2019, disponível em CBF: https://conteudo.cbf.com.br/cdn/201812/20181211073907_874.pdf (10 de Dezembro de 2018).

Globo Esporte Pará. Sem Pedro Carmona, Paysandu se reapresenta após goleada no Parazão. Acesso em 15 de Novembro de 2018, disponível em Globo Esporte Pará: https://globoesporte.globo.com/pa/futebol/times/paysandu/noticia/sem-pedro-carmona-paysandu-se-reapresenta-apos-goleada-no-parazao.ghtml (26 de Feveveiro de 2018).

Gobbi, M. Mário Gobbi volta atrás e diz que futebol não é business. (U. Esportes, Entrevistador) (27 de Maio de 2013).

Gomes, A.; Erichsen, O. A. A preparação do futebolista na infância e adolescência. In: I. Guerra, & T. Barros, Ciência do Futebol (p. 338). Barueri, SP: Manole. 2004.

Guerra, I. Nutrição no Futebol. In: I. Guerra, & T. Barros, Ciência do Futebol (p. 338). Barueri, SP: Manole. 2004.

Guerra, I.;Barros, T. Demandas fisiológicas do futebol. In: I. Guerra, & T. Barros, Ciência do Futebol (p. 338). Barueri, SP: Manole. 2004.

Guerreiro, G. Muito além da fisgada: a ciência e o esporte na cobertura jornalística no Pará. (A. L. Sousa, Entrevistador) (28 de Janeiro de 2019).

Haguette, T. M. Metodologias Qualitativas na Sociologia . Petrópolis: Vozes. 1992.

Inklaar, H. Soccer Injuries – II: Aetiology and Prevention. Sports Medicine, 81-93. 1994.

Ivanissevich, A. A mídia como intérprete. In: S. Vilas Boas, Formação & Informação Científica (pp. 13-30). São Paulo, SP: Summus. 2005.

Júnior, A. C. Muito além da fisgada: a ciência e o esporte na cobertura jornalística no Pará. (A. L. Sousa, Entrevistador) (27 de Janeiro de 2019).

Júnior, M. D. Muito além da fisgada: a ciência e o esporte na cobertura jornalística no Pará. (A. L. Sousa, Entrevistador) (27 de Janeiro de 2019).

Kirkendall, D. O futebol feminino. In: I. Guerra, & T. Barros, Ciência do Futebol (p. 338). Barueri, SP: Manole. 2004.

Lakatos, E.;Marconi, M. d. Técnicas de Pesquisa. São Paulo, SP: Atlas. 1996.

Luz, G.; Castilho, M.; Vieira, C. N. O futebol brasileiro no contexto do período militar (1964 – 1979). Revista Observatorio de la Economía Latinoamericana, 17. 2017.

Malato, M. Muito além da fisgada: a ciência e o esporte na cobertura jornalística no Pará. (A. L. Sousa, Entrevistador) (26 de Janeiro de 2019).

Maluly, L. O jornalismo esportivo e as técnicas de reportagem. In: J. C. Marques, S. Carvalho, & V. R. Camargo, Comunicação e Esporte – Tendências (p. 216). Santa Maria: Pallotti. 2005.

Messa, F. d. Mario Filho e a “Invenção” do Jornalismo Esportivo Profissional. Anais do 8o Fórum Nacional de Professores de Jornalismo, 1-8. 2005.

Mielniczuck, L. Jornalismo na web: uma contribuição para o estudo do formato da notícia na escrita. Salvador, Bahia: Universidade Federal da Bahia. (Março de 2003).

Neto, R. M. Encontro Globo e Afiliadas – Esporte. Palestra: integração no esporte do Grupo Globo. São Paulo, São Paulo. (29 de Agosto de 2018).

Oliveira, M. Os componentes físicos e técnicos necessários ao melhor desempenho do árbitro de futebol. In: I. Guerra, & T. Barros, Ciência do Futebol (p. 338). Barueri, SP: Manole. 2004.

Oliveira, R. Jornalismo Esportivo/Entretenimento: a construção identitária das edições carioca e paulista do Globo Esporte. Juiz de Fora, MG, Minas Gerais: Universidade Federal de Juiz de Fora. 2013.

Oliveira, R. Uma nova geração de jornalistas esportivos se dedica a pôr mais ciência no futebol brasileiro. Acesso em 31 de Janeiro de 2018, disponível em Época: https://epoca.globo.com/esporte/noticia/2018/01/uma-nova-geracao-de-jornalistas-esportivos-se-dedica-por-mais-ciencia-no-futebol-brasileiro.html (31 de Janeiro de 2018).

Penna, G. Dado afasta clima de euforia no Paysandu e revela preocupação com Carmona. Acesso em 30 de Novembro de 2018, disponível em Globo Esporte Pará: https://globoesporte.globo.com/pa/futebol/times/paysandu/noticia/dado-afasta-clima-de-euforia-no-paysandu-e-revela-preocupacao-com-carmona.ghtml (25 de Fevereiro de 2018).

