ORIGINAL ARTICLE

GODOY, Juliano Bernardino de [1], ASSIS, Rogério de [2]

GODOY, Juliano Bernardino de. ASSIS, Rogério de. Between the cross and the sword: Historical panorama of Liberation Theology in Latin America. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar Núcleo do Conhecimento. Year 05, Ed. 05, Vol. 08, pp. 05-16. May 2020. ISSN: 2448-0959, Access link: https://www.nucleodoconhecimento.com.br/theology-en/cross-and-the-sword

SUMMARY

This article approaches liberation theology from the perspective of Latin America in order to trace a brief historical panorama, its theological and theoretical foundation, its peak moment and its cooling. Moreover, it is intended to show that such a movement is not, under any circumstances, a monopoly of the Roman Catholic Church, as many by pure ignorance think it is. It will be shown that such a theological movement has done and is still part of the Protestant world, more timidly, it is quite true, but it is true that many Protestants and evangelicals have embraced the cause in the same way. Finally, according to the experts referenced, liberation theology has not yet died, remains alive, even if imperceptibly in the postmodern days. Thinking about such issues, given their timeliness, justifies the relevance of this reflection.

Keywords: Liberation Theology, Latin America, Christology, sociology of religion.

1. INTRODUCTION

In a brief way, we will present the theme of Liberation Theology in the context of Latin America in order to arouse the greatest interest of the reader to deepen the theme. To this end, we chose to go the following methodological path: 1- Origin and what is and Liberation Theology; 2- Theoretical and theological assumptions of Liberation Theology; 3- Decay and future of Liberation Theology; followed by final considerations and appropriate references. With faith and hope that the subject will be deepened from the seed launched in this article, we, the authors, wish you a good reading and a good benefit. Gratitude for her interest in the subject, after all, in our opinion, of theologians, pastors, scholars and eternal apprentices, all theology is liberating, for it promotes an encounter with God, and in turn every encounter with God is an encounter of liberation.

2. ORIGIN AND WHAT IS LIBERATION THEOLOGY

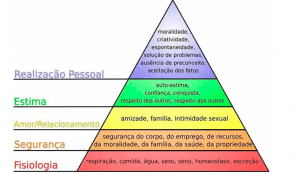

The “Liberation Theology”, or, in Spanish, “Teologia de la Liberación“, is a theology that was born and constructed from a critical analysis of social reality. With the phytous look on the impoverished face of Christ the Good Shepherd, instead of the phytous gaze on the face of Christ Pantocrator[3], it brings a great difference of look and theological point of view. Unlike traditional theology, which is part of contemplation of realities, let us say “heavenly”, Liberation Theology is made from earthly realities, especially from the cruel question of poverty and misery. It is, therefore, a theology made by people of flesh and blood, with their feet on the ground. The term Liberation Theology was created by the Peruvian priest Gustavo Gutierrez[4], considered the “father” of this modality of thinking and theological action. Liberation Theology was formulated from a movement within the Latin American Catholic Church around the 1950s-60s.

In this decade, great events have shaken society and the Church and in the wake of these events has aroused the need for the Church’s involvement in the social issue. Reading reality from a rereading of the Gospel that justified the engagement of Christians in social problems and facing the problems of hunger, violence, city and land administration were some of the proposed reflections. According to Rodrigo Augusto Leais Camilo, a scholar of Liberation Theology, during the 20th century, within the Catholic Church, the concern with the social issue deserved a special attention in Brazil and Latin America, due to history and the great Catholic presence in this region. In Brazil, since Catholicism ceased to be the official religion of the State, with the Proclamation of the Republic in 1889, the Church has undergone major transformations.

According to Rodrigo Augusto, messianic movements, the lack of priests and the growth of other beliefs contributed to the reorganization of the structure of the Catholic Church in Brazil. In this context, christians also grew to be involved in the daily lives of other faithful, providing a direct context with the suffering and difficulties of a large portion of the population. It was in this context of the Church attentive to the issues of poverty and oppression that the liberation theology movement was born. Add to all this the emergence of military dictatorships in Latin America. Liberation Theology has expanded and gained presence on all continents as a different model of making theology from the social reality of the poor.

According to Leonardo Boff: “the poor were convicted because they committed an unacceptable crime: supporting those who are out of the market and zero economic” (BOFF, 2011, p. 12). The Catholic hierarchy condemned her for falling into a practical “heresy” by claiming that the poor can be a builder of a new society and a new model of the Church. Naturally and unfortunately, many were the men and women religious silenced by the Catholic dome, among them Leonardo Boff himself, at the time of the Franciscan friar. However, to the surprise of many, not only has the Catholic Church silenced its own, but other historical Churches have done so, as can be read in this brief quote from João Dias de Araújo in relation to the Presbyterian Church.

This coup against the young Presbyterian press was a reaction to the bold and true statements that culminated in the June 1960 issue. To give only one example of this issue: the young Paul Wright writes the article ‘O Senhor do Mundo’, in which he dealt with Christ’s action in the Church and in the world and the consequent freedom for the Christian to witness. At the end of the article he declared: ‘The problem is no longer whether dancing or not dancing, whether smoking or not smoking is a sin, for being Jesus our Lord, these things no longer have power over us’ (Youth, June 1960). This and other statements have shaken the foundations of the church’s old emphasis on moralistic preaching. They could not be read by believers of a century of ecclesiastical life (Araújo, 2002, 40).

Since the 1960s, a growing awareness of the real producing mechanisms of underdevelopment began in almost all Latin American countries. The historical subject of liberation would be the oppressed people who should articulate practices that intended and point to a less dependent and unjust alternative society (BOFF, 1984, p. 24). Also according to Boff (2011), the poor, here, are not those who have needs; they have them, but they also have historical strength, capacity for change. This is not a Church for the poor, but a Church of the poor and for the poor (BOFF, 1984). The Brazilian Church realized that there is not only the modern world with its development, but a true world with its underdevelopment and this underdevelopment represents suffering for millions of people.

The Church’s involvement with the social issue had been organized in much of the Catholic world, even within the church’s social doctrine, but in 1968, during the Conference of the Latin American Episcopate in Medellin, this involvement became more systematized with a guideline: the preferential option for the poor. Although it is less known, it is the fact that Liberation Theology is not a theological movement that belonged to and belongs only to the Roman Catholic Church. Such a theological movement has crossed the denominational barrier and made and is part of the Protestant world in the same way. If on the one hand the Catholic Church organized and produced documents as quoted (Medellin), on the other side also the historical Protestants organized themselves within their ecclesial and ecclesiastical structures. According to Joanildo Burity,

the Conference had 167 participants representing 14 different Protestant denominations (including Baptists, congregational, Presbyterian, Episcopalians, Lutherans, Pentecostals, reformed, free Methodists) and delegates from five churches in the United States, Mexico and Uruguay as observers. Seventeen states of the country, including Pernambuco, were represented. It was, in 1964, the largest and most significant of the Promotions of the SRSI – Industry Social Service, and also the last, since, in 1964, after the military coup, the department was extinguished by CEB – Energy Company of Brasília (BURITY, 2011, p. 172).

Luiz Ernesto Guimarães, in his article entitled: “A Teologia da Libertação sob o Viés Protestante” wrote:

Thus, the Northeast Conference, together with other events formulated by Latin American Protestantism, supported and fostered the development of Christian social thought (CAVALCANTI, 2012). However, Liberation Theology was not the only result of this process that occurred in the progressive sectors. Other movements, currents and organizations were also being developed. As an example, we have: Latin American Theological Fraternity (FTL), University Bible Alliance (ABU), World Vision etc (GUIMARÃES, 2012, p. 940).