Rodrigues, A. D. O Acontecimento. In: N. Traquina, Jornalismo: questões, teorias e “estórias” (pp. 27-33). Lisboa: Vega. 1993.

Rodrigues, N. O Baú de Nelson Rodrigues. São Paulo, SP: Companhia de Letras. 2004.

Rodrigues, V. Muito além da fisgada: a ciência e o esporte na cobertura jornalística no Pará. (A. L. Sousa, Entrevistador) (28 de Janeiro de 2019).

Roseguini, G. Laboratório do GE explica diferenças de massa muscular nos atletas. Acesso em 02 de Janeiro de 2019, disponível em Globoplay: https://globoplay.globo.com/v/3981972/ (15 de Fevereiro de 2015).

Santo, A. E. Muito além da fisgada: a ciência e o esporte na cobertura jornalística no Pará. (A. L. Sousa, Entrevistador) (27 de Janeiro de 2019).

Santos, V. L. João Ribeiro como jornalista científico no Brasil: 1895-1984. São Paulo, SP: Universidade de São Paulo. 1981.

Silva, P. e. A importância do limiar anaeróbico e do consumo máximo de oxigênio em jogadores de futebol. Revista Brasileira de Medicina Esportiva, 225-232. 1999.

Sousa, J. P. Teorias da notícia e do jornalismo. Chapecó, SC: Argos. 2002.

Sousa, M. Muito além da fisgada: a ciência e o esporte na cobertura jornalística no Pará. (A. L. Sousa, Entrevistador) (26 de Janeiro de 2019).

Souza, D. A. As origens de “O futebol é o ópio do povo”. Acesso em 20 de dezembro de 2018, disponível em Ludopédio: https://www.ludopedio.com.br/arquibancada/as-origens-de-o-futebol-e-o-opio-do-povo/ (25 de Junho de 2018).

Souza, M. “. Muito além da fisgada: a ciência e o esporte na cobertura jornalística no Pará. (A. L. Souza, Entrevistador) (27 de Janeiro de 2019).

Tavares, F. d. O Jornalismo Especializado e a mediação de um ethos na sociedade contemporânea. Em Questão, 13, pp. 41 – 56. (jan/jun de 2007).

Traquina, N. O Estudo do jornalismo no século. São Leopoldo: Editora da Universidade do Vale do Rio. 2001.

Triviño, A. N. Introdução à Pesquisa em Ciências Sociais. São Paulo, SP: Atlas. 1997.

Valor Econômico. Futebol enfrenta bem tempo de crise na economia. Acesso em 20 de Dezembro de 2018, disponível em Valor Econômico: https://www.valor.com.br/empresas/5558479/futebol-enfrenta-bem-tempo-de-crise-na-economia (01 de Junho de 2018).

Valquer, W.; Barros, T. Preparação física no futebol. In: I. Guerra, & B. Turibio, Ciência do Futebol (p. 338). Barueri, SP: Manole. 2004.

Villardi, A. As lesões no futebol. In: I. Guerra, & T. Barros, Ciência do Futebol (p. 338). Barueri, SP: Manole. 2004.

Vogt, C. A Espiral da Cultura Cientifica. Acesso em Dezembro de 2018, disponível em ComCiência: http://www.comciencia.br/reportagens/cultura/cultura01.shtml (Julho de 2003).

Vogt, C. De Ciências, Divulgação, Futebol e Bem-Estar Cultural. In: C. D. Porto, A. P. Brotas, & S. Bortoliero, Diálogos entre Ciência e Divulgação Científica: Leituras Contemporâneas (p. 240). Salvador: EDUFBA. 2011.

[1] Graduated in Social Communication, with qualification in Journalism, from the University of the Amazon (UNAMA); Specialist in Scientific Communication in the Amazon (FIPAM/NAEA), by the Federal University of Pará (UFPA); Master’s degree in Development Planning, in the Graduate Program in Sustainable Development of the Humid Tropic (PPGDSTU/NAEA), by UFPA.

[2] Professor at the Faculty of Communication of UFPA; Master’s degree in Contemporary Communication and Culture from the Federal University of Bahia; PhD in Information Sciences and Media Studies, Fernando Pessoa University, Porto-Portugal.

[3] Theologian. PhD in Clinical Psychoanalysis. Researcher at the Center for Research and Advanced Studies, São Paulo, SP.

[4] Professor of the Graduate Program in Anthropic Studies in the Amazon (PPGEAA/UFPA). PhD in Medicine/Tropical Diseases. Professor and Researcher at the Federal University of Pará (UFPA). Researcher at the Center for Tropical Medicine (NMT/UFPA), Belém (PA), Brazil.

[5] Professor of the Graduate Program in Sustainable Development of the Humid Tropic (PPGDSTU), of the Center for High Amazonian Studies (NAEA), of the Federal University of Pará (UFPA); Master in Physical Education, from the Metodist University of Piracicaba (UNIMEP); PhD in Sciences: Socioenvironmental Development, Federal University of Pará (UFPA).

Sent: March, 2020.

Approved: March, 2020.