Names such as Rubem Alves, Paulo Stuart Wright, brother of the Reverend Jaime Wright, belong to subjects who had a remarkable performance in the years of military dictatorship and can not fail to be mentioned when discussing this period. Like an ecumenical work in the line of Liberation Theology, which proves that such theology did not belong only to the Catholic Church, it was the work developed in partnership between the then Cardinal Paul Evaristo Arns with the Reverend James Wright, in the years of the military dictatorship.

3. THEORETICAL AND THEOLOGICAL ASSUMPTIONS OF LIBERATION THEOLOGY

Boff (1980) adds, in Theology of Captivity and Liberation, that Christianity is a praxis of liberation. Liberation is a political concept (BOFF, 1980, p. 3). He considers human liberation as an anticipation of ultimate salvation. This is what is called in theology of the already and not yet, that is, the liberation of the unjust structures and death must happen, for the Liberating Christ is present through his Holy Spirit in the struggle of his people, with a view to encouraging the fight against discouragement, thus maintaining on the path towards promised liberation. On the other hand, it is not yet, for traditional Christian theology also believes that the last deliverance will take place only at the end of time, in which we will be all in all and have one shepherd for the whole flock (2 Cor 5:10).

However, one must be careful with this interpretation of traditional theology of liberation only in the future. And here is a very important reading key for liberation theologians: the anticipation of liberation. It is not only the subject of heaven, it is also the subject of the earth. Conforming to suffering on earth only after enjoying heaven, is definitely not a look of liberation theology. For this reason, one must think about the concepts of the already and the not yet mentioned. According to Renold Blank:

The first who radically formulated this commitment of eschatology to today’s historical reality was the Protestant theologian Jüngen Moltmann. In his work Theology of Hope, published in 1968, translated to the Portuguese in 1971, we can read the following programmatic observation: “Christian eschatology does not speak of the future. It has its starting point in a certain historical reality and predicts the future of this…” With this approach, Bultmann’s existential approach is overcome. It also goes beyond the fixation on the “last things” that marks both neo-classical eschatology. Instead, interest returns to the ancient eschatology of prophets. Return to that hopeful conception, as God leads this world throughout its historical process, towards a final goal. The theology of hope places eschatological discourse again on a historical and concrete basis. It overcomes the temptations of a dualist discourse, influenced by Gnostic conceptions. With this step, eschatology returns from its marginal position, which it had had within the theological discourse, to a central place (BLANK, 2000, p. 113-114).

Thus, with regard to the oppressive system, liberation theology, precisely because it believes that we must free ourselves, has its belief motivated in the God of the Covenant, presenting reflections from the Old Testament (OT) who led his people to the Promised Land (Exodus 33, 3), believing that we must work to change this world so that it is a better place for all to live. It is she who raises a strong moral and social criticism of dependent capitalism, based on the reflections of Fuerbach and Marx, who, in turn, denounce the alienating role of religion. Marx’s position on religion is known, for for he is the opium of the people.” However, one may question: would religion be opium or the salvation of oppressed people? Well, this is not the discussion of this article, but it remains the provocation.

Although Liberation Theology rejected many of the Marxist precepts, including the aforementioned phrase, it accepted, however, marxist methodology as a method of reading social and historical reality. It should be added that the method of Liberation Theology is the dialectical method expressed in SEE-JUDGE-ACT. From the point of view of theological assumptions, the starting point of Liberation Theology is anthropocentrism, because the poor is the center of thematic articulation of Christology and ecclesiology, according to Boff and Boff in “A Brief History of Liberation Theology” (BOFF; BOFF, 1980, p. 26). Still according to them, God cannot be a theological abstraction, for the Living and True God is active in history.

Blank (2000), in the same line of reasoning, argues that this God of life, finally, takes very sharp advantage in favor of all those whose life is threatened. He self-guardianship “go’él”, the defender of those who have no defender. The defender of the poor, the weak, the marginalized, the excluded (Ex 3.7; 21.25-27; 22.20; 22.25; 23.6; 23.10; Lv 25.25). Liberation Theology is not limited to theoretical deductions and does not be imprisoned to the academic model of theological articulation. Moreover, in Liberation Theology the fundamental issue is not Theology, but Liberation. It is understood liberation concretely, with the aim of ending the system of injustice expressed in capitalism, is to free oneanother from it to create in its place a new society (BOFF; BOFF, 1980, p. 70). And Moltmann says:

It is expected that “the man of our time again will become the receptacle of the influence of transcendental forces.” It is looking for “islands of meaning” in a world that, although not meaningless, is certainly non-human (MOLTMANN, 1971, p. 372).

Liberation Theology is a complex phenomenon. It aims to give a new global interpretation to Christianity. And to achieve this goal, it adopts a method to analyze and interpret reality. Method expressed in the acronym SEE-JUDGE-ACT and CELEBRATE. SEE reality from the rawest and harshest reality possible. According to Boff (2000), VER arouses compassion which, in turn, leads to the sacred wrath that impels the will to do something to overcome the situation.

Gutierres (1985) justifies this proposition of Liberation Theology based on the Theological concept that God is a liberating God and is revealed only in the concrete historical concept of the liberation of the poor and oppressed (GUTIERREZ, 1985). In suma, according to Boff and Boff (1980), liberation theology is conceived as a new hermeneutic of the Christian faith, as a new way of understanding the realization of Christianity in its entirety (BOFF; BOFF, 1980).

For Moltmann (1971, p. 405): “In this theology, the Christian faith becomes transcendent in the face of any socially experienceable context. It is not demonstrable – in its indemonstrability is precisely its strength, it is said – and therefore it is not rebuttable either.” Thus, it is worth assessing that disbelief, still according to the author, is the true enemy of the human being, and should also not be put as: “institutionalizable as a continuous reflection, being itself transcendence before social institutions” (MOLTMANN, 1971, p. 405). Faith is thus responsible for human transcendence.

4. DECADENCE AND FUTURE OF LIBERATION THEOLOGY

Who better and with more authority can talk about decay and the future of Liberation Theology is one of the most representative leaders of Liberation Theology in Brazil and Latin America: Leonardo Boff. In his work “Quarenta anos da Teologia da Libertação”, with deep regret, on the one hand, and with justified hope of continuity, on the other, Boff reflects on the cooling of the Catholic Church’s mood with social issues. It lists some of the causes such as the fall of Marxism in Europe and dictatorships in Latin America that have given life to the profound changes in the structure of the Churches. The momentum of opposition to authoritarian power has cooled. This impulse to renew the meaning and traditional religious practices led to the proposal to oppose the Church hierarchy to the nascent Church – People of God and the Church was opposed to Power to the Communion Church.

The issue of the poor and poverty, both in the church and in political society, has returned to what it was before: welfare. The poor reduced to the object of assistance and charity. It goes back to the conception of the poor as one who does not have and therefore he is not. Contrary to the conception of Liberation Theology, in which the poor is the one who has the strength of work, learning capacity and ability to reorganize and fight for their rights and enter the labor market, provided they offer them opportunities to learn. Therefore, the poor have historical strength to change the system of domination. A different poor person who not only wants to receive, but who thinks, speaks, organizes, that helps to build a new model of church – network – of communities is emphasized by theory.

Christian hope, by ochering to those orientations in the history of humanity, cannot harden itself in the past and the given present, and thus ally itself with the utopia of the status quo. It is called and empowered for the creative transformation of reality, because it has a perspective that refers to all reality. All things considered, the hope of faith can become an inexhaustible source for the creative and inventor imagination of love. It perennially provokes and produces anticipatory ideals of love for man and earth, while modeling the new emerging possibilities in the light of the promised future, and seeking, as far as possible, to create the best possible world, because what is promised is total possibility. It, therefore, always awakens the “passion of the possible”, the inventive gifts, the elasticity in transformations, the eruption of novelty after the old, the engagement of the new. Christian hope, in this sense, has always been revolutionaryally active in the course of the history of ideas in societies that were impregnated by it (MOLTMANN, 1971, p. 25).

However, this did not last long. From the 1970s on, the Vatican began to act in a way that “softens,” says Boff (1984), the postures of the most socially engaged religious. The justification for this smoothing was the persecution that the religious suffered by the military, as well as the cases of torture and violence that marked the period in which the Brazilian state was in the hands of the military. Also according to Boff (1984), with the end of the military regime, according to the conservative stance of the Vatican, all this smoothing was no longer justified. Add to this to the Vatican’s attitude that, in order to dampen the spirits of the defenders of the church’s intervention in the social issue, appointed conservative bishops not committed to the social issue in the main dioceses.

One of the enemies of Liberation Theology, no doubt, was Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, for he, liberation theology does not fit in the theological schemes of sane and classical Catholic theology. There is no way to accept a theology centered on earthly realities, ignoring the foundations of centuries of Catholic theology. It would be a contradiction to accept a theology centered on the poor and on the periphery of the church and the world. As president of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, many theologians were placed under surveillance, warned, marginalized in their communities, cornered, forbidden to exercise the ministry of the Word, removed from their chairs or subjected to doctrinal processes with the so-called “obsequious silence,” as Boff (2011) reports.

Ratzinger’s work also prohibited more than 100 theologians from across the continent from drawing up a collection of more than 537 tomes of Liberation Theology as a subsidy to students and pastoral agents who worked from the perspective of the poor. Liberation theology scholars are asking themselves today: what future does Liberation Theology have? Especially within the kind of Church institution that we have it centers on hierarchy as sacred power. Boff (2011), alludes to that it can only be a theology of captivity and revealed to marginality. By opting for power, the Church-institution has chosen those who also have power, in a word, the rich. The poor have lost their centrality. They are reserved for assistance and charity. Just as the theologians of liberation within the Catholic Church were silenced, this phenomenon also occurred among Protestants.

The period of the production of his thesis and publication – 1969 – is important to think about the emphasis that Rubem Alves places on politics. After all, not only Brazil, but many Latin American countries lived in great political and social effervescence, caused by the seizure of power by dictatorial governments. The suppression of democratic movements and the tolhimento of freedom of expression provoked, on the continent, a wave of terror and fear; those who opposed such government leaders were completely vulnerable, without any rights guaranteed, even at the risk of dying – or “disappearing” (GUIMARÃES, 2012, p. 941).

But all is not lost. Although it does not present itself as “Liberation Theology”, their roots remain present and producing results. It is not explicitly found in the faculties and institutes of theology. She lives on the bases, in bible reading, in biblical circles, in the basic ecclesial communities, in pastoral, in faith and political movements, and in pastoral work in the periphery, according to Boff (2011). Liberation Theology has a future that is reserved for the poor and oppressed.

FINAL CONSIDERATIONS

We believe that we have achieved the objective proposed in the introduction, that of presenting, succinctly, the panorama of Liberation Theology in the context of Latin America, where this movement has been most over. As said and reaffirmed, this article was supposed to be only a provocation to the deepening of the theme so dear to us and to so many, given its complexity, that is, it is only a launch ing the seed with the hope that it will fall into good ground and then produce good fruit. As mentioned, such a theological movement was not only a monopoly of the Roman Catholic Church, but also several Protestant Churches became involved with their exponents, some of them better known and mentioned in the course of the article.

This fact is a cause for joy for us, after all the Gospel is of all denominations and of all those who take it as a manual of faith and conduct of life. Another common point that deserves to be highlighted in these final considerations is that just as Catholic theologians and liberation theologians were silenced over time by their modus procedendi, likewise, protestant theologians and theologians were silenced, whether clerics or lay people. This fact, despite being a bad sign, is, at the same time, a good sign, after all the prophetic voice has always bothered and will continue bothering and this is definitely a good sign. To think about such issues is to reflect on the modern world, which justifies the relevance of the proposal.

REFERENCES

ALTMANN, W. Teologia da libertação. Estudos Teológicos, v. 19, n. 1, p. 27-35, 1979.

BEZERRA, E. A.; DELGADO, L. de. A. N.; OLIVEIRA, V. C. J. de. Do humanismo cristão à práxis política de oposição a ditadura: memória de uma experiência dominicana”. Disponível em: www.fiocruz.br/ehosudeste/cgi/cgilua.exe/sys/start.htm?siol=16. Acesso em: 01 out. 2014.

BLANK, R. Escatologia da pessoa: vida, morte e ressurreição. (Escatologia I). São Paulo: Paulus, 2000.

BLANK, R. Escatologia do mundo: o projeto cósmico de Deus. (Escatologia II). São Paulo: Paulus, 2001.

BOFF, L. Quarenta anos da teologia da libertação. Petrópolis: Vozes, 2011.

________, L. Igreja: Carisma e poder. São Paulo: Ática, 1994.

________, L. Jesus Cristo Libertador. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1975.

________, L. Teologia do Cativeiro e da Libertação. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1980.

________,L. Saber Cuidar. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1999.

BOFF, L.; REGIDOR, J. R.; BOFF, C. A teologia da Libertação: balanços e perspectivas. São Paulo: Ática, 1996.

CATÃO, F. A. C. O que é Teologia da Libertação. São Paulo: Brasiliense, 1986.

DELGADO, L. de. A. N.; PASSOS, M. “Catolicismo: direitos sociais e direitos humanos (1960-1970)”. In: FERREIRA, J.; DELGADO, L. de. A. N. (orgs.). O Brasil Republicano. Volume 4: O tempo da ditadura: Regime militar e movimentos sociais em fins do século XX. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira, 2003.

GUIMARÃES, L. E. A Teologia da Libertação sob o viés protestante. In: IX SEPECH, p. 933-947, 2012.

GUTIERREZ, G. Teologia da Libertação. Petrópolis: Vozes,1985.

LOVATO, F. F. de A. A Teologia da Libertação na América Latina e suas manifestações em Santa Maria- RS. In: QUEVEDO, J.; IOKOI, Z. M. G. (orgs.). Movimentos Sociais na América Latina: desafios teóricos em tempos de globalização. Santa Maria: MILA-CCSH, 2007.

MOLTMANN, J. Teologia da esperança: estudos sobre os fundamentos e as consequências de uma escatologia cristã. São Paulo: Herder, 1971

MONDIN, B. Os teólogos da libertação. São Paulo: Paulinas, 1980.

REGAN, D. Igreja para a Libertação: Retrato pastoral da Igreja no Brasil. São Paulo: Paulinas, 1986.

ROUQUIÉ, A. Igreja e Igrejas. In: O extremo-ocidente: introdução à América Latina. São Paulo: EDUSP, 1991.

SCHMITT, C. O Conceito de Político. Petrópolis: Vozes, 1992.

SOBRINO, J. Jesus, o Libertador. São Paulo: Vozes, 1994.

APPENDIX – FOOTNOTE REFERENCES

3. When we talk about Christ Pantocrator, one soon thinks of the iconographic figure (Byzantine tradition) of Christ emperor of the cosmos. It is in Orthodox theology that such a cultica and iconographic emphasis is found, or even in churches of Eastern tradition, such as the Melchite Church, for example, being this part of the Roman Catholic Church. And here when we speak of Orthodox theology, a reference is made to the Orthodox Liturgy, to the Mass itself, for it is in this liturgy where all the greatness of worship and praise must be given to God through christ the Emperor of the cosmos is expressed. “This kind of image of Christ is given the generic name of “Pantocrator” so rich in meanings. The Greek term, generally translated as “Omnipotent”, but which is better translated by the expression “Omniregente”, or “He who rules everything”, is a term that is already found in pagan literature. It is found in the Greek version of the Seventy that takes it up to translate the expression “Sabaoth”, giving it the meaning of God “Dominating of all earthly and heavenly powers. Available in: https://www.ecclesia.com.br/biblioteca/iconografia/o_tipo_iconografico_do_pantokrator.html. Access on 01 Mar. 2020.

4. One of the leading Latin American theologians and one of the exponents of Liberation Theology, Gustavo Gutiérrez joined the National Major University of São Marcos (UNMSM) in 1947, where he studied four years of medicine. At the same time, he took the Course of Letters at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru. In these years he participated, as a laic, in Catholic Action. From 1951 to 1955, he studied philosophy and psychology at the Catholic University of Louvain (Belgium) and graduated in psychology. From 1955 to 1959, he studied theology at the Catholic University of Lyon (France) – where he obtained his doctorate in theology in 1985 – and from 1959 to 1960 at the Gregorian University in Rome. Between 1962 and 1963, he studied at the Institut Catholique in Paris. Gutiérrez was ordained a priest in 1959. The following year, on his return to Peru, he took over the advice of the National Union of Catholic Students (UNEC), which would later give rise to the Catholic Professionals Movement, both linked to the international Catholic movement of Pax Romana students and intellectuals. Also in 1960, he began teaching at the Pontifical Catholic University, of whose Department of Theology was principal professor. His courses at the Faculty of Letters and then in Social Sciences were a dialogue between the Christian faith and contemporary thought. In the early 1960s, he attended the Second Vatican Council as theological advisor to Monsignor Manuel Larraín of Chile. Later, he participated in the preparations of the various Departments of the Latin American Episcopal Council (CELAM), of the II General Conference of the Latin American Episcopate, in Medellín (Colombia), in 1968, to which he attended as a theological expert. From 1967 to 1979, he was a member of celam’s Theological Reflection Team and, from 1968 to 1980, he was part of the Theological Reflection Team of the Peruvian Episcopal Conference. In 1979, he was also advisor to several Latin American bishops at the Second General Conference of the Latin American Episcopate in Puebla (Mexico).

[1] PhD student in Education at the University Of Piracicaba (UNIMEP). Master in Education from the Metodist University of Piracicaba (UNIMEP) 2019; Lines of Research, History and Philosophy of Education. Graduated in History from UNIESP 2012. Bachelor’s degree in Philosophy from the Claretian University Center 2014/2019 (CLARETIANO). Bachelor of Theology from the Claretian University Center (CLARETIANO) 2015. Graduated in Pedagogy from the University Center of Araras (UNAR) 2016. Graduated in Sociology from the University Center of Araras (UNAR) 2018. Graduated in Geography from the University Center of Araras (UNAR) 2020.

[2] Master’s degree in Education from Universidade Nove de Julho (UNINOVE), 2019; Research line: Education, Philosophy and Human Formation (LIPEFH), member of the Research and Study Group in Philosophy of Education – (GRUPEFE) and Research and Study Of Complexity Group (GRUPEC), under the coordination of Profs. Dr. Antônio Joaquim Severino and Dra. Cleide Rita Silvério de Almeida (UNINOVE). Lato Sensu Post-Graduation in Teacher Training for Higher Education by the University Center Asunción (UNIFAI) 2015; Postgraduate in Reformed Theology by the Evangelical Literary Mission (CFL) 2019; Bachelor’s degree in Theology from the Pontifical Faculty of Theology Of Our Lady of the Assumption – Assumption University Center (UNIFAI) 2007; Bachelor’s degree in Theology from the Anglican Institute of Theological Studies (IAET) 2005.

Sent: March, 2020.

Approved: May, 2020.